Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Threshold potential

View on Wikipedia

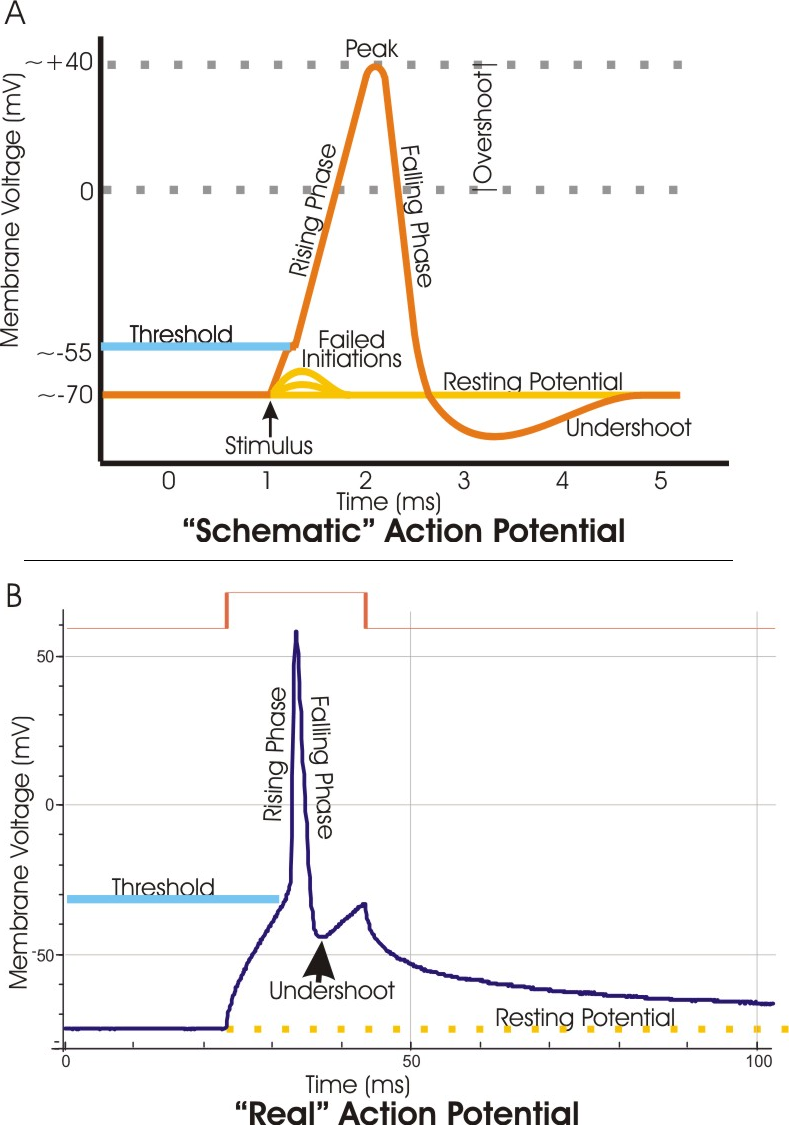

In electrophysiology, the threshold potential is the critical level to which a membrane potential must be depolarized to initiate an action potential. In neuroscience, threshold potentials are necessary to regulate and propagate signaling in both the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS).

Most often, the threshold potential is a membrane potential value between –50 and –55 mV,[1] but can vary based upon several factors. A neuron's resting membrane potential (–70 mV) can be altered to either increase or decrease likelihood of reaching threshold via sodium and potassium ions. An influx of sodium into the cell through open, voltage-gated sodium channels can depolarize the membrane past threshold and thus excite it while an efflux of potassium or influx of chloride can hyperpolarize the cell and thus inhibit threshold from being reached.

