Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Operation Crossroads

View on Wikipedia

| Operation Crossroads | |

|---|---|

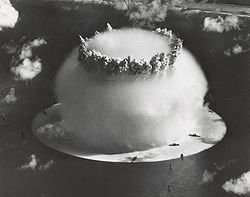

Operation Crossroads test detonations of Able (top) and Baker (bottom). | |

| |

| Information | |

| Country | United States |

| Test site | NE Lagoon, Bikini Atoll |

| Period | 1946 |

| Number of tests | Two tested and one cancelled. |

| Test type | Free fall air drop, Underwater |

| Max. yield | 22–23 kilotonnes of TNT (92–96 TJ) |

| Test series chronology | |

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity on July 16, 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the atomic bombing of Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. The purpose of the tests was to investigate the effect of nuclear weapons on warships.

The Crossroads tests were the first of many nuclear tests held in the Marshall Islands and the first to be publicly announced beforehand and observed by an invited audience, including a large press corps. They were conducted by Joint Army/Navy Task Force One, headed by Vice Admiral William H. P. Blandy rather than by the Manhattan Project, which had developed nuclear weapons during World War II. A fleet of 95 target ships was assembled in Bikini Lagoon and hit with two detonations of Fat Man plutonium implosion-type nuclear weapons of the kind dropped on Nagasaki in 1945, each with a yield of 23 kilotons of TNT (96 TJ).

The first test was Able. The bomb was named Gilda after Rita Hayworth's character in the 1946 film Gilda and was dropped from the B-29 Superfortress Dave's Dream of the 509th Bombardment Group on July 1, 1946. It detonated 520 feet (158 m) above the target fleet and caused less than the expected amount of ship damage because it missed its aim point by 2,130 feet (649 m).

The second test was Baker. The bomb was known as Helen of Bikini and was detonated 90 feet (27 m) underwater on July 25, 1946. Radioactive sea spray caused extensive contamination. A third deep-water test named Charlie was planned for 1947 but was canceled primarily because of the United States Navy's inability to decontaminate the target ships after the Baker test. Ultimately, only nine target ships were able to be scrapped rather than scuttled. Charlie was rescheduled as Operation Wigwam, a deep-water shot conducted in 1955 off the coast of Mexico (Baja California).

Bikini's native residents were evacuated from the island on board the LST-861, with most moving to the Rongerik Atoll. In the 1950s, a series of large thermonuclear tests rendered Bikini unfit for subsistence farming and fishing because of radioactive contamination. Bikini remains uninhabited as of 2017[update], though it is occasionally visited by sport divers.

Planners attempted to protect participants in the Operation Crossroads tests against radiation sickness, but one study showed that the life expectancy of participants was reduced by an average of three months. The Baker test's radioactive contamination of all the target ships was the first case of immediate, concentrated radioactive fallout from a nuclear explosion. Chemist Glenn T. Seaborg, the longest-serving chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, called Baker "the world's first nuclear disaster."[1]

Background

[edit]The first proposal to test nuclear weapons against naval warships was made on August 16, 1945, by Lewis Strauss, future chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission. In an internal memo to Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, Strauss argued, "If such a test is not made, there will be loose talk to the effect that the fleet is obsolete in the face of this new weapon and this will militate against appropriations to preserve a postwar Navy of the size now planned."[2] With very few bombs available, he suggested a large number of targets widely dispersed over a large area. A quarter century earlier, in 1921, the Navy had suffered a public relations disaster when General Billy Mitchell's bombers sank every target ship the Navy provided for the Project B ship-versus-bomb tests.[3] The Strauss test would be designed to demonstrate ship survivability.[4]

In August 1945, Senator Brien McMahon, who within a year would write the Atomic Energy Act and organize and chair the Congressional Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, made the first public proposal for such a test, but one designed to demonstrate the vulnerability rather than survivability of ships. He proposed dropping an atomic bomb on captured Japanese ships and suggested, "The resulting explosion should prove to us just how effective the atomic bomb is when used against the giant naval ships."[5] On September 19, the Chief of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), General of the Army Henry H. Arnold, asked the Navy to set aside 10 of the 38 captured Japanese ships for use in the test proposed by McMahon.[6]

Meanwhile, the Navy proceeded with its own plan, which was revealed at a press conference on October 27 by the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, Fleet Admiral Ernest King. It involved between 80 and 100 target ships, most of them surplus U.S. ships.[6] As the Army and the Navy maneuvered for control of the tests, Assistant Secretary of War Howard C. Peterson observed, "To the public, the test looms as one in which the future of the Navy is at stake ... if the Navy withstands [the tests] better than the public imagines it will, in the public mind the Navy will have 'won.'"[7]

The Army's candidate to direct the tests, Major General Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project which built the bombs, did not get the job. The Joint Chiefs of Staff decided that because the Navy was contributing the most men and materiel, the test should be headed by a naval officer. Commodore William S. "Deak" Parsons was a naval officer who had worked on the Manhattan Project and participated in the bombing of Hiroshima.[8] He had been promoted to assistant to the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Special Weapons, Vice Admiral William H. P. Blandy,[9] whom Parsons proposed for the role. This recommendation was accepted, and on January 11, 1946, President Harry S. Truman appointed Blandy as head of Army/Navy Joint Task Force One (JTF-1), which was created to conduct the tests. Parsons became Deputy Task Force Commander for Technical Direction. USAAF Major General William E. Kepner was Deputy Task Force Commander for Aviation. Blandy codenamed the tests Operation Crossroads.[10][11]

Under pressure from the Army, Blandy agreed to crowd more ships into the immediate target area than the Navy wanted, but he refused USAAF Major General Curtis LeMay's demand that "every ship must have a full loading of oil, ammunition, and fuel."[12] Blandy's argument was that fires and internal explosions might sink ships that would otherwise remain afloat and be available for damage evaluation. When Blandy proposed an all-Navy board to evaluate the results, Senator McMahon complained to Truman that the Navy should not be "solely responsible for conducting operations which might well indeed determine its very existence."[13] Truman acknowledged that "reports were getting around that these tests were not going to be entirely on the level." He imposed a civilian review panel on Operation Crossroads to "convince the public it was objective."[14]

Opposition

[edit]Pressure to cancel Operation Crossroads altogether came from scientists and diplomats. Manhattan Project scientists argued that further testing was unnecessary and environmentally dangerous. A Los Alamos study warned "the water near a recent surface explosion will be a witch's brew" of radioactivity.[15] When the scientists pointed out that the tests might demonstrate ship survivability while ignoring the effect of radiation on sailors,[16] Blandy responded by adding test animals to some of the ships, thereby generating protests from animal rights advocates.[17] J. Robert Oppenheimer declined an invitation to attend the test and wrote to President Truman about his objections to it, arguing that any data obtained from the test could be obtained more accurately and cheaply in a laboratory.[18]

Secretary of State James F. Byrnes, who a year earlier had told physicist Leo Szilard that a public demonstration of the bomb might make the Soviet Union "more manageable" in Europe,[19] now argued the opposite: that further display of U.S. nuclear power could harden the Soviet Union's position against acceptance of the Acheson–Lilienthal Plan, which discussed possible methods for the international control of nuclear weapons and the avoidance of future nuclear warfare. At a March 22 cabinet meeting he said, "from the standpoint of international relations it would be very helpful if the test could be postponed or never held at all."[20] He prevailed on Truman to postpone the first test for six weeks, from May 15 to July 1. For public consumption, the postponement was explained as an opportunity for more Congressional observers to attend during their summer recess.[21]

When Congressmen complained about the destruction of $450 million worth of target ships, Blandy replied that their true cost was their scrap value at $10 per ton, only $3.7 million.[22] Veterans and legislators from New York and Pennsylvania requested to keep their namesake battleships as museum ships, as Texas had done with USS Texas, but the JTF-1 replied that "it is regretted that such ships as the USS New York cannot be spared."[23]

Preparation

[edit]

A series of three tests was recommended to study the effects of nuclear weapons on ships, equipment, and materiel. The test site had to be in territory controlled by the United States. The inhabitants would have to be evacuated, so it was best if it was uninhabited, or nearly so, and at least 300 miles (500 km) from the nearest city. So that a B-29 Superfortress could drop a bomb, there had to be an airbase within 1,000 miles (1,600 km). To contain the target ships, it needed to have a protected anchorage at least 6 miles (10 km) wide. Ideally, it would have predictable weather patterns and be free of severe cold and violent storms. Predictable winds would avoid having radioactive material blown back on the task force personnel, and predictable ocean currents would allow material to be kept away from shipping lanes, fishing areas, and inhabited shores.[24] Timing was critical because Navy manpower required to move the ships was being released from active duty as part of the post-World War II demobilization, and civilian scientists knowledgeable about atomic weapons were leaving federal employment for college teaching positions.[25]

