Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ebola

View on Wikipedia

| Ebola | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Ebola haemorrhagic fever (EHF), Ebola virus disease |

| |

| Two nurses standing near Mayinga N'Seka, a nurse with Ebola virus disease in the 1976 outbreak in Zaire. N'Seka died a few days later. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, sore throat, muscular pain, headaches, diarrhoea, bleeding[1] |

| Complications | Shock from fluid loss[2] |

| Usual onset | Two days to three weeks post exposure[1] |

| Causes | Ebolaviruses spread by direct contact[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Finding the virus, viral RNA, or antibodies in blood[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Malaria, cholera, typhoid fever, meningitis, other viral haemorrhagic fevers[1] |

| Prevention | Coordinated medical services, careful handling of bushmeat[1] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[1] |

| Medication | Atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab (Inmazeb) |

| Prognosis | 25–90% mortality[1] |

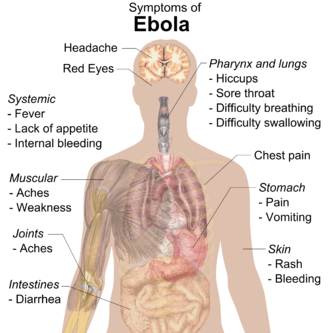

Ebola, also known as Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF), is a viral hemorrhagic fever in humans and other primates, caused by ebolaviruses.[1] Symptoms typically start anywhere between two days and three weeks after infection.[3] The first symptoms are usually fever, sore throat, muscle pain, and headaches.[1] These are usually followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash and decreased liver and kidney function,[1] at which point some people begin to bleed both internally and externally.[1] It kills between 25% and 90% of those infected – about 50% on average.[1] Death is often due to shock from fluid loss, and typically occurs between 6 and 16 days after the first symptoms appear.[2] Early treatment of symptoms increases the survival rate considerably compared to late start.[4] An Ebola vaccine was approved by the US FDA in December 2019.

The virus spreads through direct contact with body fluids, such as blood from infected humans or other animals,[1] or from contact with items that have recently been contaminated with infected body fluids.[1] There have been no documented cases, either in nature or under laboratory conditions, of spread through the air between humans or other primates.[5] After recovering from Ebola, semen or breast milk may continue to carry the virus for anywhere between several weeks to several months.[1][6][7] Fruit bats are believed to be the normal carrier in nature; they are able to spread the virus without being affected by it.[1] The symptoms of Ebola may resemble those of several other diseases, including malaria, cholera, typhoid fever, meningitis and other viral hemorrhagic fevers.[1] Diagnosis is confirmed by testing blood samples for the presence of viral RNA, viral antibodies or the virus itself.[1][8]

Control of outbreaks requires coordinated medical services and community engagement,[1] including rapid detection, contact tracing of those exposed, quick access to laboratory services, care for those infected, and proper disposal of the dead through cremation or burial.[1][9] Prevention measures involve wearing proper protective clothing and washing hands when in close proximity to patients and while handling potentially infected bushmeat, as well as thoroughly cooking bushmeat.[1] While there is no approved treatment for Ebola as of 2019[update],[10] two treatments (atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab and ansuvimab) are associated with improved outcomes.[11] Supportive efforts also improve outcomes.[1] These include oral rehydration therapy (drinking slightly sweetened and salty water) or giving intravenous fluids, and treating symptoms.[1] In October 2020, atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab (Inmazeb) was approved for medical use in the United States to treat the disease caused by Zaire ebolavirus.[12]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Onset

[edit]The length of time between exposure to the virus and the development of symptoms (incubation period) is between 2 and 21 days,[1][13] and usually between 4 and 10 days.[14] However, recent estimates based on mathematical models predict that around 5% of cases may take longer than 21 days to develop.[15]

Symptoms usually begin with a sudden influenza-like stage characterised by fatigue, fever, weakness, decreased appetite, muscular pain, joint pain, headache, and sore throat.[1][14][16][17] The fever is usually higher than 38.3 °C (101 °F).[18] This is often followed by nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and sometimes hiccups.[17][19] The combination of severe vomiting and diarrhoea often leads to severe dehydration.[20] Next, shortness of breath and chest pain may occur, along with swelling, headaches, and confusion.[17] In about half of the cases, the skin may develop a maculopapular rash, a flat red area covered with small bumps, five to seven days after symptoms begin.[14][18]

Bleeding

[edit]In some cases, internal and external bleeding may occur.[1] This typically begins five to seven days after the first symptoms.[21] All infected people show some decreased blood clotting.[18] Bleeding from mucous membranes or from sites of needle punctures has been reported in 40–50% of cases.[22] This may cause vomiting blood, coughing up of blood, or blood in stool.[23] Bleeding into the skin may create petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses or haematomas (especially around needle injection sites).[24] Bleeding into the whites of the eyes may also occur.[25] Heavy bleeding is uncommon; if it occurs, it is usually in the gastrointestinal tract.[26] The incidence of bleeding into the gastrointestinal tract was reported to be ~58% in the 2001 outbreak in Gabon,[27] but in the 2014–15 outbreak in the US it was ~18%,[28] possibly due to improved prevention of disseminated intravascular coagulation.[20]

Recovery or death

[edit]Recovery may begin between seven and 14 days after first symptoms.[17] Death, if it occurs, follows typically six to sixteen days from first symptoms and is often due to shock from fluid loss.[2] In general, bleeding often indicates a worse outcome, and blood loss may result in death.[16] People are often in a coma near the end of life.[17]

Those who survive often have ongoing muscular and joint pain, liver inflammation, and decreased hearing, and may have continued tiredness, continued weakness, decreased appetite, and difficulty returning to pre-illness weight.[17][29] Problems with vision may develop.[30] It is recommended that survivors of EVD wear condoms for at least twelve months after initial infection or until the semen of a male survivor tests negative for Ebola virus on two separate occasions.[31]

Survivors develop antibodies against Ebola that last at least 10 years, but it is unclear whether they are immune to additional infections.[32]

Cause

[edit]EVD in humans is caused by four of six viruses of the genus Ebolavirus. The four are Bundibugyo virus (BDBV), Sudan virus (SUDV), Taï Forest virus (TAFV) and one simply called Ebola virus (EBOV, formerly Zaire Ebola virus).[33] EBOV, species Zaire ebolavirus, is the most dangerous of the known EVD-causing viruses, and is responsible for the largest number of outbreaks.[34] The fifth and sixth viruses, Reston virus (RESTV) and Bombali virus (BOMV),[35] are not thought to cause disease in humans, but have caused disease in other primates.[36][37] All six viruses are closely related to marburgviruses.[33]

Virology

[edit]

Ebolaviruses contain single-stranded, non-infectious RNA genomes.[38] Ebolavirus genomes contain seven genes including 3'-UTR-NP-VP35-VP40-GP-VP30-VP24-L-5'-UTR.[24][39] The genomes of the five different ebolaviruses (BDBV, EBOV, RESTV, SUDV and TAFV) differ in sequence and the number and location of gene overlaps. As with all filoviruses, ebolavirus virions are filamentous particles that may appear in the shape of a shepherd's crook, of a "U" or of a "6," and they may be coiled, toroid or branched.[39][40] In general, ebolavirions are 80 nanometers (nm) in width and may be as long as 14,000 nm.[41]

Their life cycle is thought to begin with a virion attaching to specific cell-surface receptors such as C-type lectins, DC-SIGN, or integrins, which is followed by fusion of the viral envelope with cellular membranes.[42] The virions taken up by the cell then travel to acidic endosomes and lysosomes where the viral envelope glycoprotein GP is cleaved.[42] This processing appears to allow the virus to bind to cellular proteins enabling it to fuse with internal cellular membranes and release the viral nucleocapsid.[42] The Ebolavirus structural glycoprotein (known as GP1,2) is responsible for the virus' ability to bind to and infect targeted cells.[43] The viral RNA polymerase, encoded by the L gene, partially uncoats the nucleocapsid and transcribes the genes into positive-strand mRNAs, which are then translated into structural and nonstructural proteins. The most abundant protein produced is the nucleoprotein, whose concentration in the host cell determines when L switches from gene transcription to genome replication. Replication of the viral genome results in full-length, positive-strand antigenomes that are, in turn, transcribed into genome copies of negative-strand virus progeny.[44] Newly synthesised structural proteins and genomes self-assemble and accumulate near the inside of the cell membrane. Virions bud off from the cell, gaining their envelopes from the cellular membrane from which they bud. The mature progeny particles then infect other cells to repeat the cycle. The genetics of the Ebola virus are difficult to study because of EBOV's virulent characteristics.[45]

