Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mathematical model

View on WikipediaA mathematical model is an abstract description of a concrete system using mathematical concepts and language. The process of developing a mathematical model is termed mathematical modeling. Mathematical models are used in many fields, including applied mathematics, natural sciences, social sciences[1][2] and engineering. In particular, the field of operations research studies the use of mathematical modelling and related tools to solve problems in business or military operations. A model may help to characterize a system by studying the effects of different components, which may be used to make predictions about behavior or solve specific problems.

Elements of a mathematical model

[edit]Mathematical models can take many forms, including dynamical systems, statistical models, differential equations, or game theoretic models. These and other types of models can overlap, with a given model involving a variety of abstract structures. In many cases, the quality of a scientific field depends on how well the mathematical models developed on the theoretical side agree with results of repeatable experiments. Lack of agreement between theoretical mathematical models and experimental measurements often leads to important advances as better theories are developed. In the physical sciences, a traditional mathematical model contains most of the following elements:

- Governing equations

- Supplementary sub-models

- Defining equations

- Constitutive equations

- Assumptions and constraints

Classifications

[edit]Mathematical models are of different types:

Linear vs. nonlinear

[edit]If all the operators in a mathematical model exhibit linearity, the resulting mathematical model is defined as linear. All other models are considered nonlinear. The definition of linearity and nonlinearity is dependent on context, and linear models may have nonlinear expressions in them. For example, in a statistical linear model, it is assumed that a relationship is linear in the parameters, but it may be nonlinear in the predictor variables. Similarly, a differential equation is said to be linear if it can be written with linear differential operators, but it can still have nonlinear expressions in it. In a mathematical programming model, if the objective functions and constraints are represented entirely by linear equations, then the model is regarded as a linear model. If one or more of the objective functions or constraints are represented with a nonlinear equation, then the model is known as a nonlinear model.

Linear structure implies that a problem can be decomposed into simpler parts that can be treated independently or analyzed at a different scale, and therefore that the results will remain valid if the initial is recomposed or rescaled.

Nonlinearity, even in fairly simple systems, is often associated with phenomena such as chaos and irreversibility. Although there are exceptions, nonlinear systems and models tend to be more difficult to study than linear ones. A common approach to nonlinear problems is linearization, but this can be problematic if one is trying to study aspects such as irreversibility, which are strongly tied to nonlinearity.

Static vs. dynamic

[edit]A dynamic model accounts for time-dependent changes in the state of the system, while a static (or steady-state) model calculates the system in equilibrium, and thus is time-invariant. Dynamic models are typically represented by differential equations or difference equations.

Explicit vs. implicit

[edit]If all of the input parameters of the overall model are known, and the output parameters can be calculated by a finite series of computations, the model is said to be explicit. But sometimes it is the output parameters which are known, and the corresponding inputs must be solved for by an iterative procedure, such as Newton's method or Broyden's method. In such a case the model is said to be implicit. For example, a jet engine's physical properties such as turbine and nozzle throat areas can be explicitly calculated given a design thermodynamic cycle (air and fuel flow rates, pressures, and temperatures) at a specific flight condition and power setting, but the engine's operating cycles at other flight conditions and power settings cannot be explicitly calculated from the constant physical properties.

Discrete vs. continuous

[edit]A discrete model treats objects as discrete, such as the particles in a molecular model or the states in a statistical model; while a continuous model represents the objects in a continuous manner, such as the velocity field of fluid in pipe flows, temperatures and stresses in a solid, and electric field that applies continuously over the entire model due to a point charge.

Deterministic vs. probabilistic (stochastic)

[edit]A deterministic model is one in which every set of variable states is uniquely determined by parameters in the model and by sets of previous states of these variables; therefore, a deterministic model always performs the same way for a given set of initial conditions. Conversely, in a stochastic model—usually called a "statistical model"—randomness is present, and variable states are not described by unique values, but rather by probability distributions.

Deductive, inductive, or floating

[edit]A deductive model is a logical structure based on a theory. An inductive model arises from empirical findings and generalization from them. If a model rests on neither theory nor observation, it may be described as a 'floating' model. Application of mathematics in social sciences outside of economics has been criticized for unfounded models.[3] Application of catastrophe theory in science has been characterized as a floating model.[4]

Strategic vs. non-strategic

[edit]Models used in game theory are distinct in the sense that they model agents with incompatible incentives, such as competing species or bidders in an auction. Strategic models assume that players are autonomous decision makers who rationally choose actions that maximize their objective function. A key challenge of using strategic models is defining and computing solution concepts such as the Nash equilibrium. An interesting property of strategic models is that they separate reasoning about rules of the game from reasoning about behavior of the players.[5]

Construction

[edit]In business and engineering, mathematical models may be used to maximize a certain output. The system under consideration will require certain inputs. The system relating inputs to outputs depends on other variables too: decision variables, state variables, exogenous variables, and random variables. Decision variables are sometimes known as independent variables. Exogenous variables are sometimes known as parameters or constants. The variables are not independent of each other as the state variables are dependent on the decision, input, random, and exogenous variables. Furthermore, the output variables are dependent on the state of the system (represented by the state variables).

Objectives and constraints of the system and its users can be represented as functions of the output variables or state variables. The objective functions will depend on the perspective of the model's user. Depending on the context, an objective function is also known as an index of performance, as it is some measure of interest to the user. Although there is no limit to the number of objective functions and constraints a model can have, using or optimizing the model becomes more involved (computationally) as the number increases. For example, economists often apply linear algebra when using input–output models. Complicated mathematical models that have many variables may be consolidated by use of vectors where one symbol represents several variables.

A priori information

[edit]

Mathematical modeling problems are often classified into black box or white box models, according to how much a priori information on the system is available. A black-box model is a system of which there is no a priori information available. A white-box model (also called glass box or clear box) is a system where all necessary information is available. Practically all systems are somewhere between the black-box and white-box models, so this concept is useful only as an intuitive guide for deciding which approach to take.

