Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shastasaurus

View on Wikipedia

| Shastasaurus Temporal range: Late Triassic,

| |

|---|---|

| |

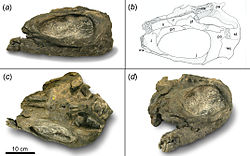

| Partial skull of Shastasaurus pacificus (UCMP 9017) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Ichthyosauria |

| Suborder: | †Longipinnati |

| Node: | †Merriamosauria |

| Family: | †Shastasauridae Merriam, 1895 |

| Genus: | †Shastasaurus Merriam, 1895 |

| Type species | |

| †Shastasaurus pacificus Merriam, 1895

| |

| Species | |

|

†S. pacificus | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Shastasaurus ("Mount Shasta lizard") is an extinct genus of ichthyosaur from the Late Triassic.[2] Specimens have been found in the United States, Canada, and China.[3]

Description

[edit]

Shastasaurus lived during the late Triassic period. The type species, S. pacificus, is known from California, with the name Shastasaurus directly referencing Shasta County, Northern California, where the type specimen was found.[4] S. pacificus was a medium-sized ichthyosaur, measuring over 7 metres (23 ft) in length.[5] A second possible species of Shastasaurus, S. sikanniensis, is known from the Pardonet Formation British Columbia, dating to the middle Norian age (about 210 million years ago).[6] By comparison, S. sikanniensis was one of the largest known ichthyosaurs, similar in size to modern-day cetaceans, measuring up to 21 metres (69 ft) in length and weighing 81.5 metric tons (89.8 short tons).[7]

Shastasaurus was highly specialized, and differed considerably from other ichthyosaurs. It was very slender in profile. S. sikanniensis had a ribcage slightly less than 2 metres (6.6 ft) deep despite a distance of over 7 metres (23 ft) between its flippers.[6] With its unusually short, toothless snout (compared to the longer, toothed, dolphin-like snouts of most ichthyosaurs), it had been proposed that Shastasaurus was a suction feeder (or filled a similar ecological niche as extant beaked whales), preying primarily on soft-bodied cephalopods.[8] However, current research indicates that the jaws of shastasaurid ichthyosaurs do not fit the suction-feeding profile, since their short and narrow hyoid bones are unsuitable to withstand impact forces for such kind of feeding,[9] and since some species like Shonisaurus had robust sectorial teeth with gut contents of mollusk shells and vertebrates.[10][11]

It is unknown whether Shastasaurus had a dorsal fin; however, the smaller, more basal ichthyosaur Mixosaurus had one.[12] The upper fluke of the tail was probably much less-developed than the shark-like tails found in later species.[13]

Species and synonyms

[edit]

The type species of Shastasaurus is S. pacificus, from the late Carnian of northern California. It is known only from fragmentary remains, which have led to the assumption that it was a 'normal' ichthyosaur in terms of proportions, especially skull proportions. Several species of long-snouted ichthyosaur were referred to Shastasaurus based on this misinterpretation, but are now placed in other genera (including Callawayia and Guizhouichthyosaurus).[8] Elizabeth Nicholls and Makoto Manabe considered this species as a nomen dubium in 2000.[14]

Shastasaurus may include a second species, Shastasaurus liangae. It is known from several good specimens, and was originally placed in the separate genus Guanlingsaurus. Complete skulls show that it had an unusual short and toothless snout. S. pacificus probably also had a short snout, although its skull is incompletely known.[8] However, a new juvenile specimen discovered in 2013 shows that the hyoid bone of Guanlingsaurus is much shorter, and considered it as a distinct genus based on phylogenetic analysis.[15]

S. sikanniensis was originally described in 2004 as a large species of Shonisaurus. However, this classification was not based on any phylogenetic analysis, and the authors also noted similarities with Shastasaurus. The first study testing its relationships, in 2011, supported the hypothesis that it was indeed more closely related to Shastasaurus than to Shonisaurus, and it was reclassified as Shastasaurus sikanniensis.[8] However, a 2013 analysis supported the original classification, finding it more closely related to Shonisaurus than to Shastasaurus.[15] In the 2019 study, S. sikanniensis was pertained within the genus Shastasaurus.[16] In the 2021 analysis, S. sikanniensis forms a clade with Shonisaurus, indicating that it is closer to Shonisaurus than to Shastasaurus.[17] Specimens belonging to S. sikanniensis have been found in the Pardonet Formation British Columbia, dating to the middle Norian age.[6]

