Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

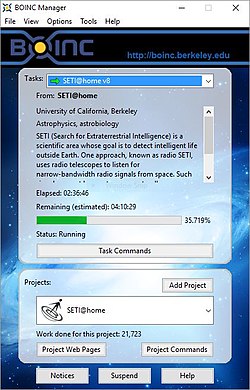

Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing

View on Wikipedia| BOINC | |

|---|---|

| |

BOINC Manager Simple View | |

| Developer | University of California, Berkeley |

| Initial release | 10 April 2002 |

| Stable release | |

| Preview release | 8.2.5

/ 15 July 2025 |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C++ (client/server) PHP (project CMS) Java/Kotlin (Android client) |

| Operating system | Windows macOS Linux Android FreeBSD Raspberry Pi OS |

| Type | Grid computing and volunteer computing |

| License | LGPL-3.0-or-later[1] Project licensing varies |

| Website | boinc |

The Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing[2] (BOINC, pronounced /bɔɪŋk/ –rhymes with "oink"[3]) is an open-source middleware system for volunteer computing (a type of distributed computing).[4] Developed originally to support SETI@home,[5] it became the platform for many other applications in areas as diverse as medicine, molecular biology, mathematics, linguistics, climatology, environmental science, and astrophysics, among others.[6] The purpose of BOINC is to enable researchers to utilize processing resources of personal computers and other devices around the world.

BOINC development began with a group based at the Space Sciences Laboratory (SSL) at the University of California, Berkeley, and led by David P. Anderson, who also led SETI@home. As a high-performance volunteer computing platform, BOINC brings together 34,236 active participants employing 136,341 active computers (hosts) worldwide, processing daily on average 20.164 PetaFLOPS as of 16 November 2021[update][7] (it would be the 21st largest processing capability in the world compared with an individual supercomputer).[8] The National Science Foundation (NSF) funds BOINC through awards SCI/0221529,[9] SCI/0438443[10] and SCI/0721124.[11] Guinness World Records ranks BOINC as the largest computing grid in the world.[12]

BOINC code runs on various operating systems, including Microsoft Windows, macOS, Android,[13] Linux, and FreeBSD.[14] BOINC is free software released under the terms of the GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL).

History

[edit]BOINC was originally developed to manage the SETI@home project. David P. Anderson has said that he chose its name because he wanted something that was not "imposing", but rather "light, catchy, and maybe - like 'Unix' - a little risqué", so he "played around with various acronyms and settled on 'BOINC'".[15]

The original SETI client was a non-BOINC software exclusively for SETI@home. It was one of the first volunteer computing projects, and not designed with a high level of security. As a result, some participants in the project attempted to cheat the project to gain "credits", while others submitted entirely falsified work. BOINC was designed, in part, to combat these security breaches.[16]

The BOINC project started in February 2002, and its first version was released on April 10, 2002. The first BOINC-based project was Predictor@home, launched on June 9, 2004. In 2009, AQUA@home deployed multi-threaded CPU applications for the first time,[17] followed by the first OpenCL application in 2010.

As of 15 August 2022, there are 33 projects on the official list.[18] There are also, however, BOINC projects not included on the official list. Each year, an international BOINC Workshop is hosted to increase collaboration among project administrators. In 2021, the workshop was hosted virtually.[19]

While not affiliated with BOINC officially, there have been several independent projects that reward BOINC users for their participation, including Charity Engine (sweepstakes based on processing power with prizes funded by private entities who purchase computational time of CE users), Bitcoin Utopia (now defunct), and Gridcoin (a blockchain which mints coins based on processing power).

Design and structure

[edit]BOINC is software that can exploit the unused CPU and GPU cycles on computer hardware to perform scientific computing. In 2008, BOINC's website announced that Nvidia had developed a language called CUDA that uses GPUs for scientific computing. With NVIDIA's assistance, several BOINC-based projects (e.g., MilkyWay@home. SETI@home) developed applications that run on NVIDIA GPUs using CUDA. BOINC added support for the ATI/AMD family of GPUs in October 2009. The GPU applications run from 2 to 10 times faster than the former CPU-only versions. GPU support (via OpenCL) was added for computers using macOS with AMD Radeon graphic cards, with the current BOINC client supporting OpenCL on Windows, Linux, and macOS. GPU support is also provided for Intel GPUs.[20]

BOINC consists of a server system and client software that communicate to process and distribute work units and return results.