Usually, it is preferable to use as much a priori information as possible to make the model more accurate. Therefore, the white-box models are usually considered easier, because if you have used the information correctly, then the model will behave correctly. Often the a priori information comes in forms of knowing the type of functions relating different variables. For example, if we make a model of how a medicine works in a human system, we know that usually the amount of medicine in the blood is an exponentially decaying function, but we are still left with several unknown parameters; how rapidly does the medicine amount decay, and what is the initial amount of medicine in blood? This example is therefore not a completely white-box model. These parameters have to be estimated through some means before one can use the model.

In black-box models, one tries to estimate both the functional form of relations between variables and the numerical parameters in those functions. Using a priori information we could end up, for example, with a set of functions that probably could describe the system adequately. If there is no a priori information we would try to use functions as general as possible to cover all different models. An often used approach for black-box models are neural networks which usually do not make assumptions about incoming data. Alternatively, the NARMAX (Nonlinear AutoRegressive Moving Average model with eXogenous inputs) algorithms which were developed as part of nonlinear system identification[6] can be used to select the model terms, determine the model structure, and estimate the unknown parameters in the presence of correlated and nonlinear noise. The advantage of NARMAX models compared to neural networks is that NARMAX produces models that can be written down and related to the underlying process, whereas neural networks produce an approximation that is opaque.

Subjective information

[edit]Sometimes it is useful to incorporate subjective information into a mathematical model. This can be done based on intuition, experience, or expert opinion, or based on convenience of mathematical form. Bayesian statistics provides a theoretical framework for incorporating such subjectivity into a rigorous analysis: we specify a prior probability distribution (which can be subjective), and then update this distribution based on empirical data.

An example of when such approach would be necessary is a situation in which an experimenter bends a coin slightly and tosses it once, recording whether it comes up heads, and is then given the task of predicting the probability that the next flip comes up heads. After bending the coin, the true probability that the coin will come up heads is unknown; so the experimenter would need to make a decision (perhaps by looking at the shape of the coin) about what prior distribution to use. Incorporation of such subjective information might be important to get an accurate estimate of the probability.

Complexity

[edit]In general, model complexity involves a trade-off between simplicity and accuracy of the model. Occam's razor is a principle particularly relevant to modeling, its essential idea being that among models with roughly equal predictive power, the simplest one is the most desirable. While added complexity usually improves the realism of a model, it can make the model difficult to understand and analyze, and can also pose computational problems, including numerical instability. Thomas Kuhn argues that as science progresses, explanations tend to become more complex before a paradigm shift offers radical simplification.[7]

For example, when modeling the flight of an aircraft, we could embed each mechanical part of the aircraft into our model and would thus acquire an almost white-box model of the system. However, the computational cost of adding such a huge amount of detail would effectively inhibit the usage of such a model. Additionally, the uncertainty would increase due to an overly complex system, because each separate part induces some amount of variance into the model. It is therefore usually appropriate to make some approximations to reduce the model to a sensible size. Engineers often can accept some approximations in order to get a more robust and simple model. For example, Newton's classical mechanics is an approximated model of the real world. Still, Newton's model is quite sufficient for most ordinary-life situations, that is, as long as particle speeds are well below the speed of light, and we study macro-particles only. Note that better accuracy does not necessarily mean a better model. Statistical models are prone to overfitting which means that a model is fitted to data too much and it has lost its ability to generalize to new events that were not observed before.

Training, tuning, and fitting

[edit]Any model which is not pure white-box contains some parameters that can be used to fit the model to the system it is intended to describe. If the modeling is done by an artificial neural network or other machine learning, the optimization of parameters is called training, while the optimization of model hyperparameters is called tuning and often uses cross-validation.[8] In more conventional modeling through explicitly given mathematical functions, parameters are often determined by curve fitting.[citation needed]

Evaluation and assessment

[edit]A crucial part of the modeling process is the evaluation of whether or not a given mathematical model describes a system accurately. This question can be difficult to answer as it involves several different types of evaluation.

Prediction of empirical data

[edit]Usually, the easiest part of model evaluation is checking whether a model predicts experimental measurements or other empirical data not used in the model development. In models with parameters, a common approach is to split the data into two disjoint subsets: training data and verification data. The training data are used to estimate the model parameters. An accurate model will closely match the verification data even though these data were not used to set the model's parameters. This practice is referred to as cross-validation in statistics.

Defining a metric to measure distances between observed and predicted data is a useful tool for assessing model fit. In statistics, decision theory, and some economic models, a loss function plays a similar role. While it is rather straightforward to test the appropriateness of parameters, it can be more difficult to test the validity of the general mathematical form of a model. In general, more mathematical tools have been developed to test the fit of statistical models than models involving differential equations. Tools from nonparametric statistics can sometimes be used to evaluate how well the data fit a known distribution or to come up with a general model that makes only minimal assumptions about the model's mathematical form.

Scope of the model

[edit]Assessing the scope of a model, that is, determining what situations the model is applicable to, can be less straightforward. If the model was constructed based on a set of data, one must determine for which systems or situations the known data is a "typical" set of data. The question of whether the model describes well the properties of the system between data points is called interpolation, and the same question for events or data points outside the observed data is called extrapolation.

As an example of the typical limitations of the scope of a model, in evaluating Newtonian classical mechanics, we can note that Newton made his measurements without advanced equipment, so he could not measure properties of particles traveling at speeds close to the speed of light. Likewise, he did not measure the movements of molecules and other small particles, but macro particles only. It is then not surprising that his model does not extrapolate well into these domains, even though his model is quite sufficient for ordinary life physics.

Philosophical considerations

[edit]Many types of modeling implicitly involve claims about causality. This is usually (but not always) true of models involving differential equations. As the purpose of modeling is to increase our understanding of the world, the validity of a model rests not only on its fit to empirical observations, but also on its ability to extrapolate to situations or data beyond those originally described in the model. One can think of this as the differentiation between qualitative and quantitative predictions. One can also argue that a model is worthless unless it provides some insight which goes beyond what is already known from direct investigation of the phenomenon being studied.

