Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tiling window manager

View on Wikipedia

In computing, a tiling window manager is a window manager with the organization of the screen often dependent on mathematical formulas to organise the windows into a non-overlapping frame. This is opposed to the more common approach used by stacking window managers, which allow the user to drag windows around, instead of windows snapping into a position. This allows for a different style of organization, although it departs from the traditional desktop metaphor.

History

[edit]Xerox PARC

[edit]The first Xerox Star system (released in 1981) tiled application windows, but allowed dialog boxes and property windows to overlap.[1] Later, Xerox PARC also developed CEDAR[2] (released in 1982), the first windowing system using a tiled window manager.

Various vendors

[edit]Next in 1983 came Andrew WM, a complete tiled windowing system later replaced by X11. Microsoft's Windows 1.0 (released in 1985) also used tiling (see sections below). In 1986 came Digital Research's GEM 2.0, a windowing system for the CP/M which used tiling by default.[3] One of the early (created in 1988) tiling WMs was Siemens' RTL, up to today a textbook example because of its algorithms of automated window scaling, placement, and arrangement, and (de)iconification. RTL ran on X11R2 and R3, mainly on the "native" Siemens systems, e.g., SINIX. Its features are described by its promotional video.[4][5] The Andrew Project (AP or tAP) was a desktop client system (like early GNOME) for X with a tiling and overlapping window manager.

MacOS X 10.11 El Capitan released in September 2015 introduces new window management features such as creating a full-screen split view limited to two app windows side-by-side in full screen by holding down the full-screen button in the upper-left corner of a window.[6]

Dynamic window manager

[edit]In computing, a dynamic window manager is a tiling window manager where windows are tiled based on preset layouts between which the user can switch. Layouts typically have a main area and a secondary area. The main area usually shows one window, but one can also change the number of windows in this area. Its purpose is to reserve more space for the more important window(s). The secondary area shows the other windows. Tiling window managers that don't use layouts are called manual tiling window managers. They let the user decide where windows should be placed.

Tiling window managers

[edit]Microsoft Windows

[edit]

The first version (Windows 1.0) featured a tiling window manager, partly because of litigation by Apple claiming ownership of the overlapping window desktop metaphor. But due to complaints, the next version (Windows 2.0) followed the desktop metaphor. All later versions of the operating system stuck to this approach as the default behaviour.

The built-in Microsoft Windows window manager has, since Windows 2.0, followed the traditional stacking approach by default. It can also act as a rudimentary tiling window manager.

To tile windows, the user selects them in the taskbar and uses the context menu choice Tile Vertically or Tile Horizontally. Choosing Tile Vertically will cause the windows to tile horizontally but take on a vertical shape, while choosing Tile Horizontally will cause the windows to tile vertically but take on a horizontal shape. These options were later changed in Windows Vista to Show Windows Side by Side and Show Windows Stacked, respectively.

Windows 7 added "Aero Snap" which adds the ability to drag windows to either side of the screen to create a simple side-by-side tiled layout, or to the top of the screen to maximize. Windows 8 introduced Windows Store apps; unlike desktop applications, they did not operate in a window, and could only run in full screen, or "snapped" as a sidebar alongside another app, or the desktop environment.[7]

Along with allowing Windows Store apps to run in a traditional window, Windows 10 enhanced the snapping features introduced in Windows 7 by allowing windows to be tiled into screen quadrants by dragging them to the corner, and adding "Snap Assist" — which prompts the user to select the application they want to occupy the other half of the screen when they snap a window to one half of the screen, and allows the user to automatically resize both windows at once by dragging a handle in the center of the screen.[8]

Windows 10 also supports FancyZones, a more complete tiling window manager facility allowing customized tiling zones and greater user control, configured through Microsoft PowerToys.

Windows 11 added more built-in tiling options, activated by hovering the mouse pointer over the maximize button.

3rd-party replacements

[edit]- AquaSnap - made by Nurgo Software. Freeware, with an optional "Professional" license.

- Amethyst for windows - dynamic tiling window manager along the lines of amethyst for MacOS.

- bug.n – open source, configurable tiling window manager built as an AutoHotKey script and licensed under the GNU GPL.[9]

- MaxTo — customizable grid, global hotkeys. Works with elevated applications, 32-bit and 64-bit applications, and multiple monitors.[10]

- WS Grid+ – move and/or resize window's using a grid selection system combining benefits of floating, stacking, and tiling. It provides keyboard/mouse shortcuts to instantly move and resize a window.