Mobile application

[edit]A BOINC app also exists for Android, allowing every person owning an Android device – smartphone, tablet and/or Kindle – to share their unused computing power. The user is allowed to select the research projects they want to support, if it is in the app's available project list.

By default, the application will allow computing only when the device is connected to a WiFi network, is being charged, and the battery has a charge of at least 90%.[21] Some of these settings can be changed to users needs. Not all BOINC projects are available[22] and some of the projects are not compatible with all versions of Android operating system or availability of work is intermittent. Currently available projects[22] are Asteroids@home, Einstein@Home, LHC@home, Moo! Wrapper, Rosetta@home, World Community Grid and Yoyo@home. As of September 2021, the most recent version of the mobile application can only be downloaded from the BOINC website or the F-Droid repository as the official Google Play store does not allow downloading and running executables not signed by the app developer and each BOINC project has their own executable files.

User interfaces

[edit]BOINC can be controlled remotely by remote procedure calls (RPC), from the command line, and from a BOINC Manager. BOINC Manager currently has two "views": the Advanced View and the Simplified GUI. The Grid View was removed in the 6.6.x clients as it was redundant. The appearance (skin) of the Simplified GUI is user-customizable, in that users can create their own designs.

Account managers

[edit]A BOINC Account Manager is an application that manages multiple BOINC project accounts across multiple computers (CPUs) and operating systems. Account managers were designed for people who are new to BOINC or have several computers participating in several projects. The account manager concept was conceived and developed jointly by GridRepublic and BOINC. Current and past account managers include:

- BAM! (BOINC Account Manager) (The first publicly available Account Manager, released for public use on May 30, 2006)

- GridRepublic (Follows the ideas of simplicity and neatness in account management)

- Charity Engine (Non-profit account manager for hire, uses prize draws and continuous charity fundraising to motivate people to join the grid)

- Science United (An account manager designed to make BOINC easier to use which automatically selects vetted BOINC projects for users based on desired research areas such as "medicine" or "physics")[23]

- Dazzler (Open-source Account Manager, to ease institutional management resources)

Credit system

[edit]- The BOINC Credit System is designed to avoid bad hardware and cheating by validating results before granting credit.

- The credit management system helps to ensure that users are returning results which are both statistically and scientifically accurate.

- Online volunteer computing is a complicated and variable mix of long-term users, retiring users and new users with different personal aspirations.

Projects

[edit]BOINC is used by many groups and individuals. Some BOINC projects are based at universities and research labs while others are independent areas of research or interest.[24]

Active

[edit]| Project Name | Publications | Launched | Status | Operating System | GPU App | Sponsor | Category | Research Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| climateprediction.net | 152 papers[25] | 2003-12-09 | 307,359 volunteers[26] | Windows, Linux, ARM, macOS[27] | No | Oxford University | Climate change | Improve climate prediction models. Sub-project: Seasonal Attribution Project. |

| Einstein@Home | 42 papers[28] | 2005-02-19 | 1,041,796 volunteers[29] | Windows, Linux, ARM, macOS, Android[30] | GPU CPU | University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, Max Planck Institute | Astrophysics | Search for pulsars using radio signals and gravitational wave data |

| Gerasim@Home | 9 papers[31] | 2007-02-10 | 6,811 volunteers[32] | Windows, Linux[33] | No | Southwest State University (Russia) | Multiple applications | Research in discrete mathematics and logic control systems |

| GoofyxGrid@Home | 2016 | No | Independent | Mathematics | Mathematically implement the Infinite monkey theorem | |||

| GPUGRID.net | 53 papers[34] | 2007-12-05 | 46,874 volunteers[35] | Windows, Linux, macOS[36] | NVIDIA GPU only | Barcelona Biomedical Research Park | Molecular biology | Perform full-atom molecular simulations of proteins on Nvidia GPUs for biomedical research |

| iThena | 2 papers[37][38] | 2019 | 507,079[39] + 180,789[40] volunteers | Windows, Linux, ARM[41] | No | Cyber-Complex Foundation (Poland) | Internet | Measurements and analyses of global Internet architecture structures |

| LHC@home | 71 papers[42] | 2004-01-09 | 178,623 volunteers[43] | Windows, Linux, ARM, macOS, Android, FreeBSD[44] | No | CERN | Physics | Help construct and test the Large Hadron Collider and search for fundamental particles |

