Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Iazyges

View on Wikipedia

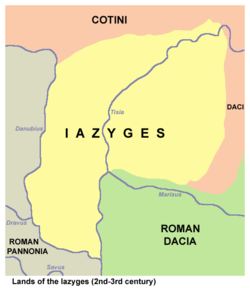

The Iazyges (/aɪˈæzɪdʒiːz/)[a] were an ancient Sarmatian tribe that traveled westward in c. 200 BC from Central Asia to the steppes of modern Ukraine. In c. 44 BC, they moved into modern-day Hungary and Serbia near the Pannonian steppe between the Danube and Tisza rivers, where they adopted a semi-sedentary lifestyle.

In their early relationship with Rome, the Iazyges were used as a buffer state between the Romans and the Dacians; this relationship later developed into one of overlord and client state, with the Iazyges being nominally sovereign subjects of Rome. Throughout this relationship, the Iazyges carried out raids on Roman land, which often caused punitive expeditions to be made against them.

Almost all of the major events of the Iazyges, such as the two Dacian Wars—in both of which the Iazyges fought, assisting Rome in stopping the Dacians' incursions into Roman conquered territory in the first war and defeating the Dacians in the second—are connected with war. Another such war is the Marcomannic War that occurred between 169 and 175, in which time, the Iazyges fought against Rome but were defeated by Marcus Aurelius and had severe penalties imposed on them.

Culture

[edit]Although the Iazyges were nomads before their migration to the Tisza plain, they became semi-sedentary once there, and lived in towns,[4][5][6][7][8] although they migrated between these towns to allow their cattle to graze.[6][9][10] Their language was a dialect of Old Iranian, which was quite different from most of the other Sarmatian dialects of Old Iranian.[11] According to the Roman writer Gaius Valerius Flaccus, when an Iazyx became too old to fight in battle, they were killed by their sons[12][13] or, according to Roman geographer Pomponius Mela, threw themselves from a rock.[14]

Etymology

[edit]The Iazyges' name was Latinized as Iazyges Metanastae (Ἰάζυγες Μετανάσται) or Jazyges,[15] or sometimes as Iaxamatae.[16] Their name was also occasionally spelled as Iazuges.[17] Several corruptions of their name, such as Jazamatae,[18] Iasidae,[19] Latiges, and Cizyges, existed.[20] Other modern English forms of their name are Iazyigs, Iazygians, Iasians, and Yazigs.[21] The root of the name may be Proto-Iranian *yaz-, "to sacrifice", perhaps indicating a caste or tribe specializing in religious sacrifices.[22]

According to Peter Edmund Laurent, a 19th-century French classical scholar, the Iazyges Metanastæ, a warlike Sarmatian race, which had migrated during the reign of the Roman Emperor Claudius, and therefore received the name of "Metanastæ", resided in the mountains west of the Theiss (Tisza) and east of the Gran (Hron) and Danube.[23] The Greek Metanastæ (Greek: Μετανάσται) means "migrants". The united Scythians and Sarmatæ called themselves Iazyges, which Laurent connected with Old Church Slavonic ѩзꙑкъ (językŭ, "tongue, language, people").[24]

Burial traditions

[edit]

The graves made by the Iazyges were often rectangular or circular,[26] although some were ovoid, hexagonal, or even octagonal.[25] They were flat and were grouped like burials in modern cemeteries.[27] Most of the graves' access openings face south, southeast, or southwest. The access openings are between 0.6 metres (2 ft) and 1.1 m (3 ft 7 in) wide. The graves themselves are between 5 m (16 ft) and 13 m (43 ft) in diameter.[25]

After their migration to the Tisza plain, the Iazyges were in serious poverty.[28] This is reflected in the poor furnishings found at burial sites, which are often filled with clay vessels, beads, and sometimes brooches. Iron daggers and swords were very rarely found in the burial site. Their brooches and arm-rings were of the La Tène type, showing the Dacians had a distinct influence on the Iazyges.[27] Later tombs showed an increase in material wealth; tombs of the 2nd to early 4th centuries had weapons in them 86% of the time and armor in them 5% of the time.[29] Iazygian tombs along the Roman border show a strong Roman influence.[30]

Diet

[edit]

Before their migration into the Pannonian Basin, while still living north of Tyras, on the north-western coast of the Black Sea, the geographer Strabo states that their diet consisted largely of "honey, milk, and cheese".[32] After their migration, the Iazyges were cattle breeders; they required salt to preserve their meat[33] but there were no salt mines within their territory.[34] According to Cassius Dio, the Iazyges received grain from the Romans.[35]

The Iazyges used hanging, asymmetrical, barrel-shaped pots that had uneven weight distribution. The rope used to hang the pot was wrapped around the edges of the side collar; it is believed the rope was tied tightly to the pot, allowing it to spin in circles. Due to the spinning motion, there are several theories about the pot's uses. It is believed the small hanging pots were used to store fermented alcohol, some of which have been found to contain seeds of touch-me-not balsam (Impatiens noli-tangere), which has led researchers to hypothesize that some of the fermented beverages were infused with the seeds for the purposes of either cultic practices or medicinal use, while the larger hanging pots were likely used to churn butter and make cheese.[31]

Military

[edit]The Iazyges wore heavy armor, such as sugarloaf helms,[b][37] and scale armor made of iron, bronze, horn, or horse hoof, which was sewn onto a leather gown so the scales would partially overlap.[38][39][40][41] They used long, two-handed lances called contus; they wielded these from horses, which they barded.[c][43] Their military was exclusively cavalry.[44] They are believed to have used saddle blankets on their horses.[45] Although it was originally Gaulish, it is believed the Iazyges used the carnyx, a trumpet-like wind instrument.[46]

Religion

[edit]One of the Iazygian towns, Bormanon, is believed to have had hot springs because settlement names starting with "Borm" were commonly used among European tribes to denote that the location had hot springs, which held religious importance for many Celtic tribes. It is not known, however, whether the religious significance of the hot springs was passed on to the Iazyges with the concept itself.[47] The Iazyges used horse-tails in their religious rituals.[48]

Economy

[edit]When the Iazyges migrated to the plain between the Tisza and the Danube, their economy suffered severely. Many explanations have been offered for this, such as their trade with the Pontic Steppe and Black Sea being cut off and the absence of any mineable resources within their territory making their ability to trade negligible. Additionally, Rome proved more difficult to raid than the Iazyges' previous neighbors, largely due to Rome's well-organized army.[28][49][50] The Iazyges had no large-scale organized production of goods for most of their history.[51] As such, most of their trade goods were gained via small-scale raids upon neighboring peoples, although they did have some incidental horticulture.[52] Several pottery workshops have been found in Banat, which was within the territory of the Iazyges, close to their border with Rome. These pottery workshops were built from the late 3rd century and have been found at Vršac–Crvenka, Grădinari–Selişte, Timişoara–Freidorf, Timişoara–Dragaşina, Hodoni, Pančevo, Dolovo, and Izvin şi Jabuca.[53]

The Iazyges' trade with the Pontic Steppe and Black Sea was extremely important to their economy; after the Marcomannic War, Marcus Aurelius offered them the concession of movement through Dacia to trade with the Roxolani, which reconnected them with the Pontic Steppe trade network.[54][55] This trade route lasted until 260, when the Goths took over Tyras and Olbia, cutting off both the Roxolani's and the Iazyges' trade with the Pontic Steppe.[56] The Iazyges also traded with the Romans, although this trade was smaller in scale. While there are Roman bronze coins scattered along the entirety of the Roman Danubian Limes, the highest concentration of them appear in the Iazyges' territory.[57]

Imports

[edit]Because the Iazyges had no organized production for most of their history, imported pottery finds are sparse. Some goods, such as bronze or silver vessels, amphorae, terracotta wares, and lamps are extremely rare or nonexistent. Some amphorae and lamps have been found in Iazygian territory, often near major river crossings near the border with Rome, but the location of the sites make it impossible to determine whether these goods are part of an Iazygain site, settlement, or cemetery; or merely the lost possessions of Roman soldiers stationed in or near the locations.[58]

The most commonly found imported ware was Terra sigillata. At Iazygian cemeteries, a single complete terra sigillata vessel and a large number of fragments have been found in Banat. Terra sigillata finds in Iazygian settlements are confusing in some cases; it can sometimes be impossible to determine the timeframe of the wares in relation to its area and thus impossible to determine whether the wares came to rest there during Roman times or after the Iazyges took control. Finds of terra sigillata of an uncertain age have been found in Deta, Kovačica–Čapaš, Kuvin, Banatska Palanka, Pančevo, Vršac, Zrenjanin–Batka, Dolovo, Delibata, Perlez, Aradac, Botoš, and Bočar. Finds of terra sigillata that have been confirmed to having been made the time of Iazygian possession but of uncertain date have been found in Timișoara–Cioreni, Hodoni, Iecea Mică, Timișoara–Freidorf, Satchinez, Criciova, Becicherecul Mic, and Foeni–Seliște. The only finds of terra sigillata whose time of origin is certain have been found in Timișoara–Freidorf, dated to the 3rd century AD. Amphorae fragments have been found in Timișoara–Cioreni, Iecea Mică, Timișoara–Freidorf, Satchinez, and Biled; all of these are confirmed to be of Iazygian origin but none of them have definite chronologies.[58]

