Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

United Nations Security Council Resolution 598

View on Wikipedia

| UN Security Council Resolution 598 | ||

|---|---|---|

Iran–Iraq War | ||

| Date | 20 July 1987 | |

| Meeting no. | 2,750 | |

| Code | S/RES/598 (Document) | |

| Subject | Iran–Iraq | |

Voting summary |

| |

| Result | Adopted | |

| Security Council composition | ||

Permanent members | ||

Non-permanent members | ||

| ||

United Nations Security Council resolution 598 S/RES/0598 (1987), (UNSC resolution 598)[1] adopted unanimously on 20 July 1987,[2] after recalling Resolution 582 and 588, called for an immediate ceasefire between Iran and Iraq and the repatriation of prisoners of war, and for both sides to withdraw to the international border. The resolution requested Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar to dispatch a team of observers to monitor the ceasefire while a permanent settlement was reached to end the conflict.

Iraq quickly accepted the resolution, but Iran refused to accept its terms until nearly a year after its adoption. Famously, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini felt that accepting the resolution was "more deadly than drinking from a poisoned chalice". The resolution finally became effective on 8 August 1988, ending all combat operations between the two countries and the Iran–Iraq War.

Resolution and initial reactions

[edit]The Security Council had unanimously adopted resolutions against the Iran-Iraq War twice in 1986, in resolutions 582 and 588. However, neither resolution was implemented by the warring parties. Resolution 598 was drafted in the wake of a report compiled at the behest of the Secretary-General which found that Iraq had used chemical weapons against Iranian troops. Unlike the previous two resolutions, resolution 598 was adopted under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, meaning that non-compliance could result in economic or military intervention. On 20 July, the Security Council invited Ismat Kittani, representative of Iraq, to a discussion of the war as a non-voting member. Its resolution, passed after this discussion, reaffirmed resolution 582 and demanded an immediate ceasefire and requested UN supervision of said ceasefire among other provisions.[3]

Two days after the resolution was issued, Iraq accepted it, but Iran refused to. Then-President Ali Khamenei stated that the resolution was the result of pro-Iraqi American pressure on the Security Council, and Supreme Leader Khomeini declared that, as final victory in the war was imminent, accepting a ceasefire would be tantamount to treason.[4]

In September 1987, President Khamenei flew to New York to attend the General Assembly and deliver a speech. Prior to the speech, American President Ronald Reagan asked for an unambiguous answer on the resolution from Khamenei; should Khamenei's answer be negative, the United States had no choice but to implement sanctions against Iran. In his speech, delivered on September 21, Khamenei reiterated that Iran was opposed to a ceasefire, and intended to "punish" Iraq's aggression.[5]

Despite Iran's refusal to accept, the US Navy, the French Navy and the British Navy as well as other navies local to the Persian Gulf enforced the resolution at sea. In an interview on 4 October 1987 aboard the flagship of the US forces, USS La Salle, Rear Admiral Harold Bernsen said "Of course we talk with them (the other navies), and we cooperate, but we don't have a joint command, what I would call a combined or coordinated military operation."[6]

By the Second Battle of al-Faw in spring 1988, Iran began to worry about the tenability of the war.[7] IRGC Commander-in-Chief Mohsen Rezaee delivered a "shocking" assessment to Khomeini that Iran would only be able to recommence offensive operations after 1992. In his 2015 memoir, Akbar Rafsanjani recounted that, by early summer 1988, the sentiment in Tehran was that continuation of the war was "no longer expedient". Khomeini remained resistant, but on the 15th convened a meeting and announced his begrudging acceptance of peace citing the assessment of Iranian commanders that a victory within the next five years was impossible. Iran accepted in a 17 July letter to the secretary-general, and on the same night, the news was broadcast to the Iranian people.[8]

On July 19th, in a public pronouncement on the one-year anniversary of the 1987 Mecca massacre, Khomeini spoke of Iran's acceptance of the resolution. Khomeini's statement that he was "drinking the cup of poison" became one of his most memorable and enduring quotes: "Happy are those who have departed through martyrdom. Unhappy am I that I still survive.… Taking this decision is more deadly than drinking from a poisoned chalice. I submitted myself to Allah's will and took this drink for His satisfaction."[9] According to Rafsanjani's son, Khomeini desired to step down as supreme leader after his acceptance of the resolution; Rafsanjani attempted to sign the decision and thus take responsibility himself, but was rebuffed.[10] Khomeini nonetheless would remain Supreme Leader until his death on 3 June 1989.

Iran's withdrawal from Iraqi territory was chaotic and bungled. War-weary Iranian soldiers laid down their arms upon hearing the news (despite the fact that the resolution was yet to be implemented), allowing Iraqi and MEK forces to make late gains. On 24 July, Khomeini ordered the creation of a drumhead "special war tribunal" tasked with the execution of officers who were responsible for territorial and military losses. Negotiations began in New York on 26 July as fighting continued.

Implementation and aftermath

[edit]Resolution 598 became effective on 8 August 1988.[11] A date of ceasefire was set for 3 AM on 20 August. Iranian forces withdrew from Iraqi territory, and vice versa.[12] UN peacekeepers belonging to the UNIIMOG mission took the field, remaining on the Iran–Iraq border until 1991. Some Iraqi forces, however, remained on small parts of Iranian territory, they were only evacuated on the eve of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. This evacuation was the final restoration of the status quo ante bellum, according to the 1975 borders.[13]

In accordance with paragraph 6 of the resolution, a Belgian delegation was selected to ascertain responsibility for the conflict. In a report delivered on December 9, 1991 (following the UN-condemned invasion of Kuwait and the beginning of the Gulf War), the delegation identified Iraq as the aggressor.[14] Paragraph 7 of the resolution recognized the necessity of reconstruction and international monetary assistance dedicated to it. Iran understood the paragraph as mandating war reparations, however, neither an international fund dedicated to reconstruction nor outright war reparations ever materialized.[15] As peace talks stalled shortly after the ceasefire, Iran and Iraq remain in an official state of ceasefire and the war's end was never formalized by a treaty.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "UN Security Council Resolution 598, Iran / Iraq". Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Farrokh, Kaveh (20 December 2011). Iran at War: 1500–1588. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-221-4.

