Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Asymptomatic

View on Wikipedia

Asymptomatic (or clinically silent) is an adjective categorising the medical conditions (i.e., injuries or diseases) that patients carry but without experiencing their symptoms, despite an explicit diagnosis (e.g., a positive medical test).

Pre-symptomatic is the adjective categorising the time periods during which the medical conditions are asymptomatic.

Subclinical and paucisymptomatic are other adjectives categorising either the asymptomatic infections (i.e., subclinical infections), or the psychosomatic illnesses and mental disorders expressing a subset of symptoms but not the entire set an explicit medical diagnosis requires.

Examples

[edit]An example of an asymptomatic disease is cytomegalovirus (CMV) which is a member of the herpes virus family. "It is estimated that 1% of all newborns are infected with CMV, but the majority of infections are asymptomatic." (Knox, 1983; Kumar et al. 1984)[1] In some diseases, the proportion of asymptomatic cases can be important. For example, in multiple sclerosis it is estimated that around 25% of the cases are asymptomatic, with these cases detected postmortem or just by coincidence (as incidental findings) while treating other diseases.[2]

Importance

[edit]Knowing that a condition is asymptomatic is important because:

- It may be contagious, and the contribution of asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic infections to the transmission level of a disease helps set the required control measures to keep it from spreading.[3]

- It is not required that a person undergo treatment. It does not cause later medical problems such as high blood pressure and hyperlipidaemia.[4]

- Be alert to possible problems: asymptomatic hypothyroidism makes a person vulnerable to Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome or beri-beri following intravenous glucose.[5]

- For some conditions, treatment during the asymptomatic phase is vital. If one waits until symptoms develop, it is too late for survival or to prevent damage.

Mental health

[edit]Subclinical or subthreshold conditions are those for which the full diagnostic criteria are not met and have not been met in the past, although symptoms are present. This can mean that symptoms are not severe enough to merit a diagnosis,[6] or that symptoms are severe but do not meet the criteria of a condition.[7]

List

[edit]These are conditions for which there is a sufficient number of documented individuals that are asymptomatic that it is clinically noted. For a complete list of asymptomatic infections see subclinical infection.

- Balanitis xerotica obliterans

- Benign lymphoepithelial lesion

- Cardiac shunt

- Carotid artery dissection

- Carotid bruit

- Cavernous hemangioma

- Chloromas (Myeloid sarcoma)

- Cholera

- Chronic myelogenous leukemia

- Coeliac disease

- Coronavirus (common cold germs)

- Coronary artery disease

- COVID-19

- Cowpox

- Diabetic retinopathy

- Essential fructosuria

- Flu or Influenza strains

- Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma

- Glioblastoma multiforme (occasionally)

- Glucocorticoid remediable aldosteronism

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

- Hepatitis

- Hereditary elliptocytosis

- Herpes

- Heterophoria

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Histidinemia

- HIV (AIDS)

- HPV

- Hyperaldosteronism

- hyperlipidaemia

- Hyperprolinemia type I

- Hypothyroidism

- Hypoxia (some cases)

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

- Iridodialysis (when small)

- Lesch–Nyhan syndrome (female carriers)

- Levo-Transposition of the great arteries

- Measles

- Meckel's diverticulum

- Microvenular hemangioma

- Mitral valve prolapse

- Monkeypox

- Monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis

- Myelolipoma

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Optic disc pit

- Osteoporosis

- Pertussis (whooping cough)