In Tibiscum, an important Roman and later Iazygian settlement, only a very low percent of pottery imports were imported during or after the 3rd century. The pottery imports consisted of terra sigillata, amphorae, glazed pottery, and stamped white pottery. Only 7% of imported pottery was from the "late period" during or after the 3rd century, while the other 93% of finds were from the "early period", the 2nd century or earlier.[59] Glazed pottery was almost nonexistent in Tibiscum; the only finds from the early period are a few fragments with Barbotine decorations and stamped with "CRISPIN(us)". The only finds from the late period are a handful of glazed bowl fragments that bore relief decorations on both the inside and the outside. The most common type of amphorae is the Dressel 24 similis; finds are from the time of rule of Hadrian to the late period. An amphora of type Carthage LRA 4 dated between the 3rd and 4th century AD has been found in Tibiscum-Iaz and an amphora of type Opaiţ 2 has been found in Tibiscum-Jupa.[60]

Geography

[edit]Records of eight Iazygian towns have been documented; these are Uscenum, Bormanum, Abieta, Trissum, Parca, Candanum, Pessium, and Partiscum.[23][61] There was also a settlement on Gellért Hill.[62] Their capital was at Partiscum, the site of which roughly corresponds with that of Kecskemét, a city in modern-day Hungary.[63][64] It is believed that a Roman road may have traversed the Iazyges' territory for about 200 miles (320 km),[65] connecting Aquincum to Porolissum, and passing near the site of modern-day Albertirsa.[66] This road then went on to connect with the Black Sea city states.[67]

The area of plains between the Danube and Tisza rivers that was controlled by the Iazyges was similar in size to Italy and about 1,000 mi (1,600 km) long.[68][69] The terrain was largely swampland dotted with a few small hills that was devoid of any mineable metals or minerals. This lack of resources and the problems the Romans would face trying to defend it may explain why the Romans never annexed it as a province but left it as a client-kingdom.[49][50]

According to English cartographer Aaron Arrowsmith, the Iazyges Metanastæ lived east (sic) of the [Roman] Dacia separating it from [Roman] Pannonia and Germania.[70] The Iazyges Metanastæ drove Dacians from Pannonia and Tibiscus River (today known as Timiș River).[70]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

In the 3rd century BC the Iazyges lived in modern-day south-eastern Ukraine along the northern shores of the Sea of Azov, which the Ancient Greeks and Romans called the Lake of Maeotis. From there, the Iazyges—or at least some of them—moved west along the shores of the Black Sea into modern-day Moldova and south-western Ukraine.[72][73][74] It is possible the entirety of the Iazyges did not move west and that some of them stayed along the Sea of Azov, which would explain the occasional occurrence of the surname Metanastae; the Iazyges that possibly remained along the Sea of Azov, however, are never mentioned again.[75]

Migration

[edit]

In the 2nd century BC, sometime before 179 BC, the Iazyges began to migrate westward to the steppe near the Lower Dniester. This may have occurred because the Roxolani, who were the Iazyges' eastern neighbors, were also migrating westward due to pressure from the Aorsi, which put pressure on the Iazyges and forced them to migrate westward as well.[18][77][78]

The views of modern scholars as to how and when the Iazyges entered the Pannonian plain are divided. The main source of division is over the issue of if the Romans approved, or even ordered, the Iazyges to migrate, with both sides being subdivided into groups debating the timing of such a migration. Andreas Alföldi states that the Iazyges could not have been present to the north-east and east of the Pannonian Danube unless they had Roman approval. This viewpoint is supported by János Harmatta, who claims that the Iazyges were settled with both the approval and support of the Romans, so as to act as a buffer state against the Dacians. András Mócsy suggests that Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Augur, who was Roman consul in 26 BC, may have been responsible for the settlement of the Iazyges as a buffer between Pannonia and Dacia. However, Mócsy also suggests that the Iazyges may have arrived gradually, such that they initially were not noticed by the Romans. John Wilkes believes that the Iazyges reached the Pannonian plain either by the end of Augustus's rule (14 AD) or some time between 17 and 20 AD. Constantin Daicoviciu suggests that the Iazyges entered the area around 20 AD, after the Romans called upon them to be a buffer state. Coriolan Opreanu supports the theory of the Iazyges being invited, or ordered, to occupy the Pannonian plain, also around 20 AD.[79] Gheorghe Bichir and Ion Horațiu Crișan support the theory that the Iazyges first began to enter the Pannonian plain in large numbers under Tiberius, around 20 AD.[80] The most prominent scholars that state the Iazyges were not brought in by the Romans, or later approved, are Doina Benea, Mark Ščukin, and Jenő Fitz. Doina Benea states that the Iazyges slowly infiltrated the Pannonian plain sometime in the first half of the 1st century AD, without Roman involvement. Jenő Fitz promotes the theory that the Iazyges arrived en masse around 50 AD, although a gradual infiltration preceded it. Mark Ščukin states only that the Iazyges arrived by themselves sometime around 50 AD. Andrea Vaday argued against the theory of a Roman approved or ordered migration, citing the lack of strategic reasoning, as the Dacians were not actively providing a threat to Rome during the 20–50 AD period.[81]

The occupation of the lands between the Danube and Tisza by the Iazyges was mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia (77–79 AD), in which he says that the Iazyges inhabited the basins and plains of the lands, while the forested and mountainous area largely retained a Dacian population, which was later pushed back to the Tisza by the Iazyges. Pliny's statements are corroborated by the earlier accounts of Seneca the Younger in his Quaestiones Naturales (61–64 AD), where he uses the Iazyges to discuss the borders that separate the various peoples.[79]

From 78 to 76 BC, the Romans led an expedition to an area north of the Danube—then the Iazyges' territory—because the Iazyges had allied with Mithridates VI of Pontus, with whom the Romans were at war.[82][83] In 44 BC King Burebista of Dacia died and his kingdom began to collapse. After this, the Iazyges began to take possession of the Pannonian Basin, the land between the Danube and Tisa rivers in modern-day south-central Hungary.[84] Historians have posited this was done at the behest of the Romans, who sought to form a buffer state between their provinces and the Dacians to protect the Roman province of Pannonia.[85][86][87][88][89][90] The Iazyges encountered the Basternae and Getae along their migration path sometime around 20 AD and turned southward to follow the coast of the Black Sea until they settled in the Danube Delta.[77] This move is attested by the large discrepancy in the location reported by Tacitus relative to that which was earlier given by Ovid.[91] Archeological finds suggest that while the Iazyges took hold of the northern plain between the Danube and the Tisa by around 50 AD, they did not take control of the land south of the Partiscum-Lugio line until the late 1st or early 2nd century.[92]

The effects of this migration have been observed in the ruins of burial sites left behind by the Iazyges; the standard grave goods made of gold being buried alongside a person were absent, as was the equipment of a warrior; this may have been because the Iazyges were no longer in contact with the Pontic Steppe and were cut off from all trade with them, which had previously been a vital part of their economy. Another problem with the Iazyges' new location was that it lacked both precious minerals and metals, such as iron, which could be turned into weapons. They found it was much more difficult to raid the Romans, who had organized armies around the area, as opposed to the disorganized armies of their previous neighbors. The cutting-off of trade with the Pontic Steppe meant they could no longer trade for gold for burial sites, assuming any of them could afford it. The only such goods they could find were the pottery and metals of the adjacent Dacian and Celtic peoples. Iron weapons would have been exceedingly rare, if the Iazyges even had them, and would likely have been passed down from father to son rather than buried because they could not have been replaced.[28]

Post-migration

[edit]

After the conquest of the Pannonian Basin, the Iazyges appear to have ruled over some measure of the remaining Germanic, Celtic, and Dacian populations, with the hilly areas north of modern-day Budapest retaining strong Germanic traditions, with a significant presence of Germanic burial traditions.[93] Items of Celtic manufacturing appear up until the late 2nd century AD, in the northern area of the Carpathian Basin.[94]

During the time of Augustus, the Iazyges sent an embassy to Rome to request friendly relations.[41] In a modern context, these "friendly relations" would be similar to a non-aggression pact.[95] Around this time, some of the western parts of the land of the Iazyges were occupied, apparently without conflict, by the Quadi, which scholar Nicholas Higham states "suggests long-term collaboration between [them]".[93]

Later, during the reign of Tiberius, the Iazyges became one of many new client-tribes of Rome. Roman client states were treated according to the Roman tradition of patronage, exchanging rewards for service.[96][97] The client king was called socius et amicus Romani Populi (ally and friend of the Roman People); the exact obligations and rewards of this relationship, however, are vague.[98] Even after being made into a client state, the Iazyges conducted raids across their border with Rome, for example in 6 AD and again in 16 AD. In 20 AD the Iazyges moved westward along the Carpathians into the Pannonian Steppe, and settled in the steppes between the Danube and the Tisza river, taking absolute control of the territory from the Dacians.[77] In 50 AD, an Iazyges cavalry detachment assisted King Vannius, a Roman client-king of the Quadi, in his fight against the Suevi.[99][100]

In the Year of Four Emperors, 69 AD, the Iazyges gave their support to Vespasian, who went on to become the sole emperor of Rome.[101] The Iazyges also offered to guard the Roman border with the Dacians to free up troops for Vespasian's invasion of Italy; Vespasian refused, however, fearing they would attempt a takeover or defect. Vespasian required the chiefs of the Iazyges to serve in his army so they could not organize an attack on the undefended area around the Danube.[102][103][104][105][106] Vespasian enjoyed support from the majority of the Germanic and Dacian tribes.[101]