Transmission

[edit]

It is believed that between people, Ebola disease spreads only by direct contact with the blood or other body fluids of a person who has developed symptoms of the disease.[46][47][48] Body fluids that may contain Ebola viruses include saliva, mucus, vomit, feces, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine and semen.[6][32] The WHO states that only people who are very sick are able to spread Ebola disease in saliva, and the virus has not been reported to be transmitted through sweat. Most people spread the virus through blood, feces and vomit.[49] Entry points for the virus include the nose, mouth, eyes, open wounds, cuts and abrasions.[32] Ebola may be spread through large droplets; however, this is believed to occur only when a person is very sick.[50] This contamination can happen if a person is splashed with droplets.[50] Contact with surfaces or objects contaminated by the virus, particularly needles and syringes, may also transmit the infection.[51][52] The virus is able to survive on objects for a few hours in a dried state, and can survive for a few days within body fluids outside of a person.[32][53]

The Ebola virus may be able to persist for more than three months in the semen after recovery, which could lead to infections via sexual intercourse.[6][54][55] Virus persistence in semen for over a year has been recorded in a national screening programme.[56] Ebola may also occur in the breast milk of women after recovery, and it is not known when it is safe to breastfeed again.[7] The virus was also found in the eye of one patient, in 2014, two months after it was cleared from his blood.[57] Otherwise, people who have recovered are not infectious.[51]

The potential for widespread infections in countries with medical systems capable of observing correct medical isolation procedures is considered low.[58] Usually when someone has symptoms of the disease, they are unable to travel without assistance.[59]

Dead bodies remain infectious; thus, people handling human remains in practices such as traditional burial rituals or more modern processes such as embalming are at risk.[58] Of the cases of Ebola infections in Guinea during the 2014 outbreak, 69% are believed to have been contracted via unprotected (or unsuitably protected) contact with infected corpses during certain Guinean burial rituals.[60][61]

Health-care workers treating people with Ebola are at greatest risk of infection.[51] The risk increases when they do not have appropriate protective clothing such as masks, gowns, gloves and eye protection; do not wear it properly; or handle contaminated clothing incorrectly.[51] This risk is particularly common in parts of Africa where the disease mostly occurs and health systems function poorly.[62] There has been transmission in hospitals in some African countries that reuse hypodermic needles.[63][64] Some health-care centres caring for people with the disease do not have running water.[65] In the United States the spread to two medical workers treating infected patients prompted criticism of inadequate training and procedures.[66]

Human-to-human transmission of EBOV through the air has not been reported to occur during EVD outbreaks,[5] and airborne transmission has only been demonstrated in very strict laboratory conditions, and then only from pigs to primates, but not from primates to primates.[46][52] Spread of EBOV by water, or food other than bushmeat, has not been observed.[51][52] No spread by mosquitos or other insects has been reported.[51] Other possible methods of transmission are being studied.[53]

Airborne transmission among humans is theoretically possible due to the presence of Ebola virus particles in saliva, which can be discharged into the air with a cough or sneeze, but observational data from previous epidemics suggests the actual risk of airborne transmission is low.[67] A number of studies examining airborne transmission broadly concluded that transmission from pigs to primates could happen without direct contact because, unlike humans and primates, pigs with EVD get very high ebolavirus concentrations in their lungs, and not their bloodstream.[68] Therefore, pigs with EVD can spread the disease through droplets in the air or on the ground when they sneeze or cough.[69] By contrast, humans and other primates accumulate the virus throughout their body and specifically in their blood, but not very much in their lungs.[69] It is believed that this is the reason researchers have observed pig to primate transmission without physical contact, but no evidence has been found of primates being infected without actual contact, even in experiments where infected and uninfected primates shared the same air.[68][69]

Initial case

[edit]

Although it is not entirely clear how Ebola initially spreads from animals to humans, the spread is believed to involve direct contact with an infected wild animal or fruit bat.[51] Besides bats, other wild animals that are sometimes infected with EBOV include several species of monkeys such as baboons, great apes (chimpanzees and gorillas), and duikers (a species of antelope).[73]

Animals may become infected when they eat fruit partially eaten by bats carrying the virus.[74] Fruit production, animal behavior and other factors may trigger outbreaks among animal populations.[74]

Evidence indicates that both domestic dogs and pigs can also be infected with EBOV.[75] Dogs do not appear to develop symptoms when they carry the virus, and pigs appear to be able to transmit the virus to at least some primates.[75] Although some dogs in an area in which a human outbreak occurred had antibodies to EBOV, it is unclear whether they played a role in spreading the disease to people.[75]

Reservoir

[edit]The natural reservoir for Ebola has yet to be confirmed; however, bats are considered to be the most likely candidate.[52] Three types of fruit bats (Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti and Myonycteris torquata) were found to possibly carry the virus without getting sick.[76] As of 2013[update], whether other animals are involved in its spread is not known.[75] Plants, arthropods, rodents, and birds have also been considered possible viral reservoirs.[1][20]

Bats were known to roost in the cotton factory in which the first cases of the 1976 and 1979 outbreaks were observed, and they have also been implicated in Marburg virus infections in 1975 and 1980.[77] Of 24 plant and 19 vertebrate species experimentally inoculated with EBOV, only bats became infected.[78] The bats displayed no clinical signs of disease, which is considered evidence that these bats are a reservoir species of EBOV. In a 2002–2003 survey of 1,030 animals including 679 bats from Gabon and the Republic of the Congo, immunoglobulin G (IgG) immune defense molecules indicative of Ebola infection were found in three bat species; at various periods of study, between 2.2 and 22.6% of bats were found to contain both RNA sequences and IgG molecules indicating Ebola infection.[79] Antibodies against Zaire and Reston viruses have been found in fruit bats in Bangladesh, suggesting that these bats are also potential hosts of the virus and that the filoviruses are present in Asia.[80]

Between 1976 and 1998, in 30,000 mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and arthropods sampled from regions of EBOV outbreaks, no Ebola virus was detected apart from some genetic traces found in six rodents (belonging to the species Mus setulosus and Praomys) and one shrew (Sylvisorex ollula) collected from the Central African Republic.[77][81] However, further research efforts have not confirmed rodents as a reservoir.[82] Traces of EBOV were detected in the carcasses of gorillas and chimpanzees during outbreaks in 2001 and 2003, which later became the source of human infections. However, the high rates of death in these species resulting from EBOV infection make it unlikely that these species represent a natural reservoir for the virus.[77]

Deforestation has been mentioned as a possible contributor to recent outbreaks, including the West African Ebola virus epidemic. Index cases of EVD have often been close to recently deforested lands.[83][84]

Pathophysiology

[edit]

Like other filoviruses, EBOV replicates very efficiently in many cells, producing large amounts of virus in monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells and other cells including liver cells, fibroblasts, and adrenal gland cells.[85] Viral replication triggers high levels of inflammatory chemical signals and leads to a septic state.[29]

EBOV is thought to infect humans through contact with mucous membranes or skin breaks.[46] After infection, endothelial cells (cells lining the inside of blood vessels), liver cells, and several types of immune cells such as macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells are the main targets of attack.[46] Following infection, immune cells carry the virus to nearby lymph nodes where further reproduction of the virus takes place.[46] From there the virus can enter the bloodstream and lymphatic system and spread throughout the body.[46] Macrophages are the first cells infected with the virus, and this infection results in programmed cell death.[41] Other types of white blood cells, such as lymphocytes, also undergo programmed cell death leading to an abnormally low concentration of lymphocytes in the blood.[46] This contributes to the weakened immune response seen in those infected with EBOV.[46]

