Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

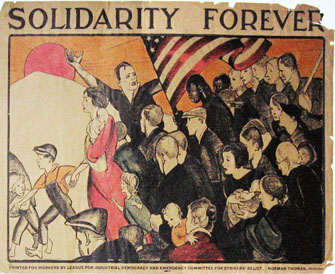

Solidarity Forever

View on Wikipedia| "Solidarity Forever" | |

|---|---|

| Song | |

| Written | 1914–1915 |

| Composer | Traditional music |

| Lyricist | Ralph Chaplin |

"Solidarity Forever" is a trade union anthem written in 1915 by Ralph Chaplin promoting the use of solidarity amongst workers through unions. It is sung to the tune of "John Brown's Body" and "The Battle Hymn of the Republic". Although it was written as a song for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), other union movements, such as the AFL–CIO, have adopted the song as their own. The song has been performed by musicians such as Utah Phillips, Pete Seeger, and John Darnielle. It was redone by Emcee Lynx and The Nightwatchman. It is still commonly sung at union meetings, protests and rallies in the United States, Australia, New Zealand and Canada, and has also been sung at conferences of the Australian Labor Party and the Canadian New Democratic Party. This may have also inspired the hymn of the consumer cooperative movement, "The Battle Hymn of Cooperation", which is sung to the same tune.

It has been translated into several other languages, including French, German, Polish, Spanish, Swahili and Yiddish.[1]

Lyrics

[edit]When the union's inspiration through the workers' blood shall run,

There can be no power greater anywhere beneath the sun;

Yet what force on earth is weaker than the feeble strength of one,

But the union makes us strong.

Chorus:

Solidarity forever!

Solidarity forever!

Solidarity forever!

For the union makes us strong.

Is there aught we hold in common with the greedy parasite,

Who would lash us into serfdom and would crush us with his might?

Is there anything left to us but to organize and fight?

For the union makes us strong.

Chorus

It is we who plowed the prairies; built the cities where they trade;

Dug the mines and built the workshops, endless miles of railroad laid;

Now we stand outcast and starving ’midst the wonders we have made;

But the union makes us strong.

Chorus

All the world that's owned by idle drones is ours and ours alone.

We have laid the wide foundations; built it skyward stone by stone.

It is ours, not to slave in, but to master and to own.

While the union makes us strong.

Chorus

They have taken untold millions that they never toiled to earn,

But without our brain and muscle not a single wheel can turn.

We can break their haughty power, gain our freedom when we learn

That the union makes us strong.

Chorus

In our hands is placed a power greater than their hoarded gold,

Greater than the might of armies, multiplied a thousand-fold.

We can bring to birth a new world from the ashes of the old

For the union makes us strong.

Composition

[edit]Ralph Chaplin began writing "Solidarity Forever" in 1913, while he was working as a journalist covering the Paint Creek–Cabin Creek strike of 1912 in Kanawha County, West Virginia, having been inspired by the resolve and high spirits of the striking miners and their families who had endured the violent strike (which killed around 50 people on both sides) and had been living for a year in tents. He completed the song on January 15, 1915, in Chicago, on the date of a hunger demonstration[clarification needed]. Chaplin was a dedicated Wobbly, a writer at the time for Solidarity, the official IWW publication in the eastern United States, and a cartoonist for the organization. He shared the analysis of the IWW, embodied in its famed "Preamble", printed inside the front cover of every Little Red Songbook.[2]

The Preamble begins with a classic statement of a two-class analysis of capitalism: "The working class and the employing class have nothing in common." The class struggle will continue until the victory of the working class: "Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the earth and the machinery of production, and abolish the wage system." The Preamble denounces trade unions as incapable of coping with the power of the employing class. By negotiating contracts, the Preamble states, trade unions mislead workers by giving the impression that workers have interests in common with employers.[3]

The Preamble calls for workers to build an organization of all "members in any one industry, or in all industries". Although that sounds a lot like the industrial unionism developed by the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the IWW would oppose John L. Lewis' campaign to split from the American Federation of Labor and organize industrial unions in the 1930s. The Preamble explains, "Instead of the conservative motto, 'A fair day's wage for a fair day's work,' we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword, 'Abolition of the wage system.'" The IWW embraced syndicalism, and opposed participation in electoral politics: "by organizing industrially we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old".[4]