Domitian's campaign against Dacia was mostly unsuccessful; the Romans, however, won a minor skirmish that allowed him to claim it as a victory, even though he paid the King of Dacia, Decebalus, an annual tribute of eight million sesterces in tribute to end the war.[101][107] Domitian returned to Rome and received an ovation, but not a full triumph. Considering that Domitian had been given the title of Imperator—for military victories 22 times, this was markedly restrained, suggesting the populace—or at least the senate—was aware it had been a less-than-successful war, despite Domitian's claims otherwise.[108][d] In 89 AD, however, Domitian invaded the Iazyges along with the Quadi and Marcomanni. Few details of this war are known but it is recorded that the Romans were defeated,[110] it is, however, known that Roman troops acted to repel simultaneous incursion by the Iazyges into Dacian lands.[111]

In early 92 AD the Iazyges, Roxolani, Dacians, and Suebi invaded the Roman province of Pannonia—modern-day Croatia, northern Serbia, and western Hungary.[108][112][113] Emperor Domitian called upon the Quadi and the Marcomanni to supply troops to the war. Both client-tribes refused to supply troops so Rome declared war upon them as well. In May 92 AD, the Iazyges annihilated the Roman Legio XXI Rapax in battle.[108][113][114] Domitian, however, is said to have secured victory in this war by January of the next year.[115] It is believed, based upon a rare Aureus coin showing an Iazyx with a Roman standard kneeling, with the caption of "Signis a Sarmatis Resitvtis", that the standard is taken from the annihilated Legio XXI Rapax was returned to Rome at the end of the war.[116] Although the accounts of the Roman-Iazyges wars of 89 and 92 AD are both muddled, it has been shown they are separate wars and not a continuation of the same war.[117] The threat presented by the Iazyges and neighbouring people to the Roman provinces was significant enough that Emperor Trajan travelled across the Mid and Lower Danube in late 98 to early 99, where he inspected existing fortification and initiated the construction of more forts and roads.[111]

Tacitus, a Roman Historian, records in his book Germania, which was written in 98 AD, that the Osi tribes paid tribute to both the Iazyges and the Quadi, although the exact date this relationship began is unknown.[118]

During the Flavian dynasty, the princes of the Iazyges were trained in the Roman army, officially as an honor but in reality serving as a hostage, because the kings held absolute power over the Iazyges.[119] There were offers from the princes of the Iazyges to supply troops but these were denied because of the fear they might revolt or desert in a war.[120]

Dacian wars

[edit]An alliance between the Iazyges and the Dacians led the Romans to focus more on the Danube than the Rhine.[121] This is shown by the placement of the Roman legions; during the time of Augustus's rule there were eight legions stationed along the Rhine, four stationed in Mainz, and another four in Cologne. Within a hundred years of Augustus' rule, however, Roman military resources had become centered along the Danube rather than the Rhine,[101] with nine legions stationed along the Danube and only one at the Rhine. By the time of Marcus Aurelius, however, twelve legions were stationed along the Danube.[121] The Romans also built a series of forts along the entire right bank of the Danube—from Germany to the Black Sea—and in the provinces of Rhaetia, Noricum, and Pannonia the legions constructed bridge-head forts. Later, this system was expanded to the lower Danube with the key castra of Poetovio, Brigetio, and Carnuntum. The Classis Pannonica and Classis Flavia Moesica were deployed to the right and lower Danube, respectively; they, however, had to overcome the mass of whirlpools and cataracts of the Iron Gates.[121]

First Dacian War

[edit]Trajan, with the assistance of the Iazyges, led his legions[e] into Dacia against King Decebalus, in the year 101.[6][122] In order to cross the Danube with such a large army, Apollodorus of Damascus, the Romans' chief architect, created a bridge through the Iron Gates by cantilevering it from the sheer face of the Iron Gates. From this he created a great bridge with sixty piers that spanned the Danube. Trajan used this to strike deep within Dacia, forcing the king, Decebalus, to surrender and become a client king.[123]

Second Dacian War

[edit]As soon as Trajan returned to Rome, however, Decebalus began to lead raids into Roman territory and also attacked the Iazyges, who were still a client-tribe of Rome.[124][125] Trajan concluded that he had made a mistake in allowing Decebalus to remain so powerful.[123] In 106 AD, Trajan again invaded Dacia, with 11 legions, and, again with the assistance of the Iazyges[122][6]—who were the only barbarian tribe that aided the Romans in this war —[f][127] and the only barbarian tribe in the Danube region which did not ally with Dacia.[127] The Iazyges were the only tribe to aid Rome in both Dacian Wars,[6][128] pushed rapidly into Dacia. Decebalus chose to commit suicide rather than be captured, knowing that he would be paraded in a triumph before being executed. In 113 AD Trajan annexed Dacia as a new Roman province, the first Roman province to the east of the Danube. Trajan, however, did not incorporate the steppe between the Tisza river and the Transylvanian mountains into the province of Dacia but left it for the Iazyges.[129] Back in Rome, Trajan was given a triumph lasting 123 days, with lavish gladiatorial games and chariot races. The wealth coming from the gold mines of Dacia funded these lavish public events and the construction of Trajan's Column, which was designed and constructed by Apollodorus of Damascus; it was 100 feet (30 m) tall and had 23 spiral bands filled with 2,500 figures, giving a full depiction of the Dacian war. Ancient sources say 500,000 slaves were taken in the war but moderns sources believe it was probably closer to 100,000 slaves.[130]

After the Dacian Wars

[edit]

Ownership of the region of Oltenia became a source of dispute between the Iazyges and the Roman empire. The Iazyges had originally occupied the area before the Dacians seized it; it was taken during the Second Dacian War by Trajan, who was determined to constitute Dacia as a province.[122][136][137] The land offered a more direct connection between Moesia and the new Roman lands in Dacia, which may be the reason Trajan was determined to keep it.[138] The dispute led to war in 107–108, where the future emperor Hadrian, then governor of Pannonia Inferior, defeated them.[122][136][139] The exact terms of the peace treaty are not known, but it is believed the Romans kept Oltenia in exchange for some form of concession, likely involving a one-time tribute payment.[122] The Iazyges also took possession of Banat around this time, which may have been part of the treaty.[140]

In 117, the Iazyges and the Roxolani invaded Lower Pannonia and Lower Moesia, respectively. The war was probably brought on by difficulties in visiting and trading with each other because Dacia lay between them. The Dacian provincial governor Gaius Julius Quadratus Bassus was killed in the invasion. The Roxolani surrendered first, so it is likely the Romans exiled and then replaced their client king with one of their choosing. The Iazyges then concluded peace with Rome.[141] The Iazyges and other Sarmatians invaded Roman Dacia in 123, likely for the same reason as the previous war; they were not allowed to visit and trade with each other. Marcius Turbo stationed 1,000 legionaries in the towns Potaissa and Porolissum, which the Romans probably used as the invasion point into Rivulus Dominarum. Marcius Turbo succeeded in defeating the Iazyges; the terms of the peace and the date, however, are not known.[142]

Marcomannic Wars

[edit]

In 169, the Iazyges, Quadi, Suebi, and Marcomanni once again invaded Roman territory. The Iazyges led an invasion into Alburnum in an attempt to seize its gold mines.[143] The exact motives for and directions of the Iazyges' war efforts are not known.[144] Marcus Claudius Fronto, who was a general during the Parthian wars and then the governor of both Dacia and Upper Moesia, held them back for some time but was killed in battle in 170.[145] The Quadi surrendered in 172, the first tribe to do so; the known terms of the peace are that Marcus Aurelius installed a client-king Furtius on their throne and the Quadi were denied access to the Roman markets along the limes. The Marcomanni accepted a similar peace but the name of their client-king is not known.[146]

In 173, the Quadi rebelled and overthrew Furtius and replaced him with Ariogaesus, who wanted to enter into negotiations with Marcus. Marcus refused to negotiate because the success of the Marcomannic wars was in no danger.[146] At that point the Iazyges had not yet been defeated by Rome. having not acted, Marcus Aurelius appears to have been unconcerned, but when the Iazyges attacked across the frozen Danube in late 173 and early 174, Marcus redirected his attention to them. Trade restrictions on the Marcomanni were also partially lifted at that time; they were allowed to visit the Roman markets at certain times of certain days. In an attempt to force Marcus to negotiate, Ariogaesus began to support the Iazyges.[147] Marcus Aurelius put out a bounty on him, offering 1,000 aurei for his capture and delivery to Rome or 500 aurei for his severed head.[148][h] After this, the Romans captured Ariogaesus but rather than executing him, Marcus Aurelius sent him into exile.[150]

In the winter of 173, the Iazyges launched a raid across the frozen Danube but the Romans were ready for pursuit and followed them back to the Danube. Knowing the Roman legionaries were not trained to fight on ice, and that their own horses had been trained to do so without slipping, the Iazyges prepared an ambush, planning to attack and scatter the Romans as they tried to cross the frozen river. The Roman army, however, formed a solid square and dug into the ice with their shields so they would not slip. When the Iazyges could not break the Roman lines, the Romans counter-attacked, pulling the Iazyges off of their horses by grabbing their spears, clothing, and shields. Soon both armies were in disarray after slipping on the ice and the battle was reduced to many brawls between the two sides, which the Romans won. After this battle the Iazyges—and presumably the Sarmatians in general—were declared the primary enemy of Rome.[151]