- Stack – customizable grid (XAML), global hotkeys and/or middle mouse button. Supports HiDPI and multiple monitors.[11][12]

- Plumb — lightweight tiling manager with support for multiple versions of Windows. Supports HiDPI monitors, keyboard hotkeys, and customization of hotkeys (XAML).[13]

- workspacer — an MIT-licensed tiling window manager for Windows 10 that aims to be fast and compatible. Written and configurable using C#.[14]

- dwm-win32 — port of dwm's general functionality to win32. Is MIT-licensed and is configured by editing a config header in the same style as dwm.[15]

- GlazeWM — a tiling window manager for Windows inspired by i3 and Polybar.

- Komorebi — a window manager for Microsoft Windows SO written in Rust. Like bspwm it does not handle key-binding on its own, so users have to use AHK or WHKD to manage the shortcuts. Komorebi also has a GUI User Friendly version called Komorebi UI.

- Whim -- dynamic window manager that is built using WinUI 3 and the .NET framework.

X Window System

[edit]In the X Window System, the window manager is a separate program. X itself enforces no specific window management approach and remains usable even without any window manager. Current X protocol version X11 explicitly mentions the possibility of tiling window managers. The Siemens RTL Tiled Window Manager (released in 1988) was the first to implement automatic placement/sizing strategies. Another tiling window manager from this period was the Cambridge Window Manager developed by IBM's Academic Information System group.

In 2000, both larswm and Ion released a first version.

List of tiling window managers for X

[edit]- awesome – a dwm derivative with dynamic window tiling,[16][17] floating, and tagging, written in C and configurable and extensible in Lua. It was the first WM to be ported from Xlib to XCB, and supports D-Bus, pango, XRandR, and Xinerama.

- bspwm – a small tiling window manager that represents windows as the leaves of a full binary tree. It does not handle key-binds on its own, requiring another program (e.g. sxhkd) to translate input to X events.[18]

- Compiz – a compositing window manager available for usage without leaving familiar interfaces such as the ones from GNOME, KDE Plasma or Mate. One of its plugins (called Grid) allows the user to configure several keybindings to move windows to any corner, with five different lengths. There are also options to configure default placement for specific windows. The plugins can be configured through the Compiz Config Settings Manager / CCSM.

