Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass. They are generally fixed in place in an array to cover roofs, floors, walls, edges, or other objects such as tabletops. Alternatively, tile can sometimes refer to similar units made from lightweight materials such as perlite, wood, and mineral wool, typically used for wall and ceiling applications. In another sense, a tile is a construction tile or similar object, such as rectangular counters used in playing games (see tile-based game). The word is derived from the French word tuile, which is, in turn, from the Latin word tegula, meaning a roof tile composed of fired clay.

Tiles are often used to form wall and floor coverings, and can range from simple square tiles to complex or mosaics. Tiles are most often made of ceramic, typically glazed for internal uses and unglazed for roofing, but other materials are also commonly used, such as glass, cork, concrete and other composite materials, and stone. Tiling stone is typically marble, onyx, granite or slate. Thinner tiles can be used on walls than on floors, which require more durable surfaces that will resist impacts.

Global production of ceramic tiles, excluding roof tiles, was estimated to be 12.7 billion m2 in 2019.[1]

Decorative tile work and colored brick

[edit]

Decorative tilework or tile art should be distinguished from mosaic, where forms are made of great numbers of tiny irregularly positioned tesserae, each of a single color, usually of glass or sometimes ceramic or stone. There are various tile patterns, such as herringbone, staggered, offset, grid, stacked, pinwheel, parquet de Versailles, basket weave, tiles Art, diagonal, chevron, and encaustic which can range in size, shape, thickness, and color.[2]

History

[edit]There are several other types of traditional tiles that remain in manufacture, for example the small, almost mosaic, brightly colored zellij tiles of Morocco and the surrounding countries.

Ancient Middle East

[edit]The earliest evidence of glazed brick is the discovery of glazed bricks in the Elamite Temple at Chogha Zanbil, dated to the 13th century BC. Glazed and colored bricks were used to make low reliefs in Ancient Mesopotamia, most famously the Ishtar Gate of Babylon (c. 575 BC), now partly reconstructed in Berlin, with sections elsewhere. Mesopotamian craftsmen were imported for the palaces of the Persian Empire such as Persepolis.

The use of sun-dried bricks or adobe was the main method of building in Mesopotamia where river mud was found in abundance along the Tigris and Euphrates. Here the scarcity of stone may have been an incentive to develop the technology of making kiln-fired bricks to use as an alternative. To strengthen walls made from sun-dried bricks, fired bricks began to be used as an outer protective skin for more important buildings like temples, palaces, city walls, and gates. Making fired bricks is an advanced pottery technique. Fired bricks are solid masses of clay heated in kilns to temperatures of between 950° and 1,150°C, and a well-made fired brick is an extremely durable object. Like sun-dried bricks, they were made in wooden molds but for bricks with relief decorations, special molds had to be made.

Ancient Indian subcontinent

[edit]Rooms with tiled floors made of clay decorated with geometric circular patterns have been discovered from the ancient remains of Kalibangan, Balakot and Ahladino.[3][4]

Tiling was used in the second century by the Sinhalese kings of ancient Sri Lanka, using smoothed and polished stone laid on floors and in swimming pools. The techniques and tools for tiling is advanced, evidenced by the fine workmanship and close fit of the tiles. Such tiling can be seen in Ruwanwelisaya and Kuttam Pokuna in the city of Anuradhapura. The nine-storied Lovamahapaya (3rd century BC) had copper roof tiles.[5] The roofs were tiled, with red, white, yellow, turquoise and brown tiles. There were also tiles made of bronze. Sigiriya also had an elaborate gatehouse made of timber and brick masonry with multiple tiled roofs. The massive timber doorposts remaining today indicate this.

Ancient Iran

[edit]The Achaemenid Empire decorated buildings with glazed brick tiles, including Darius the Great's palace at Susa, and buildings at Persepolis.[6] The succeeding Sassanid Empire used tiles patterned with geometric designs, flowers, plants, birds and human beings, glazed up to a centimeter thick.[6]

-

Relief made with glazed brick tiles, from the Achaemenid decoration of Palace of Darius in Susa.

Islamic world

[edit]Iran and Central Asia

[edit]

Early Islamic mosaics in Iran consisted mainly of geometric decorations in mosques and mausoleums, made of glazed brick. Distinctive turquoise tiling became popular in the 10th-11th century and was used mostly for Kufic inscriptions on mosque walls. Seyyed Mosque in Isfahan (AD 1122), Dome of Maraqeh (AD 1147) and the Jame Mosque of Gonabad (1212 AD) are among the finest examples.[6] The dome of Jame' Atiq Mosque of Qazvin is also dated to this period.

Beginning in the 11th and 12th centuries, an important technique in making patterns emerged in the form of girih tiling, which used intersecting girih straps to create complex patterns of polygons and stars.

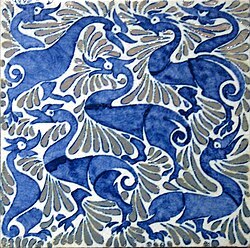

From the 13th century onwards, decorative motifs derived from Chinese arts and textiles appeared in Persian tilework. Used alongside pre-existing geometric patterns and arabesques, new tile designs were based on floral, animal, and mythological icons from the Far East, including lotuses, dianthuses, cloud motifs, phoenixes, and dragons.[7]

The golden age of Persian tilework began during the Timurid Empire. In the mo'araq technique, single-color tiles were cut into small geometric pieces and assembled by pouring liquid plaster between them. After hardening, these panels were assembled on the walls of buildings. But the mosaic was not limited to flat areas. Tiles were used to cover both the interior and exterior surfaces of domes. Prominent Timurid examples of this technique include the Jame Mosque of Yazd (AD 1324–1365), Goharshad Mosque (AD 1418), the Madrassa of Khan in Shiraz (AD 1615), and the Molana Mosque (AD 1444).[6] Islamic buildings in Samarkand and Bukhara in central Asia also exhibited very sophisticated floral ornamentation.

