Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Naval warfare

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river.

The armed forces branch designated for naval warfare is a navy. Naval operations can be broadly divided into riverine/littoral applications (brown-water navy), open-ocean applications (blue-water navy), between riverine/littoral and open-ocean applications (green-water navy), although these distinctions are more about strategic scope than tactical or operational division. The strategic offensive purpose of naval warfare is projection of force by water, and its strategic defensive purpose is to challenge the similar projection of force by enemies.

History

[edit]Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years.[1] Even in the interior of large landmasses, transportation before the advent of extensive railways was largely dependent upon rivers, lakes, canals, and other navigable waterways.

The latter were crucial in the development of the modern world in the United Kingdom, America, the Low Countries and northern Germany, because they enabled the bulk movement of goods and raw material, which supported the nascent Industrial Revolution. Prior to 1750, materials largely moved by river barge or sea vessels. Thus armies, with their exorbitant needs for food, ammunition and fodder, were tied to the river valleys throughout the ages.

Pre-recorded history (Homeric Legends, e.g. Troy), and classical works such as The Odyssey emphasize the sea. The Persian Empire – united and strong – could not prevail against the might of the Athenian fleet combined with that of lesser city states in several attempts to conquer the Greek city states. Phoenicia's and Egypt's power, Carthage's and even Rome's largely depended upon control of the seas.

So too did the Venetian Republic dominate Italy's city states, thwart the Ottoman Empire, and dominate commerce on the Silk Road and the Mediterranean in general for centuries. For three centuries, Vikings raided and pillaged far into central Russia and Ukraine, and even to distant Constantinople (both via the Black Sea tributaries, Sicily, and through the Strait of Gibraltar).

Gaining control of the sea has largely depended on a fleet's ability to wage sea battles. Throughout most of naval history, naval warfare revolved around two overarching concerns, namely boarding and anti-boarding. It was only in the late 16th century, when gunpowder technology had developed to a considerable extent, that the tactical focus at sea shifted to heavy ordnance.[2]

Many sea battles through history also provide a reliable source of shipwrecks for underwater archaeology. A major example is the exploration of the wrecks of various warships in the Pacific Ocean.

Mediterranean Sea

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2025) |

The first recorded sea battle was the Battle of the Delta, the Ancient Egyptians defeated the Sea Peoples in a sea battle c. 1175 BC.[3] As recorded on the temple walls of the mortuary temple of pharaoh Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, this repulsed a major sea invasion near the shores of the eastern Nile Delta using a naval ambush and archers firing from both ships and shore.

Assyrian reliefs from the 8th century BC show Phoenician fighting ships, with two levels of oars, fighting men on a sort of bridge or deck above the oarsmen, and some sort of ram protruding from the bow. No written mention of strategy or tactics seems to have survived.

Josephus Flavius (Antiquities IX 283–287) reports a naval battle between Tyre and the king of Assyria who was aided by the other cities in Phoenicia. The battle took place off the shores of Tyre. Although the Tyrian fleet was much smaller, the Tyrians defeated their enemies.

The Greeks of Homer just used their ships as transport for land armies, but in 664 BC there is a mention of a battle at sea between Corinth and its colony city Corcyra.

Ancient descriptions of the Persian Wars were the first to feature large-scale naval operations, not just sophisticated fleet engagements with dozens of triremes on each side, but combined land-sea operations. It seems unlikely that all this was the product of a single mind or even of a generation; most likely the period of evolution and experimentation was simply not recorded by history.

After some initial battles while subjugating the Greeks of the Ionian coast, the Persians determined to invade Greece proper. Themistocles of Athens estimated that the Greeks would be outnumbered by the Persians on land, but that Athens could protect itself by building a fleet (the famous "wooden walls"), using the profits of the silver mines at Laurium to finance them.

The first Persian campaign, in 492 BC, was aborted because the fleet was lost in a storm, but the second, in 490 BC, captured islands in the Aegean Sea before landing on the mainland near Marathon. Attacks by the Greek armies repulsed these.

The third Persian campaign in 480 BC, under Xerxes I of Persia, followed the pattern of the second in marching the army via the Hellespont while the fleet paralleled them offshore. Near Artemisium, in the narrow channel between the mainland and Euboea, the Greek fleet held off multiple assaults by the Persians, the Persians breaking through a first line, but then being flanked by the second line of ships. But the defeat on land at Thermopylae forced a Greek withdrawal, and Athens evacuated its population to nearby Salamis Island.

The ensuing Battle of Salamis was one of the decisive engagements of history. Themistocles trapped the Persians in a channel too narrow for them to bring their greater numbers to bear, and attacked them vigorously, in the end causing the loss of 200 Persian ships vs 40 Greek. Aeschylus wrote a play about the defeat, The Persians, which was performed in a Greek theatre competition a few years after the battle. It is the oldest known surviving play. At the end, Xerxes still had a fleet stronger than the Greeks, but withdrew anyway, and after losing at Plataea in the following year, returned to Asia Minor, leaving the Greeks their freedom. Nevertheless, the Athenians and Spartans attacked and burned the laid-up Persian fleet at Mycale, and freed many of the Ionian towns. These battles involved triremes or biremes as the standard fighting platform, and the focus of the battle was to ram the opponent's vessel using the boat's reinforced prow. The opponent would try to maneuver and avoid contact, or alternately rush all the marines to the side about to be hit, thus tilting the boat. When the ram had withdrawn and the marines dispersed, the hole would then be above the waterline and not a critical injury to the ship.

During the next fifty years, the Greeks commanded the Aegean, but not harmoniously. After several minor wars, tensions exploded into the Peloponnesian War (431 BC) between Athens' Delian League and the Spartan Peloponnese. Naval strategy was critical; Athens walled itself off from the rest of Greece, leaving only the port at Piraeus open, and trusting in its navy to keep supplies flowing while the Spartan army besieged it. This strategy worked, although the close quarters likely contributed to the plague that killed many Athenians in 429 BC.

There were a number of sea battles between galleys; at Rhium, Naupactus, Pylos, Syracuse, Cynossema, Cyzicus, Notium. But the end came for Athens in 405 BC at Aegospotami in the Hellespont, where the Athenians had drawn up their fleet on the beach, and were surprised by the Spartan fleet, who landed and burned all the ships. Athens surrendered to Sparta in the following year.

Navies next played a major role in the complicated wars of the successors of Alexander the Great.

The Roman Republic had never been much of a seafaring nation, but it had to learn. In the Punic Wars with Carthage, Romans developed the technique of grappling and boarding enemy ships with soldiers. The Roman Navy grew gradually as Rome became more involved in Mediterranean politics; by the time of the Roman Civil War and the Battle of Actium (31 BC), hundreds of ships were involved, many of them quinqueremes mounting catapults and fighting towers. Following the Emperor Augustus transforming the Republic into the Roman Empire, Rome gained control of most of the Mediterranean. Without any significant maritime enemies, the Roman navy was reduced mostly to patrolling for pirates and transportation duties. It was only on the fringes of the Empire, in newly gained provinces or defensive missions against barbarian invasion, that the navy still engaged in actual warfare.

Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa

[edit]While the barbarian invasions of the 4th century and later mostly occurred by land, some notable examples of naval conflicts are known. In the late 3rd century, in the reign of Emperor Gallienus, a large raiding party composed by Goths, Gepids and Heruli, launched itself in the Black Sea, raiding the coasts of Anatolia and Thrace, and crossing into the Aegean Sea, plundering mainland Greece (including Athens and Sparta) and going as far as Crete and Rhodes. In the twilight of the Roman Empire in the late 4th century, examples include that of Emperor Majorian, who, with the help of Constantinople, mustered a large fleet in a failed effort to expel the Germanic invaders from their recently conquered African territories, and a defeat of an Ostrogothic fleet at Sena Gallica in the Adriatic Sea.

During the Muslim conquests of the 7th century, Muslim fleets first appeared, raiding Sicily in 652 (see History of Islam in southern Italy and Emirate of Sicily), and defeating the Byzantine Navy in 655. Constantinople was saved from a prolonged Arab siege in 678 by the invention of Greek fire, an early form of flamethrower that was devastating to the ships in the besieging fleet. These were the first of many encounters during the Byzantine-Arab Wars.

The Caliphate became the dominant naval power in the Mediterranean Sea from the 7th to 13th centuries, during what is known as the Islamic Golden Age. One of the most significant inventions in medieval naval warfare was the torpedo, invented in Syria by the Arab inventor Hasan al-Rammah in 1275. His torpedo ran on water with a rocket system filled with explosive gunpowder materials and had three firing points. It was an effective weapon against ships.[6]

In the 8th century the Vikings appeared, although their usual style was to appear quickly, plunder, and disappear, preferably attacking undefended locations. The Vikings raided places along the coastline of England and France, with the greatest threats being in England. They would raid monasteries for their wealth and lack of formidable defenders. They also utilized rivers and other auxiliary waterways to work their way inland in the eventual invasion of Britain. They wreaked havoc in Northumbria and Mercia and the rest of Anglia before being halted by Wessex. King Alfred the Great of England was able to stay the Viking invasions with a pivotal victory at the Battle of Edington. Alfred defeated Guthrum, establishing the boundaries of Danelaw in an 884 treaty. The effectiveness of Alfred's 'fleet' has been debated; Kenneth Harl has pointed out that as few as eleven ships were sent to combat the Vikings, only two of which were not beaten back or captured.[citation needed]

The Vikings also fought several sea battles among themselves. This was normally done by binding the ships on each side together, thus essentially fighting a land battle on the sea.[1] However the fact that the losing side could not easily escape meant that battles tended to be hard and bloody. The Battle of Svolder is perhaps the most famous of these battles.

As Muslim power in the Mediterranean began to wane, the Italian trading towns of Genoa, Pisa, and Venice stepped in to seize the opportunity, setting up commercial networks and building navies to protect them. At first the navies fought with the Arabs (off Bari in 1004, at Messina in 1005), but then they found themselves contending with Normans moving into Sicily, and finally with each other. The Genoese and Venetians fought four naval wars, in 1253–1284, 1293–1299, 1350–1355, and 1378–1381. The last ended with a decisive Venetian victory, giving it almost a century to enjoy Mediterranean trade domination before other European countries began expanding into the south and west.

In the north of Europe, the near-continuous conflict between England and France was characterised by raids on coastal towns and ports along the coastlines and the securing of sea lanes to protect troop–carrying transports. The Battle of Dover in 1217, between a French fleet of 80 ships under Eustace the Monk and an English fleet of 40 under Hubert de Burgh, is notable as the first recorded battle using sailing ship tactics. The battle of Arnemuiden (23 September 1338), which resulted in a French victory, marked the opening of the Hundred Years War and was the first battle involving artillery.[7] However the battle of Sluys, fought two years later, saw the destruction of the French fleet in a decisive action which allowed the English effective control of the sea lanes and the strategic initiative for much of the war.

Eastern, Southern, and Southeast Asia

[edit]

The Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties of China were involved in several naval affairs over the triple set of polities ruling medieval Korea (Three Kingdoms of Korea), along with engaging naval bombardments on the peninsula from Asuka period Yamato Kingdom (Japan).

The Tang dynasty aided the Korean kingdom of Silla (see also Unified Silla) and expelled the Korean kingdom of Baekje which were supported by Japanese naval forces from the Korean peninsula (see Battle of Baekgang) and helped Silla overcome its rival Korean kingdoms, Baekje and Goguryeo, by 668. In addition, the Tang had maritime trading, tributary, and diplomatic ties as far as modern Sri Lanka, India, Islamic Iran and Arabia, as well as Somalia in East Africa.

From the Axumite Kingdom in modern-day Ethiopia, the Arab traveller Sa'd ibn Abi-Waqqas sailed from there to Tang China during the reign of Emperor Gaozong. Two decades later, he returned with a copy of the Quran, establishing the first Islamic mosque in China, the Mosque of Remembrance in Guangzhou. A rising rivalry followed between the Arabs and Chinese for control of trade in the Indian Ocean. In his book Cultural Flow Between China and the Outside World, Shen Fuwei notes that maritime Chinese merchants in the 9th century were landing regularly at Sufala in East Africa to cut out Arab middle-men traders.[8]

The Chola dynasty of medieval India was a dominant seapower in the Indian Ocean, an avid maritime trader and diplomatic entity with Song China. Rajaraja Chola I (reigned 985 to 1014) and his son Rajendra Chola I (reigned 1014–42), sent a great naval expedition that occupied parts of Myanmar, Malaya, and Sumatra.

In the Nusantara archipelago, large ocean going ships of more than 50 m in length and 5.2–7.8 meters freeboard are already used at least since the 2nd century AD, contacting India to China.[9]: 347 [10]: 41 Srivijaya empire since the 7th century AD controlled the sea of the western part of the archipelago. The Kedukan Bukit inscription is the oldest record of Indonesian military history, and noted a 7th-century Srivijayan sacred siddhayatra journey led by Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa. He was said to have brought 20,000 troops, including 312 people in boats and 1,312 foot soldiers.[11]: 4 The 10th century Arab text Ajayeb al-Hind (Marvels of India) gives an account of an invasion in Africa by people called Wakwak or Waqwaq,[12]: 110 probably the Malay people of Srivijaya or Javanese people of Mataram kingdom,[13]: 27 [14]: 39 in 945–946 CE. They arrived at the coast of Tanganyika and Mozambique with 1000 boats and attempted to take the citadel of Qanbaloh, though eventually failed. The reason of the attack is because that place had goods suitable for their country and for China, such as ivory, tortoise shells, panther skins, and ambergris, and also because they wanted black slaves from Bantu people (called Zeng or Zenj by Arabs, Jenggi by Javanese) who were strong and make good slaves.[12]: 110 Before the 12th century, Srivijaya is primarily land-based polity rather than maritime power, fleets are available but acted as logistical support to facilitate the projection of land power. Later, the naval strategy degenerated to raiding fleet. Their naval strategy was to coerce merchant ships to dock in their ports, which if ignored, they will send ships to destroy the ship and kill the occupants.[15][16]

