Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shaoxing wine

View on Wikipedia| Shaoxing wine | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

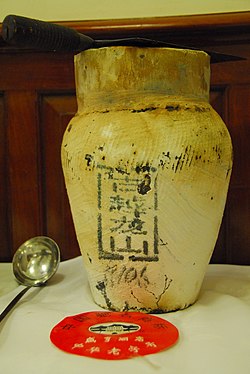

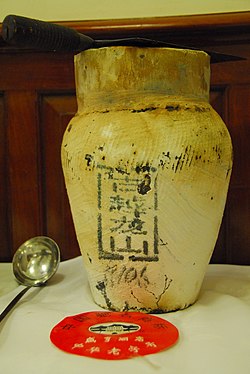

A smaller scaled version of the classic Shaoxing wine container | |||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 绍兴酒 | ||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 紹興酒 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Shaoxing wine (alternatively spelled Shaohsing, Hsiaohsing, or Shaoshing) is a variety of Chinese Huangjiu ("yellow wine") made by fermenting glutinous rice, water, and wheat-based yeast.

It is produced in Shaoxing, in the Zhejiang province of eastern China, and is widely used as both a beverage and a cooking wine in Chinese cuisine. It is internationally well known and renowned throughout mainland China, as well as in Taiwan and Southeast Asia.[1][2]

The content of peptides in Shaoxing wine is high; however, their potential taste properties have not yet been studied.[3]

Production

[edit]The traditional method involves manually stirring rice mash with a type of wooden hoe every four hours, in order to help the yeast break down the sugars evenly. Known as kāi pá (Chinese: 開耙), it is an essential skill to produce wine neither bitter nor sour. Another important skill of the winemaker is to assess the fermentation by listening to the vat for the sound of bubbling.[4]

In addition to glutinous rice, Shaoxing wine can also be produced with sorghum or millet.[5]

It is also bottled for domestic consumption and for shipping internationally. Aged wines are referred to by year of brewing, similar to grape vintage year (Chinese: 陳年; pinyin: chén nián).

Wines sold overseas are generally used in cooking, and can contain spices and extra salt.[6] Mislabeling wines from regions other than Shaoxing as "Shaoxing wine" is a "common fraudulent practice".[2]

Prominent producers

[edit]- Di Ju Tang (Chinese: 帝聚堂)

- Kuai Ji Shan (Chinese: 會稽山 named after a local mountain)[4]

- Tu Shao Jiu (Chinese: 土紹酒)

- Nü Er Hong (Chinese: 女兒紅[4])

In 2020, a revenue of 4.3 billion yuan ($664 million) was reported by 80 rice wine makers in Shaoxing.[5]

History

[edit]Rice wine has been produced in China since around 770 to 221 BC and was generally for ceremonial use. During the late Qing dynasty, educated councilors from Shaoxing spread the popularity of wine consumption throughout the country and was an essential part of Chinese banquets.[5] Large quantities are made and stored in clay jars over long periods of time.[1]

In 1980s, Hong Kong, interest in Nü Er Hong, a brand of Shaoxing wine, grew due to nostalgic interest in mainland Chinese traditions, as well as references in popular martial arts novels of the time. Tung Chee-hwa celebrated his appointment as first Chief Executive of Hong Kong with Nü Er Hong.[4]

In China, the beverage's popularity has waned in favor of other types of alcohol, and it has a reputation for being "old-fashioned," although it is still used for cooking. Outside of Asia it is mostly regarded as a cooking wine.[5]

