Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Target ship

View on Wikipedia

A target ship is a vessel — typically an obsolete or captured warship — used as a seaborne target for naval gunnery practice or for weapons testing. Targets may be used with the intention of testing effectiveness of specific types of ammunition; or the target ship may be used for an extended period of routine target practice with specialized non-explosive ammunition. The potential consequences of a drifting wreck require careful preparation of the target ship to prevent pollution, or a floating or submerged collision risk for maritime navigation.

Rationale

[edit]

Sinking redundant warships is an effective way of testing new weapons and warships in as realistic a manner as possible.

Preparation

[edit]In order to meet environmental, health, and safety standards, ships now have to be thoroughly cleaned so that all dangerous material and potential contaminants (such as asbestos, refrigerants etc.) are removed. In the event of the vessel becoming an artificial reef, escape exits also have to be created in it, should divers encounter problems.

Notable examples

[edit]- Pacificateur

In September 1819, the French engineer and Army artillery officer Henri-Joseph Paixhans wrote to the Ministry of the Navy to propose a fusing system to fire explosive shells at wooden warships, instead of the usual, solid round shots that were then in general naval use.[Notes 1][1][2] A commission studied the matter, and decided to build two Paixhans howitzers for trial purposes in 1822.

In 1824, the 80-gun ship of the line Pacificateur, made redundant by the Bourbon Restoration, was condemned. She was a Bucentaure-class two-decker of the same type as the French flagship of the Battle of Trafalgar. The two prototypes were fired at her with devastating effect. This led to the adoption of the Paixhans gun in 1827. They were used to great effect at the Battle of San Juan de Ulua, to the interest of British and US observers, who announced the demise of wooden warships and the era of the ironclad.[citation needed]

- Baden

In 1921 former German battleship SMS Baden was used by the Royal Navy to test new types of shells. The tests indicated that medium-strength armour could not stop the latest armour-piercing shells, causing the British switch to an all or nothing armour scheme for their new battleships. Baden was then scuttled in Hurd Deep.[3]

- Agamemnon and Centurion

The British pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Agamemnon was converted to radio-control in 1920–1921 and used for assessments of the damage that could be caused by aircraft and various calibres of guns. She was replaced in the role by the battleship Centurion in 1926. This followed the work by the secret Distantly Controlled Boat (DCB) Section of the Royal Navy's Signals School, Portsmouth started in 1917.[4]

- Iowa (BB-4)

After World War I ended, the US Navy and Army did live fire testing of attacking warships from the air. To get the testing as close to wartime conditions as possible, a well known radio engineer, John Hays Hammond Jr., developed the radio control gear to convert USS Iowa (BB-4) into a remote-controlled target ship, a US naval first. She was sunk off the Pacific coast of Panama during fleet exercises by the battleship Mississippi, with members of the United States Congress and the press attending.[5] In the early 1930s the US Navy put considerable effort into the development of remote control ships and fitted the destroyer Stoddert with improved radio controls developed by Lieutenant Commander Boyd R. Alexander, a radio design officer, and the Naval Research Laboratory in Bellevue DC for further testing and evaluation. The evaluation proved so successful that the US Navy moved up their plans for radio controlled warships and in 1932 the obsolete battleship USS Utah and the destroyers Boggs and Kilty were converted.[6]

- James Longstreet

A familiar sight for more than fifty years in Cape Cod Bay, Massachusetts, was SS James Longstreet. This World War II Liberty ship was towed to a sandbar 3.5 miles (5.6 km) off shore in 1944 and was used for bombing practice through the Vietnam War.

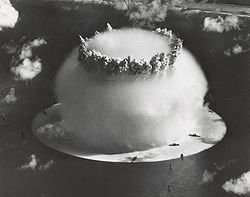

- Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a 1946 series of US nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll that used 95 target ships. Some were obsolete US ships, such as USS Nevada, others were ships surrendered by the Axis powers at the end of World War II, such as the German heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen and the Japanese battleship Nagato.

- Torrens

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) sank HMAS Torrens on June 14, 1999 with a Mk48 wire guided torpedo fired from the Collins-class submarine HMAS Farncomb. Torrens was the last of six Australian River-class destroyer escorts, the others (Derwent, Parramatta, Stuart, Swan and Yarra) having been disposed of previously. Before the sinking Torrens had been thoroughly cleaned of all fuels, oils and potentially environmentally harmful substances. Her gun turret was donated to the South Western City of Albany. Torrens was then towed from Fleet Base West (HMAS Stirling) 90 kilometres (56 mi) out to sea, west of Perth. The submarine fired the torpedo at the stationary target from a submerged position over the horizon.

The sinking of Torrens was a display of firepower that provided some much needed positive publicity for the Collins-class submarines, plagued by numerous technical problems and criticised over troubles with the combat system and noise reduction. Ric Shalders, commander of the Submarine Squadron said "the requirement of new submarine trials, the new need to test war-stock and the availability of the Torrens all came together to produce a very satisfactory result".[7]

As exercises

[edit]

The US military term Sink Exercise (SINKEX) is used for the test of a weapons system usually involving a torpedo or missile attack of an unmanned target ship. The US Navy uses SINKEXs to train its sailors on the use of weapons.[8]

This technique is used to dispose of decommissioned warships.[9] The US Navy performs SINKEXs north of Kauaʻi, Hawaii; in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California; and near Puerto Rico.[9]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Artillery Jeff Kinard, Spencer C. (INT) Tucker p.235-236

- ^ Neptunia 262, p. 49

- ^ Schleihauf, William (2007). The Baden Trials. US Naval Institute Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-1844860418.

- ^ UK National Archives ADM 1/8539/253 Capabilities of distantly controlled boats. Reports of trials at Dover 28 - 31 May 1918

- ^ "Coast Battleship No. 4 (ex-USS Iowa, Battleship # 4) – As a Target Ship, 1921–1923". Department of the Navy—Naval Historical Center. 2009-09-08. Archived from the original on 2010-02-09. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ "U.S. Navy Gets Crewless Ghost Fleet" Popular Science, February 1932

- ^ Jeremy Olver (8 April 2001). "The Royal Navy Postwar: Type 12 Sinkings". www.btinternet.com. Archived from the original on 2006-12-12. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ^ Pike, John (2005-09-01). "SINKEX - Sinking Exercise". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- ^ a b Doehring, Thoralf (2008). "US Navy Ship Sinking Exercises (SINKEX)". Retrieved 2009-02-21.

External links

[edit]- "Robot Warships" Popular Mechanics, July 1934, pp. 72–75 conversion of the Boggs to a radio controlled target ship

.jpg/250px-Targetship_ex-USS_Connolly_(DD-979).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Targetship_ex-USS_Connolly_(DD-979).jpg)