Mihrabs, being the focal points of mosques, were usually the places where most sophisticated tilework was placed. The 14th-century mihrab at Madrasa Imami in Isfahan is an outstanding example of aesthetic union between the Islamic calligrapher's art and abstract ornament. The pointed arch, framing the mihrab's niche, bears an inscription in Kufic script used in 9th-century Qur'an.[8]

During the Safavid period, mosaic tiling was often replaced by a technique known as Haft-rang ('seven colors'), a form of cuerda seca. Pictures were painted on plain rectangle tiles, glazed and fired afterwards. Besides economic reasons, the seven colors method gave more freedom to artists and was less time-consuming. It was popular through the Qajar period, when the palette of colors was extended by yellow and orange.[6] The seven colors of Haft Rang tiles were usually black, white, ultramarine, turquoise, red, yellow and fawn.

One of the best known architectural masterpieces of Safavid Iran is the 17th century Shah Mosque in Isfahan. Its dome is a prime example of tile mosaic and its winter praying hall houses one of the finest ensembles of cuerda seca tiles in the world. A wide variety of tiles had to be manufactured in order to cover the complex forms of the hall with consistent Haft Rang patterns. The result was a technological triumph as well as a dazzling display of abstract ornament.[8]

Turkey

[edit]Persianate tile traditions continued and spread to much of the Islamic world, notably the İznik pottery of Turkey under the Ottoman Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries. Palaces, public buildings, mosques and türbe mausoleums were heavily decorated with large brightly colored patterns, typically with floral motifs, and friezes of astonishing complexity, including floral motifs and calligraphy as well as geometric patterns.

-

Enderun library, Topkapi Palace

-

Window Apartments of the Crown Prince, Topkapi Palace

South Asia

[edit]In South Asia monuments and shrines adorned with Kashi tile work from Persia became a distinct feature of the shrines of Multan and Sindh. The Wazir Khan Mosque in Lahore stands out as one of the masterpieces of Kashi time work from the Mughal period.

North Africa

[edit]The zellige tradition of Arabic North Africa uses small colored tiles of various shapes to make very complex geometric patterns. It is halfway to mosaic, but as the different shapes must be fitted precisely together, it falls under tiling. The use of small coloured glass fields also make it rather like enamelling, but with ceramic rather than metal as the support.

Europe

[edit]

Medieval Europe made considerable use of painted tiles, sometimes producing very elaborate schemes, of which few have survived. Religious and secular stories were depicted. The imaginary tiles with Old Testament scenes shown on the floor in Jan van Eyck's 1434 Annunciation in Washington are an example. The 14th century "Tring tiles" in the British Museum show childhood scenes from the Life of Christ, possibly for a wall rather than a floor,[9] while their 13th century "Chertsey Tiles", though from an abbey, show scenes of Richard the Lionheart battling with Saladin in very high-quality work.[10] Medieval letter tiles were used to create Christian inscriptions on church floors.

Medieval influences between Middle Eastern tilework and tilework in Europe were mainly through Islamic Iberia and the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires. The Alhambra zellige are said to have inspired the tessellations of M. C. Escher.[citation needed] Medieval encaustic tiles were made of multiple colours of clay, shaped and baked together to form a pattern that, rather than sitting on the surface, ran right through the thickness of the tile, and thus would not wear away.

Azulejos are derived from zellij, and the name is likewise derived. The term is both a simple Portuguese and Spanish term for zellige, and a term for later tilework following the tradition. Some azujelos are small-scale geometric patterns or vegetative motifs, some are blue monochrome and highly pictorial, and some are neither. The Baroque period produced extremely large painted scenes on tiles, usually in blue and white, for walls. Azulejos were also used in Latin American architecture.

-

Quadra (architecture) of St. John the Baptist covered with azulejos in carpet style (17th c.); Museu da Reinha D. Leonor; Beja, Portugal.

-

The Battle of Buçaco, depicted in azulejos.

-

Azulejo scenes in Portugal

Delftware wall tiles, typically with a painted design covering only one (rather small) blue and white tile, were ubiquitous in Holland and widely exported over Northern Europe from the 16th century on, replacing many local industries. Several 18th century royal palaces had porcelain rooms with the walls entirely covered in porcelain in tiles or panels. Surviving examples include ones at Capodimonte, Naples, the Royal Palace of Madrid and the nearby Royal Palace of Aranjuez.

The Victorian period saw a great revival in tilework, largely as part of the Gothic Revival, but also the Arts and Crafts Movement. Patterned tiles, or tiles making up patterns, were now mass-produced by machine and reliably level for floors and cheap to produce, especially for churches, schools and public buildings, but also for domestic hallways and bathrooms. For many uses the tougher encaustic tile was used. Wall tiles in various styles also revived; the rise of the bathroom contributing greatly to this, as well as greater appreciation of the benefit of hygiene in kitchens. William De Morgan was the leading English designer working in tiles, strongly influenced by Islamic designs.

Since the Victorian period tiles have remained standard for kitchens and bathrooms, and many types of public area.

