Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Visa Inc.

View on Wikipedia

Visa Inc. (/ˈviːzə, ˈviːsə/), founded in 1958, is an American multinational payment card services corporation headquartered in San Francisco, California.[2][5] It facilitates electronic funds transfers throughout the world, most commonly through Visa-branded credit cards, debit cards and prepaid cards.[6]

Key Information

Visa does not issue cards, extend credit, or set rates and fees for consumers; rather, Visa provides financial institutions with Visa-branded payment products that they then use to offer credit, debit, prepaid and cash access programs to their customers. In 2015, the Nilson Report, a publication that tracks the credit card industry, found that Visa's global network (known as VisaNet) processed 100 billion transactions during 2014 with a total volume of US$6.8 trillion.[7]

Visa was founded in 1958 by Bank of America (BofA) as the BankAmericard credit card program.[1] In response to competitor Master Charge (now Mastercard), BofA began to license the BankAmericard program to other financial institutions in 1966.[8] By 1970, BofA gave up direct control of the BankAmericard program, forming a cooperative with the other various BankAmericard issuer banks to take over its management. It was then renamed Visa in 1976.[9]

Nearly all Visa transactions worldwide are processed through the company's directly operated VisaNet at one of four secure data centers, located in Ashburn, Virginia, and Highlands Ranch, Colorado, in the United States; London, England; and in Singapore.[10] These facilities are heavily secured against natural disasters, crime, and terrorism; can operate independently of each other and from external utilities if necessary; and can handle up to 30,000 simultaneous transactions and up to 100 billion computations every second.[7][11][12]

Visa is the world's second-largest card payment organization (debit and credit cards combined), after being surpassed by China UnionPay in 2015, based on annual value of card payments transacted and number of issued cards.[13] However, because UnionPay's size is based primarily on the size of its domestic market in China, Visa is still considered the dominant bankcard company in the rest of the world, where it commands a 50% market share of total card payments.[13]

History

[edit]

On September 18, 1958, Bank of America (BofA) officially launched its BankAmericard credit card program in Fresno, California.[1] In the weeks leading up to the launch of BankAmericard, BofA had saturated Fresno mailboxes with an initial mass mailing (or "drop", as they came to be called) of 65,000 unsolicited credit cards.[1][14] BankAmericard was the brainchild of BofA's in-house product development think tank, the Customer Services Research Group, and its leader, Joseph P. Williams. Williams convinced senior BofA executives in 1956 to let him pursue what became the world's first successful mass mailing of unsolicited credit cards (actual working cards, not mere applications) to a large population.[15]

Williams' pioneering accomplishment was that he brought about the successful implementation of the all-purpose credit card (in the sense that his project was not canceled outright), not in coming up with the idea.[15] By the mid-1950s, the typical middle-class American already maintained revolving credit accounts with several different merchants, which was clearly inconvenient and inefficient due to the need to carry so many cards and pay so many separate bills each month.[16] The need for a unified financial instrument was already evident to the American financial services industry, but no one could figure out how to do it. There were already charge cards like Diners Club (which had to be paid in full at the end of each billing cycle), and "by the mid-1950s, there had been at least a dozen attempts to create an all-purpose credit card."[16] However, these prior attempts had been carried out by small banks which lacked the resources to make them work.[16] Williams and his team studied these failures carefully and believed they could avoid replicating those banks' mistakes; they also studied existing revolving credit operations at Sears and Mobil Oil to learn why they were successful.[16] Fresno was selected for its population of 250,000 (big enough to make a credit card work, small enough to control initial startup cost), BofA's market share of that population (45%), and relative isolation, to control public relations damage in case the project failed.[17] According to Williams, Florsheim Shoes was the first major retail chain which agreed to accept BankAmericard at its stores.[18]

The 1958 test at first went smoothly, but then BofA panicked when it confirmed rumors that another bank was about to initiate its own drop in San Francisco, BofA's home market.[19] By March 1959, drops began in San Francisco and Sacramento; by June, BofA was dropping cards in Los Angeles; by October, the entire state of California had been saturated with over 2 million credit cards and BankAmericard was being accepted by 20,000 merchants.[19] However, the program was riddled with problems, as Williams (who had never worked in a bank's loan department) had been too earnest and trusting in his belief in the basic goodness of the bank's customers, and he resigned in December 1959. Twenty-two percent of accounts were delinquent, not the 4% expected, and police departments around the state were confronted by numerous incidents of the brand new crime of credit card fraud.[20] Both politicians and journalists joined the general uproar against Bank of America and its newfangled credit card, especially when it was pointed out that the cardholder agreement held customers liable for all charges, even those resulting from fraud.[21] BofA officially lost over $8.8 million on the launch of BankAmericard, but when the full cost of advertising and overhead was included, the bank's actual loss was probably around $20 million.[21]

However, after Williams and some of his closest associates left, BofA management realized that BankAmericard was salvageable.[22] They conducted a "massive effort" to clean up after Williams, imposed proper financial controls, published an open letter to 3 million households across the state apologizing for the credit card fraud and other issues their card raised and eventually were able to make the new financial instrument work.[22] By May 1961, the BankAmericard program became profitable for the first time.[23] At the time, BofA deliberately kept this information secret and allowed then-widespread negative impressions to linger in order to ward off competition. This strategy worked until 1966, when BankAmericard's profitability had become far too big to hide.[24]

The original goal of BofA was to offer the BankAmericard product across California, but in 1966, BofA began to sign licensing agreements with a group of banks outside of California, in response to a new competitor, Master Charge (now Mastercard), which had been created by an alliance of several regional bankcard associations to compete against BankAmericard. BofA itself (like all other U.S. banks at the time) could not expand directly into other states due to federal restrictions not repealed until 1994. Over the following 11 years, various banks licensed the card system from Bank of America, thus forming a network of banks backing the BankAmericard system across the United States.[8] The "drops" of unsolicited credit cards continued unabated, thanks to BofA and its licensees and competitors until they were outlawed in 1970,[25] but not before over 100 million credit cards had been distributed into the American population.[26]

During the late 1960s, BofA also licensed the BankAmericard program to banks in several other countries, which began issuing cards with localized brand names. For example:[citation needed]

- In Canada, an alliance of banks (including Toronto-Dominion Bank, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, Royal Bank of Canada, Banque Canadienne Nationale and Bank of Nova Scotia) issued credit cards under the Chargex name from 1968 to 1977.

- In France, it was known as Carte Bleue (Blue Card). The logo still appears on many French-issued Visa cards today.

- In Japan, The Sumitomo Bank issued BankAmericards through the Sumitomo Credit Service.

- In the UK, the only BankAmericard issuer for some years was Barclaycard. The branding still exists today, but is used not only on Visa cards issued by Barclays, but on its MasterCard and American Express cards as well.[27]

- In Spain until 1979 the only issuer was Banco de Bilbao.