Discovery

[edit]Initial experiments revolved around the concept that any electrical change that is brought about in neurons must occur through the action of ions. The German physical chemist Walther Nernst applied this concept in experiments to discover nervous excitability, and concluded that the local excitatory process through a semi-permeable membrane depends upon the ionic concentration. Also, ion concentration was shown to be the limiting factor in excitation. If the proper concentration of ions was attained, excitation would certainly occur.[2] This was the basis for discovering the threshold value.

Along with reconstructing the action potential in the 1950s, Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley were also able to experimentally determine the mechanism behind the threshold for excitation. It is known as the Hodgkin–Huxley model. Through use of voltage clamp techniques on a squid giant axon, they discovered that excitable tissues generally exhibit the phenomenon that a certain membrane potential must be reached in order to fire an action potential. Since the experiment yielded results through the observation of ionic conductance changes, Hodgkin and Huxley used these terms to discuss the threshold potential. They initially suggested that there must be a discontinuity in the conductance of either sodium or potassium, but in reality both conductances tended to vary smoothly along with the membrane potential.[3]

They soon discovered that at threshold potential, the inward and outward currents, of sodium and potassium ions respectively, were exactly equal and opposite. As opposed to the resting membrane potential, the threshold potential's conditions exhibited a balance of currents that were unstable. Instability refers to the fact that any further depolarization activates even more voltage-gated sodium channels, and the incoming sodium depolarizing current overcomes the delayed outward current of potassium.[4] At resting level, on the other hand, the potassium and sodium currents are equal and opposite in a stable manner, where a sudden, continuous flow of ions should not result. The basis is that at a certain level of depolarization, when the currents are equal and opposite in an unstable manner, any further entry of positive charge generates an action potential. This specific value of depolarization (in mV) is otherwise known as the threshold potential.

Physiological function and characteristics

[edit]The threshold value controls whether or not the incoming stimuli are sufficient to generate an action potential. It relies on a balance of incoming inhibitory and excitatory stimuli. The potentials generated by the stimuli are additive, and they may reach threshold depending on their frequency and amplitude. Normal functioning of the central nervous system entails a summation of synaptic inputs made largely onto a neuron's dendritic tree. These local graded potentials, which are primarily associated with external stimuli, reach the axonal initial segment and build until they manage to reach the threshold value.[5] The larger the stimulus, the greater the depolarization, or attempt to reach threshold. The task of depolarization requires several key steps that rely on anatomical factors of the cell. The ion conductances involved depend on the membrane potential and also the time after the membrane potential changes.[6]

Resting membrane potential

[edit]The phospholipid bilayer of the cell membrane is, in itself, highly impermeable to ions. The complete structure of the cell membrane includes many proteins that are embedded in or completely cross the lipid bilayer. Some of those proteins allow for the highly specific passage of ions, ion channels. Leak potassium channels allow potassium to flow through the membrane in response to the disparity in concentrations of potassium inside (high concentration) and outside the cell (low). The loss of positive(+) charges of the potassium(K+) ions from the inside of the cell results in a negative potential there compared to the extracellular surface of the membrane.[7] A much smaller "leak" of sodium(Na+) into the cell results in the actual resting potential, about –70 mV, being less negative than the calculated potential for K+ alone, the equilibrium potential, about –90 mV.[7] The sodium-potassium ATPase is an active transporter within the membrane that pumps potassium (2 ions) back into the cell and sodium (3 ions) out of the cell, maintaining the concentrations of both ions as well as preserving the voltage polarization.

Depolarization

[edit]However, once a stimulus activates the voltage-gated sodium channels to open, positive sodium ions flood into the cell and the voltage increases. This process can also be initiated by ligand or neurotransmitter binding to a ligand-gated channel. More sodium is outside the cell relative to the inside, and the positive charge within the cell propels the outflow of potassium ions through delayed-rectifier voltage-gated potassium channels. Since the potassium channels within the cell membrane are delayed, any further entrance of sodium activates more and more voltage-gated sodium channels. Depolarization above threshold results in an increase in the conductance of Na sufficient for inward sodium movement to swamp outward potassium movement immediately.[3] If the influx of sodium ions fails to reach threshold, then sodium conductance does not increase a sufficient amount to override the resting potassium conductance. In that case, subthreshold membrane potential oscillations are observed in some type of neurons. If successful, the sudden influx of positive charge depolarizes the membrane, and potassium is delayed in re-establishing, or hyperpolarizing, the cell. Sodium influx depolarizes the cell in attempt to establish its own equilibrium potential (about +52 mV) to make the inside of the cell more positive relative to the outside.