| MilkyWay@home | 27 papers[45] | 2007-07-07 | 250,447 volunteers[46] | Windows, Linux, macOS[47] | No | Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute | Astronomy | Create a simulation of the Milky Way galaxy using data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey |

| PrimeGrid | 3 papers[48] | 2005-06-12 | 353,261 volunteers[49] | Windows, Linux, macOS[50] | GPU CPU | Independent | Mathematics | Search for primes such as Generalized Fermat primes, 321 primes, Sierpiński numbers, Cullen-Woodall primes, Proth prime, and Sophie Germain primes. Subprojects include Seventeen or Bust, Riesel Sieve, and AP27 Search. |

| RALPH@Home | Rosetta@home | 2006-02-15 | 5548 volunteers[51] | Windows, Linux, ARM, macOS, Android[52] | GPU CPU | University of Washington | Molecular biology | Test project for Rosetta@home |

| Rosetta@home | 234 papers[53] | 2005-10-06 | 1,373,480 volunteers[54] | Windows, Linux, ARM, macOS, Android[55] | No | University of Washington | Molecular biology | Protein structure prediction for disease research |

| Tn-grid | 8 papers[56] | 2013-12-19 | 3,201 volunteers[57] | Windows, Linux, macOS[58] | No | University of Trento | Genetics | Currently deploying gene@home work to expand gene networks |

| World Community Grid | 77 papers[59] | 2004-11-16 | 85,119 volunteers[60] | Windows, Linux, ARM, macOS, Android[61] | GPU CPU | Krembil Research Institute | Multiple applications | Subprojects: Open Pandemics - COVID-19. Clean Energy Project, GO Drug Search for Leishmaniasis, Fight Against Malaria, Computing for Clean Water, Discovering Dengue Drugs - Together, OpenZika, Help Cure Muscular Dystrophy, Help Defeat Cancer, Help Conquer Cancer, Help Fight Childhood Cancer, Smash Childhood Cancer, Human Proteome Folding Project, Uncovering Genome Mysteries, FightAIDS@Home, Let's outsmart Ebola together, Mapping Cancer Markers, Help Stop TB. |

| Yoyo@home | 9 papers[62] | 2007-07-19 | 94,236 volunteers[63] | Windows, Linux, macOS, Android, ARM, Solaris, Sony Playstation 3[64] | No | Independent | Multiple applications | Using the BOINC Wrapper with existing volunteer projects |

Completed

[edit]| Project Name | Publications | Launched | Status | Operating System | GPU app | Sponsor | Category | Research Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC@Home | paper[65] | 2006-11-21 | No | Mathematical Institute of Leiden University | Mathematics | Find triples of the ABC conjecture | ||

| AQUA@home | 4 papers[66] | 2008-12-10 | GPU CPU | D-Wave Systems | Computer science | Predict the performance of Quantum computers | ||

| Artificial Intelligence System | No | Intelligence Realm Inc | Artificial intelligence | Simulate the brain using Hodgkin–Huxley models via an artificial neural network | ||||

| Big and Ugly Rendering Project (BURP) | 2 papers[67] | 2004-06-17 | No | Independent | Rendering (computer graphics) | Use BOINC infrastructure with Blender (software) to render animated videos | ||

| Collatz Conjecture project | paper[68] | 2009-01-06[69] | 67,719 volunteers[70] | Windows, Linux, macOS[71] | GPU CPU | Independent | Mathematics | Study the unsolved Collatz conjecture[72] |

| Correlizer | 5 papers[73] | 2011[74] | No | Biology | Examining genome organization | |||

| Cosmology@Home | 5 papers[75] | 2007-06-26 | 87,465 volunteers[76] | Windows, Linux, macOS[77] | No | Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris | Astronomy | Develop simulations that best describe The Universe |

| Docking@Home | 20 papers[78] | 2006-09-11[79] | No | University of Delaware | Molecular biology | Use the CHARMM program to model protein-ligand docking. The goal was the development of pharmaceutical drugs. | ||

| EDGeS@Home | 12 papers[80] | 2009-10 | No | MTA SZTAKI Laboratory of Parallel and Distributed Systems | Multiple applications | Support of scientific applications developed by the EGEE and EDGeS community | ||

| eOn | 6 papers[81] | No | University of Texas at Austin | Chemistry | Theoretical chemistry techniques to solve problems in condensed matter physics and materials science | |||