In 1968, a manager at the National Bank of Commerce (later Rainier Bancorp), Dee Hock, was asked to supervise that bank's launch of its own licensed version of BankAmericard in the Pacific Northwest market. Although Bank of America had cultivated the public image that BankAmericard's troubled startup issues were now safely in the past, Hock realized that the BankAmericard licensee program itself was in terrible disarray because it had developed and grown very rapidly in an ad hoc fashion. For example, "interchange" transaction issues between banks were becoming a very serious problem, which had not been seen before when Bank of America was the sole issuer of BankAmericards. Hock suggested to other licensees that they form a committee to investigate and analyze the various problems with the licensee program; they promptly made him the chair of that committee.[28]

After lengthy negotiations, the committee led by Hock was able to persuade Bank of America that a bright future lay ahead for BankAmericard — outside Bank of America. In June 1970, Bank of America gave up control of the BankAmericard program. The various BankAmericard issuer banks took control of the program, creating National BankAmericard Inc. (NBI), an independent Delaware corporation which would be in charge of managing, promoting and developing the BankAmericard system within the United States.[29] In other words, BankAmericard was transformed from a franchising system into a jointly controlled consortium or alliance, like its competitor Master Charge. Hock became NBI's first president and CEO.[30]

However, Bank of America retained the right to directly license BankAmericard to banks outside the United States and continued to issue and support such licenses. By 1972, licenses had been granted in 15 countries.[31] The international licensees soon encountered a variety of problems with their licensing programs, and they hired Hock as a consultant to help them restructure their relationship with BofA as he had done for the domestic licensees. As a result, in 1974, the International Bankcard Company (IBANCO), a multinational member corporation, was founded in order to manage the international BankAmericard program.[32]

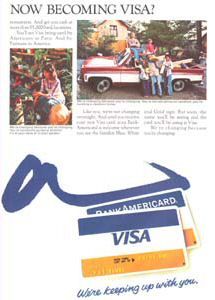

In 1976, the directors of IBANCO determined that bringing the various international networks together into a single network with a single name internationally would be in the best interests of the corporation; however, in many countries, there was still great reluctance to issue a card associated with Bank of America, even though the association was entirely nominal in nature. For this reason, in 1976, BankAmericard, Barclaycard, Carte Bleue, Chargex, Sumitomo Card, and all other licensees united under the new name, "Visa",[33] which retained the distinctive blue, white and gold flag. NBI became Visa USA and IBANCO became Visa International.[9]

The term Visa was conceived by the company's founder, Dee Hock. He believed that the word was instantly recognizable in many languages in many countries and that it also denoted universal acceptance.[34]

The announcement of the transition came on December 16, 1976, with VISA cards to replace expiring BankAmericard cards starting on March 1, 1977 (initially with both the BankAmericard name and the VISA name on the same card), and the various Bank of America issued cards worldwide being phased out by the end of October 1979.[35]

In October 2007, Bank of America announced it was resurrecting the BankAmericard brand name as the "BankAmericard Rewards Visa".[36]

In March 2022, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Visa announced that it would suspend all business operations in Russia.[37]

Corporate structure

[edit]Prior to October 3, 2007, Visa comprised four non-stock, separately incorporated companies that employed 6,000 people worldwide: the worldwide parent entity Visa International Service Association (Visa), Visa USA Inc., Visa Canada Association, and Visa Europe Ltd. The latter three separately incorporated regions had the status of group members of Visa International Service Association.[citation needed]

The unincorporated regions Visa Latin America (LAC), Visa Asia Pacific and Visa Central and Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa (CEMEA) were divisions within Visa.[citation needed]

Billing and finance charge methods

[edit]Initially, signed copies of sales drafts were included in each customer's monthly billing statement for verification purposes—an industry practice known as "country club billing".[38] By the late 1970s, however, billing statements no longer contained these enclosures, but rather a summary statement showing posting date, purchase date, reference number, merchant name, and the dollar amount of each purchase.[38] At the same time, many issuers, particularly Bank of America, were in the process of changing their methods of finance charge calculation. Initially, a "previous balance" method was used—calculation of finance charge on the unpaid balance shown on the prior month's statement.[38] Later, it was decided to use "average daily balance" which resulted in increased revenue for the issuers by calculating the number of days each purchase was included on the prior month's statement. Several years later, "new average daily balance"—in which transactions from previous and current billing cycles were used in the calculation—was introduced. By the early 1980s, many issuers introduced the concept of the annual fee as yet another revenue enhancer.[citation needed]

IPO and restructuring

[edit]On October 11, 2006, Visa announced that some of its businesses would be merged and become a publicly traded company, Visa Inc.[39][40][41] Under the IPO restructuring, Visa Canada, Visa International, and Visa USA were merged into the new public company. Visa's Western Europe operation became a separate company, owned by its member banks who will also have a minority stake in Visa Inc.[42] In total, more than 35 investment banks participated in the deal in several capacities, most notably as underwriters.

On October 3, 2007, Visa completed its corporate restructuring with the formation of Visa Inc. The new company was the first step towards Visa's IPO.[43] The second step came on November 9, 2007, when the new Visa Inc. submitted its $10 billion IPO filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).[44] On February 25, 2008, Visa announced it would go ahead with an IPO of half its shares.[45] The IPO took place on March 18, 2008. Visa sold 406 million shares at US$44 per share ($2 above the high end of the expected $37–42 pricing range), raising US$17.9 billion in what was then the largest initial public offering in U.S. history.[46] On March 20, 2008, the IPO underwriters (including JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs & Co., Bank of America Securities LLC, Citi, HSBC, Merrill Lynch & Co., UBS Investment Bank and Wachovia Securities) exercised their overallotment option, purchasing an additional 40.6 million shares, bringing Visa's total IPO share count to 446.6 million, and bringing the total proceeds to US$19.1 billion.[47] Visa now trades under the ticker symbol "V" on the New York Stock Exchange.[48]

Visa Europe

[edit]Visa Europe Ltd. was a membership association and cooperative of over 3,700 European banks and other payment service providers[49] that operated Visa branded products and services within Europe. Visa Europe was a company entirely separate from Visa Inc. having gained independence of Visa International Service Association in October 2007 when Visa Inc. became a publicly traded company on the New York Stock Exchange.[50] Visa Inc. announced the plan to acquire Visa Europe on November 2, 2015, creating a single global company.[51] On April 21, 2016, the agreement was amended in response to the feedback of European Commission.[52] The acquisition of Visa Europe was completed on June 21, 2016.[53]

Failed acquisition of Plaid

[edit]On January 13, 2020, Plaid announced that it had signed a definitive agreement to be acquired by Visa for $5.3 billion.[54][55] The deal was double the company's most recent Series C round valuation of $2.65 billion,[56] and was expected to close in the next 3–6 months, subject to regulatory review and closing conditions. According to the deal, Visa would pay $4.9 billion in cash and approximately $400 million of retention equity and deferred equity,[57] according to a presentation deck prepared by Visa.[58]

On November 5, 2020, the United States Department of Justice filed a lawsuit seeking to block the acquisition, arguing that Visa is a monopolist trying to eliminate a competitive threat by purchasing Plaid. Visa said it disagreed with the lawsuit and "intends to defend the transaction vigorously."[59][60] On January 12, 2021, Visa and Plaid announced they had abandoned the deal.[61]

Digital currencies

[edit]On February 3, 2021, Visa announced a partnership with First Boulevard, a neobank promoting cryptocurrency, which has been touted as a means of building generational wealth for Black Americans.[62] The partnership would allow their users to buy, sell, hold, and trade digital assets through Anchorage Digital.[63][64]

On March 29, 2021, Visa announced the acceptance of stablecoin USDC to settle transactions on its network.[65]

Visa Foundation

[edit]Registered in the United States as a 501(c)(3) entity, the Visa Foundation was created with the mission of supporting inclusive economies. In particular, economies in which individuals, businesses and communities can thrive with the support of grants and investments. Supporting resiliency, as well as the growth, of micro and small businesses that benefit women is a priority of the Visa Foundation. Furthermore, the Foundation prioritizes providing support to the community from a broad standpoint, as well as responding to disasters during crisis.[66]

Other initiatives

[edit]In December 2020, Visa Announced the launch of a new accelerator program across Asia Pacific to further develop the region's financial technology ecosystem.[67] The accelerator program aims to find and partner with startup companies providing financial and payments technologies that could potentially leverage on Visa's network of bank and merchant partners in the region.[68]