Variations

[edit]The value of threshold can vary according to numerous factors. Changes in the ion conductances of sodium or potassium can lead to either a raised or lowered value of threshold. Additionally, the diameter of the axon, density of voltage activated sodium channels, and properties of sodium channels within the axon all affect the threshold value.[8] Typically in the axon or dendrite, there are small depolarizing or hyperpolarizing signals resulting from a prior stimulus. The passive spread of these signals depend on the passive electrical properties of the cell. The signals can only continue along the neuron to cause an action potential further down if they are strong enough to make it past the cell's membrane resistance and capacitance. For example, a neuron with a large diameter has more ionic channels in its membrane than a smaller cell, resulting in a lower resistance to the flow of ionic current. The current spreads quicker in a cell with less resistance, and is more likely to reach the threshold at other portions of the neuron.[3]

The threshold potential has also been shown experimentally to adapt to slow changes in input characteristics by regulating sodium channel density as well as inactivating these sodium channels overall. Hyperpolarization by the delayed-rectifier potassium channels causes a relative refractory period that makes it much more difficult to reach threshold. The delayed-rectifier potassium channels are responsible for the late outward phase of the action potential, where they open at a different voltage stimulus compared to the quickly activated sodium channels. They rectify, or repair, the balance of ions across the membrane by opening and letting potassium flow down its concentration gradient from inside to outside the cell. They close slowly as well, resulting in an outward flow of positive charge that exceeds the balance necessary. It results in excess negativity in the cell, requiring an extremely large stimulus and resulting depolarization to cause a response.

Tracking techniques

[edit]Threshold tracking techniques test nerve excitability, and depend on the properties of axonal membranes and sites of stimulation. They are extremely sensitive to the membrane potential and changes in this potential. These tests can measure and compare a control threshold (or resting threshold) to a threshold produced by a change in the environment, by a preceding single impulse, an impulse train, or a subthreshold current.[9] Measuring changes in threshold can indicate changes in membrane potential, axonal properties, and/or the integrity of the myelin sheath.

Threshold tracking allows for the strength of a test stimulus to be adjusted by a computer in order to activate a defined fraction of the maximal nerve or muscle potential. A threshold tracking experiment consists of a 1-ms stimulus being applied to a nerve in regular intervals.[10] The action potential is recorded downstream from the triggering impulse. The stimulus is automatically decreased in steps of a set percentage until the response falls below the target (generation of an action potential). Thereafter, the stimulus is stepped up or down depending on whether the previous response was lesser or greater than the target response until a resting (or control) threshold has been established. Nerve excitability can then be changed by altering the nerve environment or applying additional currents. Since the value of a single threshold current provides little valuable information because it varies within and between subjects, pairs of threshold measurements, comparing the control threshold to thresholds produced by refractoriness, supernormality, strength-duration time constant or "threshold electrotonus" are more useful in scientific and clinical study.[11]

Tracking threshold has advantages over other electrophysiological techniques, like the constant stimulus method. This technique can track threshold changes within a dynamic range of 200% and in general give more insight into axonal properties than other tests.[12] Also, this technique allows for changes in threshold to be given a quantitative value, which when mathematically converted into a percentage, can be used to compare single fiber and multifiber preparations, different neuronal sites, and nerve excitability in different species.[12]

"Threshold electrotonus"