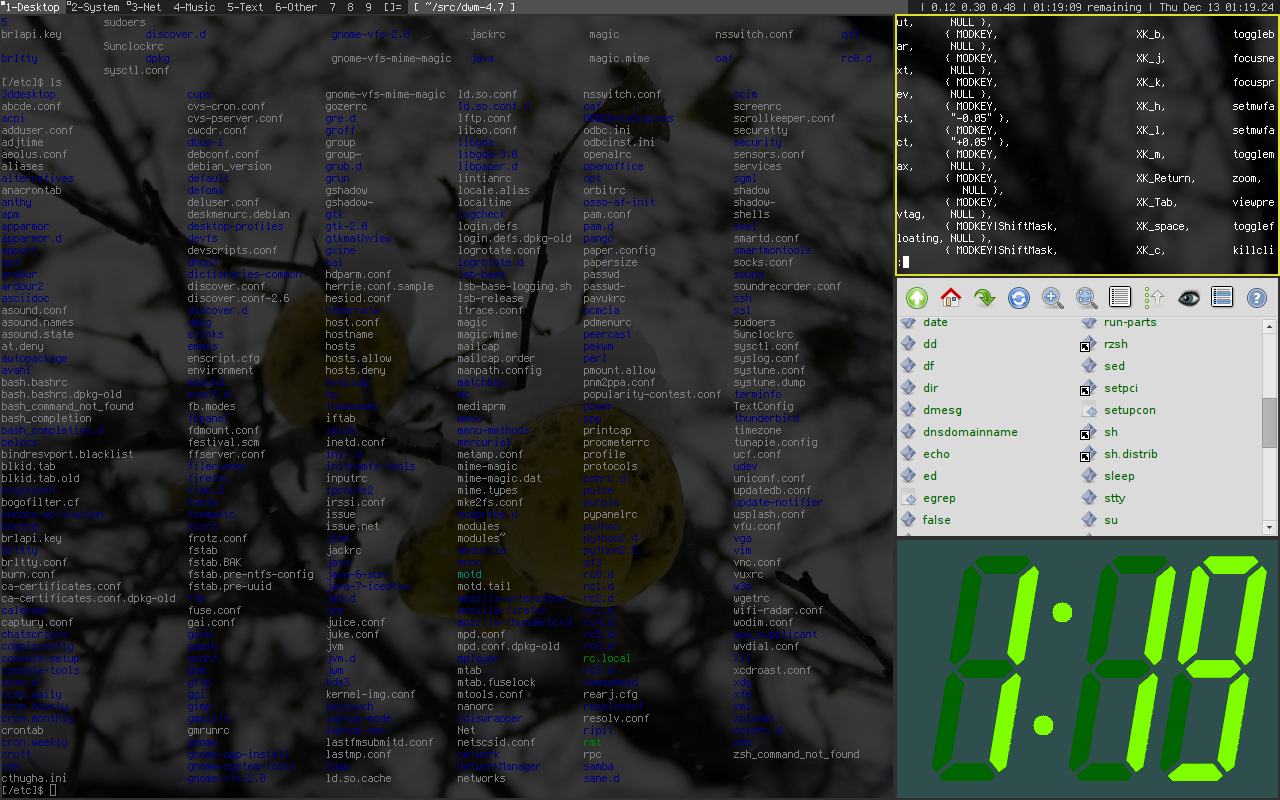

- dwm – allows for switching tiling layouts by clicking a textual ascii art 'icon' in the status bar. The default is a main area + stacking area arrangement, represented by a []= character glyph. Other standard layouts are a single-window "monocle" mode represented by an M and a non-tiling floating layout that permits windows to be moved and resized, represented by a fish-like ><>. Third party patches exist to add a golden section-based Fibonacci layout, horizontal and vertical row-based tiling, or a grid layout. The keyboard-driven menu utility "dmenu", developed for use with dwm,[19] is used with other tiling WMs such as xmonad,[20] and sometimes also with other "light-weight" software like Openbox[19] and uzbl.[21]

- EXWM — EXWM (Emacs X Window Manager) is a full-featured tiling X window manager for Emacs built on top of XELB. It features fully keyboard-driven operations, hybrid layout modes (tiling & stacking), dynamic workspace support, ICCCM/EWMH compliance, RandR (multi-monitor) support, and a built-in system tray.[22]

- herbstluftwm – a manual tiling window manager (similar to i3 or Sway) that uses the concept of monitor independent tags as workspaces. Exactly one tag can be viewed on a monitor, with each tag containing its own layout. Like i3 and Sway, herbstluftwm is configured at runtime via IPC calls from herbstclient.[23]

- fvwm

- musca – Dynamic window manager with influences from Ratpoison and DWM.[24][25]

- i3 – a built-from-scratch window manager, based on wmii. It has vi-like keybindings, and treats extra monitors as extra workspaces, meaning that windows can be moved between monitors easily. Allows vertical and horizontal splits, tabbed and stacked layouts, and parent containers. It can be controlled entirely from the keyboard, but a mouse can also be used.

- Ion – combines tiling with a tabbing interface: the display is manually split in non-overlapping regions (frames). Each frame can contain one or more windows. Only one of these windows is visible and fills the entire frame.

- Larswm – implements a form of dynamic tiling: the display is vertically split in two regions (tracks). The left track is filled with a single window. The right track contains all other windows stacked on top of each other.

- LeftWM – a tiling window manager based on theming and supporting large monitors such as ultrawides.[26]

- Notion - a tiling window manager (originally forked from Ion).[27]

- Qtile – a tiling window manager written, configurable, and extensible in Python.[28]

- Ratpoison — A keyboard-driven manually tiling window manager for X, inspired by GNU Screen.

- spectrwm — a dynamic tiling and reparenting window manager for X11. It tries to stay out of the way so that valuable screen real estate can be used for more important content. It strives to be small, compact, and fast. Formerly called "scrotwm" (a pun based on the word "scrotum").[29][non-primary source needed]

- StumpWM – a keyboard driven offshoot of ratpoison supporting multiple displays (e.g. xrandr) that can be customized on the fly in Common Lisp. It uses Emacs-compatible keybindings by default.

- wmii (window manager improved 2) supports tiling and stacking window management with extended keyboard, mouse, and filesystem based remote control,[30] replacing the workspace paradigm with a new tagging approach.[31] The default configuration uses keystrokes derived from those of the vi text editor. The window manager offers extensive configuration through a virtual filesystem using the 9P filesystem protocol similar to that offered by Plan 9 from Bell Labs.[30] Every window, tag, and column is represented in the virtual filesystem, and windows are controlled by manipulating their file objects (in fact, the configuration file is just a script interfacing the virtual files). This RPC system allows many different configuration styles, including those provided in the base distribution in plan9port and Bourne shell. The latest release 3.9 also includes configurations in Python and Ruby.[32] The latest release supports Xinerama, shipping with its own keyboard-based menu program called wimenu, featuring history and programmable completion.[32][33][34][35]

- xmonad – an extensible WM written in Haskell, which was both influenced by and has since influenced dwm.

