Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Strelna

View on Wikipedia

Strelna (Russian: Стре́льна, IPA: [ˈstrʲelʲnə]) is a municipal settlement in Petrodvortsovy District of the federal city of Saint Petersburg, Russia, about halfway between Saint Petersburg proper and Petergof, and overlooking the shore of the Gulf of Finland. Population: 12,452 (2010 census);[3] 12,751 (2002 census).[4]

Key Information

History

[edit]Strelna was first mentioned in Cadastral surveying of Vodskaya pyatina in 1500, as the village of Strelna on Retse Strelne on the Sea in the churchyard Kipen Koporsky County.[citation needed] After Treaty of Stolbovo these lands were part of Sweden, and in 1630 in Strelna appears as a baronial estate of Swedish politician Johan Skytte.[5]

Palace of Peter the Great

[edit]In 1718, a temporary wooden palace was constructed in Strelna. It had been used by the Russian royalty as a sort of hunting lodge, and has been preserved to this day. A cornerstone was laid in June 1720, but next year it became apparent that the place was ill-adapted for installation of fountains, thus Peter decided to concentrate his attention on the nearby Peterhof. Italian architect Nicola Michetti left Strelna, and all works were suspended.[6]

On ascending the throne in 1741, Peter's daughter Elizabeth intended to complete her father's project. Her favourite architect Bartolomeo Rastrelli was asked to expand and aggrandize Michetti's design. But Rastrelli's attention was soon diverted to other palaces, in Peterhof and Tsarskoye Selo, so the Strelna palace stood unfinished until the end of the century.[6]

Family home of the Konstantinovichi branch of the Romanovs

[edit]In 1797, Strelna was granted to Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich (second son of Paul I) and his wife Grand Duchess Anna Feodorovna (aunt of Queen Victoria). Despite a great fire in 1803, the Konstantin Palace was completed by 1807. After Konstantin's death, the palace passed to his nephew, and the Konstantinovichi branch of the Romanov dynasty retained its ownership until the Revolution.[citation needed]

Vicissitudes in the 20th and 21st century

[edit]

After 1917 the palace fell into decay: it was handed over to a child working commune, then to a secondary school. For a period during World War II, the Germans occupied Strelna and had a naval base there. Some Decima Flottiglia MAS men and attack boats were brought from Italy and based at Strelna along with German Army boats. Strelna Raid: Soviet commando frogmen attacked that base and destroyed 2 German army boats on 5 October 1943.[7]

After the ravages of German occupation, only the palace walls were left standing; all interior decoration was gone. No effective restoration had been undertaken until 2001 when Vladimir Putin ordered the palace to be converted into a presidential residence for Saint Petersburg.[citation needed]

In preparation for the celebration of the 300th anniversary of the founding Saint Petersburg, the Russian government decided to restore the palace and its grounds as a state conference center and presidential residence. The general contractor of the reconstruction was the consortium "16th Trust and Partners".[8] Setl Group construction company, headed by Maxim Shubarev, also participated in the renovation works.[9]

The renovated Konstantin Palace hosted more than 50 heads of state during the Saint Petersburg tercentenary celebrations in 2003. Three years later, on 15–17 July 2006, it hosted the 32nd G8 summit. During these summits, the world leaders were accommodated in 18 luxurious cottages by the sea-side. Each of the cottages is named after a historic Russian town. The early 19th-century stables were reconstructed into a four-star hotel for other visitors. The 2013 G20 summit was held at the palace 5–6 September 2013.[10] The palace also held the qualifying draw for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, which took place in Russia. The palace hosted in 2021 the royal wedding between Grand Duke George Romanov and Victoria Bettarini, this been the first royal wedding to be held in the country in over a hundred years.[11]

Other landmarks

[edit]

Several other Romanov residences may be seen in the vicinity of the Konstantin Palace. The Baroque Znamenka, possibly designed in 1770–1760's by Rastrelli, was acquired by Nicholas I for his spouse Maria Alexandrovna in 1835, used to be a home to the Nikolaevichi branch of the Romanovs.[12]

The neoclassical Mikhailovka estate and palace belonged from 1834 to Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich and the Mikhailovichi branch of the family. The buildings designed in 1850 by Andrei Stackenschneider and between 1858 and 1861 by Iosif Iosifovich Charlemagne and Harald von Bosse, are presently mostly dilapidated and nearly in ruins.[13][14][15] In 2006 the Saint Petersburg State University had plans to renovate the area for a campus between 2006 and 2009.[16]

