Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Holography

View on Wikipedia

Holography is a technique that allows a wavefront to be recorded and later reconstructed. It is best known as a method of generating three-dimensional images, and has a wide range of other uses, including data storage, microscopy, and interferometry. In principle, it is possible to make a hologram for any type of wave.

A hologram is a recording of an interference pattern that can reproduce a 3D light field using diffraction. In general usage, a hologram is a recording of any type of wavefront in the form of an interference pattern. It can be created by capturing light from a real scene, or it can be generated by a computer, in which case it is known as a computer-generated hologram, which can show virtual objects or scenes. Optical holography needs a laser light to record the light field. The reproduced light field can generate an image that has the depth and parallax of the original scene.[1] A hologram is usually unintelligible when viewed under diffuse ambient light. When suitably lit, the interference pattern diffracts the light into an accurate reproduction of the original light field, and the objects that were in it exhibit visual depth cues such as parallax and perspective that change realistically with the different angles of viewing. That is, the view of the image from different angles shows the subject viewed from similar angles.

A hologram is traditionally generated by overlaying a second wavefront, known as the reference beam, onto a wavefront of interest. This generates an interference pattern, which is then captured on a physical medium. When the recorded interference pattern is later illuminated by the second wavefront, it is diffracted to recreate the original wavefront.[2] The 3D image from a hologram can often be viewed with non-laser light. However, in common practice, major image quality compromises are made to remove the need for laser illumination to view the hologram.

A computer-generated hologram is created by digitally modeling and combining two wavefronts to generate an interference pattern image. This image can then be printed onto a mask or film and illuminated with an appropriate light source to reconstruct the desired wavefront.[2] Alternatively, the interference pattern image can be directly displayed on a dynamic holographic display.[3]

Holographic portraiture often resorts to a non-holographic intermediate imaging procedure, to avoid the dangerous high-powered pulsed lasers which would be needed to optically "freeze" moving subjects as perfectly as the extremely motion-intolerant holographic recording process requires. Early holography required high-power and expensive lasers. Currently, mass-produced low-cost laser diodes, such as those found on DVD recorders and used in other common applications, can be used to make holograms. They have made holography much more accessible to low-budget researchers, artists, and dedicated hobbyists.

Most holograms produced are of static objects, but systems for displaying changing scenes on dynamic holographic displays are now being developed.[4][5]

The word holography comes from the Greek words ὅλος (holos; "whole") and γραφή (graphē; "writing" or "drawing").

History

[edit]The Hungarian-British physicist Dennis Gabor invented holography in 1948 while he was looking for a way to improve image resolution in electron microscopes.[6][7][8] Gabor's work was built on pioneering work in the field of X-ray microscopy by other scientists including Mieczysław Wolfke in 1920 and William Lawrence Bragg in 1939.[9] The formulation of holography was an unexpected result of Gabor's research into improving electron microscopes at the British Thomson-Houston Company (BTH) in Rugby, England, and the company filed a patent in December 1947 (patent GB685286). The technique as originally invented is still used in electron microscopy, where it is known as electron holography. Gabor was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1971 "for his invention and development of the holographic method".[10]

Optical holography did not really advance until the development of the laser in 1960. The development of the laser enabled the first practical optical holograms that recorded 3D objects to be made in 1962 by Yuri Denisyuk in the Soviet Union[11] and by Emmett Leith and Juris Upatnieks at the University of Michigan, US.[12]

Early optical holograms used silver halide photographic emulsions as the recording medium. They were not very efficient as the produced diffraction grating absorbed much of the incident light. Various methods of converting the variation in transmission to a variation in refractive index (known as "bleaching") were developed which enabled much more efficient holograms to be produced.[13][14][15]

A major advance in the field of holography was made by Stephen Benton, who invented a way to create holograms that can be viewed with natural light instead of lasers. These are called rainbow holograms.[8]

Basics of holography

[edit]

Holography is a technique for recording and reconstructing light fields.[16]: Section 1 A light field is generally the result of a light source scattered off objects. Holography can be thought of as somewhat similar to sound recording, whereby a sound field created by vibrating matter like musical instruments or vocal cords, is encoded in such a way that it can be reproduced later, without the presence of the original vibrating matter.[17] However, it is even more similar to Ambisonic sound recording in which any listening angle of a sound field can be reproduced in the reproduction.

Laser

[edit]In laser holography, the hologram is recorded using a source of laser light, which is very pure in its color and orderly in its composition. Various setups may be used, and several types of holograms can be made, but all involve the interaction of light coming from different directions and producing a microscopic interference pattern which a plate, film, or other medium photographically records.

In one common arrangement, the laser beam is split into two, one known as the object beam and the other as the reference beam. The object beam is expanded by passing it through a lens and used to illuminate the subject. The recording medium is located where this light, after being reflected or scattered by the subject, will strike it. The edges of the medium will ultimately serve as a window through which the subject is seen, so its location is chosen with that in mind. The reference beam is expanded and made to shine directly on the medium, where it interacts with the light coming from the subject to create the desired interference pattern.

Like conventional photography, holography requires an appropriate exposure time to correctly affect the recording medium. Unlike conventional photography, during the exposure the light source, the optical elements, the recording medium, and the subject must all remain motionless relative to each other, to within about a quarter of the wavelength of the light, or the interference pattern will be blurred and the hologram spoiled. With living subjects and some unstable materials, that is only possible if a very intense and extremely brief pulse of laser light is used, a hazardous procedure which is rarely done outside of scientific and industrial laboratory settings. Exposures lasting several seconds to several minutes, using a much lower-powered continuously operating laser, are typical.

Apparatus

[edit]A hologram can be made by shining part of the light beam directly into the recording medium, and the other part onto the object in such a way that some of the scattered light falls onto the recording medium. A more flexible arrangement for recording a hologram requires the laser beam to be aimed through a series of elements that change it in different ways. The first element is a beam splitter that divides the beam into two identical beams, each aimed in different directions:

- One beam (known as the 'illumination' or 'object beam') is spread using lenses and directed onto the scene using mirrors. Some of the light scattered (reflected) from the scene then falls onto the recording medium.

- The second beam (known as the 'reference beam') is also spread through the use of lenses, but is directed so that it does not come in contact with the scene, and instead travels directly onto the recording medium.

Several different materials can be used as the recording medium. One of the most common is a film very similar to photographic film (silver halide photographic emulsion), but with much smaller light-reactive grains (preferably with diameters less than 20 nm), making it capable of the much higher resolution that holograms require. A layer of this recording medium (e.g., silver halide) is attached to a transparent substrate, which is commonly glass, but may also be plastic.

Process

[edit]When the two laser beams reach the recording medium, their light waves intersect and interfere with each other. It is this interference pattern that is imprinted on the recording medium. The pattern itself is seemingly random, as it represents the way in which the scene's light interfered with the original light source – but not the original light source itself. The interference pattern can be considered an encoded version of the scene, requiring a particular key – the original light source – in order to view its contents.

This missing key is provided later by shining a laser, identical to the one used to record the hologram, onto the developed film. When this beam illuminates the hologram, it is diffracted by the hologram's surface pattern. This produces a light field identical to the one originally produced by the scene and scattered onto the hologram.

Comparison with photography

[edit]Holography may be better understood via an examination of its differences from ordinary photography:

- A hologram represents a recording of information regarding the light that came from the original scene as scattered in a range of directions rather than from only one direction, as in a photograph. This allows the scene to be viewed from a range of different angles, as if it were still present.

- A photograph can be recorded using normal light sources (sunlight or electric lighting) whereas a laser is required to record a hologram.

- A lens is required in photography to record the image, whereas in holography, the light from the object is scattered directly onto the recording medium.

- A holographic recording requires a second light beam (the reference beam) to be directed onto the recording medium.

- A photograph can be viewed in a wide range of lighting conditions, whereas holograms can only be viewed with very specific forms of illumination.