- Pes cavus

- Poliomyelitis

- Polyorchidism

- Pre-eclampsia

- Prehypertension

- Protrusio acetabuli

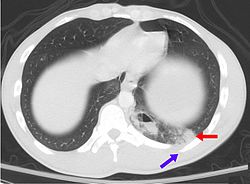

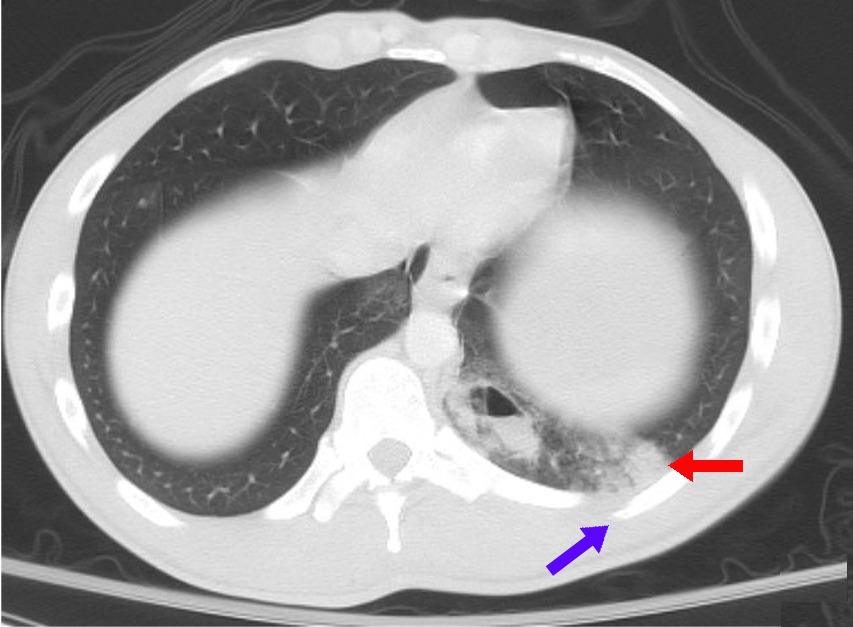

- Pulmonary contusion

- Renal tubular acidosis

- Rubella

- Smallpox (extinct since the 1980s)

- Spermatocele

- Sphenoid wing meningioma

- Spider angioma

- Splenic infarction (though not typically)

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Tonsillolith

- Tuberculosis

- Type II diabetes

- Typhus

- Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia

- Varicella (chickenpox)

- Wilson's disease

Millions of women reported lack of symptoms during pregnancy until the point of childbirth or the beginning of labor and did not know they were pregnant. This phenomenon is known as cryptic pregnancies.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Vinson, B. (2012). Language Disorders Across the Lifespan. p. 94. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar

- ^ Engell T (May 1989). "A clinical patho-anatomical study of clinically silent multiple sclerosis". Acta Neurol Scand. 79 (5): 428–30. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.1989.tb03811.x. PMID 2741673. S2CID 21581253.

- ^ Buitrago-Garcia, Diana; Egli-Gany, Dianne; Counotte, Michel J.; Hossmann, Stefanie; Imeri, Hira; Ipekci, Aziz Mert; Salanti, Georgia; Low, Nicola (2020-09-22). "Occurrence and transmission potential of asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections: A living systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 17 (9) e1003346. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003346. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 7508369. PMID 32960881.

- ^ Tattersall, R (2001). "Diseases the doctor (or autoanalyser) says you have got". Clinical Medicine. 1 (3). London: 230–3. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.1-3-230. PMC 4951914. PMID 11446622.

- ^ Watson, A. J.; Walker, J. F.; Tomkin, G. H.; Finn, M. M.; Keogh, J. A. (1981). "Acute Wernickes encephalopathy precipitated by glucose loading". Irish Journal of Medical Science. 150 (10): 301–303. doi:10.1007/BF02938260. PMID 7319764. S2CID 23063090.

- ^ Ji, Jianlin (October 2012). "Distinguishing subclinical (subthreshold) depression from the residual symptoms of major depression". Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry. 24 (5): 288–289. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2012.05.007. ISSN 1002-0829. PMC 4198879. PMID 25328354.

- ^ Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1. OCLC 830807378.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "What is a Cryptic Pregnancy?". 10 September 2019.

Asymptomatic

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Terminology

Core Definition

In medicine, asymptomatic describes a state in which an individual harbors a pathogen, disease, or medical condition without manifesting any clinical signs or symptoms.[6][7] This includes both subjective experiences, such as fever, pain, or fatigue, and objective indicators detectable through physical examination or basic testing.[8] Asymptomatic cases are confirmed via laboratory methods, like pathogen detection in samples, despite the absence of illness indicators.[9] The term encompasses asymptomatic carriers—persons infected with a transmissible agent who remain clinically silent and may unknowingly propagate the pathogen through shedding or contact.[5][2] Unlike presymptomatic states, where symptoms emerge later in the infection course, true asymptomatic infection persists without symptom onset throughout.[10] This distinction relies on longitudinal observation, as initial asymptomatic presentations can evolve if symptoms develop subsequently.[11] Asymptomatic conditions occur across infectious and non-infectious diseases, complicating detection without targeted screening.[12]Distinctions from Related Concepts

