Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sniffle

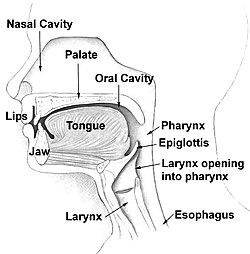

View on WikipediaA sniffle is the instinctive action of inhaling quickly in order to prevent mucus from flowing from one's nasal cavity, as an alternative to blowing the nose.

Physiology

[edit]

For a fraction of a second, the performer inhales strongly, pulling mucus from the outer part of the nasal cavity higher up, even into the sinus. This action is generally repeated every few seconds or minutes as the pulled mucus returns to the outer part of the nasal cavity, until the mucus stops returning (due to the mucus having drained into the throat, the nose having been blown to remove the mucus, or some other factor).[citation needed]

Sniffling and having a runny nose are not always associated with sneezing or coughing.

Sniffling is not necessarily related to illness.[1] In addition to allergies and colds, it can be a result of being in cold temperatures, as a way to hold back tears, and as a tic.[2]

When it is related to illness, sniffling can aggravate or extend the illness (relative to not sniffling), by returning to the sinuses whatever substance (such as allergens) the mucus that is sniffled back was removing.

Reducing the need to sniffle generally involves reducing the symptoms causing the excessive mucus, often through antihistamines or decongestants, or treating the root cause, such as by using an air purifier to remove allergens. More immediate relief can be had by either nasal irrigation or blowing the nose, most often into a facial tissue or handkerchief. Some seek out a bathroom and blow their noses into a sink, which they then wash along with their hands.[citation needed]

Psychology

[edit]Many people are unconscious of their sniffling, hence the stereotype of children as more apt to sniffle, since they are less conscious of stigma. The sharp high-pitched noise of a sniffle can easily become both inaudible to the performer, who experiences it as a relief, and irritating to those around the sniffler.[3]

Sociology

[edit]In many cultures, blowing one's nose in public is considered impolite, and in reaction, people can make a habit of sniffling. In many other cultures, it is considered very impolite to sniffle.[4][5][better source needed]

"The sniffles" can also refer by metonymy to the common cold, though colds often do not result in sniffles and sniffles often are not caused by colds.[citation needed]

The sound of sniffles can trigger fight-or-flight reactions or anger (with results up to and including involuntary violence) in some with misophonia.[6][7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "9 Ways to Stay Sniffle-Free - coldflusinus - Health.com". www.health.com. Archived from the original on 2010-11-03.

- ^ "Sniffle Definition & Meaning".

- ^ "What is Noise Anxiety? (With pictures)". 9 September 2023.

- ^ "Petit manuel de politesse et de savoir-vivre à l'usage de la jeunesse/Ce qu'il faut faire et ce qu'il faut éviter lorsqu'on est en société chez soi, ou chez les autres".

- ^ "To Blow or to Sniff — Culture Shock for an Expat". InterNations. Retrieved 2025-11-19.

- ^ Salamon, Maureen (2023-09-01). "When everyday noises upset you". Harvard Health. Retrieved 2025-11-19.

- ^ "What Is Misophonia?". WebMD. Retrieved 2025-11-19.