- When a photograph is cut in half, each piece shows half of the scene. When a hologram is cut in half, the whole scene can still be seen in each piece. This is because, whereas each point in a photograph only represents light scattered from a single point in the scene, each point on a holographic recording includes information about light scattered from every point in the scene. It can be thought of as viewing a street outside a house through a large window, then through a smaller window. One can see all of the same things through the smaller window (by moving the head to change the viewing angle), but the viewer can see more at once through the large window.

- A photographic stereogram is a two-dimensional representation that can produce a three-dimensional effect but only from one point of view, whereas the reproduced viewing range of a hologram adds many more depth perception cues that were present in the original scene. These cues are recognized by the human brain and translated into the same perception of a three-dimensional image as when the original scene might have been viewed.

- A photograph clearly maps out the light field of the original scene. The developed hologram's surface consists of a very fine, seemingly random pattern, which appears to bear no relationship to the scene it recorded.

Physics of holography

[edit]For a better understanding of the process, it is necessary to understand interference and diffraction. Interference occurs when one or more wavefronts are superimposed. Diffraction occurs when a wavefront encounters an object. The process of producing a holographic reconstruction is explained below purely in terms of interference and diffraction. It is somewhat simplified but is accurate enough to give an understanding of how the holographic process works.

For those unfamiliar with these concepts, it is worthwhile to read those articles before reading further in this article.

Plane wavefronts

[edit]A diffraction grating is a structure with a repeating pattern. A simple example is a metal plate with slits cut at regular intervals. A light wave that is incident on a grating is split into several waves; the direction of these diffracted waves is determined by the grating spacing and the wavelength of the light.

A simple hologram can be made by superimposing two plane waves from the same light source on a holographic recording medium. The two waves interfere, giving a straight-line fringe pattern whose intensity varies sinusoidally across the medium. The spacing of the fringe pattern is determined by the angle between the two waves, and by the wavelength of the light.

The recorded light pattern is a diffraction grating. When it is illuminated by only one of the waves used to create it, it can be shown that one of the diffracted waves emerges at the same angle at which the second wave was originally incident, so that the second wave has been 'reconstructed'. Thus, the recorded light pattern is a holographic recording as defined above.

Point sources

[edit]

If the recording medium is illuminated with a point source and a normally incident plane wave, the resulting pattern is a sinusoidal zone plate, which acts as a negative Fresnel lens whose focal length is equal to the separation of the point source and the recording plane.

When a plane wave-front illuminates a negative lens, it is expanded into a wave that appears to diverge from the focal point of the lens. Thus, when the recorded pattern is illuminated with the original plane wave, some of the light is diffracted into a diverging beam equivalent to the original spherical wave; a holographic recording of the point source has been created.

When the plane wave is incident at a non-normal angle at the time of recording, the pattern formed is more complex, but still acts as a negative lens if it is illuminated at the original angle.

Complex objects

[edit]To record a hologram of a complex object, a laser beam is first split into two beams of light. One beam illuminates the object, which then scatters light onto the recording medium. According to diffraction theory, each point in the object acts as a point source of light so the recording medium can be considered to be illuminated by a set of point sources located at varying distances from the medium.

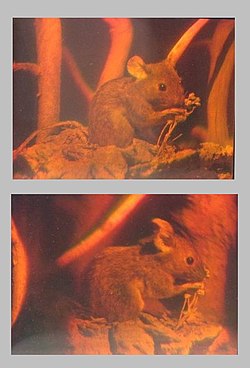

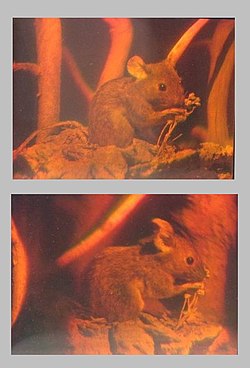

The second (reference) beam illuminates the recording medium directly. Each point source wave interferes with the reference beam, giving rise to its own sinusoidal zone plate in the recording medium. The resulting pattern is the sum of all these 'zone plates', which combine to produce a random (speckle) pattern as in the photograph above.

When the hologram is illuminated by the original reference beam, each of the individual zone plates reconstructs the object wave that produced it, and these individual wavefronts are combined to reconstruct the whole of the object beam. The viewer perceives a wavefront that is identical with the wavefront scattered from the object onto the recording medium, so that it appears that the object is still in place even if it has been removed.

Applications

[edit]Art

[edit]Early on, artists saw the potential of holography as a medium and gained access to science laboratories to create their work. Holographic art is often the result of collaborations between scientists and artists, although some holographers would regard themselves as both an artist and a scientist.

Salvador Dalí claimed to have been the first to employ holography artistically. He was certainly the first and best-known surrealist to do so, but the 1972 New York exhibit of Dalí holograms had been preceded by the holographic art exhibition that was held at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan in 1968 and by the one at the Finch College gallery in New York in 1970, which attracted national media attention.[18] In Great Britain, Margaret Benyon began using holography as an artistic medium in the late 1960s and had a solo exhibition at the University of Nottingham art gallery in 1969.[19] This was followed in 1970 by a solo show at the Lisson Gallery in London, which was billed as the "first London expo of holograms and stereoscopic paintings".[20]

During the 1970s, a number of art studios and schools were established, each with their particular approach to holography. Notably, there was the San Francisco School of Holography established by Lloyd Cross, The Museum of Holography in New York founded by Rosemary (Posy) H. Jackson, the Royal College of Art in London and the Lake Forest College Symposiums organised by Tung Jeong.[21] None of these studios still exist; however, there is the Center for the Holographic Arts in New York[22] and the HOLOcenter in Seoul, which offers artists a place to create and exhibit work.

During the 1980s, many artists who worked with holography helped the diffusion of this so-called "new medium" in the art world, such as Harriet Casdin-Silver of the United States, Dieter Jung of Germany, and Moysés Baumstein of Brazil, each one searching for a proper "language" to use with the three-dimensional work, avoiding the simple holographic reproduction of a sculpture or object. For instance, in Brazil, many concrete poets (Augusto de Campos, Décio Pignatari, Julio Plaza and José Wagner Garcia, associated with Moysés Baumstein) found in holography a way to express themselves and to renew concrete poetry.

A small but active group of artists still integrate holographic elements into their work.[23] Some are associated with novel holographic techniques; for example, artist Matt Brand[24] employed computational mirror design to eliminate image distortion from specular holography.

The MIT Museum[25] and Jonathan Ross[26] both have extensive collections of holography and on-line catalogues of art holograms.

Data storage

[edit]Holographic data storage is a technique that can store information at high density inside crystals or photopolymers. The ability to store large amounts of information in some kind of medium is of great importance, as many electronic products incorporate storage devices. As current storage techniques such as Blu-ray Disc reach the limit of possible data density (due to the diffraction-limited size of the writing beams), holographic storage has the potential to become the next generation of popular storage media. The advantage of this type of data storage is that the volume of the recording media is used instead of just the surface. Currently available SLMs can produce about 1000 different images a second at 1024×1024-bit resolution which would result in about one-gigabit-per-second writing speed.[27]

In 2005, companies such as Optware and Maxell produced a 120 mm disc that uses a holographic layer to store data to a potential 3.9 TB, a format called Holographic Versatile Disc. As of September 2014, no commercial product has been released.

Another company, InPhase Technologies, was developing a competing format, but went bankrupt in 2011 and all its assets were sold to Akonia Holographics, LLC.

While many holographic data storage models have used "page-based" storage, where each recorded hologram holds a large amount of data, more recent research into using submicrometre-sized "microholograms" has resulted in several potential 3D optical data storage solutions. While this approach to data storage can not attain the high data rates of page-based storage, the tolerances, technological hurdles, and cost of producing a commercial product are significantly lower.

Dynamic holography

[edit]In static holography, recording, developing and reconstructing occur sequentially, and a permanent hologram is produced.

There also exist holographic materials that do not need the developing process and can record a hologram in a very short time. This allows one to use holography to perform some simple operations in an all-optical way. Examples of applications of such real-time holograms include phase-conjugate mirrors ("time-reversal" of light), optical cache memories, image processing (pattern recognition of time-varying images), and optical computing.