On January 24, Blandy named the Bikini Lagoon as the site for the two 1946 detonations, Able and Baker. The deep underwater test, Charlie, scheduled for early 1947, would take place in the ocean west of Bikini.[26] Of the possible places given serious consideration, including Ecuador's Galápagos Islands,[27] Bikini offered the most remote location with a large protected anchorage, suitable but not ideal weather,[28] and a small, easily moved population. It had come under exclusive United States control on January 15, when Truman declared the United States to be the sole trustee of all the Pacific islands captured from Japan during the war. The Navy had been studying test sites since October 1945 and was ready to announce its choice of Bikini soon after Truman's declaration.[29] On February 6, the survey ship Sumner began blasting channels through the Bikini reef into the lagoon. The local residents were not told why.[30]

The 167 Bikini islanders first learned their fate four days later, on Sunday, February 10, when Navy Commodore Ben H. Wyatt, United States military governor of the Marshall Islands, arrived by seaplane from Kwajalein. Referring to Biblical stories which they had learned from Protestant missionaries, he compared them to "the children of Israel whom the Lord saved from their enemy and led into the Promised Land." He also claimed it was "for the good of mankind and to end all world wars." There was no signed agreement, but he reported by cable "their local chieftain, referred to as King Juda, arose and said that the natives of Bikini were very proud to be part of this wonderful undertaking."[31] On March 6, Wyatt attempted to stage a filmed reenactment of the February 10 meeting in which the Bikinians had given away their atoll. Despite repeated promptings and at least seven retakes, Juda confined his on-camera remarks to, "We are willing to go. Everything is in God's hands." The next day, LST-861 moved them and their belongings 128 miles (206 km) east to the uninhabited Rongerik Atoll, to begin a permanent exile.[32] Three Bikini families returned in 1974 but were evacuated again in 1978 because of radioactivity in their bodies from four years of eating contaminated food.[33] As of 2022, the atoll remains unpopulated.[34]

Ships

[edit]

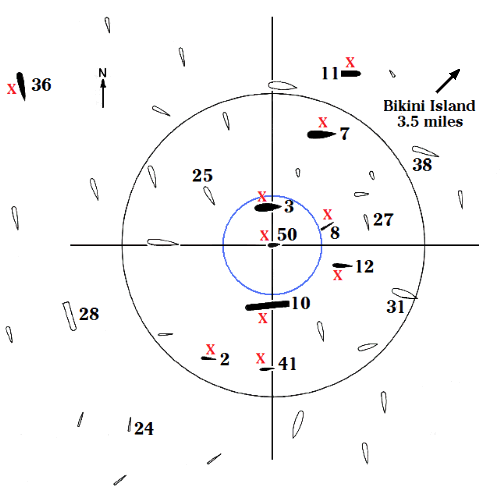

To make room for the target ships, 100 short tons (90 t) of dynamite were used to remove coral heads from Bikini Lagoon. On the grounds of the David Taylor Model Basin outside Washington, DC, dress rehearsals for Baker were conducted with dynamite and model ships in a pond named "Little Bikini."[35] A fleet of 93 target vessels was assembled in Bikini Lagoon. At the center of the target cluster, the density was 20 ships per square mile (7.7 per km2), three to five times greater than military doctrine would allow. The stated goal was not to duplicate a realistic anchorage but to measure damage as a function of distance from the blast center, at as many distances as possible.[36] The arrangement also reflected the outcome of the Army/Navy disagreement about how many ships should be allowed to sink.[37]

The target fleet included four obsolete U.S. battleships, two aircraft carriers, two cruisers, thirteen destroyers, eight submarines, forty landing ships, eighteen transports, two oilers, one floating drydock, and three surrendered Axis ships, the Japanese cruiser Sakawa, the battleship Nagato, and the German cruiser Prinz Eugen.[25] The ships carried sample amounts of fuel and ammunition, plus scientific instruments to measure air pressure, ship movement, and radiation. The live animals on some of the target ships[38] were supplied by the support ship USS Burleson, which brought 200 pigs, 60 guinea pigs, 204 goats, 5,000 rats, 200 mice, and grains containing insects to be studied for genetic effects by the National Cancer Institute.[25] Amphibious target ships were beached on Bikini Island.[39]

A support fleet of more than 150 ships provided quarters, experimental stations, and workshops for most of the 42,000 men (more than 37,000 of whom were Navy personnel) and the 37 female nurses.[40] Additional personnel were located on nearby atolls such as Eniwetok and Kwajalein. Navy personnel were allowed to extend their service obligation for one year if they wanted to participate in the tests and see an atomic bomb explode.[41] The islands of the Bikini Atoll were used as instrumentation sites and, until Baker contaminated them, as recreation sites.[42]

Cameras

[edit]

Radio-controlled autopilots were installed in eight B-17 bombers, converting them into remote-controlled drones which were then loaded with automatic cameras, radiation detectors, and air sample collectors. Their pilots operated them from mother planes at a safe distance from the detonations. The drones could fly into radiation environments, such as Able's mushroom cloud, which would have been lethal to crew members.[43] All the land-based detonation-sequence photographs were taken by remote control from tall towers erected on several islands of the atoll. In all, Bikini cameras took 50,000 still pictures and 1,500,000 feet (460,000 m) of motion picture film. One of the cameras could shoot 1,000 frames per second.[44]

Before the first test, all personnel were evacuated from the target fleet and Bikini Atoll. They boarded ships of the support fleet, which took safe positions at least 10 nautical miles (19 km) east of the atoll. Test personnel were issued special dark glasses to protect their eyes, but a decision was made shortly before Able that the glasses might not be adequate. Personnel were instructed to turn away from the blast, shut their eyes, and cradle their arm across their face for additional protection. A few observers who disregarded the recommended precautions advised the others when the bomb detonated. Most shipboard observers reported feeling a slight concussion and hearing a disappointing little "poom".[41]

On July 26, 2016, the National Security Archive declassified and released the entire stock of footage shot by surveillance aircraft that flew over the nuclear test site just minutes after the bomb detonated.[45][46] The footage can be seen on YouTube.[47]

Nicknames

[edit]Able and Baker are the first two letters of the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet, used from 1941 until 1956. Alfa and Bravo are their counterparts in the current NATO phonetic alphabet. Charlie is the third letter in both systems. According to eyewitness accounts, the time of detonation for each test was announced as H or How hour;[48] in the official JTF-1 history, the term M or Mike hour is used instead.[49]

There were only seven nuclear bombs in existence in July 1946.[50] The two bombs used in the test were Fat Man plutonium implosion-type nuclear weapons of the kind dropped on Nagasaki. The Able bomb was stenciled with the name Gilda and decorated with an Esquire magazine photograph of Rita Hayworth, star of the 1946 movie, Gilda.[51] The Baker bomb was Helen of Bikini. This femme-fatale theme for nuclear weapons, combining seduction and destruction, is epitomized by the use in all languages, starting in 1946, of "bikini" as the name for a woman's two-piece bathing suit.[52]

| Name | Date, time (UTC) | Location | Elevation + height | Delivery | Purpose | Device | Yield | Refer- ences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Able | June 30, 1946 21:00:01.0 | NE Lagoon, Bikini Atoll 11°35′N 165°30′E / 11.59°N 165.50°E | 0 + 158 m (518 ft) | Free fall air drop |

Weapon effect | Mk III "Gilda" | 23 kt | [53][54][55][56][57] |

| Baker | July 24, 1946 21:34:59.8 | NE Lagoon, Bikini Atoll 11°35′N 165°31′E / 11.59°N 165.52°E | 0 – 27.5 m (90 ft) | Under- water |

Weapon effect | Mk III "Helen of Bikini" | 23 kt | [53][54][57] |

| Charlie (canceled) |

March 1, 1947 | NE Lagoon, Bikini Atoll 11°34′N 165°31′E / 11.57°N 165.51°E | 0 – 50 m (160 ft) | Under- water |

Weapon effect | Mk III | 23 kt | [57] |

The United States' test series summary table is here: United States' nuclear testing series.