Endothelial cells may be infected within three days after exposure to the virus.[41] The breakdown of endothelial cells leading to blood vessel injury can be attributed to EBOV glycoproteins. This damage occurs due to the synthesis of Ebola virus glycoprotein (GP), which reduces the availability of specific integrins responsible for cell adhesion to the intercellular structure and causes liver damage, leading to improper clotting. The widespread bleeding that occurs in affected people causes swelling and shock due to loss of blood volume.[86] The dysfunctional bleeding and clotting commonly seen in EVD has been attributed to increased activation of the extrinsic pathway of the coagulation cascade due to excessive tissue factor production by macrophages and monocytes.[14]

After infection, a secreted glycoprotein, small soluble glycoprotein (sGP or GP) is synthesised. EBOV replication overwhelms protein synthesis of infected cells and the host immune defences. The GP forms a trimeric complex, which tethers the virus to the endothelial cells. The sGP forms a dimeric protein that interferes with the signalling of neutrophils, another type of white blood cell. This enables the virus to evade the immune system by inhibiting early steps of neutrophil activation.[medical citation needed] Furthermore, the virus is capable of hijacking cellular metabolism. Studies have shown that Ebola virus-like particles can reprogram metabolism in both vascular and immune cells.[87]

Immune system evasion

[edit]Filoviral infection also interferes with proper functioning of the innate immune system.[42][44] EBOV proteins blunt the human immune system's response to viral infections by interfering with the cells' ability to produce and respond to interferon proteins such as interferon-alpha, interferon-beta, and interferon gamma.[43][88]

The VP24 and VP35 structural proteins of EBOV play a key role in this interference. When a cell is infected with EBOV, receptors located in the cell's cytosol (such as RIG-I and MDA5) or outside of the cytosol (such as Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9) recognise infectious molecules associated with the virus.[43] On TLR activation, proteins including interferon regulatory factor 3 and interferon regulatory factor 7 trigger a signalling cascade that leads to the expression of type 1 interferons.[43] The type 1 interferons are then released and bind to the IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 receptors expressed on the surface of a neighbouring cell.[43] Once interferon has bound to its receptors on the neighbouring cell, the signalling proteins STAT1 and STAT2 are activated and move to the cell's nucleus.[43] This triggers the expression of interferon-stimulated genes, which code for proteins with antiviral properties.[43] EBOV's V24 protein blocks the production of these antiviral proteins by preventing the STAT1 signalling protein in the neighbouring cell from entering the nucleus.[43] The VP35 protein directly inhibits the production of interferon-beta.[88] By inhibiting these immune responses, EBOV may quickly spread throughout the body.[41]

Diagnosis

[edit]When EVD is suspected, travel, work history, and exposure to wildlife are important factors with respect to further diagnostic efforts.[89]

Laboratory testing

[edit]Possible non-specific laboratory indicators of EVD include a low platelet count; an initially decreased white blood cell count followed by an increased white blood cell count; elevated levels of the liver enzymes alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST); and abnormalities in blood clotting often consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) such as a prolonged prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and bleeding time.[90] Filovirions such as EBOV may be identified by their unique filamentous shapes in cell cultures examined with electron microscopy.[91]

The specific diagnosis of EVD is confirmed by isolating the virus, detecting its RNA or proteins, or detecting antibodies against the virus in a person's blood.[92] Isolating the virus by cell culture, detecting the viral RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)[8][14] and detecting proteins by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) are methods best used in the early stages of the disease and also for detecting the virus in human remains.[8][92] Detecting antibodies against the virus is most reliable in the later stages of the disease and in those who recover.[92] IgM antibodies are detectable two days after symptom onset and IgG antibodies can be detected six to 18 days after symptom onset.[14] During an outbreak, isolation of the virus with cell culture methods is often not feasible. In field or mobile hospitals, the most common and sensitive diagnostic methods are real-time PCR and ELISA.[93] In 2014, with new mobile testing facilities deployed in parts of Liberia, test results were obtained 3–5 hours after sample submission.[94] In 2015, a rapid antigen test which gives results in 15 minutes was approved for use by WHO.[95] It is able to confirm Ebola in 92% of those affected and rule it out in 85% of those not affected.[95]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Early symptoms of EVD may be similar to those of other diseases common in Africa, including malaria and dengue fever.[16] The symptoms are also similar to those of other viral haemorrhagic fevers such as Marburg virus disease, Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever, and Lassa fever.[96][97]

The complete differential diagnosis is extensive and requires consideration of many other infectious diseases such as typhoid fever, shigellosis, rickettsial diseases, cholera, sepsis, borreliosis, EHEC enteritis, leptospirosis, scrub typhus, plague, Q fever, candidiasis, histoplasmosis, trypanosomiasis, visceral leishmaniasis, measles, and viral hepatitis among others.[98]

Non-infectious diseases that may result in symptoms similar to those of EVD include acute promyelocytic leukaemia, haemolytic uraemic syndrome, snake envenomation, clotting factor deficiencies/platelet disorders, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia, Kawasaki disease, and warfarin poisoning.[93][99][100][101]

Prevention

[edit]Vaccines

[edit]An Ebola vaccine, rVSV-ZEBOV, was approved in the United States in December 2019.[102] It appears to be fully effective ten days after being given.[102] It was studied in Guinea between 2014 and 2016.[102] More than 100,000 people have been vaccinated against Ebola as of 2019[update].[103] The WHO reported that approximately 345,000 people were given the vaccine during the Kivu Ebola epidemic from 2018 to 2020.[104]

Infection control

[edit]

Community awareness of the benefits on survival chances of admitting cases early is important for the infected and infection control [4]

Caregivers

[edit]

People who care for those infected with Ebola should wear protective clothing including masks, gloves, gowns and goggles.[105] The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommend that the protective gear leaves no skin exposed.[106] These measures are also recommended for those who may handle objects contaminated by an infected person's body fluids.[107] In 2014, the CDC began recommending that medical personnel receive training on the proper suit-up and removal of personal protective equipment (PPE); in addition, a designated person, appropriately trained in biosafety, should be watching each step of these procedures to ensure they are done correctly.[106] In Sierra Leone, the typical training period for the use of such safety equipment lasts approximately 12 days.[108] In 2022 in Uganda, lighter personal protection equipment has become available as well as possibilities to monitor and communicate with patients from windows in the treatment tents until it is necessary to enter if e.g. a patient's oxygen levels drop.[4]

Patients and household members

[edit]The infected person should be in barrier-isolation from other people.[105] All equipment, medical waste, patient waste and surfaces that may have come into contact with body fluids need to be disinfected.[107] During the 2014 outbreak, kits were put together to help families treat Ebola disease in their homes, which included protective clothing as well as chlorine powder and other cleaning supplies.[109] Education of caregivers in these techniques, and providing such barrier-separation supplies has been a priority of Doctors Without Borders.[110]

Disinfection

[edit]Ebolaviruses can be eliminated with heat (heating for 30 to 60 minutes at 60 °C or boiling for five minutes). To disinfect surfaces, some lipid solvents such as some alcohol-based products, detergents, sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or calcium hypochlorite (bleaching powder), and other suitable disinfectants may be used at appropriate concentrations.[73][111]

General population

[edit]Education of the general public about the risk factors for Ebola infection and of the protective measures individuals may take to prevent infection is recommended by the World Health Organization.[1] These measures include avoiding direct contact with infected people and regular hand washing using soap and water.[112]

Bushmeat

[edit]Bushmeat, an important source of protein in the diet of some Africans, should be handled and prepared with appropriate protective clothing and thoroughly cooked before consumption.[1] Some research suggests that an outbreak of Ebola disease in the wild animals used for consumption may result in a corresponding human outbreak. Since 2003, such animal outbreaks have been monitored to predict and prevent Ebola outbreaks in humans.[113]

Corpses, burial

[edit]If a person with Ebola disease dies, direct contact with the body should be avoided.[105] Certain burial rituals, which may have included making various direct contacts with a dead body, require reformulation so that they consistently maintain a proper protective barrier between the dead body and the living.[114][115][116] Social anthropologists may help find alternatives to traditional rules for burials.[117]

Transport, travel, contact

[edit]Transportation crews are instructed to follow a certain isolation procedure, should anyone exhibit symptoms resembling EVD.[118] As of August 2014[update], the WHO does not consider travel bans to be useful in decreasing spread of the disease.[59] In October 2014, the CDC defined four risk levels used to determine the level of 21-day monitoring for symptoms and restrictions on public activities.[119] In the United States, the CDC recommends that restrictions on public activity, including travel restrictions, are not required for the following defined risk levels:[119]

- having been in a country with widespread Ebola disease transmission and having no known exposure (low risk); or having been in that country more than 21 days ago (no risk)

- encounter with a person showing symptoms; but not within three feet of the person with Ebola without wearing PPE; and no direct contact with body fluids

- having had brief skin contact with a person showing symptoms of Ebola disease when the person was believed to be not very contagious (low risk)

- in countries without widespread Ebola disease transmission: direct contact with a person showing symptoms of the disease while wearing PPE (low risk)

- contact with a person with Ebola disease before the person was showing symptoms (no risk).