Wayland

[edit]Wayland is a new windowing system that aims to replace the X Window System. Only a few tiling managers support Wayland natively.

List of tiling window managers for Wayland

[edit]- Hyprland — Hyprland is a dynamic tiling wayland compositor that offers unique features like smooth animations, dynamic tiling, and rounded corners.

- japokwm — Dynamic Wayland tiling compositor based around creating layouts, based on wlroots.

- newm — Wayland compositor written with laptops and touchpads in mind (currently unmaintained).

- niri — A scrollable-tiling Wayland compositor.

- Velox — Simple window manager based on swc, inspired by dwm and xmonad.

- Vivarium — A dynamic tiling Wayland compositor using wlroots, with desktop semantics inspired by xmonad.

- Sway — Sway is "a drop-in replacement for the i3 window manager, but for Wayland instead of X11. It works with your existing i3 configuration and supports most of i3's features, and a few extras".[36]

- River - River is a dynamic tiling Wayland compositor with flexible runtime configuration, it is maintained and under regular updates.

- CageBreak is a tiling compositor for wayland, based on cage and inspired by Ratpoison, which is easily controlled through the keyboard and a unix domain socket.

- dwl - dwl is a wayland compositor, that was intended to fill the same space in the Wayland world that dwm does in X11. Like dwm, it is written in C, has a small codebase and lacks any configuration interface besides editing the source code.

Others

[edit]- The Oberon operating and programming system, from ETH Zurich includes a tiling window manager.

- The Acme programmer's editor / windowing system / shell program in Plan 9 is a tiling window manager.

- The Samsung Galaxy S3, S4, Note II, and Note 3 smartphones, running a custom variant of Android 4, have a multi-window feature that allows the user to tile two apps on the device's screen. This feature was integrated into stock Android as of version 7.0 "Nougat".

- The Pop Shell extension, from Pop! OS can add tiling windows manager functionalities to GNOME.

- The Amethyst window manager by ianyh, which provides window tiling for macOS and was inspired by xmonad.

- The yabai window manager that for macOS was inspired by bspwm.

- On macOS, Moom, from longstanding Mac developers Many Tricks, is an actively updated window tiling manager.

Tiling applications

[edit]

Although tiling is not the default mode of window managers on any widely used platform, most applications already display multiple functions internally in a similar manner. Examples include email clients, IDEs, web browsers, and contextual help in Microsoft Office. The main windows of these applications are divided into "panes" for the various displays. The panes are usually separated by a draggable divider to allow resizing. Paned windows are a common way to implement a master–detail interface.

Developed since the 1970s, the Emacs text editor contains one of the earliest implementations of tiling. In addition, HTML frames can be seen as a markup language-based implementation of tiling. The tiling window manager extends this usefulness beyond multiple functions within an application, to multiple applications within a desktop. The tabbed document interface can be a useful adjunct to tiling, as it avoids having multiple window tiles on screen for the same function.

See also

[edit]- Integrated development environment style interface

- Split screen (computer graphics)

References

[edit]- ^ "Xerox Star". Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ^ "Ten Years of Window Systems — A Retrospective View". Archived from the original on 2010-03-16. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ "Tiling Window Managers". mnemonikk.org.

- ^ "video". Archived from the original on 2010-12-22. Retrieved 2010-12-22.

- ^ "The First Tiling Window Manager - Siemens RTL Tiled Window Manager (released in 1988)". YouTube. 9 June 2019. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21.

- ^ "Apple Announces OS X El Capitan with Refined Experience & Improved Performance". Apple Newsroom.

- ^ "Build: More Details On Building Windows 8 Metro Apps". PCMAG. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ Leonhard, Woody (2015-11-12). "Review: New Windows 10 version still can't beat Windows 7". InfoWorld. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ "bug.n – Tiling Window Manager for Windows". GitHub. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- ^ "MaxTo - The window manager you didn't know you missed]". Archived from the original on 2018-11-13. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- ^ "Stack WM: Windows Store". Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2017-12-10. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- ^ "Stack on Lost Tech LLC website". Archived from the original on 2018-01-11. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- ^ "Palatial Software Website". 2019-01-10. Retrieved 2019-01-10.