In 1293, the Mongol Yuan dynasty launched an invasion to Java. The Yuan sent 500–1000 ships and 20,000–30,000 soldiers, but was ultimately defeated on land by surprise attack, forcing the army to fall back to the beach. In the coastal waters, Javanese junks had already attacked the Mongol ships. After all of the troops had boarded the ships on the coast, the Yuan army battled the Javanese fleet. After repelling it, they sailed back to Quanzhou. Javanese naval commander Aria Adikara intercepted a further Mongol invasion.[17]: 145 [14]: 107–110 Although with only scarce information, travellers passing the region, such as Ibn Battuta and Odoric of Pordenone noted that Java had been attacked by the Mongols several times, always ending in failure.[18][19] After those failed invasions, Majapahit empire quickly grew and became the dominant naval power in the 14–15th century. The usage of cannons in the Mongol invasion of Java,[20]: 245 led to deployment of cetbang cannons by Majapahit fleet in 1300s.[21] The main warship of Majapahit navy was the jong. The jongs were large transport ships which could carry 100–2000 tons of cargo and 50–1000 people, 28.99–88.56 meter in length.[22]: 60–62 The exact number of jong fielded by Majapahit is unknown, but the largest number of jong deployed in an expedition is about 400 jongs, when Majapahit attacked Pasai, in 1350.[23] In this era, even to the 17th century, the Nusantaran naval soldiers fought on a platform on their ships called balai and performed boarding actions. Scattershots fired from cetbang are used to counter this type of fighting, fired at personnel.[20]: 241 [24]: 162

In the 12th century, China's first permanent standing navy was established by the Southern Song dynasty, the headquarters of the Admiralty stationed at Dinghai. This came about after the conquest of northern China by the Jurchen people (see Jin dynasty) in 1127, while the Song imperial court fled south from Kaifeng to Hangzhou. Equipped with the magnetic compass and knowledge of Shen Kuo's famous treatise (on the concept of true north), the Chinese became proficient experts of navigation in their day. They raised their naval strength from a mere 11 squadrons of 3,000 marines to 20 squadrons of 52,000 marines in a century's time.

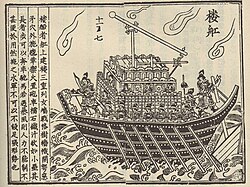

Employing paddle wheel crafts and trebuchets throwing gunpowder bombs from the decks of their ships, the Southern Song dynasty became a formidable foe to the Jin dynasty during the 12th–13th centuries during the Jin–Song Wars. There were naval engagements at the Battle of Caishi and Battle of Tangdao.[25][26] With a powerful navy, China dominated maritime trade throughout South East Asia as well. Until 1279, the Song were able to use their naval power to defend against the Jin to the north, until the Mongols finally conquered all of China. After the Song dynasty, the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China was a powerful maritime force in the Indian Ocean.

The Yuan emperor Kublai Khan attempted to invade Japan twice with large fleets (of both Mongols and Chinese), in 1274 and again in 1281, both attempts being unsuccessful (see Mongol invasions of Japan). Building upon the technological achievements of the earlier Song dynasty, the Mongols also employed early cannons upon the decks of their ships.[27][page needed]

While Song China built its naval strength, the Japanese also had considerable naval prowess. The strength of Japanese naval forces could be seen in the Genpei War, in the large-scale Battle of Dan-no-ura on 25 April 1185. The forces of Minamoto no Yoshitsune were 850 ships strong, while Taira no Munemori had 500 ships.

In the mid-14th century, the rebel leader Zhu Yuanzhang (1328–1398) seized power in the south amongst many other rebel groups. His early success was due to capable officials such as Liu Bowen and Jiao Yu, and their gunpowder weapons (see Huolongjing). Yet the decisive battle that cemented his success and his founding of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) was the Battle of Lake Poyang, considered one of the largest naval battles in history.[27]: 228–231

In the 15th century, the Chinese admiral Zheng He was assigned to assemble a massive fleet for several diplomatic missions abroad, sailing throughout the waters of the South East Pacific and the Indian Ocean. During his missions, on several occasions Zheng's fleet came into conflict with pirates. Zheng's fleet also became involved in a conflict in Sri Lanka, where the King of Ceylon traveled back to Ming China afterwards to make a formal apology to the Yongle Emperor.

The Ming imperial navy defeated a Portuguese navy led by Martim Afonso de Sousa in 1522. The Chinese destroyed one vessel by targeting its gunpowder magazine, and captured another Portuguese ship.[28][29] A Ming army and navy led by Koxinga defeated a western power, the Dutch East India Company, at the Siege of Fort Zeelandia, the first time China had defeated a western power.[30] The Chinese used cannons and ships to bombard the Dutch into surrendering.[31][32]

In the Sengoku period of Japan, Oda Nobunaga unified the country by military power. However, he was defeated by the Mōri clan's navy. Nobunaga invented the Tekkosen (large Atakebune equipped with iron plates) and defeated 600 ships of the Mōri navy with six armored warships (Battle of Kizugawaguchi). The navy of Nobunaga and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi employed clever close-range tactics on land with arquebus rifles, but also relied upon close-range firing of muskets in grapple-and-board style naval engagements. When Nobunaga died in the Honnō-ji incident, Hideyoshi succeeded him and completed the unification of the whole country. In 1592, Hideyoshi ordered the daimyōs to dispatch troops to Joseon Korea to conquer Ming China. The Japanese army which landed at Pusan on 12 April 1502 occupied Seoul within a month.[33] The Korean king escaped to the northern region of the Korean peninsula and Japan completed occupation of Pyongyang in June. The Korean navy then led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin defeated the Japanese navy in consecutive naval battles, namely Okpo, Sacheon, Tangpo and Tanghangpo.[34] The Battle of Hansando on 14 August 1592 resulted in a decisive victory for Korea over the Japanese navy.[35] In this battle, 47 Japanese warships were sunk and 12 other ships were captured whilst no Korean warship was lost.[36] The defeats in the sea prevented the Japanese navy from providing their army with appropriate supply.[37]

Yi Sun-sin was later replaced with Admiral Wŏn Kyun, whose fleets faced a defeat.[38] The Japanese army, based near Busan, overwhelmed the Korean navy in the Battle of Chilcheollyang on 28 August 1597 and began advancing toward China. This attempt was stopped when the reappointed Admiral Yi, won the battle of Myeongnyang.[39]

The Wanli Emperor of Ming China sent military forces to the Korean peninsula. Yi Sun-sin and Chen Lin continued to successfully engage the Japanese navy with 500 Chinese warships and the strengthened Korean fleet.[40][41][42] In 1598, the planned conquest in China was canceled by the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and the Japanese military retreated from the Korean Peninsula. On their way back to Japan, Yi Sun-sin and Chen Lin attacked the Japanese navy at the Battle of Noryang inflicting heavy damages, but the Chinese top official Deng Zilong and the Korean commander Yi Sun-sin were killed in a Japanese army counterattack. The rest of the Japanese army returned to Japan by the end of December.[43] In 1609, the Tokugawa shogunate ordered the abandonment of warships to the feudal lord. The Japanese navy stagnated until the Meiji period.

In Korea, the greater range of Korean cannons, along with the brilliant naval strategies of the Korean admiral Yi Sun-sin, were the main factors in the ultimate Japanese defeat. Yi Sun-sin is credited for improving the Geobukseon (turtle ship), which were used mostly to spearhead attacks. They were best used in tight areas and around islands rather than on the open sea. Yi Sun-sin effectively cut off the possible Japanese supply line that would have run through the Yellow Sea to China, and severely weakened the Japanese strength and fighting morale in several heated engagements (many regard the critical Japanese defeat to be the Battle of Hansan Island). The Japanese faced diminishing hopes of further supplies due to repeated losses in naval battles in the hands of Yi Sun-sin. As the Japanese army was about to return to Japan, Yi Sun-sin decisively defeated a Japanese navy at the Battle of Noryang.

