Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

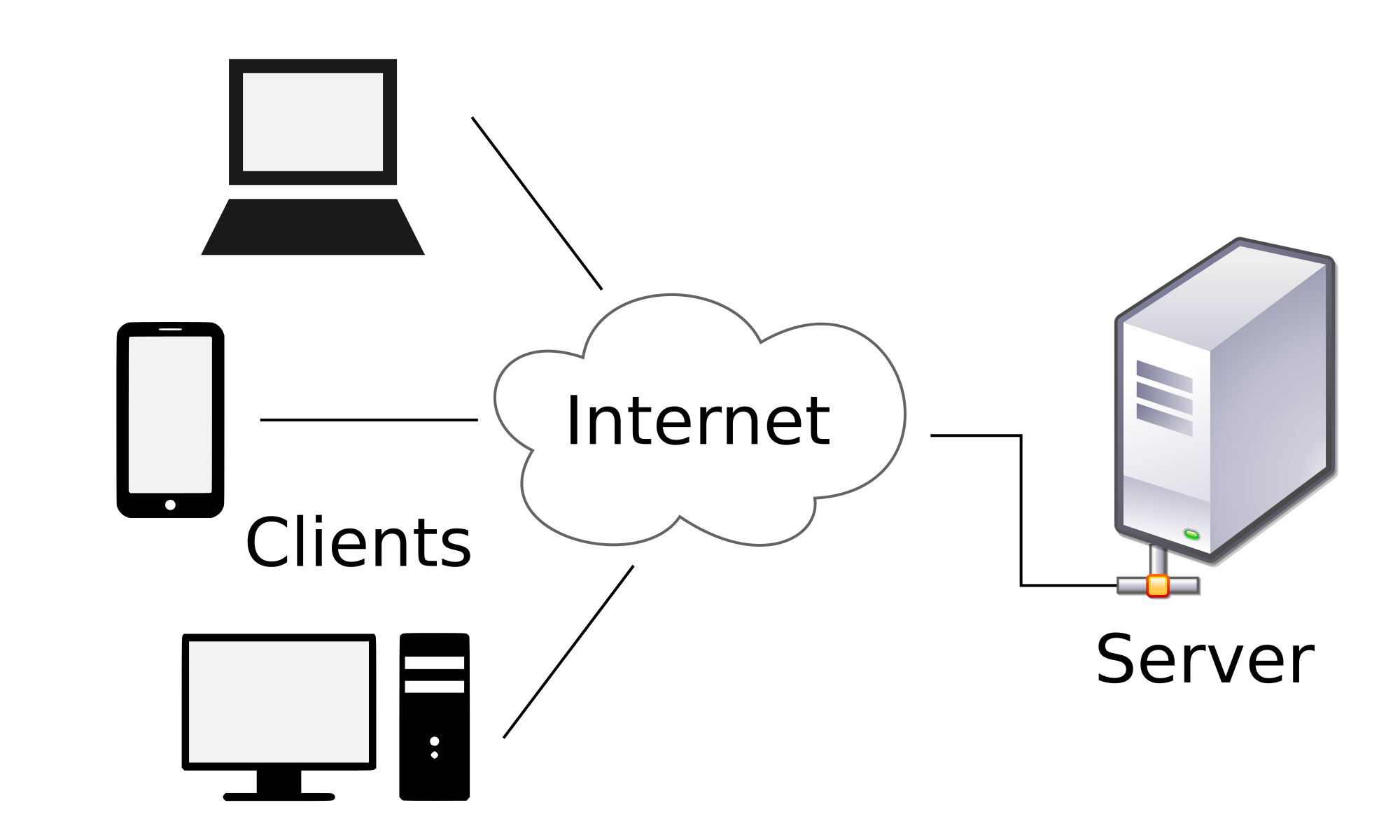

Client–server model

View on WikipediaThis article (some sections) needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

The client–server model is a distributed application structure that partitions tasks or workloads between the providers of a resource or service, called servers, and service requesters, called clients.[1] Often clients and servers communicate over a computer network on separate hardware, but both client and server may be on the same device. A server host runs one or more server programs, which share their resources with clients. A client usually does not share its computing resources, but it requests content or service from a server and may share its own content as part of the request. Clients, therefore, initiate communication sessions with servers, which await incoming requests. Examples of computer applications that use the client–server model are email, network printing, and the World Wide Web.