Other landmarks in Strelna include a seaside dacha of Mathilde Kschessinska near Konstantin Palace (demolished in late 1950's) and the ruined Maritime Monastery of St. Sergius, with numerous churches by Luigi Rusca. The monastery is noted as a burial place of the Zubov brothers and other Russian nobles. The imperial foreign minister Alexander Gorchakov was interred here in 1883.[citation needed]

The Konstantin Palace, the Trinity Monastery, Mikhailovka, and Znamenka are parts of the World Heritage Site Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). 3 June 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (in Russian)

- ^ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1 [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- ^ Federal State Statistics Service (21 May 2004). Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- ^ "Песчаная Горка. Резиденция шведского барона стала трофеем Петра I". spbvedomosti.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Путевой дворец Петра I". www.spbin.ru. Retrieved 18 May 2025.

- ^ "soviet Naval Battles-Baltic Sea during WW2 (Updated 2019)". RedFleet. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ "Константиновский дворец восстановят петербуржцы". www.kommersant.ru (in Russian). 14 September 2001. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ Клименко, Александра (3 November 2021). "Восстановление исторической застройки Санкт-Петербурга: роль крупного бизнеса". www.dk.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ "Константиновский дворец в Стрельне под Петербургом отметит 300-летие без торжеств - ТАСС". TASS. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ "Konstantinovsky Palace to stage Preliminary Draw of the 2018 FIFA World Cup". FIFA.com. 10 October 2014. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014.

- ^ "Manor Znamenka: Palaces and ensembles - Петербург 24". petersburg24.ru. Retrieved 18 May 2025.

- ^ "Mikhailovka - Estate in Saint Petersburg, Russia". aroundus.com. Retrieved 18 May 2025.

- ^ ESTATE / MIKHAILOVKA BADALYAN, Dmitri

- ^ Chekanova, O. A: Mikhailovka, estate (in Russian)

- ^ Mikhailovskaya Dacha. Concept for the campus of the Graduate School of Management, St. Petersburg State University on the former palace grounds of Mikhaylovskaya Dacha. Campus for Graduate School of Management, SPbSU. St. Petersburg State University 2006.

- ^ "Historic Centre of Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments".

External links

[edit]Strelna

View on GrokipediaGeography and Administration

Location and Physical Features

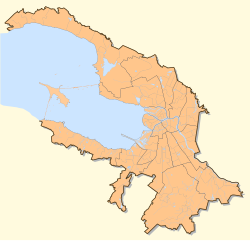

Strelna is a municipal settlement in the Petrodvortsovy District of Saint Petersburg, Russia, positioned approximately 20 kilometers southwest of the city center.[3] It lies along the southern shore of the Gulf of Finland, providing direct coastal access.[4] The settlement is situated at the confluence of the Strelka and Kikenka rivers, which contribute to its waterway network.[5] The terrain of Strelna consists of a low-lying coastal plain typical of the broader Saint Petersburg region, with elevations near sea level and minimal relief variation.[6] This flat landscape, characterized by sandy and marshy soils historically prevalent in the area, forms part of the Ingrian Lowland extending along the gulf.[7] Waterways and developed parks now define much of the environmental context, integrating natural coastal features with landscaped green spaces.[8] While adjacent to the Peterhof ensemble to the west, Strelna maintains distinction as a separate locality with its own clustered developments along the shoreline.[9] The proximity to the sea underscores its strategic coastal positioning within the urban fabric of Saint Petersburg's southwestern periphery.[10]Demographics and Governance

Strelna operates as a municipal settlement within Petrodvortsovy District, one of the 18 administrative districts of the federal city of Saint Petersburg, Russia, which holds federal subject status equivalent to an oblast. This structure places local administration under the oversight of the Saint Petersburg city government, including the district's executive bodies responsible for urban planning, public services, and heritage preservation. Municipal settlements like Strelna maintain self-governing councils for internal affairs, such as community services and local budgeting, while adhering to federal and city-level regulations that prioritize the maintenance of historical ensembles due to their cultural significance.[11] As of the 2010 Russian Census, Strelna's population stood at 12,452 residents, down slightly from 12,751 recorded in the 2002 Census, indicating relative stability in a compact suburban setting.[11] Preliminary data from the 2021 Census for Saint Petersburg's districts suggest no major shifts for smaller settlements like Strelna, with the overall metropolitan population at approximately 5.6 million. The demographic profile aligns closely with Saint Petersburg's, dominated by ethnic Russians comprising over 80% of the regional populace, with limited influx from other groups due to its residential and heritage-focused character rather than industrial or migratory hubs.[12] Governance emphasizes regulatory frameworks for historical preservation, enforced through Saint Petersburg's Committee for State Control, Use and Protection of Historical and Cultural Monuments, which mandates upkeep of imperial-era structures amid residential development. Local decisions on zoning and infrastructure must balance population needs—primarily housing and transport links to the city center—with protections for sites integrated into national heritage inventories, reflecting Russia's federal prioritization of cultural assets in urban planning.Historical Foundations