Ancient and Medieval China

[edit]

In ancient China, the first known naval battles took place during the Warring States period (481–221 BC) when vassal lords battled one another. Chinese naval warfare in this period featured grapple-and-hook, as well as ramming tactics with ships called "stomach strikers" and "colliding swoopers".[44] It was written in the Han dynasty that the people of the Warring States era had employed chuan ge ships (dagger-axe ships, or halberd ships), thought to be a simple description of ships manned by marines carrying dagger-axe halberds as personal weapons.

The 3rd-century writer Zhang Yan asserted that the people of the Warring States period named the boats this way because halberd blades were actually fixed and attached to the hull of the ship in order to rip into the hull of another ship while ramming, to stab enemies in the water that had fallen overboard and were swimming, or simply to clear any possible dangerous marine animals in the path of the ship (since the ancient Chinese did believe in sea monsters; see Xu Fu for more info).

Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of the Qin dynasty (221–207 BC), owed much of his success in unifying southern China to naval power, although an official navy was not yet established (see Medieval Asia section below). The people of the Zhou dynasty were known to use temporary pontoon bridges for general means of transportation, but it was during the Qin and Han dynasties that large permanent pontoon bridges were assembled and used in warfare (first written account of a pontoon bridge in the West being the oversight of the Greek Mandrocles of Samos in aiding a military campaign of Persian emperor Darius I over the Bosporus).

During the Han dynasty (202 BC–220 AD), the Chinese began using the stern-mounted steering rudder, and they also designed a new ship type, the junk. From the late Han dynasty to the Three Kingdoms period (220–280 AD), large naval battles such as the Battle of Red Cliffs marked the advancement of naval warfare in the East. In the latter engagement, the allied forces of Sun Quan and Liu Bei destroyed a large fleet commanded by Cao Cao in a fire-based naval attack.

In terms of seafaring abroad, arguably one of the first Chinese to sail into the Indian Ocean and to reach Sri Lanka and India by sea was the Buddhist monk Faxian in the early 5th century, although diplomatic ties and land trade to Persia and India were established during the earlier Han dynasty. However, Chinese naval maritime influence would penetrate into the Indian Ocean until the medieval period.

Early modern

[edit]

The late Middle Ages saw the development of the cogs, caravels and carracks ships capable of surviving the tough conditions of the open ocean, with enough backup systems and crew expertise to make long voyages routine.[1] In addition, they grew from 100 tons to 300 tons displacement, enough to carry cannon as armament and still have space for cargo. One of the largest ships of the time, the Great Harry, displaced over 1,500 tons.

The voyages of discovery were fundamentally commercial rather than military in nature, although the line was sometimes blurry in that a country's ruler was not above funding exploration for personal profit, nor was it a problem to use military power to enhance that profit. Later the lines gradually separated, in that the ruler's motivation in using the navy was to protect private enterprise so that they could pay more taxes.

Like the Egyptian Shia-Fatimids and Mamluks, the Sunni-Islamic Ottoman Empire centered in modern-day Turkey dominated the eastern Mediterranean Sea. The Ottomans built a powerful navy, rivaling the Italian city-state of Venice during the Ottoman–Venetian War (1499–1503).

Although they were sorely defeated in the Battle of Lepanto (1571) by the Holy League, the Ottomans soon rebuilt their naval strength, and afterwards successfully defended the island of Cyprus so that it would stay in Ottoman hands. However, with the concurrent Age of Discovery, Europe had far surpassed the Ottoman Empire, and successfully bypassed their reliance on land-trade by discovering maritime routes around Africa and towards the Americas.

The first naval action in defense of the new colonies was just ten years after Vasco da Gama's epochal landing in India. In March 1508, a combined Gujarati/Egyptian force surprised a Portuguese squadron at Chaul, and only two Portuguese ships escaped. The following February, the Portuguese viceroy destroyed the allied fleet at Diu, confirming Portuguese domination of the Indian Ocean.

In 1582, the Battle of Ponta Delgada in the Azores, in which a Spanish-Portuguese fleet defeated a combined French and Portuguese force, with some English direct support, thus ending the Portuguese succession crisis, was the first battle fought in mid-Atlantic.

In 1588, Spanish King Philip II sent his Armada to subdue the English fleet of Elizabeth, but Admiral Sir Charles Howard defeated the Armada, marking the rise to prominence of the English Royal Navy. However it was unable to follow up with a decisive blow against the Spanish navy, which remained the most important for another half century. After the war's end in 1604 the English fleet went through a time of relative neglect and decline.

In the 16th century, the Barbary states of North Africa rose to power, becoming a dominant naval power in the Mediterranean Sea due to the Barbary pirates. The coastal villages and towns of Italy, Spain and Mediterranean islands were frequently attacked, and long stretches of the Italian and Spanish coasts were almost completely abandoned by their inhabitants; after 1600 Barbary pirates occasionally entered the Atlantic and struck as far north as Iceland.

According to Robert Davis[45][46] as many as 1.25 million Europeans were captured by Barbary pirates and sold as slaves in North Africa and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 19th centuries. These slaves were captured mainly from seaside villages in Italy, Spain and Portugal, and from farther places like France, England, the Netherlands, Ireland and even Iceland and North America. The Barbary pirates were also able to successfully defeat and capture many European ships, largely due to advances in sailing technology by the Barbary states. The earliest naval trawler, xebec and windward ships were employed by the Barbary pirates from the 16th century.[47]

From the middle of the 17th century competition between the expanding English and Dutch commercial fleets came to a head in the Anglo-Dutch Wars, the first wars to be conducted entirely at sea. Very few ships were sunk in naval combat during the Anglo-Dutch wars, as it was difficult to hit ships below the water level; the water surface deflected cannonballs, and the few holes produced could be patched quickly. Naval cannonades damaged men and sails more than they sunk ships. Three wars were fought between England and the Dutch Republic during the 17th century, though the Glorious Revolution put an end to further Anglo-Dutch conflicts for almost a century.[48][49]

Late modern

[edit]18th century

[edit]

The 18th century developed into a period of seemingly continuous international wars, each larger than the last. At sea, the British and French were bitter rivals; the French aided the fledgling United States in the American Revolutionary War, but their strategic purpose was to capture territory in India and the West Indies – which they did not achieve. In the Baltic Sea, the final attempt to revive the Swedish Empire led to Gustav III's Russian War, with its grande finale at the Second Battle of Svensksund. The battle, unrivaled in size until the 20th century, was a decisive Swedish tactical victory, but it resulted in little strategical result, due to poor army performance and previous lack of initiative from the Swedes, and the war ended with no territorial changes.

Even the change of government due to the French Revolution seemed to intensify rather than diminish the rivalry, and the Napoleonic Wars included a series of legendary naval battles, culminating in the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, by which Admiral Horatio Nelson broke the power of the French and Spanish fleets, but lost his own life in so doing.

19th century

[edit]

Trafalgar ushered in the Pax Britannica of the 19th century, marked by general peace in the world's oceans, under the ensigns of the Royal Navy. But the period was one of intensive experimentation with new technology; steam power for ships appeared in the 1810s, improved metallurgy and machining technique produced larger and deadlier guns, and the development of explosive shells, capable of demolishing a wooden ship at a single blow, in turn required the addition of iron armour.