- ^ "Resolution 598 (1987) /: adopted by the Security Council at its 2750th meeting, on 20 July 1987". United Nations Digital Library. 20 July 1987.

- ^ "وقتی ایران اعلام کرد 'هرگز قطعنامه ۵۹۸ را قبول نخواهد کرد'". BBC News فارسی (in Persian). Retrieved 18 June 2025.

- ^ "وقتی ایران اعلام کرد 'هرگز قطعنامه ۵۹۸ را قبول نخواهد کرد'". BBC News فارسی (in Persian). Retrieved 17 June 2025.

- ^ "Rear Admiral Harold J. Bernsen, commander of the U.S.... - UPI Archives". 4 October 1987.

- ^ "انتشار خاطرات هاشمی رفسنجانی درباره تصمیم خمینی برای «کنارهگیری از رهبری» با پذیرش قطعنامه". BBC News فارسی (in Persian). Retrieved 17 June 2025.

- ^ "چرا آیت الله خمینی خواستار اعدام فرماندهان مقصر 'شکست' در جنگ شد؟". BBC News فارسی (in Persian). 23 September 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2025.

- ^ "جام زهر؛ پیام آیت الله خمینی به مناسبت پذیرش قطعنامه ۵۹۸". BBC News فارسی (in Persian). 20 September 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2025.

- ^ "انتشار خاطرات هاشمی رفسنجانی درباره تصمیم خمینی برای «کنارهگیری از رهبری» با پذیرش قطعنامه". BBC News فارسی (in Persian). Retrieved 18 June 2025.

- ^ "Strait of Hormuz – Tanker War". The Strauss Center. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ Dodds, Joanna; Wilson, Ben (6 June 2009). "The Iran–Iraq War: Unattainable Objectives". Middle East Review of International Affairs. 13 (2).

- ^ "The Iran-Iraq War: The Most Amateurish Ceasefire". iranwire.com. Retrieved 18 June 2025.

- ^ "معرفى عراق به عنوان متجاوز جنگ توسط سازمان ملل". دیپلماسی ایرانی (in Persian). Retrieved 17 June 2025.

- ^ "ناگفتههای خرازی از قطعنامه 598". دیپلماسی ایرانی (in Persian). Retrieved 18 June 2025.

- ^ "Adjusting implementation arrangements of Resolution 598 and the implementation of the 1975 Treaty". Tehran Times. 23 September 2024. Retrieved 18 June 2025.

External links

[edit]United Nations Security Council Resolution 598

View on GrokipediaHistorical Context

Origins of the Iran-Iraq War

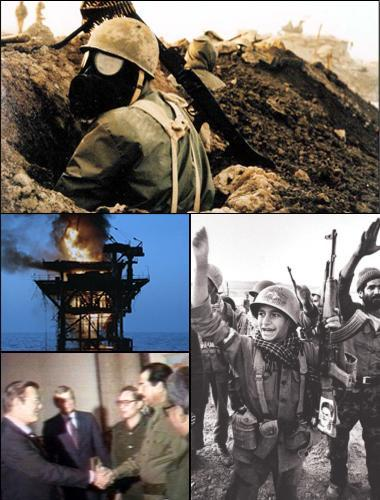

The origins of the Iran-Iraq War trace back to longstanding territorial disputes, particularly over the Shatt al-Arab waterway, which forms the border in the south and serves as Iraq's primary outlet to the Persian Gulf. Control of this vital shipping route had been contested since the 19th century, with Iraq historically claiming sovereignty based on Ottoman-Persian treaties, while Iran sought equal thalweg division. In 1975, the Algiers Agreement delimited the border along the deepest channel of the Shatt al-Arab, granting Iran navigational rights and access to half the waterway, in exchange for Iran ceasing support to Iraqi Kurdish rebels.[9][10] Iraq, under Saddam Hussein who was then vice president, viewed this concession as a humiliating capitulation to Iranian pressure amid its internal Kurdish insurgency.[11] The 1979 Iranian Revolution fundamentally altered the regional dynamics, overthrowing Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and establishing an Islamic Republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who advocated exporting Shia revolutionary ideology. Saddam Hussein, having consolidated power as Iraq's president in July 1979, feared this ideology would incite Iraq's Shia majority—comprising about 60% of the population—against his secular Ba'athist regime, especially given Iran's sponsorship of assassination attempts, bombings, and uprisings within Iraq targeting Ba'ath leaders.[12][13] Khomeini's rhetoric explicitly called for the overthrow of Saddam, framing him as an apostate, which heightened Iraqi perceptions of an existential threat from a theocratic neighbor.[14] Post-revolution purges decimated Iran's military officer corps, reducing its effectiveness by an estimated 50-70%, while the U.S. embassy hostage crisis isolated Tehran internationally, presenting Saddam with an opportunity to strike a weakened foe.[14] In the prelude to invasion, Iraq accused Iran of violating the Algiers Agreement through cross-border incursions and support for Iraqi dissidents, prompting Saddam to abrogate the treaty on September 17, 1980, and declare full Iraqi sovereignty over the Shatt al-Arab. Five days later, on September 22, 1980, Iraqi forces launched a full-scale invasion, beginning with airstrikes on 10 Iranian airfields and followed by ground assaults into Iran's oil-rich Khuzestan province, home to a significant Arab minority that Iraq claimed to "liberate" from Persian dominance.[14] Saddam's strategic aims included securing the entire Shatt al-Arab, annexing Khuzestan to bolster Iraq's oil production and access to Arabistan's resources, and preempting Iranian revolutionary subversion, calculating on a swift victory akin to the Six-Day War.[14] These motivations combined opportunistic expansionism with defensive fears, though Iraq's initiation of hostilities positioned it as the aggressor in the ensuing eight-year conflict.[15]Escalation and Prior UN Resolutions