The outlook of the Preamble is embodied in "Solidarity Forever", which enunciates several elements of the IWW's analysis. The third stanza ("It is we who plowed the prairies") asserts the primacy of the role of workers in creating value. This is echoed in stanzas four and five, which provide ethical justification for the workers' claim to "all the world." The second stanza ("Is there aught we hold in common with the greedy parasite") assumes the two antagonistic classes described in the Preamble. The first and fifth stanzas provide the strategy for labor: union solidarity. And the sixth stanza projects the outcome, a new world brought to birth "from the ashes of the old".

Chaplin was not pleased with the widespread popularity of "Solidarity Forever" in the labor movement. Late in his life, after he had become a voice opposing (State) Communists in the labor movement, Chaplin wrote an article, "Why I wrote Solidarity Forever", in which he denounced the "not-so-needy, not-so-worthy, so-called 'industrial unions' spawned by an era of compulsory unionism". He wrote that among Wobblies "there is no one who does not look with a rather jaundiced eye upon the 'success' of 'Solidarity Forever.'" "I didn't write 'Solidarity Forever' for ambitious politicians or for job-hungry labor fakirs seeking a ride on the gravy train.… All of us deeply resent seeing a song that was uniquely our own used as a singing commercial for the soft-boiled type of post-Wagner Act industrial unionism that uses million-dollar slush funds to persuade their congressional office boys to do chores for them." He added, "I contend also that when the labor movement ceases to be a Cause and becomes a business, the end product can hardly be called progress."[5]

Despite Chaplin's misgivings, "Solidarity Forever" has retained a general appeal for the wider labor movement because of the continued applicability of its core message. Some performers do not sing all six stanzas of "Solidarity Forever," typically dropping verses two ("Is there aught we hold in common with the greedy parasite") and four ("All the world that's owned by idle drones is ours and ours alone"), thus leaving out the most radical material.[6]

Modern additions

[edit]Since the 1970s women have added verses to "Solidarity Forever" to reflect their concerns as union members. One popular set of stanzas is:

- We're the women of the union and we sure know how to fight.

- We'll fight for women's issues and we'll fight for women's rights.

- A woman's work is never done from morning until night.

- Women make the union strong!

- (Chorus)

- It is we who wash the dishes, scrub the floors and clean the dirt,

- Feed the kids and send them off to school—and then we go to work,

- Where we work for half men's wages for a boss who likes to flirt.

- But the union makes us strong!

- (Chorus)[7]

A variation from Canada goes as follows:

- We're the women of the union in the forefront of the fight,

- We fight for women's issues, we fight for women's rights,

- We're prepared to fight for freedom, we're prepared to stand our ground,

- Women make the union strong.

- (Chorus)

- Through our sisters and our brothers, we can make our union strong,

- For respect and equal value we have done without too long,

- We no longer have to tolerate injustices and wrongs,

- For the union makes us strong.

- (Chorus)

- When racism in all of us is finally out and gone,

- Then the union movement will be twice as powerful and strong,

- For equality for everyone will move the cause along,

- For the union makes us strong.

- (Chorus)[8]

The centennial edition of the Little Red Songbook includes these two new verses credited to Steve Suffet:

- They say our day is over; they say our time is through,

- They say you need no union if your collar isn't blue,

- Well that is just another lie the boss is telling you,

- For the Union makes us strong!

- (Chorus)

- They divide us by our color; they divide us by our tongue,

- They divide us men and women; they divide us old and young,

- But they'll tremble at our voices, when they hear these verses sung,

- For the Union makes us strong!

- (Chorus)[9]

Pete Seeger's adaptation of the song removes the second and fourth verses and rewrites the final verse as:

- In our hands is placed a power greater than their hoarded gold

- Greater than the might of atoms, magnified a thousand fold,

- We can bring to birth a new world from the ashes of the old,

- For the union makes us strong.