The amount of processed information can be very high (terabits/s), since the operation is performed in parallel on a whole image. This compensates for the fact that the recording time, which is in the order of a microsecond, is still very long compared to the processing time of an electronic computer. The optical processing performed by a dynamic hologram is also much less flexible than electronic processing. On one side, one has to perform the operation always on the whole image, and on the other side, the operation a hologram can perform is basically either a multiplication or a phase conjugation. In optics, addition and Fourier transform are already easily performed in linear materials, the latter simply by a lens. This enables some applications, such as a device that compares images in an optical way.[28]

The search for novel nonlinear optical materials for dynamic holography is an active area of research. The most common materials are photorefractive crystals, but in semiconductors or semiconductor heterostructures (such as quantum wells), atomic vapors and gases, plasmas and even liquids, it was possible to generate holograms.

A particularly promising application is optical phase conjugation. It allows the removal of the wavefront distortions a light beam receives when passing through an aberrating medium, by sending it back through the same aberrating medium with a conjugated phase. This is useful, for example, in free-space optical communications to compensate for atmospheric turbulence (the phenomenon that gives rise to the twinkling of starlight).

Hobbyist use

[edit]

Since the beginning of holography, many holographers have explored its uses and displayed them to the public.

In 1971, Lloyd Cross opened the San Francisco School of Holography and taught amateurs how to make holograms using only a small (typically 5 mW) helium-neon laser and inexpensive home-made equipment. Holography had been supposed to require a very expensive metal optical table set-up to lock all the involved elements down in place and damp any vibrations that could blur the interference fringes and ruin the hologram. Cross's home-brew alternative was a sandbox made of a cinder block retaining wall on a plywood base, supported on stacks of old tires to isolate it from ground vibrations, and filled with sand that had been washed to remove dust. The laser was securely mounted atop the cinder block wall. The mirrors and simple lenses needed for directing, splitting and expanding the laser beam were affixed to short lengths of PVC pipe, which were stuck into the sand at the desired locations. The subject and the photographic plate holder were similarly supported within the sandbox. The holographer turned off the room light, blocked the laser beam near its source using a small relay-controlled shutter, loaded a plate into the holder in the dark, left the room, waited a few minutes to let everything settle, then made the exposure by remotely operating the laser shutter.

In 1979, Jason Sapan opened the Holographic Studios in New York City. Since then, they have been involved in the production of many holographs for many artists as well as companies.[29] Sapan has been described as the "last professional holographer of New York".

Many of these holographers would go on to produce art holograms. In 1983, Fred Unterseher, a co-founder of the San Francisco School of Holography and a well-known holographic artist, published the Holography Handbook, an easy-to-read guide to making holograms at home. This brought in a new wave of holographers and provided simple methods for using the then-available AGFA silver halide recording materials.

In 2000, Frank DeFreitas published the Shoebox Holography Book and introduced the use of inexpensive laser pointers to countless hobbyists. For many years, it had been assumed that certain characteristics of semiconductor laser diodes made them virtually useless for creating holograms, but when they were eventually put to the test of practical experiment, it was found that not only was this untrue, but that some actually provided a coherence length much greater than that of traditional helium-neon gas lasers. This was a very important development for amateurs, as the price of red laser diodes had dropped from hundreds of dollars in the early 1980s to about $5 after they entered the mass market as a component pulled from CD, or later, DVD players from the mid-1980s onwards. Now, there are thousands of amateur holographers worldwide.

By late 2000, holography kits with inexpensive laser pointer diodes entered the mainstream consumer market. These kits enabled students, teachers, and hobbyists to make several kinds of holograms without specialized equipment, and became popular gift items by 2005.[30] The introduction of holography kits with self-developing plates in 2003 made it possible for hobbyists to create holograms without the bother of wet chemical processing.[31]

In 2006, a large number of surplus holography-quality green lasers (Coherent C315) became available and put dichromated gelatin (DCG) holography within the reach of the amateur holographer. The holography community was surprised at the amazing sensitivity of DCG to green light. It had been assumed that this sensitivity would be uselessly slight or non-existent. Jeff Blyth responded with the G307 formulation of DCG to increase the speed and sensitivity to these new lasers.[32]

Kodak and Agfa, the former major suppliers of holography-quality silver halide plates and films, are no longer in the market. While other manufacturers have helped fill the void, many amateurs are now making their own materials. The favorite formulations are dichromated gelatin, Methylene-Blue-sensitised dichromated gelatin, and diffusion method silver halide preparations. Jeff Blyth has published very accurate methods for making these in a small lab or garage.[33]

A small group of amateurs are even constructing their own pulsed lasers to make holograms of living subjects and other unsteady or moving objects.[34]

Holographic interferometry

[edit]Holographic interferometry (HI) is a technique that enables static and dynamic displacements of objects with optically rough surfaces to be measured to optical interferometric precision (i.e. to fractions of a wavelength of light).[35][36] It can also be used to detect optical-path-length variations in transparent media, which enables, for example, fluid flow to be visualized and analyzed. It can also be used to generate contours representing the form of the surface or the isodose regions in radiation dosimetry.[37]

It has been widely used to measure stress, strain, and vibration in engineering structures.

Interferometric microscopy

[edit]The hologram keeps the information on the amplitude and phase of the field. Several holograms may keep information about the same distribution of light, emitted to various directions. The numerical analysis of such holograms allows one to emulate large numerical aperture, which, in turn, enables enhancement of the resolution of optical microscopy. The corresponding technique is called interferometric microscopy. Recent achievements of interferometric microscopy allow one to approach the quarter-wavelength limit of resolution.[38]

Sensors or biosensors

[edit]The hologram is made with a modified material that interacts with certain molecules generating a change in the fringe periodicity or refractive index, therefore, the color of the holographic reflection.[39][40]

Security

[edit]

Holograms are commonly used for security, as they are replicated from a master hologram that requires expensive, specialized and technologically advanced equipment, and are thus difficult to forge. They are used widely in many currencies, such as the Brazilian 20, 50, and 100-reais notes; British 5, 10, 20 and 50-pound notes; South Korean 5000, 10,000, and 50,000-won notes; Japanese 5000 and 10,000 yen notes, Indian 50, 100, 500, and 2000 rupee notes; and all the currently-circulating banknotes of the Canadian dollar, Croatian kuna, Danish krone, and Euro. They can also be found in credit and bank cards as well as passports, ID cards, books, food packaging, DVDs, and sports equipment. Such holograms come in a variety of forms, from adhesive strips that are laminated on packaging for fast-moving consumer goods to holographic tags on electronic products. They often contain textual or pictorial elements to protect identities and separate genuine articles from counterfeits.

Holographic scanners are in use in post offices, larger shipping firms, and automated conveyor systems to determine the three-dimensional size of a package. They are often used in tandem with checkweighers to allow automated pre-packing of given volumes, such as a truck or pallet for bulk shipment of goods. Holograms produced in elastomers can be used as stress-strain reporters due to its elasticity and compressibility, the pressure and force applied are correlated to the reflected wavelength, therefore its color.[41] Holography technique can also be effectively used for radiation dosimetry.[42][43]

High-security registration plates

[edit]High-security holograms can be used on license plates for vehicles such as cars and motorcycles. As of April 2019, holographic license plates are required on vehicles in parts of India to aid in identification and security, especially in cases of car theft. Such number plates hold electronic data of vehicles, and they have a unique ID number and a sticker to indicate authenticity.[44]

Holography using other types of waves

[edit]In principle, it is possible to make a hologram for any wave.

Electron holography is the application of holography techniques to electron waves rather than light waves. Electron holography was invented by Dennis Gabor to improve the resolution and avoid the aberrations of the transmission electron microscope. Today it is commonly used to study electric and magnetic fields in thin films, as magnetic and electric fields can shift the phase of the interfering wave passing through the sample.[45] The principle of electron holography can also be applied to interference lithography.[46]

Acoustic holography enables sound maps of an object to be generated. Measurements of the acoustic field are made at many points close to the object. These measurements are digitally processed to produce the "images" of the object.[47]

Atomic holography has evolved out of the development of the basic elements of atom optics. With the Fresnel diffraction lens and atomic mirrors atomic holography follows a natural step in the development of the physics (and applications) of atomic beams. Recent developments including atomic mirrors and especially ridged mirrors have provided the tools necessary for the creation of atomic holograms,[48] although such holograms have not yet been commercialized.