[edit]A specific threshold tracking technique is threshold electrotonus, which uses the threshold tracking set-up to produce long-lasting subthreshold depolarizing or hyperpolarizing currents within a membrane. Changes in cell excitability can be observed and recorded by creating these long-lasting currents. Threshold decrease is evident during extensive depolarization, and threshold increase is evident with extensive hyperpolarization. With hyperpolarization, there is an increase in the resistance of the internodal membrane due to closure of potassium channels, and the resulting plot "fans out". Depolarization produces has the opposite effect, activating potassium channels, producing a plot that "fans in".[13]

The most important factor determining threshold electrotonus is membrane potential, so threshold electrotonus can also be used as an index of membrane potential. Furthermore, it can be used to identify characteristics of significant medical conditions through comparing the effects of those conditions on threshold potential with the effects viewed experimentally. For example, ischemia and depolarization cause the same "fanning in" effect of the electrotonus waveforms. This observation leads to the conclusion that ischemia may result from over-activation of potassium channels.[14]

Clinical significance

[edit]The role of the threshold potential has been implicated in a clinical context, namely in the functioning of the nervous system itself as well as in the cardiovascular system.

Febrile seizures

[edit]A febrile seizure, or "fever fit", is a convulsion associated with a significant rise in body temperature, occurring most commonly in early childhood. Repeated episodes of childhood febrile seizures are associated with an increased risk of temporal lobe epilepsy in adulthood.[15]

With patch clamp recording, an analogous state was replicated in vitro in rat cortical neurons after induction of febrile body temperatures; a notable decrease in threshold potential was observed. The mechanism for this decrease possibly involves suppression of inhibition mediated by the GABAB receptor with excessive heat exposure.[15]

ALS and diabetes

[edit]Abnormalities in neuronal excitability have been noted in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and diabetes patients. While the mechanism ultimately responsible for the variance differs between the two conditions, tests through a response to ischemia indicate a similar resistance, ironically, to ischemia and resulting paresthesias. As ischemia occurs through inhibition of the sodium-potassium pump, abnormalities in the threshold potential are hence implicated.[12]

Arrhythmia

[edit]Since the 1940s, the concept of diastolic depolarization, or "pacemaker potential", has become established; this mechanism is a characteristic distinctive of cardiac tissue.[16] When the threshold is reached and the resulting action potential fires, a heartbeat results from the interactions; however, when this heartbeat occurs at an irregular time, a potentially serious condition known as arrhythmia may result.

Use of medications

[edit]A variety of drugs can present prolongation of the QT interval as a side effect. Prolongation of this interval is a result of a delay in sodium and calcium channel inactivation; without proper channel inactivation, the threshold potential is reached prematurely and thus arrhythmia tends to result.[17] These drugs, known as pro-arrhythmic agents, include antimicrobials, antipsychotics, methadone, and, ironically, antiarrhythmic agents.[18] The use of such agents is particularly frequent in intensive care units, and special care must be exercised when QT intervals are prolonged in such patients: arrhythmias as a result of prolonged QT intervals include the potentially fatal torsades de pointes, or TdP.[17]

Role of diet

[edit]Diet may be a variable in the risk of arrhythmia. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, found in fish oils and several plant oils,[19] serve a role in the prevention of arrhythmias.[20] By inhibiting the voltage-dependent sodium current, these oils shift the threshold potential to a more positive value; therefore, an action potential requires increased depolarization.[20] Clinically therapeutic use of these extracts remains a subject of research, but a strong correlation is established between regular consumption of fish oil and lower frequency of hospitalization for atrial fibrillation, a severe and increasingly common arrhythmia.[21]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Seifter, Ratner & Sloane 2005, p. 55.

- ^ Rushton 1927, p. 358.

- ^ a b c Nicholls et al. 2012, p. 121.

- ^ Nicholls et al. 2012, p. 122.

- ^ Stuart et al. 1997, p. 127.

- ^ Trautwein 1963, p. 330.