Panot is a type of outdoor cement tile and the associated paving style, both found in Barcelona. In 2010, around 5,000,000 m2 (54,000,000 sq ft) of Barcelona streets were panot-tiled.[11]

Portugal and São Luís continue their tradition of azulejo tilework today, with tiles used to decorate buildings, ships,[12] and even rocks.

Far East

[edit]Decorated tiles or glazed bricks feature in East Asian ceramics in the form of Chinese glazed roof tiles and in palatial and temple architecture such as Nine-Dragon Walls and the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing.

In 17th century during the colonialization of Spain in the Philippines, they introduced the Baldozas Mosaicos to describe the Mediterranean cement tiles, but they are now more commonly referred to as Machuca tiles during the 19th AD, named after Don Pepe, the son of the renowned producer of Baldozas Mosaicos in the Philippines, Don Jose Machuca by Romero.

Roof tiles

[edit]

Roof tiles are overlapping tiles designed mainly to keep out precipitation such as rain or snow, and are traditionally made from locally available materials such as clay or slate. Later tiles have been made from materials such as concrete, and plastic.

Roof tiles can be affixed by screws or nails, but in some cases historic designs such as Marseilles tiles utilize interlocking systems that can be self-supporting. Tiles typically cover an underlayment system, which seals the roof against water intrusion.[13]

Clay roof tiles historically gained their color purely from the clay that they were composed of, resulting in largely red, orange, and tan colored roofs. Over time some cultures, notably in Asia, began to apply glazes to clay tiles, achieving a wide variety of colors and combinations. Modern clay roof tiles typically source their color from kiln firing conditions, the application of glaze, or the use of a ceramic engobe.[14] Contrary to popular belief a glaze does not weatherproof a tile, the porosity of the clay body is what determines how well a tile will survive harsh weather conditions.[15]

Floor tiles

[edit]

Floor tiles are commonly made of ceramic or stone, although recent technological advances have resulted in rubber or glass tiles for floors as well. Ceramic tiles may be painted and glazed. Small mosaic tiles may be laid in various patterns. Floor tiles are typically set into mortar consisting of sand, Portland cement and often a latex additive. The spaces between the tiles are commonly filled with sanded or unsanded floor grout, but traditionally mortar was used.

Natural stone tiles can be beautiful but as a natural product they are less uniform in color and pattern, and require more planning for use and installation. Mass-produced stone tiles are uniform in width and length. Granite or marble tiles are sawn on both sides and then polished or finished on the top surface so that they have a uniform thickness. Other natural stone tiles such as slate are typically "riven" (split) on the top surface so that the thickness of the tile varies slightly from one spot on the tile to another and from one tile to another. Variations in tile thickness can be handled by adjusting the amount of mortar under each part of the tile, by using wide grout lines that "ramp" between different thicknesses, or by using a cold chisel to knock off high spots.

Some stone tiles such as polished granite, marble, and travertine are very slippery when wet. Stone tiles with a riven surface such as slate or with a sawn and then sandblasted or honed surface will be more slip-resistant. Ceramic tiles for use in wet areas can be made more slip-resistant by using very small tiles so that the grout lines acts as grooves, by imprinting a contour pattern onto the face of the tile, or by adding a non-slip material, such as sand, to the glazed surface.

The hardness of natural stone tiles varies such that some of the softer stone (e.g. limestone) tiles are not suitable for very heavy-traffic floor areas. On the other hand, ceramic tiles typically have a glazed upper surface and when that becomes scratched or pitted the floor looks worn, whereas the same amount of wear on natural stone tiles will not show, or will be less noticeable.

Natural stone tiles can be stained by spilled liquids; they must be sealed and periodically resealed with a sealant in contrast to ceramic tiles which only need their grout lines sealed. However, because of the complex, nonrepeating patterns in natural stone, small amounts of dirt on many natural stone floor tiles do not show.

The tendency of floor tiles to stain depends not only on a sealant being applied, and periodically reapplied, but also on their porosity or how porous the stone is. Slate is an example of a less porous stone while limestone is an example of a more porous stone. Different granites and marbles have different porosities with the less porous ones being more valued and more expensive.

Most vendors of stone tiles emphasize that there will be variation in color and pattern from one batch of tiles to another of the same description and variation within the same batch. Stone floor tiles tend to be heavier than ceramic tiles and somewhat more prone to breakage during shipment.

Rubber floor tiles have a variety of uses, both in residential and commercial settings. They are especially useful in situations where it is desired to have high-traction floors or protection for an easily breakable floor. Some common uses include flooring of garage, workshops, patios, swimming pool decks, sport courts, gyms, and dance floors.

Plastic floor tiles including interlocking floor tiles that can be installed without adhesive or glue are a recent innovation and are suitable for areas subject to heavy traffic, wet areas and floors that are subject to movement, damp or contamination from oil, grease or other substances that may prevent adhesion to the substrate. Common uses include old factory floors, garages, gyms and sports complexes, schools and shops.

Ceiling tiles

[edit]Ceiling tiles are lightweight tiles used inside buildings. They are placed in an aluminium grid; they provide little thermal insulation but are generally designed either to improve the acoustics of a room or to reduce the volume of air being heated or cooled.