Neutron beam holography has been used to see the inside of solid objects.[49]

Holograms with x-rays are generated by using synchrotrons or x-ray free-electron lasers as radiation sources and pixelated detectors such as CCDs as recording medium.[50] The reconstruction is then retrieved via computation. Due to the shorter wavelength of x-rays compared to visible light, this approach allows imaging objects with higher spatial resolution.[51] As free-electron lasers can provide ultrashort and x-ray pulses in the range of femtoseconds which are intense and coherent, x-ray holography has been used to capture ultrafast dynamic processes.[52][53][54]

False holograms

[edit]

There are many optical effects that are falsely confused with holography, such as the effects produced by lenticular printing, the Pepper's ghost illusion (or modern variants such as the Musion Eyeliner), tomography and volumetric displays.[55][56] Such illusions have been called "fauxlography".[57][58]

The Pepper's ghost technique, being the easiest to implement of these methods, is most prevalent in 3D displays that claim to be (or are referred to as) "holographic". While the original illusion, used in theater, involved actual physical objects and persons, located offstage, modern variants replace the source object with a digital screen, which displays imagery generated with 3D computer graphics to provide the necessary depth cues. The reflection, which seems to float mid-air, is still flat, however, and thus it is less realistic than if an actual 3D object was being reflected.

Examples of this digital version of Pepper's ghost illusion include the Gorillaz performances in the 2005 MTV Europe Music Awards and the 48th Grammy Awards; and Tupac Shakur's virtual performance at Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in 2012, rapping alongside Snoop Dogg during his set with Dr. Dre.[59] Digital avatars of the Swedish supergroup ABBA were displayed on stage in May 2022.[60] The ABBA performance used technology that was an updated version of Pepper's Ghost created by Industrial Light & Magic.[61] American rock group KISS unveiled similar digital avatars in December 2023 to tour in their place at the conclusion of the End of the Road World Tour using the same Pepper's Ghost technology as the ABBA avatars.[62]

An even simpler illusion can be created by rear-projecting realistic images into semi-transparent screens. The rear projection is necessary because otherwise the semi-transparency of the screen would allow the background to be illuminated by the projection, which would break the illusion.

Crypton Future Media, a music software company that produced Hatsune Miku,[63] one of many Vocaloid singing synthesizer applications, has produced concerts that have Miku, along with other Crypton Vocaloids, performing on stage as "holographic" characters. These concerts use rear projection onto a semi-transparent DILAD screen[64][65] to achieve its "holographic" effect.[66][67]

In 2011, in Beijing, apparel company Burberry produced the "Burberry Prorsum Autumn/Winter 2011 Hologram Runway Show", which included life size 2-D projections of models. The company's own video[68] shows several centered and off-center shots of the main 2-dimensional projection screen, the latter revealing the flatness of the virtual models. The claim that holography was used was reported as fact in the trade media.[69]

In Madrid, on 10 April 2015, a public visual presentation called "Hologramas por la Libertad" (Holograms for Liberty), featuring a ghostly virtual crowd of demonstrators, was used to protest a new Spanish law that prohibits citizens from demonstrating in public places. Although widely called a "hologram protest" in news reports,[70] no actual holography was involved – it was yet another technologically updated variant of the Pepper's ghost illusion.

Holography is distinct from specular holography, which is a technique for making three-dimensional images by controlling the motion of specularities on a two-dimensional surface.[71] It works by reflectively or refractively manipulating bundles of light rays, not by using interference and diffraction.

Tactile holograms

[edit]In fiction

[edit]Holography has been widely referred to in movies, novels, and TV, usually in science fiction, starting in the late 1970s.[72] Science fiction writers absorbed the urban legends surrounding holography that had been spread by overly-enthusiastic scientists and entrepreneurs trying to market the idea.[72] This had the effect of giving the public overly high expectations of the capability of holography, due to the unrealistic depictions of it in most fiction, where they are fully three-dimensional computer projections that are sometimes tactile through the use of force fields.[72] Examples of this type of depiction include the hologram of Princess Leia in Star Wars, Arnold Rimmer from Red Dwarf, who was later converted to "hard light" to make him solid, and the Holodeck and Emergency Medical Hologram from Star Trek.[72]

Holography has served as an inspiration for many video games with science fiction elements. In many titles, fictional holographic technology has been used to reflect real-life misrepresentations of potential military use of holograms, such as the "mirage tanks" in Command & Conquer: Red Alert 2 that can disguise themselves as trees.[73] Player characters are able to use holographic decoys in games such as Halo: Reach and Crysis 2 to confuse and distract the enemy.[73] Starcraft ghost agent Nova has access to "holo decoy" as one of her three primary abilities in Heroes of the Storm.[74]

Fictional depictions of holograms have, however, inspired technological advances in other fields, such as augmented reality, that promise to fulfill the fictional depictions of holograms by other means.[75]

See also

[edit]- 3D file formats

- Computer-generated holography

- Holographic display

- Augmented reality

- Australian Holographics

- Autostereoscopy

- Digital holography

- Digital holographic microscopy

- Digital planar holography

- Fog display

- Holographic principle

- Holonomic brain theory

- Hogel Processing Unit

- Integral imaging

- List of emerging technologies

- Phase-coherent holography

- Plasmon – possible applications (full color holography)

- Tomography

- Volumetric display

- Volumetric printing

References

[edit]- ^ "What is Holography? | holocenter". Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ a b Jesacher, Alexander; Ritsch-Marte, Monika (2 January 2016). "Synthetic holography in microscopy: opportunities arising from advanced wavefront shaping". Contemporary Physics. 57 (1): 46–59. Bibcode:2016ConPh..57...46J. doi:10.1080/00107514.2015.1120007. ISSN 0010-7514.

- ^ Sahin, Erdem; Stoykova, Elena; Mäkinen, Jani; Gotchev, Atanas (20 March 2020). "Computer-Generated Holograms for 3D Imaging: A Survey" (PDF). ACM Computing Surveys. 53 (2): 32:1–32:35. doi:10.1145/3378444. ISSN 0360-0300. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2024.

- ^ Blanche, P.-A.; Bablumian, A.; Voorakaranam, R.; Christenson, C.; Lin, W.; Gu, T.; Flores, D.; Wang, P.; et al. (2010). "Holographic three-dimensional telepresence using large-area photorefractive polymer". Nature. 468 (7320): 80–83. Bibcode:2010Natur.468...80B. doi:10.1038/nature09521. PMID 21048763. S2CID 205222841.

- ^ Smalley, D. E.; Nygaard, E.; Squire, K.; Van Wagoner, J.; Rasmussen, J.; Gneiting, S.; Qaderi, K.; Goodsell, J.; Rogers, W.; Lindsey, M.; Costner, K.; Monk, A.; Pearson, M.; Haymore, B.; Peatross, J. (25 January 2018). "A photophoretic-trap volumetric display". Nature. 553 (7689): 486–490. Bibcode:2018Natur.553..486S. doi:10.1038/nature25176. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 29368704. S2CID 4451867.

- ^ Gabor, Dennis (1948). "A new microscopic principle". Nature. 161 (4098): 777–8. Bibcode:1948Natur.161..777G. doi:10.1038/161777a0. PMID 18860291. S2CID 4121017.

- ^ Gabor, Dennis (1949). "Microscopy by reconstructed wavefronts". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 197 (1051): 454–487. Bibcode:1949RSPSA.197..454G. doi:10.1098/rspa.1949.0075. S2CID 123187722.

- ^ a b Blanche, Pierre-Alexandre (2014). Field guide to holography. SPIE field guides. Bellingham, Wash: SPIE Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8194-9957-8.

- ^ Hariharan, P. (1996). Optical Holography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43348-8.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1971". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Denisyuk, Yuri N. (1962). "On the reflection of optical properties of an object in a wave field of light scattered by it". Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR. 144 (6): 1275–1278.