Finance

[edit]| Region | Sales in billion $ | share |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 14.1 | 43.3% |

| International | 18.5 | 56.7% |

For the fiscal year 2022, Visa reported earnings of US$14.96 billion, with an annual revenue of US$29.31 billion, an increase of 21.6% over the previous fiscal cycle. As of 2022, the company ranked 147th on the Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by revenue.[70] Visa's shares traded at over $143 per share, and its market capitalization was valued at over US$280.2 billion in September 2018.

| Year | Revenue in million US$ |

Net income in million US$ |

Employees |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005[71] | 2,665 | 360 | |

| 2006[71] | 2,948 | 455 | |

| 2007[71] | 3,590 | −1,076 | 5,479 |

| 2008[71] | 6,263 | 804 | 5,765 |

| 2009[72] | 6,911 | 2,353 | 5,700 |

| 2010[73] | 8,065 | 2,966 | 6,800 |

| 2011[74] | 9,188 | 3,650 | 7,500 |

| 2012[75] | 10,421 | 2,144 | 8,500 |

| 2013[76] | 11,778 | 4,980 | 9,600 |

| 2014[77] | 12,702 | 5,438 | 9,500 |

| 2015[78] | 13,880 | 6,328 | 11,300 |

| 2016[79] | 15,082 | 5,991 | 11,300 |

| 2017[80] | 18,358 | 6,699 | 12,400 |

| 2018[81] | 20,609 | 10,301 | 15,000 |

| 2019[82] | 22,977 | 12,080 | 19,500 |

| 2020[82] | 21,846 | 10,866 | 20,500 |

| 2021[83] | 24,105 | 12,311 | 21,500 |

| 2022[84] | 29,310 | 14,957 | 26,500 |

| 2023[85] | 32,653 | 17,273 | 28,800 |

| 2024[4] | 35,926 | 19,743 | 31,600 |

Criticism and controversy

[edit]WikiLeaks

[edit]Visa Europe began suspending payments to WikiLeaks on December 7, 2010.[86] The company said it was awaiting an investigation into 'the nature of its business and whether it contravenes Visa operating rules' – though it did not go into details.[87] In return DataCell, the IT company that enables WikiLeaks to accept credit and debit card donations, announced that it would take legal action against Visa Europe.[88] On December 8, the group Anonymous performed a DDoS attack on visa.com,[89] bringing the site down.[90] Although the Norway-based financial services company Teller AS, which Visa ordered to look into WikiLeaks and its fundraising body, the Sunshine Press, found no proof of any wrongdoing, Salon reported in January 2011 that Visa Europe "would continue blocking donations to the secret-spilling site until it completes its own investigation".[87]

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay stated that Visa may be "violating WikiLeaks' right to freedom of expression" by withdrawing their services.[91]

In July 2012, the Reykjavík District Court in Iceland decided that Valitor (the Icelandic partner of Visa and MasterCard) was violating the law when it prevented donations to the site by credit card. It was ruled that the donations be allowed to return to the site within 14 days or they would be fined in the amount of US$6,000 per day.[92]

Litigation and regulatory actions

[edit]United States

[edit]Antitrust lawsuit by ATM operators

[edit]In 2011, MasterCard and Visa were sued in a class action by ATM operators claiming the credit card networks' rules effectively fix ATM access fees.[93] The suit claimed that this is a restraint on trade in violation of US federal law. The lawsuit was filed by the National ATM Council and independent operators of automated teller machines. More specifically, it is alleged that MasterCard's and Visa's network rules prohibit ATM operators from offering lower prices for transactions over PIN-debit networks that are not affiliated with Visa or MasterCard. The suit says that this price-fixing artificially raises the price that consumers pay using ATMs, limits the revenue that ATM-operators earn, and violates the Sherman Act's prohibition against unreasonable restraints of trade.

Johnathan Rubin, an attorney for the plaintiffs said, "Visa and MasterCard are the ringleaders, organizers, and enforcers of a conspiracy among U.S. banks to fix the price of ATM access fees in order to keep the competition at bay."[94]

In 2017, a US district court denied the ATM operators' request to stop Visa from enforcing the ATM fees.[95]

Debit card swipe fees

[edit]In 1996, a class of U.S. merchants, including Walmart, brought an antitrust lawsuit against Visa and MasterCard over their "Honor All Cards" policy, which forced merchants who accepted Visa and MasterCard branded credit cards to also accept their respective debit cards (such as the "Visa Check Card"). Over 4 million class members were represented by the plaintiffs. According to a website associated with the suit,[96] Visa and MasterCard settled the plaintiffs' claims in 2003 for a total of $3.05 billion. Visa's share of this settlement is reported to have been the larger.[citation needed]

U.S. Justice Department actions

[edit]In 1998, the U.S. Department of Justice sued Visa over rules prohibiting its issuing banks from doing business with American Express and Discover.[97] The Department of Justice won its case at trial in 2001 and the verdict was upheld on appeal. American Express and Discover filed suit as well.[98]

In October 2010, Visa and MasterCard reached a settlement with the Department of Justice in another antitrust case. The companies agreed to allow merchants displaying their logos to decline certain types of cards (because interchange fees differ), or to offer consumers discounts for using cheaper cards.[99]

Payment card interchange fee and merchant discount antitrust litigation

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (December 2024) |

On November 27, 2012, a federal judge entered an order granting preliminary approval to a proposed settlement to a class-action lawsuit[100] filed in 2005 by merchants and trade associations against Mastercard and Visa. The suit was filed due to alleged price-fixing practices employed by Mastercard and Visa. About one-quarter of the named class plaintiffs have decided to opt "out of the settlement". Opponents object to provisions that would bar future lawsuits and even prevent merchants from opting out of significant portions of the proposed settlement.[101]

Plaintiffs allege that Visa and Mastercard fixed interchange fees, also known as swipe fees, that are charged to merchants for the privilege of accepting payment cards. In their complaint, the plaintiffs also alleged that the defendants unfairly interfere with merchants from encouraging customers to use less expensive forms of payment such as lower-cost cards, cash, and checks.[101]

A settlement of US$6.24 billion has been reached and a court is scheduled to approve or deny the agreement on November 7, 2019.[102]

Confrontation with Walmart over high fees

[edit]In June 2016, the Wall Street Journal reported that Walmart threatened to stop accepting Visa cards in Canada. Visa objected saying that consumers should not be dragged into a dispute between the companies.[103] In January 2017, Walmart Canada and Visa reached a deal to allow the continued acceptance of Visa.[104]

Dispute with Kroger over high credit card fees

[edit]In March 2019, U.S. retailer Kroger announced that its 250-strong Smith's chain would stop accepting Visa credit cards as of April 3, 2019, due to the cards' high swipe fees. Kroger's California-based Foods Co stores stopped accepting Visa cards in August 2018. Mike Schlotman, Kroger's executive vice president/chief financial officer, said Visa had been "misusing its position and charging retailers excessive fees for a long time." In response, Visa issued a statement saying it was "unfair and disappointing that Kroger is putting shoppers in the middle of a business dispute."[105] As of October 31, 2019, Kroger has settled their dispute with Visa and is now accepting the payment method.[106]