Mineral fiber tiles are fabricated from a range of products; wet felt tiles can be manufactured from perlite, mineral wool, and fibers from recycled paper; stone wool tiles are created by combining molten stone and binders which is then spun to create the tile; gypsum tiles are based on the soft mineral and then finished with vinyl, paper or a decorative face.[citation needed]

Ceiling tiles very often have patterns on the front face; these are there in most circumstances to aid with the tiles ability to improve acoustics.[citation needed]

Ceiling tiles also provide a barrier to the spread of smoke and fire. Breaking, displacing, or removing ceiling tiles enables hot gases and smoke from a fire to rise and accumulate above detectors and sprinklers. Doing so delays their activation, enabling fires to grow more rapidly.[16]

Ceiling tiles, especially in old Mediterranean houses, were made of terracotta and were placed on top of the wooden ceiling beams and upon those were placed the roof tiles. They were then plastered or painted, but nowadays are usually left bare for decorative purposes.

Modern-day tile ceilings may be flush mounted (nail up or glue up) or installed as dropped ceilings.

Materials and processes

[edit]Ceramic

[edit]Ceramic materials for tiles include earthenware, stoneware and porcelain.[17] Terracotta is a traditional material used for roof tiles.[18]

Porcelain tiles

[edit]This is a US term, and defined in ASTM standard C242 as a ceramic mosaic tile or paver that is generally made by dust-pressing and of a composition yielding a tile that is dense, fine-grained, and smooth, with sharply-formed face, usually impervious. The colours of such tiles are generally clear and bright.[19]

The ISO 13006 defines a "porcelain tile" as a "fully vitrified tile with water absorption less than or equal to 0.5%, belonging to groups AIa and BIa (of ISO 13006).".[20] The ANSI defines as "a ceramic tile that has 'a water absorption of 0.5%' or less.” It is made generally by the pressed or extruded method."[21]

Pebble

[edit]

Similar to mosaics or other patterned tiles, pebble tiles are tiles made up of small pebbles attached to a backing. The tile is generally designed in an interlocking pattern so that final installations fit of multiple tiles fit together to have a seamless appearance. A relatively new tile design, pebble tiles were originally developed in Indonesia using pebbles found in various locations in the country. Today, pebble tiles feature all types of stones and pebbles from around the world.

Digital printed

[edit]Printing techniques and digital manipulation of art and photography are used in what is known as "custom tile printing". Dye sublimation printers, inkjet printers and ceramic inks and toners permit printing on a variety of tile types yielding photographic-quality reproduction.[22] Using digital image capture via scanning or digital cameras, bitmap/raster images can be prepared in photo editing software programs. Specialized custom-tile printing techniques permit transfer under heat and pressure or the use of high temperature kilns to fuse the picture to the tile substrate. This has become a method of producing custom tile murals for kitchens, showers, and commercial decoration in restaurants, hotels, and corporate lobbies.

[23] Recent technology applied to Digital ceramic and porcelain printers allow images to be printed with a wider color gamut and greater color stability even when fired in a kiln up to 2200 °F.

Diamond etched

[edit]A method for custom tile printing involving a diamond-tipped drill controlled by a computer. Compared with the laser engravings, diamond etching is in almost every circumstance more permanent.[citation needed]

Mathematics of tiling

[edit]

Certain shapes of tiles, most obviously rectangles, can be replicated to cover a surface with no gaps. These shapes are said to tessellate (from the Latin tessella, 'tile') and such a tiling is called a tessellation. Geometric patterns of some Islamic polychrome decorative tilings are rather complicated (see Islamic geometric patterns and, in particular, Girih tiles), even up to supposedly quasiperiodic ones, similar to Penrose tilings.

Further reading

[edit]- Carboni, S. & Masuya, T. (1993). Persian tiles. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Marilyn Y. Goldberg, "Greek Temples and Chinese Roofs," American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 87, No. 3. (Jul. 1983), pp. 305–310

- Örjan Wikander, "Archaic Roof Tiles the First Generations," Hesperia, Vol. 59, No. 1. (Jan.–Mar. 1990), pp. 285–290

- William Rostoker; Elizabeth Gebhard, "The Reproduction of Rooftiles for the Archaic Temple of Poseidon at Isthmia, Greece," Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol. 8, No. 2. (Summer, 1981), pp. 211–227

- Michel Kornmann and CTTB, "Clay bricks and roof tiles, manufacturing and properties", Soc. Industrie Minerale, Paris (2007) ISBN 2-9517765-6-X

- E-book on the manufacture of roofing tiles in the United States from 1910.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ 'World Production And Consumption Of Ceramic Tiles.' Ceramic World Review no. 138. Pg. 40

- ^ "Ceramic Tile History". Traditional Building. 15 September 2020. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Indian History. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. 1926. ISBN 9781259063237.

kalibangan tiles.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576079072.

- ^ The Island (PDF), 18 October 2005

- ^ a b c d e Iran: Visual Arts: history of Iranian Tile Archived 24 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Iran Chamber Society

- ^ Crowe, Yolande (1991). "Late Thirteenth-Century Persian Tilework and Chinese Textiles". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 5: 153–61.

- ^ a b Fred S. Kleiner (2008). Gardner's Art Through The Ages, A Global History. Cengage Learning. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-495-41059-1.

- ^ Tring Tiles Archived 18 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine British Museum

- ^ Chertsey Tiles Archived 18 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, British Museum

- ^ "La verdadera historia del 'panot' de Barcelona". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 11 February 2018. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ^ "Trafaria Praia: On the Waterfront". 23 August 2013. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ "Shingle Tile Installation Manual" (PDF). Ludowici Roof Tile. 2022.

- ^ Worcester, Wolsey Garnett (1910). The Manufacture of Roofing Tile. Springfield, Ohio: Springfield Publishing Company. pp. 27–28, 93–94.