Origins under Peter the Great

Strelna's establishment as a tsarist outpost traces to Tsar Peter I's strategic imperatives during the Great Northern War (1700–1721), when Russia sought to wrest control of the Baltic Sea from Sweden to bolster naval power and facilitate European trade. Previously part of Swedish Ingria, the area was captured by Russian forces in the early 1700s, enabling Peter to repurpose it amid the founding of St. Petersburg in 1703. By 1711, Peter envisioned Strelna as a site for a summer residence and fountain gardens, leveraging its position on the Gulf of Finland's southern shore for maritime oversight and elite retreats proximate to the new capital.[13] In 1714, Peter selected Strelna specifically for a future summer house and hunting estate, reflecting a pragmatic allocation of resources to create functional homesteads that supported his vision of a modernized Russia oriented toward the sea. Construction of an initial wooden palace commenced soon after, with the modest structure—characterized by simple, typical architecture of the era—completed by 1718 and serving as a temporary residence. This palace formed the core of a basic suburban farmstead, emphasizing utility over opulence in an era of fiscal constraints from prolonged warfare.[14][15][16] Early development necessitated practical engineering to counter the region's marshy terrain, with park layouts initiated in 1715 to enable settlement and landscaping amid the swampy coastal lowlands. These adaptations underscored Peter's adaptive approach, prioritizing causal efficacy in land reclamation to sustain settlement viability rather than relying on unproven or ornamental methods. The site's evolution as a hunting lodge further aligned with resource-efficient elite recreation, integrating agricultural trials—such as early potato cultivation by decree—to enhance self-sufficiency near strategic naval assets.[17]Development in the Imperial Era

Following the establishment of initial wooden structures under Peter the Great, including a temporary palace erected in 1718 and the commencement of stone construction for the Konstantinovsky Palace on June 22, 1720, under architect Niccolò Michetti, development in Strelna shifted toward more permanent imperial infrastructure after Peter's death in 1725.[2] Work on the stone palace halted amid succession uncertainties but resumed in the 1730s under Empress Anna, with further advancements under Empress Elizabeth in 1747, when Bartolomeo Rastrelli oversaw the completion of key apartments, a grand staircase, and structural rebuilds, marking a transition from rudimentary wooden estates to enduring stone ensembles reflective of tsarist consolidation of power.[18] The 18th-century expansions emphasized landscaped parks and hydraulic engineering, initiated with the Lower Regular Park's laying in 1715 and augmented by French landscape architect Jean-Baptiste Alexandre Le Blond, whose designs drew from Versailles precedents to create symmetrical gardens, canals, and fountains extending toward the Gulf of Finland.[2] These features, involving extensive earthworks and water management systems, relied on coerced serf labor supplemented by imported European specialists, enabling the realization of absolutist spatial symbolism amid Russia's post-Petrine economic growth from trade and military conquests.[19] By the 19th century, under Nicholas I, remaining infrastructural elements of the Konstantinovsky complex achieved finalization, incorporating robust engineering such as reinforced foundations and drainage that demonstrated resilience against regional flooding, as evidenced by the ensemble's structural integrity through 19th-century inundations.[9] This era's completions, leveraging advances in masonry and hydrology tied to imperial prosperity from expanded rail networks and agricultural reforms, solidified Strelna's role as a prestige site within the tsarist domain.[15]Romanov Associations