The CDC recommends monitoring for the symptoms of Ebola disease for those both at "low risk" and at higher risk.[119]

Laboratory

[edit]In laboratories where diagnostic testing is carried out, biosafety level 4-equivalent containment is required.[120] Laboratory researchers must be properly trained in BSL-4 practices and wear proper PPE.[120]

Isolation

[edit]Isolation refers to separating those who are sick from those who are not. Quarantine refers to separating those who may have been exposed to a disease until they either show signs of the disease or are no longer at risk.[121] Quarantine, also known as enforced isolation, is usually effective in decreasing spread.[122][123] Governments often quarantine areas where the disease is occurring or individuals who may transmit the disease outside of an initial area.[124] In the United States, the law allows quarantine of those infected with ebolaviruses.[125][126]

Contact tracing

[edit]Contact tracing is considered important to contain an outbreak. It involves finding everyone who had close contact with infected individuals and monitoring them for signs of illness for 21 days. If any of these contacts comes down with the disease, they should be isolated, tested and treated. Then the process is repeated, tracing the contacts' contacts.[127][128]

Management

[edit]As of 2019[update] two treatments (atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab and ansuvimab) are associated with improved outcomes.[10][11] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advises people to be careful of advertisements making unverified or fraudulent claims of benefits supposedly gained from various anti-Ebola products.[129][130]

In October 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab with an indication for the treatment of infection caused by Zaire ebolavirus.[12]

Standard support

[edit]

Treatment is primarily supportive in nature.[131] Early supportive care with rehydration and symptomatic treatment improves survival.[1] Rehydration may be via the oral or intravenous route.[131] These measures may include pain management, and treatment for nausea, fever, and anxiety.[131] The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends avoiding aspirin or ibuprofen for pain management, due to the risk of bleeding associated with these medications.[132]

Blood products such as packed red blood cells, platelets, or fresh frozen plasma may also be used.[131] Other regulators of coagulation have also been tried including heparin in an effort to prevent disseminated intravascular coagulation and clotting factors to decrease bleeding.[131] Antimalarial medications and antibiotics are often used before the diagnosis is confirmed,[131] though there is no evidence to suggest such treatment helps. Several experimental treatments are being studied.[133]

Where hospital care is not possible, the WHO's guidelines for home care have been relatively successful. Recommendations include using towels soaked in a bleach solution when moving infected people or bodies and also applying bleach on stains. It is also recommended that the caregivers wash hands with bleach solutions and cover their mouth and nose with a cloth.[134]

Intensive care

[edit]Intensive care is often used in the developed world.[24] This may include maintaining blood volume and electrolytes (salts) balance as well as treating any bacterial infections that may develop.[24] Dialysis may be needed for kidney failure, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may be used for lung dysfunction.[24]

Prognosis

[edit]EVD has a risk of death in those infected of between 25% and 90%.[1][135] As of September 2014[update], the average risk of death among those infected is 50%.[1] The highest risk of death was 90% in the 2002–2003 Republic of the Congo outbreak.[136] Early admission significantly increases survival rates [4]

Death, if it occurs, follows typically six to sixteen days after symptoms appear and is often due to low blood pressure from fluid loss.[2] Early supportive care to prevent dehydration may reduce the risk of death.[133]

Post-Ebola virus syndrome

[edit]If an infected person survives, recovery may be quick and complete.[14][137] However, a large portion of survivors develop post-Ebola virus syndrome after the acute phase of the infection.[138]

Prolonged cases are often complicated by the occurrence of long-term problems, such as inflammation of the testicles, joint pains, fatigue, hearing loss, mood and sleep disturbances, muscular pain, abdominal pain, menstrual abnormalities, miscarriages, skin peeling, or hair loss.[14][137] Inflammation and swelling of the uveal layer of the eye is the most common eye complication in survivors of Ebola virus disease.[137] Eye symptoms, such as light sensitivity, excess tearing, and vision loss have been described.[139]

Ebola can stay in some body parts like the eyes,[140] breasts, and testicles after infection.[6][141] Sexual transmission after recovery has been suspected.[142][143] If sexual transmission occurs following recovery, it is believed to be a rare event.[144] One case of a condition similar to meningitis has been reported many months after recovery, as of October 2015[update].[145]

Epidemiology

[edit]The disease typically occurs in outbreaks in tropical regions of Sub-Saharan Africa.[1] From 1976 (when it was first identified) through 2013, the WHO reported 2,387 confirmed cases with 1,590 overall fatalities.[1][146] The largest outbreak to date was the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa, which caused a large number of deaths in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia.[147][148]

1976

[edit]Sudan

[edit]

The first known outbreak of EVD was identified only after the fact. It occurred between June and November 1976, in Nzara, South Sudan[33][149] (then part of Sudan), and was caused by Sudan virus (SUDV). The Sudan outbreak infected 284 people and killed 151. The first identifiable case in Sudan occurred on 27 June in a storekeeper in a cotton factory in Nzara, who was hospitalised on 30 June and died on 6 July.[24][150] Although the WHO medical staff involved in the Sudan outbreak knew that they were dealing with a heretofore unknown disease, the actual "positive identification" process and the naming of the virus did not occur until some months later in Zaire.[150]

Zaire

[edit]

On 26 August 1976, the second outbreak of EVD began in Yambuku, a small rural village in Mongala District in northern Zaire (now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo).[151][152] This outbreak was caused by EBOV, formerly designated Zaire ebolavirus, a different member of the genus Ebolavirus than in the first Sudan outbreak. The first person infected with the disease was the village school's headmaster Mabalo Lokela, who began displaying symptoms on 26 August 1976.[153] Lokela had returned from a trip to Northern Zaire near the border of the Central African Republic, after visiting the Ebola River between 12 and 22 August. He was originally believed to have malaria and was given quinine. However, his symptoms continued to worsen, and he was admitted to Yambuku Mission Hospital on 5 September. Lokela died on 8 September 14 days after he began displaying symptoms.[154][155]

Soon after Lokela's death, others who had been in contact with him also died, and people in Yambuku began to panic. The country's Minister of Health and Zaire President Mobutu Sese Seko declared the entire region, including Yambuku and the country's capital, Kinshasa, a quarantine zone. No-one was permitted to enter or leave the area, and roads, waterways, and airfields were placed under martial law. Schools, businesses and social organisations were closed.[156] The initial response was led by Congolese doctors, including Jean-Jacques Muyembe-Tamfum, one of the discoverers of Ebola. Muyembe took a blood sample from a Belgian nun; this sample would eventually be used by Peter Piot to identify the previously unknown Ebola virus.[157] Muyembe was also the first scientist to come into direct contact with the disease and survive.[158] Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), including Piot, co-discoverer of Ebola, later arrived to assess the effects of the outbreak, observing that "the whole region was in panic."[159][160][161]

Piot concluded that Belgian nuns had inadvertently started the epidemic by giving unnecessary vitamin injections to pregnant women without sterilizing the syringes and needles. The outbreak lasted 26 days and the quarantine lasted two weeks. Researchers speculated that the disease disappeared due to the precautions taken by locals, the quarantine of the area, and discontinuing of the injections.[156]

During this outbreak, Ngoy Mushola recorded the first clinical description of EVD in Yambuku, where he wrote the following in his daily log: "The illness is characterised with a high temperature of about 39 °C (102 °F), haematemesis, diarrhoea with blood, retrosternal abdominal pain, prostration with 'heavy' articulations, and rapid evolution death after a mean of three days."[162]