The Iran-Iraq War began with Iraq's invasion of Iran on September 22, 1980, initially achieving territorial gains before Iranian counteroffensives from May 1982 reversed most advances, shifting the conflict into a protracted stalemate marked by high-casualty infantry assaults and defensive fortifications.[14] By 1983, Iraq escalated through the systematic use of chemical weapons, deploying mustard gas and tabun against Iranian forces to blunt human-wave attacks, with documented instances causing over 20,000 Iranian casualties by mid-decade.[16] The Tanker War intensified in 1984 as Iraq expanded airstrikes on Iranian oil tankers and facilities, prompting Iran to mine the Persian Gulf and target neutral shipping bound for Iraq's allies, resulting in approximately 546 attacks on merchant vessels between May 1984 and March 1987 and threatening global oil supplies.[17] Concurrently, both sides launched ballistic missile strikes on civilian population centers starting in 1985, known as the "War of the Cities," which killed hundreds and displaced thousands, further broadening the conflict's scope.[14] Prior United Nations Security Council efforts to halt the war proved ineffective, starting with Resolution 479, adopted unanimously on September 28, 1980, which urged both parties to cease further use of force and accept mediation offers.[18] Resolution 514, passed on July 12, 1982, demanded an immediate ceasefire and withdrawal to internationally recognized boundaries, but Iran rejected it, viewing Iraq as the unpunished aggressor and pressing its offensives into Iraqi territory.) Later resolutions, including 582 on February 24, 1986, which called for a ceasefire, prisoner exchanges, and condemned chemical weapon use without attributing responsibility, and 588 on October 8, 1986, reiterating these demands, similarly failed due to the absence of mandatory sanctions or enforcement mechanisms and Iran's insistence on preconditions like Saddam Hussein's trial.[19][20]| Resolution | Date Adopted | Key Elements |

|---|---|---|

| 479 | September 28, 1980 | Called for end to hostilities and mediation.[18] |

| 514 | July 12, 1982 | Demanded ceasefire and border withdrawal.) |

| 582 | February 24, 1986 | Urged ceasefire, POW repatriation, chemical weapons condemnation.[19] |

Provisions of the Resolution

Core Demands and Mechanisms

Resolution 598 demanded that Iran and Iraq immediately implement a ceasefire, discontinue all military actions on land, at sea, and in the air, and withdraw their forces to the internationally recognized boundaries without delay as the initial step toward a negotiated settlement. This demand was framed under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, determining that a breach of the peace existed due to the prolonged conflict, which had caused heavy loss of human and material resources since September 1980.[21] The resolution further urged the prompt release and repatriation of all prisoners of war in accordance with the Third Geneva Convention of 1949, emphasizing the humanitarian imperative amid reports of over 500,000 prisoners held by both sides by mid-1987.[5] To enforce these demands, the resolution requested the Secretary-General to dispatch a team of United Nations observers to the region to verify, confirm, and supervise the ceasefire and troop withdrawals, with a mandate to report findings to the Security Council expeditiously. It also called upon both parties to cooperate fully with the Secretary-General in mediation efforts aimed at a comprehensive political settlement based on respect for sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity, while requesting the exploration of an impartial mechanism—potentially an independent body—to investigate responsibility for initiating the conflict and its prolongation.[21] Additional mechanisms included appeals to all states to exercise restraint and avoid actions that could escalate the conflict, such as arms supplies or interference, and a directive for the Secretary-General to assess needs for reconstruction, repatriation of refugees, and economic development in the war-affected regions.[5] The resolution's enforcement provisions lacked explicit coercive measures like sanctions or military authorization at adoption, relying instead on diplomatic pressure and voluntary compliance, though it invoked Articles 39 and 40 of the UN Charter to underscore the Council's authority to maintain international peace. This approach reflected the Council's prior unsuccessful resolutions (e.g., 582 in 1986), which had similarly urged ceasefires without binding enforcement, highlighting a pattern of escalating rhetorical demands amid non-compliance by Iran.[21] Subsequent reporting by the Secretary-General was to include progress on these mechanisms, paving the way for observer deployment under what became the United Nations Iran-Iraq Military Observer Group (UNIIMOG) in 1988.[5]Legal Framework and Enforcement

United Nations Security Council Resolution 598 was adopted on 20 July 1987 under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, acting specifically under Articles 39 and 40, after determining the existence of a breach of the peace arising from the Iran-Iraq conflict.[21] This determination elevated the resolution beyond the recommendatory nature of earlier Chapter VI measures, imposing binding obligations on all UN member states, including Iran and Iraq, to comply pursuant to Article 25 of the Charter, which requires members to accept and carry out Security Council decisions.[22] The resolution's demands for an immediate ceasefire, troop withdrawal to internationally recognized boundaries, repatriation of prisoners of war without reciprocity, and cooperation in post-withdrawal arrangements thus carried legal force, though attribution of aggression responsibility (as explored in paragraph 10 via an impartial inquiry) remained deferred and politically contentious.[23] Enforcement mechanisms centered on supervisory observation rather than immediate coercive sanctions or military action. Paragraph 2 requested the Secretary-General to dispatch a team of observers to monitor the ceasefire, providing the initial framework for verification that evolved into the United Nations Iran-Iraq Military Observer Group (UNIIMOG) through subsequent resolutions.[23] Resolution 619, adopted on 9 August 1988 under Chapter VII, formally established UNIIMOG with a mandate to verify and supervise the ceasefire, confirm withdrawals, and oversee related activities, deploying 344 military observers from 35 countries by late 1988.[3] This observer mission operated from bases along the 1,400-kilometer border, conducting patrols and inspections to ensure compliance, and completed its core tasks by February 1991 after verifying full withdrawals.[3] The resolution implicitly threatened escalation by declaring the Council's intent to remain seized of the matter and consider further steps for non-compliance, but practical enforcement hinged on diplomatic pressure and parties' voluntary adherence amid battlefield dynamics. Iraq's prompt acceptance enabled partial implementation, including observer dispatches, but Iran's rejection until 18 July 1988—following Iraqi territorial gains—delayed activation until 20 August 1988, underscoring the limits of legal bindingness without unified enforcement will among permanent Council members or additional measures like those later invoked in other conflicts.[21] UNIIMOG's success in monitoring the 1988 ceasefire and withdrawals, despite occasional violations such as sporadic artillery exchanges, demonstrated the efficacy of neutral verification in sustaining fragile compliance, though the mission's termination in 1991 reflected resolution of immediate enforcement needs rather than comprehensive conflict settlement.[3]Adoption Process