| Evolution@Home | 6 papers[82] | No | Evolutionary Biology | Improve understanding of evolutionary processes | ||||

| FreeHAL | 2006 | No | Independent | Artificial intelligence | Compute information for software to imitate human conversation | |||

| HashClash | 11 papers[83] | 2005-11-24 | No | Eindhoven University of Technology | Cryptography | Find collisions in the MD5 hash algorithm | ||

| Ibercivis | 18 papers[84] | 2008-06-22 | No | Zaragoza, CETA-CIEMAT, CSIC, Coimbra | Multiple applications | Research in physics, material science and biomedicines | ||

| Leiden Classical | 2 papers[85] | 2005-05-12 | No | Leiden University | Chemistry | Classical mechanics for students and scientists | ||

| Malaria Control Project | 26 papers[86] | 2006-12-19 | No | Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute | Model Diseases | Stochastic modelling of clinical epidemiology and the natural history of Plasmodium falciparum malaria | ||

| MindModeling@Home | 6 papers[87] | 2007-07-07 | 24,574 volunteers[88] | Windows, Linux, macOS[89] | No | University of Dayton Research Institute and Wright State University | Cognitive science | Making cognitive models of the human mind |

| uFluids@Home | 3 papers[90] | 2005-09-19 | No | Purdue University | Physics, Aeronautics | A computer simulation of two-phase flow behavior in microgravity and micro fluidics | ||

| OProject@Home | paper[91] | 2012-08-13 | No | Olin Library, Rollins College | Mathematics | Algorithm analysis. The library is open and available in the Code.google.com SVN repository. | ||

| orbit@home | paper[92] | 2008-04-03 | No | Planetary Science Institute | Astronomy | Monitor near-earth asteroids | ||

| Pirates@home | 2004-06-02 | No | 1 Vassar College

2 Spy Hill Research |

Software testing | Mission 1: Test BOINC software and help to develop Einstein@Home screensaver[93]

Mission 2: Develop forum software for Interactions in Understanding the Universe[94] | |||

| POEM@Home | 5 papers[95] | 2007-13-11 | No | University of Karlsruhe | Molecular biology | Model Protein folding using Anfinsen's dogma | ||

| Predictor@home | 5 papers[96] | 2004-05-04 | No | The Scripps Research Institute | Molecular biology | Test new methods of protein structure prediction and algorithms in the context of the Sixth Biannual CASP[97] experiment | ||

| proteins@home | 4 papers[98] | 2006-09-15 | No | École polytechnique | Protein structure prediction | Contribute to a better understanding of many diseases and pathologies and to progress in Medicine and Technology | ||

| QMC@Home | 7 papers[99] | 2006-03-03 | No | University of Münster | Chemistry | Study the structure and reactivity of molecules using quantum chemistry and Monte Carlo techniques | ||

| Quake-Catcher Network | 13 papers[100] | 2008-02-03 | No | Stanford University, then | Seismology | Use accelerometers connected to personal computers and devices to detect earthquakes and to educate about seismology | ||

| Riesel Sieve | No | Mathematics | Prove that 509,203 is the smallest Riesel number by finding a prime of the form k × 2n − 1 for all odd k smaller than 509,203 | |||||

| SAT@home | 8 papers[101] | 2011-09 | No | Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences | Mathematics | Solve discrete problems by reducing them to the problem of satisfiability of Boolean formulas | ||

| SETI@home | 12 papers[102] | 1999-05-17 | 1,808,938 volunteers[103] | Windows, Linux, macOS, Android[104] | GPU CPU | University of California, Berkeley | Astronomy | Analyzing radio frequencies from space to search for extraterrestrial life. Sub project: Astropulse |

| SETI@home beta | see above | 2006-01-12 | GPU CPU | University of California, Berkeley | Software testing | Test project for SETI@home | ||

| SIMAP | 5 papers[105] | 2006-04-26 | No | University of Vienna | Molecular biology | Investigated protein similarities | ||

| SLinCA@Home | 2010-09-14 | No | National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine | Physics | Research in physics and materials science | |||

| Spinhenge@home | 3 papers[106] | No | Technion – Israel Institute of Technology | genetic linkage | Used genetic linkage analysis to find disease resistant genes | |||

| TANPAKU | 2 papers[107] | 2005-08-02[108] | No | Tokyo University of Science | Molecular biology | Protein structure prediction using the Brownian dynamics method | ||

| The Lattice Project | 16 papers[109] | 2004-06-30[110] | No | University of Maryland, College Park | Life science | Multiple applications | ||

| theSkyNet | 3 papers[111] | 2011-09-13 | No | International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research | Astronomy | Analysis of radio astronomy data from telescopes |