An example of such criticism is the argument that the mathematical models of optimal foraging theory do not offer insight that goes beyond the common-sense conclusions of evolution and other basic principles of ecology.[9] It should also be noted that while mathematical modeling uses mathematical concepts and language, it is not itself a branch of mathematics and does not necessarily conform to any mathematical logic, but is typically a branch of some science or other technical subject, with corresponding concepts and standards of argumentation.[10]

Significance in the natural sciences

[edit]Mathematical models are of great importance in the natural sciences, particularly in physics. Physical theories are almost invariably expressed using mathematical models. Throughout history, more and more accurate mathematical models have been developed. Newton's laws accurately describe many everyday phenomena, but at certain limits theory of relativity and quantum mechanics must be used.

It is common to use idealized models in physics to simplify things. Massless ropes, point particles, ideal gases and the particle in a box are among the many simplified models used in physics. The laws of physics are represented with simple equations such as Newton's laws, Maxwell's equations and the Schrödinger equation. These laws are a basis for making mathematical models of real situations. Many real situations are very complex and thus modeled approximately on a computer, a model that is computationally feasible to compute is made from the basic laws or from approximate models made from the basic laws. For example, molecules can be modeled by molecular orbital models that are approximate solutions to the Schrödinger equation. In engineering, physics models are often made by mathematical methods such as finite element analysis.

Different mathematical models use different geometries that are not necessarily accurate descriptions of the geometry of the universe. Euclidean geometry is much used in classical physics, while special relativity and general relativity are examples of theories that use geometries which are not Euclidean.

Some applications

[edit]Often when engineers analyze a system to be controlled or optimized, they use a mathematical model. In analysis, engineers can build a descriptive model of the system as a hypothesis of how the system could work, or try to estimate how an unforeseeable event could affect the system. Similarly, in control of a system, engineers can try out different control approaches in simulations.

A mathematical model usually describes a system by a set of variables and a set of equations that establish relationships between the variables. Variables may be of many types; real or integer numbers, Boolean values or strings, for example. The variables represent some properties of the system, for example, the measured system outputs often in the form of signals, timing data, counters, and event occurrence. The actual model is the set of functions that describe the relations between the different variables.

Examples

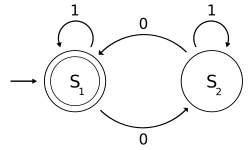

[edit]- One of the popular examples in computer science is the mathematical models of various machines, an example is the deterministic finite automaton (DFA) which is defined as an abstract mathematical concept, but due to the deterministic nature of a DFA, it is implementable in hardware and software for solving various specific problems. For example, the following is a DFA M with a binary alphabet, which requires that the input contains an even number of 0s:

- where

- and

- is defined by the following state-transition table:

- where

- 01

S1 S2

- The state represents that there has been an even number of 0s in the input so far, while signifies an odd number. A 1 in the input does not change the state of the automaton. When the input ends, the state will show whether the input contained an even number of 0s or not. If the input did contain an even number of 0s, will finish in state an accepting state, so the input string will be accepted.

- The language recognized by is the regular language given by the regular expression 1*( 0 (1*) 0 (1*) )*, where "*" is the Kleene star, e.g., 1* denotes any non-negative number (possibly zero) of symbols "1".

- Many everyday activities carried out without a thought are uses of mathematical models. A geographical map projection of a region of the earth onto a small, plane surface is a model which can be used for many purposes such as planning travel.[11]

- Another simple activity is predicting the position of a vehicle from its initial position, direction and speed of travel, using the equation that distance traveled is the product of time and speed. This is known as dead reckoning when used more formally. Mathematical modeling in this way does not necessarily require formal mathematics; animals have been shown to use dead reckoning.[12][13]

- Population Growth. A simple (though approximate) model of population growth is the Malthusian growth model. A slightly more realistic and largely used population growth model is the logistic function, and its extensions.

- Model of a particle in a potential-field. In this model we consider a particle as being a point of mass which describes a trajectory in space which is modeled by a function giving its coordinates in space as a function of time. The potential field is given by a function and the trajectory, that is a function is the solution of the differential equation: that can be written also as

- Note this model assumes the particle is a point mass, which is certainly known to be false in many cases in which we use this model; for example, as a model of planetary motion.

- Model of rational behavior for a consumer. In this model we assume a consumer faces a choice of commodities labeled each with a market price The consumer is assumed to have an ordinal utility function (ordinal in the sense that only the sign of the differences between two utilities, and not the level of each utility, is meaningful), depending on the amounts of commodities consumed. The model further assumes that the consumer has a budget which is used to purchase a vector in such a way as to maximize The problem of rational behavior in this model then becomes a mathematical optimization problem, that is: subject to: This model has been used in a wide variety of economic contexts, such as in general equilibrium theory to show existence and Pareto efficiency of economic equilibria.

- Neighbour-sensing model is a model that explains the mushroom formation from the initially chaotic fungal network.

- In computer science, mathematical models may be used to simulate computer networks.

- In mechanics, mathematical models may be used to analyze the movement of a rocket model.

See also

[edit]- Agent-based model

- All models are wrong

- Cliodynamics

- Computer simulation

- Conceptual model

- Decision engineering

- Grey box model

- International Mathematical Modeling Challenge

- Mathematical biology

- Mathematical diagram

- Mathematical economics

- Mathematical modelling of infectious disease

- Mathematical finance

- Mathematical psychology

- Mathematical sociology

- Microscale and macroscale models

- Model inversion

- Resilience (mathematics)

- Scientific model

- Sensitivity analysis

- Spherical cow

- Statistical model

- Surrogate model

- System identification

References

[edit]- ^ Saltelli, Andrea; et al. (June 2020). "Five ways to ensure that models serve society: a manifesto". Nature. 582 (7813): 482–484. Bibcode:2020Natur.582..482S. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01812-9. hdl:1885/219031. PMID 32581374.

- ^ Kornai, András (2008). Mathematical linguistics. Advanced information and knowledge processing. London: Springer. ISBN 978-1-84628-985-9.

- ^ Andreski, Stanislav (1972). Social Sciences as Sorcery. St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-14-021816-5.