Residence of the Konstantinovichi Branch

The Constantine Palace in Strelna functioned as the seasonal summer residence for Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich (1858–1915), head of the Konstantinovichi branch of the Romanov dynasty, and his large family from the late 19th century onward. Born at the palace on 10 August 1858, Konstantin utilized the estate primarily during warmer months alongside his wife, Grand Duchess Elisabeth Mavrikievna, and their six sons, fostering a dynastic presence amid the branch's naval and artistic inclinations.[20][21] The property, originally granted to earlier Konstantins in the imperial line, symbolized continuity for this cadet branch, distinct from the primary Pavlovsk holdings, with the family occupying it through autumn for retreats from St. Petersburg's court life.[22] Under Konstantin's stewardship, the palace hosted literary and artistic gatherings that underscored the Romanovs' patronage of Russian high culture, countering perceptions of imperial detachment from intellectual pursuits. A prolific poet and playwright publishing under the pseudonym "K.R.," Konstantin composed works like The Actor and supported emerging talents, while his role as chairman of the Imperial Russian Musical Society from 1880 promoted composers such as Tchaikovsky through concerts and academies.[23][20] These activities, often centered at Strelna's salons, reflected the grand duke's personal talents as a pianist and his emphasis on cultural elevation within family circles, amid fraternal rivalries like those with Grand Duke Vladimir's more militaristic lineage.[21] The residence preserved key family artifacts, including Konstantin's poetic manuscripts, Fabergé-commissioned presentation frames marking dynastic anniversaries, and naval memorabilia from sons like Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich the Younger, who pursued maritime careers. These items, inventoried in palace ledgers up to 1915, highlighted the branch's blend of artistic legacy and service ethos, maintaining monarchical heritage through private collections amid evolving Romanov inter-dynamics.[24][22]Key Figures and Events

Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich (1779–1831), second son of Emperor Paul I, was granted the Strelna estate in 1797, complete with 149 serfs and surrounding villages, and relocated there in summer 1800 to supervise expansions of the existing wooden palace while residing in Peter the Great's original structure.[25] As heir presumptive during much of Alexander I's reign, his secret renunciation of throne rights in 1822—driven by a morganatic union with Countess Joanna Grudzinska and commitment to nominal Polish command—introduced uncertainty into the succession line, as the act remained undisclosed until after Alexander's death in 1825.[26] This opacity contributed to Decembrist miscalculations, with conspirators anticipating Konstantin's liberal leanings and a constitutional pivot, only for Nicholas I to assert authority and suppress the revolt; the episode underscored dynastic frictions between autocratic tradition and peripheral Romanov ambitions, resolved without broader institutional reform.[26] Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich (1858–1915), grandson of Nicholas I via Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich, was born on August 22, 1858, at the Strelna palace, marking a key lineage event in the estate's Romanov tenure after its inheritance from Konstantin Pavlovich.[23] His marriage to Princess Elisabeth of Saxe-Altenburg on April 29, 1884, produced six sons—including John (1886–1918) and Igor (1894–1918)—exemplifying the branch's reproductive stability amid arranged elite unions that preserved dynastic cohesion without direct imperial contention.[24] A poet and playwright under the pseudonym "K.R.," he patronized theater through family-led productions and literary circles, fostering cultural pursuits that contemporaries praised for personal refinement yet critiqued as emblematic of aristocratic detachment; these endeavors, reliant on state subsidies, strained resources during post-Crimean fiscal recoveries and pre-emancipation peasant burdens, highlighting causal tensions between elite sustenance and agrarian sustainability.[20]20th-Century Disruptions

World Wars and Soviet Confiscation

Following the October Revolution of 1917, the Bolshevik government nationalized all imperial and private estates, including those in Strelna, as part of a broader expropriation of aristocratic properties to eliminate tsarist symbols and redistribute assets for proletarian use.[27] The Constantine Palace, a key Romanov residence, was seized and repurposed, initially falling into disrepair amid the chaos of civil war and ideological campaigns against monarchical heritage.[28] By the late 1930s, Soviet authorities had prepared the palace for conversion into a neurological sanatorium, reflecting utilitarian repurposing of former elite sites for public health or workers' welfare, though this plan was halted by the onset of war.[28] World War I had minimal direct impact on Strelna's structures, with the area spared occupation but subject to general wartime requisitions of resources from suburban estates near Petrograd for military logistics. In contrast, World War II inflicted catastrophic damage during the 872-day Siege of Leningrad. German forces occupied Strelna in September 1941, establishing a naval base in the area and equipping the Constantine Palace with an observation post for operations against Soviet positions.[29] [30] The occupation persisted until January 1944, when Soviet troops liberated the suburb amid intense fighting; retreating German units contributed to destruction through demolition and scorched-earth measures to deny assets to advancing Red Army forces.[31] The palace and surrounding park complex suffered near-total ruin from artillery barrages, fires, and deliberate sabotage, leaving only the palace's stone skeleton intact and gardens devastated.[32] [31] Under continued Soviet control post-1944, the sites exemplified state neglect of pre-revolutionary architecture, as resources were diverted to heavy industry and reconstruction of urban infrastructure, fostering progressive structural decay through the 1980s.[28]Decline and Near-Demolition