The Iazyges surrendered to the Romans in March or early April of 175.[152][153][154] Their prince Banadaspus had attempted peace in early 174 but the offer was refused and Banadaspus was deposed by the Iazyges and replaced with Zanticus.[i][147] The terms of the peace treaty were harsh; the Iazyges were required to provide 8,000 men as auxiliaries and release 100,000 Romans they had taken hostage,[j] and were forbidden from living within ten Roman miles (roughly 9 miles (14 km) of the Danube. Marcus had intended to impose even harsher terms; it is said by Cassius Dio that he wanted to entirely exterminate the Iazyges[157] but was distracted by the rebellion of Avidius Cassius.[147] During this peace deal, Marcus Aurelius broke from the Roman custom of Emperors sending details of peace treaties to the Roman Senate; this is the only instance in which Marcus Aurelius is recorded to have broken this tradition.[158] Of the 8,000 auxiliaries, 5,500 of them were sent to Britannia[159] to serve with the Legio VI Victrix,[160] suggesting that the situation there was serious; it is likely the British tribes, seeing the Romans being preoccupied with war in Germania and Dacia, had decided to rebel. All of the evidence suggests the Iazyges' horsemen were an impressive success.[159] The 5,500 troops sent to Britain were not allowed to return home, even after their 20-year term of service had ended.[161] After Marcus Aurelius had beaten the Iazyges; he took the title of Sarmaticus in accordance with the Roman practice of victory titles.[162]

After the Marcomannic Wars

[edit]In 177, the Iazyges, the Buri, and other Germanic tribes[k] invaded Roman territory again.[55] It is said that in 178, Marcus Aurelius took the bloody spear from the Temple of Bellona and hurled it into the land of the Iazyges.[164] In 179, the Iazyges and the Buri were defeated, and the Iazyges accepted peace with Rome. The peace treaty placed additional restrictions on the Iazyges but also included some concessions. They could not settle on any of the islands of the Danube and could not keep boats on the Danube. They were, however, permitted to visit and trade with the Roxolani throughout the Dacian Province with the knowledge and approval of its governor, and they could trade in the Roman markets at certain times on certain days.[55][165] In 179, the Iazyges and the Buri joined Rome in their war against the Quadi and the Marcomanni after they secured assurances that Rome would prosecute the war to the end and not quickly make a peace deal.[166]

As part of a treaty made in 183, Commodus forbade the Quadi and the Marcomanni from waging war against the Iazyges, the Buri, or the Vandals, suggesting that at this time all three tribes were loyal client-tribes of Rome.[167][168] In 214, however, Caracalla led an invasion into the Iazyges' territory.[169] In 236, the Iazyges invaded Rome but were defeated by Emperor Maximinus Thrax, who took the title Sarmaticus Maximus following his victory.[170] The Iazyges, Marcomanni, and Quadi raided Pannonia together in 248,[171][172] and again in 254.[173] It is suggested the reason for the large increase in the amount of Iazyx raids against Rome was that the Goths led successful raids, which emboldened the Iazyges and other tribes.[174] In 260, the Goths took the cities of Tyras and Olbia, again cutting off the Iazyges' trade with the Pontic Steppe and the Black Sea.[56] From 282 to 283, Emperor Carus lead a successful campaign against the Iazyges.[173][175]

The Iazyges and Carpi raided Roman territory in 293, and Diocletian responded by declaring war.[176] From 294 to 295, Diocletian waged war upon them and won.[177][178] As a result of the war, some of the Carpi were transported into Roman territory so they could be controlled.[179] From 296 to 298, Galerius successfully campaigned against the Iazyges.[175][180] In 358, the Iazyges were at war with Rome.[181] In 375, Emperor Valentinian had a stroke in Brigetio while meeting with envoys from the Iazyges.[l][183] Around the time of the Gothic migration, which led the Iazyges to be surrounded on their northern and eastern borders by Gothic tribes, and most intensely during the reign of Constantine I, a series of earthworks known as the Devil's Dykes (Ördögárok) was built around the Iazygian territory,[184][185] possibly with a degree of Roman involvement. Higham suggests that the Iazyges became more heavily tied to the Romans during this period, with strong cultural influence.[185]

Late history and legacy

[edit]

In late antiquity, historic accounts become much more diffuse and the Iazyges generally cease to be mentioned as a tribe.[186][187] Beginning in the 4th century, most Roman authors cease to distinguish between the different Sarmatian tribes, and instead refer to all as Sarmatians.[188] In the late 4th century, two Sarmatian peoples were mentioned—the Argaragantes and the Limigantes, who lived on opposite sides of the Tisza river. One theory is that these two tribes were formed when the Roxolani conquered the Iazyges, after which the Iazyges became the Limigantes and the Roxolani became the Argaragantes.[186][187] Another theory is that a group of Slavic tribesmen who gradually migrated into the area were subservient to the Iazyges; the Iazyges became known as the Argaragantes and the Slavs were the Limigantes.[189] Yet another theory holds that the Roxolani were integrated into the Iazyges.[190] Regardless of which is true, in the 5th century both tribes were conquered by the Goths[191][192][193][194] and, by the time of Attila, they were absorbed into the Huns.[195]

Foreign relations

[edit]The Roman Empire

[edit]The Iazyges often harassed the Roman Empire after their arrival in the Pannonian Basin, but they never rose to become a true threat.[196] During the 1st century, Rome used diplomacy to secure their northern borders, especially on the Danube, by way of befriending the tribes, and by sowing distrust amongst the tribes against each other.[197] Rome defended their Danubian border not just by way of repelling raids, but also by levying diplomatic influence against the tribes and launching punitive expeditions.[198][199][200] The combination of diplomatic influence and swift punitive expeditions allowed the Romans to force the various tribes, including the Iazyges, into becoming client states of the Roman Empire.[200] Even after the Romans abandoned Dacia, they consistently projected their power north of the Danube against the Sarmatian tribes, especially during the reigns of Constantine, Constantius II, and Valentinian.[201] To this end, Constantine constructed a permanent bridge across the middle Danube in order to improve logistics for campaigns against the Goths and Sarmatians.[200][202]

Another key part of the relationship between the Roman Empire and the Sarmatian tribes was the settling of tribes in Roman lands, with emperors often accepting refugees from the Sarmatian tribes into nearby Roman territory.[203] When the Huns arrived in the Russian steppes and conquered the tribes that were there, they often lacked the martial ability to force the newly conquered tribes to stay, leading to tribes like the Greuthungi, Vandals, Alans, and Goths migrating and settling within the Roman Empire rather than remaining subjects of the Huns.[204] The Roman Empire benefited from accepting these refugee tribes, and thus continued to allow them to settle, even after treaties were made with Hunnic leaders such as Rugila and Attila that stipulated that the Roman Empire would reject all refugee tribes, with rival or subject tribes of the Huns being warmly received by Roman leaders in the Balkans.[205]

Archeology

[edit]Around the time of Trajan, the Romans established routes between Dacia and Pannonia, with evidence of Roman goods appearing in Iazygian land occurring around 100 AD, largely centered near important river crossings. Additionally, a small number of Roman inscriptions and buildings were made during this period, which scholar Nicholas Higham states suggests either a high degree of Romanization or the presence of diplomatic or military posts within Iazygian territory. Roman goods were widespread in the second and early third century AD, especially near Aquincum, the capital of Roman Pannonia Inferior, and the area east to the Tizsa valley.[206]

Roxolani

[edit]The Iazyges also had a strong relationship with the Roxolani, another Sarmatian tribe, both economically and diplomatically.[55][139][165][200] During the second Dacian War, where the Iazyges supported the Romans, while the Roxolani supported the Dacians, the Iazyges and Roxolani remained neutral to each other.[207] After the Roman annexation of Dacia, the two tribes were effectively isolated from each other, until the 179 peace concession from Emperor Marcus Aurelius which permitted the Iazyges and Roxolani to travel through Dacia, subject to the approval of the governor.[55][165][200] Because of the new concession allowing them to trade with the Roxolani they could, for the first time in several centuries, trade indirectly with the Pontic Steppe and the Black Sea.[54] It is believed the Iazyges traveled through Small Wallachia until they reached the Wallachian Plain, but there is little archeological evidence to prove this.[208] Cypraea shells began to appear in this area in the last quarter of the 2nd century.[209]

Quadi

[edit]The scholar Higham suggests that there was some degree of "long-term collaboration" between the Iazyges and the Quadi, noting that they were allied in the late 2nd century AD, and that the Iazyges ceded the western portions of their land to them shortly after arriving in the Pannonian Basin, apparently without conflict.[93]

List of princes

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Singular Iazyx, /ˈaɪəzɪks/; Latin: [ˈjaːzːygeːs] and [ˈjaːzːyks], respectively; Ancient Greek: Ἰάζυγες, singular Ἰάζυξ.