Although naval power during the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties established China as a major world seapower in the East, the Qing dynasty lacked an official standing navy. They were more interested in pouring funds into military ventures closer to home (China proper), such as Mongolia, Tibet, and Central Asia (modern Xinjiang). However, there were some considerable naval conflicts involving the Qing navy before the First Opium War (such as the Battle of Penghu, and the capture of Formosa from Ming loyalists).

The Qing navy proved woefully undermatched during the First and Second Opium Wars, leaving China open to de facto foreign domination; portions of the Chinese coastline were placed under Western and Japanese spheres of influence. The Qing government responded to its defeat in the Opium Wars by attempting to modernize the Chinese navy; placing several contracts in European shipyards for modern warships. The result of these developments was the Beiyang Fleet, which was dealt a severe blow by the Imperial Japanese Navy in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895).

The battle between CSS Virginia and USS Monitor in the American Civil War was a duel of ironclads that symbolized the changing times. The first fleet action between ironclad ships was fought in 1866 at the Battle of Lissa between the navies of Austria and Italy. Because the decisive moment of the battle occurred when the Austrian flagship SMS Erzherzog Ferdinand Max successfully sank the Italian flagship Re d'Italia by ramming, in subsequent decade every navy in the world largely focused on ramming as the main tactic. The last known use of ramming in a naval battle was in 1915, when HMS Dreadnought rammed the (surfaced) German submarine, U-29. The last surface ship sunk by ramming happened in 1879 when the Peruvian ship Huáscar rammed the Chilean ship Esmeralda. The last known warship equipped with a ram was launched in 1908, the German light cruiser SMS Emden.

With the advent of the steamship, it became possible to create massive gun platforms and to provide them with heavy armor resulting in the first modern battleships. The Battles of Santiago de Cuba and Tsushima demonstrated the power of these ships.

20th century

[edit]

In the early 20th century, the modern battleship emerged: a steel-armored ship, entirely dependent on steam propulsion, with a main battery of uniform caliber guns mounted in turrets on the main deck. This type was pioneered in 1906 with HMS Dreadnought which mounted a main battery of ten 12-inch (300 mm) guns instead of the mixed caliber main battery of previous designs. Along with her main battery, Dreadnought and her successors retained a secondary battery for use against smaller ships like destroyers and torpedo boats and, later, aircraft.

Dreadnought style battleships dominated fleets in the early 20th century. They would play major parts in both the Russo-Japanese War and World War I. The Russo-Japanese War saw the rise of the Imperial Japanese Navy after their underdog victory against the waning Imperial Russian Navy at the Battle of Tsushima; while WWI pitted the old Royal Navy against the new Kaiserliche Marine of Imperial Germany, culminating in the 1916 Battle of Jutland. The future was heralded when the seaplane carrier HMS Engadine and her Short 184 seaplanes joined the battle. In the Black Sea, Russian seaplanes flying from a fleet of converted carriers interdicted Turkish maritime supply routes, Allied air patrols began to counter German U-boat activity in Britain's coastal waters, and a British Short 184 carried out the first successful torpedo attack on a ship.

In 1918 the Royal Navy converted an Italian liner to create the first aircraft carrier, HMS Argus, and shortly after the war the first purpose-built carrier, HMS Hermes was launched. Many nations agreed to the Washington Naval Treaty and scrapped many of their battleships and cruisers while still in the shipyards, but the growing tensions of the 1930s restarted the building programs, with even larger ships. The Yamato-class battleships, the largest ever, displaced 72,000 tons and mounted 18.1-inch (460 mm) guns.

The victory of the Royal Navy at the Battle of Taranto was a pivotal point as this was the first true demonstration of naval air power. The importance of naval air power was further reinforced by the Attack on Pearl Harbor, which forced the United States to enter World War II. Nevertheless, in both Taranto and Pearl Harbor, the aircraft mainly attacked stationary battleships. The sinking of the British battleships HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse, which were in full combat manoeuvring at the time of the attack, finally marked the end of the battleship era.[50] Aircraft and their transportation, the aircraft carrier, came to the fore.

During the Pacific War of World War II, battleships and cruisers spent most of their time escorting aircraft carriers and bombarding shore positions, while the carriers and their airplanes were the stars of the Battle of the Coral Sea,[51] Battle of Midway,[51] Battle of the Eastern Solomons,[52] Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands[52] and Battle of the Philippine Sea. The engagements between battleships and cruisers, such as the Battle of Savo Island and the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, were limited to night-time actions in order to avoid exposure to air attacks.[53] Nevertheless, battleships played the key role again in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, even though it happened after the major carrier battles, mainly because the Japanese carrier fleet was by then essentially depleted. It was the last naval battle between battleships in history.[54] Air power remained key to navies throughout the 20th century, moving to jets launched from ever-larger carriers, and augmented by cruisers armed with guided missiles and cruise missiles.

Roughly parallel to the development of naval aviation was the development of submarines to attack underneath the surface. At first, the ships were capable of only short dives, but they eventually developed the capability to spend weeks or months underwater powered by nuclear reactors. In both world wars, submarines (U-boats in Germany) primarily exerted their power by using torpedoes to sink merchant ships and other warships. In the 1950s, the Cold War inspired the development of ballistic missile submarines, each loaded with dozens of thermonuclear weapon-armed SLBMs and with orders to launch them from sea if the other nation attacked.

Against the backdrop of those developments, World War II had seen the United States become the world's dominant sea power. Throughout the rest of the 20th century, the United States Navy maintained a tonnage greater than that of the next 17 largest navies combined.[55]

The aftermath of World War II saw naval gunnery supplanted by ship to ship missiles as the primary weapon of surface combatants. Two major naval battles have taken place since World War II.

The Indo-Pakistani Naval War of 1971 was the first major naval war post World War II. It saw the dispatch of an Indian aircraft carrier group, heavy utilisation of missile boats in naval operations, total naval blockade of Pakistan by the Indian Navy and the annihilation of almost half of Pakistan's Navy.[56] By the end of the war, the damage inflicted by the Indian Navy and Air Forces on Pakistan's Navy stood at two destroyers, one submarine, one minesweeper, three patrol vessels, seven gunboats, eighteen cargo, supply and communication vessels, as well as large-scale damage inflicted on the naval base and docks located in the major port city of Karachi.[57] Three merchant navy ships, Anwar Baksh, Pasni, and Madhumathi,[58] and ten smaller vessels were captured.[59] Around 1,900 personnel were lost, while 1,413 servicemen (mostly officers) were captured by Indian forces in Dhaka.[60] The Indian Navy lost 18 officers and 194 sailors[citation needed] and a frigate, while another frigate was badly damaged and a Breguet Alizé naval aircraft was shot down by the Pakistan Air Force.[61]

In the 1982 Falklands War between Argentina and the United Kingdom, a Royal Navy task force of approximately 100 ships was dispatched over 7,000 miles (11,000 km) from the British mainland to the South Atlantic. The British were outnumbered in theatre airpower with only 36 Harriers from their two aircraft carriers and a few helicopters, compared with at least 200 aircraft of the Fuerza Aérea Argentina, although London dispatched Vulcan bombers in a display of long-distance strategic capacity. Most of the land-based aircraft of the Royal Air Force were not available due to the distance from air bases. This reliance on aircraft at sea showed the importance of the aircraft carrier. The Falklands War showed the vulnerability of modern ships to sea-skimming missiles like the Exocet. One hit from an Exocet sank HMS Sheffield, a modern anti-air warfare destroyer. Over half of Argentine deaths in the war occurred when the nuclear submarine Conqueror torpedoed and sank the light cruiser ARA General Belgrano with the loss of 323 lives. Important lessons about ship design, damage control and ship construction materials were learnt from the conflict.