- ^ William Carty; Hyojin Lee (16 August 2017). "Ceramics for Exterior Applications & A Discussion of Heat Transfer and Storage" (PDF). Boston Valley Terra Cotta.

- ^ Missing Ceiling Tiles. Archived 16 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Washington, D.C.: United States Congress Office of Compliance, 2008.

- ^ "What are ceramics?". Science Learning Hub. 27 April 2010. Archived from the original on 27 March 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Maldonado, Eduardo (19 November 2014). Environmentally Friendly Cities: Proceedings of Plea 1998, Passive and Low Energy Architecture, 1998, Lisbon, Portugal, June 1998. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-25622-8. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018.

- ^ Dictionary of Ceramics. A.Dodd. Institute of Materials/Pergamon Press. 1994.

- ^ Griese, Bill. "A world of difference" (PDF). TCNA. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ Kelechava, Brad (8 January 2018). "The Eminence of Porcelain Tile". ANSI. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "Inkjet Decoration of Ceramic Tiles". digitalfire.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ "Next Generation of the Digital Printing Process". picturedtile.com. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

History

Tile was founded in 2013 by Mike Farley, who was inspired by his own experiences with frequently lost items like keys and wallets. The company emerged from the Y Combinator incubator program and quickly raised $2.6 million through a crowdfunding campaign on the Selfstarter platform.[6] This funding supported the development and launch of Tile's first product, the original Tile tracker, in 2014—a small, coin-shaped Bluetooth device designed to attach to items and connect to a companion mobile app for location tracking.[7] The company experienced rapid growth in the emerging market for Bluetooth item trackers. By 2018, Tile had sold over 15 million units and projected $100 million in revenue for that year, with popular models like the Tile Mate becoming best-sellers on platforms such as Amazon.[8] Throughout the late 2010s, Tile expanded its product lineup to include specialized trackers: the slim, card-shaped Tile Slim for wallets in 2015; the rugged Tile Pro with a louder ringer and replaceable battery in 2018; the adhesive Tile Sticker for small items like remotes in 2021; and updated versions of the Tile Mate with improved range and water resistance up to IP67. Batteries in these devices typically last one to three years, with options for replaceable CR2032 cells in some models.[8] In 2021, Tile introduced its first ultra-wideband (UWB) tracker, the Tile Ultra, which offered enhanced precision finding capabilities similar to those in competing products like Apple's AirTag. That same year, Tile partnered with Amazon to integrate with the Sidewalk network, expanding coverage beyond Bluetooth range using Amazon's low-power wide-area network.[9] In November 2021, Life360, a family location-sharing company, acquired Tile for $205 million. The acquisition allowed Tile to operate as an independent subsidiary while benefiting from Life360's infrastructure for improved family safety features, such as integrating trackers with location alerts.[9] Post-acquisition, Tile continued to innovate. By 2024, select models added SOS alerts, enabling users to send the tracker's location to emergency contacts by triple-pressing the device. The company also enhanced its Anti-Theft Mode to prevent unwanted ringing and introduced smart alerts for unusual location changes via the Premium subscription service, priced at $2.99 per month or $29.99 annually as of 2025.[10] Tile addressed privacy concerns, including vulnerabilities in Bluetooth MAC address encryption identified in research from 2021 onward, by implementing Anti-Stalking alerts and policy updates, though it maintained an opt-in crowdsourced network powered by over 40 million devices worldwide. Tile utilizes its own independent crowdsourced network for its trackers, which operates on both iOS and Android devices without relying on Apple or Google networks, enhancing its position as an alternative to big tech tracking solutions.[11] As of November 2025, Tile has integrated with smart home ecosystems and expanded anti-theft measures, solidifying its position in the competitive tracker market alongside products from Apple, Google, and Samsung.[12]Types and Applications

Roof Tiles

Roof tiles are specialized coverings designed for sloped roofs to provide weatherproofing, durability, and aesthetic appeal in architectural structures. These tiles are typically laid in overlapping courses to shed water effectively, with shapes engineered for interlocking and ventilation to prevent moisture accumulation. Common types include flat tiles, which form a simple, uniform surface; pantiles, featuring an S-shaped profile for single-lap installation that enhances water runoff; and interlocking varieties, such as the tegula and imbrex system originating in ancient Greece around the 7th century BCE and adopted by the Romans, where flat tegula tiles cover the roof plane and curved imbrex tiles seal the joints between them.[13][14][15] The evolution of roof tile materials began with fired clay in ancient Rome, valued for its availability and resistance to environmental degradation, and progressed to concrete and composite formulations in the modern era for improved affordability and lighter weight. Specific profiles, like the S-shaped Spanish tiles, were developed for Mediterranean climates to facilitate rapid drainage in heavy rainfall and high humidity, allowing air circulation beneath the tiles to reduce heat buildup. Concrete tiles, introduced widely in the early 20th century, mimic clay's appearance while offering reduced production costs and enhanced impact resistance compared to traditional ceramics.[13][16][17] Installation of roof tiles involves securing overlapping layers to horizontal battens nailed to the roof deck, ensuring a minimum slope gradient of 15-25 degrees for effective drainage and to avoid ponding. Tiles are fixed with clips, hooks, or nails through pre-drilled holes, with the first course at the eaves overhanging to direct water away from the facade. Clay tiles typically weigh 40-50 kg/m² when installed, necessitating structural reinforcement in some designs to support the load without compromising roof integrity.[18][19] Regional variations reflect local environmental challenges and cultural influences, such as Chinese curved eaves tiles, which use lightweight, upturned profiles on wooden frameworks to distribute seismic forces and enhance earthquake resistance through flexible joinery. In colonial architecture, French canal tiles—curved, barrel-like forms—were adapted for tropical climates in the Americas, providing superior ventilation and resistance to humidity while echoing European traditions. These adaptations underscore roof tiles' versatility in balancing protection against wind, rain, and seismic activity across diverse geographies.[20][21] Compared to alternatives like asphalt shingles or metal sheeting, roof tiles offer distinct advantages, including inherent fire resistance due to their non-combustible composition, which prevents ignition and spread during wildfires. Their longevity can reach up to 100 years with proper maintenance, far exceeding many synthetic materials, as evidenced by surviving historic installations. Additionally, roof tiles provide thermal insulation through air spaces and material density, reducing heat transfer into buildings and lowering cooling demands in warm climates.[22][23]Floor and Wall Tiles