- ^ Button, Rick. "workspacer". workspacer.org. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- ^ Tanner, Marc André. "dwm-win32 - X11 dwm(1) for Windows". brain-dump.org. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- ^ (in German) Falko Benthin (Dec 2008) Herr der Fenster. Schlanker Windowmanager Awesome, alt. link, LinuxUser

- ^ Awesome window manager homepage

- ^ "Baskerville/BSPWM". GitHub.

- ^ a b Arch Linux Magazine Team (January 2010). "Software Review: 2009 LnF Awards". Arch Linux Magazine. Archived from the original on 2010-02-16. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "100 open source gems - part 2". TuxRadar. Future Publishing. 21 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-01-06. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- ^ Vervloesem, Koen (15 July 2009). "Uzbl: a browser following the UNIX philosophy". LWN.net. Eklektix, Inc. Archived from the original on 2009-11-30. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- ^ "Emacs-exwm/Exwm". GitHub.

- ^ "herbstluftwm". herbstluftwm.org. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- ^ "Musca in Launchpad". 26 February 2009.

- ^ "Enticeing/Musca". GitHub.

- ^ GitHub - leftwm/leftwm: LeftWM: A tiling window manager for Adventurers., leftwm, 2019-04-04, retrieved 2019-04-05

- ^ https://notionwm.net

- ^ Verna, Clément (27 September 2018). "5 cool tiling window managers". Fedora Magazine. Qtile. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ "rename scrotwm to spectrwm". github.com. 2012-02-15. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- ^ a b "wmii - Window Manager Improved 2". Wmii.suckless.org. Archived from the original on 2011-12-31. Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- ^ Komis, Antonis (April 2013). "Windows Migration: Desktop Environments & Window Managers". PCLinuxOS. Tiling and Dynamic Tiling Window Managers - wmii. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016.

- ^ a b "suckless.org git repositories". Hg.suckless.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- ^ "Light and speedy. WMI and the reincarnation of the keyboard" (PDF). Linux Magazine. No. 54. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2012.

- ^ Golde, Nico (March 2006). "No wimps. A look at the Wmii Window Manager" (PDF). Linux Magazine. No. 64. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-10-28. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- ^ Saunders, Mike (March 2008). "Lightweight window managers". Linux Format. No. 103. wmii.

- ^ "SwayWM". Archived from the original on 2017-10-10. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

External links

[edit]Tiling window manager

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and principles

A tiling window manager (TWM) is a type of window manager that arranges and resizes application windows to fill the available screen space without overlap—typically automatically in dynamic variants or under user control in manual ones—thereby optimizing the utilization of display real estate in multi-tasking scenarios.[11] This approach contrasts with traditional stacking window managers, where windows can overlap and require manual positioning.[2] TWMs are categorized as dynamic, which automatically manage layouts, or manual, which emphasize user-specified arrangements, both ensuring non-overlapping tiles.[12] The core principles of TWMs revolve around non-overlapping placement, where each window occupies a distinct region of the screen, and resizing, which adjusts window dimensions in response to user commands, focus changes, or the addition of new windows.[13] TWMs also commonly support multiple workspaces or virtual desktops, allowing users to organize windows across separate, switchable screen views to manage complex workflows efficiently.[11] These principles stem from early efforts to enhance productivity in computing environments by minimizing wasted space and reducing the cognitive load of manual window arrangement. In operation, TWMs employ a basic workflow where windows are organized into predefined tiling layouts, such as stacks, grids, or tree-based structures, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the screen.[13] In dynamic TWMs, when a new window opens, it inserts into the current layout, prompting the system to resize and reposition existing windows accordingly; manual TWMs require user commands to direct the insertion and resizing, often via keyboard-driven controls for precise placement.[11] This process promotes predictability and keyboard-centric interaction, making TWMs particularly suited for power users in resource-constrained or high-density display setups.[2]Comparison to stacking window managers