In 2009, Shang & Li reclassified the species Guizhouichthyosaurus tangae as Shastasaurus tangae. However, later analysis showed that Guizhouichthyosaurus was in fact closer to more advanced ichthyosaurs, and so cannot be considered a species of Shastasaurus.[8]

Dubious species that were referred to this genus include S. carinthiacus (Huene, 1925) from the Austrian Alps and S. neubigi (Sander, 1997) from the German Muschelkalk.[3] S. neubigi, however, was re-described and reassigned to its own genus, Phantomosaurus.[18]

Synonyms of S. / G. liangae:

Guanlingichthyosaurus[19] liangae Wang et al., 2008 (lapsus calami)

Synonyms of S. pacificus:

Shastasaurus alexandrae Merriam, 1902

Shastasaurus osmonti Merriam, 1902

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "†Shastasaurus Merriam 1895 (ichthyosaur)". Paleobiology Database. Fossilworks. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Hilton, Richard P., Dinosaurs and Other Mesozoic Animals of California, University of California Press, Berkeley 2003 ISBN 0-520-23315-8, at pages 90-91.

- ^ a b Shang Qing-Hua, Li Chun (2009). "On the occurrence of the ichthyosaur Shastasaurus in the Guanling Biota (Late Triassic), Guizhou, China" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 47 (3): 178–193.

- ^ Merriam, John C. (1895). "On some Reptilian Remains from the Triassic of Northern California". American Journal of Science. 50 (295): 55.

- ^ Michael W. Maisch and Andreas T. Matzke (2000). "The Ichthyosauria" (PDF). Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde: Serie B. 298: 1–159. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18.

- ^ a b c Nicholls, E.L.; Manabe, M. (2004). "Giant ichthyosaurs of the Triassic - a new species of Shonisaurus from the Pardonet Formation (Norian: Late Triassic) of British Columbia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (3): 838–849. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0838:GIOTTN]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Sander, P.M.; Griebeler, E.M.; Klein, N.; Juarbe, J.V.; Wintrich, T.; Revell, L.J.; Schmitz, L. (2021). "Early giant reveals faster evolution of large body size in ichthyosaurs than in cetaceans" (PDF). Science. 374 (6575) eabf5787. doi:10.1126/science.abf5787. PMID 34941418. S2CID 245444783.

- ^ a b c d e Sander P, Chen X, Cheng L, Wang X (2011). Claessens L (ed.). "Short-Snouted Toothless Ichthyosaur from China Suggests Late Triassic Diversification of Suction Feeding Ichthyosaurs". PLOS ONE. 6 (5) e19480. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...619480S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019480. PMC 3100301. PMID 21625429.

- ^ Motani R, Tomita T, Maxwell E, Jiang D, Sander P (2013). "Absence of Suction Feeding Ichthyosaurs and Its Implications for Triassic Mesopelagic Paleoecology". PLOS ONE. 8 (12) e66075. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...866075M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066075. PMC 3859474. PMID 24348983.

- ^ Kelley, Neil P.; Irmis, Randall B.; dePolo, Paige E.; Noble, Paula J.; Montague-Judd, Danielle; Little, Holly; Blundell, Jon; Rasmussen, Cornelia; Percival, Lawrence M.E.; Mather, Tamsin A.; Pyenson, Nicholas D. (December 2022). "Grouping behavior in a Triassic marine apex predator". Current Biology. 32 (24): 5398–5405.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.11.005. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 36538877. S2CID 254874088.

- ^ Druckenmiller, Patrick S.; Kelley, Neil; Whalen, Michael T.; Mcroberts, Christopher; Carter, Joseph G. (2014-09-19). "An Upper Triassic (Norian) ichthyosaur (Reptilia, Ichthyopterygia) from northern Alaska and dietary insight based on gut contents". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (6): 1460–1465. Bibcode:2014JVPal..34.1460D. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.866573. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 129908740.

- ^ Renesto, Silvio; Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Fogliazza, Fabio; Ragni, Cinzia (2020). "New findings reveal that the middle Triassic ichthyosaur Mixosaurus cornalianus is the oldest amniote with a dorsal fin". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 65. doi:10.4202/app.00731.2020. ISSN 0567-7920.

- ^ Wallace, D.R. (2008). Neptune's Ark: From Ichthyosaurs to Orcas. University of California Press, 282pp.

- ^ Nicholls, E. L.; Manabe, M. (2001). "A new genus of ichthyosaur from the Late Triassic Pardonet Formation of British Columbia: bridging the Triassic-Jurassic gap". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 38 (6): 983–1002. Bibcode:2001CaJES..38..983N. doi:10.1139/cjes-38-6-983.