See also

[edit]- List of volunteer computing projects

- List of free and open-source Android applications

- List of grid computing projects

- List of citizen science projects

- List of crowdsourcing projects

- 3G Bridge

- Africa@home

- Citizen Cyberscience Centre

- distributed.net

- Folding@home

- Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search

- grid.org

- Gridcoin

- BOSSA

References

[edit]- ^ "BOINC License". GitHub. Archived from the original on 2021-01-10. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ^ Anderson, David P. (2020-03-01). "BOINC: A Platform for Volunteer Computing". Journal of Grid Computing. 18 (1): 99–122. arXiv:1903.01699. doi:10.1007/s10723-019-09497-9. ISSN 1572-9184. S2CID 67877103.

- ^ Gonzalez, Laura Lynn, ed. (7 January 2007). "Rosetta@home". YouTube. Rosetta@home. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "Save the world using your PC or phone". CNET. Archived from the original on 2017-05-20. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ^ Scoles, Sarah. "A Brief History of SETI@Home". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2017-05-23. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ^ "Projects - BOINC Projects". boincsynergy.ca. Archived from the original on 2022-08-28. Retrieved 2022-08-29.

- ^ "BOINC computing power". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-11-16. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

- ^ "TOP500 List - November 2021 | TOP500". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 2022-04-08. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

- ^ Research and Infrastructure Development for Public-Resource Scientific Computing Archived 2021-01-19 at the Wayback Machine, The National Science Foundation

- ^ SCI: NMI Development for Public-Resource Computing and Storage Archived 2004-11-10 at the Wayback Machine, The National Science Foundation

- ^ SDCI NMI Improvement: Middleware for Volunteer Computing Archived 2009-05-12 at the Wayback Machine, The National Science Foundation

- ^ "Largest computing grid". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- ^ "Put your Android device to work on World Community Grid!". July 22, 2013. Archived from the original on October 9, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ "Manual sites of FreeBSD system". January 2, 2015. Archived from the original on January 17, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ The Name and Logo, by David P. Anderson, at Continuum-Hypothesis.com; published January 15, 2022; retrieved June 5, 2024

- ^ Anderson, David P. (November 2003). "Public Computing: Reconnecting People to Science". Archived from the original on 2007-05-15. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Karimi, Kamran; Dickson, Neil; Hamze, Firas (2010). "High-Performance Physics Simulations Using Multi-Core CPUs and GPGPUs in a Volunteer Computing Context". International Journal of High Performance Computing Applications. 25: 61–69. arXiv:1004.0023. Bibcode:2010arXiv1004.0023K. doi:10.1177/1094342010372928. S2CID 14214535.

- ^ "Choosing BOINC projects". BOINC. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ "2021 BOINC Workshop". 2021 BOINC Workshop. Archived from the original on 2021-09-14. Retrieved 2021-09-14.

- ^ "GPU computing - BOINC". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-08-03. Retrieved 2021-09-14.

- ^ "Android FAQ". BOINC. UC Berkeley. 12 April 2018. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ^ a b "Projects". BOINC. Archived from the original on 2011-03-20. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- ^ Anderson, David P. (September 2021). "Globally Scheduling Volunteer Computing". Future Internet. 13 (9): 229. doi:10.3390/fi13090229. ISSN 1999-5903.

- ^ "Choosing BOINC projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-01-03. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2024-12-22. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

- ^ "Project status". www.cpdn.org. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Applications". www.cpdn.org. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2024-12-22. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

- ^ "Einstein@Home server status page". einsteinathome.org. Archived from the original on 2022-08-22. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Applications". einsteinathome.org. Archived from the original on 2022-08-22. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2024-12-22. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

- ^ "Server status". gerasim.boinc.ru. Archived from the original on 2022-09-01. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ^ "Project application". gerasim.boinc.ru. Archived from the original on 2022-09-01. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2024-12-22. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

- ^ "Project status". www.gpugrid.net. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Applications". www.gpugrid.net. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2025-08-24. Retrieved 2025-08-30.

- ^ Swierczewski, Lukasz (2025-04-16). "Structural Resilience Analysis of an Internet Fragment Against Targeted and Random Attacks -- A Case Study Based on iThena Project Data". arXiv:2504.17796 [cs.NI].