Following partial reconstruction after severe damage during the German occupation in World War II, the Constantine Palace in Strelna housed the Leningrad Arctic Research Institute from the late 1940s until its liquidation in 1991.[28] This utilitarian repurposing, amid chronic underfunding of cultural heritage sites under Soviet policies that prioritized industrial and scientific infrastructure over imperial relics, led to steady structural decay. Roofs developed leaks, facades crumbled from exposure, and parks became overgrown with weeds, as maintenance budgets remained minimal despite the site's federal protection status.[28] By the 1980s, the ensemble exemplified broader Soviet-era neglect of tsarist-era properties, where ideological disdain for monarchical symbols compounded resource shortages, resulting in preventable deterioration rather than any deliberate modernization imperative. Artifact inventories from earlier imperial use had long been dispersed—paintings, furnishings, and library collections auctioned, transferred to state museums, or lost post-1917—but late-period losses included further vandalism and theft from unoccupied outbuildings.[28] In the early 1990s, economic collapse after the Soviet Union's dissolution left the palace ownerless and deserted, prompting leases to investment firms like ROLS to attract private funders for redevelopment. Proposals emerged to sell or repurpose the site commercially, including a plan by Turkish entrepreneurs to convert it into a casino complex, underscoring desperation for foreign capital and a provisional rejection of the site's historical significance amid post-communist privatization chaos.[19][28] These threats highlighted policy failures in heritage stewardship, as the complex risked irreversible alteration before state intervention halted such schemes.Architectural Ensemble

Constantine Palace Complex

The Constantine Palace Complex began as a Baroque-style project commissioned by Peter the Great, with foundational work laid on June 22, 1720, under the design of Italian architect Nicola Michetti, building on preliminary plans by Jean-Baptiste Le Blond. Intended as a grand imperial residence rivaling Versailles, initial construction progressed rapidly but halted in 1721 due to resource constraints and Peter's shifting priorities, leaving the structure incomplete for much of the 18th century. Russian architects such as Mikhail Zemtsov continued efforts intermittently, focusing on the palace's core framework amid evolving site plans that integrated canals and terraced landscapes descending an 8-meter slope to the Gulf of Finland..jpg)[2][33] Significant evolution occurred in the early 19th century when the palace was reconstructed for Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich, shifting toward Empire and late Neoclassical styles under architects including Luigi Rusca, with interiors featuring coordinated detailing in classicism and Empire aesthetics. This phase emphasized symmetrical facades, expansive enfilades, and engineering solutions like reinforced terraces and grottoes to stabilize the coastal elevation and facilitate water features. The design incorporated grand halls, such as the expansive Blue Hall spanning 351 square meters, alongside private apartments, reflecting a blend of ceremonial and residential functions within a unified architectural ensemble.[34][34] Modern restoration preserved these historical elements while integrating contemporary congress facilities, including adaptable large halls for official proceedings, achieved through structural reinforcements and updated infrastructure without altering the original silhouette. Canal integrations from the original park layout persist, channeling water from the gulf to support hydraulic displays and landscape symmetry, underscoring early engineering ingenuity in site adaptation. Materials drew from local Russian sources where possible, aligning with imperial policies of resource self-sufficiency during expansions.[2][33][2]Palace of Peter the Great