Client and server role

[edit]The server component provides a function or service to one or many clients, which initiate requests for such services. Servers are classified by the services they provide. For example, a web server serves web pages and a file server serves computer files. A shared resource may be any of the server computer's software and electronic components, from programs and data to processors and storage devices. The sharing of resources of a server constitutes a service.

Whether a computer is a client, a server, or both, is determined by the nature of the application that requires the service functions. For example, a single computer can run a web server and file server software at the same time to serve different data to clients making different kinds of requests. The client software can also communicate with server software within the same computer.[2] Communication between servers, such as to synchronize data, is sometimes called inter-server or server-to-server communication.

Client and server communication

[edit]Generally, a service is an abstraction of computer resources and a client does not have to be concerned with how the server performs while fulfilling the request and delivering the response. The client only has to understand the response based on the relevant application protocol, i.e. the content and the formatting of the data for the requested service.

Clients and servers exchange messages in a request–response messaging pattern. The client sends a request, and the server returns a response. This exchange of messages is an example of inter-process communication. To communicate, the computers must have a common language, and they must follow rules so that both the client and the server know what to expect. The language and rules of communication are defined in a communications protocol. All protocols operate in the application layer. The application layer protocol defines the basic patterns of the dialogue. To formalize the data exchange even further, the server may implement an application programming interface (API).[3] The API is an abstraction layer for accessing a service. By restricting communication to a specific content format, it facilitates parsing. By abstracting access, it facilitates cross-platform data exchange.[4]

A server may receive requests from many distinct clients in a short period. A computer can only perform a limited number of tasks at any moment, and relies on a scheduling system to prioritize incoming requests from clients to accommodate them. To prevent abuse and maximize availability, the server software may limit the availability to clients. Denial of service attacks are designed to exploit a server's obligation to process requests by overloading it with excessive request rates. Encryption should be applied if sensitive information is to be communicated between the client and the server.

Example

[edit]When a bank customer accesses online banking services with a web browser (the client), the client initiates a request to the bank's web server. The customer's login credentials are compared against a database, and the webserver accesses that database server as a client. An application server interprets the returned data by applying the bank's business logic and provides the output to the webserver. Finally, the webserver returns the result to the client web browser for display.

In each step of this sequence of client–server message exchanges, a computer processes a request and returns data. This is the request-response messaging pattern. When all the requests are met, the sequence is complete.

This example illustrates a design pattern applicable to the client–server model: separation of concerns.

Server-side

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2016) |

Server-side refers to programs and operations that run on the server. This is in contrast to client-side programs and operations which run on the client.

General concepts

[edit]"Server-side software" refers to a computer application, such as a web server, that runs on remote server hardware, reachable from a user's local computer, smartphone, or other device.[5] Operations may be performed server-side because they require access to information or functionality that is not available on the client, or because performing such operations on the client side would be slow, unreliable, or insecure.

Client and server programs may be commonly available ones such as free or commercial web servers and web browsers, communicating with each other using standardized protocols. Or, programmers may write their own server, client, and communications protocol which can only be used with one another.

Server-side operations include both those that are carried out in response to client requests, and non-client-oriented operations such as maintenance tasks.[6][7]

Computer security

[edit]In a computer security context, server-side vulnerabilities or attacks refer to those that occur on a server computer system, rather than on the client side, or in between the two. For example, an attacker might exploit an SQL injection vulnerability in a web application in order to maliciously change or gain unauthorized access to data in the server's database. Alternatively, an attacker might break into a server system using vulnerabilities in the underlying operating system and then be able to access database and other files in the same manner as authorized administrators of the server.[8][9][10]

Examples

[edit]In the case of distributed computing projects such as SETI@home and the Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search, while the bulk of the operations occur on the client side, the servers are responsible for coordinating the clients, sending them data to analyze, receiving and storing results, providing reporting functionality to project administrators, etc. In the case of an Internet-dependent user application like Google Earth, while querying and display of map data takes place on the client side, the server is responsible for permanent storage of map data, resolving user queries into map data to be returned to the client, etc.