Test Able

[edit]

Detonation

[edit]

At 09:00 on July 1, 1946, Gilda was dropped from the B-29 Dave's Dream of the 509th Bombardment Group, piloted by Major Woodrow Swancutt under the command of Brigadier General Roger M. Ramey.[58] The plane, formerly known as Big Stink, had been the photographic equipment aircraft on the Nagasaki mission in 1945. It had been renamed in honor of Dave Semple, a bombardier who was killed during a practice mission on March 7, 1946.[59] Gilda detonated 520 feet (158 m) above the target fleet, with a yield of 23 kilotons. Five ships were sunk.[25][36] Two attack transports sank immediately, two destroyers within hours, and Sakawa the following day.[60]

Some of the 114 press observers expressed disappointment at the effect on ships.[61] The New York Times reported, prematurely, that "only two were sunk, one capsized, and eighteen damaged."[62] The next day, the Times carried an explanation by Forrestal that "heavily built and heavily armored ships are difficult to sink unless they sustain underwater damage."[63]

The main cause of less-than-expected ship damage was that the bomb missed its aim point by 710 yards (649 m).[64] The ship the bomb was aimed at failed to sink. The miss resulted in a government investigation of the flight crew of the B-29 bomber. Various explanations were offered, including the bomb's known poor ballistic characteristics, but none was convincing. Images of the drop were inconclusive. The bombsight was checked and found error free. Pumpkin bomb drops were conducted and were accurate. Colonel Paul W. Tibbets believed that the miss was caused by a miscalculation by the crew. The mystery was never solved.[65][66]

There were other factors that made Able less spectacular than expected. Observers were much farther away than at the Trinity test, and the high humidity absorbed much of the light and heat.[67]

The battleship USS Nevada, the only battleship to get underway at the Attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, had been designated as the aim point for Able and was painted orange, with white gun barrels and gunwales, to make her stand out in the central cluster of target ships. There were eight ships within 400 yards (366 m) of it. Had the bomb exploded over the Nevada as planned, at least nine ships, including two battleships and an aircraft carrier, likely would have sunk. The actual detonation point, west-northwest of the target, was closer to the attack transport USS Gilliam, in much less crowded water.[68]

Able Target array

[edit]

| # | Name | Type | Distance from zero |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Gilliam | Transport | 50 yd (46 m) |

| 9 | Sakawa | Cruiser | 420 yd (380 m) |

| 4 | Carlisle | Transport | 430 yd (390 m) |

| 1 | Anderson | Destroyer | 600 yd (550 m) |

| 6 | Lamson | Destroyer | 760 yd (690 m) |

| # | Name | Type | Distance from zero |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | Skate | Submarine | 400 yd (370 m) |

| 12 | YO-160 | Yard oiler | 520 yd (480 m) |

| 28 | Independence | Aircraft carrier | 560 yd (510 m) |

| 22 | Crittenden | Transport | 595 yd (544 m) |

| 32 | Nevada | Battleship | 615 yd (562 m) |

| 3 | Arkansas | Battleship | 620 yd (570 m) |

| 35 | Pensacola | Cruiser | 710 yd (650 m) |

| 11 | ARDC-13 | Drydock | 825 yd (754 m) |

| 23 | Dawson | Transport | 855 yd (782 m) |

| 38 | Salt Lake City | Cruiser | 895 yd (818 m) |

| 27 | Hughes | Destroyer | 920 yd (840 m) |

| 37 | Rhind | Destroyer | 1,012 yd (925 m) |

| 49 | LST-52 | LST | 1,530 yd (1,400 m) |

| 10 | Saratoga | Aircraft carrier | 2,265 yd (2,071 m) |

In addition to the five ships that sank, fourteen were judged to have serious damage or worse, mostly as a result of the shock wave. All but three were located within 1,000 yards (900 m) of the detonation. Inside that radius, orientation to the bomb was a factor in shock wave impact. For example, ship #6, the destroyer USS Lamson, which sank, was farther away than seven ships that stayed afloat. Lamson was broadside to the blast, taking the full impact on her port side, while the seven closer ships were anchored with their sterns toward the blast, somewhat protecting the most vulnerable part of the hull.[70]

The only large ship inside the 1000-yard radius which sustained moderate rather than serious damage was the sturdily built Japanese battleship Nagato, ship #7, whose stern-on orientation to the bomb gave her some protection. Unrepaired damage from World War II may have complicated damage analysis. As the ship from which the Pearl Harbor attack had been commanded, Nagato was positioned near the aim point to guarantee her being sunk. The Able bomb missed its target, and the symbolic sinking came three weeks later, five days after the Baker shot.[71]

Fire caused serious damage to ship #10, the aircraft carrier Saratoga, more than 1 mile (1.6 km) from the blast. For test purposes, all the ships carried sample amounts of fuel and ordnance, plus airplanes. Most warships carried a seaplane on deck which could be lowered into the water by crane,[72] but Saratoga carried several airplanes with highly volatile aviation fuel, both on deck and in the hangars below. The fire was extinguished, and Saratoga was kept afloat for use in the Baker shot.[73][74]

Radiation

[edit]

As with Little Boy (Hiroshima) and Fat Man (Nagasaki), the Crossroads Able shot was an air burst. These were purposely detonated high enough in the air to prevent surface materials from being drawn into the fireball. The height-of-burst for the Trinity test was 100 feet (30 m); the device was mounted on a tower. It made a crater 6 feet (1.8 m) deep and 500 feet (150 m) wide, and there was some local fallout. The test was conducted in secret, and the world at large learned nothing about the radioactive fallout at the time.[75] To be a true air burst with no local fallout, the Trinity height-of-burst needed to be 580 feet (180 m).[76] With an air burst, the radioactive fission products rise into the stratosphere and become part of the global, rather than the local, environment. Air bursts were officially described as "self-cleansing."[77] There was no significant local fallout from Able.[78]

There was an intense transitory burst of fireball radiation lasting a few seconds. Many of the closer ships received doses of neutron and gamma radiation that could have been lethal to anyone on the ship, but the ships did not become radioactive. Neutron activation of materials in the ships was judged to be a minor problem by the standards of the time. One sailor on the support ship USS Haven was found to be "sleeping in a shower of gamma rays" from an illegal metal souvenir he had taken from a target ship. Fireball neutrons had made it radioactive.[79] Within a day nearly all the surviving target ships had been reboarded. The ship inspections, instrument recoveries, and moving and remooring of ships for the Baker test proceeded on schedule.[80]

Test animals

[edit]57 guinea pigs, 109 mice, 146 pigs, 176 goats, and 3,030 white rats had been placed on 22 target ships in stations normally occupied by people.[81] 35% of these animals died or were euthanised in the three months following the explosion: 10% were killed by the air blast, 15% were killed by radiation, and 10% were killed by the researchers as part of later study.[82] The most famous survivor was Pig #311, which was reportedly found swimming in the lagoon after the blast and was brought back to the National Zoo in Washington, DC.[83] The mysterious survival of Pig #311 caused some consternation at the time and has continued to be reported in error. However, an investigation pointed to the conclusion that it had neither swum in the ocean nor escaped the blast; it had likely been safely aboard an observation vessel during the test, thus "absent without leave" from its post on Sakawa and showing up about the same time other surviving pigs were captured.[84]

The high rate of test animal survival was due in part to the nature of single-pulse radiation. As with the two Los Alamos criticality accidents involving the earlier demon core, victims who were close enough to receive a lethal dose died, while those farther away recovered and survived. Also, all the mice were placed outside the expected lethal zone in order to study possible mutations in future generations.[86]

Although Gilda missed its target Nevada by nearly half a mile (800 meters), and it failed to sink or to contaminate the battleship, a crew would not have survived. Goat #119, tethered inside a gun turret and shielded by armor plate, received enough fireball radiation to die four days later of radiation sickness having survived two days longer than goat #53, which was on the deck, unshielded.[87] Had Nevada been fully manned, she would likely have become a floating coffin, dead in the water for lack of a live crew. Two years later she was finished off by an aerial torpedo 105 kilometres (65 mi) southwest of Pearl Harbor on 31 July 1948. In theory, every unprotected location on the ship received 100 sieverts (10,000 rem) of initial nuclear radiation from the fireball.[76] Therefore, people deep enough inside the ship to experience a 90% radiation reduction would still have received a lethal dose of 10 sieverts (1,000 rem).[88] In the assessment of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists:[16]

"a large ship, about a mile away from the explosion, would escape sinking, but the crew would be killed by the deadly burst of radiations from the bomb, and only a ghost ship would remain, floating unattended in the vast waters of the ocean."