Asymptomatic infection or carriage denotes the presence of a pathogen or disease state in an individual who exhibits no clinical symptoms whatsoever, even upon thorough clinical evaluation, throughout the entire duration of the condition.[13] This strict absence of manifestations distinguishes it from presymptomatic infection, which refers to the early phase of an illness—typically during the incubation period—where the host is infected, often infectious, but has not yet developed symptoms that are expected to emerge subsequently.[14] For instance, in SARS-CoV-2 dynamics, presymptomatic individuals may transmit the virus 1–2 days before symptom onset, whereas truly asymptomatic cases involve no such progression to symptomatic disease.[15] Subclinical infection, by contrast, encompasses cases where the pathogen elicits minimal or no overt signs, potentially below the threshold for clinical detection, but may involve detectable subclinical physiological responses such as localized inflammation or immune activation without patient-perceived symptoms.[16] Although the terms asymptomatic and subclinical are frequently conflated in epidemiological reporting—particularly for infections like tuberculosis or HIV where laboratory evidence confirms presence without illness—the former emphasizes a complete lack of symptomatology, while the latter allows for inapparent but biologically active processes that could theoretically progress if unmonitored.[17] In veterinary and human pathology, subclinical states often represent a transitional or latent phase preceding potential clinical disease, unlike persistent asymptomatic carriage.[18] Paucisymptomatic (or oligosymptomatic) conditions differ by featuring a sparse array of mild symptoms insufficient to warrant typical diagnosis or intervention, such as isolated low-grade fever or subtle discomfort, which may evade self-reporting or routine screening.[13] This contrasts with asymptomatic purity, as paucisymptomatic cases inherently involve some symptomatic expression, albeit attenuated, and are sometimes reclassified under broader "mild" categories in studies of pathogens like influenza or Ebola, where follow-up reveals overlooked signs in up to 20–30% of initially deemed asymptomatic cohorts.[19] Precise delineation requires prospective monitoring, as retrospective self-reports can blur boundaries, leading to overestimation of truly asymptomatic prevalence in cross-sectional data.[20]Examples in Medical Conditions

Infectious Diseases

In infectious diseases, asymptomatic infection denotes the harboring of a pathogen by a host in the absence of clinical symptoms, frequently enabling silent transmission through pathogen shedding in bodily fluids or secretions.[1] This state contrasts with symptomatic cases by lacking overt signs like fever or organ dysfunction, yet infectivity persists, complicating outbreak control as carriers evade detection via symptom surveillance.[21] Bacterial examples abound, notably in typhoid fever (Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi), where 2–5% of acute cases evolve into chronic asymptomatic carriage, with bacteria persisting in the gallbladder and shedding via feces, perpetuating fecal-oral transmission.[22] A historical case is Mary Mallon, identified in 1907 as the first documented asymptomatic carrier in the United States; as a cook, she infected at least 51 individuals across multiple households, causing three fatalities, despite never exhibiting symptoms herself.[23] Viral pathogens similarly exhibit high rates of asymptomatic infection. Poliovirus infections are asymptomatic in approximately 70% of pediatric cases, with virus excretion in nasopharyngeal secretions and stool enabling person-to-person spread before paralysis develops in rare symptomatic subsets (about 0.5%).[24] Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) features a chronic asymptomatic phase, or clinical latency, following acute infection; this stage, lasting a median of 10 years without antiretroviral therapy, sustains viral replication at lower levels while permitting transmission via blood, semen, or other fluids.[25] Hepatitis B virus (HBV) chronicity often manifests as inactive carriage, affecting over 300 million people globally, where individuals remain seropositive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) without liver enzyme elevations or symptoms, yet transmit via perinatal, sexual, or percutaneous routes.[26] Influenza viruses demonstrate that asymptomatic infections can match symptomatic ones in viral load and shedding duration, contributing 20–50% of transmission chains in modeled epidemics, as evidenced by serological and virological studies.[27] The asymptomatic rate (percentage of infections with no symptoms) for Influenza A varies widely depending on study methods, definitions, and populations. Meta-analyses report pooled estimates around 16-21% for strictly asymptomatic cases, with ranges from about 4% to over 80%. For example, one meta-analysis of outbreak investigations using virologic confirmation found 16% (95% CI 13-19%), while adjusted longitudinal studies suggest higher rates of 65-85%. Another meta-analysis reported 21% (95% CI 4-41%) specifically for influenza A, highlighting high heterogeneity across studies.[27][28] Parasitic diseases like malaria harbor asymptomatic Plasmodium reservoirs in endemic areas, sustaining low-level transmission via mosquito vectors despite no fever or anemia.[29] Overall, these cases highlight asymptomatic hosts as key epidemiological drivers, necessitating targeted screening—such as stool cultures for typhoid carriers or serological tests for HBV—to mitigate spread, particularly in high-risk settings like food handling or healthcare.[1]Non-Infectious Conditions