Negotiations and Voting

The negotiations preceding the adoption of Resolution 598 involved intensive consultations among Security Council members, prompted by the protracted Iran-Iraq War and reports of escalating chemical weapon use by Iraqi forces against Iranian troops. These discussions built on prior UN efforts, including Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar's initiatives to mediate peace, and addressed the limitations of earlier advisory resolutions that had failed to halt hostilities. The process culminated in a draft resolution (S/18983) that imposed binding demands under the Council's authority, marking a shift toward enforceable measures amid international frustration with the conflict's prolongation.[2][23] At the Council's 2750th meeting on July 20, 1987, the representative of Iraq was invited to participate without voting rights to discuss the item, reflecting procedural norms for non-members directly affected. The draft was then put to a vote among the 15 Council members—comprising the five permanent members (China, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States) and ten elected members (Argentina, Bulgaria, People's Republic of the Congo, Federal Republic of Germany, Ghana, Italy, Japan, United Arab Emirates, and Zambia)—and adopted unanimously with no abstentions or negative votes. This consensus underscored rare unity among the permanent members, including ideological rivals like the United States and Soviet Union, driven by shared concerns over regional instability and humanitarian costs.[2][23][24] The unanimous adoption highlighted the resolution's framing as a "first step towards a negotiated settlement," demanding an immediate ceasefire, troop withdrawals to internationally recognized boundaries, and cooperation with the Secretary-General for implementation, including an investigation into war responsibility. While the negotiations prioritized enforceability over assigning blame at the outset—despite evidence of Iraqi initiation of hostilities—the process avoided vetoes by balancing demands on both parties, facilitating passage despite subsequent rejections by Iran.[23][2]Immediate Responses

Iraq's Acceptance

Iraq formally accepted United Nations Security Council Resolution 598 immediately following its unanimous adoption on 20 July 1987. Iraqi officials, including Foreign Minister Tariq Aziz, hailed the resolution as a diplomatic success, emphasizing its call for an immediate ceasefire, troop withdrawals to internationally recognized borders, and an impartial investigation into the war's origins without initially assigning blame.[25] This stance aligned with Iraq's strategic position at the time, as its military had regained most pre-war territory and mounted successful offensives, positioning the resolution as a means to freeze gains and compel Iran's compliance amid ongoing Iranian rejection.[4] Saddam Hussein's government viewed the resolution's provisions—demanding cessation of hostilities, POW exchanges, and border verification—as favorable, interpreting the lack of explicit condemnation of Iraq as the 1980 invader as implicit validation of its defensive posture after Iran's counteroffensives. Iraqi state media and spokespersons reiterated commitment to full implementation once Iran reciprocated, while Baghdad continued air and ground operations to maintain pressure, arguing that unilateral restraint would reward Tehran's intransigence.[26] This acceptance was unconditional in public statements, contrasting with Iran's demands for preconditions like Saddam's removal and reparations, which Iraq dismissed as obstructive.[4] Despite the endorsement, Iraq's adherence hinged on reciprocity, leading to no immediate de-escalation; Baghdad notified the UN Secretary-General of its readiness to observe the ceasefire terms, including dispatching observers, but proceeded with strikes such as the 29 July 1987 attack on the USS Stark, which it framed as unrelated to the resolution's framework.[25] Over the ensuing months, Iraq lobbied internationally for enforcement mechanisms against Iran, reinforcing its acceptance through diplomatic channels while sustaining military momentum until Iran's eventual capitulation in July 1988.[27]Iran's Initial Rejection

Iran rejected United Nations Security Council Resolution 598 immediately following its unanimous adoption on July 20, 1987, with officials in Tehran describing the measure as unacceptable for failing to explicitly identify Iraq as the aggressor who initiated hostilities on September 22, 1980.[28][26] The Iranian position emphasized that the resolution's sequence—demanding an immediate ceasefire and troop withdrawals to internationally recognized borders before any investigation into war responsibility—unfairly equated the invaded party with the invader, thereby shielding Iraq from accountability for its invasion and subsequent use of prohibited weapons, including chemical agents against Iranian forces and civilians.[6][4] Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his inner circle viewed compliance as tantamount to capitulation, insisting instead on preconditions such as a prior UN determination of aggression, Iraqi reparations for damages estimated by Iran at over $600 billion, and guarantees against future Iraqi incursions.[6][4] Foreign Ministry spokespersons articulated this stance publicly, arguing that the resolution's impartial framing ignored documented evidence of Iraqi initiation, including the unprovoked cross-border attacks that prompted Iran's defensive response and the conflict's prolongation through Iraqi escalations like the 1984 tanker war.[26] This rejection persisted despite diplomatic overtures from UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, who urged Iran to reconsider amid mounting casualties—over 200,000 Iranian deaths by mid-1987—and economic strain from the war's drain on resources. Internally, while some pragmatic elements within the Iranian leadership acknowledged the resolution's potential as a framework for negotiation if amended, hardline factions dominated, prioritizing ideological resolve over immediate peace and framing acceptance as a betrayal of the Islamic Revolution's principles.[6] Iran's non-compliance extended to continued military offensives, such as operations in Iraqi Kurdistan, underscoring the government's commitment to forcing a decisive victory rather than endorsing a truce perceived as rewarding aggression.[4] This stance drew criticism from permanent Security Council members, who saw it as prolonging unnecessary suffering, though Iranian diplomats countered that Western support for Iraq—evidenced by arms sales and intelligence sharing—had biased the UN process against Tehran's claims.[6]Path to Ceasefire