Test Baker

[edit]

Detonation

[edit]In Baker on July 25, the weapon was suspended beneath landing craft LSM-60 anchored in the midst of the target fleet. Baker was detonated at 08:35,[25] 90 feet (27 m) underwater, halfway to the bottom in water 180 feet (55 m) deep. No identifiable part of LSM-60 was ever found; it was presumably vaporized by the nuclear fireball. Ten ships were sunk,[89] including the German heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, which sank in December, five months after the test, because radioactivity prevented repairs to a leak in the hull.[90]

Photographs of Baker are unique among nuclear detonation pictures. The searing, blinding flash that usually obscures the target area took place underwater and was barely seen. The clear image of ships in the foreground and background gives a sense of scale. The large condensation cloud and the vertical water column are distinctive Baker shot features. One picture shows a mark where the 27,000-ton battleship USS Arkansas was.[91]

As with Able, any ships that remained afloat within 1,000 yards (900 m) of the detonation were seriously damaged, but this time the damage came from below, from water pressure rather than air pressure. The greatest difference between the two shots was the radioactive contamination of all the target ships by Baker. Regardless of the degree of damage, only nine surviving Baker target ships were eventually decontaminated and sold for scrap. The rest were sunk at sea after decontamination efforts failed.[92]

Baker Target array

[edit]

| # | Name | Type | Distance from zero to bow |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | LSM-60 | Amphibious | 0 yd (0 m) |

| 3 | Arkansas | Battleship | 259 yd (237 m) |

| 8 | Pilotfish | Submarine | 363 yd (332 m) |

| 10 | Saratoga | Aircraft carrier | 446 yd (408 m) |

| 12 | YO-160 | Yard oiler | 543 yd (497 m) |

| 41 | Skipjack | Submarine | 808 yd (739 m) |

| 2 | Apogon | Submarine | 846 yd (774 m) |

| 7 | Nagato | Battleship | 852 yd (779 m) |

| 11 | ARDC-13 | Drydock | 1,276 yd (1,167 m) |

Prinz Eugen, ship #36, survived both the Able and Baker tests but was too radioactive to have leaks repaired. In September 1946 she was towed to Kwajalein Atoll, where she capsized in shallow water on December 22. She remains there today, with starboard propeller blades in the air.[94]

The submarine USS Skipjack was the only sunken ship successfully raised at Bikini.[95] She was towed to California and sunk again, as a target ship off the coast, two years later. [96]

Three other ships, all in sinking condition, were towed ashore at Bikini and beached:[97] attack transport USS Fallon, ship #25; destroyer USS Hughes, ship #27; and submarine USS Dentuda, ship #24. Dentuda, with her crew safely away from their submarine, being submerged (thus avoiding the base surge) and outside the 1000-yard circle, escaped serious contamination and hull damage and was successfully decontaminated, repaired, and briefly returned to service.[98][99][100]

Sequence of blast events

[edit]The Baker shot produced so many unusual phenomena that a conference was held two months later to standardize nomenclature and define new terms for use in descriptions and analysis.[101] The underwater fireball took the form of a rapidly expanding hot gas bubble that pushed against the water, generating a supersonic hydraulic shock wave which crushed the hulls of nearby ships as it spread out. Eventually it slowed to the speed of sound in water, which is one mile per second (1,600 m/s), five times faster than that of sound in air.[102] On the surface, the shock wave was visible as the leading edge of a rapidly expanding ring of dark water, called the "slick" for its resemblance to an oil slick.[103] Close behind the slick was a visually more dramatic but less destructive whitening of the water surface called the "crack".[104]

When the gas bubble's diameter equaled the water depth, 180 feet (55 m), it hit the sea floor and the sea surface simultaneously. At the bottom, it created a shallow crater 30 feet (9 m) deep and 2,000 feet (610 m) wide.[105] At the top, it pushed the water above it into a "spray dome", which burst through the surface like a geyser. Elapsed time since detonation was four milliseconds.[106]

During the first full second, the expanding bubble removed all the water within a 500-foot (150 m) radius and lifted two million tons[107] of spray and seabed sand into the air. As the bubble rose at 2,500 feet per second (760 m/s),[108] it stretched the spray dome into a hollow cylinder or chimney of spray called the "column", 6,000 feet (1,800 m) tall and 2,000 feet (600 m) wide, with walls 300 feet (90 m) thick.[109]

As soon as the bubble reached the air, it started a supersonic atmospheric shock wave which, like the crack, was more visually dramatic than destructive. Brief low pressure behind the shock wave caused instant fog which shrouded the developing column in a "Wilson cloud", also called a "condensation cloud", obscuring it from view for two seconds. The Wilson cloud started out hemispherical, expanded into a disk which lifted from the water revealing the fully developed spray column, then expanded into a doughnut shape and vanished. The Able shot also produced a Wilson cloud, but heat from the fireball dried it out more quickly.[109]

By the time the Wilson cloud vanished, the top of the column had become a "cauliflower", and all the spray in the column and its cauliflower was moving down, back into the lagoon. Although cloudlike in shape, the cauliflower was more like the top of a geyser where water stops moving upward and starts to fall. There was no mushroom cloud; nothing rose into the stratosphere.[110]

-

Crossroads Baker, showing the white surface "crack" under the ships, and the top of the hollow spray column protruding through the hemispherical Wilson cloud. Bikini Island beach is in the background.

-

The Wilson cloud lifts, revealing a vertical black object, larger than ships in the foreground. One popular (but discounted) theory claims that this was the upended battleship Arkansas;[111] in reality, the dark area is caused by Arkansas's hull interfering with the development of the spray column, creating a hole in the plume via its presence.[112]

-

The Wilson cloud has evaporated revealing the cauliflower atop the spray column. Two million tons of water spray fall back into the lagoon. The radioactive base surge is moving toward the ships.

Meanwhile, lagoon water rushing back into the space vacated by the rising gas bubble started a tsunami which lifted the ships as it passed under them. At 11 seconds after detonation, the first wave was 1,000 feet (300 m) from surface zero and 94 feet (29 m) high.[113] By the time it reached the Bikini Island beach, 3.5 miles (6 km) away, it was a nine-wave set with shore breakers up to 15 feet (5 m) high, which tossed landing craft onto the beach and filled them with sand.[114]

Twelve seconds after detonation, falling water from the column started to create a 900-foot (270 m) tall "base surge" resembling the mist at the bottom of a large waterfall. Unlike the water wave, the base surge rolled over rather than under the ships. Of all the bomb's effects, the base surge had the greatest consequence for most of the target ships, because it painted them with radioactivity that could not be removed.[113] Tactical nuclear warfare advocates described the base surge as generation of very high sea states (GVHSS) disregarding radiation to emphasize the physical damage capable of disabling communication and radar equipment on warship superstructures.[115]

Arkansas

[edit]Arkansas was the closest ship to the bomb other than the ship from which it was suspended. The underwater shock wave crushed the starboard side of her hull, which faced the bomb, and rolled the battleship over onto her port side. It also ripped off the two starboard propellers and their shafts, along with the rudder and part of the stern, shortening the hull by 25 feet (7.6 m).[116]

She was next seen by Navy divers the same year, lying upside down with her bow on the rim of the underwater bomb crater and stern angled toward the center. There was no sign of the superstructure or the big guns. The first diver to reach Arkansas sank up to his armpits in radioactive mud. When National Park Service divers returned in 1989 and 1990, the bottom was again firm-packed with sand, and the mud was gone. They were able to see the barrels of the forward guns, which had not been visible in 1946.[117]

All battleships are top-heavy and tend to settle upside down when they sink. Arkansas settled upside down, but a 1989 diver's sketch of the wreck shows hardly any of the starboard side of the hull, making it look like the ship is lying on her side. Most of the starboard side is present but severely compacted.[118]

The superstructure has not been found. It either was stripped off and swept away or is lying under the hull, crushed and buried under sand which flowed back into the crater, partially refilling it. The only diver access to the inside is a tight squeeze through the port side casemate, called the "aircastle." The National Park Service divers practiced on the similar casemate of the battleship USS Texas, a museum ship, before entering Arkansas in 1990.[119]

Contrary to popular belief, Arkansas was not lifted vertically by the blast of the weapon test. Forensic examination of the wreck during surveys since the test conclusively show that structural failure of hull plating along the starboard side allowed rapid flooding and capsized the ship.[112]

-

Battleship Arkansas upside down, 180 feet (55 m) deep in Bikini Lagoon. Diver's sketch from a 1989 National Park Service dive.

-

Port casemate of Arkansas in 1989, upside down against the bottom. The only diver's access into the ship, it was entered in 1946 and again in 1990.

-

A similar battleship, USS Texas, with casemate circled. At Bikini, everything that was above the lower deck guns of Arkansas is either missing or is buried in the sand.