- (Chorus)[10]

In popular culture

[edit]

"Solidarity Forever" is featured in the 2014 film Pride in which London organisation Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners collect funds to support the miners of a Welsh village during the 1984–1985 UK miners' strike.[11]

The Little Red Songbook by the IWW includes a satire reversion of Solidarity Forever, retitled Aristocracy Forever; mocking the adoption of the song by the AFL-CIO.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Antiwar Songs (AWS): Ralph Chaplin - Solidarity Forever". www.antiwarsongs.org.

- ^ Ralph Chaplin, Wobbly (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1948), especially pp. 167–168.

- ^ I.W.W. Songs, reprint of the 19th edition (1923) of the "Little Red Song Book" (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Co., 2003), inside front cover. Chaplin, Wobbly, p. 148, also has a clear copy of the Preamble.

- ^ I.W.W. Songs, reprint of the 19th edition (1923) of the "Little Red Song Book" (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Co., 2003), inside front cover.

- ^ Ralph Chaplin, "Why I Wrote Solidarity Forever", American West, January 1968, pp. 23, 24.

- ^ An example is the Almanac Singers' cover on Talking Union and other Union Songs, Folkways FH 5285 (1955), reissued by Smithsonian Folkways. See also The People's Songbook, ed. Waldemar Hill (Boni & Gaer, 1948) pp. 68-69.

- ^ "The Union Bug", (January–February 2004), of the United Staff Union, McFarland, WI. usu-wisconsin.org Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Activities for Activists," Education Section of the Public Service Alliance of Canada, June 2004. psac.com Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Songs of the Workers to Fan the Flames of Discontent: The Little Red Songbook, Limited Centenary Concert Edition (IWW, June 2005), pp. 4–5.

- ^ "Pete Seeger - Solidarity Forever Lyrics | Lyrics.com". www.lyrics.com. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- ^ "Pride Soundtrack". Universal Music Operations Limited. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

References

[edit]- I.W.W. Songs: To Fan the Flames of Discontent, a facsimile reprint of the 19th edition (1923) of the Little Red Song Book (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Co., 2003).

- Songs of the Workers To Fan the Flames of Discontent: The Little Red Songbook, Limited Centenary Concert Edition (IWW, June 2005).

- Ralph Chaplin, Wobbly: The Rough-and-Tumble Story of an American Radical (The University of Chicago Press, 1948), ch. 15, pp. 162–171.

- Ralph Chaplin, "Confessions of a Radical," two-part article in Empire Magazine of the Denver Post, Feb. 17, 1957, pp. 12–13, and Feb. 24, 1957, pp. 10–11.

- Ralph Chaplin, "Why I Wrote Solidarity Forever," American West, vol. 5, no. 1 (January 1968), 18–27, 73.

- Rise Up Singing page 218. Includes United Farm Workers lyrics in Spanish.

External links

[edit]- Solidarity Forever Pete Seger YouTube

- Pete Seger Solidarity Forever Solidarity Forever - Hudson Valley Area Labor Federation - March 2011 YouTube

Solidarity Forever

View on GrokipediaOrigins

Authorship and Initial Composition

Ralph Chaplin, an American journalist, artist, poet, and organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), authored the lyrics to "Solidarity Forever" in 1915.[1] He began drafting the poem during coverage of the 1912–1914 Kanawha coal miners' strike in West Virginia but completed it amid the economic hardships of early 1915.[8] On January 17, 1915, during a frigid day in Chicago, Chaplin finalized the lyrics while walking to a "Hunger Demonstration" rally organized by unemployed workers at Hull House, a settlement house known for social reform efforts.[5] [1] By then, Chaplin had been active in the IWW since joining in 1913, contributing as a prolific writer and editor for its publications, including Solidarity magazine and the Industrial Worker newspaper, where he honed propaganda skills through verse and illustration.[9] The song debuted in IWW circles shortly after its completion, appearing in print for the first time in the ninth edition of the IWW's Little Red Songbook in 1916.[3] Its immediate resonance as a call for class solidarity and industrial unionism led to widespread singing at IWW meetings and strikes, cementing its status as an unofficial anthem within months.[10]Historical Inspiration and Context