The virus responsible for the initial outbreak, first thought to be the Marburg virus, was later identified as a new type of virus related to the genus Marburgvirus. Virus strain samples isolated from both outbreaks were named "Ebola virus" after the Ebola River, near the first-identified viral outbreak site in Zaire.[24] Reports conflict about who initially coined the name: either Karl Johnson of the American CDC team[163] or Belgian researchers.[164] Subsequently, a number of other cases were reported, almost all centred on the Yambuku mission hospital or close contacts of another case.[153] In all, 318 cases and 280 deaths (an 88% fatality rate) occurred in Zaire.[165] Although the two outbreaks were at first believed connected, scientists later realised that they were caused by two distinct ebolaviruses, SUDV and EBOV.[152]

1995–2014

[edit]

The second major outbreak occurred in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, DRC), in 1995, affecting 315 and killing 254.[1]

In 2000, Uganda had an outbreak infecting 425 and killing 224; in this case, the Sudan virus was found to be the Ebola species responsible for the outbreak.[1]

In 2003, an outbreak in the DRC infected 143 and killed 128, a 90% death rate, the highest of a genus Ebolavirus outbreak to date.[166]

In 2004, a Russian scientist died from Ebola after sticking herself with an infected needle.[167]

Between April and August 2007, a fever epidemic[168] in a four-village region[169] of the DRC was confirmed in September to have been cases of Ebola.[170] Many people who attended the recent funeral of a local village chief died.[169] The 2007 outbreak eventually infected 264 individuals and killed 187.[1]

On 30 November 2007, the Uganda Ministry of Health confirmed an outbreak of Ebola in the Bundibugyo District in Western Uganda. After confirming samples tested by the United States National Reference Laboratories and the Centers for Disease Control, the World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed the presence of a new species of genus Ebolavirus, which was tentatively named Bundibugyo.[171] The WHO reported 149 cases of this new strain and 37 of those led to deaths.[1]

The WHO confirmed two small outbreaks in Uganda in 2012, both caused by the Sudan variant. The first outbreak affected seven people, killing four, and the second affected 24, killing 17.[1]

On 17 August 2012, the Ministry of Health of the DRC reported an outbreak of the Ebola-Bundibugyo variant[172] in the eastern region.[173][174] Other than its discovery in 2007, this was the only time that this variant has been identified as responsible for an outbreak. The WHO revealed that the virus had sickened 57 people and killed 29. The probable cause of the outbreak was tainted bush meat hunted by local villagers around the towns of Isiro and Viadana.[1][175]

In 2014, an outbreak occurred in the DRC. Genome-sequencing showed that this outbreak was not related to the 2014–15 West Africa Ebola virus outbreak, but was the same EBOV species, the Zaire species.[176] It began in August 2014, and was declared over in November with 66 cases and 49 deaths.[177] This was the 7th outbreak in the DRC, three of which occurred during the period when the country was known as Zaire.[178]

2013–2016 West Africa

[edit]

In March 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a major Ebola outbreak in Guinea, a West African nation.[179] Researchers traced the outbreak to a one-year-old child who died in December 2013.[180][181] The disease rapidly spread to the neighbouring countries of Liberia and Sierra Leone. It was the largest Ebola outbreak ever documented, and the first recorded in the region.[179] On 8 August 2014, the WHO declared the epidemic an international public health emergency. Urging the world to offer aid to the affected regions, its Director-General said, "Countries affected to date simply do not have the capacity to manage an outbreak of this size and complexity on their own. I urge the international community to provide this support on the most urgent basis possible."[182] By mid-August 2014, Doctors Without Borders reported the situation in Liberia's capital, Monrovia, was "catastrophic" and "deteriorating daily". They reported that fears of Ebola among staff members and patients had shut down much of the city's health system, leaving many people without medical treatment for other conditions.[183] In a 26 September statement, WHO said, "The Ebola epidemic ravaging parts of West Africa is the most severe acute public health emergency seen in modern times. Never before in recorded history has a biosafety level four pathogen infected so many people so quickly, over such a broad geographical area, for so long."[184]

Intense contact tracing and strict isolation largely prevented further spread of the disease in the countries that had imported cases.

It caused significant mortality, with a considerable case fatality rate.[185][186][187][note 1] By the end of the epidemic, 28,616 people had been infected; of these, 11,310 had died, for a case-fatality rate of 40%.[188] As of 8 May 2016[update], 28,646 suspected cases and 11,323 deaths were reported;[189][190] however, the WHO said that these numbers may be underestimated.[191] Because they work closely with the body fluids of infected patients, healthcare workers were especially vulnerable to infection; in August 2014, the WHO reported that 10% of the dead were healthcare workers.[192]

In September 2014, it was estimated that the countries' capacity for treating Ebola patients was insufficient by the equivalent of 2,122 beds; by December there were a sufficient number of beds to treat and isolate all reported Ebola cases, although the uneven distribution of cases was causing serious shortfalls in some areas.[193] On 28 January 2015, the WHO reported that for the first time since the week ending 29 June 2014, there had been fewer than 100 new confirmed cases reported in a week in the three most-affected countries. The response to the epidemic then moved to a second phase, as the focus shifted from slowing transmission to ending the epidemic.[194] On 8 April 2015, the WHO reported only 30 confirmed cases, the lowest weekly total since the third week of May 2014.[195]

On 29 December 2015, 42 days after the last person tested negative for a second time, Guinea was declared free of Ebola transmission.[196] At that time, a 90-day period of heightened surveillance was announced by that agency. "This is the first time that all three countries – Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone – have stopped the original chains of transmission ...", the organisation stated in a news release.[197] A new case was detected in Sierra Leone on 14 January 2016.[198] However, the outbreak was declared no longer an emergency on 29 March 2016.[199]

2014 spread outside West Africa

[edit]On 19 September, Eric Duncan flew from his native Liberia to Texas; five days later he began showing symptoms and visited a hospital but was sent home. His condition worsened and he returned to the hospital on 28 September, where he died on 8 October. Health officials confirmed a diagnosis of Ebola on 30 September – the first case in the United States.[200]

In early October, Teresa Romero, a 44-year-old Spanish nurse, contracted Ebola after caring for a priest who had been repatriated from West Africa. This was the first transmission of the virus to occur outside Africa.[201] Romero tested negative for the disease on 20 October, suggesting that she may have recovered from Ebola infection.[202]

On 12 October, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed that a nurse in Texas, Nina Pham, who had treated Duncan tested positive for the Ebola virus, the first known case of transmission in the United States.[203] On 15 October, a second Texas health-care worker who had treated Duncan was confirmed to have the virus.[66][204] Both of these people recovered.[205] An unrelated case involved a doctor in New York City, who returned to the United States from Guinea after working with Médecins Sans Frontières and tested positive for Ebola on 23 October.[206] The person recovered and was discharged from Bellevue Hospital on 11 November.[205] On 24 December 2014, a laboratory in Atlanta, Georgia reported that a technician had been exposed to Ebola.[207]

On 29 December 2014, Pauline Cafferkey, a British nurse who had just returned to Glasgow from Sierra Leone, was diagnosed with Ebola at Glasgow's Gartnavel General Hospital.[208] After initial treatment in Glasgow, she was transferred by air to RAF Northolt, then to the specialist high-level isolation unit at the Royal Free Hospital in London for longer-term treatment.[209]

2017 Democratic Republic of the Congo

[edit]On 11 May 2017, the DRC Ministry of Public Health notified the WHO about an outbreak of Ebola. Four people died, and four people survived; five of these eight cases were laboratory-confirmed. A total of 583 contacts were monitored. On 2 July 2017, the WHO declared the end of the outbreak.[210]

2018 Équateur province

[edit]On 14 May 2018, the World Health Organization reported that "the Democratic Republic of Congo reported 39 suspected, probable or confirmed cases of Ebola between 4 April and 13 May, including 19 deaths."[211] Some 393 people identified as contacts of Ebola patients were being followed up. The outbreak centred on the Bikoro, Iboko, and Wangata areas in Equateur province,[211] including in the large city of Mbandaka. The DRC Ministry of Public Health approved the use of an experimental vaccine.[212][213][214] On 13 May 2018, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus visited Bikoro.[215] Reports emerged that maps of the area were inaccurate, not so much hampering medical providers as epidemiologists and officials trying to assess the outbreak and containment efforts.[216] The 2018 outbreak in the DRC was declared over on 24 July 2018.[217]

