Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Piriform cortex

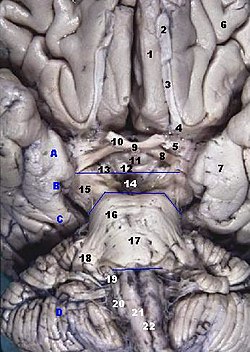

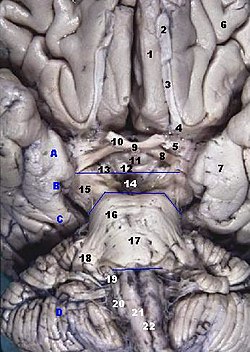

View on Wikipedia| Piriform cortex | |

|---|---|

Human brainstem anterior (piriform cortex not labeled, but most of it is visible near #7) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cortex piriformis |

| MeSH | D066195 |

| NeuroNames | 165 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1097 |

| FMA | 62484 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The piriform cortex, or pyriform cortex, is a region in the brain, part of the rhinencephalon situated in the cerebrum. The function of the piriform cortex relates to the sense of smell.

Structure

[edit]The piriform cortex is part of the rhinencephalon situated in the cerebrum.

In human anatomy, the piriform cortex has been described as consisting of the cortical amygdala, uncus, and anterior parahippocampal gyrus.[1] More specifically, the human piriform cortex is located between the insula and the temporal lobe, anteriorly and laterally of the amygdala.[2][3]

Function

[edit]The function of the piriform cortex relates to olfaction, which is the perception of smell. This has been particularly shown in humans for the posterior piriform cortex.[2]

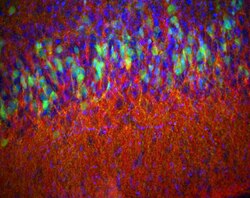

The piriform cortex in rodents and some primates has been shown to harbor cells expressing markers of plasticity such as doublecortin and PSA-NCAM which are modulated by the noradrenergic neurotransmitter system.[4][5]

Clinical significance

[edit]The piriform cortex contains a critical, functionally defined epileptogenic trigger zone, "Area Tempestas".[6] From this site in piriform cortex chemical and electrically evoked seizures can be triggered. It is the site of action for the proconvulsant action of chemoconvulsants.[7]

Other animals

[edit]

Sometimes called the olfactory cortex, olfactory lobe or paleopallium, piriform cortical regions are present in the brains of amphibians, reptiles and mammals.

The piriform cortex is among three areas that emerge in the telencephalon of amphibians, situated caudally to a dorsal area, which is caudal to a hippocampal area. Further along the phylogenic timeline, the telencephalic bulb of reptiles as viewed in a cross section of the transverse plane extends with the archipallial hippocampus folding toward the midline and down as the dorsal area begins to form a recognizable cortex.

As mammalian brains developed, volume of the dorsal cortex increased in slightly greater proportion, as compared proportionally with increased overall brain volume, until it enveloped the hippocampal regions. Recognized as neopallium or neocortex, enlarged dorsal areas envelop the paleopallial piriform cortex in humans and Old World monkeys.

Among taxonomic groupings of mammals, the piriform cortex and the olfactory bulb become proportionally smaller in the brains of phylogenically younger species. The piriform cortex occupies a greater proportion of the overall brain and of the telencephalic brains of insectivores than in primates. The piriform cortex continues to occupy a consistent albeit small and declining proportion of the increasingly large telencephalon in the most recent primate species while the volume of the olfactory bulb becomes less in proportion.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Estomih Mtui; Gregory Gruener (2006). Clinical Neuroanatomy and Neuroscience: With STUDENT CONSULT Online Access. Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 368. ISBN 978-1-4160-3445-2.

- ^ a b Howard, J. D., Plailly, J., Grueschow, M., Haynes, J. D., & Gottfried, J. A. (2009). Odor quality coding and categorization in human posterior piriform cortex. Nature neuroscience, 12(7), 932-938. Supplementary material, p.4

- ^ Mai, J. K. & Paxinos, G. (2008). Atlas of the human brain, 3rd edition. San Diego:: Academic Press. Coronal Atlas – Plate 8 (anterior view). online: http://www.thehumanbrain.info/head_brain/hn_horizontal_atlas/horizontal.html

- ^ Fasemore, Thandi M.; Patzke, Nina; Kaswera-Kyamakya, Consolate; Gilissen, Emmanuel; Manger, Paul R.; Ihunwo, Amadi O. (2018). "Elsevier: Article Locator". Neuroscience. 372: 46–57. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.12.037. PMID 29289719.

- ^ Vadodaria, Krishna C.; Yanpallewar, Sudhirkumar U.; Vadhvani, Mayur; Toshniwal, Devyani; Liles, L. Cameron; Rommelfanger, Karen S.; Weinshenker, David; Vaidya, Vidita A. (2017-03-22). "Noradrenergic regulation of plasticity marker expression in the adult rodent piriform cortex". Neuroscience Letters. 644: 76–82. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2017.02.060. PMC 5526722. PMID 28237805.

- ^ Piredda S, Gale K (October 1985). "A crucial epileptogeneic site in the deep prepiriform cortex". Nature. 317 (6038): 623–5. doi:10.1038/317623a0. PMID 4058572.

- ^ Löscher W, Ebert U (December 1996). "The role of the piriform cortex in kindling". Prog. Neurobiol. 50 (5–6): 427–81. doi:10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00036-6. PMID 9015822.