Factors Leading to Iranian Acceptance

Iran's acceptance of Resolution 598 on July 18, 1988, followed a series of decisive Iraqi military successes earlier that year, which reversed Iranian gains and inflicted severe losses. In April 1988, Iraqi forces recaptured the Faw Peninsula—a strategically vital territory seized by Iran in 1986—during Operation Tawakalna ala Allah, marking a humiliating defeat that exposed Iran's logistical and manpower vulnerabilities. Subsequent offensives reclaimed the Majnoon Islands and other border areas, with Iraqi chemical weapon attacks contributing to an estimated 50,000 Iranian casualties in 1988 alone, eroding Iran's offensive capacity and forcing a defensive posture.[4][29] Compounding these battlefield reversals was profound economic exhaustion from eight years of total war, which had depleted Iran's oil revenues through disrupted exports and imposed sanctions, leading to hyperinflation exceeding 50% annually by 1988 and widespread shortages of food and fuel. The war's fiscal toll, estimated at over $500 billion in combined damages, strained Iran's ability to sustain mobilization, with industrial output halved and agricultural production crippled, prompting internal debates on the sustainability of continued conflict.[4][30] Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Iran's supreme leader, ultimately endorsed acceptance despite viewing it as akin to "drinking poison," prioritizing the regime's survival over ideological goals like regime change in Iraq or immediate reparations. In a July 1988 message, Khomeini argued the decision safeguarded Islamic interests and prevented further devastation to the revolution, reflecting a pragmatic assessment that prolonged fighting risked collapse amid mounting defeats and isolation, including U.S. naval engagements in the Gulf. This shift aligned with advice from military commanders and pragmatists like Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who later noted the resolution was accepted under optimal remaining conditions to avert total ruin.[31]Ceasefire Activation and UNIIMOG Deployment

Iran formally notified United Nations Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar of its acceptance of Resolution 598 on 17 July 1988, prompting Iraq to reaffirm its prior acceptance the following day.[3] This paved the way for activation of the ceasefire provisions, with Pérez de Cuéllar designating 20 August 1988 at 0300 GMT as the effective date for the cessation of hostilities.[3] The ceasefire marked the end of active combat in the eight-year Iran-Iraq War, though isolated violations occurred in the immediate aftermath as forces disengaged from contested positions.[3] To oversee implementation, the Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 619 on 9 August 1988, establishing the United Nations Iran-Iraq Military Observer Group (UNIIMOG) under Chapter VI of the UN Charter for an initial six-month period.[32] UNIIMOG's mandate focused on verifying, confirming, and supervising the ceasefire, the withdrawal of all forces to internationally recognized boundaries, and related measures outlined in Resolution 598, including the repatriation of prisoners of war.[3] The mission operated without enforcement powers, relying on unarmed military observers to monitor compliance through patrols and liaison with both parties' forces.[3] Deployment commenced rapidly, with advance parties of 12 military observers, team leaders, and civilian staff arriving in Iran and Iraq on 10 August 1988 to establish forward observation teams along the 1,400-kilometer border.[33] By the ceasefire's activation on 20 August, UNIIMOG had positioned approximately 350 military observers from 34 countries, including Argentina, Australia, Canada, India, and Sweden, divided into teams in both nations with headquarters in Tehran and Baghdad.[3] Initial operations faced logistical hurdles, such as disagreements over access to forward defended localities and restrictions on UN helicopter use by one party, which limited aerial observation capabilities.[3] Despite these, the observers reported broad adherence to the ceasefire line, facilitating the phased withdrawal process.[3]Implementation Challenges

Troop Withdrawals and Border Demarcation

The United Nations Iran-Iraq Military Observer Group (UNIIMOG), established by Security Council Resolution 619 on August 9, 1988, deployed approximately 344 military observers from 35 countries to verify, confirm, and supervise the ceasefire and troop withdrawals to the internationally recognized boundaries as required by Resolution 598.[3] UNIIMOG divided the 1,452-kilometer border into 14 operational sectors and established teams to monitor redeployments, investigate alleged violations, and facilitate local joint commissions between Iranian and Iraqi military commanders for dispute resolution.[3] The mission's terms of reference emphasized phased withdrawals without prejudice to subsequent border negotiations, with observers positioned at key checkpoints and forward areas to ensure compliance.[34] Troop redeployments proceeded unevenly amid mutual accusations of delay and minor incursions, particularly in contested sectors near the Shatt al-Arab waterway and the Faw Peninsula, where Iraq held advances into Iranian territory at the ceasefire's onset on August 20, 1988.[29] UNIIMOG reported progressive withdrawals, with Iraq vacating occupied Iranian positions and Iran pulling back from limited Iraqi enclaves, though verification was complicated by minefields, destroyed infrastructure, and occasional artillery exchanges that the group investigated and mediated.[3] By late 1989, the mission confirmed substantial completion of redeployments across most sectors, enabling UNIIMOG to shift focus toward ceasefire stabilization ahead of its mandate extensions.[35] Border demarcation proved contentious, as Resolution 598 mandated adherence to "internationally recognized boundaries" without specifying a mechanism, leaving ambiguities rooted in prior treaties like the 1975 Algiers Agreement, which allocated the Shatt al-Arab thalweg (deepest channel) line to Iran—a concession Iraq had repudiated in 1980 to justify its invasion.[10] Iran insisted on full restoration of these lines, including equal navigational rights in the waterway, while Iraq sought revisions favoring its sovereignty claims; UNIIMOG's supervisory role did not extend to binding demarcation, deferring it to bilateral talks under UN auspices that yielded protocols affirming pre-war boundaries by 1990.[29] Delays persisted due to these disputes and logistical hurdles, with formal demarcation surveys not fully advancing until after UNIIMOG's termination on February 28, 1991, following verified withdrawal compliance.[34] The process underscored the resolution's emphasis on status quo ante boundaries, though isolated violations and unresolved claims highlighted enforcement limitations absent Chapter VII measures.[2]Prisoner of War Repatriation