2020 Antitrust lawsuit challenging acquisition of Plaid

[edit]In January 2020 Visa announced it would acquire Plaid for $5.3 billion.[107][108] In November 2020, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) sued to block Visa's acquisition of fintech startup Plaid, claiming that the merger would violate antitrust laws. The DOJ argues that the merger would eliminate Plaid's potential ability to compete in the online debit market, thereby creating a monopoly for Visa.[109] Visa CEO at the time Alfred Kelly described the acquisition bid as an "insurance policy" to neutralize a "threat to our important US debit business."[110] In January 2021, Visa along with Plaid both mutually agreed to abandon its proposed acquisition.[111]

2021 Antitrust investigation over debit card practices

[edit]In March 2021, the United States Justice Department announced its investigation with Visa to discover if the company is engaging in anticompetitive practices in the debit card market. The main question at hand is whether or not Visa is limiting merchants' ability to route debit card transactions over card networks that are often less expensive, focusing more so on online debit card transactions. The probe highlights the role of network fees, which are invisible to consumers and place pressure on merchants, who mitigate the fees by raising prices of goods for customers. The probe was confirmed through a regulatory filing on March 19, 2021, stating they will be cooperating with the Justice Department. Visa's shares fell more than 6% following the announcement.[112][113][114][115] On September 24, 2024, the Justice Department sued Visa, alleging that Visa used illegal tactics to maintain a monopoly in debit-card payments.[116]

Outside of the United States

[edit]Anti-competitive conduct in Australia

[edit]In 2015, the Australian Federal Court ordered Visa to pay a pecuniary penalty of $20 million (including legal fees) for engaging in anti-competitive conduct against dynamic currency conversion operators, in proceedings brought by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.[117]

Antitrust issues in Europe

[edit]In 2002, the European Commission exempted Visa's multilateral interchange fees from Article 81 of the EC Treaty that prohibits anti-competitive arrangements.[118] However, this exemption expired on December 31, 2007. In the United Kingdom, Mastercard has reduced its interchange fees while it is under investigation by the Office of Fair Trading.

In January 2007, the European Commission issued the results of a two-year inquiry into the retail banking sector. The report focuses on payment cards and interchange fees. Upon publishing the report, Commissioner Neelie Kroes said the "present level of interchange fees in many of the schemes we have examined does not seem justified." The report called for further study of the issue.[119]

On March 26, 2008, the European Commission opened an investigation into Visa's multilateral interchange fees for cross-border transactions within the EEA as well as into the "Honor All Cards" rule (under which merchants are required to accept all valid Visa-branded cards).[120][needs update]

The antitrust authorities of EU member states (other than the United Kingdom) also investigated Mastercard's and Visa's interchange fees. For example, on January 4, 2007, the Polish Office of Competition and Consumer Protection fined twenty banks a total of PLN 164 million (about $56 million) for jointly setting Mastercard's and Visa's interchange fees.[121][122]

In December 2010, Visa reached a settlement with the European Union in yet another antitrust case, promising to reduce debit card payments to 0.2 percent of a purchase.[123] A senior official from the European Central Bank called for a break-up of the Visa/Mastercard duopoly by creation of a new European debit card for use in the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA).[124] After Visa's blocking of payments to WikiLeaks, members of the European Parliament expressed concern that payments from European citizens to a European corporation could apparently be blocked by the US, and called for a further reduction in the dominance of Visa and Mastercard in the European payment system.[125]

High swipe fees in Poland

[edit]Visa's interchange fee of 1.5–1.6% in Poland started discussion about the need for increased government regulation surrounding the topic.[126] The high fees encouraged merchants to create new payment systems, which avoid using Visa as a middleman. For example, mobile applications were created by major banks,[127] proprietary payment systems were created by franchises,[128] and public transport authorities created ticketing systems.[129]

UK Payment System Regulator

[edit]In May 2024, the UK Payment Systems Regulator (PSR) proposed new rules requiring Visa and Mastercard to increase transparency regarding the fees they charge merchants. The proposed regulations mandate that the two companies, regularly disclose detailed financial information to the PSR. The regulations also require Visa and Mastercard to consult with merchants and retailers before implementing any fee changes.[130]

The proposal followed a PSR review revealing that Visa and Mastercard had raised their scheme and processing fees by more than 30% in real terms over the previous five years. Despite these increases, the PSR found limited evidence that service quality had improved proportionately.[131]

European Commission investigation into scheme fees

[edit]In November 2024, the European Commission launched a further investigation into whether the scheme fees imposed by Visa and Mastercard impact negatively on retailers. Some retailers had in recent years complained about the fees, citing a lack of transparency.[132] The Commission took its investigation further in June 2025, asking for a retailer view and for comments from the card operators about whether "a standardized summary of fees" would help to promote transparency.[133]

Corporate affairs

[edit]Headquarters

[edit]

Visa was traditionally headquartered in San Francisco until 1985, when it moved to San Mateo.[134] Around 1993, Visa began consolidating various scattered offices in San Mateo to a location in nearby Foster City.[134] Visa became Foster City's largest employer.

In 2009, Visa moved its corporate headquarters back to San Francisco when it leased the top three floors of the 595 Market Street office building, although most of its employees remained at its Foster City campus.[135] In 2012, Visa decided to consolidate its headquarters in Foster City where 3,100 of its 7,700 global workers are employed.[136] Visa owns four buildings at the intersection of Metro Center Boulevard and Vintage Park Drive.

As of October 1, 2012, Visa's headquarters were located in Foster City.[136] In December 2012, Visa Inc. confirmed that it will build a global information technology center off of the US 183 Expressway in northwest Austin, Texas.[137] By 2019, Visa had leased space in four buildings near Austin and employed nearly 2,000 people.[138]

On November 6, 2019, Visa announced plans to move its headquarters back to San Francisco by 2024 upon completion of a new "13-story, 300,000-square-foot building".[139] Visa also announced that it would redesign its current four-building complex in Foster City to 575,000 square feet, for offices for 3,000 employees in its product and technology teams.[139] The existing complex has over 970,000 square feet of space, but Visa declined to explain how it would dispose of almost 400,000 square feet of excess space.[139]

On June 6, 2024, Visa opened its new headquarters building at 300 Toni Stone Crossing in the Mission Rock development in San Francisco's Mission Bay neighborhood.[2][140] The building was officially designated as the Market Support Center on its opening date, rather than a "headquarters" building as indicated in its original 2019 announcement.[140] The company's 2024 filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission designate a post office box as its official address.[140] Despite that ambiguity, the office of Visa's chief executive officer is based in the Market Support Center.[140] The building features outdoor terraces, a rooftop deck, and views of San Francisco Giants baseball games and other events at Oracle Park across McCovey Cove.[140]

Ownership

[edit]Visa is mainly owned by institutional investors, who own over 95% of shares. The largest shareholders in December 2023 were:[141]

- The Vanguard Group (8.94%)

- BlackRock (7.99%)

- State Street Corporation (4.64%)

- Fidelity Investments (3.26%)

- Morgan Stanley (3.26%)

- T. Rowe Price (2.85%)

- Geode Capital Management (2.15%)

- Bank of America (1.53%)

- AllianceBernstein (1.46%)

- Capital International Investors (1.45%)

Operations

[edit]Visa offers through its issuing members the following types of cards:

- Debit cards (pay from a checking/savings account)

- Credit cards (pay monthly payments with or without interest depending on a customer paying on time)

- Prepaid cards (pay from a cash account that has no check writing privileges)

Visa operates the Plus automated teller machine network and the Interlink EFTPOS point-of-sale network, which facilitate the "debit" protocol used with debit cards and prepaid cards. They also provide commercial payment solutions for small businesses, midsize and large corporations, and governments.[142]

Visa teamed with Apple in September 2014, to incorporate a new mobile wallet feature into Apple's new iPhone models, enabling users to more readily use their Visa, and other credit/debit cards.[143]

Operating regulations

[edit]Visa has a set of rules that govern the participation of financial institutions in its payment system. Acquiring banks are responsible for ensuring that their merchants comply with the rules.