- ^ Truesdell, Clifford (1984). An Idiot's Fugitive Essays on Science. Springer. pp. 121–7. ISBN 3-540-90703-3.

- ^ Li, C., Xing, Y., He, F., & Cheng, D. (2018). A Strategic Learning Algorithm for State-based Games. ArXiv.

- ^ Billings S.A. (2013), Nonlinear System Identification: NARMAX Methods in the Time, Frequency, and Spatio-Temporal Domains, Wiley.

- ^ "Thomas Kuhn". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. August 13, 2004. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ Thornton, Chris. "Machine Learning Lecture". Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ Pyke, G. H. (1984). "Optimal Foraging Theory: A Critical Review". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 15 (1): 523–575. Bibcode:1984AnRES..15..523P. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.15.110184.002515.

- ^ Edwards, Dilwyn; Hamson, Mike (2007). Guide to Mathematical Modelling (2 ed.). New York: Industrial Press Inc. ISBN 978-0-8311-3337-5.

- ^ "GIS Definitions of Terminology M-P". LAND INFO Worldwide Mapping. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ Gallistel (1990). The Organization of Learning. Cambridge: The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-07113-4.

- ^ Whishaw, I. Q.; Hines, D. J.; Wallace, D. G. (2001). "Dead reckoning (path integration) requires the hippocampal formation: Evidence from spontaneous exploration and spatial learning tasks in light (allothetic) and dark (idiothetic) tests". Behavioural Brain Research. 127 (1–2): 49–69. doi:10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00359-X. PMID 11718884. S2CID 7897256.

Further reading

[edit]Books

[edit]- Aris, Rutherford [ 1978 ] ( 1994 ). Mathematical Modelling Techniques, New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-68131-9

- Bender, E.A. [ 1978 ] ( 2000 ). An Introduction to Mathematical Modeling, New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-41180-X

- Gary Chartrand (1977) Graphs as Mathematical Models, Prindle, Webber & Schmidt ISBN 0871502364

- Dubois, G. (2018) "Modeling and Simulation", Taylor & Francis, CRC Press.

- Gershenfeld, N. (1998) The Nature of Mathematical Modeling, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-57095-6 .

- Lin, C.C. & Segel, L.A. ( 1988 ). Mathematics Applied to Deterministic Problems in the Natural Sciences, Philadelphia: SIAM. ISBN 0-89871-229-7

- Models as Mediators: Perspectives on Natural and Social Science edited by Mary S. Morgan and Margaret Morrison, 1999.[1]

- Mary S. Morgan The World in the Model: How Economists Work and Think, 2012.[2]

Specific applications

[edit]- Papadimitriou, Fivos. (2010). Mathematical Modelling of Spatial-Ecological Complex Systems: an Evaluation. Geography, Environment, Sustainability 1(3), 67–80. doi:10.24057/2071-9388-2010-3-1-67-80

- Peierls, R. (1980). "Model-making in physics". Contemporary Physics. 21: 3–17. Bibcode:1980ConPh..21....3P. doi:10.1080/00107518008210938.

- An Introduction to Infectious Disease Modelling by Emilia Vynnycky and Richard G White.

External links

[edit]General reference

- Patrone, F. Introduction to modeling via differential equations, with critical remarks.

- Plus teacher and student package: Mathematical Modelling. Brings together all articles on mathematical modeling from Plus Magazine, the online mathematics magazine produced by the Millennium Mathematics Project at the University of Cambridge.

Philosophical

- Frigg, R. and S. Hartmann, Models in Science, in: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, (Spring 2006 Edition)

- Griffiths, E. C. (2010) What is a model?

- ^ Morgan MS, Morrison M, eds. (November 28, 1999). Models as Mediators: Perspectives on Natural and Social Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65097-7.

- ^ Morgan MS (September 17, 2012). The World in the Model: How Economists Work and Think. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00297-5.

Mathematical model

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Purpose

A mathematical model is an abstract representation of a real-world system, process, or phenomenon, expressed through mathematical concepts such as variables, equations, functions, and relationships that capture its essential features to describe, explain, or predict behavior.[10] This representation simplifies complexity by focusing on key elements while abstracting away irrelevant details, allowing for systematic analysis.[11] Unlike empirical observations, it provides a formalized structure that can be manipulated mathematically to reveal underlying patterns.[1] The primary purposes of mathematical models include facilitating a deeper understanding of complex phenomena by breaking them into analyzable components, enabling simulations of scenarios that would be impractical or costly to test in reality, supporting optimization of systems for efficiency or performance, and aiding in hypothesis testing through predictive validation.[12] For instance, they allow researchers to forecast outcomes in fields like epidemiology or engineering without physical trials, thereby informing decision-making and policy.[13] By quantifying relationships, these models bridge theoretical insights with practical applications, enhancing predictive accuracy and exploratory power.[14] Mathematical models differ from physical models, which are tangible, scaled replicas of systems such as wind tunnel prototypes for aircraft design, as the former rely on symbolic and computational abstractions rather than material constructions.[15] They also contrast with conceptual models, which typically use qualitative diagrams, flowcharts, or verbal descriptions to outline system structures without incorporating quantitative equations or variables.[16] This distinction underscores the mathematical model's emphasis on precision and computability over visualization or physical mimicry.[17] The basic workflow for developing and applying a mathematical model begins with problem identification and information gathering to define the system's scope, followed by model formulation, analysis through solving or simulation, and interpretation of results to draw conclusions or recommendations for real-world use.[5] This iterative process ensures the model aligns with observed data while remaining adaptable to new insights, though classifications such as linear versus nonlinear may influence the approach based on system complexity.[18]Key Elements