2018–2020 Kivu

[edit]On 1 August 2018, the world's 10th Ebola outbreak was declared in North Kivu province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It was the first Ebola outbreak in a military conflict zone, with thousands of refugees in the area.[218][219] By November 2018, nearly 200 Congolese had died of Ebola, about half of them from the city of Beni, where armed groups are fighting over the region's mineral wealth, impeding medical relief efforts.[220]

By March 2019, this became the second largest Ebola outbreak ever recorded, with more than 1,000 cases and insecurity continuing to be the major resistance to providing an adequate response.[221][222] As of 4 June 2019[update], the WHO reported 2025 confirmed and probable cases with 1357 deaths.[223] In June 2019, two people died of Ebola in neighbouring Uganda.[224]

In July 2019, an infected man travelled to Goma, home to more than two million people.[225] One week later, on 17 July 2019, the WHO declared the Ebola outbreak a global health emergency, the fifth time such a declaration has been made by the organisation.[226] A government spokesman said that half of the Ebola cases are unidentified, and he added that the current outbreak could last up to three years.[227]

On 25 June 2020, the second biggest EVD outbreak ever was declared over.[228]

2020 Équateur province

[edit]On 1 June 2020, the Congolese health ministry announced a new DRC outbreak of Ebola in Mbandaka, Équateur Province, a region along the Congo River. Genome sequencing suggests that this outbreak, the 11th outbreak since the virus was first discovered in the country in 1976, is unrelated to the one in North Kivu Province or the previous outbreak in the same area in 2018. It was reported that six cases had been identified; four of the people had died. It is expected that more people will be identified as surveillance activities increase.[229] By 15 June the case count had increased to 17 with 11 deaths, with more than 2,500 people having been vaccinated.[230] The 11th EVD outbreak was officially declared over on 19 November 2020.[231] By the time the Équateur outbreak ended, it had 130 confirmed cases with 75 recoveries and 55 deaths.

2021

[edit]North Kivu

[edit]On 7 February 2021, the Congolese health ministry announced a new case of Ebola near Butembo, North Kivu detected a day before. The case was a 42-year-old woman who had symptoms of Ebola in Biena on 1 February 2021. A few days after, she died in a hospital in Butembo. The WHO said that more than 70 people with contact with the woman had been tracked.[232][233]

On 11 February 2021, another woman who had contact with the previous woman died in the same town, and the number of traced contacts increased to 100.[234] A day after, a third case was detected in Butembo.[235]

On 3 May 2021, the 12th EVD outbreak was declared over, resulting in 12 cases and six deaths.[236][237] Heightened surveillance will continue for 90 days after the declaration, in case of resurgence.[236]

Guinea

[edit]In February 2021, Sakoba Keita, head of Guinea's national health agency confirmed that three people had died of Ebola in the south-eastern region near the city of Nzérékoré. A further five people also tested positive. Keita also confirmed more testing was underway, and attempts to trace and isolate further cases had begun.[238] On 14 February, the Guinean government declared an Ebola epidemic.[239] The outbreak may have started following reactivation of a latent case in a survivor of an earlier outbreak.[240][241] As of 4 May 2021, 23 cases were reported, with no new cases or deaths since 3 April 2021.[236] A 42-day countdown period was started on 8 May 2021, and on 19 June, the outbreak was declared over.[236][242]

Ivory Coast

[edit]On 14 August 2021, The Ministry of Health of Cote d’Ivoire confirmed the country's first case of Ebola since 1994. This came after the Institut Pasteur in Cote d'Ivoire confirmed the Ebola Virus Disease in samples collected from a patient, who was hospitalized in the commercial capital of Abidjan, after arriving from Guinea.[243]

However, on 31 August 2021, the WHO found that, after further tests in a laboratory in Lyon, the patient did not have Ebola. The cause of her disease is still being analyzed.[244]

2022

[edit]On 23 April 2022, a case of Ebola was confirmed in the DRC in the Equateur province. The case was a 31-year-old man whose symptoms began on 5 April, but did not seek treatment for over a week. On 21 April, he was admitted to an Ebola treatment centre and died later that day.[245] By 24 May 2022, there were 5 recorded deaths in the DRC.[246] On 15 August, the fifth case was buried, and the outbreak was declared over, 42 days after, on 4 July 2022.[247]

In September 2022, Uganda reported 7 cases infected with the Ebola Sudan strain,[248] but by mid-October the count had increased to 63.[249] In November 2022, the outbreak in Uganda continued — still without a vaccine.[4] On 10 January 2023, the outbreak was considered over after no new cases had been reported for 42 days; the outbreak killed nearly 80 people.[250]

History

[edit]Ebola was first identified in 1976, in two simultaneous outbreaks, one in Nzara (a town in South Sudan) and the other in Yambuku (the Democratic Republic of the Congo), a village near the Ebola River, for which the disease was named.[1] Ebola outbreaks occur intermittently in tropical regions of sub-Saharan Africa.[1] Between 1976 and 2012, according to the World Health Organization, there were 24 outbreaks of Ebola resulting in a total of 2,387 cases, and 1,590 deaths.[1][146] The largest Ebola outbreak to date was an epidemic in West Africa from December 2013 to January 2016, with 28,646 cases and 11,323 deaths.[189][147][148] On 29 March 2016, it was declared to no longer be an emergency.[199] Other outbreaks in Africa began in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in May 2017,[251][252] and 2018.[253][217] In July 2019, the World Health Organization declared the Congo Ebola outbreak a world health emergency.[254]

Society and culture

[edit]Weaponisation

[edit]Ebolavirus is classified as a biosafety level 4 agent, as well as a Category A bioterrorism agent by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[85][255] It has the potential to be weaponised for use in biological warfare,[256][257] and was investigated by Biopreparat for such use, but might be difficult to prepare as a weapon of mass destruction because the virus becomes ineffective quickly in open air.[258] Fake emails pretending to be Ebola information from the WHO or the Mexican government have, in 2014, been misused to spread computer malware.[259] The BBC reported in 2015 that "North Korean state media has suggested the disease was created by the U.S. military as a biological weapon."[260]

Literature

[edit]Richard Preston's 1995 best-selling book, The Hot Zone, dramatised the Ebola outbreak in Reston, Virginia.[261][262][263]

William Close's 1995 Ebola: A Documentary Novel of Its First Explosion[264][265] and 2002 Ebola: Through the Eyes of the People focused on individuals' reactions to the 1976 Ebola outbreak in Zaire.[266][267]

Tom Clancy's 1996 novel, Executive Orders, involves a Middle Eastern terrorist attack on the United States using an airborne form of a deadly Ebola virus strain named "Ebola Mayinga" (see Mayinga N'Seka).[268][269]

As the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa developed in 2014, a number of popular self-published and well-reviewed books containing sensational and misleading information about the disease appeared in electronic and printed formats. The authors of some such books admitted that they lacked medical credentials and were not technically qualified to give medical advice. The World Health Organization and the United Nations stated that such misinformation had contributed to the spread of the disease.[270]

Other animals

[edit]Wild animals

[edit]Ebola has a high mortality rate among primates.[271] Frequent outbreaks of Ebola may have resulted in the deaths of 5,000 gorillas.[272] Outbreaks of Ebola may have been responsible for an 88% decline in tracking indices of observed chimpanzee populations in the 420 km2 Lossi Sanctuary between 2002 and 2003.[273] Transmission among chimpanzees through meat consumption constitutes a significant risk factor, whereas contact between the animals, such as touching dead bodies and grooming, is not.[274]

Recovered gorilla carcasses have contained multiple Ebola virus strains, suggesting multiple introductions of the virus. Bodies decompose quickly and carcasses are not infectious after three to four days. Contact between gorilla groups is rare, suggesting that transmission among gorilla groups is unlikely, and that outbreaks result from transmission between viral reservoirs and animal populations.[273]

Domestic animals

[edit]In 2012, it was demonstrated that the virus can travel without contact from pigs to nonhuman primates, although the same study failed to achieve transmission in that manner between primates.[75][275]

Dogs may become infected with EBOV but not develop symptoms. Dogs in some parts of Africa scavenge for food, and they sometimes eat EBOV-infected animals and also the corpses of humans. A 2005 survey of dogs during an EBOV outbreak found that although they remain asymptomatic, about 32 percent of dogs closest to an outbreak showed a seroprevalence for EBOV versus nine percent of those farther away.[276] The authors concluded that there were "potential implications for preventing and controlling human outbreaks."