Web applications and services can be implemented in almost any language, as long as they can return data to standards-based web browsers (possibly via intermediary programs) in formats which they can use.

Client side

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2016) |

Client-side refers to operations that are performed by the client in a computer network.

General concepts

[edit]Typically, a client is a computer application, such as a web browser, that runs on a user's local computer, smartphone, or other device, and connects to a server as necessary. Operations may be performed client-side because they require access to information or functionality that is available on the client but not on the server, because the user needs to observe the operations or provide input, or because the server lacks the processing power to perform the operations in a timely manner for all of the clients it serves. Additionally, if operations can be performed by the client, without sending data over the network, they may take less time, use less bandwidth, and incur a lesser security risk.

When the server serves data in a commonly used manner, for example according to standard protocols such as HTTP or FTP, users may have their choice of a number of client programs (e.g. most modern web browsers can request and receive data using both HTTP and FTP). In the case of more specialized applications, programmers may write their own server, client, and communications protocol which can only be used with one another.

Programs that run on a user's local computer without ever sending or receiving data over a network are not considered clients, and so the operations of such programs would not be termed client-side operations.

Computer security

[edit]In a computer security context, client-side vulnerabilities or attacks refer to those that occur on the client / user's computer system, rather than on the server side, or in between the two. As an example, if a server contained an encrypted file or message which could only be decrypted using a key housed on the user's computer system, a client-side attack would normally be an attacker's only opportunity to gain access to the decrypted contents. For instance, the attacker might cause malware to be installed on the client system, allowing the attacker to view the user's screen, record the user's keystrokes, and steal copies of the user's encryption keys, etc. Alternatively, an attacker might employ cross-site scripting vulnerabilities to execute malicious code on the client's system without needing to install any permanently resident malware.[8][9][10]

Examples

[edit]Distributed computing projects such as SETI@home and the Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search, as well as Internet-dependent applications like Google Earth, rely primarily on client-side operations. They initiate a connection with the server (either in response to a user query, as with Google Earth, or in an automated fashion, as with SETI@home), and request some data. The server selects a data set (a server-side operation) and sends it back to the client. The client then analyzes the data (a client-side operation), and, when the analysis is complete, displays it to the user (as with Google Earth) and/or transmits the results of calculations back to the server (as with SETI@home).

Early history

[edit]An early form of client–server architecture is remote job entry, dating at least to OS/360 (announced 1964), where the request was to run a job, and the response was the output.

While formulating the client–server model in the 1960s and 1970s, computer scientists building ARPANET (at the Stanford Research Institute) used the terms server-host (or serving host) and user-host (or using-host), and these appear in the early documents RFC 5[11] and RFC 4.[12] This usage was continued at Xerox PARC in the mid-1970s.

One context in which researchers used these terms was in the design of a computer network programming language called Decode-Encode Language (DEL).[11] The purpose of this language was to accept commands from one computer (the user-host), which would return status reports to the user as it encoded the commands in network packets. Another DEL-capable computer, the server-host, received the packets, decoded them, and returned formatted data to the user-host. A DEL program on the user-host received the results to present to the user. This is a client–server transaction. Development of DEL was just beginning in 1969, the year that the United States Department of Defense established ARPANET (predecessor of Internet).

Client-host and server-host

[edit]Client-host and server-host have subtly different meanings than client and server. A host is any computer connected to a network. Whereas the words server and client may refer either to a computer or to a computer program, server-host and client-host always refer to computers. The host is a versatile, multifunction computer; clients and servers are just programs that run on a host. In the client–server model, a server is more likely to be devoted to the task of serving.

An early use of the word client occurs in "Separating Data from Function in a Distributed File System", a 1978 paper by Xerox PARC computer scientists Howard Sturgis, James Mitchell, and Jay Israel. The authors are careful to define the term for readers, and explain that they use it to distinguish between the user and the user's network node (the client).[13] By 1992, the word server had entered into general parlance.[14][15]

Centralized computing

[edit]The client-server model does not dictate that server-hosts must have more resources than client-hosts. Rather, it enables any general-purpose computer to extend its capabilities by using the shared resources of other hosts. Centralized computing, however, specifically allocates a large number of resources to a small number of computers. The more computation is offloaded from client-hosts to the central computers, the simpler the client-hosts can be.[16] It relies heavily on network resources (servers and infrastructure) for computation and storage. A diskless node loads even its operating system from the network, and a computer terminal has no operating system at all; it is only an input/output interface to the server. In contrast, a rich client, such as a personal computer, has many resources and does not rely on a server for essential functions.