A mathematical model is constructed from core components that define its structure and behavior. These include variables, which represent the quantities of interest; parameters, which are fixed values influencing the model's dynamics; relations, typically expressed as equations or inequalities that link variables and parameters; and, for time-dependent or spatially varying models, initial or boundary conditions that specify starting states or constraints at boundaries.[19] Variables are categorized as independent, serving as inputs that can be controlled or observed (such as time or external forces), and dependent, representing outputs that the model predicts or explains (like position or population size).[5] Parameters, in contrast, are constants within the model that may require estimation from data, such as growth rates or coefficients, and remain unchanged during simulations unless calibrated.[16] Relations form the mathematical backbone, often as systems of equations that govern how variables evolve, while initial conditions provide values at the outset (e.g., initial population) and boundary conditions delimit the domain (e.g., fixed ends in a vibrating string).[20] Assumptions underpin these components by introducing necessary simplifications to make the real-world phenomenon tractable mathematically. These idealizations, such as assuming constant friction in mechanical systems or negligible external influences, reduce complexity but must be justified to ensure model validity; they explicitly state what is held true or approximated, allowing for later sensitivity analysis. By clarifying these assumptions during formulation, modelers identify potential limitations and align the representation with empirical evidence.[21] Mathematical models can take various representation forms to suit the problem's nature, including algebraic equations for static balances, differential equations for continuous changes over time or space, functional mappings for input-output relations, graphs for discrete networks or relationships, and matrices for linear systems or multidimensional data.[22] These forms enable analytical solutions, numerical computation, or visualization, with the choice depending on the underlying assumptions and computational needs. A general structure for many models is encapsulated in the form , where denotes the independent variables or inputs, the parameters, and the dependent variables or outputs; this framework highlights how inputs and fixed values combine through the function (often an equation or system thereof) to produce predictions, incorporating any initial or boundary conditions as needed.[23]Historical Development

The origins of mathematical modeling trace back to ancient civilizations, where early efforts to quantify and predict natural events laid foundational principles. In Babylonian astronomy around 2000 BCE, scholars employed algebraic and geometric techniques to model celestial movements, using clay tablets to record predictive algorithms for lunar eclipses and planetary positions based on arithmetic series and linear functions.[24] These models represented some of the earliest systematic applications of mathematics to empirical observations, emphasizing predictive accuracy over explanatory theory.[25] Building on these foundations, ancient Greek mathematicians advanced modeling through rigorous geometric frameworks during the Classical period (c. 600–300 BCE). Euclid's Elements (c. 300 BCE) formalized axiomatic geometry as a modeling tool for spatial relationships, enabling deductive proofs of properties like congruence and similarity that influenced later physical models.[26] Archimedes extended this by applying geometric methods to model mechanical systems, such as levers and buoyancy in his work On Floating Bodies, integrating mathematics with engineering principles to simulate real-world dynamics.[26] These contributions shifted modeling toward logical deduction, establishing geometry as a cornerstone for describing natural forms and motions. During the Renaissance and Enlightenment, mathematical modeling evolved to incorporate empirical data and dynamical laws, particularly in astronomy and physics. Johannes Kepler's laws of planetary motion, published between 1609 and 1619 in works like Astronomia Nova, provided empirical models describing elliptical orbits and areal velocities, derived from Tycho Brahe's observations and marking a transition to data-driven heliocentric frameworks.[27] Isaac Newton's Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687) synthesized these into a universal gravitational model, using differential calculus to formulate laws of motion and attraction as predictive equations for celestial and terrestrial phenomena.[28] This era's emphasis on mechanistic explanations unified disparate observations under mathematical universality, paving the way for classical physics. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, mathematical modeling expanded through the development of differential equations and statistical methods, enabling the representation of continuous change and uncertainty. Pierre-Simon Laplace and Joseph Fourier advanced partial differential equations in the early 1800s, with Laplace's work on celestial mechanics (Mécanique Céleste, 1799–1825) modeling gravitational perturbations and Fourier's heat equation (1822) describing diffusion processes via series expansions.[24] Concurrently, statistical models emerged, as Carl Friedrich Gauss introduced the least squares method (1809) for error estimation in astronomical data, and Karl Pearson developed correlation and regression techniques in the late 1800s, formalizing probabilistic modeling for biological and social phenomena.[24] Ludwig von Bertalanffy's General System Theory (1968) further integrated these tools into holistic frameworks, using differential equations to model open systems in biology and beyond, emphasizing interconnectedness over isolated components.[29] A pivotal shift from deterministic to probabilistic modeling occurred in the 1920s with quantum mechanics, where Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger introduced inherently stochastic frameworks, such as the uncertainty principle and wave equations, challenging classical predictability and incorporating probability distributions into physical models.[24] The mid-20th century saw another transformation with the advent of computational modeling in the 1940s, exemplified by the ENIAC computer (1945), which enabled numerical simulations of complex systems like ballistic trajectories and nuclear reactions through iterative algorithms.[30] This analog-to-digital transition accelerated in the 1950s, as electronic digital computers replaced mechanical analogs, allowing scalable solutions to nonlinear equations previously intractable by hand.[30] In the modern era since the 2000s, mathematical modeling has increasingly incorporated computational paradigms like agent-based simulations and machine learning. Agent-based models, popularized through frameworks like NetLogo (1999 onward), simulate emergent behaviors in complex systems such as economies and ecosystems by modeling individual interactions probabilistically.[31] Machine learning models, driven by advances in neural networks and deep learning (e.g., convolutional networks post-2012), have revolutionized predictive modeling by learning patterns from data without explicit programming, applied across fields from image recognition to climate forecasting.[32] These developments reflect ongoing paradigm shifts toward data-intensive, adaptive models that handle vast complexity through algorithmic efficiency.Classifications