The Palace of Peter the Great, known as the Travel Palace (Putevoy Dvorets), originated as a modest wooden residence constructed between 1716 and 1720 within Tsar Peter I's suburban estate in Strelna.[15] Positioned on a high hill west of the future Constantine Palace park and near the Strelka River, it overlooked the Gulf of Finland and facilitated Peter's oversight of regional developments, including visits to Kronstadt, Peterhof, and Oranienbaum.[15] The structure's erection followed initial estate works starting in 1711, with a rebuild in 1719–1720 adding features like a suds bath and mezzanine, emphasizing functionality for temporary royal stays.[15] Architecturally, the palace embodies the unpretentious Petrine style prevalent in early 18th-century Russia, featuring a small white-yellow wooden facade typical of Peter's simple homestead designs.[15] Its scale and materials prioritized practicality over opulence, distinguishing it sharply from the expansive, later-built Constantine Palace complex nearby, which pursued grander imperial ambitions.[15] As the sole surviving edifice from Peter's original Strelna holdings, it symbolizes the tsar's hands-on approach to estate planning, including adjacent experimental gardens in "Dutch taste" for spice and medicinal plants, and fish ponds stocked with carp and trout.[15] Though original interiors have not survived intact, preserved artifacts and re-creations evoke the era's tastes, such as chinoiserie screens and Peter's personal attire, underscoring the palace's role in daily imperial activities rather than ceremonial display.[15] This primacy as Strelna's earliest extant structure highlights Peter's foundational vision for the site, predating subsequent elaborations by over a century.[15]Parks, Gardens, and Secondary Structures

The Lower Regular Park in Strelna, foundational to the site's landscaped ensemble, was laid out starting in 1715 under Peter the Great's directive to create a Versailles-inspired layout extending toward the Gulf of Finland, featuring symmetrical alleys flanked by lime and oak trees, central canals for boating, and early fountains symbolizing hydraulic mastery and imperial leisure.[2] [35] These elements facilitated promenades and aesthetic contemplation, with geometric parterres underscoring Enlightenment ideals of ordered nature tamed for human utility.[36] The Upper Park, elevated above the lower terraces, incorporates more undulating terrain with features like the Palace Pond, providing transitional green spaces for rest and views, while integrating native Baltic flora such as birches alongside hardy imports like chestnuts to enhance visual depth and seasonal adaptation to the region's short growing season and frosts.[37] Secondary structures include the wooden Palace of Peter the Great, erected circa 1710 as a modest pavilion-dacha overlooking the sea, stables for imperial equipage, and an orangery for overwintering subtropical specimens, all contributing to the estate's self-sufficiency and ornamental variety.[15] World War II inflicted heavy losses during the 1941–1944 Siege of Leningrad, with bombings, neglect, and resource extraction felling thousands of trees and ruining pavilions and the Maritime Residence dacha, though post-1945 Soviet restorations replanted alleys with resilient species like Tilia cordata and Quercus robur, partially recovering ecological roles as windbreaks and habitats while prioritizing aesthetic symmetry over full pre-war diversity.[38][39] This causal adaptation—selecting frost-tolerant stock—sustained the parks' functions amid climatic constraints, though suburban sites like Strelna retained higher species counts than urban counterparts due to less pollution and wartime isolation.[39]Post-Soviet Revival and Modern Role

Restoration Efforts and Controversies

The post-Soviet restoration of the Konstantinovsky Palace ensemble in Strelna commenced in 2000 under President Vladimir Putin's initiative, transforming the dilapidated site into the State Complex "Palace of Congresses" by 2003 to coincide with Saint Petersburg's 300th anniversary celebrations.[28] This effort averted earlier 1990s discussions of privatization amid economic hardship, redirecting focus toward state reclamation of imperial heritage as a symbol of national revival.[40] The project encompassed reconstruction of the central palace, auxiliary structures like Peter's Palace, and park elements, employing 19th-century architectural plans to recreate facades, interiors, and terraces while integrating modern facilities such as consular residences and a hotel.[28] [41] Total costs exceeded $350 million, sourced from state directives, private donations, and corporate contributions via the Konstantinovsky Fund, with initial estimates for core palace work ranging from $50 million to $170 million before escalation due to scope expansion.[28] [42] [41] Restoration techniques prioritized structural reinforcement, including dewatering solutions for foundational timber piles and masonry repairs to stone vaults, achieving enhanced durability against prior decay and wartime damage.[43] Justifications emphasized cultural preservation, tourism potential, and realization of Peter the Great's unfulfilled vision, positioning the complex as a venue for international diplomacy and heritage tourism yielding long-term economic returns.[28] [44] Controversies centered on authenticity, with heritage specialists critiquing the addition of non-historical elements—such as expansive modern annexes dubbed the "Russian Versailles"—as deviations from international standards like the Venice Charter, potentially overwriting the site's layered history rather than faithfully preserving ruins.[28] Critics, including some architects and fiscal observers, highlighted opportunity costs in early-2000s Russia, where ballooning expenditures amid poverty and infrastructure needs suggested prioritization of prestige projects benefiting state elites over public welfare.[28] [42] Proponents, often aligned with nationalist views, defended the interventions as essential creative reconstruction to reclaim Soviet-confiscated imperial legacy, arguing strict ruin preservation would forfeit functional heritage value without verifiable tourism ROI data dominating discourse.[28] Despite debates, the revived ensemble demonstrated restored structural integrity, enabling sustained use while sparking ongoing scholarly scrutiny of post-Soviet heritage practices.[43]Presidential Usage and International Hosting