As microcomputers decreased in price and increased in power from the 1980s to the late 1990s, many organizations transitioned computation from centralized servers, such as mainframes and minicomputers, to rich clients.[17] This afforded greater, more individualized dominion over computer resources, but complicated information technology management.[16][18][19] During the 2000s, web applications matured enough to rival application software developed for a specific microarchitecture. This maturation, more affordable mass storage, and the advent of service-oriented architecture were among the factors that gave rise to the cloud computing trend of the 2010s.[20][failed verification]

Comparison with peer-to-peer architecture

[edit]In addition to the client-server model, distributed computing applications often use the peer-to-peer (P2P) application architecture.

In the client-server model, the server is often designed to operate as a centralized system that serves many clients. The computing power, memory and storage requirements of a server must be scaled appropriately to the expected workload. Load-balancing and failover systems are often employed to scale the server beyond a single physical machine.[21][22]

Load balancing is defined as the methodical and efficient distribution of network or application traffic across multiple servers in a server farm. Each load balancer sits between client devices and backend servers, receiving and then distributing incoming requests to any available server capable of fulfilling them.

In a peer-to-peer network, two or more computers (peers) pool their resources and communicate in a decentralized system. Peers are coequal, or equipotent nodes in a non-hierarchical network. Unlike clients in a client-server or client-queue-client network, peers communicate with each other directly.[23] In peer-to-peer networking, an algorithm in the peer-to-peer communications protocol balances load, and even peers with modest resources can help to share the load.[24] If a node becomes unavailable, its shared resources remain available as long as other peers offer it. Ideally, a peer does not need to achieve high availability because other, redundant peers make up for any resource downtime; as the availability and load capacity of peers change, the protocol reroutes requests.

Both client-server and master-slave are regarded as sub-categories of distributed peer-to-peer systems.[25]

See also

[edit]- Endpoint security

- Front and back ends

- Modular programming

- Observer pattern

- Publish–subscribe pattern

- Pull technology

- Push technology

- Remote procedure call

- Server change number

- Systems Network Architecture, a proprietary network architecture by IBM

- Thin client

- Configurable Network Computing, a proprietary client-server architecture by JD Edwards

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Distributed Application Architecture" (PDF). Sun Microsystem. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2011. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ The X Window System is one example.

- ^ Benatallah, B.; Casati, F.; Toumani, F. (2004). "Web service conversation modeling: A cornerstone for e-business automation". IEEE Internet Computing. 8: 46–54. doi:10.1109/MIC.2004.1260703. S2CID 8121624.

- ^ Dustdar, S.; Schreiner, W. (2005). "A survey on web services composition" (PDF). International Journal of Web and Grid Services. 1: 1. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.139.4827. doi:10.1504/IJWGS.2005.007545.

- ^ "What do client side and server side mean? Client side vs. server side". Cloudflare. Retrieved 17 April 2025.

- ^ "Introduction to the server side - Learn web development | MDN". developer.mozilla.org. 2023-11-05. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ "Server-side website programming - Learn web development | MDN". developer.mozilla.org. 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ a b Lehtinen, Rick; Russell, Deborah; Gangemi, G. T. (2006). Computer Security Basics (2nd ed.). O'Reilly Media. ISBN 9780596006693. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- ^ a b JS (2015-10-15). "Week 4: Is There a Difference between Client Side and Server Side?". n3tweb.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- ^ a b Espinosa, Christian (2016-04-23). "Decoding the Hack" (PDF). alpinesecurity.com. Retrieved 2017-07-07.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Rulifson, Jeff (June 1969). DEL. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC0005. RFC 5. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ Shapiro, Elmer B. (March 1969). Network Timetable. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC0004. RFC 4. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ Sturgis, Howard E.; Mitchell, James George; Israel, Jay E. (1978). "Separating Data from Function in a Distributed File System". Xerox PARC.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "server". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ "Separating data from function in a distributed file system". GetInfo. German National Library of Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ^ a b Nieh, Jason; Yang, S. Jae; Novik, Naomi (2000). "A Comparison of Thin-Client Computing Architectures". Academic Commons. doi:10.7916/D8Z329VF. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ d'Amore, M. J.; Oberst, D. J. (1983). "Microcomputers and mainframes". Proceedings of the 11th annual ACM SIGUCCS conference on User services - SIGUCCS '83. p. 7. doi:10.1145/800041.801417. ISBN 978-0897911160. S2CID 14248076.