Linear versus Nonlinear

In mathematical modeling, a linear model is characterized by the superposition principle, which states that the response to a linear combination of inputs is the same linear combination of the individual responses, and homogeneity, where scaling the input scales the output proportionally.[33][34] These properties ensure that the model's behavior remains predictable and scalable without emergent interactions. Common forms include the static algebraic equation , where is a matrix of coefficients, the vector of unknowns, and a constant vector, or the dynamic state-space representation , used in systems with inputs .[35][36] In contrast, nonlinear models violate these principles due to interactions among variables that produce outputs not proportional to inputs, often leading to complex behaviors such as multiple equilibria or sensitivity to initial conditions. For instance, a simple nonlinear function like yields outputs that grow disproportionately with input magnitude, while coupled nonlinear differential equations, such as the Lorenz system , , , exhibit chaotic attractors for certain parameters.[37] The mathematical properties of linearity facilitate exact analytical solutions, such as through matrix inversion or eigenvalue decomposition for systems like , enabling precise predictions without computational iteration. Nonlinearity, however, often precludes closed-form solutions, resulting in phenomena like bifurcations—abrupt qualitative changes in behavior as parameters vary—and chaos, where small perturbations amplify into large differences, necessitating numerical approximations such as Runge-Kutta methods or perturbation expansions.[38][39] Linear models offer advantages in solvability and computational efficiency, making them ideal for initial approximations or systems where interactions are negligible, though they may oversimplify realities involving thresholds or feedbacks, leading to inaccuracies in complex scenarios. Nonlinear models, conversely, provide greater realism by capturing disproportionate responses, such as exponential growth saturation in population dynamics, but at the cost of increased analytical difficulty and reliance on simulations, which can introduce errors or require high computational resources.[40][41]Static versus Dynamic

Mathematical models are classified as static or dynamic based on their treatment of time. Static models describe a system at a fixed point in time, assuming equilibrium or steady-state conditions without considering temporal evolution.[42][43] In contrast, dynamic models incorporate time as an explicit variable, capturing how the system evolves over periods.[44][16] This distinction is fundamental in fields like engineering and physics, where static models suffice for instantaneous snapshots, while dynamic models are essential for predicting trajectories.[45] Static models typically rely on algebraic equations that relate variables without time derivatives, enabling analysis of balanced states such as input-output relationships in steady conditions. For instance, a simple linear static model might take the form , where represents the output, the input, the slope, and the intercept, often used in economic equilibrium analyses or structural load distributions.[46] These models provide snapshots of system behavior, like mass balance equations in chemical processes where inflows equal outflows at equilibrium.[43] They are computationally simpler and ideal for systems where time-dependent changes are negligible. Dynamic models, on the other hand, employ time-dependent formulations such as ordinary differential equations to simulate evolution. A general form is , which describes the rate of change of a variable as a function of itself and time , commonly applied in population dynamics or mechanical vibrations.[47] Discrete-time variants use difference equations like , tracking sequential updates in systems such as iterative algorithms or sampled data processes.[48] These models reveal behaviors like trajectories over time and stability, where for linear systems, eigenvalues of the system matrix determine whether perturbations decay (stable) or grow (unstable).[49] Static models can approximate dynamic ones when changes occur slowly relative to the observation scale, treating the system as quasi-static to simplify analysis without losing essential insights.[50] For example, in control systems with gradual inputs, a static linearization around an operating point provides a reasonable steady-state prediction. Many dynamic models are linear for small perturbations, facilitating such approximations.[51][52]Discrete versus Continuous

Mathematical models are classified as discrete or continuous based on the nature of their variables and the domains over which they operate. Discrete models describe systems where variables take on values from finite or countable sets, often evolving through distinct steps or iterations, making them suitable for representing phenomena with inherent discontinuities, such as integer counts or sequential events. In contrast, continuous models treat variables as assuming values from uncountable, infinite domains, typically real numbers, and describe smooth changes over time or space. This distinction fundamentally affects the mathematical tools used: discrete models rely on difference equations and combinatorial methods, while continuous models employ differential equations and integral calculus.[53] A canonical example of a discrete model is the logistic map, which models population growth in discrete time steps using the difference equation , where represents the population at generation , is the growth rate, and the term accounts for density-dependent limitations. This model, popularized by ecologist Robert May, exhibits complex behaviors like chaos for certain values, highlighting how discrete iterations can produce intricate dynamics from simple rules. Conversely, the continuous logistic equation, originally formulated by Pierre-François Verhulst, describes population growth via the ordinary differential equation , where is the population at time , is the intrinsic growth rate, and is the carrying capacity; solutions approach sigmoidally, capturing smooth, gradual adjustments in continuous time./08%3A_Introduction_to_Differential_Equations/8.04%3A_The_Logistic_Equation) These examples illustrate how discrete models approximate generational or stepwise processes, while continuous ones model fluid, ongoing changes. Conversions between discrete and continuous models are common in practice. Discretization transforms continuous models into discrete ones for computational purposes, often using the Euler method, which approximates the solution to by the forward difference , where is the time step; for the logistic equation, this yields , enabling numerical simulations on digital computers despite introducing approximation errors that grow with larger .[54] In the opposite direction, continuum limits derive continuous models from discrete ones by taking limits as the step size approaches zero or the grid refines, such as passing from lattice models to partial differential equations in physics, where macroscopic behavior emerges from microscopic discrete interactions.[55] The choice between discrete and continuous models depends on the system's characteristics and modeling goals. Discrete models are preferred for digital simulations, where computations occur in finite steps, and for combinatorial systems like networks or queues, as they align naturally with countable states and avoid the need for infinite precision.[56] Continuous models, however, excel in representing smooth physical processes, such as fluid dynamics or heat diffusion, where variables evolve gradually without abrupt jumps, allowing analytical solutions via calculus that reveal underlying principles like conservation laws.[57] Most dynamic models can be formulated in either framework, with the selection guided by whether the phenomenon's granularity matches discrete events or continuous flows.[58]Deterministic versus Stochastic