Rules address how a cardholder must be identified for security, how transactions may be denied by the bank, and how banks may cooperate for fraud prevention, and how to keep that identification and fraud protection standard and non-discriminatory. Other rules govern what creates an enforceable proof of authorization by the cardholder.[144]

The rules generally prohibit merchants from imposing a minimum or maximum purchase amount in order to accept a Visa card and from charging cardholders a fee for using a Visa card, but rules and laws vary by country.[144]

Rules in the United States

[edit]Court decisions, legal settlements, and state statutes regulating surcharges and fees vary across the United States.[145] It is illegal in three U.S. states and one territory (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, and Puerto Rico) for merchants to impose surcharges for the use of a credit card.[146][147] In those U.S. states where surcharges are permitted by law, merchants wishing to apply surcharges are required to abide by rules set by Visa.[148]

Visa permits merchants to ask for photo ID, although the merchant rule book states that merchants are not generally allowed to require photo ID to complete a transaction. However, Visa may grant a merchant permission to require photo ID for purposes of fraud control.[144]

The Dodd–Frank Act allows U.S. merchants to set a minimum purchase amount on credit card transactions, not to exceed $10.[149][150]

Rules outside the United States

[edit]Some countries have banned the no-surcharge rule, most notably in Australia[151] retailers may apply surcharges to any credit-card transaction, Visa or otherwise. In the UK the law was changed in January 2018 to prevent retailers from adding a surcharge to a transaction as per 'The Consumer Rights (Payment Surcharges) Regulations 2012'.

Transaction security

[edit]Other complications include the addition of exceptions for non-signed purchases by telephone or on the Internet and an additional security system called "Verified by Visa" for purchases on the Internet.

In September 2014, Visa Inc, launched a new service to replace account information on plastic cards with tokens – a digital account number.[152]

Products

[edit]Visa Credit Cards

[edit]Depending on the geographical location, Visa card issuers issue the following tiers of cards, from the lowest to the highest:[153]

- Traditional/Classic/Standard

- Gold

- Platinum

- Premier (France only)

- Signature (Worldwide except Canada)[154]

- Infinite

- Infinite Privilege (Canada, Brazil only)[155]

Visa Debit

[edit]This is the standard Visa-branded debit card.

Visa Electron

[edit]A Visa-branded debit card issued worldwide since the 1990s. Its distinguishing feature is that it does not allow "card not present" transactions while its floor limit is set to zero, which triggers automatic authorisation of each transaction with the issuing bank and effectively makes it impossible for the user to overdraw the account. The card has often been issued to younger customers or those who may pose a risk of overdrawing the account. Since mid-2000s, the card has mostly been replaced by Visa Debit.

Visa Cash

[edit]A Visa-branded stored-value card.

Visa Contactless (Visa payWave)

[edit]

In September 2007, Visa introduced Visa payWave (later known as Visa Contactless), a contactless payment technology feature that allows cardholders to wave their card in front of contactless payment terminals without the need to physically swipe or insert the card into a point-of-sale device.[156] This is similar to the Mastercard Contactless service and the American Express ExpressPay, with both using RFID technology. All of them uses the same EMV Contactless logo to denote the capability of the card.

In Europe, Visa has introduced the V Pay card, which is a chip-only and PIN-only debit card.[157] In Australia, take up has been the highest in the world, with more than 50% of in store Visa transactions made by Visa payWave in 2016.[158]

mVisa

[edit]mVisa is a mobile payment app allowing payment via smartphones using QR code. This QR code payment method was first introduced in India in 2015. It was later expanded to a number of other countries, including in Africa and South East Asia.[159][160]

Visa Checkout

[edit]In 2013, Visa launched Visa Checkout, an online payment system that removes the need to share card details with retailers. The Visa Checkout service allows users to enter all their personal details and card information, then use a single username and password to make purchases from online retailers. The service works with Visa credit, debit, and prepaid cards. On November 27, 2013, V.me went live in the UK, France, Spain and Poland, with Nationwide Building Society being the first financial institution in Britain to support it,[161] although Nationwide subsequently withdrew this service in 2016.

Visa Commerce Network

[edit]After Visa's acquisition of TrialPay on February 27, 2015,[162] Visa created the Visa Commerce Network. Visa Commerce Network provides businesses the ability to provide rewards, through the use of loyalty programs.

Trademark and design

[edit]Logo design

[edit]The blue and gold in Visa's logo were chosen to represent the blue sky and gold-colored hills of California, where the Bank of America was founded.

In 2005, Visa changed its logo, removing the horizontal stripes in favor of a simple white background with the name Visa in blue with an orange flick on the 'V'.[163] The orange flick was removed in favor of the logo being a solid blue gradient in 2014 and solid blue in 2021. In 2015, the gold and blue stripes were restored as card branding on Visa Debit and Visa Electron, although not as the company's logotype.[164]

Card design

[edit]

In 1983, most Visa cards around the world began to feature a hologram of a dove on its face, generally under the last four digits of the Visa number. This was implemented as a security feature – true holograms would appear three-dimensional and the image would change as the card was turned.[165] At the same time, the Visa logo, which had previously covered the whole card face, was reduced in size to a strip on the card's right incorporating the hologram. This allowed issuing banks to customize the appearance of the card. Similar changes were implemented with MasterCard cards. Today, cards may be co-branded with various merchants, airlines, etc., and marketed as "reward cards".

On older Visa cards, holding the face of the card under an ultraviolet light will reveal the dove picture, dubbed the Ultra-Sensitive Dove,[166] as an additional security test. (On newer Visa cards, the UV dove is replaced by a small V over the Visa logo.)

Beginning in 2005, the Visa standard was changed to allow for the hologram to be placed on the back of the card, or to be replaced with a holographic magnetic stripe ("HoloMag").[167] The HoloMag card was shown to occasionally cause interference with card readers, so Visa eventually withdrew designs of HoloMag cards and reverted to traditional magnetic strips.[168]

Signatures

[edit]Visa made a statement on January 12, 2018, that the signature requirement would become optional for all EMV contact or contactless chip-enabled merchants in North America starting in April 2018. It was noted that the signatures are no longer necessary to fight fraud and the fraud capabilities have advanced allowing this elimination leading to a faster in-store purchase experience.[169] Visa was the last of the major credit card issuers to relax the signature requirements. The first to eliminate the signature was MasterCard Inc. followed by Discover Financial Services and American Express Co.[170]

Sponsorships

[edit]Olympics and Paralympics

[edit]- Visa has been a worldwide sponsor of the Olympic Games since 1986 and the International Paralympic Committee since 2002. Visa is the only card accepted at all Olympic and Paralympic venues. Its current contract with the International Olympic Committee and International Paralympic Committee as the exclusive services sponsor will continue through 2032 and 2020 respectively.[171][172] This includes the Singapore 2010 Youth Olympic Games, London 2012 Olympic Games, the Sochi 2014 Olympic Winter Games, the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Olympic Games, the 2018 PyeongChang Olympic Winter Games, the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, and the Beijing 2022 Olympic Winter Games.

- In 2002, Visa became the first global sponsor of the IPC.[173] Visa extended its partnership with the International Paralympic Committee through 2020,[174] which includes the 2010 Vancouver Paralympic Winter Games, the 2012 London Paralympic Games, 2014 Sochi Paralympic Games, 2018 Pyeongchang Paralympic Games, 2020 Tokyo Paralympic Games and 2022 Beijing Paralympic Games.