Aircraft carriers

[edit]Saratoga, placed close to Baker, sank 7.5 hours after the underwater shock wave opened up leaks in the hull. Immediately after the shock wave passed, the water wave lifted the stern 43 feet (13 m) and the bow 29 feet (8.8 m), rocked the ship side to side, and crashed over her, sweeping all five moored airplanes off the flight deck and knocking the stack over onto the deck. She remained upright and outside the spray column but close enough to be drenched by radioactive water from the collapsing cauliflower head as well as by the base surge.[120] Blandy ordered tugs to tow the carrier to Enyu Island for beaching, but Saratoga and the surrounding water remained too radioactive for close approach until after she sank.[121] She settled upright on the bottom, with the top of her mast 40 feet (12 m) below the surface.[122]

USS Independence survived Able with spectacular damage to the flight deck.[123] She was moored far enough away from Baker to avoid further physical damage but was severely contaminated. She was towed to San Francisco,[124] where four years of decontamination experiments at the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard failed to produce satisfactory results. On January 29, 1951, she was scuttled near the Farallon Islands.[125]

-

Diver's sketch of USS Saratoga on the bottom of Bikini Lagoon. Starboard torpedo blister is crumpled.

-

USS Independence, ship #28, showing blast damage from Able, before Baker made her radioactive.

Fission-product radioactivity

[edit]Baker was the first nuclear explosion close enough to the surface to keep the radioactive fission products in the local environment. It was not "self-cleansing." The result was radioactive contamination of the lagoon and the target ships. While anticipated, it caused far greater problems than were expected.[126]

The Baker explosion produced about 3 pounds (1.4 kg) of fission products.[127][128] These fission products were thoroughly mixed with the two million tons of spray and seabed sand that were lifted into the spray column and its cauliflower head and then dumped back into the lagoon. Most of it stayed in the lagoon and settled to the bottom or was carried out to sea by the lagoon's internal tidal and wind-driven currents.[110]

A small fraction of the contaminated spray was thrown back into the air as the base surge. Unlike the Wilson cloud, a meteorological phenomenon in clean air, the base surge was a heavy fog bank of radioactive mist that rolled across all the target ships, coating their surfaces with fission products.[129] When the mist in the base surge evaporated, the base surge became invisible but continued to move away, contaminating ships several miles from the detonation point.[130]

Unmanned boats were the first vessels to enter the lagoon. Onboard instruments allowed remote-controlled radiation measurements to be made. When support ships entered the lagoon for evaluation, decontamination, and salvage activities, they steered clear of lagoon water hot spots detected by the drone boats. The standard for radiation exposure to personnel was the same as that used by the Manhattan Project: 0.1 roentgens per day.[131] Because of this constraint, only the five most distant target ships could be boarded on the first day.[132] The closer-in ships were hosed down by Navy fireboats using saltwater and flame retardants. The first hosing reduced radioactivity by half, but subsequent hosings were ineffective.[133] For most of the ships, reboarding had to wait until the short-lived radioisotopes decayed; ten days elapsed before the last of the targets could be boarded.[134]

In the first six days after Baker, when radiation levels were highest, 4,900 men boarded target ships.[135] Sailors tried to scrub off the radioactivity with brushes, water, soap, and lye. Nothing worked, short of sandblasting to bare metal.[133]

-

As the spray column falls, a radioactive "base surge," like mist at the bottom of a waterfall, moves out toward the target ships. Foreground ship (left) is the 725 feet (221 m) long Japanese battleship Nagato.

-

In a largely ineffective effort to wash off base surge contamination, a fireboat hoses down the battleship New York with radioactive lagoon water. The ship was outside the area of the above map.

-

Sailors scrubbing down the German cruiser Prinz Eugen with brushes, water, soap, and lye. Five months later, the ship was still too radioactive to permit repairs to a leak, and she sank.

Test animals

[edit]

Only pigs, goats and rats were used in the Baker test. All the pigs and most of the rats died. Several days elapsed before sailors were able to board the target ships where test animals were located; during that time the accumulated doses from the gamma rays produced by fission products became lethal for the animals.[136] Since much of the public interest in Operation Crossroads had focused on the fate of the test animals, in September Blandy asserted that radiation death is not painful: "The animal merely languishes and recovers or dies a painless death. Suffering among the animals as a whole was negligible."[137] This was clearly not true. While the well-documented suffering of Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin as they died of radiation injury at Los Alamos was still secret, the widely reported radiation deaths at Hiroshima and Nagasaki had not been painless. In 1908, Dr. Charles Allen Porter had stated in an academic paper, "the agony of inflamed X-ray lesions is almost unequalled in any other disease."[98]

Induced radioactivity

[edit]The Baker explosion ejected into the environment about twice as many free neutrons as there were fission events. A plutonium fission event produces, on average, 2.9 neutrons, most of which are consumed in the production of more fission, until fission falls off and the remaining uncaptured neutrons escape.[138] In an air burst, most of these environmental neutrons are absorbed by superheated air which rises into the stratosphere, along with the fission products and unfissioned plutonium. In the underwater Baker detonation, the neutrons were captured by seawater in the lagoon.[139]

Of the four major elements in seawater – hydrogen, oxygen, sodium, and chlorine – only sodium takes on intense, short-term radioactivity with the addition of a single neutron to its nucleus: common sodium-23 becomes radioactive sodium-24, with a 15-hour half-life. In six days, its intensity drops a thousandfold, but the corollary of short half-life is high initial intensity. Other isotopes were produced from seawater: hydrogen-3 (half-life 12 years) from hydrogen-2, oxygen-17 (stable) from oxygen-16, and chlorine-36 (half-life about 300,000 years) from chlorine-35, and some trace elements, but scarcity or low short-term intensity (long half-life) rendered them insignificant compared with sodium-24.[139]

Less than one pound of radioactive sodium was produced. If all the neutrons released by the fission of 2 pounds (0.91 kg) of plutonium-239 were captured by sodium-23, 0.4 pounds (0.18 kg) of sodium-24 would result, but sodium did not capture all the neutrons. Unlike fission products, which are heavy and eventually sank to the bottom of the lagoon, the sodium stayed in solution. It contaminated the hulls and onboard salt water systems of support ships that entered the lagoon, as well as the water used in decontamination.[139]

Unfissioned plutonium

[edit]The 10.6 pounds (4.8 kg) of plutonium which did not undergo fission and the 3 pounds (1.4 kg) of fission products were scattered.[140] Plutonium is not a biological hazard unless ingested or inhaled, and its alpha radiation cannot penetrate skin. Once inside the body it is significantly toxic both radiologically and chemically, having a heavy metal toxicity on a par with that of arsenic.[141] Estimates based on the Manhattan Project's "tolerance dose" of one microgram of plutonium per worker put 10.6 pounds at the equivalent of about five billion tolerable doses.[142]

Plutonium alpha rays could not be detected by the film badges and Geiger counters used by people who boarded the target ships because alpha particles have very low penetrating power, insufficient to enter the glass detection tube. It was assumed to be present in the environment wherever fission product radiation was detected. The decontamination plan was to scrub the target ships free of fission products and assume the plutonium would be washed away in the process. To see if this plan was working, samples of paint, rust, and other target ship surface materials were taken back to a laboratory on the support ship Haven and examined for plutonium.[143] The tests showed that the plan was not working. The results of these plutonium detection tests, and of tests performed on fish caught in the lagoon, caused all decontamination work to be abruptly terminated on August 10, effectively shutting down Operation Crossroads for safety reasons.[144] Tests conducted on the support ship USS Rockbridge in November indicated the presence of 2 milligrams (0.031 gr) of plutonium,[145] which represented 2,000 tolerable doses.[146]

Failed Baker cleanup and program termination

[edit]The program termination on August 10, sixteen days after Baker, was the result of a showdown between Dr. Stafford Warren, the Army colonel in charge of radiation safety for Operation Crossroads, and Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Special Weapons, Vice Admiral William H. P. Blandy. A radiation safety monitor under Warren's command later described him as "the only Army colonel who ever sank a Navy flotilla."[147]

Warren had been chief of the medical section of the Manhattan Project[148] and was in charge of radiation safety at the Trinity test,[149] as well as of the on-ground inspections at Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the bombings.[150] At Operation Crossroads, it was his job to keep the sailors safe during the cleanup.[151]

Radiation monitoring

[edit]