Mathematical models are broadly classified into deterministic and stochastic categories based on whether they account for randomness in the system being modeled. Deterministic models assume that the system's behavior is fully predictable given the initial conditions and parameters, producing a unique solution or trajectory for any set of inputs.[59] In these models, there is no inherent variability or uncertainty; the output is fixed and repeatable under identical conditions.[60] A classic example is the exponential growth model used in population dynamics, where the population size at time evolves according to the differential equation , with solution , where is the initial population and is the growth rate.[61] This model yields a precise, unchanging trajectory, making it suitable for systems without external perturbations. In contrast, stochastic models incorporate randomness to represent uncertainty or variability in the system, often through random variables or probabilistic processes that lead to multiple possible outcomes from the same initial conditions.[42] These models are essential for capturing noise, fluctuations, or unpredictable events that deterministic approaches overlook.[62] A prominent example is geometric Brownian motion, a stochastic process frequently applied in financial modeling to describe asset prices, governed by the stochastic differential equation , where is the drift, is the volatility, and is a Wiener process representing random fluctuations.[63] Unlike deterministic models, solutions here involve probability distributions, such as log-normal for , reflecting the range of potential paths. Analysis of deterministic models typically relies on exact analytical solutions or numerical methods like solving ordinary differential equations, allowing for precise predictions and sensitivity analysis without probabilistic considerations.[60] Stochastic models, however, require computational techniques to handle their probabilistic nature; common approaches include Monte Carlo simulations, which generate numerous random realizations to approximate outcomes, and calculations of expected values or variances to quantify average behavior and uncertainty.[64] For instance, in geometric Brownian motion, Monte Carlo methods simulate paths to estimate option prices or risk metrics by averaging over thousands of scenarios.[65] The choice between deterministic and stochastic models depends on the system's characteristics and data quality. Deterministic models are preferred for controlled environments with minimal variability, such as scheduled manufacturing processes or idealized physical systems, where predictability is high and exact solutions suffice.[42] Stochastic models are more appropriate for noisy or uncertain domains, like financial markets where random shocks influence prices, or biological systems with environmental fluctuations, enabling better representation of real-world variability through probabilistic forecasts.[66] In practice, stochastic approaches are employed when randomness significantly impacts outcomes, as in stock price modeling, to avoid underestimating risks that deterministic methods might ignore.[67]Other Types

Mathematical models can also be classified as explicit or implicit based on the form in which the relationships between variables are expressed. An explicit model directly specifies the dependent variable as a function of the independent variables, such as , allowing straightforward computation of outputs from inputs.[68] In contrast, an implicit model defines a relationship where the dependent variable is not isolated, requiring the solution of an equation like to determine values, often involving numerical methods for resolution.[68] This distinction affects the ease of analysis and simulation, with explicit forms preferred for simplicity in direct calculations.[69] Another classification distinguishes models by their construction approach: deductive, inductive, or floating. Deductive models are built top-down from established theoretical principles or axioms, deriving specific predictions through logical inference, as seen in physics-based simulations grounded in fundamental laws.[70] Inductive models, conversely, are developed bottom-up from empirical data, generalizing patterns observed in specific instances to form broader rules, commonly used in statistics and machine learning for hypothesis generation.[70] Floating models represent a hybrid or intermediate category, invoking structural assumptions without strict reliance on prior theory or extensive data, serving as exploratory frameworks for anticipated designs in early-stage modeling.[71] Models may further be categorized as strategic or non-strategic depending on whether they incorporate decision-making elements. Strategic models include variables representing choices or actions by agents, often analyzed through frameworks like game theory, where outcomes depend on interdependent strategies, as in economic competition scenarios. Non-strategic models, by comparison, are purely descriptive, focusing on observed phenomena without optimizing or selecting among alternatives, such as kinematic equations detailing motion paths.[72] This dichotomy highlights applications in optimization versus simulation. Hybrid models integrate elements from multiple classifications to address complex systems, such as semi-explicit formulations that combine direct solvability with stochastic components for uncertainty, or deductive-inductive approaches blending theory-driven structure with data-derived refinements.[73] These combinations enhance flexibility, allowing models to capture both deterministic patterns and probabilistic variations in fields like engineering and biology.[73]Construction Process

A Priori Information

A priori information in mathematical modeling encompasses the pre-existing knowledge utilized to initiate the construction process, serving as the foundational input for defining the system's representation. This information originates from diverse sources, including domain expertise accumulated through professional experience, scientific literature that synthesizes established theories, empirical observations from prior experiments, and fundamental physical laws such as conservation principles of mass, momentum, or energy. These sources enable modelers to establish initial constraints and boundaries, ensuring the model aligns with known physical or systemic behaviors from the outset. For example, conservation principles are routinely applied as a priori constraints in continuum modeling to derive phenomenological equations for fluid dynamics or heat transfer, directly informing the form of differential equations without relying on data fitting.[74][75] Subjective components of a priori information arise from expert judgments, which involve assumptions grounded in intuition, heuristics, or synthesized professional insights when empirical evidence is incomplete. These judgments allow modelers to prioritize certain mechanisms or relationships based on qualitative understanding, such as estimating relative importance in ill-defined scenarios. In contexts like regression modeling, fuzzy a priori information—derived from the designer's subjective notions—helps incorporate uncertain expert opinions to refine parameter evaluations under ambiguity. Such subjective inputs are particularly valuable in early-stage scoping, where they bridge gaps in objective data while drawing from observable patterns in related systems.[76][77] Objective a priori data provides quantifiable foundations through measurements, historical datasets, and theoretical analyses, playing a key role in identifying and initializing variables and parameters. Historical datasets, for instance, offer baseline trends that suggest relevant state variables, while prior measurements constrain possible parameter ranges to realistic values. In analytical chemistry modeling, technical details from instrumentation—such as spectral ranges in near-infrared spectroscopy—serve as objective priors to select variables, excluding unreliable intervals like 1000–1600 nm to focus on informative signals. This data-driven input ensures the model reflects verifiable system characteristics, enhancing its reliability from the initial formulation.[78] Integrating a priori information effectively delineates the model's scope by incorporating essential elements while mitigating risks of under-specification (omitting critical dynamics) or over-specification (including extraneous details). Domain expertise and physical laws guide the selection of core variables, populating the model's structural framework to align with systemic realities, whereas objective data refines these choices for precision. This balanced incorporation fosters models that are both interpretable and grounded, as seen in constrained optimization approaches where priors resolve underdetermined problems via methods like Lagrange multipliers for equality constraints. By leveraging these sources, modelers avoid arbitrary assumptions, promoting consistency with broader scientific understanding.[75][79]Complexity Management