- ^ Sugarloaf helms are a type of conical great helm.[36]

- ^ Barding is the practice of giving armor to a horse to protect it.[42]

- ^ Some sources say that Domitian was offered a triumph, but refused.[109]

- ^ Presumably around nine of them, because during this period nine legions were permanently stationed around the Danube.[121]

- ^ It was said by some Roman leaders, such as Quadratus, that it was crucial to the Romans that the Iazyges not join in on the Dacian side.[126]

- ^ Cichorius identified them as Iazyges, but Frere and Lepper have identified them as Roxolani.[131][132]

- ^ The most likely reason Marcus Aurelius offered more for him alive than dead is that he planned to parade him in a triumph, which was the standard Roman treatment of captured leaders.[149]

- ^ Cassius Dio claims it was Marcus Aurelius rather than the Iazyges who imprisoned Banadaspus.[155]

- ^ This number is significant, as the Marcomanni, for whom the war is named after, took only 30,000 hostages. The disparity was enough that Cassius Dio said that the war should have been called the Iazygian War.[156]

- ^ The only Germanic tribe that is named is the Buri, but there were more.[55]

- ^ Some sources say that the meeting was with the Quadi and not the Iazyges.[182]

References

[edit]- ^ Coppadoro 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Leisering 2004, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Map after Ptolemy's Geographia.

- ^ Constantinescu, Pascu & Diaconu 1975, p. 60.

- ^ Dise 1991, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e Leslie 1999, p. 168.

- ^ Kardulias 1998, p. 249.

- ^ Castellan 1989, p. 12.

- ^ Pounds 1993, p. 52.

- ^ Fehér 2017, p. 23.

- ^ Harmatta 1970, p. 96.

- ^ Wijsman 2000, p. 2.

- ^ Parkin 2003, p. 263.

- ^ Wijsman 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Smith 1873, p. 7.

- ^ Todd 2002, p. 60.

- ^ Korkkanen 1975, p. 66.

- ^ a b Cook & Adcock 1965, p. 93.

- ^ Bolecek 1973, p. 149.

- ^ Goodyear 2004, p. 700.

- ^ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 879.

- ^ Lebedynsky 2014, pp. 188 & 251.

- ^ a b Laurent 1830, p. 157.

- ^ Laurent 1830, p. 311.

- ^ a b c Bârcă & Cociş 2013, p. 41.

- ^ Bârcă & Simonenko 2009, p. 463.

- ^ a b Bacon & Lhote 1963, p. 293.

- ^ a b c Harmatta 1970, pp. 43–45.

- ^ Mode & Tubach 2006, p. 438.

- ^ Brogan 1936, p. 202.

- ^ a b Views concerning barrel‑shaped vessels in the Sarmatian Iazyges environment.

- ^ Higham 2018, p. 44.

- ^ Groenman-Van Waateringe 1997, p. 250.

- ^ Vagalinski 2007, p. 177.

- ^ Academia România 1980, p. 224.

- ^ Tschen-Emmons 2015, p. 38.

- ^ MacKendrick 1975, p. 88.

- ^ Hinds 2009, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Erdkamp 2007, p. 747.

- ^ Summer & D'Amato 2009, p. 191.

- ^ a b Stover 2012, p. 9.

- ^ G.G. Lepage 2014, p. 97.

- ^ McLaughlin 2016, p. 148.

- ^ Ridgeway 2015, p. 116.

- ^ von Hesberg 1990, p. 287.

- ^ Daicoviciu 1960, p. 152.

- ^ Dowden 2013, p. 45.

- ^ Preble 1980, p. 69.

- ^ a b McLynn 2010, p. 366.

- ^ a b Sedgwick 1921, p. 171.

- ^ Harmatta 1970, p. 44.

- ^ Lacy 1976, p. 78.

- ^ Grumeza 2016, p. 69.

- ^ a b Harmatta 1970, pp. 45–47.

- ^ a b c d e f Mócsy 2014, p. 191.

- ^ a b Harmatta 1970, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Du Nay & Kosztin 1997, p. 28.

- ^ a b Grumeza 2016, p. 70.

- ^ Grumeza 2016, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Grumeza 2016, p. 71.

- ^ Klaudios Ptolemaios. Handbuch der Geographie. Griechisch-Deutsch. Herausgegeben von Alfred Stückelberger und Gerd Graßhoff. Schwabe Verlag Basel. 2006, p. 310-311

- ^ Mulvin 2002, p. 18.

- ^ Perenyi 1973, p. 170.

- ^ Gutkind 1964, p. 372.

- ^ Williams 1997, p. 91.

- ^ Lambrechts 1949, p. 213.

- ^ Krebs 2000, p. 234.

- ^ Grainger 2004, p. 112.

- ^ Petit 1976, p. 37.

- ^ a b Arrowsmith 1839, p. 105.

- ^ Ethno-Political map of ancient Eurasia.

- ^ McLynn 2010, p. 313.

- ^ Grumeza 2009, p. 40.

- ^ Quigley 1983, p. 509.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen & Knight 1973, p. 448.

- ^ Johnston 1867, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Cunliffe 2015, p. 284.

- ^ Bunson 1995, p. 367.

- ^ a b Bârcă 2013, p. 104.

- ^ Bârcă 2013, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Bârcă 2013, p. 105.

- ^ Hildinger 2001, p. 50.

- ^ Hinds 2009, p. 71.

- ^ Mócsy 2014, p. 21.

- ^ Harmatta 1970, p. 42.

- ^ Daicoviciu & Condurachi 1971, p. 100.

- ^ Goffart 2010, p. 80.

- ^ Dzino 2010, p. 168.

- ^ Williams 1997, p. 64.

- ^ Cook & Adcock 1965, p. 85.

- ^ Williams 1994, p. 6.

- ^ Bârcă 2013, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Higham 2018, p. 47.

- ^ Higham 2018, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Sands 2016, p. 13.

- ^ Luttwak 1981, p. 21.

- ^ Salway 1982, p. 208.

- ^ Elton 1996, p. 12.

- ^ Malcor & Littleton 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Bârcă & Cociş 2013, p. 104.

- ^ a b c d McLynn 2010, p. 314.

- ^ McLaughlin 2016, p. 147.

- ^ Hoyos 2013, p. 221.

- ^ Henderson 1927, p. 158.

- ^ Master 2016, p. 135.

- ^ Saddington 1982, pp. 41 & 115.

- ^ Jones 1993, p. 150.

- ^ a b c Grainger 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Murison 1999, p. 254.

- ^ Mattingly 2010, p. 94.

- ^ a b Bârcă 2013, p. 18.

- ^ Henderson 1927, p. 166.

- ^ a b Jones 1908, p. 143.

- ^ Swan 2004, p. 165.

- ^ Ryberg 1967, p. 30.

- ^ Tsetskhladze 2001, p. 424.

- ^ Habelt 1967, p. 122.

- ^ Hastings, Selbie & Gray 1921, p. 589.

- ^ Wellesley 2002, p. 133.

- ^ Ash & Wellesley 2009, p. 3–5.

- ^ a b c d McLynn 2010, p. 315.

- ^ a b c d e Mócsy 2014, p. 94.

- ^ a b McLynn 2010, p. 319.

- ^ Bunson 2002, p. 170.

- ^ Hoyos 2013, p. 255.

- ^ Corson 2003, p. 179.

- ^ a b Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 98.

- ^ Wilkes 1984, p. 73.

- ^ Mócsy 2014, p. 95.

- ^ McLynn 2010, p. 320.

- ^ Boardman & Palaggiá 1997, p. 200.

- ^ Strong 2015, p. 193.

- ^ Cichorius 1988, p. 269.

- ^ Eggers et al. 2004, p. 505.

- ^ Kemkes 2000, p. 51.

- ^ a b Giurescu & Fischer-Galaţi 1998, p. 39.

- ^ Mellor 2012, p. 506.

- ^ Lengyel & Radan 1980, p. 94.

- ^ a b Bârcă 2013, p. 19.

- ^ Mócsy 2014, p. 101.

- ^ Mócsy 2014, p. 100.

- ^ Grumeza 2009, p. 200.

- ^ Kean & Frey 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Williams 1997, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Mócsy 2014, p. 187.

- ^ a b Mócsy 2014, p. 189.

- ^ a b c d e Mócsy 2014, p. 190.

- ^ Beckmann 2011, p. 198.

- ^ Beard 2009, p. 121.

- ^ Bunson 2002, p. 36.

- ^ McLaughlin 2016, p. 164.

- ^ Helmolt 1902, p. 444.

- ^ Erdkamp 2007, p. 1026.

- ^ Levick 2014, p. 171.

- ^ Watson 1884, p. 211.

- ^ Williams 1997, p. 178.

- ^ McLynn 2010, p. 360.

- ^ Sabin, Wees & Whitby 2007, p. 7.

- ^ a b McLynn 2010, p. 368.

- ^ Snyder 2008, p. 55.

- ^ Piotrovsky 1976, p. 151.

- ^ Loetscher & Jackson 1977, p. 175.

- ^ Sedov 2012, p. 322.

- ^ Ulanowski 2016, p. 362.

- ^ a b c Găzdac 2010, p. 51.

- ^ Regenberg 2006, p. 191.

- ^ McLynn 2010, p. 423.

- ^ Merrills & Miles 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Sydenham, Sutherland & Carson 1936, p. 84.

- ^ Giurescu & Matei 1974, p. 32.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2009, p. 111.

- ^ Marks & Beatty 1976, p. 37.

- ^ a b Drăgan 1985, p. 73.

- ^ Matyszak 2014, p. 141.

- ^ a b Tsetskhladze 2001, p. 429.

- ^ Neusner 1990, p. 231.

- ^ Syme 1971, p. 226.

- ^ Boak 1921, p. 319.

- ^ Duruy 1887, p. 373.