Classification

[edit]| Name | Sugar content (g/L) |

Type | Ethanol by vol. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yuanhong Jiu (Chinese: 元紅酒; lit. 'primary red alcohol') | < 5 | Dry wine | > 14.5 |

| Jiafan Jiu (Chinese: 加飯酒; lit. 'alcohol with added rice') | 5–30 | Semi-dry wine | > 16.0 |

| Huadiao Jiu (Chinese: 花雕酒; lit. 'alcohol in jars engraved with flowers'[6]) | |||

| Shanniang Jiu Chinese: 善酿酒; lit. 'well-fermented alcohol' | 30–100 | Sweet wine (moelleux) | > 15.0 |

| Xiangxue Jiu (Chinese: 香雪酒; lit. 'snow-flavored alcohol') | 200 | Sweet wine (doux) | > 13.0 |

| Fenggang Jiu (Chinese: 封缸酒; lit. 'jug alcohol') |

Usage

[edit]

Better quality Shaoxing wine can be drunk as a beverage and in place of rice at the beginning of a meal. This type of Shaoxing wine is generally of higher quality and is more expensive than the cooking grades seen in the supermarkets, which contain added salt. When at home, some families will drink their wine out of rice bowls, which is also the serving style at Xian Heng Inn. If not served at a meal, Shaoxing wine can also accompany peanuts or other common snacks.

Nǚ Ér Hong (Chinese: 女兒紅; lit. 'daughter's red (wine)') is a tradition in Shaoxing when a girl is born into the family. A jar of wine is brewed and stored underground on the day of the daughter's birth, and dug out and opened for consumption on her wedding day as celebration.[4]

Huang jiu (Chinese: 黄酒; pinyin: huáng jiǔ; lit. 'Yellow Alcohol'), as it is known locally, is also well known for its use in meat dishes, in addition to being an ingredient in many dishes of Chinese cuisine. It is a key ingredient of Mao Zedong's favourite dish of braised pork belly with scallion greens – what he called his "brain food" that helped him defeat his enemies.[9] The following is a sample list of other common Shaoxing wine-marinated dishes. It is not limited to the following:[1]

- Drunken chicken (Chinese: 醉雞)

- Drunken shrimp (Chinese: 醉蝦)

- Drunken gizzard (Chinese: 醉腎)

- Drunken fish (Chinese: 醉魚)

- Drunken crab (Chinese: 醉蟹)

- Drunken liver (Chinese: 醉肝)

- Drunken tofu (Chinese: 醉豆腐乾)

- Drunk phoenix talon (Chinese: 醉鳳爪)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c TVB show Natural Heritage 天賜良源 episode 1 January 30, 2008. Shaoxing wine exclusive

- ^ a b Shen, Fei; Yang, Danting; Ying, Yibin; Li, Bobin; Zheng, Yunfeng; Jiang, Tao (2012-02-01). "Discrimination Between Shaoxing Wines and Other Chinese Rice Wines by Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and Chemometrics". Food and Bioprocess Technology. 5 (2): 786–795. doi:10.1007/s11947-010-0347-z. ISSN 1935-5149. S2CID 95391310.

- ^ Yu, Haiyan; Wang, Xiaoyu; Xie, Jingru; Ai, Lianzhong; Chen, Chen; Tian, Huaixiang (2022-08-02). "Isolation and identification of bitter-tasting peptides in Shaoxing rice wine using ultra-performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry combined with taste orientation strategy". Journal of Chromatography A. 1676 463193. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2022.463193. ISSN 0021-9673. PMID 35709603. S2CID 249298851.

- ^ a b c d e f Tao, Ni (2021-08-26). "Nü Er Hong: How a rice winemaker created a legendary Chinese brand". SupChina. Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- ^ a b c d Tao, Ni (2021-05-13). "In Shaoxing, young winemakers attempt to revive China's original spirit". SupChina. Retrieved 2021-09-25.

- ^ a b "Chinese cooking wine brings tangy depth to, well . . . everything". Salon. 2021-05-07. Retrieved 2021-09-25.

- ^ Shaoxingwine.com

- ^ Lee, Yuan-Kun (2006). Microbial Biotechnology: Principles and Applications (2nd revised ed.). World Scientific. ISBN 981-256-676-7.

- ^ Malcolm Moore (29 January 2010). "China sets standard for Chairman Mao's favourite dish". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 5 February 2012.