The implementation of prisoner of war (POW) repatriation under Resolution 598 encountered substantial obstacles, despite the resolution's explicit urging for the release and repatriation of all POWs without delay following the cessation of active hostilities, in accordance with the Third Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War.[21] The ceasefire's activation on August 20, 1988, marked the formal starting point, but Iran and Iraq diverged sharply on procedures: Iran insisted on a comprehensive, simultaneous "all-for-all" exchange to ensure reciprocity, while Iraq favored a phased repatriation categorized by capture date, rank, or other criteria, leading to mutual suspensions of transfers and accusations of non-compliance.[36] The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), designated as the neutral intermediary, played a central role in registering detainees, verifying identities, and organizing convoys, as UNIIMOG's mandate focused primarily on military withdrawals rather than POW logistics.[37] Initial small-scale exchanges occurred sporadically in late 1988, but systematic repatriations commenced only in March 1989 after Iran accepted an ICRC-proposed phased plan, with Iraq following suit; over the next 14 months, 11 operations facilitated the return of approximately 70,000 POWs, including around 42,000 Iraqis from Iran and 28,000 Iranians from Iraq.[37] These efforts involved ICRC delegates escorting groups across border points like Khanaqin and Qasr-e Shirin, often under tight security amid lingering hostilities. Persistent challenges included discrepancies in reported detainee numbers—Iran claimed Iraq held up to 20,000 more Iranian POWs than admitted, while Iraq alleged Iran withheld thousands of its own—and issues with unvisited or "missing" prisoners whom the ICRC could not access during the war, complicating verification.[37] Both parties periodically halted exchanges, citing violations such as alleged forced confessions or battlefield recoveries misclassified as POWs, which prolonged the process beyond the resolution's envisioned timeline.[36] Although the bulk of repatriations concluded by mid-1990, residual cases, including those involving trials for war crimes or unresolved fates, extended into the 1990s and early 2000s, underscoring the resolution's limitations in enforcing humanitarian obligations without robust verification mechanisms.[37]War Responsibility Investigation

Establishment of the Inquiry

Paragraph 10 of United Nations Security Council Resolution 598, adopted unanimously on 20 July 1987, requested the Secretary-General to explore, in consultation with Iran and Iraq, the question of entrusting an impartial body with inquiring into responsibility for the conflict and to report to the Security Council as soon as possible.) This mandate sought to address the origins of the war, which Iraq had initiated through its invasion of Iran on 22 September 1980.) The provision reflected international consensus on the need for an objective determination of aggression, amid prior resolutions that had condemned Iraq's actions but stopped short of explicit attribution due to geopolitical divisions.) Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar undertook initial consultations with representatives of both belligerents to gauge feasibility and composition of the proposed impartial body, emphasizing neutrality and access to evidence from the war's outset. These efforts, however, encountered immediate resistance: Iraq viewed its acceptance of Resolution 598 as sufficient closure on origins, while Iran insisted on formal designation of Iraq as the aggressor prior to full implementation of other resolution elements.[38] No dedicated inquiry mechanism was operationalized by 1991, as Security Council follow-up reports noted the absence of agreed mechanisms despite the mandate's intent for prompt action. The inquiry's framework prioritized empirical review of military actions, diplomatic records, and witness accounts, but lacked enforcement powers, rendering it advisory rather than binding. This limited scope, combined with veto-holding members' reluctance to alienate Iraq—a key counterweight to Iran—undermined establishment of a robust body, as evidenced by stalled consultations documented in subsequent Secretary-General updates to the Council.Disputes and Unresolved Outcomes

The mandate under paragraph 8 of Resolution 598 for an impartial body to inquire into responsibility for the Iran-Iraq conflict encountered immediate contention over its scope and preconditions. Iran demanded that the inquiry prioritize identifying Iraq as the aggressor—citing its unprovoked invasion on September 22, 1980, which involved airstrikes on ten Iranian airfields and ground incursions across a 644-kilometer front—before proceeding to reparations or normalization, arguing this was essential for equitable post-war accountability. Iraq countered that such determinations risked politicization and should follow troop withdrawals, POW exchanges, and border demarcation to avoid prejudging outcomes amid ongoing hostilities. Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar initiated consultations as required, reporting in October 1988 and subsequent updates that both parties diverged sharply on the body's composition—proposing neutral experts versus balanced representation—and terms of reference, with Iran seeking explicit linkage to aggression attribution and Iraq favoring a narrower focus on conflict origins without assigning culpability.[23] These impasse persisted through 1989, exacerbated by Iraq's reluctance to concede liability amid its military setbacks and Iran's insistence on historical grievances, including Iraq's prior territorial claims on Khuzestan and Shatt al-Arab waterway disputes. No agreement emerged, and the Security Council deferred action, prioritizing UNIIMOG verification over enforcement of the inquiry provision.[39] Consequently, the impartial body was never established, leaving war responsibility undetermined within Resolution 598's framework and forestalling any reparations mechanism tied to aggression findings. While Pérez de Cuéllar referenced Iraq's initiatory role in informal assessments and later UN contexts post-1990 Gulf crisis implicitly acknowledged it through resolutions condemning Iraq's pattern of invasions, no formal adjudication occurred, perpetuating bilateral recriminations without resolution.[40] This omission contributed to protracted claims processes outside UN auspices, with Iran pursuing bilateral compensation claims totaling over $1 trillion in damages, unaddressed by the Council.[41]Controversies and Criticisms