Stacking window managers, also referred to as floating window managers, enable windows to overlap one another, with users manually controlling their position, size, and layering through direct manipulation, often via mouse input. This approach mirrors the traditional desktop metaphor prevalent in major operating systems such as Microsoft Windows and macOS, where windows can be dragged, resized, and stacked to create visual layers.[14] In contrast, tiling window managers arrange windows in non-overlapping layouts that fill the available screen space, either automatically (dynamic) or via user commands (manual), enforcing a structured division of the display into tiles or regions.[12] This fundamental difference in space management ensures maximal utilization of screen real estate in tiling systems, avoiding the wasted space and visual occlusion common in stacking managers where overlapping windows obscure content and lead to desktop clutter. Research from the 1980s demonstrated that tiled arrangements can yield faster task performance for certain users and activities compared to overlapping setups, challenging the prevailing assumption that stacking is inherently superior.[15] User interaction further diverges between the two paradigms: stacking window managers emphasize mouse-driven operations for precise placement and resizing, offering flexibility for visual tasks but potentially increasing cognitive load from manual adjustments. Tiling window managers, by comparison, prioritize keyboard shortcuts and commands for layout changes, promoting a more efficient, hands-on-keyboard workflow that reduces reliance on the mouse and fosters minimalism, though it may feel restrictive for users accustomed to freeform positioning. Modern analyses highlight how stacking can result in "messy defaults" requiring constant user intervention to manage overlaps, while tiling prevents such issues by design but risks allocating disproportionate space to windows that do not align with application content needs, such as chat interfaces.[2] Hybrid window managers address these trade-offs by incorporating both modes, allowing users to switch between non-overlapping tiling for organized multitasking and floating stacking for specific windows requiring overlap or custom sizing, thereby combining the efficiency of tiling with the versatility of stacking.[2]History

Early concepts and Xerox PARC

The foundational ideas for tiling window managers emerged in the late 1960s through research on space-efficient interfaces for handling multiple tasks simultaneously. Douglas Engelbart's oN-Line System (NLS), developed at the Stanford Research Institute, pioneered this with a demonstration in December 1968—known as the "Mother of All Demos"—that showcased multiple tiled windows on a graphical display, allowing users to manipulate text, graphics, and views without overlap to enhance productivity in collaborative computing environments. In the 1970s, Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) built upon these concepts, creating the Alto system in 1973 as the first personal workstation with a bitmapped graphical user interface, incorporating windows, a mouse, and ethernet networking to support interactive computing.[16] The Alto's software environment emphasized efficient display of multiple information views, influencing early window-based interactions, though its implementations like Smalltalk often featured overlapping windows for flexibility.[17] Prominent contributors at PARC included Butler Lampson, who co-led the Alto's design and focused on its hardware-software integration for personal computing, and Charles Simonyi, who collaborated with Lampson on Bravo—the Alto's innovative WYSIWYG text editor that used dedicated windows for editing and formatting documents.[18] These efforts prioritized non-overlapping arrangements in certain applications to maximize screen real estate and streamline user workflows. A key advancement came with the Xerox Star workstation in 1981, designed specifically for office productivity, which adopted tiled, non-overlapping windows as the default for application views to eliminate the need for constant resizing and to prevent visual clutter, observations from user testing showing that people rarely overlapped them anyway. While dialogs and property sheets could overlap, the core desktop layout tiled windows automatically, promoting a structured, overlap-free interface that aligned with PARC's vision of intuitive office automation. PARC's innovations, including the 1982 Cedar environment with its tiled window manager for automatic non-overlapping arrangements, directly inspired wider GUI advancements by demonstrating scalable methods for window organization that balanced efficiency and usability.[19]Evolution in Unix-like systems

The development of tiling window managers in Unix-like systems closely paralleled the maturation of the X Window System, initially released in 1984 at MIT as a network-transparent windowing protocol for bitmap displays on Unix workstations. This foundation enabled the creation of graphical interfaces that addressed the limitations of text-based terminals prevalent in 1980s Unix environments, where screen real estate was scarce and efficiency was critical for multitasking. Early window managers like twm (Tab Window Manager), started in 1987 and standardized in X11R4 by 1989, primarily supported stacking layouts but highlighted the need for structured window arrangements to optimize display usage.[20][21] A pivotal advancement came in 1988 with the release of the Siemens RTL tiled window manager for X11, the first implementation to incorporate automatic tiling strategies. Developed by Siemens, RTL dynamically adjusted window sizes and positions to resolve conflicts over screen space, using algorithms that prioritized visibility and balanced demands from multiple applications—features demonstrated in its handling of tiled layouts without user intervention for resizing. This commercial effort influenced subsequent Unix windowing designs by demonstrating practical automation in resource-limited settings.[22][23] Academic initiatives in the 1980s further advanced tiling concepts within Unix ecosystems. At Carnegie Mellon University, the Andrew Project—a collaboration with IBM initiated in 1982—produced the Andrew Window Manager, which employed strictly tiled, non-overlapping windows to facilitate remote display and shared computing across networked workstations. This system divided the screen into fixed panes for applications, enhancing productivity in distributed Unix setups and serving as a model for non-intrusive window organization.[24] By the 1990s, open-source efforts in Unix window management began incorporating tiling-inspired features, building on terminal multiplexer tools like GNU Screen (first released in 1993) that enabled efficient text-based workspace division. Enlightenment, an open-source window manager debuted in 1997, emphasized lightweight customization and visual effects for X11, laying groundwork for hybrid layouts that evolved toward tiling in later iterations. Ratpoison, emerging in 2000 with conceptual roots in 1990s multiplexer paradigms, represented a minimalist open-source tiling window manager that eschewed decorations and mouse reliance, enforcing keyboard-driven tiling to mimic terminal efficiency on graphical desktops.[25] These milestones reflected a broader shift in Unix-like systems from floating, user-managed windows to automated tiling paradigms, motivated by the demands of low-resource hardware and the prevalence of terminal-centric workflows where overlapping interfaces hindered visibility and focus.[26]Modern developments