-

Aircraft carrier USS Lexington under heavy air attack during the Battle of the Coral Sea, the first carrier-versus-carrier battle in history.

-

Battle of Savo Island was the first in a series of night-time engagements between surface warships during the Solomon Islands campaign.

-

USS Theodore Roosevelt launches an F-14 Tomcat while F/A-18 Hornets wait their turn during the Kosovo War

-

HMAS Sydney in the Persian Gulf (1991)

-

A United States Naval Landing Craft Air Cushion in the Pacific Ocean (2012)

21st century

[edit]At the present time, large naval wars are seldom-seen affairs, since nations with substantial navies rarely fight each other; most wars are civil wars or some form of asymmetrical warfare, fought on land, sometimes with the involvement of military aircraft. The main function of the modern navy is to exploit its control of the seaways to project power ashore. Power projection has been the primary naval feature of most late-century conflicts including the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Persian Gulf War, the War in Afghanistan, and the Iraq War. A major exception to that trend was the Sri Lankan Civil War, which saw a large number of surface engagements between the belligerents involving fast attack craft and other littoral warfare units.[62][63]

The lack of large fleet-on-fleet actions does not, however, mean that naval warfare has ceased to feature in modern conflicts. The bombing of the USS Cole on October 12, 2000, claimed the lives of seventeen sailors, wounded an additional thirty-seven, and cost the Cole fourteen months of repairs.[64][65] Though the attack did not eliminate the United States' control of the local seas, in the short-term, it did prompt the US Navy to reduce its visits to far-flung ports, as military planners struggled to ensure their security.[66] This reduced US Naval presence was ultimately reversed in the wake of the September 11 attacks, as part of the Global War on Terrorism.[67]

Even in the absence of major wars, warships from opposing navies clash periodically at sea, sometimes with fatal results. For example, 46 sailors drowned in the 2010 sinking of the ROKS Cheonan, which South Korea and the United States blamed on a North Korean torpedo attack.[68] North Korea, in turn, denied all responsibility, accused South Korea of violating North Korean territorial waters, and offered to send its own team of investigators to "examine the evidence."[69]

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the armed forces of both Russia and Ukraine have openly targeted and destroyed each other's ships. Though many of these are supporting vessels, such as landing ships, tugs, and patrol boats,[70][71] several larger warships have also been destroyed. Notably, the Ukrainian Navy scuttled its flagship, the frigate Hetman Sahaidachny, to prevent its capture,[72] while the patrol ship Sloviansk was sunken by Russian air attack.[73] The Russian Navy lost the flagship of its Black Sea Fleet, the Moskva, in what the Ukrainian Navy has claimed as a successful Neptune anti-ship missile strike.[74] The Russian Navy, while not admitting to the Ukrainian claims of a missile attack, has confirmed the sinking of the Moskva.[75] As of May 2022, the naval war between Russia and Ukraine is ongoing, as the Russian Navy attempts to dominate Black Sea trade routes, and the Ukrainian Military attempts to erode Russian naval control.[76] Since October 2023 the Red Sea crisis has been ongoing where the Yemeni Houthis have been facing against the US navy , Israel, the UK and a coalition of other nations ,US admiral Brad Cooper said the fight against the Houthis in the Red Sea is the largest battle the US Navy has fought since World War II with about 7,000 sailors committed to the Red Sea.[77][78]

Naval history of nations and empires

[edit]- Genoese Navy

- Hellenic Navy (Greece)

- Roman navy

- Byzantine navy (Eastern Roman Empire)

- Fatimid navy

- Ottoman Navy (Turkey)

- History of the Royal Navy

- History of the French Navy

- History of the Indian Navy

- History of the Iranian Navy

- Naval history of China

- Naval history of Japan

- Naval history of Korea

- Naval history of the Netherlands

- Bangladesh Navy

- Italian Navy

- Spanish Navy

- Pakistan Navy

- Portuguese Navy

- Philippine Navy

- Russian Navy

- History of the United States Navy

- Royal Australian Navy

- Indonesian Navy

- Venetian Navy

- The German navy has operated under different names. See

- Brandenburg Navy, from the 16th century to 1701

- Prussian Navy, 1701–1867

- Reichsflotte (Fleet of the Realm), 1848–52

- North German Federal Navy, 1867–71

- Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial German Navy), 1871–1919

- Reichsmarine (Navy of the Realm), 1919–35

- Kriegsmarine (War Navy), 1935–45

- German Mine Sweeping Administration, 1945 to 1956

- German Navy, since 1956

- Volksmarine, the navy of East Germany, 1956–90

See also

[edit]- Bibliography of early American naval history

- Bibliography of 18th–19th century Royal Naval history

- Command of the sea

- History of ship transport

- Maritime power

- Maritime republics

- Maritime timeline

- Naval history of World War II

- Naval infantry

- Naval strategy

- Naval tactics

- Piracy

- Submarine warfare

- Surface warfare

- Thalassocracy

- War film

- Warship

- Major theorists: Sir Julian Corbett and Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan (The Influence of Sea Power Upon History)

Lists:

- List of naval battles

- List of navies

- Category:Naval historians, list of naval historians

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Warming, Rolf (January 2019). "An Introduction to Hand-to-Hand Combat at Sea: General Characteristics and Shipborne Technologies from c. 1210 BCE to 1600 CE". On War on Board: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on Early Modern Maritime Violence and Warfare (Ed. Johan Rönnby).

- ^ Warming, Rolf (2019). "An Introduction to Hand-to-Hand Combat at Sea: General Characteristics and Shipborne Technologies from c. 1210 BCE to 1600 CE". Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on Early Modern Maritime Violence and Warfare (Ed. Johan Rönnby). Södertörn Högskola: 99–12. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Beckman, Gary (2000). "Hittite Chronology". Akkadica. 119–120: 19–32 [p. 23]. ISSN 1378-5087.

- ^ D.B. Saddington (2011) [2007]. "the Evolution of the Roman Imperial Fleets," in Paul Erdkamp (ed), A Companion to the Roman Army, 201–217. Malden, Oxford, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2153-8. Plate 12.2 on p. 204.

- ^ Coarelli, Filippo (1987), I Santuari del Lazio in età repubblicana. NIS, Rome, pp. 35–84.

- ^ "Ancient Discoveries, Episode 12: Machines of the East". History Channel. Archived from the original on 2010-12-25. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jean-Claude Castex, [1] Dictionnaire des batailles navales franco-anglaises, Presses de l'Université Laval, 2004, p. 21

- ^ Shen, 155

- ^ Christie, Anthony (1957). "An Obscure Passage from the "Periplus: ΚΟΛΑΝΔΙΟϕΩΝΤΑ ΤΑ ΜΕΓΙΣΤΑ"". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 19: 345–353. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00133105. S2CID 162840685.

- ^ Dick-Read, Robert (2005). The Phantom Voyagers: Evidence of Indonesian Settlement in Africa in Ancient Times. Thurlton.