- ^ Leith, E.N.; Upatnieks, J. (1962). "Reconstructed wavefronts and communication theory". J. Opt. Soc. Am. 52 (10): 1123–1130. Bibcode:1962JOSA...52.1123L. doi:10.1364/JOSA.52.001123.

- ^ Upatnieks, J; Leonard, C (1969). "Diffraction efficiency of bleached, photographically recorded interference patterns". Applied Optics. 8 (1): 85–89. Bibcode:1969ApOpt...8...85U. doi:10.1364/ao.8.000085. PMID 20072177.

- ^ Graube, A (1974). "Advances in bleaching methods for photographically recorded holograms". Applied Optics. 13 (12): 2942–6. Bibcode:1974ApOpt..13.2942G. doi:10.1364/ao.13.002942. PMID 20134813.

- ^ Phillips, N. J.; Porter, D. (1976). "An advance in the processing of holograms". Journal of Physics E: Scientific Instruments. 9 (8): 631. Bibcode:1976JPhE....9..631P. doi:10.1088/0022-3735/9/8/011.

- ^ Hariharan, P (2002). Basics of Holography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-75556-9.

- ^ Richards, Keith L. (2018). Design engineer's sourcebook. Boca Raton. ISBN 978-1-315-35052-3. OCLC 990152205.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The History and Development of Holography". Holophile.com. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Coyle, Rebecca (1990). "Holography – Art in the space of technology". In Hayward, Philip (ed.). Culture, Technology & Creativity in the Late Twentieth Century. London, England: John Libbey and Company. pp. 65–88. ISBN 978-0-86196-266-2.

- ^ "Margaret Benyon Holography". Lisson Gallery. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ Integraf. "Dr. Tung J. Jeong Biography". Integraf.com. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "holocenter". holocenter. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "The Universal Hologram". Cherry Optical Holography.

- ^ Holographic metalwork http://www.zintaglio.com

- ^ "MIT Museum: Collections – Holography". Web.mit.edu. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "The Jonathan Ross Hologram Collection". Jrholocollection.com. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Lang, M.; Eschler, H. (1 October 1974). "Gigabyte capacities for holographic memories". Optics & Laser Technology. 6 (5): 219–224. Bibcode:1974OptLT...6..219L. doi:10.1016/0030-3992(74)90061-9. ISSN 0030-3992.

- ^ R. Ryf et al. High-frame-rate joint Fourier-transform correlator based on Sn2P2S6 crystal, Optics Letters 26, 1666–1668 (2001)

- ^ Strochlic, Nina (27 May 2014). "New York's Hologram King is Also the City's Last Pro Holographer". The Daily Beast.

- ^ Stephen Cass: Holiday Gifts 2005 Gifts and gadgets for technophiles of all ages: Do-It Yourself-3-D. In IEEE Spectrum, November 2005

- ^ Chiaverina, Chris: Litiholo holography – So easy even a caveman could have done it (apparatus review) Archived 8 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. In The Physics Teacher, vol. 48, November 2010, pp. 551–552.

- ^ "A Holography FAQ". HoloWiki. 15 February 2011. Archived from the original on 6 November 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Many methods are here". Holowiki.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Jeff Blyth's Film Formulations". Cabd0.tripod.com. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Powell, RL; Stetson, KA (1965). "Interferometric Vibration Analysis by Wavefront Reconstruction". J. Opt. Soc. Am. 55 (12): 1593–8. Bibcode:1965JOSA...55.1593P. doi:10.1364/josa.55.001593.

- ^ Jones, Robert; Wykes, Catherine (1989). Holographic and Speckle Interferometry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34417-4.

- ^ Beigzadeh, A.M.; Vaziri, M.R. Rashidian; Ziaie, F. (2017). "Modelling of a holographic interferometry based calorimeter for radiation dosimetry". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A. 864: 40–49. Bibcode:2017NIMPA.864...40B. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2017.05.019.

- ^ Y.Kuznetsova; A.Neumann, S.R.Brueck (2007). "Imaging interferometric microscopy–approaching the linear systems limits of optical resolution". Optics Express. 15 (11): 6651–6663. Bibcode:2007OExpr..15.6651K. doi:10.1364/OE.15.006651. PMID 19546975.

- ^ Yetisen, AK; Butt, H; da Cruz Vasconcellos, F; Montelongo, Y; Davidson, CAB; Blyth, J; Carmody, JB; Vignolini, S; Steiner, U; Baumberg, JJ; Wilkinson, TD; Lowe, CR (2013). "Light-Directed Writing of Chemically Tunable Narrow-Band Holographic Sensors". Advanced Optical Materials. 2 (3): 250–254. doi:10.1002/adom.201300375. S2CID 96257175.

- ^ MartíNez-Hurtado, J. L.; Davidson, C. A. B.; Blyth, J.; Lowe, C. R. (2010). "Holographic Detection of Hydrocarbon Gases and Other Volatile Organic Compounds". Langmuir. 26 (19): 15694–15699. doi:10.1021/la102693m. PMID 20836549.

- ^ 'Elastic hologram' pages 113–117, Proc. of the IGC 2010, ISBN 978-0-9566139-1-2 here: http://www.dspace.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/225960

- ^ Beigzadeh, A.M. (2017). "Modelling of a holographic interferometry based calorimeter for radiation dosimetry". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment. 864: 40–49. Bibcode:2017NIMPA.864...40B. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2017.05.019.

- ^ Beigzadeh, A.M. (2018). "Double-exposure holographic interferometry for radiation dosimetry: A new developed model". Radiation Measurements. 119: 132–139. Bibcode:2018RadM..119..132B. doi:10.1016/j.radmeas.2018.10.010. S2CID 105842469.

- ^ "Why has the government made high security registration plates mandatory". The Economic Times. ET Online. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ R. E. Dunin-Borkowski et al., Micros. Res. and Tech. vol. 64, pp. 390–402 (2004)

- ^ Ogai, K.; et al. (1993). "An Approach for Nanolithography Using Electron Holography". Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 32 (12S): 5988–5992. Bibcode:1993JaJAP..32.5988O. doi:10.1143/jjap.32.5988. S2CID 123606284.

- ^ "Acoustic Holography". Bruel and Kjaer. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ F. Shimizu; J.Fujita (March 2002). "Reflection-Type Hologram for Atoms". Physical Review Letters. 88 (12) 123201. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..88l3201S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.123201. PMID 11909457.

- ^ Swenson, Gayle (20 October 2016). "Move Over, Lasers: Scientists Can Now Create Holograms from Neutrons, Too". NIST. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ^ Eisebitt, S.; et al. (2004). "Lensless imaging of magnetic nanostructures by X-ray spectro-holography". Nature. 432 (7019): 885–888. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..885E. doi:10.1038/nature03139. PMID 15602557. S2CID 4423853.

- ^ Pfau, B.; et al. (2014). "Influence of stray fields on the switching-field distribution for bit-patterned media based on pre-patterned substrates" (PDF). Applied Physics Letters. 105 (13): 132407. Bibcode:2014ApPhL.105m2407P. doi:10.1063/1.4896982. S2CID 121512138.

- ^ Chapman, H. N.; et al. (2007). "Femtosecond time-delay X-ray holography" (PDF). Nature. 448 (7154): 676–679. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..676C. doi:10.1038/nature06049. PMID 17687320. S2CID 4406541.

- ^ Günther, C.M.; et al. (2011). "Sequential femtosecond X-ray imaging". Nature Photonics. 5 (2): 99–102. Bibcode:2011NaPho...5...99G. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2010.287.

- ^ von Korff, Schmising; et al. (2014). "Imaging Ultrafast Demagnetization Dynamics after a Spatially Localized Optical Excitation" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 112 (21) 217203. Bibcode:2014PhRvL.112u7203V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.217203. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2023.

- ^ "Holographic announcers at Luton airport". BBC News. 31 January 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Farivar, Cyrus (16 April 2012). "Tupac "hologram" merely pretty cool optical illusion". Ars Technica. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Holographic 3D Technology: From Sci-fi Fantasy to Engineering Reality". International Year of Light Blog. 28 September 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017.