- ^ a b Nicholls et al. 2012, p. 144.

- ^ Trautwein 1963, p. 281.

- ^ Bostock, Cikurel & Burke 1998, p. 137.

- ^ Bostock, Cikurel & Burke 1998, p. 138.

- ^ Burke, Kiernan & Bostock 2001, p. 1576.

- ^ a b c Bostock, Cikurel & Burke 1998, p. 141.

- ^ Burke, Kiernan & Bostock 2001, p. 1581.

- ^ Bostock, Cikurel & Burke 1998, p. 150.

- ^ a b Wang et al. 2011, p. 87.

- ^ Monfredi et al. 2010, p. 1392.

- ^ a b Nelson & Leung 2011, p. 292.

- ^ Nelson & Leung 2011, p. 291.

- ^ "Polyunsaturated Fat". American Heart Association. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ a b Savelieva, Kourliouros & Camm 2010, p. 213.

- ^ Savelieva, Kourliouros & Camm 2010, pp. 213–215.

References

[edit]- Bostock, Hugh; Cikurel, Katia; Burke, David (1998). "Threshold tracking techniques in the study of human peripheral nerve". Muscle & Nerve. 21 (2): 137–158. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199802)21:2<137::AID-MUS1>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 9466589. S2CID 2914214.

- Burke, D; Kiernan, Matthew C; Bostock, Hugh (2001). "Excitability of human axons". Clinical Neurophysiology. 112 (9): 1575–1585. doi:10.1016/S1388-2457(01)00595-8. S2CID 32160313.

- Monfredi, O; Dobrzyński, H; Mondal, T; Boyett, MR; Morris, GM (2010). "The Anatomy and Physiology of the Sinoatrial Node—A Contemporary Review". Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 33 (11): 1392–1406. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02838.x. PMID 20946278. S2CID 22207608.

- Nelson, S; Leung, J (2011). "QTc Prolongation in the Intensive Care Unit: A Review of Offending Agents". AACN Advanced Critical Care. 22 (4): 289–295. doi:10.1097/NCI.0b013e31822db49d. PMID 22064575.

- Nicholls, J. G.; Martin, A. R.; Fuchs, P. A.; Brown, D. A.; Diamond, M. E.; Weisblat, D. A. (2012). From Neuron to Brain (5th ed.). Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc.

- Rushton, W. A. H. (1927). "The effect upon the threshold for nervous excitation of the length of nerve exposed, and the angle between current and nerve". The Journal of Physiology. 63 (4): 357–377. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1927.sp002409. PMC 1514939. PMID 16993895.

- Savelieva, I; Kourliouros, Antonios; Camm, John (2010). "Primary and secondary prevention of atrial fibrillation with statins and polyunsaturated fatty acids: review of evidence and clinical relevance". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 381 (3): 207–219. doi:10.1007/s00210-009-0468-y. PMID 19937318. S2CID 6003098.

- Seifter, Julian; Ratner, Austin; Sloane, David (2005). Concepts in Medical Physiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0781744898.

- Stuart, G; Spruston, N; Sakmann, B; Häusser, M (1997). "Action potential initiation and backpropagation in neurons of the mammalian CNS" (PDF). Trends in Neurosciences. 20 (3): 125–131. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10075-8. PMID 9061867. S2CID 889625.

- Trautwein, W (1963). "Generation and conduction of impulses in the heart as affected by drugs". Pharmacological Reviews. 15 (2): 277–332.

- Wang, Y; Qin, J; Han, Y; Cai, J; Xing, G (2011). "Hyperthermia induces epileptiform discharges in cultured rat cortical neurons". Brain Research. 1417: 87–102. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2011.08.027. PMID 21907327. S2CID 8431090.

External links

[edit]- Nosek, Thomas M. "Section 1/1ch4/s1ch4_8". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24.

- Description at cameron.edu

- Diagram at nih.gov[dead link]