- ^ Nik Hassan Shuhaimi Nik Abd Rahman. "Port and polity of the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra (5th – 14th Centuries A.D.)" (PDF). International Seminar Harbour Cities Along the Silk Roads.

- ^ a b Kumar, Ann (2012). 'Dominion Over Palm and Pine: Early Indonesia's Maritime Reach', in Geoff Wade (ed.), Anthony Reid and the Study of the Southeast Asian Past (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies), 101–122.

- ^ Lombard, Denys (2005). Nusa Jawa: Silang Budaya, Bagian 2: Jaringan Asia. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. An Indonesian translation of Lombard, Denys (1990). Le carrefour javanais. Essai d'histoire globale (The Javanese Crossroads: Towards a Global History) vol. 2. Paris: Éditions de l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.

- ^ a b Nugroho, Irawan Djoko (2011). Majapahit Peradaban Maritim. Suluh Nuswantara Bakti. ISBN 9786029346008.

- ^ Munoz, Paul Michel (2006). Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. p. 171. ISBN 981-4155-67-5.

- ^ Nugroho, Irawan Djoko (2009). Meluruskan Sejarah Majapahit. Ragam Media. ISBN 978-9793840161.

- ^ da Pordenone, Odoric (2002). The Travels of Friar Odoric. W. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802849632.: 106–107

- ^ "Ibn Battuta's Trip: Chapter 9 Through the Straits of Malacca to China 1345–1346". The Travels of Ibn Battuta A Virtual Tour with the 14th Century Traveler. Berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ a b Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1976). "L'Artillerie legere nousantarienne: A propos de six canons conserves dans des collections portugaises" (PDF). Arts Asiatiques. 32: 233–268. doi:10.3406/arasi.1976.1103. S2CID 191565174.

- ^ Averoes, Muhammad (2020). Antara Cerita dan Sejarah: Meriam Cetbang Majapahit. Jurnal Sejarah, 3(2), 89–100.

- ^ Averoes, Muhammad (2022). "Re-Estimating the Size of Javanese Jong Ship". Historia: Jurnal Pendidik Dan Peneliti Sejarah. 5 (1): 57–64. doi:10.17509/historia.v5i1.39181. S2CID 247335671.

- ^ Hill (June 1960). "Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 33: pp. 98, 157: "Then he directed them to make ready all the equipment and munitions of war needed for an attack on the land of Pasai – about four hundred of the largest junks, and also many barges (malangbang) and galleys." See also Nugroho (2011). pp. 270, 286, quoting Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai, 3: 98: "Sa-telah itu, maka di-suroh baginda musta'idkan segala kelengkapan dan segala alat senjata peperangan akan mendatangi negeri Pasai itu, sa-kira-kira empat ratus jong yang besar-besar dan lain daripada itu banyak lagi daripada malangbang dan kelulus." (After that, he is tasked by His Majesty to ready all the equipment and all weapons of war to come to that country of Pasai, about four hundred large jongs and other than that much more of malangbang and kelulus.)

- ^ Wade, Geoff (2012). Anthony Reid and the Study of the Southeast Asian Past. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4311-96-0.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1971). Science and Civilisation in China: Civil Engineering and Nautics, Volume 4 Part 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-521-07060-7.

- ^ Franke, Herbert (1994). Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 241–242. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- ^ a b Lo, Jung-pang (2012). China as Sea Power 1127–1368. Singapore: NUS Press.

- ^ Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. China Branch (1895). Journal of the China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society for the year ..., Volumes 27–28. Shanghai: The Branch. p. 44. Retrieved 28 June 2010. (Original from Princeton University)

- ^ Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. North-China Branch (1894). Journal of the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volumes 26–27. Shanghai: The Branch. p. 44. Retrieved 28 June 2010.(Original from Harvard University)

- ^ Donald F. Lach, Edwin J. Van Kley (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe: A Century of Advance: East Asia. University of Chicago Press. p. 752. ISBN 0-226-46769-4. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Andrade, Tonio. "11: The Fall of Dutch Taiwan". How Taiwan Became Chinese Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century. Columbia University Press. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Lynn A. Struve (1998). Voices from the Ming-Qing cataclysm: China in tigers' jaws. Yale University Press. p. 312. ISBN 0-300-07553-7. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Perez, Louis (2013). Japan at war: an encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-59884-742-0. OCLC 827944888.

- ^ Swope, Kenneth (2013). A dragon's head and a serpent's tail: Ming China and the first great East Asian war, 1592–1598. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 115–119. ISBN 978-0-8061-8502-6. OCLC 843883049.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2012). The Samurai Invasion of Korea 1592–98. Dennis, Peter. Oxford: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 36–43. ISBN 978-1-84603-758-0. OCLC 437089282.

- ^ Strauss, Barry (Summer 2005). "Korea's Legendary Admiral". The Quarterly Journal of Military History. 17 (4): 52–61.

- ^ Swope, Kenneth (2013). A dragon's head and a serpent's tail: Ming China and the first great East Asian war, 1592–1598. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8061-8502-6. OCLC 843883049.

- ^ Yi, Min'ung; Lewis, James Bryant (2014). The East Asian War, 1592–1598: international relations, violence and memory. London: Routledge. pp. 130–132. ISBN 978-1-317-66274-7. OCLC 897810515.

- ^ Yi, Min'ung; Lewis, James Bryant (2014). The East Asian War, 1592–1598: international relations, violence and memory. London: Routledge. pp. 132–134. ISBN 978-1-317-66274-7. OCLC 897810515.

- ^ History of Ming Vol. 247 [2]

- ^ [3] Japan Encyclopedia, By Louis Frédéric (p. 92)

- ^ Swope, Kenneth (2013). A dragon's head and a serpent's tail: Ming China and the first great East Asian war, 1592–1598. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 271–276. ISBN 978-0-8061-8502-6. OCLC 843883049.

- ^ Perez, Louis G (2013). Japan at war: an encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-1-59884-742-0. OCLC 827944888.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, p. 678

- ^ "When Europeans were slaves: Research suggests white slavery was much more common than previously believed". Archived from the original on 2011-07-25.

- ^ Davis, Robert. Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500–1800.[4]

- ^ Simon de Bruxelles (28 February 2007). "Pirates who got away with it by sailing closer to the wind". The Times. Archived from the original on March 2, 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ Charles Ralph Boxer: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th Century, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1974.

- ^ N.A.M. Rodger: The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649—1815, New York, 2004 ISBN 0-393-32847-3

- ^ Tagaya (2001) "Mitsubishi Type 1 Rikko 'Betty' Units of World War 2"

- ^ a b Lundstrom (2005a) "The First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway"

- ^ a b Lundstrom (2005b) "First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign: Naval Fighter Combat from August to November 1942"

- ^ Morison (1958) "The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942 – February 1943"

- ^ Morison (1956) "Leyte, June 1944 – January 1945"

- ^ Work, Robert O. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Winning the Race: A Naval Fleet Platform Architecture for Enduring Maritime Supremacy Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments Online. Retrieved 8 April 2006 - ^ Tariq Ali (1983). Can Pakistan Survive? The Death of a State. United Kingdom: Penguin Books. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-14-02-2401-6.

In a two-week war, Pakistan lost half its navy.

- ^ Tiwana, M.A. Hussain (November 1998). "The Angry Sea". www.defencejournal.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ "Chapter-39". Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ^ "Damage Assessment – 1971 Indo-Pak Naval War" (PDF). B. Harry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2005. Retrieved 16 May 2005.