Floor and wall tiles serve both functional and aesthetic purposes in interior spaces, providing durable surfaces that resist wear, moisture, and impacts while allowing for customizable designs in residential and commercial settings.[24] These tiles are engineered to meet specific performance criteria, ensuring safety and longevity in high-traffic or humid environments like kitchens, bathrooms, and hallways. In flooring applications, tiles must prioritize slip resistance and structural integrity to prevent accidents and support daily use. Anti-slip ratings, determined by the DIN 51130 standard, range from R10 to R13, where R10 offers moderate resistance suitable for occasional wet areas (friction coefficient 0.2-0.4), and R13 provides high grip for constantly wet or sloped surfaces (friction >0.7).[25] In bathroom settings, matte finishes on anti-slip tiles further enhance safety by providing additional traction in wet conditions.[26] Porcelain floor tiles meet EN 14411 requirements for dynamic load Group I (≥1,500 N breaking strength), suitable for residential and light commercial foot traffic, including heavy furniture when properly installed.[27] Additionally, ceramic and porcelain tiles are highly compatible with underfloor heating systems due to their thermal conductivity, which allows efficient heat transfer without cracking when using flexible adhesives rated for temperature fluctuations up to 50°C.[28] For wall coverings, tiles excel in moisture-prone areas such as bathroom and kitchen backsplashes, where their low porosity prevents water ingress and mold growth. In small bathrooms, light-colored tiles can reflect light to create an illusion of greater space.[29] Porcelain tiles, with water absorption below 0.5%, offer superior moisture resistance compared to standard ceramics, ensuring hygiene and ease of cleaning in splash zones.[30] Historically, Roman opus tessellatum techniques used small tesserae to create intricate mosaic wall and floor designs, influencing modern applications for decorative yet protective surfaces.[31] Tile sizes and formats vary to suit installation needs and visual impact, with standard options like 300x300 mm squares providing versatility for traditional layouts, while large-format slabs up to 120x240 cm minimize seams for seamless, modern aesthetics. In bathrooms, large-format slabs or continuous wall-to-floor tiling reduce grout lines, facilitating easier cleaning by limiting areas where dirt and moisture accumulate.[32][33] Grouting techniques enhance durability and hygiene; epoxy grout, a two-part resin-hardener mix, forms a non-porous seal that resists stains, chemicals, and bacteria, outperforming cement-based alternatives in wet areas.[34] Modern standards, such as ISO 13006, classify tiles by water absorption to guide suitability: porcelain tiles (Group AI) absorb less than 0.5%, qualifying them for exterior or high-moisture interiors, while ceramic tiles (Group BI) range from 0.5% to 3% for general use.[35] Environmental factors like thermal expansion influence design; ceramics have coefficients of 6-8 × 10^{-6} /°C, necessitating joint spacing every 3-4 meters to accommodate expansion and prevent cracking from temperature changes.[36][37]Ceiling and Decorative Tiles

Ceiling tiles serve both functional and ornamental purposes, with suspended mineral fiber types commonly employed in contemporary office settings for their superior acoustic performance. These tiles, typically sized at 600x600mm to fit standard grid systems, offer Noise Reduction Coefficient (NRC) ratings greater than 0.5, such as 0.70 for products like Ultima, allowing them to absorb a significant portion of sound waves and reduce echo in open-plan environments.[38] Historical precedents for decorative ceiling applications include coffered designs in Renaissance palaces, exemplified by the deeply framed panels in Florence's Palazzo Vecchio, which provided structural support while enhancing visual grandeur through painted motifs.[39] Decorative techniques for tiles emphasize artistry and durability, as seen in hand-painted Delft tiles developed in 17th-century Netherlands to surround fireplaces. Crafted from tin-glazed earthenware with cobalt-blue designs depicting biblical scenes, maritime motifs, or floral elements, these tiles resisted heat and soot while transforming utilitarian spaces into focal points of aesthetic interest.[40] Similarly, Victorian encaustic tiles utilized an inlaid clay process to create intricate friezes with heraldic patterns and geometric borders, often in two- to six-color schemes, lending opulent detailing to architectural interiors like those in the Palace of Westminster.[41] Installation approaches vary by application, with drop-ceiling systems relying on suspended metal grids for efficiency. Hanger wires are attached to ceiling joists at intervals of about 1.2 meters, supporting main beams spaced 1.2 meters apart and cross tees to form a level framework, into which tiles are inserted for quick access to utilities.[42] For ornamental mural tiles in Art Deco styles, adhesive methods predominate, involving the application of latex-modified thinset mortar via a 6mm notched trowel directly to the substrate and the tile backs—particularly for irregular handmade pieces—to ensure full contact and longevity.[43] Beyond aesthetics, ceiling tiles incorporate acoustic enhancements through perforations that promote sound diffusion and absorption, thereby shortening reverberation time in enclosed spaces to foster clearer communication and comfort.[44] Safety standards classify these tiles under EN 13501, where A1 ratings indicate fully non-combustible materials producing no smoke or droplets, and A2 denotes limited combustibility with minimal additional fire contribution, critical for compliance in public and commercial buildings.[45] Notable artistic applications highlight tiles' role in cultural expression, such as William Morris's 1860s panels inspired by medieval embroidery, featuring clustered daisy motifs hand-painted in blue and yellow on tin-glazed earthenware to evoke naturalistic flora in domestic settings.[46] In modern contexts, mosaic tile revivals energize public art, as in the interlocking ceramic patterns adorning Westminster Cathedral's chapels or Antoni Gaudí's trencadis technique at Park Güell, where broken tiles form vibrant, undulating landscapes that blend tradition with innovative abstraction.[47]Materials and Manufacturing

