Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

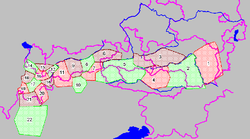

Central Eastern Alps

View on WikipediaThe Central Eastern Alps (German: Zentralalpen or Zentrale Ostalpen), also referred to as Austrian Central Alps (German: Österreichische Zentralalpen) or just Central Alps,[1] comprise the main chain of the Eastern Alps in Austria and the adjacent regions of Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Italy and Slovenia. South of them is the Southern Limestone Alps.

Key Information

The term "Central Alps" is very common in the Geography of Austria as one of the seven major landscape regions of the country. "Central Eastern Alps" is usually used in connection with the Alpine Club classification of the Eastern Alps (Alpenvereinseinteilung, AVE). The Central Alps form the eastern part of the Alpine divide, its central chain of mountains, as well as those ranges that extend or accompany it to the north and south.

The highest mountain in the Austrian Central Alps is Grossglockner at 3,798 metres (12,461 ft).

Location

[edit]The Central Alps have the highest peaks of the Eastern Alps, and are located between the Northern Limestone Alps and the Southern Limestone Alps, from which they differ in geological composition.

The term "Central Eastern Alps" may also be used more broadly to refer to a larger area of the Eastern Alps, mainly located in Austria, extending from the foot of the Bergamasque Alps at Lake Como and the Bernina Range in the Graubünden canton of eastern Switzerland along the Liechtenstein shore of the Rhine in the west as far as to the lower promontories east of the river Mur including the Hochwechsel in Austrian Styria. The valleys of the rivers Inn, Salzach and Enns mark their northern boundary, the Drau river (roughly corresponding to the Periadriatic Seam) their southern border. In the proposed SOIUSA system, the "Central-eastern Alps" include the Rhaetian Alps, of which the Bernina Range includes the 4,049-meter Piz Bernina in Switzerland, the easternmost 4,000-meter peak of the Alps. In the AVE system, however, the full list of mountain groups in the Alpine Club classification of the Eastern Alps includes the Bernina and neighboring ranges within the Western Limestone Alps, not the Central Eastern Alps as the Alpine Club defines them.

Central Alps as a major landscape region in Austria

[edit]In Austria, the Eastern Alps are divided into the Northern Alps, the Greywacke zone, the Central Alps and the Southern Alps. The latter lie partly in South Carinthia, but mainly in Northeast Italy.

The Central and Northern Alps are separated by the Northern Longitudinal Trough (nördliche Längstalfurche), the line Klostertal–Arlberg–Inn Valley–Salzach Valley as far as Lake Zell–Wagrain Heights–Upper Enns Valley–Schober Pass–Mürz Valley Alps–Semmering–southern Vienna Basin.[2] The Central Alps and Southern Alps are separated from one another by the Southern Longitudinal Valley (südlichen Längstalzug) Puster Valley (Rienz Valle–Toblach Field–upper Drava (Drau) Valley)–Drava Valley–Klagenfurt Basin–Meža (Mieß), or the Periadriatic Seam, which is not entirely identical with the Southern Longitudinal Trough.

Geomorphology

[edit]The range has the highest summits in the Eastern Alps and is the most glaciated. In the transition zone between the East and West Alps, its peaks clearly dominate the region to the west (Piz d'Err, Piz Roseg). On the perimeter, however, there are also less high, often less rugged mountain chains, like the Gurktal Alps and the eastern foothills.

The Eastern Alps is separated from the Western Alps by a line from Lake Constance to Lake Como along the Alpine Rhine valley and via the Splügen Pass.

Geology

[edit]

and several windows, regional nappes and islands

The Central Alps consist mainly of the gneiss and slate rocks of the various Austroalpine nappes (Lower and Upper Austroalpine), with the exception of the Hohe Tauern and Engadine windows, where they are composed mostly of Jurassic rock and limestones and, locally, (Bergell and Rieserferner) also of granite. The Austroalpine nappes are thrusted over the Penninic nappe stack. Massifs of autochthonous, crystalline rock, which hardly moved at all during Alpine folding, do not occur in the Central Alps – unlike the case in the Western Alps. The aforementioned granite intruded near the fracture zone of the Periadriatic Seam. The Western Alps do not have this division into the Northern Limestone Alps, Central Alps and Southern Limestone Alps.

The Austroalpine submerges itself at the eastern edge of the Alps under the Tertiary sediments of the Alpine Foreland in the east and the Pannonian Basin. This fracture zone exhibits active volcanism (e.g. in the Styrian thermal region).

Alpine Club classification

[edit]The Central Eastern Alps also comprise the following ranges of the West Eastern Alps according to AVE classification, which geologically belong to the Southern Alps and are also subsumed under the Western Limestone Alps division.:

- ^ The Kitzbühel Alps and the adjacent Salzburg Slate Alps as part of the Greywacke zone are either counted as part of the Northern Limestone Alps or the Central Alps – geologically they form the bedrock of the Limestone Alps, and the slip zone, on which the latter were thrust northwards

| AVE- No. |

Name | Map | Country | Highest mountain | Height (m) | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 63 | Plessur Alps | Aroser Rothorn | 2,980 |

| ||

| 64 | Oberhalbstein Alps | Piz Platta | 3,392 |

| ||

| 65 | Albula Alps | Piz Kesch | 3,418 |

| ||

| 66 | Bernina Group | Piz Bernina | 4,049 |

| ||

| 67 | Livigno Alps | Cima de’ Piazzi | 3,439 |

| ||

| 68 | Bergamasque Alps[a] | Pizzo di Coca | 3,052 |

|

- ^ The Bergamasque Alps are – geologically and petrologically – part of the Southern Limestone Alps, and thus the Southern Alps

The Ortler Alps as well as the Sobretta-Gavia Group are also sometimes classified with the Central Alps, because they lie north of the geological fault of the Periadriatic Seam; in a general regional geographic sense, however, they are seen as part of the Southern Limestone Alps, because they are found south of the longitudinal trough Veltlin (Adda)–Vintschgau (Etsch).[3] Also in terms of rock, the Ortler main crest is part of the Southern Limestone Alps.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Not to be confused with the other meaning of Central Alps i.e. the Swiss Alps.

- ^ Alps in Austria-Forum (in German) (at AEIOU)

- ^ Peter Holl: Alpenvereinsführer Ortleralpen

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Central Eastern Alps at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Central Eastern Alps at Wikimedia Commons