A total of 18,875 film badge dosimeters were issued to personnel during the operation. About 6,596 dosimeters were given to personnel who were based on the nearby islands or support ships that had no potential for radiation exposure. The rest were issued to all of the individuals thought to be at the greatest risk for radiological contamination along with a percentage of each group who were working in less contaminated areas. Personnel were removed for one or more days from areas and activities of possible exposure if their badges showed more than 0.1 roentgen (R) per day exposure. Experts believed at the time that this radiation dose could be tolerated by individuals for long periods without any harmful effects. The maximum accumulated dose of 3.72 R was received by a radiation safety monitor.[152]

Cleanup issues

[edit]The cleanup was hampered by two significant factors: the unexpected base surge and the lack of a viable cleanup plan. It was understood that if the water column fell back into the lagoon, which it did, any ships that were drenched by falling water might be contaminated beyond redemption. Nobody expected that to happen to almost the entire target fleet.[153] No decontamination procedures had been tested to see if they would work and to measure the potential risk to personnel. In the absence of a decontamination protocol, the ships were cleaned using traditional deck-scrubbing methods: hoses, mops, and brushes, with water, soap, and lye.[154] The sailors had no protective clothing.[155]

Secondary contamination

[edit]

By August 3, Colonel Warren concluded the entire effort was futile and dangerous.[156] The unprotected sailors were stirring up radioactive material and contaminating their skin, clothing, and, presumably, their lungs. When they returned to their support ship living quarters, they contaminated the shower stalls, laundry facilities, and everything they touched. Warren demanded an immediate halt to the entire cleanup operation. He was especially concerned about plutonium, which was undetectable on site.[157]

Warren also observed that the radiation safety procedures were not being followed correctly.[158] Fire boats got too close to the target ships they were hosing and drenched their crews with radioactive spray. One fire boat had to be taken out of service.[158] Film badges showed 67 overdoses between August 6 and 9.[147] More than half of the 320 Geiger counters available shorted out and became unavailable.[159] The crews of two target ships, USS Wainwright and USS Carteret, moored far from the detonation site, had moved back on board and become overexposed. They were immediately evacuated back to the United States.[160]

Captain L. H. Bibby, commanding officer of the apparently undamaged battleship New York, accused Warren's radsafe monitors of holding their Geiger counters too close to the deck.[147] He wanted to reboard his ship and sail it home. The steadily dropping radiation counts on the target ships gave an illusion that the cleanup was working, but Warren explained that although fission products were losing some of their gamma ray potency through radioactive decay, the ships were still contaminated. The danger of ingesting microscopic particles remained.[156]

Warren persuades Blandy

[edit]

Blandy ordered Warren to explain his position to 1,400 skeptical officers and sailors.[147] Some found him persuasive, but it was August 9 before he convinced Blandy. That was the date when Blandy realized, for the first time, that Geiger counters could not detect plutonium.[143] Blandy was aware of the health problems of radium dial painters who ingested microscopic amounts of radium in the 1920s, and the fact that plutonium was assumed to have a similar biological effect. When plutonium was discovered in the captain's quarters of Prinz Eugen, unaccompanied by fission products, Blandy realized that plutonium could be anywhere.[161]

The following day, August 10, Warren showed Blandy an autoradiograph of a fish, an x-ray picture made by radiation coming from the fish. The outline of the fish was made by alpha radiation from the fish scales, evidence that plutonium, mimicking calcium, had been distributed throughout the fish, out to the scales. Blandy announced his decision, "then we call it all to a halt." He ordered that all further decontamination work be discontinued.[144] Warren wrote home, "A self x ray of a fish ... did the trick."[144]

The decontamination failure ended plans to outfit some of the target ships for the 1947 Charlie shot and to sail the rest home in triumph. The immediate public relations problem was to avoid any perception that the entire target fleet had been destroyed. On August 6, in anticipation of this development, Blandy had told his staff that ships sunk or destroyed more than 30 days after the Baker shot "will not be considered as sunk by the bomb."[162] By then, public interest in Operation Crossroads was waning, and the reporters had gone home. The failure of decontamination did not make news until the final reports came out a year later.[163]

Test Charlie

[edit]

Testing program staff originally set test Charlie for early 1947. They wanted to explode it deep under the surface in the lee of the atoll to test the effect of nuclear weapons as depth charges on unmoored ships.[41] The unanticipated delays in decontaminating the target ships after test Baker[25] prevented the required technical support personnel from assisting with Charlie and also meant that there were no uncontaminated target ships available for use in Charlie. The naval weapons program staff decided the test was less pressing given that the entire U.S. arsenal had only a handful of nuclear weapons and canceled the test. The official reason given for canceling Charlie was that the program staff felt it was unnecessary because of the success of the Able and Baker tests.[164] The deep ocean effects testing that Charlie was to have performed were fulfilled nine years later with Operation Wigwam.[165]

Aftermath

[edit]All ships leak and require the regular operation of bilge pumps to stay afloat.[166] If their bilge pumps could not be operated, the target ships would eventually sink. Only one suffered this fate: Prinz Eugen, which sank in the Kwajalein lagoon on December 22. The rest were kept afloat long enough to be deliberately sunk or dismantled. After the August 10 decision to stop decontamination work at Bikini, the surviving target fleet was towed to Kwajalein Atoll where the live ammunition and fuel could be offloaded in uncontaminated water. The move was accomplished during the remainder of August and September.[167]

Eight of the major ships and two submarines were towed back to the United States and Hawaii for radiological inspection. Twelve target ships were so lightly contaminated that they were remanned and sailed back to the United States by their crews. Ultimately, only nine target ships were able to be scrapped rather than scuttled. The remaining target ships were scuttled off Bikini or Kwajalein Atolls, or near the Hawaiian Islands or the California coast during 1946–1948.[168] The remains of Independence were retained at Hunters Point Shipyard until 1951 to test decontamination methods.[169]: 6–24

The support ships were decontaminated as necessary and received a radiological clearance before they could return to the fleet. This required a great deal of experimentation at Navy shipyards in the United States, primarily in San Francisco at Hunters Point.[169]: 6–15 The destroyer USS Laffey required "sandblasting and painting of all underwater surfaces, and acid washing and partial replacement of salt-water piping and evaporators."[170]

A survey was conducted in mid-1947 to study long-term effects of the Operation Crossroads tests. According to the official report, decontamination efforts "revealed conclusively that removal of radioactive contamination of the type encountered in the target vessels in test Baker cannot be accomplished successfully."[171]

On August 11, 1947, Life summarized the report in a 14-page article with 33 pictures.[172] The article states, "If all the ships at Bikini had been fully manned, the Baker Day bomb would have killed 35,000 crewmen. If such a bomb were dropped below New York's Battery in a stiff south wind, 2 million people would die."[173]

The contamination problem was not widely appreciated by the general public until 1948, when No Place to Hide, a best-selling book by David Bradley, was serialized in the Atlantic Monthly, condensed by the Reader's Digest, and selected by the Book of the Month Club.[174] In his preface, Bradley, a key member of the Radiological Safety Section at Bikini known as the "Geiger men", asserted that "the accounts of the actual explosions, however well intended, were liberally seasoned with fantasy and superstition, and the results of the tests have remained buried in the vaults of military security."[175] His description of the Baker test and its aftermath brought to world attention the problem of radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons.[176]

Personnel exposure

[edit]

All Operation Crossroads operations were designed to keep personnel from being exposed to more than 0.1 roentgen (R) per day. At the time, this was considered to be an amount of radiation that could be tolerated for long periods without any harmful effects on health. Since there was no special clothing or radiation shielding available, the protection plan relied on managing who went where, when, and for how long.[38]

Radioactively "hot" areas were predicted and then checked with Geiger counters, sometimes by remote control, to see if they were safe. The level of measured gamma radiation determined how long personnel could operate in them without exceeding the allowable daily dose.[38] Instant gamma readings were taken by radiation safety specialists, but film-badge dosimeters, which could be read at the end of the day, were issued to all personnel believed to be at the greatest radiological risk. Anyone whose badge showed more than 0.1 R per day exposure was removed for one or more days from areas and activities of possible exposure. The maximum accumulated exposure recorded was 3.72 R, received by a radiation safety specialist.[38]

A percentage of each group working in less contaminated areas was badged. Eventually, 18,875 film-badge dosimeters were issued to about 15% of the total work force. On the basis of this sampling, a theoretical total exposure was calculated for each person who did not have a personal badge.[38] As expected, exposures for target ship crewmen who boarded their ships after Baker were higher than those for support ship crews. The hulls of support ships that entered the lagoon after Baker became so radioactive that sleeping quarters were moved toward the center of each ship.[177] Of the total mass of radioactive particles scattered by each explosion, 85% was unfissioned plutonium which produces alpha radiation not detected by film badges or Geiger counters. There was no method of detecting plutonium in a timely fashion, and participants were not monitored for ingestion of it.[139]