- ^ Gordon, Marcus A. (2017). Habitat 44º (MFA). OCAD University. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.30421.88802.

- ^ Sung, Carolyn; Gauk-Roger, Topher; Quan, Denise; Iavazzi, Jessica (16 April 2012). "Tupac returns as a hologram at Coachella". The Marquee Blog. CNN Blogs. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Brause; Mills (27 May 2022). "Super Trouper: ABBA returns to stage as virtual avatars for London gigs". Reuters. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Carter, Ninian (27 November 2018). "ABBA's mysterious "Abbatars" revealed". Graphic News. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Amorosi, A. D. (3 December 2023). "KISS Says Farewell at Madison Square Garden, Before Passing the Torch to Band's Avatar Successors: Concert Review". Variety. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ "Crypton" クリプトン (in Japanese). Crypton.co.jp. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ G., Adrian. "LA's Anime Expo hosting Hatsune Miku's first US live performance on 2 July". Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ ""We can invite Hatsune Miku in my room!", Part 2 (video)". Youtube.com. 7 September 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Technically incorrect: Tomorrow's Miley Cyrus? A hologram live in concert!". Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ "Hatsune Miku – World is Mine Live in HD". YouTube. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ "Burberry Beijing – Full Show". Youtube.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Burberry lands in China". Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ "First Hologram Protest in History Held Against Spain's Gag Law". revolution-news.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ "specular holography: how". Zintaglio.com. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d Johnston, Sean (2006). "The Hologram and Popular Culture". Holographic Visions: a History of New Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press, UK. pp. 405–408. ISBN 978-0-19-151388-6. OCLC 437109030.

- ^ a b Johnston, Sean F. (2015). "11 - Channeling Dreams". Holograms: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-102138-1.

- ^ "Nova - Heroes of the Storm". us.battle.net. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ Richardson, Martin (13 November 2017). The Hologram: Principles and Techniques. Wiltshire, John D. Hoboken, NJ. ISBN 978-1-119-08890-5. OCLC 1000385946.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Bibliography

[edit]- Hariharan P, 1996, Optical Holography, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43965-5

- Hariharan P, 2002, Basics of Holography, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-00200-1

- Lipson A., Lipson SG, Lipson H, Optical Physics, 2011, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-49345-1

Further reading

[edit]- Lasers and holography: an introduction to coherent optics W. E. Kock, Dover Publications (1981), ISBN 978-0-486-24041-1

- Principles of holography H. M. Smith, Wiley (1976), ISBN 978-0-471-80341-6

- G. Berger et al., Digital Data Storage in a phase-encoded holographic memory system: data quality and security, Proceedings of SPIE, Vol. 4988, pp. 104–111 (2003)

- Holographic Visions: A History of New Science Sean F. Johnston, Oxford University Press (2006), ISBN 0-19-857122-4

- Saxby, Graham (2003). Practical Holography, Third Edition. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-0-7503-0912-7.

- Three-Dimensional Imaging Techniques Takanori Okoshi, Atara Press (2011), ISBN 978-0-9822251-4-1

- Holographic Microscopy of Phase Microscopic Objects: Theory and Practice Tatyana Tishko, Tishko Dmitry, Titar Vladimir, World Scientific (2010), ISBN 978-981-4289-54-2

- Richardson, Martin J.; Wiltshire, John D. (2017). Richardson, Martin J.; Wiltshire, John D. (eds.). The Hologram: Principles and Techniques. Wiley. Bibcode:2017hpt..book.....R. doi:10.1002/9781119088929. ISBN 978-1-119-08890-5. OCLC 1000385946.

External links

[edit]- "Dennis Gabor – Autobiography", 30 September 2004, Nobelprize.org

- "Holography, 1948-1971 Nobel Lecture", 11 December 1971, by Dennis Gabor

- "How Holograms Work", How Stuff Works, by Tracy V. Wilson, 30 August 2023

- "Making Real Holograms!!!!!!" at YouTube by The Thought Emporium, 19 November 2020

- "How are holograms possible?" at YouTube by Grant Sanderson, 3Blue1Brown, 5 October 2024

Holography

View on GrokipediaHistory

Invention and Early Concepts

Holography was invented by Hungarian-British physicist Dennis Gabor in 1948 as a method to enhance the resolution of electron microscopes by reconstructing the full wavefront of scattered electrons, addressing the limitations of conventional imaging that captured only intensity rather than phase information.[5][6] Gabor, working at the British Thomson-Houston Company, proposed this technique in his seminal paper "A New Microscopic Principle," where he described holography—derived from the Greek words holos (whole) and graphein (to write)—as a two-step process of recording an interference pattern and reconstructing the original wavefront to achieve superior detail in microscopic images.[7] For this groundbreaking contribution, Gabor was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1971, recognizing the holographic method's potential despite its initial experimental constraints.[5] Gabor's early experiments demonstrated the principle through optical analogs, as direct electron holography proved challenging; he used filtered mercury arc lamps to achieve partial coherence, illuminating simple test objects like pins or gratings to record inline holograms on photographic plates.[2] These inline setups involved the object placed directly in the path of the reference beam, producing an interference pattern that encoded both amplitude and phase, which was then reconstructed by re-illuminating the plate to project a virtual image. However, the incoherent nature of the light sources resulted in blurred recordings, with coherence lengths limited to mere millimeters, restricting the holograms to small-scale objects and low-resolution reconstructions often applied to simulate electron micrograph corrections.[9] In the 1950s, theoretical foundations were further explored by collaborators like Gordon Rogers at Associated Electrical Industries (AEI), who investigated optical implementations of wavefront reconstruction to bypass electron microscopy hurdles, critiquing and refining Gabor's formulations for practical imaging applications.[10] Rogers' work emphasized the method's versatility beyond electrons, proposing adaptations for light-based systems while grappling with coherence issues.[11] Key challenges in these pre-laser efforts included the twin-image problem, where the reconstructed real image overlapped with an out-of-focus conjugate twin due to the inline geometry, and overall low resolution from partial spatial and temporal coherence, which smeared fine details and reduced contrast.[12] These limitations persisted until the invention of the laser provided the necessary coherent illumination to enable high-fidelity holograms.[9]Development with Coherent Light

The invention of the laser by Theodore Maiman in 1960 provided the coherent light source essential for practical holography, enabling high-resolution interference patterns that mercury arc lamps could not achieve.[13] Maiman's ruby laser, first demonstrated on May 16, 1960, at Hughes Research Laboratories, produced a narrow beam of monochromatic light, marking a breakthrough in optical technology.[14] Emmett Leith and Juris Upatnieks at the University of Michigan quickly adopted this new coherent source, applying it in 1962 to develop off-axis holography, which addressed the twin-image problem inherent in Dennis Gabor's earlier inline method. In their seminal work, they introduced a reference beam at an angle to the object beam, spatially separating the real image, virtual image, and zero-order term during reconstruction, thus allowing clear viewing of three-dimensional scenes without overlap.[15] This off-axis geometry, detailed in their 1962 paper, transformed holography from a theoretical concept into a viable imaging technique using helium-neon lasers. Independently, in 1962, Yuri Denisyuk at the Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute in Leningrad developed reflection holography using a single-beam setup, where the reference and object beams shared the same path but were separated by the recording medium.[16] Denisyuk's method recorded volume holograms that could reconstruct full-color three-dimensional images viewable in white light, leveraging the laser's coherence to produce fine interference fringes throughout the emulsion thickness.[17] This approach enabled vibrant, lifelike holograms of objects, distinguishing it from transmission holograms by allowing illumination from the viewer side.[16] A landmark demonstration occurred in 1964 at the Optical Society of America meeting, where Leith and Upatnieks presented a transmission hologram of a toy train, recorded using their off-axis technique with a helium-neon laser.[18] This hologram, capturing the train's three-dimensional structure with remarkable clarity, astonished attendees and solidified holography's status as a distinct field of optics.[19] The shift from inline to off-axis recording geometries, facilitated by coherent light, not only resolved image separation issues but also paved the way for broader applications in visualization and data storage.[15]Post-1960s Evolution and Recent Advances