Iranian Claims of Bias

Iran maintained that United Nations Security Council Resolution 598 demonstrated institutional bias by imposing symmetrical obligations on both belligerents without explicitly condemning Iraq's initiation of hostilities on September 22, 1980, thereby equating the invaded party with the invader.[42] Iranian officials argued that this equal treatment overlooked documented Iraqi aggression, including the invasion of sovereign Iranian territory and subsequent territorial seizures, which the resolution neither reversed nor penalized prior to demanding a ceasefire.[42][43] Tehran criticized the resolution's provision for an "impartial body" to investigate war responsibility—outlined in operative paragraph 6—as insufficiently guaranteed against influence from permanent Security Council members who had materially supported Iraq, such as arms supplies from the Soviet Union and financial aid from Western-aligned Gulf states.[2][44] Iran asserted that the Council's reluctance to preemptively attribute blame reflected a pro-Iraq tilt, evidenced by prior resolutions' muted responses to Iraq's chemical weapon deployments against Iranian forces, confirmed in UN investigations as early as March 1984.[2][44] This perception was compounded by Iran's initial rejection of the resolution upon its adoption on July 20, 1987, citing "fundamental defects and incongruities" that favored the party backed by major powers.[3] Iranian leadership, including Foreign Ministry spokespersons, contended that the resolution's structure rewarded Iraq's intransigence by permitting it to retain occupied territories pending negotiations, without mechanisms to enforce Iraq's withdrawal to pre-war borders as stipulated under international law.[42][43] Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini later described acceptance on July 17, 1988, as akin to "drinking poison," underscoring Iran's view that the terms were coerced amid military setbacks rather than reflecting equitable adjudication.[45] Despite these objections, Iran conditioned its compliance on the impartial body's activation, though subsequent disputes over its composition and findings perpetuated accusations of UN partiality influenced by geopolitical alignments favoring Iraq.[42][43]Assessments of UN Impartiality

Iran repeatedly accused the United Nations of partiality in implementing Resolution 598, primarily because the text deferred assigning responsibility for initiating the war to an "impartial body" rather than immediately designating Iraq as the aggressor following its invasion on September 22, 1980.[42] Iranian officials argued that this neutrality ignored established facts of Iraqi aggression, including the initial cross-border incursion and subsequent use of chemical weapons, thereby favoring Iraq diplomatically.[42] Such claims were rooted in Iran's precondition for ceasefire acceptance: explicit condemnation of Iraq, which the Security Council avoided to secure broad support amid divided permanent member interests, with the United States and Soviet Union prioritizing war termination over retrospective blame.[46] Defenders of the UN's approach, including Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, maintained that Resolution 598's balanced language—demanding mutual withdrawal to internationally recognized boundaries without preconditions—facilitated the eventual ceasefire on August 20, 1988, by accommodating both parties' positions and averting vetoes in the Council.[2] The resolution's call for an impartial inquiry into war origins, though unimplemented during active hostilities, aligned with Chapter VII procedures under the UN Charter, emphasizing de-escalation over punitive measures that could prolong conflict.[2] However, this deferral fueled perceptions of bias, as Western-leaning members reportedly influenced the Council's reluctance to single out Iraq early, despite UN specialists' confirmations of Iraqi chemical weapon use by 1984.[2] In a 1991 report (S/22559), Pérez de Cuéllar concluded that Iraq bore primary responsibility for starting the war, validating Iran's long-standing position but arriving years after the ceasefire and without enforcing reparations under the resolution.[47] This post-hoc assessment underscored criticisms that the UN prioritized geopolitical pragmatism—bolstered by Iraq's alignment with anti-Iran coalitions—over consistent application of international law, as evidenced by the Council's slower response to Iraq's aggression compared to later condemnations post-1990 Kuwait invasion.[44] Iranian analysts have since cited this as systemic partiality, arguing that Security Council dynamics, including veto powers held by Iraq's tacit supporters, undermined the body's credibility in mediating equitably.[48] Independent evaluations, such as declassified U.S. intelligence summaries, note that while the resolution achieved tactical impartiality in observer deployment via UNIIMOG, its avoidance of blame attribution reflected member states' strategic calculations rather than pure evidentiary neutrality.[42]Strategic Motivations of Key Actors

The United States pursued Resolution 598 to safeguard Persian Gulf shipping lanes critical for global oil transit, amid escalating Iranian attacks on neutral vessels in the "Tanker War" that prompted U.S. naval escorts under Operation Earnest Will starting in mid-1987.[49] U.S. policymakers viewed the ceasefire as a means to neutralize Iran's asymmetric threats, including mining and speedboat assaults, while leveraging Iraq's battlefield momentum to compel Tehran toward negotiations without conceding to revolutionary expansionism.[50] This aligned with broader strategic containment of Iran following the 1979 hostage crisis and hostage-taking incidents, prioritizing stability over prolonged attrition that risked wider regional spillover.[22] The Soviet Union, under Mikhail Gorbachev's "new thinking" in foreign policy, backed the resolution to foster détente with the West and mitigate the war's drain on Soviet resources, having supplied arms to both sides but halting exports in 1987 to incentivize de-escalation.[50] Moscow aimed to preserve influence in the Middle East without alienating Arab allies like Iraq, while avoiding entanglement in a conflict paralleling its Afghan quagmire; the unanimous vote marked rare P5 unity, reflecting Gorbachev's emphasis on multilateralism to reduce global tensions.[51] France and the United Kingdom supported the measure to secure economic stakes tied to Iraq, including French arms sales exceeding $5 billion and loans repayable via oil, positioning the ceasefire to consolidate Iraq's defensive gains against Iranian incursions.[52] Both nations sought to avert further disruption to energy markets, with the UK emphasizing resolution of shipping attacks as a core driver for addressing conflict roots.[52] China's endorsement stemmed from pragmatic interests in regional stability to safeguard burgeoning trade and arms exports to both combatants, viewing the war's prolongation as antithetical to economic modernization goals post-Deng Xiaoping reforms.[25]Long-Term Impact