A summary of film badge readings (in roentgens) for July and August, when the largest number of personnel was involved, is listed below:

| Readings[38] | Total | 0 | 0.001–0.1 | 0.101–1.0 | 1.001–10.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July | 3,767 (100%) | 2,843 (75%) | 689 (18%) | 232 (6%) | 3 (<0.1%) |

| August | 6,664 (100%) | 3,947 (59%) | 2,139 (32%) | 570 (9%) | 8 (0.1%) |

Service members who participated in the cleanup of contaminated ships were exposed to unknown amounts of radiation. In 1996, a government-sponsored mortality study of Operation Crossroads veterans[178] showed that, by 1992, 46 years after the tests, veterans had experienced a 4.6% higher mortality than a control group of non-veterans. There were 200 more deaths among Operation Crossroads veterans than in the similar control group (12,520 vs. 12,320), implying a life-span reduction of about three months for Operation Crossroads veterans.[179] Veterans who were exposed to radiation formed the non-profit National Association of Atomic Veterans in 1978 to lobby for veterans benefits covering illnesses they believed were caused by their exposure.[178]

Legislation was passed in 1988 that removed the need for veterans to prove a causal link between certain forms of cancer and radiation exposure due to nuclear tests.[180] Incidence of the main expected causes of this increased mortality, leukemia and other cancers, was not significantly higher than normal. Death by those diseases was tabulated on the assumption that if radiation exposure had a life-shortening effect it would likely show up there, but it did not. Not enough data were gathered on other causes of death to determine the reason for this increase in all-cause mortality, and it remains a mystery. The mortality increase was higher, 5.7%, for those who boarded target ships after the tests than for those who did not, whose mortality increase was 4.3%.[178]

Bikini Atoll

[edit]

The 167 Bikini residents who were moved to the Rongerik Atoll prior to the Crossroads tests were unable to gather sufficient food or catch enough fish and shellfish to feed themselves in their new environment. The Navy left food and water for a few weeks and then failed to return in a timely manner. By January 1947, visitors to Rongerik reported the islanders were suffering malnutrition, facing potential starvation by July, and were emaciated by January 1948. In March 1948 they were evacuated to Kwajalein, and then settled onto another uninhabited island, Kili, in November. With only one third of a square mile, Kili has one sixth the land area of Bikini and, more importantly, has no lagoon and no protected harbor. Unable to practice their native culture of lagoon fishing, they became dependent on food shipments. Their 4,000 descendants today are living on several islands and in foreign countries.[33]

Their desire to return to Bikini was thwarted indefinitely by the U.S. decision to resume nuclear testing at Bikini in 1954. During 1954, 1956, and 1958, 21 more nuclear bombs were detonated at Bikini, yielding a total of 75 megatons of TNT (310 PJ), equivalent to more than 3,000 Baker bombs. Only one was an air burst, the 3.8 megaton Redwing Cherokee test. Air bursts distribute fallout in a large area, but surface bursts produce intense local fallout.[181] The first after Crossroads was the dirtiest: the 15 megaton Bravo shot of Operation Castle on March 1, 1954, which was the largest-ever U.S. test. Fallout from Bravo caused radiation injury to Bikini islanders who were living on Rongelap Atoll.[182]

The brief attempt to resettle Bikini from 1972 until 1978 was aborted when health problems from radioactivity in the food supply caused the atoll to be evacuated again. Sport divers who visit Bikini to dive on the shipwrecks must eat imported food. The local government elected to close the fly-in fly-out sports diving operation in Bikini lagoon in 2008,[183] and the 2009 diving season was canceled due to fuel costs, unreliable airline service to the island, and a decline in the Bikini Islanders' trust fund which subsidized the operation.[33] After a successful trial in October 2010, the local government licensed a sole provider of dive expeditions on the nuclear ghost fleet at Bikini Atoll starting in 2011. The aircraft carrier Saratoga is the primary attraction of a struggling, high-end sport diving industry.[34]

Legacy

[edit]Following test Baker decontamination problems, the United States Navy equipped newly constructed ships with a Countermeasure Wash Down System of piping and nozzles to cover exterior surfaces of the ship with a spray of salt water from the firefighting system when nuclear attack appeared imminent. The film of flowing water would theoretically prevent contaminants from settling into cracks and crevices.[184]

In popular culture

[edit]The juxtaposition of half-naked islanders with nuclear weapons that had the power to reduce everyone to a primitive state provided some with an inspirational motif. During Operation Crossroads, Paris swimwear designer Louis Réard adopted the name Bikini for his minimalist swimsuit design which, revolutionary for the time, exposed the wearer's navel. He explained that "like the bomb, the bikini is small and devastating".[185] Fashion writer Diana Vreeland described the bikini as the "atom bomb of fashion".[185] While two-piece swimsuits have been used since antiquity, it was Réard's name of the Bikini that stuck for all of its modern incarnations.[186]

Artist Bruce Conner made Crossroads, a 1976 video assembled from the official films, with an audio collage fashioned by Patrick Gleeson on a Moog synthesizer and a drone composition performed on an electric organ by Terry Riley. A commentator at The New York Review of Books called the experience of watching the video the "nuclear sublime."[187]

Films and TV shows have used archive footage of the test Baker explosion in a fictitious capacity. In the animated comedy series SpongeBob SquarePants, the footage is used three times; in the season 2 episode "Dying for Pie", in the season 5 episode "The Krusty Plate", and in the season 8 episode "Frozen Face-Off". One film example, TriStar Pictures' Godzilla from 1998, uses the Baker test footage in the film's opening to depict the atomic bomb responsible for the creation of the titular monster. In Godzilla Minus One, Operation Crossroads was the cause of Godzilla's mutation in the first place, with the film's novelisation elaborating that Baker was the specific detonation responsible. The test Baker explosion archival footage is also used in the Stanley Kubrick film Dr. Strangelove.[188] The footage plays during the ending montage of the movie accompanied by Vera Lynn singing "We'll Meet Again".[189]

See also

[edit]- Wōdejebato – a nearby seamount explored and mapped during these tests.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. ix.

- ^ Strauss 1962, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, pp. 19–22.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, p. 10.

- ^ a b Weisgall 1994, p. 16.

- ^ Peterson 1946, quoted in Weisgall 1994, p. 17.

- ^ Christman 1998, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Christman 1998, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 126.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 67.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Newson 1945, p. 4, quoted in Weisgall 1994, p. 216.

- ^ a b Bulletin Editors 1946, p. 1.

- ^ Delgado 1991, Ch 2.

- ^ Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J. (2005). American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 349–350. ISBN 978-0-375-41202-8. OCLC 56753298.

- ^ Szilard 1978, p. 184.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 90.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 94. Despite the postponement, only 13 members of Congress witnessed the Able test, and 7 witnessed the Baker test. Shurcliff 1947, p. 185.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 79.

- ^ Letter, Brig. Gen. T. J. Betts, USA, to Peter Brambir, March 21, 1946, filed in Protest Answers, National Archives Record Group 374. Cited in Delgado 1991, Ch 2.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b c d e f Daly 1986. The bomb yields are often reported as 21 kilotons, but the figure of 23 kilotons is used consistently throughout this article per Weisgall 1994, p. 186.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 117.

- ^ Parsons, Rear Admiral. "Subject: site for atomic bomb experiments, May 12, 1948." Appendix to U.S. Commanding Lieutenant General J. E. Hull's memorandum to the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, "Subject: location of proving ground for atomic weapons." Quoted in: Radioactive Heaven and Earth: The health and environmental effects of nuclear weapons testing in, on, and above the earth: A report of the IPPNW International Commission to Investigate the Health and Environmental Effects of Nuclear Weapons Production and the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (1991) p. 70 ISBN 0-945257-34-1. Accessed February 23, 2019

- ^ Bikini failed to meet one of the stipulated weather criteria: "predictable winds directionally uniform from sea level to 60,000 feet (18 km)." Daly 1986, p. 68.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, pp. 105, 106.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 107.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 113.

- ^ a b c * Niedenthal, Jack (2013), A Short History of the People of Bikini Atoll, retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ a b "Bikini Atoll Diving Charter". Indies Trader Marine Adventures. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, pp. 22–27.

- ^ a b Shurcliff 1946, p. 119.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d e f Navy History and Heritage Command 2002

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, p. 106.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, p. 33.

- ^ a b c Waters 1986, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, p. 32.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, p. 111.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, p. 9.