Numerous non-infectious conditions progress asymptomatically for extended periods, posing risks due to delayed detection and intervention. These include cardiovascular disorders like hypertension and atherosclerosis, metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, and various malignancies, where absence of symptoms often leads to underdiagnosis until complications arise.[8][12] Routine screening is critical for identifying these cases, as empirical data show high prevalence among adults without overt signs.[30] Hypertension frequently remains asymptomatic, earning the moniker "silent killer" due to its lack of symptoms despite elevating risks for stroke and heart disease. In the United States, hypertension affects over 30% of adults, with many cases undiagnosed until routine checks or end-organ damage occurs.[31] Among nursing home residents, prevalence reaches up to 75%, often presenting without symptoms.[32] Globally, only 54% of adults aged 30-79 with hypertension are diagnosed, underscoring widespread asymptomatic persistence.[33] Type 2 diabetes commonly manifests asymptomatically, with estimates indicating up to 50% of patients experience no noticeable symptoms at diagnosis despite elevated blood glucose levels.[34] In the US, approximately 28% of the 31 million adults with diabetes—around 8.7 million individuals—are undiagnosed, equivalent to 3.4% of the total adult population.[35] Undiagnosed cases elevate cardiovascular risks, with screening recommended for asymptomatic overweight adults aged 35-70.[36] Atherosclerosis, the buildup of plaques in arteries, typically advances asymptomatically for decades before clinical events like myocardial infarction.[37] In a cohort of asymptomatic US adults, 49% exhibited coronary plaque via imaging, highlighting subclinical prevalence independent of symptoms.[38] Progression in such cases correlates with increased all-cause mortality risk, as evidenced by longitudinal studies tracking plaque burden without initial symptoms.[39] Cancers often develop asymptomatically in early stages, termed "silent cancers," complicating timely detection without screening. Prostate, thyroid, and certain breast cancers may remain symptom-free for years, detectable only via imaging or biomarkers.[40] Multicancer early detection tests aim to identify over 50 types in asymptomatic adults aged 50+, though their clinical utility depends on validation trials showing reduced mortality.[30] Asymptomatic progression underscores the value of population-based screening, as delays permit metastatic spread.[41] Other examples include glaucoma, where elevated intraocular pressure damages vision silently until advanced loss occurs, and high cholesterol, which contributes to atherosclerosis without direct symptoms.[12] These conditions emphasize causal links between undetected pathology and downstream morbidity, favoring evidence-based screening over reactive diagnosis.[42]Detection and Diagnosis