Others

[edit]

- Visa was the jersey sponsor of Argentina's national basketball team at the 2015 FIBA Americas Championship in Mexico City.[175]

- Visa is the shirt sponsor for the Argentina national rugby union team, nicknamed the Pumas. Also, Visa sponsors the Copa Libertadores and the Copa Sudamericana, the most important football club tournaments in South America.

- Since 1995, Visa has sponsored the U.S. National Football League (NFL) and a number of NFL teams, including the San Francisco 49ers whose practice jerseys display the Visa logo.[176] Visa's sponsorship of the NFL extended through the 2014 season.[177]

- Until 2005, Visa was the exclusive sponsor of the Triple Crown thoroughbred tournament.

- Visa sponsored the Rugby World Cup first from the 1995 Rugby World Cup was held in South Africa until 12 years later, when the 2007 Rugby World Cup, was held in France.[178]

- In 2007, Visa became the sponsor of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa. The FIFA partnership provides Visa with global rights to a broad range of FIFA activities – including both the 2010 and 2014 FIFA World Cup and the FIFA Women's World Cup.

- Starting from the 2012 season, Visa became a partner of the Caterham F1 Team. Visa is also known for motorsport sponsorship in the past: it sponsored PacWest Racing's IndyCar team in 1995 and 1996, with drivers Danny Sullivan and Mark Blundell respectively.[179]

- Visa was a jersey sponsor of professional gaming (esports) team SK Gaming for 2017[180]

- Visa is the main sponsor of the Argentine Hockey Confederation.[181] The Visa logo is present on both the men's and women's playing kits.

- Visa and Cash App are the co-title sponsors of the rebranded Scuderia AlphaTauri Formula One team as Visa Cash App RB from 2024 onwards and will also appear in the team's F1 Academy entry. Visa also signed a sponsorship deal with Red Bull Racing.[182]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Stearns, David L. (2011). Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the Visa Electronic Payment System. London: Springer. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-84996-138-7. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023. Available through SpringerLink.

- ^ a b c Naidu (June 7, 2024). "Visa Moves Into California HQ as Part of Mixed-Use Redevelopment in Office Construction Hotspot". CoStar News. Retrieved August 4, 2024.

- ^ Harring, Alex (November 17, 2022). "Visa says Ryan McInerney will replace Al Kelly as its next CEO". CNBC. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b "U.S. SEC: Visa Inc. Form 10-K". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. November 13, 2024. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ "Visa Inc. 2021 Annual Report" (PDF). Visa Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 6, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ Visa Archived September 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ^ a b Fisher, Daniel (May 25, 2015). "Visa Moves at the Speed of Money". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2016. This article is authored by a Forbes staff member.

- ^ a b "History of Visa", Visa Latin America & Caribbean. Archived November 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Thomes, Paul (2011). Technological Innovation in Retail Finance: International Historical Perspectives. New York: Routledge. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-203-83942-3.

- ^ "Map and List of VisaNet's Data Centers". Baxtel. Archived from the original on October 19, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ Kontzer, Tony (May 29, 2013). "Inside Visa's Data Center | Network Computing". www.networkcomputing.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Swartz, Jon (March 25, 2012). "Top secret Visa data center banks on security, even has moat". USA Today. Archived from the original on November 9, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "UnionPay takes top spot from Visa in $22 trillion global cards market – RBR". Finextra. London: Finextra Research Limited. July 22, 2016. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "History of Visa". Archived from the original on October 3, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ a b Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4767-4489-6. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-4767-4489-6. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4767-4489-6. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4767-4489-6. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-4767-4489-6. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4767-4489-6. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4767-4489-6. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Nocera, Joseph (1994). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class (2013 paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4767-4489-6. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ Stearns, David L. (2011). Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the Visa Electronic Payment System. London: Springer. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-84996-138-7. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023. Available through SpringerLink.

- ^ Stearns, David L. (2011). Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the Visa Electronic Payment System. London: Springer. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-84996-138-7. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

In addition to Chase and BofA, 29 other banks started credit card systems of their own during 1958 and 1959, but nearly all of these programs failed or reported massive losses during their initial years. The terrible press from these programs further discouraged other banks from starting systems of their own, and from 1960 to 1966, only 10 more banks created new systems.

Available through SpringerLink. - ^ The Unsolicited Credit Card Act of 1970 amended the Truth in Lending Act of 1968 to ban the mailing of unsolicited credit cards. It is now codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1642.

- ^ Nocera, 15.

- ^ "Welcome to Barclaycard Cashback | Barclaycard". Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^ Nocera, 89-92.

- ^ Nocera, Joe (2013). A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-1-4767-3479-8.

- ^ Nocera, 90-93.

- ^ Stearns, David L. (2011). Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the VISA Electronic Payment System. London: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-84996-138-7.

- ^ Batiz-Lazo, Bernardo; del Angel, Gustavo (2016), "The Dawn of the Plastic Jungle: The Introduction of the Credit Card in Europe and North America, 1950-1975", Economics Working Papers, Hoover Institution: 18, archived from the original on December 22, 2016, retrieved December 21, 2016

- ^ Finel-Honigman, Irene; Sotelino, Fernando (2015). International Banking for a New Century. Oxon: Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-415-68132-2.

- ^ "VISA". The Good Schools Guide. TheGoodSchoolsGuide. February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on August 30, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ^ "BankAmericard to become Visa", The Courier-Journal (Louisville KY), December 16, 1976, p. B 10

- ^ "BofA resurrects Bankamericard brand" Archived October 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, San Francisco Business Times.

- ^ Paybarah, Azi (March 5, 2022). "Mastercard and Visa suspend operations in Russia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c Markoff, John (July 31, 1988). "American Express Goes High-Tech". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2025.

... the practice of enclosing receipts with a customer's bill, known as country club billing, has long been considered overly expensive and cumbersome ... One by one during the past decade, credit card companies dropped the practice, opting instead to mail statements that simply list billing merchants and the amounts of transactions.

- ^ Visa, Inc. Corporate Site Archived February 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Visa plans stock market flotation" Archived March 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, BBC News – Business, October 12, 2006.

- ^ Bawden, Tom. "Visa plans to split into two and float units for $13bn."[dead link], The Times, October 12, 2006.

- ^ Bruno, Joel Bel. "Visa Reveals Plan to Restructure for IPO" Archived June 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press, June 22, 2007.

- ^ "Visa, Inc. Complete Global Restructuring" Archived December 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Visa, Inc. Press Release, October 3, 2007.

- ^ "Visa files for $10 billion IPO" Archived October 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, November 9, 2007.

- ^ "Visa plans a $19 billion initial public offering" Archived August 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. The Economist. February 25, 2008.

- ^ Benner, Katie. "Visa's $15 billion IPO: Feast or famine?" Archived November 29, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Fortune via CNNMoney, March 18, 2008.

- ^ "Visa Inc. Announces Exercise of Over-Allotment Option", Visa Inc. Press Release, March 20, 2008. Archived July 21, 2012, at archive.today

- ^ "Visa IPO Seeks MasterCard Riches" Archived February 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, TheStreet.com, February 2, 2008.