In the 1970s, holography transitioned from laboratory experiments to early commercialization, particularly in aerospace and artistic applications. McDonnell Douglas Electronics Company, after acquiring Conductron Corporation in 1971, established a dedicated pulsed-laser holography laboratory to develop techniques for nondestructive testing and flow visualization in aerospace engineering, such as detecting density gradients in subsonic airflow around airfoils.[20][21] However, the lab closed in 1973 due to limited market demand from advertising and corporate sectors, marking an early challenge in scaling the technology.[22] Concurrently, artists like Salvador Dalí embraced holography as a medium for multidimensional expression, collaborating with Selwyn Lissack from 1971 to 1976 to create seven laser-based holograms, including Alice Cooper's Brain (1973) and Dali Painting Gala (1976), which explored 3D and 4D concepts despite playback limitations from bulky laser systems.[23] The 1980s and 1990s saw holography expand into consumer security products, driven by its anti-counterfeiting potential. In 1981, the International Banknote Company secured exclusive rights to key hologram patents from Emmett Leith and Juris Upatnieks, leading to the development of holographic images for credit cards.[24] Mastercard introduced holograms on its cards in 1983, followed by Visa that same year, resulting in an 8% reduction in counterfeits in 1984 compared to 1983 and 58% by mid-1986 compared to mid-1985, with non-hologram cards phased out by July 1986.[24] This growth extended to other consumer goods, with holographic sales exceeding $15 million in 1987 for product differentiation and authentication.[25] Efforts in data storage, such as the Holographic Versatile Disc (HVD) project initiated in 2004 by the Holography System Development Forum—including companies like Hitachi and Optware—aimed for 3.9 TB capacity per 12 cm disc with transfer speeds over 1 Gbit/s, but the initiative failed to commercialize due to funding shortages, culminating in the 2010 bankruptcy of key developer InPhase Technologies.[26][27] Recent advances from 2024 to 2025 have integrated holography with optoelectronics, AI, and computational methods, enhancing accessibility for consumer and biomedical uses. Researchers at the University of St Andrews developed a compact optoelectronic device combining organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) with metasurfaces in August 2025, enabling holographic projections from smartphones without bulky components and paving the way for everyday 3D displays in communication and gaming.[28] AI-driven computer-generated holography progressed with real-time systems, such as a February 2025 real-time holographic camera enabling high-fidelity 3D scene hologram generation at video rates using deep learning (FS-Net)[29] and an August 2025 full-color video holography pipeline achieving FHD (1080p) at over 260 FPS using a Mamba-Unet architecture (HoloMamba).[30] In biomedical applications, single-pixel digital holography advanced with a September 2024 multi-head attention network for phase-shifting incoherent imaging, allowing label-free 3D visualization of cells and tissues, and an August 2025 ultrahigh-throughput system for complex-field microscopy beyond visible light.[31][32] The 2024 Optica Digital Holography and Three-Dimensional Imaging meeting in Paestum, Italy, underscored these trends, featuring sessions on polarization holography for enhanced contrast in quantitative phase imaging and extensions to non-visible wavelengths, such as infrared and terahertz for biomedical and scattering media applications.[33][34]Fundamental Principles

Wave Interference and Diffraction Basics

Wave interference occurs when two or more coherent waves superpose, resulting in regions of constructive interference where amplitudes add to produce brighter intensity and destructive interference where they cancel to produce darker regions.[35] This phenomenon is vividly demonstrated in Young's double-slit experiment, conducted by Thomas Young in 1801, where monochromatic light passes through two closely spaced slits, creating an alternating pattern of bright and dark fringes on a distant screen due to the phase-dependent superposition of waves from each slit.[35] The spacing of these fringes allows measurement of the light's wavelength, confirming its wave nature.[35] Diffraction refers to the bending of waves around obstacles or through apertures, leading to spreading and pattern formation that deviates from geometric optics predictions.[36] This behavior is explained by the Huygens-Fresnel principle, which posits that every point on a wavefront acts as a source of secondary spherical wavelets, with the new wavefront formed by the envelope of these wavelets, modulated by an obliquity factor to account for forward propagation preference.[36] In diffraction, interference among these secondary waves produces characteristic patterns, such as the central bright spot and surrounding rings in single-slit diffraction.[36] For stable interference and diffraction patterns to form, light must exhibit sufficient coherence, which quantifies the predictability of phase relationships between waves.[37] Temporal coherence requires a narrow spectral bandwidth, as in monochromatic sources, ensuring waves maintain fixed phase differences over the path lengths involved, typically measured by coherence length , where is coherence time and is refractive index.[37] Spatial coherence demands uniformity across the beam's transverse extent, as achieved in laser light, allowing consistent phase correlations over the aperture size to produce clear fringes without blurring.[37] The intensity resulting from two-beam interference is given by the equation where and are the individual intensities, and is the phase difference between the waves, leading to maximum intensity for and minimum for .[38] This formula underpins the contrast in interference patterns observed in holography.[38]Hologram Recording and Reconstruction

The recording of a hologram begins with the illumination of the subject by a coherent object beam, typically derived from a laser source, which scatters light to form a complex wavefront containing both amplitude and phase information about the object. This object beam is then superimposed with a reference beam, a coherent plane or spherical wave from the same laser, at a photosensitive recording medium such as a silver halide emulsion.[39] The interference between the object beam and reference beam produces an intensity pattern , which is captured by the medium as a spatial variation in transmittance or density that encodes the phase differences essential for three-dimensional reconstruction. This process, pioneered in off-axis configurations to separate reconstructed orders, requires high coherence to maintain fringe visibility over the exposure time, typically on the order of seconds to minutes depending on the medium's sensitivity. Reconstruction occurs when the developed hologram is illuminated by a beam matching the original reference wave, causing diffraction of the incident light through the recorded interference pattern to regenerate the original object wavefront.[39] The diffracted field in the primary (virtual) image order approximates the original object field, given by , where is the hologram transmittance proportional to , and denotes convolution accounting for the diffractive propagation; this yields a virtual image appearing behind the plate at the original object position. A conjugate (real) image may also form in front of the plate, though off-axis geometries minimize overlap with the undiffracted beam. The full wavefront reconstruction preserves all optical paths, enabling viewers to perceive depth through natural accommodation and motion parallax as they shift position. Holograms are classified into transmission and reflection types based on beam geometry and viewing requirements. Transmission holograms, such as those developed by Leith and Upatnieks, record the object and reference beams incident on the same side of the medium, requiring coherent laser illumination from the front for reconstruction and producing bright, monochromatic images with full parallax. In contrast, reflection holograms, invented by Yuri Denisyuk in 1962 using a single-beam setup where the reference beam passes through the emulsion to illuminate the object from behind, record fringes parallel to the surface, allowing viewing with white light due to Bragg selectivity that reflects specific wavelengths while transmitting others. The Denisyuk configuration simplifies apparatus by aligning the object directly behind the plate, enabling volume holograms viewable under ordinary illumination without lasers, though with reduced brightness compared to transmission types.[40] The reconstructed wavefront in holography provides complete spatial information, supporting horizontal and vertical parallax—changes in perspective with head movement—as well as depth cues like accommodation, where the eye focuses at varying distances within the image volume, mimicking real scenes up to depths of several centimeters in typical setups.[41] This fidelity arises from the interference pattern's encoding of all light rays diverging from the object, allowing multiple observers to experience true three-dimensionality without eyewear.[42]Differences from Conventional Imaging