- ^ Network, News Corp Australia (July 26, 2016). "New footage reveals Bikini Atoll atomic bomb test aftermath". New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "NatlSecurityArchive on Twitter". Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "Video6". YouTube. Archived from the original on July 24, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ Bradley 1948, pp. 40, 91.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, pp. 109, 155.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 286.

- ^ "Atomic Goddess Revisited: Rita Hayworth's Bomb Image Found". CONELRAD Adjacent (blog). August 13, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, pp. 263–265.

- ^ a b United States Nuclear Tests: July 1945 through September 1992 (DOENV-209 REV15) (PDF) (Report). Las Vegas, NV: Department of Energy, Nevada Operations Office. December 1, 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 12, 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Yang, Xiaoping; North, Robert; Romney, Carl (August 2000). CMR Nuclear Explosion Database (Revision 3) (Report). SMDC Monitoring Research.

- ^ Norris, Robert Standish; Cochran, Thomas B. (February 1, 1994). "United States nuclear tests, July 1945 to 31 December 1992 (NWD 94-1)" (PDF). Nuclear Weapons Databook Working Paper. Washington, DC: Natural Resources Defense Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ Operation Crossroads, 1946 (DNA-6032F) (PDF) (Report). Defense Nuclear Agency. May 1, 1984. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c Sublette, Carey. "Nuclear Weapons Archive". Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "18.11.3 - B-29 44-27354, 58th Wing, 509th Composite Group aircraft that dropped the atomic bomb in Test Able of Operation Crossroads. Task Group 1.5 was the Army Air Force group of the task force and consisted of approximately 2,200 people. They were largely from SAC and were placed under the command of Brigadier General Roger M. Ramey, Commanding General of the 58th Bomb Wing. General Ramey's group was responsible for delivering the first Crossroads atomic bomb and provided the aircraft to photograph the explosion and collect scientific data.On July 1, 1946 Dave's Dream, a B-29 piloted by Major Woodrow P. Swancutt, assigned to the 509th Group temporarily stationed at Kwajalein, dropped an atomic bomb on 73 ships lying off of Bikini Island. Five ships were sunk and nine were badly damaged. Task Group 1.5 participated in the second phase of Operation Crossroads, the underwater explosion on July 25, 1946 by providing numerous aircraft for photographic, data collection, and support functions. Pilot Major Woodrow Swancutt is on the right1st Lt. Robert M. Glenn - Flight EngineerT/Sgt. Jack Cothran - Radio OperatorCpl. Herbert Lyons - Left ScannerCpl. Roland M. Medlin - Right ScannerCapt. William C. Harrison, Jr. - Co-PilotMajor Woodrow P. Swancutt - PilotMajor Harold H. Wood - BombardierCapt. Paul Chenchar, Jr. - Radar Operator | National Museum of Nuclear Science & History". nuclearmuseum.pastperfectonline.com. Retrieved April 9, 2025.

- ^ Campbell 2005, pp. 18, 186–189.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, pp. 130–135.

- ^ Delgado 1991, p. 26.

- ^ New York Times, July 1, 1946, p. 1.

- ^ New York Times, July 2, 1946, p. 3.

- ^ Delgado 1991, p. 86.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, p. 114.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 188.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Data in the table and the map come from Delgado 1991. The Able map is on p. 16, the Baker map on p. 17, and ship damage and distances on pp. 86–87. The full text of this reference is posted on the Internet (see link in Sources, below).

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 189.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, p. 165.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, pp. 165, 166, 168.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, p. 197.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 190.

- ^ Hansen 1995, p. 154, Vol 8, Table A-1. and Glasstone & Dolan 1977, pp. 409, 622.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1977.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, p. 143.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 193.

- ^ Bradley 1948, p. 70.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, pp. 218–221.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, p. 108.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, p. 140.

- ^ "Animals as Cold Warriors". Online Exhibit at the National Library of Medicine. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "Myth of Pig 311 Finally Cleared," Lewiston Daily Sun, July 22, 1946.

- ^ Life Editors 1947, p. 77. These two goats, on the attack transport Niagara, may have been far enough away to survive. Delgado 1991, p. 22.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, pp. 140–144.

- ^ Life Editors 1947, p. 76.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. 580.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, pp. 164–166.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, p. 275.

- ^ The upending was reported by Operation Crossroads participants and depicted in two contemporary drawings (see Battleship Arkansas Being Tossed in Giant Pillar), but two authors have suggested that what looks like the silhouette of a vertical battleship hull is actually a gap in the water column, an upside-down rain shadow, caused by the unseen, still-horizontal hull of Arkansas as it blocks the rise of water in the column. This explanation was described as a possibility in Shurcliff 1947, pp. 155, 156. Delgado stated it as a certainty in Delgado 1991, pp. 55, 88, and again in Delgado 1996, p. 75.

- ^ The fate of 13 small landing craft is unknown; they may have been sold for scrap, rather than scuttled. Delgado 1991, p. 33.

- ^ Shurcliff, William A. (November 18, 1946). "Technical Report of Operation Crossroads" (PDF). Defense Technical Information Center. Joint Task Force One. pp. 280–281. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ^ Delgado 1991, pp. 60–64. In 1978, her port propeller was salvaged and is preserved at the German Naval Memorial at Laboe.

- ^ Delgado 1996, p. 83.

- ^ "USS Skipjack (SS-184)". United States Navy. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ Delgado 1996, p. 87.

- ^ a b Weisgall 1994, p. 229.

- ^ "Dentuda (SS-335)". Naval History and Heritage Command. April 21, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2024.

- ^ Gaasterland, C.L. (1947). "OPERATION CROSSROADS. U.S.S. DENTUDA (SS335). TEST BAKER" (PDF). JOINT TASK FORCE ONE WASHINGTON DC. p. 10. Retrieved July 23, 2024.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, p. 151.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. 244.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. 48.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. 49.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. 251.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, pp. 49, 50.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, p. 156.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. 50.

- ^ a b Shurcliff 1947, pp. 150–156.

- ^ a b Weisgall 1994, p. 225.

- ^ Two video frames taken from the 1988 Robert Stone documentary film Radio Bikini, at times 42:44 and 42:45. Eyewitness reports at Weisgall 1994, pp. 162–163. On August 2, 1946, the Preliminary Statement of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Evaluation Board said, "From some of the photographs, it appears that this column lifted the 26,000-ton battleship Arkansas for a brief interval before the vessel plunged to the bottom of the lagoon. Confirmation of this must await the analysis of high-speed photographs which are not yet available". Shurcliff 1947, p. 196. The video frames shown here were first made public in 1988 when Robert Stone got permission to use them in his documentary film. They are viewable on the Internet at sonicbomb.com, 39 seconds into the video, "Baker". Retrieved November 3, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "National Park Service: The Archeology of the Atomic Bomb (Chapter 4)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Glasstone & Dolan 1977, p. 52.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, plate 29.

- ^ Brown, Peter J. (1986). "Blue-out and Nuclear Sea States". Proceedings. 112 (1). United States Naval Institute: 104&105.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, p. 151.

- ^ Delgado 1996, pp. 119, 120.

- ^ Delgado 1991, p. 95.

- ^ Delgado 1996, p. 117.

- ^ Delgado 1991, p. 101.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, p. 213.

- ^ Davis 1994.

- ^ Shurcliff 1946, pp. 154–157.

- ^ Weisgall 1994, p. 261.

- ^ "USS Independence (CVL-22)". United States Navy. Archived from the original on September 25, 2000. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ Memorandum, Col. A. W. Betts, USACOE, to Brig. Gen. K. D. Nichols, MED, USACOE, August 10, 1946, quoted in Delgado 1996, p. 87.

- ^ The conversion ratio of fission to energy is one pound (0.45 kg) of fission per eight kilotons of energy. The 23-kiloton yield of the Baker device indicates that just under three pounds (1.4 kg) of plutonium-239 became fission products.Glasstone 1967, p. 481.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, pp. 167, 168, & plate 28.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, p. 159.

- ^ Glasstone & Dolan 1977, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Delgado 1996, p. 85.

- ^ Delgado 1991, p. 28.

- ^ a b Delgado 1991, p. 29.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, p. 168.

- ^ Delgado 1996, p. 175.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Shurcliff 1947, p. 167.

- ^ Glasstone 1967, p. 486.

- ^ a b c d Delgado 1996, p. 86.

- ^ The total amount of plutonium in the core, later called the pit, was 13.6 pounds (6.2 kg), 3 pounds (1.4 kg) of which fissioned. Coster-Mullen 2003, p. 45.