- ^ Tolia, Niraj; Andersen, David G.; Satyanarayanan, M. (March 2006). "Quantifying Interactive User Experience on Thin Clients" (PDF). Computer. 39 (3). IEEE Computer Society: 46–52. doi:10.1109/mc.2006.101. S2CID 8399655.

- ^ Otey, Michael (22 March 2011). "Is the Cloud Really Just the Return of Mainframe Computing?". SQL Server Pro. Penton Media. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Barros, A. P.; Dumas, M. (2006). "The Rise of Web Service Ecosystems". IT Professional. 8 (5): 31. doi:10.1109/MITP.2006.123. S2CID 206469224.

- ^ Cardellini, V.; Colajanni, M.; Yu, P.S. (1999). "Dynamic load balancing on Web-server systems". IEEE Internet Computing. 3 (3). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): 28–39. doi:10.1109/4236.769420. ISSN 1089-7801.

- ^ "What Is Load Balancing? How Load Balancers Work". NGINX. June 1, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Alharbi, A.; Aljaedi, A. (2004). "Peer-to-Peer Network Security Issues and Analysis: Review". IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-45172-3_6.

- ^ Rao, A.; Lakshminarayanan, K.; Surana, S.; Manning Karp, R. (2020). "Load Balancing in Structured P2P Systems". IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security. 20: 74–88.

- ^

Varma, Vasudeva (2009). "1: Software Architecture Primer". Software Architecture: A Case Based Approach. Delhi: Pearson Education India. p. 29. ISBN 9788131707494. Retrieved 2017-07-04.

Distributed Peer-to-Peer Systems [...] This is a generic style of which popular styles are the client-server and master-slave styles.

Client–server model

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

The client–server model is a distributed application architecture that divides tasks between service providers, known as servers, and service requesters, known as clients, where clients initiate communication by sending requests and servers respond accordingly.[6][7] This model operates over a computer network, enabling the separation of application logic into distinct components that interact via standardized messages.[7] At its core, the model adheres to the principle of separation of concerns, whereby clients primarily handle user interface presentation and input processing, while servers manage data storage, business logic, and resource access.[8] This division promotes modularity by isolating responsibilities, simplifying development and maintenance compared to integrated systems.[9] Scalability is another foundational principle, as a single server can support multiple clients simultaneously, allowing the system to handle increased demand by adding clients without altering the server or by distributing servers across networks.[10] Interactions may be stateless, where each request is independent and the server retains no client-specific information between calls, or stateful, where the server maintains session data to track ongoing client states.[11] Unlike monolithic applications, which execute all components within a single process or machine without network distribution, the client–server model emphasizes modularity and geographic separation of components over a network, facilitating easier updates and resource sharing.[12] A basic conceptual flow of the model can be illustrated as follows:Client Network Server