In the 2000s, tiling window managers saw increased adoption in Linux communities, driven by a desire for efficient, automated screen management among developers and power users.[27] xmonad, released in 2007, pioneered dynamic tiling through its Haskell-based implementation, enabling extensible layout algorithms and automatic window arrangement without overlaps or gaps.[5] This approach influenced subsequent designs by emphasizing stability and minimal codebases, around 2000 lines.[5] i3, launched in 2009, further popularized the paradigm with its keyboard-centric controls and plain-text configuration, making it accessible for customization while prioritizing manual tiling modes.[4] The 2010s and 2020s marked a transition toward Wayland compatibility, addressing limitations of the aging X11 protocol.[28] Sway, introduced in 2016 as a Wayland-native compositor, served as a drop-in replacement for i3, retaining its configuration syntax while adding support for modern protocols like wlroots.[8] As of June 2025, Sway version 1.11 incorporated enhanced screen capture, output handling, and wlroots 0.19 integration for broader hardware compatibility.[29] Concurrently, tiling features integrated into major desktops via extensions, such as GNOME's Tiling Shell, which extends the shell's layout system with automatic tiling, multi-monitor support, and keyboard-driven snapping inspired by Windows 11.[30] In KDE Plasma, Krohnkite emerged as a dynamic tiling script for KWin, drawing from dwm's principles to enable rock-solid, hybrid floating-tiling workflows.[31] This era also reflected a broader embrace of minimalism in developer environments, where tiling reduced mouse dependency and optimized workflows on high-resolution displays.[32] As of 2025, experimental efforts extended tiling to mobile platforms, particularly through custom Android ROMs and Linux-based UIs. Sxmo, a lightweight interface for devices like the PinePhone, leverages tiling window managers such as Sway or dwm to manage sparse screen real estate via menu-driven and gesture-based controls.[33] In commercial spaces, Microsoft revived tiling concepts with PowerToys' FancyZones, first introduced in 2020 and enhanced through the decade with features like custom grid/canvas layouts, keyboard snapping, and multi-zone support for complex productivity setups.[34]Core concepts and features

Tiling layouts and algorithms

Tiling window managers employ various layouts to arrange windows non-overlappingly across the screen, optimizing space utilization and accessibility. Common layout types include the master-stack model, where one primary window occupies a dedicated master area—typically the larger portion on one side—and the remaining windows are stacked vertically or horizontally in the adjacent stacking area; grid layouts, which divide the screen into a uniform matrix of equal-sized cells; and monocle layouts, which maximize a single window to fill the entire screen while hiding others. These layouts ensure that every window remains fully visible without overlap, contrasting with stacking managers that allow partial occlusion.[7][35] The algorithms underlying these layouts often rely on dynamic insertion rules, where new windows are placed by splitting the currently focused region proportionally according to predefined ratios. In the master-stack model, for instance, the initial window claims the master area, and subsequent windows are added to the stack, resizing existing ones to maintain balance; the split can be horizontal or vertical, with the master typically allocated a fixed fraction like 50-70% of the screen width. Tree-based representations further structure this process, modeling the screen as a hierarchical tree where each node denotes a rectangular region, and leaves represent windows. Binary space partitioning (BSP) trees exemplify this approach, recursively subdividing space with axis-aligned splits: each internal node partitions its parent's rectangle into two child regions, either horizontally or vertically, until leaves hold individual windows. This enables asymmetric arrangements, as splits can follow the longest dimension or alternate directions for balanced growth.[35][36][36] Specific algorithms enhance aesthetic and functional balance, such as those using the golden ratio for splits to approximate natural proportions. The golden ratio, defined as , dictates that new windows occupy a fraction of the parent region's area, with the remainder for the existing content; this creates a Fibonacci-like spiral or dwindle pattern, where windows diminish in size progressively, with each subsequent window taking approximately 0.618 of the remaining space and alternating split directions. Such methods, often implemented via extensible scripting, allow layouts to adapt dynamically to window counts and focus changes. Constraint-based algorithms provide another foundation, where user-defined relations (e.g., relative sizes or alignments) propagate through the layout via a constraint satisfaction solver, ensuring consistent tiling without manual repositioning. These techniques collectively form the core of tiling efficiency, prioritizing algorithmic precision over manual adjustment.[37]Manual control and automation