Mathematical models often encounter complexity arising from high-dimensional parameter spaces, nonlinear dynamics, and multifaceted interactions among variables. High dimensions exacerbate the curse of dimensionality, a phenomenon where the volume of the space grows exponentially with added dimensions, leading to sparse data distribution, increased computational costs, and challenges in optimization or inference. Nonlinearities complicate analytical solutions and numerical stability, as small changes in inputs can produce disproportionately large output variations due to feedback loops or bifurcations.[80] Variable interactions further amplify this by generating emergent properties that defy simple summation, particularly in systems like ecosystems or economic networks where components influence each other recursively. Modelers address these issues through targeted simplification techniques that preserve core behaviors while reducing structural demands. Lumping variables aggregates similar states or species into representative groups, effectively lowering the model's order; for instance, in chemical kinetics, multiple reacting species can be combined into pseudo-components to facilitate simulation without losing qualitative accuracy. Approximations via perturbation methods exploit small parameters to expand solutions as series around a solvable base case, enabling tractable analysis of near-equilibrium systems like fluid flows under weak forcing. Modularization decomposes the overall system into interconnected but separable subunits, allowing parallel computation and easier debugging, as seen in simulations of large-scale engineering processes where subsystems represent distinct physical components. Balancing model fidelity with usability requires navigating inherent trade-offs. Simplifications risk underfitting by omitting critical details, resulting in predictions that fail to generalize beyond idealized scenarios, whereas retaining full complexity invites overfitting to noise or renders the model computationally prohibitive, especially for real-time applications or large datasets.[81] Nonlinear models, for example, typically demand more intensive management than linear counterparts due to their sensitivity to initial conditions. Effective complexity control thus prioritizes parsimony, ensuring the model captures dominant mechanisms without unnecessary elaboration. Key tools aid in pruning and validation during this process. Dimensional analysis, formalized by the Buckingham π theorem, identifies dimensionless combinations of variables to collapse the parameter space and reveal scaling laws, thereby eliminating redundant dimensions. Sensitivity analysis quantifies how output variations respond to input perturbations, highlighting influential factors for targeted reduction; global variants, such as Sobol indices, provide comprehensive rankings to discard negligible elements without compromising robustness. These approaches collectively enable scalable, interpretable models suited to practical constraints.Parameter Estimation

Parameter estimation involves determining the values of a mathematical model's parameters that best align with observed data, often by minimizing a discrepancy measure between model predictions and measurements. This process is crucial for tailoring models to empirical evidence, enabling accurate predictions and simulations across various domains. Techniques vary depending on the model's structure, with linear models typically employing direct analytical solutions or iterative methods, while nonlinear and stochastic models require optimization algorithms.[82] For linear models, the least squares method is a foundational technique, seeking to minimize the squared residuals between observed data and model predictions , where is the design matrix and the parameter vector. This is formulated as: The solution is given by under full rank conditions, providing an unbiased estimator with minimum variance for Gaussian errors. Developed by Carl Friedrich Gauss in the early 19th century, this method revolutionized data fitting in astronomy and beyond. In stochastic models, where parameters govern probability distributions, maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) maximizes the likelihood function , or equivalently its logarithm, to find parameters that make the observed data most probable. For independent observations, this often reduces to minimizing the negative log-likelihood. Introduced by Ronald A. Fisher in 1922, MLE offers asymptotically efficient estimators under regularity conditions and is widely used in probabilistic modeling. For nonlinear models, where analytical solutions are unavailable, gradient descent iteratively updates parameters by moving in the direction opposite to the gradient of the objective function, such as least squares residuals or negative log-likelihood. The update rule is , where is the learning rate and the cost function; variants like stochastic gradient descent use mini-batches for efficiency. This approach, rooted in optimization theory, enables fitting complex models but requires careful tuning to converge to global minima.[83] Training refers to fitting parameters directly to the entire dataset to minimize the primary objective, yielding point estimates for model use. In contrast, tuning adjusts hyperparameters—such as regularization strength or learning rates—using subsets of data via cross-validation, where the dataset is partitioned into folds, with models trained on all but one fold and evaluated on the held-out portion to estimate generalization performance. This distinction ensures hyperparameters are selected to optimize out-of-sample accuracy without biasing the primary parameter estimates.[84] To prevent overfitting, where models capture noise rather than underlying patterns, regularization techniques penalize large parameter values during estimation. L2 regularization, or ridge regression, adds a term to the objective, shrinking coefficients toward zero while retaining all features; pioneered by Andrey Tikhonov in the 1940s for ill-posed problems. L1 regularization, or Lasso, uses , promoting sparsity by driving some parameters exactly to zero, as introduced by Robert Tibshirani in 1996. Bayesian approaches incorporate priors on parameters, such as Gaussian distributions for L2-like shrinkage, updating them with data via Bayes' theorem to yield posterior distributions that naturally regularize through prior beliefs. A priori information can serve as initial guesses to accelerate convergence in iterative methods.[85] Numerical solvers facilitate these techniques in practice. MATLAB's Optimization Toolbox provides functions likelsqnonlin for nonlinear least squares and fminunc for unconstrained optimization, supporting gradient-based methods for parameter fitting. Similarly, Python's SciPy library offers optimize.least_squares for robust nonlinear fitting and optimize.minimize for maximum likelihood via methods like BFGS or L-BFGS-B, enabling efficient computation without custom implementations.

![{\displaystyle -{\frac {\mathrm {d} ^{2}\mathbf {r} (t)}{\mathrm {d} t^{2}}}m={\frac {\partial V[\mathbf {r} (t)]}{\partial x}}\mathbf {\hat {x}} +{\frac {\partial V[\mathbf {r} (t)]}{\partial y}}\mathbf {\hat {y}} +{\frac {\partial V[\mathbf {r} (t)]}{\partial z}}\mathbf {\hat {z}} ,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fd8f22ac8b8b4f56b4f541adcd524f759b5ed380)

![{\displaystyle m{\frac {\mathrm {d} ^{2}\mathbf {r} (t)}{\mathrm {d} t^{2}}}=-\nabla V[\mathbf {r} (t)].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fc987d59f3eb6aea08a9def1a21e4441af4456ea)