- ^ Kuiper 2011, p. 174.

- ^ Hornblower 2012, p. 723.

- ^ Bury 2013, p. 65.

- ^ Venning & Harris 2006, p. 26.

- ^ Williams 1997, p. 256.

- ^ a b Higham 2018, p. 66.

- ^ a b Constantinescu, Pascu & Diaconu 1975, p. 65.

- ^ a b Zahariade 1998, p. 82.

- ^ Ţentea, Opriș & Popescu 2009, p. 129.

- ^ Hoddinott 1963, p. 78.

- ^ Harmatta 1970, pp. 54–58.

- ^ Smith 1873, p. 8.

- ^ Laurent 1830, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Frere, Hartley & Wacher 1983, p. 255.

- ^ Chadwick 2014, p. 70.

- ^ Várdy 1991, p. 18.

- ^ Scheidel 2019, p. 292.

- ^ Dudley 1993, p. 165.

- ^ Ricci 2015, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Ricci 2015, p. 211.

- ^ a b c d e Ricci 2015, p. 18.

- ^ Ricci 2015, p. 17.

- ^ Kulikowski 2007, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Ricci 2015, p. 19.

- ^ Ricci 2015, p. 22.

- ^ Ricci 2015, p. 27–29.

- ^ Higham 2018, p. 48.

- ^ Bârcă 2013, p. 117.

- ^ Barkóczi & Vaday 1999, p. 249.

- ^ Carnap-Bornheim 2003, p. 220.

- ^ Stover 2012, p. 130.

- ^ Kleywegt 2005, p. 44.

- ^ Kramer & Reitz 2010, p. 448.

- ^ Le Beau 1827, p. 44.

Sources

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Ammianus Marcellinus in Res Gestae (22.30)

- Cassius Dio in Roman History (67.5, 68.10, 69.15–22, 71.7–17, 72, 73.2)

- Eutropius in Eutropii Breviarium (7.23, 8.3)

- Flaccus in Argonautica (173–180)

- Gaius Valerius Flaccus in Argonautica (6.323−339, 7.123, 7.288)

- Pliny the Elder in Natural History (4.80−81)

- Ptolemy in Geography (3.5–8)

- Strabo in Geography (2.5, 7.2−3, 11.2–5)

- Suetonius in De vita Caesarum (12.6)

- Tacitus in The History (1.79, 2.80−81, 3.5), The Annals (12.29–30), and Agricola (41)

- Xiphilinus in Epitome of Dio (250.17–251.22, 259–260)

Modern sources

[edit]Books

[edit]- Academia România (1980). Bibliotheca historica Romaniae: Monographs. Academia Republicii Socialiste România. Secția de Științe Istorice. OCLC 1532822.

- Arrowsmith, Aaron (1839). Grammar of Ancient Geography: Compiled for the Use of King's College School. S. Arrowsmith et al. ISBN 978-1-377-71123-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Ash, Rhiannon; Wellesley, Kenneth (2009). The Histories (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-194248-3.

- Bacon, Edward; Lhote, Henri (1963). Vanished Civilizations of the Ancient World. McGraw-Hill. LCCN 63014869. OCLC 735510932.

- Bârcă, Vitalie (2013). Nomads of the Steppes on the Danube Frontier of the Roman Empire in the 1st Century CE. Historical Sketch and Chronological Remarks. Dacia. OCLC 1023761641.

- Bârcă, Vitalie; Cociş, Sorin (2013). Sarmatian Graves Surrounded By Flat Circular Ditch Discovered At Nădlac. Ephemeris Napocensis. OCLC 7029405883.

- Bârcă, Vitalie; Simonenko, Oleksandr (2009). Călăreţii stepelor: sarmaţii în spaţiul nord-pontic (Horsemen of the steppes : the Sarmatians in the North Pontic region). Editura Mega. ISBN 978-606-543-027-3.

- Barkóczi, László; Vaday, Andrea H. (1999). Pannonia And Beyond: studies In Honour of László Barkóczi. Archaeological Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. OCLC 54895323.

- Beard, Mary (2009). The Roman triumph. Belknap. ISBN 978-0-674-02059-7.

- Beckmann, Martin (2011). Column of Marcus Aurelius the Genesis and Meaning of a Roman Imperial Monument. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-7777-7.

- Boak, Arthur Edward Romilly (1921). A History of Rome to 565 A. D. Macmillan. OCLC 1315742.

- Boardman, John; Palaggiá, Olga (1997). Greek offerings: essays on Greek art in honour of John Boardman. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-900188-44-9.

- Bolecek, B. V. (1973). Ancient Slovakia: Archeology and History. Slovak Academy. OCLC 708160.

- Brogan, Olwen (1936). "Trade between the Roman Empire and the Free Germans". Journal of Roman Studies. 26 (2). Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: 195–222. doi:10.2307/296866. JSTOR 296866. S2CID 163349328.

- Bunson, Matthew (1995). A Dictionary of the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510233-8.

- Bunson, Matthew (2002). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. Facts On File. ISBN 978-1-4381-1027-1.

- Bury, J. B. (2013). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: Edited in Seven Volumes with Introduction, Notes, Appendices, and Index. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-05073-9.

- Carnap-Bornheim, Claus von (2003). Kontakt, Kooperation, Konflikt : Germanen und Sarmaten zwischen dem 1. und dem 4. Jahrhundert nach Christus; internationales Kolloquium des Vorgeschichtlichen Seminars der Philipps-Universität Marburg, 12. – 16. Februar 1998. Wachholtz. ISBN 978-3-529-01871-8.

- Castellan, George (1989). A History of the Romanians. East European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-88033-154-8.

- Chadwick, H. Munro (2014). The Nationalities of Europe and the Growth of National Ideologies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-64287-4.

- Cichorius, Conrad (1988). Trajan's Column: A New Edition of the Chicorius Plates (New ed.). Sutton. ISBN 978-0-86299-467-9.

- Constantinescu, Miron; Pascu, Ștefan; Diaconu, Petre (1975). Relations Between the Autochthonous Population and the Migratory Populations on the Territory of Romania: A Collection of Studies. Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România. OCLC 928080934.

- Cook, S. A.; Adcock, Frank (1965). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Imperial peace, A.D. 70-192, 1965. Cambridge University Press. OCLC 3742485.

- Coppadoro, John (2010). Antonio Maria Viani e la facciata di Palazzo Guerrieri a Mantova (in Italian). Alinea. ISBN 978-88-6055-491-8.

- Corson, David (2003). Trajan and Plotina. iUnivserse. ISBN 978-0-595-28044-5.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2015). By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968917-0.

- Daicoviciu, Constantin (1960). Omagiu lui Constantin Daicoviciu cu Prilejul împlinirii a 60 de ani. București. OCLC 186919895.

- Daicoviciu, Constantin; Condurachi, Emil (1971). Romania. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 978-0-214-65256-1.

- Dise, Robert L. (1991). Cultural Change And Imperial Administration: The Middle Danube Provinces Of The Roman Empire. P. Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-1465-2.

- Dowden, Ken (2013). European Paganism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-81022-2.

- Drăgan, Iosif Constantin (1985). Dacia's Imperial Millennium. Nagard Publishing. OCLC 17605220.

- Du Nay, Alain; Kosztin, Árpád (1997). Transylvania and the Rumanians. Corvinus. ISBN 978-1-882785-09-4.

- Dudley, Donald R. (1993). The Civilization of Rome. Penguin Group Inc. ISBN 978-0-452-01016-1.

- Duruy, Victor (1887). History of Rome, and of the Roman People, from Its Origin to the Establishment of the Christian Empire. D. Estes ad C. E. Lauriat. OCLC 8441167.

- Dzino, Danijel (2010). Illyricum in Roman Politics, 229 BC–AD 68. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48423-7.

- Eggers, Martin; Beck, Heinrich; Hoops, Johannes; Müller, Rosemarie (2004). Saal – Schenkung. De Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017734-X.

- Elton, Hugh (1996). Frontiers of the Roman Empire. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33111-3.

- Erdkamp, Paul (2007). A Companion to the Roman Army. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-2153-8.

- Fehér, Alexander (2017). Vegetation History and Cultural Landscapes: Case Studies from South-west Slovakia. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-60267-7.

- Frere, Sheppard Sunderland; Hartley, Brian; Wacher, J. S. (1983). Rome and her northern provinces : papers presented to Sheppard Frere in honour of his retirement from the Chair of the Archaeology of the Roman Empire, University of Oxford, 1983. A. Sutton. ISBN 978-0-86299-046-6.

- G.G. Lepage, Jean-Denis (2014). Medieval Armies and Weapons in Western Europe: An Illustrated History. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6251-3.

- Găzdac, Cristian (2010). Monetary circulation in Dacia and the provinces from the Middle and Lower Danube from Trajan to Constantine I (AD 106-337). Ed. Mega. ISBN 978-606-543-040-2.

- Giurescu, Dinu C.; Fischer-Galaţi, Stephen A. (1998). Romania: a Historic Perspective. East European Monographs. OCLC 39317152.

- Giurescu, Constantin C.; Matei, Horia C. (1974). Chronological history of Romania. National Commission of the Socialist Republic of Romania for UNESCO. OCLC 802144986.

- Goffart, Walter (2010). Barbarian Tides the Migration Age and the Later Roman Empire. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0028-7.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome fell death of a superpower. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15560-0.