Screening Methods

Screening for asymptomatic conditions involves applying diagnostic tests to apparently healthy individuals to detect subclinical disease or infection, often guided by risk factors, prevalence, and test performance characteristics.[43] These methods prioritize high sensitivity to minimize false negatives, though specificity varies to reduce overdiagnosis.[44] In infectious diseases, nucleic acid amplification tests like reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on respiratory or other specimens represent the gold standard for identifying asymptomatic viral carriers, as demonstrated in SARS-CoV-2 surveillance where they confirm active replication without symptoms.[45] Rapid antigen detection tests offer a less invasive, point-of-care alternative for scalable population screening, detecting viral proteins in asymptomatic cases with reasonable sensitivity in high-prevalence settings.[46] For bacterial pathogens, culture-based methods, such as urine cultures for asymptomatic bacteriuria, provide definitive identification but require longer turnaround times.[47] Serological testing for antibodies supports retrospective detection of asymptomatic exposure, particularly in outbreak investigations.30254-6/fulltext) Non-infectious asymptomatic conditions rely on physiological and biochemical assays during routine evaluations. Blood pressure measurement via sphygmomanometry screens for hypertension, a silent precursor to cardiovascular events, recommended annually for adults over age 18. Fasting plasma glucose, oral glucose tolerance tests, or hemoglobin A1c assays identify preclinical type 2 diabetes, with A1c thresholds of ≥5.7% flagging prediabetes in asymptomatic screening programs.[48] Cancer screening employs imaging and biomarkers, including mammography for detecting non-palpable breast tumors and fecal immunochemical tests or colonoscopy for colorectal polyps in average-risk populations starting at age 45.[49] Epidemiological strategies integrate these tools through universal or targeted approaches, such as pre-admission PCR in hospitals or contact-tracing swabs, to isolate asymptomatic transmitters efficiently.[50] Test selection balances analytical validity, clinical utility, and logistical feasibility, with molecular methods favored for acute threats despite higher costs.[51]Diagnostic Challenges

Diagnosing asymptomatic conditions presents fundamental challenges due to the absence of clinical symptoms that typically prompt medical evaluation, leading to underdetection unless targeted screening is implemented.[50] In infectious diseases, such as malaria or SARS-CoV-2, asymptomatic carriers often harbor low pathogen loads that evade standard diagnostic thresholds, resulting in false negatives from tests like microscopy or rapid antigen assays.[52][53] This issue is exacerbated in low-prevalence settings, where the positive predictive value of screening tests diminishes, increasing the risk of unnecessary interventions from false positives.[54] Screening programs for asymptomatic disease, while essential for early identification, are constrained by logistical and technical limitations, including reagent shortages, high costs, and the need for repeated testing to capture transient infections.[55] For instance, in bacterial infections like chlamydia, single-specimen nucleic acid amplification tests exhibit sensitivities below 90%, underscoring the inadequacy of one-time screening for reliable detection.[54] Non-infectious conditions, such as carotid artery stenosis, further illustrate these hurdles; ultrasound screening in asymptomatic adults yields low yield due to the rarity of progression to stroke, with potential harms from angiography outweighing benefits, as evidenced by U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations against routine use.[56][57] Distinguishing truly asymptomatic cases from pre-symptomatic ones adds complexity, as serial testing is often required to confirm status, straining public health resources and complicating isolation strategies.[15] Empirical data from COVID-19 surveillance indicate that symptom-agnostic approaches, like mass PCR testing, detect up to 40-45% of infections missed by symptom-based triage, yet scalability remains limited by throughput and error rates in real-world deployment.[58] Overall, these diagnostic barriers necessitate balancing test sensitivity against specificity, with ongoing advancements in point-of-care technologies aimed at addressing low-level pathogen detection, though widespread adoption lags due to validation needs.[53]Epidemiological Role