- ^ "Visa Europe members exploring sale to Visa – WSJ". Reuters. March 19, 2013. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- ^ "FAQs". Visaeurope.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2013. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- ^ "Visa Inc. to Acquire Visa Europe" (Press release). November 2, 2015. Archived from the original on November 6, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ "Visa Inc. Reaches Preliminary Agreement to Amend Transaction With Visa Europe". Visa Inc. April 21, 2016. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ "Visa Inc. Completes Acquisition of Visa Europe". Visa Investor Relations (Press release). June 21, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Visa is acquiring Plaid for $5.3 billion, 2x its final private valuation". TechCrunch. January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ "With Plaid Acquisition, Visa Makes A Big Play for the 'Plumbing' That Connects the Fintech World". Fortune. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "What Plaid's $5.3 Billion Acquisition Means For The Future Of Fintech And Open Banking". finance.yahoo.com. February 21, 2020. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ Demos, Telis (January 14, 2020). "Visa's Bet on Plaid Is Costly but Necessary". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ "Visa to acquire crypto-serving fintech unicorn Plaid for $5.3B". finance.yahoo.com. January 15, 2020. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ Noonan, Laura (November 5, 2020). "US justice department sues to block Visa's $5.3bn Plaid takeover". Financial Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. sues Visa to block its acquisition of Plaid". Reuters. November 5, 2020. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Kendall, Brent; Andriotis, AnnaMaria; Rudegeair, Peter (January 12, 2021). "Visa Abandons Planned Acquisition of Plaid After DOJ Challenge". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 15, 2024.

- ^ Ellis, Nicquel Terry (August 20, 2022). "Cryptocurrency has been touted as the key to building Black wealth. But critics are skeptical". CNN. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ "Visa: Crypto API Program Makes Crypto An Economic Empowerment Tool". PYMNTS. February 3, 2021. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Visa Expands Digital Currency Roadmap with First Boulevard". Visa. February 3, 2021. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Visa Moves to Allow Payment Settlements Using Cryptocurrency". NDTV Gadgets 360. March 30, 2021. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ "Visa Launches Foundation with Inaugural Grant to Women's World Banking". Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ "Visa has launched an Accelerator Program for Fintech startups across Asia Pacific". Startup News, Networking, and Resources Hub | BEAMSTART. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Accelerator". www.visa.com.sg. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Visa, Inc.: Shareholders Board Members Managers and Company Profile | US92826C8394 | MarketScreener". www.marketscreener.com. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "Fortune 500 Companies 2022: Visa". Fortune. Archived from the original on November 17, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "2008 Annual Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "2009 Annual Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "2010 Annual Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "2011 Annual Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "2012 Annual Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "2013 Annual Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "2014 Annual Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "2015 Annual Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "2016 Annual Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Volkman, Eric (January 18, 2018). "Why 2017 was a Year to Remember for Visa Inc. -- The Motley Fool". The Motley Fool. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ "2018 Q4 Revenue and Earnings" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ a b "Visa, Inc - AnnualReports.com". www.annualreports.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ "Visa Inc. Reports Fiscal Fourth Quarter and Full-Year 2021 Results" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. SEC: Visa Inc. Form 10-K". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. November 16, 2022. Archived from the original on November 17, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. SEC: Visa Inc. Form 10-K". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. November 15, 2023. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ BBC News Archived August 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- ^ a b No proof WikiLeaks breaking law, inquiry finds, Associated Press (January 26, 2011) Archived January 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Wikileaks' IT firm says it will sue Visa and Mastercard". BBC News. December 8, 2010. Archived from the original on August 27, 2011. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- ^ "WikiLeaks supporters disrupt Visa and MasterCard sites in 'Operation Payback'". The Guardian. December 8, 2010. Archived from the original on May 8, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ Adams, Richard; Weaver, Matthew (December 8, 2010). "WikiLeaks: the day cyber warfare broke out – as it happened". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ^ UNifeed Geneva/Pillay Archived March 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, UN Web site. Retrieved on December 15, 2010.

- ^ Zetter, Kim. "WikiLeaks Wins Icelandic Court Battle Against Visa for Blocking Donations". WIRED. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on June 5, 2022. Retrieved September 15, 2024.

- ^ "Complaint, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Home Depot USA Inc" (PDF). PacerMonitor. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ "ATM Operators File Antitrust Lawsuit Against Visa and MasterCard" (Press release). PR Newswire. October 12, 2011. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ "National Atm Council, Inc. v. Visa Inc., Civil Action No. 2011-1803 (D.D.C. 2017)". Court Listener. May 22, 2017. Archived from the original on July 12, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ "Visa Check/MasterMoney Antitrust Litigation", Web Site. Archived April 28, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Justice Department Files Antitrust Suit Against Visa and MasterCard for Limiting Competition in Credit Card Network Market". United States Department of Justice. October 7, 1998. Retrieved September 15, 2024.

- ^ Duncan, Mallory (July 9, 2012). "Duncan: Credit Card Market Is Unfair, Noncompetitive". Roll Call. Retrieved September 15, 2024.

- ^ "Visa, Mastercard settlement means more flexibility for merchants". Marketplace. American Public Radio. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011.

- ^ "Class Settlement Preliminary Approval Order pg.11" (PDF). U.S. District Court. November 27, 2012. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Longstreth, Andrew (December 13, 2013). "Judge approves credit card swipe fee settlement". NBC News. Archived from the original on November 6, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Kiesche, Liz (February 22, 2019). "Visa, Mastercard $6.24B settlement gets preliminary okay from court". Seeking Alpha. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Sidel, Robin (June 16, 2016). "Visa Defends Fees in Wal-Mart Canada Dispute". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 15, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ Evans, Pete (January 5, 2017). "Walmart strikes deal with Visa to settle credit card fee dispute". CBC. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ Morris, Chris. "Kroger Bans Visa Cards at 250 Additional Stores". Fortune. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ^ Peterson, Hayley (October 30, 2019). "Kroger has reversed its ban on Visa credit cards after previously accusing the company of 'excessive fees' that 'drive up food prices'". Business Insider. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ "Visa To Acquire Plaid". usa.visa.com. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Kauflin, Jeff (January 13, 2020). "Why Visa Is Buying Fintech Startup Plaid For $5.3 Billion". Forbes. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Primack, Dan (November 5, 2020). "Justice Dept sues to block Visa from buying Plaid". Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Kendall, Brent; Andriotis, AnnaMaria (November 5, 2020). "Justice Department Files Antitrust Lawsuit Challenging Visa's Planned Acquisition of Plaid". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Surane, Jennifer (January 12, 2021). "Visa, Plaid Scrap $5.3 Billion Deal Amid U.S. Antitrust Suit". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Kendall, AnnaMaria Andriotis and Brent (March 19, 2021). "WSJ News Exclusive | Visa Faces Antitrust Investigation Over Debit-Card Practices". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ "Report: DOJ investigating Visa over debit card business". The Washington Post. Associated Press. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved March 20, 2021.[dead link]

- ^ Copeland, Brent Kendall and Rob (October 21, 2020). "Justice Department Hits Google With Antitrust Lawsuit". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Torry, AnnaMaria Andriotis and Harriet (June 21, 2020). "The Credit-Card Fees Merchants Hate, Banks Love and Consumers Pay". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Michaels, Dave; Au-Yeung, Angel (September 24, 2024). "Justice Department Sues Visa, Alleges Illegal Monopoly in Debit-Card Payments". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ Commission, Australian Competition and Consumer (September 4, 2015). "Visa ordered to pay $18 million penalty for anti-competitive conduct following ACCC action". Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ "Commission exempts multilateral interchange fees for cross-border Visa card payments" (Press release). European Commission. July 24, 2002. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ "Competition: Commission sector inquiry finds major competition barriers in retail banking" (Press release). European Commission. January 31, 2007. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ "Antitrust: Commission initiates formal proceedings against Visa Europe Limited" (Press release). European Commission. March 26, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ "UOKiK – Home". www.uokik.gov.pl. Archived from the original on February 27, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ "Sector inquiry in the banking sector". February 8, 2007. Archived from the original on February 28, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ Jan Strupczewski; Foo Yun Chee (December 17, 2014). "EU agrees deal to cap bank card payment fees". Reuters. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2018 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ SEPA: a busy year is coming to its end and another exciting year lies ahead (Speech). November 25, 2010.