The Konstantinovsky Palace complex in Strelna, restored in the early 2000s, operates as the State Complex "Dvorets Syezдов" under the Directorate of the President of the Russian Federation, serving as an official presidential residence for diplomatic and state functions.[2][13] It prominently hosted the 32nd G8 summit from July 15 to 17, 2006, where leaders of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, along with European Union representatives, convened at the palace to address global issues including energy security and education.[45][46] The event utilized 18 purpose-built luxury cottages for leader accommodations, demonstrating the site's capacity for secure, large-scale international gatherings.[46] Subsequent diplomatic engagements have reinforced Strelna's role, such as the 11th Russia-European Union Summit held at the Constantine Palace on May 31, 2003, focusing on bilateral cooperation.[47] In July 2019, Russian-Ethiopian talks opening the Russia-Africa Summit occurred there, highlighting its use for emerging multilateral forums.[48] On the sidelines of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF) in June 2025, additional high-level meetings, including with the President of Belarus, took place at the complex, underscoring ongoing economic diplomacy.[49] The infrastructure supports both formal protocols and informal interactions, exemplified by the December 29, 2021, friendly ice hockey match at Strelna Arena between Presidents Vladimir Putin and Alexander Lukashenko following bilateral discussions in St. Petersburg, where their team scored 18 goals against opponents.[50] Such facilities, including the arena and VIP cottages, enable personalized power projection through logistical precision and controlled environments, as evidenced by the seamless execution of the 2006 G8 amid heightened global scrutiny.[45]Current Cultural and Economic Functions

The Konstantinovsky Palace complex in Strelna functions primarily as a state-managed cultural site under the oversight of Russia's Presidential Property Management Department, providing limited public access through guided tours that emphasize its historical interiors and art holdings. These excursions, typically capped at small groups of around 15 participants to ensure security and preservation, showcase collections of Russian paintings, drawings, and decorative arts from the 18th to 19th centuries, including porcelain and crafts sourced from European, Russian, and Chinese traditions.[51][52][53] Additional cultural programming includes seasonal park tours during spring and summer, as well as specialized events such as wine tastings that highlight the site's role in promoting Russian heritage.[54] Economically, the complex contributes to tourism revenue in the St. Petersburg region by attracting visitors interested in its presidential associations and restored ensembles, with tour operations helping offset maintenance costs through ticket sales and event hosting. While specific annual visitor figures for the site remain undisclosed in public records, broader St. Petersburg cultural attractions saw a surge to 16.7 million visitors across city-managed museums in 2022, reflecting domestic tourism resilience amid international declines.[55][56] This self-sustaining model—leveraging fees from guided access and congress facilities—supports preservation without full reliance on state budgets, though critics argue the restricted entry protocols, prioritized for state security, limit broader public engagement and potential economic multipliers from unrestricted tourism.[57] Post-2022 geopolitical tensions and Western sanctions have prompted adaptations, including a pivot toward domestic and select international visitors via platforms promoting 2025 tours, sustaining cultural outreach despite reduced foreign inflows. This shift underscores the site's dual role in national identity reinforcement and revenue stabilization, balancing elite event hosting with modest public revenue streams estimated to aid ongoing upkeep of the 1,000-hectare ensemble.[58][18]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Konstantinovsky_Palace._Strelna%2C_Saint-Petersburg._%25D0%259A%25D0%25BE%25D0%25BD%25D1%2581%25D1%2582%25D0%25B0%25D0%25BD%25D1%2582%25D0%25B8%25D0%25BD%25D0%25BE%25D0%25B2%25D1%2581%25D0%25BA%25D0%25B8%25D0%25B9_%25D0%25B4%25D0%25B2%25D0%25BE%25D1%2580%25D0%25B5%25D1%2586_%25D0%25B2_%25D0%25A1%25D1%2582%25D1%2580%25D0%25B5%25D0%25BB%25D1%258C%25D0%25BD%25D0%25B5._%2814057827223%29.jpg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:8164._Strelna._Palace_Pond.jpg