- Goodyear, F. R. D. (2004). The Classical Papers of A. E. Housman:, Volume 2; Volumes 1897–1914. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-60696-7.

- Grainger, John D. (2004). Nerva and the Roman Succession Crisis of AD 96–99. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-34958-1.

- Groenman-Van Waateringe, Willy (1997). Roman frontier studies: proceedings of the ... International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-900188-47-0.

- Grumeza, Ion (2009). Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe. Hamilton Books. ISBN 978-0-7618-4466-2.

- Grumeza, Laviana (2016). Settlements From The 2nd–Early 5th Century AD In Banat. West University of Timișoara. doi:10.14795/j.v2i4.144.

- Gutkind, E.A. (1964). Urban development in Western Europe, France and Belgium. Free Press. OCLC 265099.

- Habelt, Rudolf (1967). Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. JSTOR. OCLC 1466587.

- Harmatta, J. (1970). Studies in the History and Language of the Sarmatians. Acta Universitatis de Attila József Nominatae. Acta antique et archaeologica. University of Szeged Press. OCLC 891848847.

- Hastings, James; Selbie, John Alexander; Gray, Louis Herbert (1921). Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics: Sacrifice-Sudra. T. & T. Clark. OCLC 3065458.

- Helmolt, Hans Ferdinand (1902). The World's History: The Mediterranean nations. W. Heinemann. OCLC 621610.

- Henderson, Bernard William (1927). Five Roman emperors: Vespasian, Titus, Domitian, Nerva, Trajan, A.D. 69-117. CUP Archive. OCLC 431784232.

- Higham, Nicholas (2018). King Arthur: The Making of the Legend. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21092-7.

- Hildinger, Erik (2001). Warriors of the Steppe: A Military History of Central Asia, 500 B.C. to 1700 A.D. Da Capo. ISBN 978-0-306-81065-7.

- Hinds, Kathryn (2009). Scythians and Sarmatians. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-7614-4519-7.

- Hoddinott, Ralph F. (1963). Early Byzantine churches in Macedonia and southern Serbia: a study of the origins and the initial development of East Christian art. Macmillan. OCLC 500216.

- Hornblower, Simon (2012). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2013). A companion to Roman imperialism. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-23646-2.

- Johnston, Alexander Keith (1867). School Atlas of Classical Geography: Comprising, in Twenty-three Plates. William Blackwood and Sons. OCLC 11901919.

- Jones, Henry Stuart (1908). The Roman Empire, B.C.29-A.D.476, Part 476. G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 457652445.

- Jones, Brian W. (1993). The Emperor Domitian (New ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10195-0.

- Kardulias, Nick P. (1998). World-Systems Theory in Practice Leadership, Production, and Exchange. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4616-4743-0.

- Kean, Roger Michael; Frey, Oliver (2005). The complete chronicle of the emperors of Rome. Thalamus. ISBN 978-1-902886-05-3.

- Kemkes, Schriftleitung: Martin (2000). Von Augustus bis Attila: Leben am ungarischen Donaulimes : [erschienen anlässlich der gleichnamigen Sonderausstellung des Ungarischen Nationalmuseums, Budapest] (in German). Limesmuseum. ISBN 978-3-8062-1541-0.

- Kleywegt, A.J. (2005). Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica, Book I: a commentary. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-13924-4.

- Korkkanen, Irma (1975). The peoples of Hermanaric: Jordanes, Getica 116. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. ISBN 978-951-41-0231-8.

- Kramer, Norbert; Reitz, Christiane (2010). Tradition and Renewal: Medial strategies in the time of the Flavians. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-024715-2.

- Krebs, Steven A. (2000). Settlement in Classical Dobrogea. Indiana University. OCLC 46777015.

- Kuiper, Kathleen (2011). Ancient Rome: From Romulus and Remus to the Visigoth Invasion. Britannica Educational Publications. ISBN 978-1-61530-107-2.

- Kulikowski, Michael (2007). Rome's Gothic Wars from the Third Century to Alaric. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-60868-8.

- Lacy, Christabel (1976). The Greek View of Barbarians in the Hellenistic Age: As Derived from Representative Literary and Artistic Evidence from the Hellenistic Period. University of Colorado. OCLC 605385551.

- Lambrechts, Pierre (1949). Prof. Dr. Hubert van de Weerd; een vooraanstaand figuur der Gentse Universiteit (in German). De Tempel. OCLC 5222953.

- Laurent, Peter Edmund (1830). An Introduction to the Study of Ancient Geography (2nd ed.). Henry Slatter. OCLC 19988268. Copy at Google books (searching Metanastae)

- Le Beau, Charles (1827). Histoire du Bas-Empire (in French). Desaint [et] Saillant. OCLC 6752757.

- Lebedynsky, Iaroslav (2014). Les Sarmates amazones et lanciers cuirassés entre Oural et Danube (VIIe siècle av. J.-C. – VIe siècle apr. J.-C.). Éd. Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-565-1.

- Leisering, Walter (2004). Historischer Weltatlas (in German). Marix. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-3-937715-59-9.

- Lengyel, A.; Radan, G.T. (1980). The Archaeology of Roman Pannonia. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-963-05-1886-4.

- Leslie, Alan (1999). Theoretical Roman archaeology & architecture : the third conference proceedings. Cruithne Press. ISBN 978-1-873448-14-4.

- Levick, Barbara M. (2014). Faustina I and II: imperial women of the golden age. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-970217-6.

- Loetscher, Lefferts A.; Jackson, Samuel Macauley (1977). The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Baker Book House. ISBN 978-0-8010-7947-4.

- Luttwak, Edward N. (1981). The Grand Strategy of the Roman empire: From the First Century A.D. to the third. Hopkin. ISBN 978-0-8018-2158-5.

- MacKendrick, Paul (1975). The Dacian stones speak. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1226-6.

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto J.; Knight, Max (1973). The World of the Huns: Studies in their History and Culture. University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-01596-8.

- Malcor, Linda A.; Littleton, C. Scott (2013). From Scythia to Camelot: A Radical Reassessment of the Legends of King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table, and the Holy Grail. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-77771-7.

- Marks, Geoffrey; Beatty, William K. (1976). Epidemics. Scribnerś Sons. ISBN 978-0-684-15893-8.

- Master, Jonathan (2016). Provincial Soldiers and Imperial Instability in the Histories of Tacitus. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11983-7.

- Mattingly, H. (2010). Agricola and Germania. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-196154-5.

- Matyszak, Philip (2014). The Roman Empire. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-78074-425-4.

- McLaughlin, Raoul (2016). The Roman Empire and the Silk Routes: The Ancient World Economy and the Empires of Parthia, Central Asia and Han China. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4738-8982-8.

- McLynn, Frank (2010). Marcus Aurelius: A Life. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81916-2.

- Mellor, Ronald (2012). The Historians of Ancient Rome: An Anthology of the Major Writings. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-22261-0.

- Merrills, Andy; Miles, Richard (2010). The Vandals. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-1808-1.

- Mócsy, András (April 8, 2014). Pannonia and Upper Moesia (Routledge Revivals): A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-75425-1.

- Mode, Markus; Tubach, Jürgen (2006). Arms and Armour as Indicators of Cultural Transfer: the Steppes and the Ancient World from Hellenistic Times to the Early Middle Ages. Reichert. ISBN 978-3-89500-529-9.

- Mulvin, Lynda (2002). Late Roman Villas in the Danube-Balkan Region. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-84171-444-8.

- Murison, Charles Leslie (1999). Rebellion and Reconstruction: Galba to Domitian; an Historical Commentary on Cassius Dio's Roman History, Books 64 - 67 (A.D. 68 – 96). Scholars Press. ISBN 978-0-7885-0547-8.

- Neusner, Jacob (1990). History of the Jews in the second through seventh centuries of the Common Era. Garland Pub. ISBN 978-0-8240-8179-9.

- Parkin, Tim G. (2003). Old age in the Roman world: a cultural and social history. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7128-3.

- Perenyi, Imre (1973). Town Centres. Planning and Renewal. Akademiai Kiado. ISBN 978-0-569-07702-6.

- Petit, Paul (1976). Pax Romana. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02171-6.

- Piotrovsky, Boris (1976). From the Lands of the Scythians: Ancient Treasures From The Museums of the U.S.S.R., 3000 B.C.-100 B.C. New York Graphic Society. ISBN 978-0-87099-143-1.

- Pop, Ioan Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (2006). History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute. ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4.

- Pounds, N.J.G. (1993). An historical geography of Europe. Cambridge University. ISBN 978-0-521-31109-0.

- Preble, George Henry (1980). The Symbols, Standards, Flags, and Banners of Ancient and Modern Nations. Flag Research Center. ISBN 978-0-8161-8476-7.

- Quigley, Carroll (1983). Weapons Systems and Political Stability: a History. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-2947-5.

- Regenberg, W. (2006). Bullettino dell'Instituto archeologico germanico, Sezione romana (112 ed.). Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. OCLC 1566507.

- Ricci, Giuseppe A. (2015). Nomads in Late Antiquity: Gazing on Rome from the Steppe, Attila to Asparuch (370–680 C.E.). Princeton University. OCLC 953142610.

- Ridgeway, William (2015). The Origin and Influence of the Thoroughbred Horse. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-50223-9.

- Ryberg, Inez Scott (1967). Panel Reliefs of Marcus Aurelius. Archaeological Institute of America. OCLC 671875431.

