Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

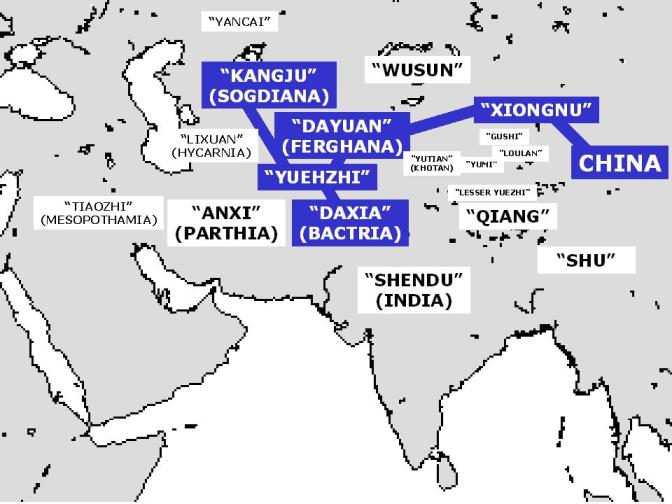

Yancai

View on Wikipedia

Yancai (Chinese: 奄蔡; pinyin: Yǎncài; Wade–Giles: Yen-ts’ai; lit. 'Vast Steppe' < LHC *ʔɨamA-sɑC < OC (125 BCE) *ʔɨam-sɑs, a.k.a. 闔蘇 Hésū < *ĥa̱p-sa̱ĥ; compare also Latin Abzoae[1][2][3][4][5]) was the Chinese name of an ancient nomadic state centered near the Aral Sea during the Han dynasty period (206 BC—220 AD). They are generally considered to have been an Iranian people of the Sarmatian group. After becoming vassals of the Kangju in the 1st century BC, Yancai became known as Alan (Chinese: 阿蘭; pinyin: Ālán; Wade–Giles: A-lan). Yancai 奄蔡 is often connected to the Aorsi of Roman records,[6] while 阿蘭 Alan has been connected to the later Alans.[a]

History

[edit]Yancai is first mentioned in Chapter 123 of the Shiji (whose author, Sima Qian, died c. 90 BC), based on the travels of 2nd century BC Chinese diplomat Zhang Qian:

Yancai lies some 2,000 li [832 km][10] northwest of Kangju. The people are nomads and their customs are generally similar to those of the people of Kangju. The country has over 100,000 archer warriors, and borders on a great shoreless lake.[11]

The people of Yancai are usually considered an Iranian people of the Sarmatian group.[12] They are often connected to the Aorsi of Roman records, who dominated the area between the Don and the Aral Sea and were both a wealthy mercantile people and a powerful military force.[12][13] According to Chinese sources, Yancai belonged to the northern part of the Silk Route, known as the Northern Route.[12] The Chinese sent embassies to Yancai and actively promoted trading relations.[12]

The Later Han dynasty Chinese chronicle, the Hou Hanshu, 88 (covering the period 25–220 and completed in the 5th century), mentioned a report that Yancai was now as vassal state of the Kangju known as Alanliao:

The kingdom of Yancai [lit. ‘Vast Steppe’] has changed its name to the kingdoms of Alan [and] Liao. They occupy the country and the towns. They are dependencies of Kangju [the Talas basin, Tashkent and Sogdiana]. The climate is mild. Wax trees, pines, and ‘white grass’ [aconite] are plentiful. Their way of life and dress are similar to those of Kangju.[14]

Y. A. Zadneprovskiy writes that the subjection of Yancai by the Kangju occurred in the 1st century BC.[12] The westward expansion of the Kangju obliged many of the Sarmatians to migrate westwards, and this contributed significantly to the Migration Period in Europe, which played a major role in world history.[15] The name Alanliao has been connected by modern scholars with that of the Alans.[12]

Yancai is last mentioned in the 3rd century Weilüe:

Then there is the kingdom of Liu, the kingdom of Yan [to the north of Yancai], and the kingdom of Yancai [between the Black and Caspian Seas], which is also called Alan. They all have the same way of life as those of Kangju. To the west, they border Da Qin [Roman territory], to the southeast they border Kangju [the Chu, Talas, and middle Jaxartes basins]. These kingdoms have large numbers of their famous sables. They raise cattle and move about in search of water and fodder. They are close to a large shoreless lake. Previously they were vassals of Kangju [the Chu, Talas, and middle Jaxartes basins]. Now they are no longer vassals.[16][17]