Reston virus

[edit]In late 1989, Hazelton Research Products' Reston Quarantine Unit in Reston, Virginia, had an outbreak of fatal illness amongst certain lab monkeys. This lab outbreak was initially diagnosed as simian haemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV) and occurred amongst a shipment of crab-eating macaque monkeys imported from the Philippines. Hazelton's veterinary pathologist in Reston sent tissue samples from dead animals to the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) at Fort Detrick, Maryland, where an ELISA test indicated the antibodies present in the tissue were a response to Ebola virus and not SHFV.[277] An electron microscopist from USAMRIID discovered filoviruses similar in appearance, in crystalloid aggregates and as single filaments with a shepherd's hook, to Ebola in the tissue samples sent from Hazelton Research Products' Reston Quarantine Unit.[278]

A US Army team headquartered at USAMRIID euthanised the surviving monkeys, and brought all the dead monkeys to Fort Detrick for study by the Army's veterinary pathologists and virologists, and eventual disposal under safe conditions.[277] Blood samples were taken from 178 animal handlers during the incident.[279] Of those, six animal handlers eventually seroconverted, including one who had cut himself with a bloody scalpel.[86][280] Despite its status as a Level‑4 organism and its apparent pathogenicity in monkeys, when the handlers did not become ill, the CDC concluded that the virus had a very low pathogenicity to humans.[280][281]

The Philippines and the United States had no previous cases of Ebola infection, and upon further isolation, researchers concluded it was another strain of Ebola, or a new filovirus of Asian origin, which they named Reston ebolavirus (RESTV) after the location of the incident.[277] Reston virus (RESTV) can be transmitted to pigs.[75] Since the initial outbreak it has since been found in nonhuman primates in Pennsylvania, Texas, and Italy,[282] where the virus had infected pigs.[283] According to the WHO, routine cleaning and disinfection of pig (or monkey) farms with sodium hypochlorite or detergents should be effective in inactivating the Reston ebolavirus. Pigs that have been infected with RESTV tend to show symptoms of the disease.[284]

Research

[edit]Treatments

[edit]

As of July 2015[update], no medication has been proven safe and effective for treating Ebola. By the time the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa began in 2013, there were at least nine different candidate treatments. Several trials were conducted in late 2014, and early 2015, but some were abandoned due to lack of efficacy or lack of people to study.[285]

As of August 2019[update], two experimental treatments known as atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab and ansuvimab were found to be 90% effective.[286][287][288]

Diagnostic tests

[edit]The diagnostic tests currently available require specialised equipment and highly trained personnel. Since there are few suitable testing centres in West Africa, this leads to delay in diagnosis.[289]

On 29 November 2014, a new 15-minute Ebola test was reported that if successful, "not only gives patients a better chance of survival, but it prevents transmission of the virus to other people." The new equipment, about the size of a laptop and solar-powered, allows testing to be done in remote areas.[290]

On 29 December 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the LightMix Ebola Zaire rRT-PCR test for patients with symptoms of Ebola.[291]

Disease models

[edit]Animal models and in particular non-human primates are being used to study different aspects of Ebola virus disease. Developments in organ-on-a-chip technology have led to a chip-based model for Ebola haemorrhagic syndrome.[292]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The mortality (number of dead per number of healthy per time frame) recorded in Liberia up to 26 August 2014 was 70%.[187] However, due to the estimation method used, the estimated case fatality rate (70.8%) for this particular epidemic differs from the actual ratio between the number of deaths and the number of cases.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar "Ebola virus disease, Fact sheet N°103, Updated September 2014". World Health Organization (WHO). September 2014. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d Singh SK, Ruzek D, eds. (2014). Viral hemorrhagic fevers. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 444. ISBN 978-1439884294. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016.

- ^ Modrow S, Falke D, Truyen U, Schätzl H (2013). "Viruses: Definition, Structure, Classification". In Modrow S, Falke D, Truyen U, Schätzl H (eds.). Molecular Virology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 17–30. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-20718-1_2. ISBN 978-3-642-20718-1. S2CID 83235976.

- ^ a b c d e Ebola in Uganda: Guiliani R. "Our game-changing treatment centres will save more lives". msf.org.urk. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ a b "2014 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak in West Africa". World Health Organization (WHO). 21 April 2014. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Preliminary study finds that Ebola virus fragments can persist in the semen of some survivors for at least nine months". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 14 October 2015. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017.

- ^ a b "Recommendations for Breastfeeding/Infant Feeding in the Context of Ebola". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 19 September 2014. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ a b c Broadhurst MJ, Brooks TJ, Pollock NR (13 July 2016). "Diagnosis of Ebola Virus Disease: Past, Present, and Future". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 29 (4). American Society for Microbiology: 773–793. doi:10.1128/cmr.00003-16. ISSN 0893-8512. LCCN 88647279. OCLC 38839512. PMC 5010747. PMID 27413095.

- ^ "Guidance for Safe Handling of Human Remains of Ebola Patients in U.S. Hospitals and Mortuaries". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Ebola Treatment Research". NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Independent Monitoring Board Recommends Early Termination of Ebola Therapeutics Trial in DRC Because of Favorable Results with Two of Four Candidates". NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 12 August 2019. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ a b "FDA Approves First Treatment for Ebola Virus". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 14 October 2020. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Signs and Symptoms". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 28 January 2014. Archived from the original on 1 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Goeijenbier M, van Kampen JJ, Reusken CB, Koopmans MP, van Gorp EC (November 2014). "Ebola virus disease: a review on epidemiology, symptoms, treatment and pathogenesis". Neth J Med. 72 (9): 442–448. PMID 25387613. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014.

- ^ Haas CN (14 October 2014). "On the Quarantine Period for Ebola Virus". PLOS Currents Outbreaks. 6. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.2ab4b76ba7263ff0f084766e43abbd89. ISSN 2157-3999. PMC 4205154. PMID 25642371.

- ^ a b c Gatherer D (August 2014). "The 2014 Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa". J Gen Virol. 95 (Pt 8): 1619–1624. doi:10.1099/vir.0.067199-0. PMID 24795448.

- ^ a b c d e f Magill A (2013). Hunter's tropical medicine and emerging infectious diseases (9th ed.). New York: Saunders. p. 332. ISBN 978-1416043904. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Hoenen T, Groseth A, Falzarano D, Feldmann H (May 2006). "Ebola virus: unravelling pathogenesis to combat a deadly disease". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 12 (5): 206–215. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.03.006. PMID 16616875.

- ^ Brown CS, Mepham S, Shorten RJ (June 2017). "Ebola Virus Disease: An Update on Epidemiology, Symptoms, Laboratory Findings, Diagnostic Issues, and Infection Prevention and Control Issues for Laboratory Professionals". Clinical Laboratory Medicine (Review). 37 (2): 269–284. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.01.003. PMID 28457350.

- ^ a b c Sharma N, Cappell MS (September 2015). "Gastrointestinal and Hepatic Manifestations of Ebola Virus Infection". Digestive Diseases and Sciences (Review). 60 (9): 2590–2603. doi:10.1007/s10620-015-3691-z. PMID 25972150. S2CID 5674317.

- ^ Simpson DI (1977). Marburg and Ebola virus infections: a guide for their diagnosis, management, and control. World Health Organization. p. 10f. hdl:10665/37138. ISBN 924170036X. WHO offset publication; no. 36.

- ^ King JW, Rafeek H (14 January 2021). Chandrasekar PH (ed.). "Ebola Virus, Clinical Presentation". Medscape. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Appendix A: Disease-Specific Chapters – Chapter: Hemorrhagic fevers caused by: i) Ebola virus and ii) Marburg virus and iii) Other viral causes including bunyaviruses, arenaviruses, and flaviviruses" (PDF). Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Feldmann H, Geisbert TW (March 2011). "Ebola haemorrhagic fever". Lancet. 377 (9768): 849–862. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60667-8. PMC 3406178. PMID 21084112.