In the early 1910s, the United States experienced rapid industrialization amid massive immigration, with over 8.8 million arrivals between 1900 and 1915 swelling the industrial workforce, particularly in factories, mines, and mills where unskilled laborers predominated.[11] This influx provided employers with abundant cheap labor, enabling suppression of wages and extension of work hours; non-union manufacturing workers often earned as little as 16-20 cents per hour in sectors like steel, while standard shifts exceeded 10-12 hours daily, six days a week, with minimal safety protections or compensation for injuries.[12] Economic pressures from scientific management practices further intensified exploitation, fragmenting tasks to deskill workers and reduce bargaining power, as employers prioritized output over worker welfare in booming industries like coal, textiles, and munitions.[13] The Ludlow Massacre of April 20, 1914, exemplified the violent clashes arising from these conditions during the Colorado Coalfield War, where approximately 11,000 miners struck against the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company for union recognition, higher pay, and an eight-hour day after enduring company scrip systems and evictions.[14] Company guards and Colorado National Guard troops attacked a strikers' tent colony with machine guns and set it ablaze, killing at least 21 people, including two women and 11 children, which galvanized national outrage and radicalized labor sentiments toward collective defense against such brutality.[15] This event, coupled with over 1,500 strikes recorded in 1915 alone—many involving immigrants demanding basic reforms—highlighted systemic employer tactics, including private militias like the Baldwin-Felts detective agency and court injunctions that legally barred picketing and union activities, framing solidarity as a pragmatic counter to isolated worker vulnerability.[16][17] In response, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), founded in 1905, promoted "One Big Union" industrial unionism as an alternative to the American Federation of Labor's craft-based model, which limited membership to skilled, often native-born workers and pursued incremental reforms through arbitration.[18] The IWW's philosophy emphasized class-wide organization across skills, industries, and ethnicities to wage direct action against capitalism's root causes, viewing fragmented craft unions as ineffective against mass unskilled labor pools and employer divide-and-conquer strategies like importing strikebreakers.[19] By 1915, amid escalating unrest, this approach underscored solidarity not as mere sentiment but as a causal necessity for workers to counter coordinated capital resistance, influencing cultural expressions of labor resistance.[20]Lyrics and Musical Elements

Full Lyrics and Structure

"Solidarity Forever" features four original verses composed by Ralph Chaplin, each comprising four lines and followed by a repeating four-line chorus, emphasizing the transformative power of worker unity.[3] The lyrics highlight the contrast between individual frailty and collective strength, vivid imagery of workers as the builders of modern industry—"It is we who plowed the prairies; built the cities where they trade"—and the assertion that production rightfully belongs to those who labor, culminating in phrases like "All the world that's owned by idle drones is ours and ours alone."[3] Verse 1When the union’s inspiration through the workers’ blood shall run,

There can be no power greater anywhere beneath the sun;

Yet what force on earth is weaker than the feeble strength of one,

But the union makes us strong.[3] Chorus

Solidarity forever,

Solidarity forever,

Solidarity forever,

For the union makes us strong.[3] Verse 2

It is we who plowed the prairies; built the cities where they trade;

Dug the mines and built the workshops, endless miles of railroad laid;

Now we stand outcast and starving midst the wonders we have made,

But the union makes us strong.[3] Chorus Verse 3

Is there aught we hold in common with the greedy parasite,

Who would lash us into serfdom and would crush us with his might?

Is there anything left to us but to organize and fight?

For the union makes us strong.[3] Chorus Verse 4

All the world that's owned by idle drones is ours and ours alone.

We have been fools, and jerked around too long to be afraid to own the world.

From the product of our labor, we can bring to birth the world,

For the union makes us strong.[3] The poetic structure prioritizes communal singability through a repetitive chorus that echoes the tune's rhythmic affirmation, with verses adhering to a loose ABCB rhyme scheme and iambic meter adapted from "John Brown's Body" to facilitate group performance at rallies.[3] This form builds progressively from the inherent weakness of isolated workers to the collective realization of their productive power, enabling the song's use as a mnemonic for solidarity.[3] Chaplin completed the lyrics on January 15, 1915, with first publication appearing in the Industrial Worker newspaper shortly thereafter.[6]