- ^ "Project status". root.ithena.net. Archived from the original on 2025-08-22. Retrieved 2025-08-30.

- ^ "Project status". comp.ithena.net. Archived from the original on 2025-08-22. Retrieved 2025-08-30.

- ^ "Applications". root.ithena.net. Archived from the original on 2025-08-23. Retrieved 2025-08-30.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2024-12-22. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

- ^ "Project status". lhcathome.cern.ch. Archived from the original on 2022-08-08. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Applications". lhcathome.cern.ch. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2024-12-22. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

- ^ "Project status". milkyway.cs.rpi.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-03-06. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Applications". milkyway.cs.rpi.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-03-06. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2024-12-22. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

- ^ "Server status page". www.primegrid.com. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Applications". www.primegrid.com. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Project status". ralph.bakerlab.org. Archived from the original on 2022-11-04. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- ^ "Applications". ralph.bakerlab.org. Archived from the original on 2022-11-04. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2024-12-22. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

- ^ "Project status". boinc.bakerlab.org. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Applications". boinc.bakerlab.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-14. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2024-12-22. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

- ^ "Project status". gene.disi.unitn.it. Archived from the original on 2022-09-11. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ "Applications". gene.disi.unitn.it. Archived from the original on 2022-09-11. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2024-12-22. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

- ^ "BOINC stats - World Community Grid". www.boincstats.com. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Choosing BOINC projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-01-03. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2024-12-22. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

- ^ "Detailed stats - yoyo@home". www.boincstats.com. Archived from the original on 2022-09-01. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ^ "Applications". www.rechenkraft.net. Archived from the original on 2022-07-24. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ^ Martin, Greg; Miao, Winnie (2014-09-10). "abc triples". arXiv:1409.2974 [math.NT].

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ Barina, David (2021-03-01). "Convergence verification of the Collatz problem". The Journal of Supercomputing. 77 (3): 2681–2688. doi:10.1007/s11227-020-03368-x. ISSN 1573-0484. S2CID 220294340. Archived from the original on 2020-08-05. Retrieved 2022-10-01.

- ^ Cruncher Pete (2011-09-02). "Information on Collatz Conjecture". Archived from the original on 2013-12-26. Retrieved 2012-02-03.

- ^ "BOINC | BOINC Combined Statistics". boinc.netsoft-online.com. Archived from the original on 2022-09-10. Retrieved 2022-09-10.

- ^ "Applications". 2019-02-05. Archived from the original on 2019-02-05. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ^ "Collatz Conjecture". 2012. Archived from the original on 2017-12-04. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Correlizer". www.boincstats.com. Archived from the original on 2022-09-10. Retrieved 2022-09-10.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Project status". www.cosmologyathome.org. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Applications". www.cosmologyathome.org. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Docking@Home Project News". docking.cis.udel.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-11-18. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". Archived from the original on 2022-12-30. Retrieved 2022-12-30.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". Archived from the original on 2022-12-30. Retrieved 2022-12-30.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2024-12-22. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

- ^ "Project status". 2021-04-21. Archived from the original on 2021-04-21. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Applications". 2019-07-13. Archived from the original on 2019-07-13. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ Swierczewski, Lukasz (2012-10-04). "The Distributed Computing Model Based on The Capabilities of The Internet". arXiv:1210.1593 [cs.NI].

- ^ Tricarico, Pasquale (2017-03-01). "The near-Earth asteroid population from two decades of observations". Icarus. 284: 416–423. arXiv:1604.06328. Bibcode:2017Icar..284..416T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.12.008. ISSN 0019-1035. S2CID 85440139.

- ^ "Pirates@Home". 2005-03-14. Archived from the original on 2005-03-14. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ "I2U2". i2u2.spy-hill.net. Archived from the original on 2018-12-19. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "CASP6 Home page". 2004-06-03. Archived from the original on 2004-06-03. Retrieved 2022-08-16.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Detailed stats SETI@Home". www.boincstats.com. Archived from the original on 2022-09-30. Retrieved 2022-09-30.

- ^ "Applications". setiathome.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-10-05. Retrieved 2022-09-30.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "News archive". 2006-06-16. Archived from the original on 2006-06-16. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "The Lattice Project". 2004-08-28. Archived from the original on 2004-08-28. Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- ^ "Publications by BOINC Projects". boinc.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24.