| | |

|--- Request ------------>| |

| |--- Process Request ---->|

| |<-- Generate Response ---|

|<-- Response -----------| |

| | |

Client Network Server

| | |

|--- Request ------------>| |

| |--- Process Request ---->|

| |<-- Generate Response ---|

|<-- Response -----------| |

| | |

Advantages and Limitations

The client–server model offers centralized data management, where resources and data are stored on a dedicated server, enabling easier maintenance, backups, and recovery while ensuring consistency across multiple clients. This centralization simplifies administration, as files and access rights are controlled from a single point, reducing the need for distributed updates on individual client devices.[14][15] Resource sharing is another key benefit, allowing multiple clients to access shared hardware, software, and data remotely from various platforms without duplicating resources on each device.[14][16] Scalability is facilitated by the model's design, where server upgrades or additions can handle increased loads without altering client-side configurations, supporting growth in user numbers through load balancing and resource expansion. For instance, servers can be enhanced to manage hundreds or thousands of concurrent connections, depending on hardware capacity, making it suitable for expanding networks.[15][16] Client updates are streamlined since core logic and data processing occur server-side, minimizing the distribution of software changes to endpoints and leveraging the separation of client and server roles for efficient deployment.[14] Despite these strengths, the model has notable limitations, primarily as a single point of failure where server downtime halts access for all clients, lacking the inherent fault tolerance of distributed systems. Network dependency introduces latency and potential congestion, as all communications rely on stable connections, leading to delays or disruptions during high traffic.[14][16] Initial setup costs are higher due to the need for robust server infrastructure, specialized hardware, and professional IT expertise for ongoing management, which can strain smaller organizations.[14][15] In high-traffic scenarios, bottlenecks emerge when server capacity is exceeded, potentially causing performance degradation without additional scaling measures.[15] The client–server model involves trade-offs between centralization, which provides strong control and simplified oversight, and distribution, which offers better fault tolerance but increases complexity in management. While centralization enhances efficiency for controlled environments, it can amplify risks in failure-prone networks, requiring careful assessment of reliability needs against administrative benefits.[15][16]Components

Client Role and Functions

In the client–server model, the client serves as the initiator of interactions, responsible for facilitating user engagement by presenting interfaces and managing local operations while delegating resource-intensive tasks to the server.[17] The client typically operates on the user's device, such as a personal computer or mobile device, and focuses on user-centric activities rather than centralized data processing.[7] Key functions of the client include presenting the user interface (UI), which involves rendering visual elements like forms, menus, and displays to enable intuitive interaction. It collects user inputs, such as form data or search queries, and performs initial validation to ensure completeness and format compliance before transmission, reducing unnecessary server load. The client then initiates requests to the server by establishing a connection, often using sockets to send formatted messages containing the user's intent.[18] Upon receiving responses from the server, the client processes the data—such as parsing structured content—and displays it appropriately, updating the UI in real-time for seamless user experience.[17] Clients vary in design, categorized primarily as thin or fat (also known as thick) based on their processing capabilities. Thin clients perform minimal local computation, handling only UI presentation and basic input/output while relying heavily on the server for application logic and data management; examples include web browsers accessing remote services.[19] In contrast, fat clients incorporate more local processing, such as caching data or executing application logic offline, which enhances responsiveness but increases demands on the client device; desktop applications like email clients with local storage exemplify this type.[19] The client lifecycle begins with initialization, where it creates necessary resources like sockets for network connectivity and loads the UI components.[18] During operation, it manages sessions to maintain state across interactions, often using mechanisms like cookies to track user context without persistent connections. Error handling involves detecting failures in requests, such as connection timeouts or invalid responses, and responding with user-friendly messages or retry attempts to ensure reliability.[18] The lifecycle concludes with cleanup, closing connections and releasing resources once interactions end.[18] Clients are designed to be lightweight in resource usage, leveraging local hardware primarily for UI rendering and input handling while offloading computationally heavy tasks, like data processing or storage, to the server to optimize efficiency across diverse devices.[19] This approach allows clients to run intermittently, activating only when user input requires server interaction, thereby conserving system resources.[18]Server Role and Functions