Ceramic and Porcelain

Ceramic tiles are primarily composed of clay-based mixtures that undergo high-temperature firing to achieve durability and versatility in construction and decoration. The two main subtypes within ceramics are earthenware and stoneware, distinguished by their firing temperatures and resulting water absorption rates. Earthenware tiles, fired at temperatures between 900°C and 1100°C, exhibit water absorption rates greater than 10%, making them suitable only for dry interior wall applications with limited moisture exposure.[48][49] In contrast, stoneware tiles are fired at higher temperatures ranging from 1100°C to 1300°C, resulting in water absorption of 0.5% to 6%, which enhances their strength and resistance to environmental factors.[48][50][49] Porcelain tiles represent a fully vitrified ceramic variant, achieved through firing at 1200°C to 1400°C using primarily kaolin clay, which contributes to their high density of 2.3 to 2.5 g/cm³ and extremely low porosity under 0.5%.[51][52][53] This vitrification process creates a non-porous, glass-like body that is denser and more impermeable than standard ceramics.[54] The manufacturing process for ceramic and porcelain tiles begins with mixing raw materials, typically comprising about 50% clay, 20% feldspar as a flux, and 30% silica for structural integrity.[53] These ingredients are blended with water to form a slurry, then processed via extrusion for shaped profiles or dry-pressing for flat tiles, where powdered mixtures are compressed under high pressure into molds.[55][56] Following forming, tiles undergo drying to remove moisture, followed by glazing to apply a protective and decorative surface layer. Firing occurs in single or double cycles: single firing combines body and glaze densification in one step at peak temperatures, while double firing involves separate bisque firing for the body and subsequent glost firing for the glaze.[57][58] Key properties of ceramic and porcelain tiles include a Mohs hardness of 6 to 7, providing good scratch resistance for flooring and wall applications.[59] Porcelain variants offer superior frost resistance due to their low water absorption, making them ideal for exterior uses such as roofing where freeze-thaw cycles occur.[60] Abrasion resistance is quantified by PEI ratings from 0 to 5, with higher ratings indicating suitability for high-traffic areas; for instance, PEI 4 or 5 is recommended for commercial floors.[60][61] The development of porcelain marked a significant historical shift, originating in China during the Tang Dynasty around the 7th century CE, where kaolin-based formulas enabled true vitrification.[62] Europeans replicated this in 1710 at the Meissen manufactory in Germany, establishing the first successful production of hard-paste porcelain outside Asia.[63]Natural and Composite Materials

Natural stone tiles, derived directly from quarried materials such as marble, granite, and slate, offer distinctive organic aesthetics characterized by unique veining and textures that reflect their geological origins. Marble tiles, prized for their elegant, flowing veining patterns formed by mineral impurities during metamorphism, exhibit compressive strengths typically ranging from 80 to 150 MPa, while granite provides superior durability with compressive strengths of 100 to 250 MPa, making it suitable for high-traffic applications.[64][65] Slate tiles, with their natural cleft surfaces, deliver compressive strengths around 70 to 120 MPa and are valued for their layered structure that enhances slip resistance.[64] These properties stem from the stones' inherent mineral compositions, including calcite in marble and quartz-feldspar in granite.[66] Pebble tiles consist of aggregates of small river stones, typically 20 to 50 mm in diameter, embedded in a resin matrix to form mosaic-like sheets for flooring and wall applications. Sourced from natural riverbeds, these stones provide a textured, organic surface that promotes gentle foot massage and enhances slip resistance, making them ideal for spa environments, shower floors, and outdoor pathways.[67] The resin binding ensures stability while preserving the pebbles' rounded, water-worn shapes for an earthy aesthetic.[68] Composite tiles, such as terrazzo and engineered quartz, combine natural aggregates with binding agents to achieve enhanced uniformity and performance. Terrazzo tiles incorporate marble or granite chips—often 70% or more by volume—set in a Portland cement matrix, which is then ground and polished to reveal a speckled pattern with compressive strengths exceeding 30 MPa after curing.[69][70] Engineered quartz tiles comprise approximately 90% ground quartz particles bound by 7-10% polyester or epoxy resins, cured under controlled heat (around 85°C) or UV exposure for uniformity and stain resistance, resulting in flexural strengths of 40-50 MPa.[71][72] These composites differ from ceramics by relying on cold-pressing and binding rather than high-temperature firing, yielding more flexible installation options.[70] The processing of natural and composite tiles begins with quarrying, where large blocks of stone are extracted using explosives or wire saws, followed by slab cutting to thicknesses of about 2 cm via diamond-tipped gang saws or water jets to minimize cracking.[73] For pebble and composite tiles, aggregates are sorted and mixed with resins or cement before pressing into molds. Sealing is applied post-cutting using penetrating silicone- or acrylic-based compounds to reduce porosity and protect against moisture absorption, particularly for porous marbles.[74] However, these processes raise sustainability concerns, including high water consumption—up to 3.62 cubic meters per tonne of marble tile production—primarily for cooling saw blades and dust suppression during cutting.[75] Advantages of natural and composite tiles include eco-friendly sourcing options, such as incorporating recycled glass aggregates in resin-bound composites, which reduces landfill waste and virgin material demand by up to 50% in some formulations.[76] Despite their higher upfront costs—often 20-50% more than ceramic alternatives due to labor-intensive quarrying—and weights of 20-30 kg/m² for standard 2 cm tiles, they offer long-term durability and recyclability, minimizing replacement needs over decades.[77][78]Advanced Printing and Etching Techniques