Transmission Dynamics

Asymptomatic individuals facilitate pathogen transmission by remaining socially active without self-isolation or symptom-based quarantine, thereby sustaining chains of infection undetected by surveillance systems. In infectious diseases, these carriers often exhibit prolonged shedding periods, contributing variably to overall transmission depending on pathogen characteristics and host factors. Empirical reviews of 15 key pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, and parasites, reveal that asymptomatic infectious periods occur in nearly all cases, with relative infectiousness ranging from 0% to 100% compared to symptomatic counterparts.[1] The contribution of asymptomatic cases to total transmission spans 0% to 96%, driven by differences in viral load, shedding duration, and contact patterns. For instance, in poliomyelitis, 97% of infections are asymptomatic and account for 99% of transmission due to high fecal-oral shedding without behavioral disruption. In contrast, for SARS-CoV-2, asymptomatic cases represent about 50% of infections with a relative infectiousness of 75% that of symptomatic cases, contributing roughly 55% to spread through respiratory droplets during a typical 5-day asymptomatic window. Bacterial examples include typhoid fever, where 80% of Salmonella Typhi infections are asymptomatic, and 3-4% progress to chronic carriage lasting up to 10 years, enabling fecal-oral transmission via contaminated food or water as exemplified by historical carriers like Mary Mallon, who infected dozens without symptoms.[1][59] Meta-analyses consistently show reduced infectivity in asymptomatic versus symptomatic cases, attributed to lower pathogen titers; for SARS-CoV-2, the pooled secondary attack rate from asymptomatic index cases is 1.79% (95% CI: 0.41%-3.16%), significantly below presymptomatic (5.02%) and symptomatic rates, with a 42% lower relative risk overall. This dynamic elevates the effective reproduction number (Re) in populations with high asymptomatic fractions, as undetected spread amplifies outbreaks before interventions target symptoms. However, in diseases like HIV, asymptomatic infectiousness is markedly lower at 24%, limiting their role relative to acute phases. Such variability underscores the need for pathogen-specific modeling, where asymptomatic transmission can undermine herd immunity thresholds by extending outbreak tails.[60][61][1]Public Health Strategies

Public health strategies for addressing asymptomatic infections emphasize proactive surveillance and containment to counteract undetected transmission, as traditional symptom-based detection often fails to capture carriers who contribute to ongoing spread. Core measures include targeted screening and diagnostic testing in high-risk settings, such as healthcare facilities or communities with elevated incidence, to identify infections lacking clinical signs; for instance, nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are recommended for asymptomatic individuals in long-term care facilities regardless of known exposure.[62] [63] Upon detection, isolation protocols typically mandate separation for 10–14 days, calibrated to the pathogen's incubation and shedding periods, thereby preventing onward contagion from confirmed asymptomatic carriers.[50] [64] Contact tracing extends these efforts by systematically identifying and monitoring exposures linked to asymptomatics, often combined with quarantine for close contacts to interrupt chains of transmission that evade symptom surveillance.[65] In pathogens with substantial asymptomatic infectivity, such as certain respiratory viruses, population-scale interventions like universal masking or group size limits supplement individual-level controls, particularly when modeling indicates that high asymptomatic proportions necessitate broad suppression to reduce overall incidence.[66] [67] Empirical evaluations underscore that overlooking asymptomatics in control programs squanders opportunities for interruption, as seen in historical management of diseases like typhoid fever where carrier identification via stool cultures enabled targeted exclusion from food handling roles.[68] Challenges in implementation arise from resource constraints and variable infectivity; for example, while mass testing enhances detection in outbreaks, its efficacy diminishes if asymptomatic shedding is low or tests yield false negatives, prompting prioritization of PCR-based methods over antigen tests for precision.[15] Behavioral strategies, including voluntary stay-home advisories post-exposure, further bolster prevention by curbing mild or subclinical cases, though adherence relies on public trust and clear communication of risks grounded in pathogen-specific data.[69] Overall, these approaches succeed when integrated with epidemiological modeling that quantifies asymptomatic contributions, avoiding overreliance on symptomatic isolation alone, which studies show underperforms against silent drivers of epidemics.[70][66]Controversies and Evidence Debates