In the client–server model, the server serves as the centralized backend component responsible for delivering services and resources to multiple clients over a network, operating passively by responding to incoming requests rather than initiating interactions. This role emphasizes resource sharing and centralized control, allowing one server to support numerous clients simultaneously while maintaining data integrity and processing efficiency.[20] The primary functions of a server include listening for client requests, authenticating and authorizing access, processing business logic and retrieving data, and generating appropriate responses. Upon receiving a request, the server first listens on a well-known port to detect incoming connections, using mechanisms like socket creation and binding to prepare for communication.[18] Authentication and authorization verify the client's identity and permissions, ensuring only valid requests proceed, though specific mechanisms vary by implementation.[21] Processing involves executing application logic, querying databases or storage systems for data, and performing computations as needed, such as filtering or transforming information based on the request parameters.[1] Finally, the server constructs and transmits a response, which may include data, status codes, or error messages, completing the interaction cycle.[18] Servers can be specialized by function, such as web servers handling HTTP requests or database servers managing data storage and queries, allowing optimization for specific tasks.[22] Client-server systems may also employ multi-tier architectures, which distribute functions across multiple layers or servers, such as a two-tier setup with a client directly connected to a database server, or more complex n-tier configurations that include application servers and middleware for enhanced scalability and separation of concerns.[20] The server lifecycle encompasses startup, ongoing operation, and shutdown to ensure reliable service delivery. During startup, the server initializes by creating a socket, binding it to a specific IP address and port, and entering a listening state to accept connections, often using iterative or concurrent models to prepare for traffic.[18] In operation, it manages concurrent connections by spawning child processes or threads for each client—such as using ephemeral ports in TCP-based systems—to handle multiple requests without blocking, enabling efficient multitasking.[18] Shutdown involves gracefully closing active sockets, releasing resources, and logging final states to facilitate orderly termination and diagnostics.[21] Resource management is critical for servers to sustain performance under varying loads from multiple clients. Servers allocate CPU cycles, memory, and storage dynamically to process requests, with multi-threaded designs preventing single connections from monopolizing resources by isolating blocking operations like disk I/O.[21] High-level load balancing distributes incoming requests across multiple server instances or tiers, such as via proxy servers, to prevent overload and ensure equitable resource utilization without a single point of failure.[20]Communication

Request-Response Cycle

The request-response cycle forms the fundamental interaction mechanism in the client-server model, enabling clients to solicit services or data from servers through a structured exchange of messages. In this cycle, the client, acting as the initiator, constructs and transmits a request message containing details such as the desired operation and any required parameters. The server, upon receiving the request, parses it, performs necessary processing—such as authentication, resource allocation, and execution of the requested task—and then formulates and sends back a response message with the results or relevant data. This pattern ensures a clear division of labor, with the client focusing on user interface and request formulation while the server handles computation and resource management.[23][24] The cycle unfolds in distinct stages to maintain reliability and orderliness. First, the client initiates the request, often triggered by user input or application logic, by packaging the necessary information into a message and dispatching it over the network connection. Second, the server accepts the incoming request, validates it (e.g., checking permissions), and executes the associated operations, which may involve querying a database or performing computations. Third, the server generates a response encapsulating the outcome, such as retrieved data or confirmation of action, and transmits it back to the client. Finally, the client processes the received response, updating its state or displaying results to the user, thereby completing the interaction. These stages emphasize the sequential nature of the exchange, promoting efficient resource use in distributed environments.[23][24] Request-response cycles can operate in synchronous or asynchronous modes, influencing performance and responsiveness. In synchronous cycles, the client blocks or pauses execution after sending the request, awaiting the server's response before proceeding, which simplifies programming but may lead to delays in high-latency networks. Asynchronous cycles, conversely, allow the client to continue other operations without blocking, using callbacks or event handlers to process the response upon arrival, thereby enhancing scalability for applications handling multiple concurrent interactions. The choice between these modes depends on the application's requirements for immediacy and throughput.[25][26] Error handling is integral to the cycle's robustness, addressing potential failures in transmission or processing. Mechanisms include timeouts, where the client aborts the request if no response arrives within a predefined interval, preventing indefinite hangs. Retries enable the client to resend the request automatically upon detecting failures like network interruptions, often with exponential backoff to avoid overwhelming the server. Additionally, responses incorporate status indicators—such as success codes (e.g., 200 OK) or error codes (e.g., 404 Not Found)—allowing the client to interpret and respond appropriately to outcomes like resource unavailability or authorization failures. These features ensure graceful degradation and maintain system reliability.[23][23] A conceptual flow of the request-response cycle can be visualized as a sequential diagram:- Client Initiation: User or application triggers request formulation and transmission to server.

- Network Transit: Request travels via established connection (e.g., socket).

- Server Reception and Processing: Server receives, authenticates, executes task (e.g., database query).

- Response Generation and Transit: Server builds response with status and data, sends back.

- Client Reception and Rendering: Client receives, parses, and applies response (e.g., updates UI).