- ^ "Military Losses in the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War". Venik. Archived from the original on 25 February 2002. Retrieved 30 May 2005.

- ^ Tiwana, M.A. Hussain (November 1998). "The Angry Sea". www.defencejournal.com. M.A. Hussain Tiwana Defence Journal. Archived from the original on 13 March 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ "A Guerilla War at Sea: The Sri Lankan Civil War | Small Wars Journal". 9 September 2011.

- ^ "21st Century Seapower, Inc". 2015-12-31.

- ^ "USS Cole (DDG-67), Determined Warrior". Archived from the original on 31 May 2019.

- ^ "USS 'Cole' Returns to U.S. Navy Fleet Following Restoration by Northrop Grumman".

- ^ "Lessons Learned from the Attack on the U.S.S. 'Cole'".

- ^ "A reckoning is near". USA Today. 25 February 2021.

- ^ "South Korea: Torpedo probably sank warship". NBC News. 25 April 2010.

- ^ "North Korea rebuffs South Korea's evidence on 'Cheonan' attack". Christian Science Monitor. 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Russia shows off captured navy boats". BBC News.

- ^ "Ukrainian drone destroys Russian patrol ships off Snake Island". CNN. 2 May 2022.

- ^ "The Fate of Ukraine's Flagship Frigate". 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine Reports Loss of U.S.-Built Patrol Boat by Russian Missile".

- ^ "Russian warship: 'Moskva' sinks in Black Sea". Archived from the original on 15 April 2022.

- ^ "Factbox: The 'Moskva', Russia's lost Black Sea Fleet flagship". Reuters. 14 April 2022.

- ^ "The Russo-Ukrainian War At Sea: Retrospect And Prospect". 21 April 2022.

- ^ https://www.livenowfox.com/news/navy-red-sea-combat

- ^ https://www.businessinsider.com/red-sea-conflict-largest-navy-battle-since-world-war-ii-2024-2

Sources

[edit]- Shen, Fuwei (1996). Cultural Flow Between China and the Outside World. China Books & Periodicals. ISBN 978-7-119-00431-0

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China. Volume 4, Part 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

Further reading

[edit]- Holmes, Richard, et al., eds. The Oxford companion to military history (Oxford University Press, 2001), global.

- Howarth, David British Sea Power: How Britain Became Sovereign of the Seas (2003), 320 pp. from 1066 to present

- Padfield, Peter. Maritime Dominion and the Triumph of the Free World: Naval Campaigns That Shaped the Modern World 1852–2001 (2009)

- Potter, E. B. Sea Power: A Naval History (1982), world history

- Rodger, Nicholas A.M. The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649–1815. Vol. 2. (WW Norton & Company, 2005).

- Rönnby, J. 2019. "On War On Board: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on Early Modern Maritime Violence and Warfare". Södertörn Archaeological Studies 15. Södertörn Högskola.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence. Naval Warfare, 1815–1914 (2001).

- Starr, Chester. The Influence of Sea Power on Ancient History (1989)

- Tucker, Spencer, ed. Naval Warfare: An International Encyclopedia (3 vol. Cambridge UP, 2002); 1231 pp; 1500 articles by many experts cover 2500 years of world naval history, esp. battles, commanders, technology, strategies and tactics,

- Tucker, Spencer. Handbook of 19th century naval warfare (Naval Inst Press, 2000).

- Willmott, H. P. The Last Century of Sea Power, Volume 1: From Port Arthur to Chanak, 1894–1922 (2009), 568 pp. online in ebrary

- Willmott, H. P. The Last Century of Sea Power, vol. 2: From Washington to Tokyo, 1922–1945. (Indiana University Press, 2010). xxii, 679 pp. ISBN 978-0-253-35359-7 online in ebrary

Warships

[edit]- George, James L. History of warships: From ancient times to the twenty-first century (Naval Inst Press, 1998).

- Ireland, Bernard, and Eric Grove. Jane's War at Sea 1897–1997: 100 Years of Jane's Fighting Ships (1997) covers all important ships of all major countries.

- Peebles, Hugh B. Warshipbuilding on the Clyde: Naval orders and the prosperity of the Clyde shipbuilding industry, 1889–1939 (John Donald, 1987)

- Van der Vat, Dan. Stealth at sea: the history of the submarine (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995).

Sailors and officers

[edit]- Conley, Mary A. From Jack Tar to Union Jack: representing naval manhood in the British Empire, 1870–1918 (Manchester UP, 2009)

- Hubbard, Eleanor. "Sailors and the Early Modern British Empire: Labor, Nation, and Identity at Sea." History Compass 14.8 (2016): 348–358.

- Kemp, Peter. The British Sailor: a social history of the lower deck (1970)

- Langley, Harold D. "Union Jacks: Yankee Sailors in the Civil War." Journal of Military History 69.1 (2005): 239.

- Ortega-del-Cerro, Pablo, and Juan Hernández-Franco. "Towards a definition of naval elites: reconsidering social change in Britain, France and Spain, c. 1670–1810." European Review of History: Revue européenne d'histoire (2017): 1–22.

- Smith, Simon Mark. "'We Sail the Ocean Blue': British sailors, imperialism, identity, pride and patriotism c. 1890 to 1939" (PhD dissertatation U of Portsmouth, 2017. online

First World War

[edit]- Bennett, Geoffrey. Naval Battles of the First World War (Pen and Sword, 2014)

- Halpern, Paul. A naval history of World War I (Naval Institute Press, 2012).

- Hough, Richard. The Great War at Sea, 1914–1918 (Oxford UP, 1987)

- Marder, Arthur Jacob. From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow (4 vol. 1961–70), covers Britain's Royal Navy 1904–1919

- O'Hara, Vincent P.; Dickson, W. David; Worth, Richard, eds. To Crown the Waves: The Great Navies of the First World War (2013) excerpt also see detailed review and summary of world's navie before and during the war

- Sondhaus, Lawrence The Great War at Sea: A Naval History of the First World War (2014). online review

Second World War

[edit]- Barnett, Correlli. Engage the Enemy More Closely: The Royal Navy in the Second World War (1991).

- Campbell, John. Naval Weapons of World War Two (Naval Institute Press, 1985).

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War (1963) short version of his 13 volume history.

- O'Hara, Vincent. The German Fleet at War, 1939–1945 (Naval Institute Press, 2013).

- Roskill, S.K. White Ensign: The British Navy at War, 1939–1945 (United States Naval Institute, 1960); British Royal Navy; abridged version of his Roskill, Stephen Wentworth. The war at sea, 1939–1945 (3 vol. 1960).

- Van der Vat, Dan. The Pacific Campaign: The Second World War, the US-Japanese Naval War (1941–1945) (2001).

Historiography

[edit]- Harding, Richard ed., Modern Naval History: Debates and Prospects (London: Bloomsbury, 2015)

- Higham, John, ed. A Guide to the Sources of British Military History (2015) 654 pp. excerpt

- Messenger, Charles. Reader's Guide to Military History (Routledge, 2013) comprehensive guide to historical books on global military & naval history.

- Zurndorfer, Harriet. "Oceans of history, seas of change: recent revisionist writing in western languages about China and East Asian maritime history during the period 1500–1630." International Journal of Asian Studies 13.1 (2016): 61–94.