Asymptomatic Transmission in COVID-19

Asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 refers to the spread of the virus by individuals who test positive but never develop symptoms throughout their infection, distinct from presymptomatic transmission, which occurs before symptoms emerge in those who later become symptomatic.[15] Early pandemic modeling and public health guidance, such as from the CDC, estimated that asymptomatic cases could account for 35-40% of infections and a substantial fraction of overall transmission, influencing policies like universal masking and testing.[71] However, these estimates often conflated asymptomatic with presymptomatic cases, and subsequent empirical studies using contact tracing and viral load data revealed lower infectivity from truly asymptomatic carriers.[72] Meta-analyses of contact-tracing data indicate that the secondary attack rate (SAR) from asymptomatic index cases is approximately 1.79% (95% CI: 0.41%-3.16%), significantly lower than the 5.02% for presymptomatic (95% CI: 2.37%-7.66%) and 5.27% for symptomatic cases (95% CI: 2.40%-8.15%).[60] In household settings, the SAR rises to 4.22% (95% CI: 0.91%-7.52%) for asymptomatic transmitters, but remains below symptomatic levels, with no secondary infections observed from asymptomatic cases in some outbreaks involving 22 non-household and 20 household contacts.[60][72] The relative transmission risk from asymptomatic infections is about 0.32 times that of symptomatic ones (95% CI: 0.16-0.64), reflecting lower viral shedding and absence of symptom-driven behaviors like coughing.[73] Systematic reviews estimate the pooled proportion of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections that remain asymptomatic at 35.1% (95% CI: 30.7%-39.9%), rising to 47.3% (95% CI: 34.0%-61.0%) in studies with complete follow-up screening to distinguish persistent asymptomacy from delayed symptom onset.[74] Children show higher rates (46.7%, 95% CI: 32.0%-62.0%) than the elderly (19.7%, 95% CI: 12.7%-29.4%), with significant heterogeneity across studies due to varying follow-up durations and screening rigor.[74] Despite comparable viral loads in some asymptomatic cases, presymptomatic phases account for over 50% of transmissions in modeling, underscoring that asymptomatic spread, while possible, contributes minimally to epidemic dynamics compared to symptomatic and presymptomatic routes.[74][73] These findings, drawn from outbreak investigations and cohort studies, suggest that targeting symptomatic individuals and presymptomatic windows through rapid testing yields greater control than broad asymptomatic screening alone, as asymptomatic carriers pose limited population-level risk.[72] Limitations include potential under-detection of mild transmissions and biases in early data from high-prevalence settings like long-term care, but consistent evidence across regions affirms reduced asymptomatic infectivity.[74][60]Empirical Data on Infectivity

Empirical studies on the infectivity of asymptomatic carriers, particularly for SARS-CoV-2, reveal that truly asymptomatic individuals (those who never develop symptoms) generally exhibit lower transmission potential compared to symptomatic or presymptomatic cases, though transmission is possible, especially in household settings.[60][72] A 2022 meta-analysis of transmission risks estimated the pooled secondary attack rate from asymptomatic infections at 1.79% (95% CI: 0.53%–3.04%), significantly lower than presymptomatic (5.02%) and symptomatic infections (3.17%–18.43% across variants).[60] This lower rate aligns with findings from contact tracing in Taiwan during 2020, where no secondary transmissions occurred from 55 truly asymptomatic index cases, contrasted with a 7.4% secondary attack rate from presymptomatic exposures.[72] Viral load data provide mechanistic insights into reduced infectivity. While some early studies reported comparable cycle threshold (Ct) values—indicative of similar viral loads—between asymptomatic and symptomatic cases, meta-analyses and variant-specific research indicate generally lower peak loads and shorter shedding durations in truly asymptomatic individuals.[75][76] For instance, a 2020 study of asymptomatic U.S. Marine recruits found median Ct values of 27.5 (IQR: 22.3–31.5), overlapping with symptomatic ranges but with prolonged positivity in some cases without correlating to higher transmission.[75] In children, asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections consistently show lower upper respiratory viral loads than symptomatic ones, potentially limiting aerosol generation.[77] Household transmission studies highlight variability but underscore modest overall contribution from asymptomatic carriers. A 2024 analysis of pediatric cases reported that contacts of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2-positive children were approximately five times more likely to develop symptomatic illness within two weeks compared to contacts of uninfected children, suggesting viable transmission risk in close settings.[78] However, broader reviews estimate asymptomatic infections account for 10%–20% of total transmissions, far less than presymptomatic (up to 40%–50%) or symptomatic cases, with infectivity influenced by factors like variant (e.g., lower for Omicron) and host immunity.[79][80]| Study Type | Asymptomatic Transmission Rate/SAR | Comparison to Symptomatic/Presymptomatic | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis (global, multi-study) | 1.79% (pooled SAR) | Lower than presymptomatic (5.02%), symptomatic (3.17%–18.43%) | [60] |

| Contact tracing (Taiwan, 2020) | 0% (no secondary cases from 55 indices) | Presymptomatic: 7.4%; Symptomatic: variable but higher | [72] |

| Household pediatric (2024) | ~5x risk of symptomatic illness in contacts | Elevated vs. uninfected controls, but absolute rates low | [78] |