Effects on Iran-Iraq Relations

The acceptance of Resolution 598 by Iran on July 18, 1988, and Iraq shortly thereafter resulted in an immediate ceasefire on August 20, 1988, enforced by the United Nations Iran-Iraq Military Observer Group (UNIIMOG), which verified the withdrawal of forces to international borders by early 1989.[3] This halted direct hostilities after eight years of conflict that caused an estimated 500,000 to 1 million deaths and widespread destruction, preventing further escalation but leaving core disputes unresolved, including border demarcations and reparations.[53] Prisoner exchanges proceeded slowly, with over 100,000 POWs repatriated by the mid-1990s under UN auspices, though full compliance lagged due to mutual accusations of withholding captives.[53] Diplomatic relations, severed since the war's outset in 1980, remained frozen in the immediate post-ceasefire period, with both regimes viewing the other as an existential threat—Iraq under Saddam Hussein portraying Iran as an aggressor to justify its invasion, while Iran demanded acknowledgment of Iraq's responsibility for initiating the conflict.[54] No formal peace treaty materialized despite Resolution 598's call for negotiations, resulting in a technical state of neither war nor peace that persisted into the 21st century, as outstanding issues like war guilt investigations stalled without conclusion.[2] Iraq's failure to pay substantial reparations—limited to partial UN disbursements from frozen Iraqi oil revenues—fueled Iranian grievances, exacerbating bilateral distrust.[53] A partial thaw occurred in 1990 when Iraq, facing international isolation after invading Kuwait on August 2, restored diplomatic ties with Iran on September 10 to secure neutrality or support against the U.S.-led coalition, releasing additional POWs as a gesture.[54] This pragmatic outreach yielded a 1990 border agreement reaffirming the 1975 Algiers Accord, but relations reverted to hostility amid the Gulf War and subsequent sanctions on Iraq, with Iran backing anti-Saddam opposition groups.[55] Sustained normalization only accelerated after the 2003 U.S. invasion toppled Saddam, enabling Iran to extend influence over Iraq's Shiite-majority government through economic ties, pilgrimage routes, and militia networks, though low-level border skirmishes and ideological frictions lingered.[56] Resolution 598 thus provided a framework for de-escalation but did not eradicate animosities rooted in sectarian divides, territorial claims, and proxy competitions, as evidenced by ongoing Iranian support for Iraqi militias into the 2020s.[57]Lessons for UN Security Council Efficacy

The implementation of Resolution 598 demonstrated that United Nations Security Council resolutions under Chapter VII, while legally binding, often face significant delays in efficacy due to non-compliance by warring parties without accompanying enforcement mechanisms such as sanctions or military action. Adopted unanimously on July 20, 1987, the resolution demanded an immediate ceasefire and troop withdrawals, yet Iran rejected it initially, citing "fundamental defects" including the absence of explicit attribution of aggression to Iraq, and only accepted it on July 18, 1988, following severe military setbacks and the U.S. Navy's downing of Iran Air Flight 655 on July 3, 1988. Iraq, despite prompt acceptance, exploited the delay to launch offensives, accepting the ceasefire on August 6, 1988, under pressure from regional allies like Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Kuwait. This one-year gap underscores how battlefield dynamics and external pressures, rather than the resolution alone, compelled adherence, revealing the UNSC's reliance on parties' strategic calculations for enforcement.[58] A key lesson lies in the critical role of consensus among the five permanent members (P5) of the Security Council, whose informal consultations enabled the unanimous adoption of Resolution 598 after years of deadlock, marking a shift toward cooperative diplomacy that facilitated subsequent missions like the United Nations Iran-Iraq Military Observer Group (UNIIMOG). UNIIMOG, deployed with 350 observers from 26 countries starting August 1988, verified withdrawals but encountered implementation challenges, including movement restrictions by both sides and confirmation of only 25% of 1,960 reported ceasefire violations, highlighting logistical limitations in monitoring vast conflict zones. The absence of prior sanctions or force authorization in Resolution 598 or follow-ups further illustrates the UNSC's constraints when P5 interests diverge—earlier Soviet support for Iraq and U.S. neutrality prolonged inaction—emphasizing that efficacy improves with aligned great-power interests but falters amid divisions.[58][3] Resolution 598's partial success in halting hostilities but failure to fully resolve underlying issues, such as the mandated inquiry into war responsibility under paragraph 8, points to the UNSC's challenges in addressing root causes like aggression attribution when parties withhold cooperation. The Secretary-General's panel deemed such an inquiry premature without mutual consent, leaving responsibility unresolved and contributing to lingering tensions in Iran-Iraq relations. This outcome teaches that while the UNSC can broker ceasefires through mediation and observer missions, its impartiality is often questioned by non-compliant states—Iran perceived bias toward Iraq—undermining long-term enforcement; true efficacy requires not only diplomatic frameworks but verifiable mechanisms for accountability, ideally backed by credible threats of escalation, as seen in contrasts with later interventions like the 1990 Gulf crisis where P5 unity enabled stronger action.[2][51]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/United_Nations_Security_Council_Resolution_598