- ^ a b Ji, C.; Jiang, D. Y.; Motani, R.; Hao, W. C.; Sun, Z. Y.; Cai, T. (2013). "A new juvenile specimen of Guanlingsaurus (Ichthyosauria, Shastasauridae) from the Upper Triassic of southwestern China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (2): 340–348. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.723082. S2CID 83784699.

- ^ Moon, B. (2019). "A new phylogeny of ichthyosaurs (Reptilia: Diapsida)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 17: 1–27.

- ^ Bindellini G; Wolniewicz AS; Miedema F; Scheyer TM (2021). "Cranial anatomy of Besanosaurus leptorhynchus Dal Sasso & Pinna, 1996 (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria) from the Middle Triassic Besano Formation of Monte San Giorgio, Italy/Switzerland: taxonomic and palaeobiological implications". PeerJ. 9 (e11179). doi:10.7717/peerj.11179. hdl:11573/1682932.

- ^ Maisch, M. W.; Matzke, A. T. (2006). "The braincase of Phantomosaurus neubigi (Sander, 1997), an unusual ichthyosaur from the Middle Triassic of Germany". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (3): 598–607. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[598:TBOPNS]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Xiaofeng, W.; Bachmann, G. H.; Hagdorn, H.; Sander, P. M.; Cuny, G.; Xiaohong, C.; Chuanshang, W.; Lide, C.; Long, C.; Fansong, M.; Guanghong, X. U. (2008). "The Late Triassic Black Shales of the Guanling Area, Guizhou Province, South-West China: A Unique Marine Reptile and Pelagic Crinoid Fossil Lagerstätte". Palaeontology. 51: 27–61. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00735.x.

Shastasaurus

View on GrokipediaDiscovery and naming

Initial discovery

The first specimens of Shastasaurus were discovered in the spring of 1895 in the Hosselkus Limestone of Shasta County, California, along a ridge between Squaw Creek and Pit River. These fossils were found by James Perrin Smith of Stanford University, who sent the remains to paleontologist John C. Merriam at the University of California, Berkeley. Merriam identified the bones as belonging to a large reptile similar to known ichthyosaurs but of unprecedented size, and he formally described and named the genus Shastasaurus pacificus later that year based on these fragmentary postcranial elements, including vertebrae and ribs, which formed the type specimen. The Hosselkus Limestone dates to the late Carnian stage of the Late Triassic, approximately 235 million years ago.[4] Merriam's initial description spurred further expeditions, leading to additional partial skeletons and skulls of Shastasaurus from sites in California and nearby Nevada during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These early finds provided the basis for preliminary reconstructions of the animal as an enormous marine reptile, though the fragmentary nature of the material limited detailed anatomical understanding at the time. Subsequent discoveries expanded the known range of Shastasaurus beyond the United States. In 1997, a large, nearly complete skeleton was unearthed from the Pardonet Formation in northeastern British Columbia, Canada, representing the holotype of what was initially described as Shonisaurus sikanniensis in 2004 but later reassigned to Shastasaurus sikanniensis (though this classification remains debated in recent phylogenetic analyses). Further specimens have been reported from the Xiaowa Formation in Guizhou Province, China, including articulated skeletons attributed to Shastasaurus liangae, originally described under the genus Guanlingsaurus in 2000.Etymology and historical research

The genus name Shastasaurus was established by American paleontologist John C. Merriam in 1895, combining "Shasta," in reference to Shasta County in northern California near the discovery site and close to Mount Shasta, with the Greek saurus (lizard). Merriam's foundational work continued with his 1905 monograph, which detailed skeletal elements from multiple specimens, solidifying the genus's diagnostic traits such as robust vertebral centra and limb proportions, and establishing Shastasaurus as a key representative of Late Triassic ichthyosaurs. Throughout the 20th century, researchers revised interpretations of Shastasaurus, with Alfred Sherwood Romer's 1966 synthesis in Vertebrate Paleontology integrating it into broader ichthyosaur phylogeny, emphasizing its primitive features within the group and distinguishing it from more derived forms. A notable contribution came from Elizabeth L. Nicholls and Makoto Manabe in 2001, who designated the type species S. pacificus a nomen dubium due to the holotype's fragmentary nature and lack of distinguishing characters, prompting reevaluation of generic validity. Early 20th-century reconstructions often portrayed Shastasaurus with an elongated snout akin to other ichthyosaurs, but this misconception was overturned by studies in the 2010s employing CT scans and 3D modeling on well-preserved skulls, which demonstrated a notably short, toothless rostrum adapted for suction feeding on soft-bodied prey like cephalopods.[5] These advancements, building on Merriam's initial framework, have refined understandings of Shastasaurus's anatomy and ecology, highlighting its role in Triassic marine reptile diversification.Taxonomy and classification