- Sabin, Philip; Wees, Hans van; Whitby, Michael (2007). The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78274-6.

- Saddington, D.B. (1982). The Development of the Roman Auxiliary Forces From Caesar to Vespasian: 49 B.C.–79 A.D. University of Zimbabwe. ISBN 978-0-86924-078-6.

- Salway, Peter (1982). Roman Britain. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821717-6.

- Sands, P.C. (2016). The Client Princes of the Roman Empire Under the Republic. Palala Press. ISBN 978-1-355-85963-5.

- Scheidel, Walter (2019). Escape from Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity. Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvg25294.13. JSTOR ctvg25294.13. S2CID 243226679.

- Sedgwick, Henry Dwight (1921). Marcus Aurelius; a Biography Told as Much as May be by Letters: Together with Some Account of the Stoic Religion and an Exposition of the Roman Government's Attempt to Suppress Christianity During Marcus's Reign. Yale University Press. OCLC 153517.

- Sedov, Valentin Vasiljevič (2012). Sloveni u dalekoj prošlosti (in Serbian). Akademska knjiga. ISBN 978-86-6263-022-3.

- Smith, William (1873). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (2nd ed.). J. Murray. OCLC 2371051.

- Snyder, Christopher A. (2008). The Britons. Blackwell Pub. ISBN 978-0-470-75821-2.

- Stover, Tim (2012). Epic and empire in Vespasianic Rome: a new reading of Valerius Flaccus' Argonautica. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-964408-7.

- Strong, Eugénie (2015). Roman Sculpture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-07810-8.

- Summer, Graham; D'Amato, Raffaele (2009). Arms and Armour of the Imperial Roman Soldier. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-84832-512-8.

- Swan, Peter Michael (2004). The Augustan Succession: An Historical Commentary on Cassius Dio's Roman History Books 55-56 (9 B.C.-A.D. 14). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534714-2.

- Sydenham, Edward Allen; Sutherland, Carol Humphrey Vivian; Carson, Robert Andrew Glendinning (1936). The Roman Imperial Coinage. Spink. OCLC 10528222.

- Syme, Ronald (1971). Emperors And Biography: Studies In The 'Historia Augusta'. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814357-4.

- Ţentea, Ovidiu; Opriș, Ioan C.; Popescu, Mariana-Cristina (2009). Near and Beyond the Roman Frontiers: Proceedings of a Colloquium Held in Târgoviște. National History Museum of Romania. OCLC 909836612.

- Todd, Malcolm (2002). Migrants & invaders: the movement of peoples in the ancient world. Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-1437-9.

- Tschen-Emmons, James B. (2015). Artifacts from Medieval Europe. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-622-7.

- Tsetskhladze, Gocha R. (2001). North Pontic Archaeology: Recent Discoveries and Studies. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12041-9.

- Ulanowski, Krzysztof (2016). The Religious Aspects of War in the Ancient Near East, Greece, and Rome: Ancient Warfare Series (1st ed.). BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-32476-3.

- Vagalinski, Lyudmil Ferdinandov (2007). The lower Danube in antiquity (VI C BC – VI C AD) : international archaeological Conference, Bulgaria-Tutrakan. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, National Institute of Archaeology and Museum. ISBN 978-954-90387-8-1.

- Várdy, Steven Béla (1991). Attila: King of the Huns. Chelsea House. ISBN 978-1-55546-803-3.

- Venning, T.; Harris, J. (2006). Chronology of the Byzantine Empire. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-50586-5.

- von Hesberg, Henner (1990). Bullettino dell'Instituto archeologico germanico, Sezione romana. Philipp von Zabern Verlag. OCLC 637572094.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European peoples (2nd ed.). Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4964-6.

- Watson, Paul Barron (1884). Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. Harper & brothers. ISBN 9780836956672. OCLC 940511169.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Wellesley, Kenneth (2002). Year of the Four Emperors. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-56227-5.

- Wijsman, Henri J.W. (2000). Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica, Book VI : a commentary. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11718-1.

- Wilkes, John (1984). The Roman Army: Cambridge Introduction to the History of Mankind. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-07243-4.

- Williams, Gareth D. (1994). Banished Voices: Readings in Ovid's Exile Poetry. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45136-9.

- Williams, Derek (1997). The Reach of Rome: a History of the Roman Imperial Frontier 1st-5th centuries AD. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-15631-2.

- Zahariade, Mihail (1998). The Roman Frontier at the Lower Danube, 4th-6th centuries. Romanian Institute of Thracology. ISBN 978-973-98829-3-4.

Websites

[edit]- Bulat, V. "Ethno-Political map of ancient Eurasia". gumilevica.kulichki.net (in Russian). Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "The British Library MS Viewer". www.bl.uk. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Muscalu, Bogdan. "Views concerning barrel‑shaped vessels in the Sarmatian Iazyges environment". Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Bennett, Julian (1997). Trajan: Optimus Princeps. Bloomington, IN: Indianapolis University Press. ISBN 978-0-415-24150-2.

- Birley, Anthony (1987). Marcus Aurelius: A Biography. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-415-17125-0.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 215. OCLC 954463552.

- Christian, David (1999). A History of Russia, Mongolia and Central Asia, Vol. 1. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-20814-3.

- Istvánovits, Eszter; Kulcsár, Valéria (2020). "Sarmatians on the Borders of the Roman Empire: Steppe Traditions and Imported Cultural Phenomena". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 26 (2): 391–402. doi:10.1163/15700577-12341381. S2CID 234571926.

- Kerr, William George (1995). A Chronological Study of the Marcomannic Wars of Marcus Aurelius. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. OCLC 32861447.

- Kristó, Gyula (1998). Magyarország története – 895–1301 [The History of Hungary – From 895 to 1301]. Budapest: Osiris. ISBN 963-379-442-0.

- Macartney, C. A. (1962). Hungary: A Short History. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-00-612410-8.

- Peck, Harry Thurston (1898). Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. New York: Harper and Brothers. ISBN 978-1-163-24933-8.

- Strayer, Joseph R., editor in chief (1987). A Dictionary of the Middle Ages. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-684-80642-6.

External links

[edit] Media related to Iazyges at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Iazyges at Wikimedia Commons

Iazyges

View on GrokipediaThe Iazyges were a Sarmatian tribe of eastern Iranian nomadic origin that migrated westward from the Pontic-Caspian steppes around 200 BC, eventually settling in the Great Hungarian Plain between the Danube and Tisza rivers by the early 1st century AD, where they transitioned toward a semi-sedentary pastoralist society.[1][2] Known for their elite heavy cavalry equipped with long lances and scale armor, the Iazyges maintained a warrior aristocracy that dominated the region through military prowess and tribute extraction from local Celtic and Dacian populations.[3] Their interactions with the Roman Empire were marked by repeated raids across the Danube frontier, prompting punitive campaigns, yet also alliances as auxiliaries, culminating in decisive defeats during the Marcomannic Wars (166–180 AD) under Emperor Marcus Aurelius, who imposed harsh terms including the surrender of 8,000 cavalrymen and hostages dispatched to Britain.[4] By the 3rd century AD, Iazygian power waned amid Gothic invasions and internal fragmentation, leading to the absorption of remnants into Roman forces or subsequent barbarian confederations like the Huns.[5] Archaeological evidence, including flat inhumation graves and distinctive pottery, underscores their cultural synthesis of steppe traditions with local influences, distinguishing them from more purely nomadic Sarmatian kin.[6]

Etymology and Origins

Linguistic and Cultural Affiliation

The Iazyges were linguistically affiliated with the Sarmatians, a confederation of eastern Iranian-speaking nomadic peoples originating from the Eurasian steppes. Their language belonged to the Scytho-Sarmatian branch of Eastern Iranian dialects, distinct from Median or Persian varieties but sharing phonological and morphological features traceable to Proto-Iranian.[7] This affiliation is evidenced by anthroponyms and ethnonyms preserved in classical sources, such as the tribal name Iazyges, potentially deriving from Iranian roots like yazuka- ("youthful" or "young"), as reconstructed through comparative analysis with Ossetic and Avestan cognates.[8] Similarly, leader names like Banadaspos exhibit Iranian etymologies, with elements analyzable as compounds involving terms for "similar" or locative suffixes akin to those in modern Kurdish and ancient Iranian languages, underscoring a continuity from steppe Iranian nomadism.[9] Culturally, the Iazyges embodied core Sarmatian traits, including equestrian nomadism, heavy cavalry tactics with scale-armored cataphracts, and a warrior aristocracy emphasizing archery and lances, as depicted in Roman reliefs and corroborated by archaeological finds of horse gear and weapons in the Carpathian Basin.[10] Their material culture featured steppe-derived elements like tamgas (tribal brands) on artifacts, limited to elite Sarmatian subgroups, and burial practices with rich grave goods reflecting social hierarchy and mobility, distinct from neighboring Celtic or Dacian sedentary traditions.[11] While interactions with Romans introduced some hybrid elements, such as fortified settlements by the 2nd century CE, primary cultural markers—nomadic pastoralism, polyandry in elite strata, and Iranian-derived onomastics—persisted, affirming their Sarmatian identity over local assimilations.[12] This continuity is supported by genetic and isotopic studies showing steppe ancestry dominance in Iazygian burials, aligning with Iranian nomadic heritage rather than substantial admixture until late antiquity.[13]Genetic and Archaeological Evidence for Eastern Roots