- ^ "Trouw.nl". Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ "Rynek kart czekają zmiany (wersja do druku)" (in Polish). Ekonomia24.pl. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "IKO: rewolucyjny system płatności mobilnej od PKO BP – Banki – WP.PL". Banki. Archived from the original on March 30, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Płatności mobilne w Biedronce – Tech – WP.PL". Tech. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Mobile Payments – Bilet w komórce". Skycash.com. Archived from the original on November 17, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Quinio, Akila (May 21, 2024). "Mastercard and Visa face crackdown by UK watchdog on merchant fees". Financial Times. Retrieved November 7, 2024.

- ^ "Britain seeks to rein in Mastercard and Visa fees on retailers". Reuters. May 21, 2024. Retrieved November 7, 2024.

- ^ Chee, Foo (November 6, 2024). "Exclusive: EU regulators investigate if Visa, Mastercard fees harm retailers, document shows". Reuters. Retrieved November 7, 2024.

- ^ Chee, Foo (June 3, 2025). "EU antitrust regulators escalate Visa, Mastercard probe, documents show". Reuters. Retrieved July 28, 2025.

- ^ a b "Visa finds a passport to the future San Mateo Company bets on 'SMART' cards that will exchange information, not just money Archived October 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine." San Jose Mercury News. Monday August 7, 1995. 1F Business. Retrieved on February 2, 2011. "Visa's headquarters remained in San Francisco until 1985 when it relocated to San Mateo. Then, two years ago, it began consolidating scattered sites throughout San Mateo in nearby Foster City with [...]".

- ^ "Week in review." The Daily Journal. January 3, 2009. Retrieved on February 2, 2011.

- ^ a b Leuty, Ron (September 13, 2012). "Visa moving headquarters from San Francisco to Foster City". San Francisco Business Times. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

[Visa] said Thursday that it is closing its headquarters in San Francisco and moving about 100 employees back to its Foster City campus, effective October 1. [...] The bulk of the company's employees—3,100 of more than 7,700 worldwide... are in Foster City.

- ^ Ladendorf, Kirk (December 11, 2012). "Visa confirms plans for Austin offices". Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ Wells, Arnold (May 14, 2019). "Visa grows tech center in North Austin". Austin Business Journal. Archived from the original on January 4, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c Leuty, Ron (November 6, 2019). "Visa moving global HQ, up to 1,500 employees to Giants' Mission Rock". San Francisco Business Times. American City Business Journals. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Li, Roland (June 7, 2024). "Visa opens huge new S.F. office next to home of Giants, Oracle Park". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 4, 2024.

- ^ "Visa Inc. (V) Stock Major Holders - Yahoo Finance". finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "Synovus Selects Visa's Plus and Interlink as Primary Debit Network Providers" Archived June 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, AllBusiness, April 6, 2004. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ "Apple teams with payment networks to turn iPhone into wallet". San Diego News. Net. September 1, 2014. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Visa Rules and Policy". usa.visa.com. Visa, Inc. Archived from the original on September 17, 2025. Retrieved September 23, 2025.

- ^ Razi, Jonathan; Taylor, Keturah (May 23, 2024). "Let's avoid legal patchwork for credit card surcharging". www.paymentsdive.com. Payments Dive. Archived from the original on May 14, 2025. Retrieved September 23, 2025.

- ^ "A guide to credit card surcharges for businesses". stripe.com. January 22, 2025. Archived from the original on September 16, 2025. Retrieved September 23, 2025.

- ^ "State-by-State Credit Card Surcharge Guidance And Laws". staxpayments.com. Retrieved September 23, 2025.

- ^ "U.S. Merchant Surcharge Q and A" (PDF). usa.visa.com. Visa, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 20, 2025. Retrieved September 23, 2025.

- ^ "Ask Visa". usa.visa.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2004. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ^ "Emboldened, Merchants Expected To Push Cheaper Payments|PaymentsSource". paymentssource.com. August 25, 2010. Archived from the original on January 14, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ^ "Reforms to Payment Card Surcharging.", Reserve Bank of Australia. Archived March 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Visa launches new service to secure online payments" Archived March 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, Retrieved September 10, 2014.

- ^ "Visa Credit Card". Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Visa Canada Interchange Reimbursement Fees" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 18, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Visa Credit Card Canada". Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "New Visa payWave Issuers and Merchants Sign Up for Faster, More Convenient Payments". Archived from the original on January 2, 2008.

- ^ "V PAY – your European debit card". Archived from the original on May 17, 2007.

- ^ "Why do Australians lead the way in contactless payments?". Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ Sarah Clark (February 28, 2017). "Mastercard and Visa expand availability of QR payments". Archived from the original on July 15, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- ^ "ICICI launches 'mVisa' mobile payment service". The Economic Times. October 8, 2015. Archived from the original on July 15, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- ^ Sparkes, Matthew (November 27, 2013). "Visa launch V.me digital wallet service". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022.

- ^ Guntrum, Kryssa; Standish, Jake (February 27, 2015). "Visa to Acquire TrialPay". investor.visa. Archived from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ "Hot Topic: A Brand Evolution." Archived May 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Visa Corporate Press Release, January 2007.

- ^ "20 Fun Facts You Never Knew About VISA". MoneyInc. March 20, 2018. Archived from the original on August 30, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ^ "New Visa Cards". The New York Times. July 22, 1983. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ "Payment Cards Fraud and Merchants". Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ^ "HoloMag Introduced." Archived July 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, SEC.GOV Web Site.

- ^ "American Bank Note Holographics Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2005 Financial Results" (PDF) (Press release). Robbinsville, New Jersey. March 31, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008.

On March 14, 2006, Visa informed the Company ... that it is discontinuing the use of the current version of HoloMag based on what Visa describes as an infrequently occurring technical problem at the point of sale

- ^ "Mastercard, Discover, AmEx and Visa ditching signatures". creditcards.com=April 13, 2018. November 17, 2017. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ "Visa Won't Require Signatures". Bloomberg.com=January 12, 2018. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Visa Sponsors Third Paralympic Hall of Fame Induction Archived July 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, International Paralympic Committee (IPC)

- ^ "Visa Renews Olympic Partnership Through 2032". usa.visa.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ^ Visa Worldwide Partners Archived March 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, International Paralympic Committee (IPC)

- ^ "IPC and Visa extend partnership until 2020". Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ 2015 FIBA Americas Championship - Argentina Archived March 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, FIBA.com, Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ "Newsroom – Visa". corporate.visa.com. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ Visa, NFL Give Credit Where Credit is Due Archived March 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, NYSportsJournalism.com, September 22, 2009

- ^ Visa terminates global Rugby World Cup sponsorship Archived April 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Brand Republic, April 17, 2008

- ^ "caterhamf1.com". Archived from the original on October 14, 2012.

- ^ "SK Gaming announces partnership with VISA – Article – TSN". January 6, 2017. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ "Confederación Argentina de Hockey Homepage". Confederación Argentina de Hockey. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Fryer, Jenna (January 24, 2024). "Visa enters F1 with Red Bull, rebrands AlphaTauri with wordy new team name". AP News. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in most cases, will automatically redirect to a localized version of Visa.com based on the user's location)

- Visa Inc. on OpenSecrets, a website that tracks and publishes data on campaign finance and lobbying

- Business data for Visa:

Visa Inc.

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins as BankAmericard and Formation of Visa Network (1958–1976)