- ^ Shantha JG, Yeh S, Nguyen QD (November 2016). "Ebola virus disease and the eye". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology (Review). 27 (6): 538–544. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000313. PMID 27585217. S2CID 34367099.

- ^ West TE, von Saint André-von Arnim A (November 2014). "Clinical presentation and management of severe Ebola virus disease". Annals of the American Thoracic Society (Review). 11 (9): 1341–1350. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201410-481PS. PMID 25369317.

- ^ Sharma N, Cappell MS (September 2015). "Gastrointestinal and Hepatic Manifestations of Ebola Virus Infection". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 60 (9): 2590–2603. doi:10.1007/s10620-015-3691-z. PMID 25972150. S2CID 5674317.

- ^ "Ebola virus disease Information for Clinicians in U.S. Healthcare Settings | For Clinicians | Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease) | Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 6 January 2020. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ a b Tosh PK, Sampathkumar P (December 2014). "What Clinicians Should Know About the 2014 Ebola Outbreak". Mayo Clin Proc. 89 (12): 1710–1717. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.10.010. PMID 25467644.

- ^ "An emergency within an emergency: caring for Ebola survivors". World Health Organization (WHO). 7 August 2015. Archived from the original on 13 August 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ "Ebola Virus Disease". SRHD. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Q&A on Transmission, Ebola". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). September 2014. Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ a b c Hoenen T, Groseth A, Feldmann H (July 2012). "Current Ebola vaccines". Expert Opin Biol Ther. 12 (7): 859–872. doi:10.1517/14712598.2012.685152. PMC 3422127. PMID 22559078.

- ^ Kuhn JH, Becker S, Ebihara H, Geisbert TW, Johnson KM, Kawaoka Y, et al. (December 2010). "Proposal for a revised taxonomy of the family Filoviridae: Classification, names of taxa and viruses, and virus abbreviations". Archives of Virology. 155 (12): 2083–2103. doi:10.1007/s00705-010-0814-x. PMC 3074192. PMID 21046175.

- ^ Branswell H (27 July 2018). "New Ebola species is reported for first time in a decade". Stat. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Spickler A. "Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus Infections" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2015.

- ^ "About Ebola Virus Disease". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ Pringle CR (2005). "Order Mononegavirales". In Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA (eds.). Virus Taxonomy – Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 609–614. ISBN 978-0-12-370200-5.

- ^ a b Stahelin RV (June 2014). "Membrane binding and bending in Ebola VP40 assembly and egress". Front Microbiol. 5: 300. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00300. PMC 4061899. PMID 24995005.

- ^ Ascenzi P, Bocedi A, Heptonstall J, Capobianchi MR, Di Caro A, Mastrangelo E, et al. (June 2008). "Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus: insight the Filoviridae family" (PDF). Mol Aspects Med. 29 (3): 151–185. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.005. hdl:2434/53604. PMID 18063023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d Chippaux JP (October 2014). "Outbreaks of Ebola virus disease in Africa: the beginnings of a tragic saga". J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 20 (1): 44. doi:10.1186/1678-9199-20-44. PMC 4197285. PMID 25320574.

- ^ a b c d Misasi J, Sullivan NJ (October 2014). "Camouflage and Misdirection: The Full-On Assault of Ebola Virus Disease". Cell. 159 (3): 477–486. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.006. PMC 4243531. PMID 25417101.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kühl A, Pöhlmann S (September 2012). "How Ebola virus counters the interferon system". Zoonoses Public Health. 59 (Supplement 2): 116–131. doi:10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01454.x. PMC 7165950. PMID 22958256.

- ^ a b Olejnik J, Ryabchikova E, Corley RB, Mühlberger E (August 2011). "Intracellular events and cell fate in filovirus infection". Viruses. 3 (8): 1501–1531. doi:10.3390/v3081501. PMC 3172725. PMID 21927676.

- ^ Feldmann H, Geisbert TW, Jahrling PB, Klenk H, Netesov SV, Peters CJ, Sanchez A, Swanepoel R, Volchkov VE (2005). Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA (eds.). Virus Taxonomy – Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier/Academic Press. ISBN 978-0123702005.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Funk DJ, Kumar A (November 2014). "Ebola virus disease: an update for anesthesiologists and intensivists". Can J Anaesth. 62 (1): 80–91. doi:10.1007/s12630-014-0257-z. PMC 4286619. PMID 25373801.

- ^ "Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease) Transmission". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 5 November 2014. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Drazen JM, Kanapathipillai R, Campion EW, Rubin EJ, Hammer SM, Morrissey S, Baden LR (November 2014). "Ebola and quarantine". N Engl J Med. 371 (21): 2029–2030. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1413139. PMID 25347231.

- ^ McNeil Jr DG (3 October 2014). "Ask Well: How Does Ebola Spread? How Long Can the Virus Survive?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ a b "How Ebola Is Spread" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1 November 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Transmission". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 17 October 2014. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d Chowell G, Nishiura H (October 2014). "Transmission dynamics and control of Ebola virus disease (EVD): a review". BMC Med. 12 (1): 196. doi:10.1186/s12916-014-0196-0. PMC 4207625. PMID 25300956.

- ^ a b Osterholm MT, Moore KA, Kelley NS, Brosseau LM, Wong G, Murphy FA, et al. (19 February 2015). "Transmission of Ebola viruses: what we know and what we do not know". mBio. 6 (2) e00137. doi:10.1128/mBio.00137-15. PMC 4358015. PMID 25698835.

- ^ "Sexual transmission of the Ebola Virus : evidence and knowledge gaps". World Health Organization (WHO). 4 April 2015. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ Wu B (2 May 2015). "Ebola Can Be Transmitted Through Sex". Science Times. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Soka MJ, Choi MJ, Baller A, White S, Rogers E, Purpura LJ, et al. (2016). "Prevention of sexual transmission of Ebola in Liberia through a national semen testing and counselling programme for survivors: an analysis of Ebola virus RNA results and behavioural data". Lancet Global Health. 4 (10): e736 – e743. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30175-9. PMID 27596037.

- ^ Varkey JB, Shantha JG, Crozier I, Kraft CS, Lyon GM, Mehta AK, et al. (7 May 2015). "Persistence of Ebola Virus in Ocular Fluid during Convalescence". The New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (25): 2423–2427. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500306. hdl:2328/35704. PMC 4547451. PMID 25950269.

- ^ a b "CDC Telebriefing on Ebola outbreak in West Africa". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 28 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2 August 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Air travel is low-risk for Ebola transmission". World Health Organization (WHO). 14 August 2014. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015.

- ^ Chan M (September 2014). "Ebola virus disease in West Africa – no early end to the outbreak". N Engl J Med. 371 (13): 1183–1185. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1409859. PMID 25140856.

- ^ "Sierra Leone: a traditional healer and a funeral". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Salaam-Blyther T (26 August 2014). "The 2014 Ebola Outbreak: International and U.S. Responses" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ Lashley FR, Durham JD, eds. (2007). Emerging infectious diseases trends and issues (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 141. ISBN 978-0826103505. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016.

- ^ Magill AJ, Strickland GT, Maguire JH, Ryan ET, Solomon T, eds. (2013). Hunter's tropical medicine and emerging infectious disease (9th ed.). London; New York: Elsevier. pp. 170–172. ISBN 978-1455740437. OCLC 822525408. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016.

- ^ "Questions and Answers on Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 22 May 2018. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Ebola in Texas: Second Health Care Worker Tests Positive". NBC News. 15 October 2014. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014.

- ^ Jones RM, Brosseau LM (May 2015). "Aerosol transmission of infectious disease". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (Review). 57 (5): 501–508. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000000448. PMID 25816216. S2CID 11166016.

- ^ a b "Transmission of Ebola virus". virology.ws. 27 September 2014. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Weingartl HM, Embury-Hyatt C, Nfon C, Leung A, Smith G, Kobinger G (2012). "Transmission of Ebola virus from pigs to non-human primates". Scientific Reports. 2: 811. Bibcode:2012NatSR...2..811W. doi:10.1038/srep00811. PMC 3498927. PMID 23155478.