Manual control in tiling window managers emphasizes keyboard-driven interactions to efficiently manage window focus, positioning, and layout adjustments without relying on mouse input. Users typically employ modifier key combinations, such as Mod+j or Mod+k, to cycle focus between windows in a manner reminiscent of vi editor navigation, allowing seamless movement through tiled arrangements. Additional shortcuts enable window swaps (e.g., Mod+Enter to exchange the focused window with another) and layout rotations to reorient the tiling pattern, promoting rapid workflow adjustments. Some hybrid implementations incorporate limited mouse support for dragging windows or resizing, blending manual precision with traditional input methods.[38] Automation in these systems operates at varying levels to minimize user intervention while maintaining organized layouts. Upon opening or closing a window, the manager automatically resizes and repositions adjacent tiles to maximize screen utilization, adhering to predefined algorithms that prevent overlaps or wasted space. Rule-based mechanisms further enhance this by designating specific applications—such as dialog boxes or media players—to float independently rather than integrate into the tile grid, based on window properties like class or title. This selective automation balances rigidity with flexibility, ensuring transient elements do not disrupt primary workflows.[39][40] Interaction paradigms in tiling window managers often draw from modal editing concepts, similar to vi, where distinct modes facilitate navigation, selection, and manipulation commands without menu interruptions. Gaps, configurable spacing between tiles and screen edges, improve visual clarity and aesthetics, preventing windows from abutting borders and aiding readability in dense layouts. Some experimental projects in the 2020s have explored voice command support for accessibility, such as the Numen FOSS voice control system (as of 2023), which enables hands-free focus switching and window movements via speech recognition when integrated with tiling window managers like those on Linux.[41][42][43]Customization and scripting

Tiling window managers typically employ text-based configuration files that allow users to define keybindings, layouts, and window rules without recompiling the software. For instance, in the i3 window manager, the configuration file located at~/.config/i3/config uses a simple syntax to map keys, such as bindsym $mod+Shift+c reload for reloading the config or bindsym $mod+h focus left for navigation.[44] These files support comments, includes for modular setups, and modes for context-specific bindings, enabling precise control over behavior. Many implementations, including i3, support hot-reloading, where changes apply immediately via a keybind like $mod+Shift+r to restart in place without disrupting the session.[44]

Scripting extends this customization by integrating programming languages directly into the window manager's logic. Awesome WM, for example, is configured entirely in Lua through the rc.lua file, allowing users to define event hooks for dynamic responses, such as automatically tiling a new terminal window upon launch using signals like client.connect_signal("manage", function(c) ... end). Similarly, xmonad uses Haskell for its xmonad.hs configuration, where users can implement custom layouts or manage hooks—like manageHook = composeAll [ className =? "Firefox" --> doShift "web" ]—to automate actions based on window properties or events.[5] These approaches enable behaviors beyond static configs, such as conditional auto-tiling triggered by application launches.

Advanced customization often involves integrating external components for enhanced functionality. Status bars like Polybar can be seamlessly incorporated with tiling window managers, replacing built-in bars in i3 or bspwm by configuring modules for workspaces, system metrics, and window titles via its INI-style config file.[45] Multi-monitor setups benefit from per-screen configurations, where users specify independent layouts or keybinds for each output, as supported in i3 through directives like exec --no-startup-id xrandr --output HDMI-1 --mode 1920x1080.[44]

In the 2020s, trends toward declarative configurations in modern tiling window managers have gained traction, particularly in implementations written in systems languages for better performance and safety. LeftWM, a Rust-based tiling window manager for X11, exemplifies this with its TOML configuration file that declaratively defines themes, layouts, and behaviors without runtime scripting, promoting reproducibility and ease of version control.[46] This shift contrasts with earlier imperative styles, facilitating more maintainable setups in dynamic environments like Wayland compositors.