Higher classification

Shastasaurus belongs to the superorder Ichthyopterygia, a group of extinct marine reptiles that evolved from terrestrial ancestors during the Early Triassic and achieved high levels of aquatic adaptation.[6] Within Ichthyopterygia, it is classified in the order Ichthyosauria and the family Shastasauridae, which comprises early-diverging ichthyosaurs primarily known from the Triassic period.[7] Shastasauridae is characterized by its members' enormous body sizes, often exceeding 10 meters in length, and represents one of the earliest radiations of large-bodied ichthyosaurs in marine ecosystems.[5] Phylogenetic analyses position Shastasaurus as one of the most basal genera within Ichthyosauria, emerging in the early Late Triassic (Carnian stage, approximately 237–227 million years ago).[5] A 2011 cladistic study by Motani et al., based on a modified dataset of cranial and postcranial characters, recovered Shastasaurus as basal within the clade Merriamosauria, with primitive features such as a shortened rostrum and reduced dentition adapted for suction feeding.[5] This contrasts with more derived post-Triassic ichthyosaurs, such as those in the family Ophthalmosauridae (e.g., Ophthalmosaurus from the Jurassic and Cretaceous), which exhibit elongated snouts, sharper teeth, and enhanced streamlining for faster swimming.[7] Subsequent revisions, including a 2021 phylogenetic analysis by Bindellini et al. incorporating updated character matrices from Triassic specimens, reinforce Shastasaurus's basal position but suggest a closer relationship to Shonisaurus within Shastasauridae, forming a monophyletic subclade defined by shared synapomorphies like abbreviated snouts and high vertebral counts.[7] These primitive traits, including large overall size and a relatively short, robust skull compared to the longer-snouted Mixosauridae (an earlier, smaller-bodied family), highlight Shastasaurus's role in the initial diversification of giant predators during the Triassic recovery from the Permian-Triassic extinction.[5]Species and synonyms

The type species of the genus Shastasaurus is S. pacificus, established by Merriam (1895) based on fragmentary skeletal elements, including vertebrae and limb bones, collected from the Upper Triassic Hosselkus Limestone in Shasta County, California. Due to the holotype's incompleteness and lack of diagnostic features, Nicholls and Manabe (2001) classified it as a nomen dubium, which has contributed to taxonomic instability within the genus as no other species can be definitively referred without a valid type. S. alexandrae, described by Merriam (1902) based on a partial skull and vertebrae from the same locality, is considered a valid species distinct from S. pacificus. S. osmonti, also from Merriam (1902) and represented by isolated postcranial elements from the same formation, is regarded as a junior synonym of S. alexandrae due to overlapping morphology and stratigraphic equivalence. Other early names applied to North American Triassic ichthyosaur remains later attributed to Shastasaurus include the obsolete Delphinosaurus (Merriam, 1905) and Perrinosaurus, which encompassed nondiagnostic bones now recognized as belonging to various shastasaurids.| Species | Original Description | Status and Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. pacificus | Merriam, 1895 (holotype: UCMP 9273, fragmentary vertebrae and limbs, Hosselkus Limestone, California) | Type species; nomen dubium due to inadequate holotype | Merriam (1895); Nicholls & Manabe (2001) |

| S. alexandrae | Merriam, 1902 (holotype: partial skull and vertebrae, Hosselkus Limestone, California) | Valid species; distinguished by cranial features | Merriam (1902); Maisey (2018)[8] |

| S. altispinus | Camp, 1989 (holotype: LACM 3920, vertebrae and neural spines, Antimonio Formation, Sonora, Mexico) | Valid species; notable for tall neural spines | Camp (1989); López-Arellano (2016)[2] |

| S.? liangae | Yin et al., 2000 (as Guanlingsaurus liangae; holotype: GMPKU P1301, near-complete skeleton, Xiaowa Formation, Guizhou, China) | Questionably valid; synonymized with Shastasaurus based on shared short rostrum, edentulous jaws, and vertebral proportions | Yin et al. (2000); Motani et al. (2011)[5] |

| S.? sikanniensis | Nicholls & Manabe, 2004 (as Shonisaurus sikanniensis; holotype: LACM 128319, nearly complete skeleton, Pardonet Formation, British Columbia, Canada) | Questionably valid; transferred to Shastasaurus in phylogenetic analyses but subject to debate | Nicholls & Manabe (2004); Motani et al. (2011)[5] |