Conventional photography records only the intensity of light, which is the square of the light wave's amplitude, thereby losing all phase information and producing a two-dimensional projection of the scene.[43] In contrast, holography captures both the amplitude and phase of the light wavefront through interference patterns between object and reference beams, enabling the reconstruction of the full three-dimensional wavefront.[44] This preservation of phase allows holograms to recreate the original light field, including depth and directional information absent in photographic images.[45] Unlike photography, which relies on lenses to focus light rays using geometric optics, holography operates without lenses, forming images solely through diffraction of the recorded interference pattern.[43] This diffraction-based reconstruction provides true horizontal and vertical parallax, allowing viewers to see different perspectives of the scene by moving their heads, as well as accurate accommodation cues for focusing on objects at various depths.[46] Such cues are not present in conventional stereograms or lenticular prints, which simulate depth through discrete viewpoints but fail to deliver continuous wavefront reconstruction and proper focus responses.[47] Holograms exhibit significantly higher information density than photographs due to the need to resolve fine interference fringes across the entire wavefront.[43] This enables holography to store vastly more data in a similar area, supporting the encoding of complex three-dimensional scenes with high fidelity.[44] A key demonstration of holography's unique distributed storage is that dividing a hologram into pieces still reconstructs the full image from each fragment, albeit dimmer and with a narrower viewing angle, whereas cutting a photographic negative destroys portions of the image irreversibly.[43] This redundancy arises because the interference pattern encodes the entire scene redundantly across the recording medium, unlike the localized pixel mapping in photography.[45]Physics of Holography

Plane Wavefront Propagation

Plane waves form the foundational model for deriving the mathematical principles of holography, as they propagate without divergence and maintain uniform phase across infinite wavefronts perpendicular to their direction of travel. This property makes them ideal for reference beams in holographic recording, enabling clean interference patterns that capture the essential wave interactions. Mathematically, a monochromatic plane wave propagating along the z-direction is expressed aswhere is the constant amplitude, is the wave number with wavelength , is the angular frequency, is the position along the propagation axis, and is time.[48] This representation assumes a linearly polarized wave in free space, satisfying the wave equation and Helmholtz equation under paraxial approximations common in optical holography. The core of holographic recording involves the interference of two such plane waves: typically, a reference plane wave and an object plane wave (as a simplified model for uniform illumination). When these waves intersect at an angle between their propagation directions, they produce a stationary interference pattern of parallel fringes on the recording plane. The spatial period, or fringe spacing , of this pattern is given by

where is the full angle between the beams and is the wavelength.[49] This formula arises from the beat pattern formed by the wave vectors, with the fringe orientation bisecting the angle between the beams; finer spacing occurs at larger , increasing the spatial frequency of the recorded modulation up to the resolution limit of the medium (typically ~5000 lines/mm for silver halide emulsions). The intensity distribution of the fringes is , modulating the medium's transmittance or refractive index proportionally to the exposure.[50] In the reconstruction phase, the developed hologram is illuminated by the original reference plane wave, which diffracts through the fringe grating to regenerate the object wave. Analogous to a one-dimensional diffraction grating, the hologram separates the incident light into discrete orders: the transmitted zeroth order () propagates as the undiffracted reference wave, while the order reconstructs the virtual object wave in its original direction, and produces a real conjugate image. The angles of these diffracted orders follow the grating equation

where is the angle of the reconstructing reference wave (ideally matching the recording), is the m-th order angle relative to the normal, is the order integer, and is the fringe spacing.[50] For reflected holograms (volume gratings), the orders involve internal reflections, with coupling governed by Bragg condition , where is the Bragg angle, selectively enhancing the desired reconstruction while suppressing others. This grating behavior ensures faithful wavefront regeneration, with efficiency depending on modulation depth and wavelength matching; mismatches introduce aberrations or order overlap.[49] Although ideal plane waves provide a clean theoretical framework, real holographic systems approximate them using collimated laser beams, which inevitably include slight curvature and finite coherence lengths. These imperfections prevent perfect planar wavefronts, resulting in granular speckle patterns during reconstruction due to random phase variations across the beam. Speckle manifests as intensity fluctuations in the image, reducing contrast and resolution, with noise variance proportional to the square root of the mean intensity in coherent illumination.[51] Mitigation requires high-coherence sources like He-Ne lasers but highlights the idealized nature of the plane wave model in practical off-axis holography.[51]

Point Source Holography

Point source holography extends the principles of wavefront recording to spherical waves emanating from a localized emitter, providing a foundational model for understanding three-dimensional image reconstruction in simpler configurations. Unlike plane waves, which approximate distant sources with uniform phase fronts, a point source generates a diverging spherical wavefront described by the electric field , where is the amplitude, is the radial distance from the source, is the wavenumber, and is the angular frequency.[52] This form captures the amplitude decay and quadratic phase progression, essential for modeling light from discrete object points in early holographic experiments.[52] When recording a hologram of a single point source, the object wave interferes with a reference wave on the recording medium, producing an intensity pattern dominated by conical fringes. These fringes arise from the superposition of the spherical object wave and a coherent reference, forming hyperboloidal or conical loci of constant phase difference that encode the source's position.[52] Upon reconstruction with a suitable illuminating wave, such as the conjugate reference, the diffracted light focuses to recreate a sharp, three-dimensional image at the original point location, demonstrating the hologram's ability to store and retrieve both amplitude and phase information without lenses.[52] This focused reconstruction highlights holography's superiority over shadowgraphy for depth-resolved imaging of isolated points.[7] The phase difference in the interference between the object wave from the point source and the reference wave is given by , where is the distance from the object point to the recording plane and is the distance from the reference source to the same point on the plane.[52] This path-length-dependent phase shift enables the encoding of axial depth information directly into the fringe spacing, with closer fringes corresponding to greater depth variations. In practice, this relation underpins the paraxial approximation for small angles, ensuring accurate wavefront curvature reproduction during playback.[52] Applications of point source holography to simple scenes, such as pinhole holograms, illustrate practical implementations where a pinhole acts as the point emitter to test system performance. These setups reveal magnification effects proportional to the ratio of reconstruction to recording distances, allowing scaled 3D views of the pinhole's position, while introducing aberrations like spherical distortion if the reference curvature mismatches the object wave.[53] Such demonstrations, common in educational and validation contexts, underscore the technique's role in verifying holographic fidelity without complex objects, though aberrations can blur the image if not compensated by matched spherical references.[53]Handling Complex Scenes

In holography, the wave from a complex, diffuse object—such as a real-world surface with irregular scattering—arises from the superposition of numerous scattered spherical waves emanating from individual surface elements. Each element acts as a secondary point source, contributing a component modulated by the local reflectivity and phase shifts due to path differences and material properties. This collective scattering leads to speckle noise, a random intensity fluctuation pattern resulting from the constructive and destructive interference of these incoherent-like wavelets, which degrades image quality by introducing granularity.[15] The object wave can be approximated as where represents the reflectivity at surface position , and accounts for the phase, integrating over the object's surface to model the diffuse field.[15] Recording holograms of such scenes demands specialized media capable of handling the intensity ratio between the reference and object beams, typically 5:1 to 10:1 for diffuse objects to balance diffraction efficiency and noise. Conventional photographic films fall short, necessitating ultra-fine-grained emulsions with grain sizes around 35 nm and low sensitivity (effective ASA ~0.001), which often require exposure times exceeding 10 seconds to capture the faint scattered light without saturation.[15] Furthermore, an off-axis reference beam geometry is critical, with the beam angled at 45°–60° to spatially separate the reconstructed virtual image, conjugate (twin) image, and undiffracted zero-order beam, thereby minimizing overlap and intermodulation artifacts like halo noise from object self-interference. This configuration, pioneered in early off-axis holography, ensures the true image emerges undistorted for viewing. Upon reconstruction, persistent speckle artifacts appear as noise in the replayed image, but their visibility can be mitigated through temporal averaging over multiple exposures—such as by subtly vibrating the object or diffuser during recording—or spatial filtering of the reconstructed beam to smooth the granular structure. These methods reduce speckle contrast by statistically averaging the random phase variations, improving perceived resolution without altering the underlying wavefront.[54] To theoretically model and predict holograms from complex scenes, computational approaches decompose the object wave into its Fourier components for efficient propagation simulation, avoiding direct integration of myriad spherical wavelets. Fourier transform holography exemplifies this efficiency, where the hologram is the Fourier transform of the object-reference interference, enabling rapid calculation of diffraction patterns for extended, scattering objects via fast algorithms. This framework scales well for diffuse surfaces by leveraging the convolution theorem, transforming spatial-domain scattering into multiplicative frequency-domain operations.[55]Techniques and Methods

Laser Sources and Coherence Requirements