In the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, the Alans emerged as the dominant people of the Sarmatians either through conquering or absorbing other tribes.[13] At this time they migrated westwards to Southern Russia and frequently raided the Parthian and Roman Empire.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Schuessler, Axel (2014). "Phonological Notes on Hàn Period Transcriptions of Foreign Names and Words" (PDF) Archived 2019-07-14 at the Wayback Machine. Studies in Chinese and Sino-Tibetan Linguistics: Dialect, Phonology, Transcription and Text. Language and Linguistics Monograph Series. Taipei, Taiwan: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica (53). p. 268

- ^ Hanshu, commentated by Yan Shigu, vol. 70 text: "師古曰:「胡廣云康居北可一千里有國名奄蔡,一名闔蘇。然則闔蘇即奄蔡也。」"

- ^ Yu, Taishan (July 1998). "A Study of Saka History" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers (80).

Yan Shigu's 顏師古 commentary says: "Hu Guang 胡廣 adds: "Some 1,000 li to the north of Kangju was a state named Yancai, which also was named Hesu. Hence Hesu was identical with Yancai." This shows that the Yancai were also called the Hesu in the Han times.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History IV page 365

- ^ Hulsewé. A. F .P. (1979) China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC - AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. p. 129, n. 316. cited in John E. Hill. Translator's Notes 25.3 & 25.4 to draft translation of Yu Huan's Weilüe. quote: "Chavannes (1905), p. 558, note 5, approves of the identification of Yen-ts’ai with the ‘Αορσοι mentioned by Strabo, as proposed by Hirth (1885), p. 139, note 1 ; he believes this identification to be strengthened by the later name Alan, which explains Ptolemy’s “Alanorsi”. Marquart (1905), pp. 240-241, did not accept this identification, but Pulleyblank (1963), pp. 99 and 220, does, referring for additional support to HSPC 70.6b where the name Ho-su 闔蘇, reconstructed in ‘Old Chinese’ as ĥa̱p-sa̱ĥ, can be compared with Abzoae found in Pliny VI, 38 (see also Pulleyblank (1968), p. 252). Also Humbach (1969), pp. 39-40, accepts the identification, though with some reserve."

- ^ Yu Huan, Weilüe. draft translation by John E. Hill (2004). Translator's Notes 11.2 quote: "Yăncài, already mentioned in the text as a country northwest of Kāngjū (at that time in the region of Tashkend), has long been identified with the Aorsoi of western sources, a nomadic people out of whom the well-known Alans later emerged (Pulleyblank [1962: 99, 220; 1968:252])".

- ^ Weilüe: "Western Regions", quoted in Sanguozhi vol. 30

- ^ Houhanshu, Vol. 88: Xiyu zhuan Yancai" quote: "奄蔡國,改名阿兰聊國,居地城,屬康居。土气温和,多桢松、白草。民俗衣服與康居同。"

- ^ Hill, John E. (translator). The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu: The Xiyu juan “Chapter on the Western Regions” from Hou Hanshu 88 2nd Ed "Section 19 – The Kingdom of Alanliao 阿蘭聊 (the Alans)"

- ^ The Chinese li of the Han period differs from the modern SI base unit of length; one li was equivalent to 415.8 metres.

- ^ Perhaps what is known in the sources as the Northern Sea". The "Great Shoreless lake" probably referred to both the Aral and Caspian seas. Source in Watson, Burton trans. 1993. Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian. Han Dynasty II. (Revised Edition), p. 234. Columbia University Press. New York. ISBN 0-231-08166-9; ISBN 0-231-08167-7 (pbk.)

- ^ a b c d e f Zadneprovskiy 1994, pp. 465–467

- ^ a b Brzezinski & Mielczarek 2002, pp. 7–8

- ^ Hill, John E. 2015. Through the Jade Gate - China to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. 2nd Edition. Volume I, p. 33.

- ^ Zadneprovskiy 1994, pp. 464–465

- ^ For an earlier version of this translation

- ^ Weilüe: "Western Regions", quoted in Sanguozhi vol. 30. quote: "又有柳國,又有岩國,又有奄蔡國一名阿蘭,皆與康居同俗。西與大秦東南與康居接。其國多名貂,畜牧逐水草,臨大澤,故時羈屬康居,今不屬也。"

Sources

[edit]- Brzezinski, Richard; Mielczarek, Mariusz (2002). The Sarmatians, 600 BC-AD 450. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 184176485X. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- Zadneprovskiy, Y. A. (1 January 1994). "The Nomads of Northern Central Asia After The Invasion of Alexander". In Harmatta, János (ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A. D. 250. UNESCO. pp. 457–472. ISBN 9231028464. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- Hill, John E. 2015. Through the Jade Gate - China to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. 2nd Edition. Volume I. CreateSpace. Charleston, S.C.