Advanced printing and etching techniques have revolutionized tile customization by enabling high-precision surface modifications that enhance aesthetic versatility and functionality. Digital inkjet printing, introduced in the ceramic tile industry during the early 2000s, applies layers of ceramic inks directly onto unglazed tile surfaces prior to firing, allowing for photorealistic reproductions of complex patterns, textures, and images. This technology utilizes piezoelectric printheads to deposit inks with resolutions reaching up to 1200 dpi, far surpassing traditional methods and facilitating intricate designs that mimic natural materials like stone or wood.[79] The printing process involves sequential pigment layering on the tile substrate, followed by drying and high-temperature firing at approximately 1200°C in a roller kiln, which vitrifies the inks and bonds them permanently to the tile body without altering the underlying structure.[80] Complementing this, diamond etching employs computer numerical control (CNC) machines equipped with diamond-tipped tools to score precise grooves into the tile surface, creating 3D textures such as wood-grain effects with controlled depths typically ranging from 0.1 to 1 mm, thereby avoiding significant material removal while adding tactile depth.[81] These etching operations are particularly valued for producing anti-slip surfaces through fine grooves or decorative patterns that integrate seamlessly with printed designs.[82] Innovations in these techniques continue to expand applications, including the use of UV-curable inks for glass tiles, which polymerize instantly under ultraviolet light to enable durable, high-resolution prints on non-porous surfaces without requiring thermal firing.[83] Hybrid methods combining digital printing with etching have emerged for custom architectural panels, where inks provide color and detail followed by CNC scoring for relief effects, allowing bespoke creations tailored to specific project needs.[84] The adoption of these advanced techniques since the 2010s has significantly impacted the tile market by reducing production waste from traditional levels of around 20%—due to screen printing misalignments and overproduction—to less than 5%, primarily through on-demand printing that minimizes defects and excess inventory.[85] This efficiency supports mass customization, enabling manufacturers to produce short runs of unique designs economically and meeting diverse consumer demands for personalized flooring and wall coverings.Mathematics and Design Principles

Tiling Patterns and Geometry

Tiling patterns in geometry involve arranging plane figures, known as tiles, to cover a surface completely without gaps or overlaps. A fundamental requirement for many tilings is the edge-to-edge condition, where tiles meet vertex-to-vertex along their entire edges, ensuring a structured and non-overlapping arrangement. Tilings are classified as periodic if the pattern repeats translationally in two independent directions, forming a lattice-like structure, or aperiodic if no such translational periodicity exists despite covering the plane exhaustively.[86][87] Monohedral tilings use congruent copies of a single tile shape. Among regular polygons, only equilateral triangles, squares, and regular hexagons admit edge-to-edge monohedral tilings of the Euclidean plane, as their internal angles sum appropriately to 360 degrees at each vertex. These tilings form planar graphs where vertices (V), edges (E), and faces (F)—with tiles as faces—satisfy Euler's formula for connected planar graphs:This relation constrains possible configurations, for instance, implying that the average number of edges per face in a tiling is at most 6 for infinite planar networks.[88][89] Advanced tessellations extend these ideas through polyominoes, which are connected unions of squares, and specialized tiles like Wang tiles. Introduced by Hao Wang in 1961, Wang tiles are unit squares with colored edges that must match adjacently, enabling the construction of algorithmic patterns and proving undecidability in tiling problems. Penrose tilings, developed by Roger Penrose in the 1970s, employ two rhombi with angles of 36°/144° and 72°/108° to generate aperiodic, non-repeating quasiperiodic structures exhibiting fivefold rotational symmetry. A notable advancement came in 2023 with the discovery of the first aperiodic monotile, a single tile shape dubbed the "hat" that can tile the plane only in non-periodic ways, solving the long-standing "einstein" problem in tiling theory.[90][86][91] Historical mathematical explorations include Islamic girih tiles, a set of five shapes—such as decagons and bowties—used in medieval architecture to produce intricate patterns with decagonal symmetry, effectively creating quasiperiodic designs centuries before their formal discovery. M.C. Escher drew inspiration from such geometries for his "impossible" tilings, particularly in works like the Circle Limit series (1958–1960), which depict hyperbolic tilings where more than six motifs meet at a vertex, defying Euclidean constraints. Coverage theorems ensure that convex tiles can tile the Euclidean plane without gaps or overlaps when their shapes allow full angular complementarity at vertices, as verified for all triangles and quadrilaterals.[92][93][87]