Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Zenith

View on Wikipedia

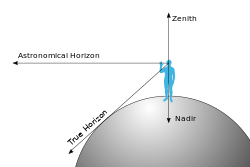

The zenith (UK: /ˈzɛnɪθ/, US: /ˈziː-/)[1][2] is the imaginary point on the celestial sphere directly "above" a particular location. "Above" means in the vertical direction (plumb line) opposite to the gravity direction at that location (nadir). The zenith is the "highest" point on the celestial sphere. The direction opposite of the zenith is the nadir.

Origin

[edit]The word zenith derives from an inaccurate reading of the Arabic expression سمت الرأس (samt al-raʾs), meaning "direction of the head" or "path above the head", by Medieval Latin scribes in the Middle Ages (during the 14th century), possibly through Old Spanish.[3] It was reduced to samt ("direction") and miswritten as senit/cenit, the m being misread as ni. Through the Old French cenith, zenith first appeared in the 17th century.[4]

Relevance and use

[edit]

The term zenith sometimes means the highest point, way, or level reached by a celestial body on its daily apparent path around a given point of observation.[5] This sense of the word is often used to describe the position of the Sun ("The sun reached its zenith..."), but to an astronomer, the Sun does not have its own zenith and is at the zenith only if it is directly overhead.

In a scientific context, the zenith is the direction of reference for measuring the zenith angle (or zenith angular distance), the angle between a direction of interest (e.g. a star) and the local zenith - that is, the complement of the altitude angle (or elevation angle).

The Sun reaches the observer's zenith when it is 90° above the horizon, and this only happens between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. The point where this occurs is known as the subsolar point. In Islamic astronomy, the passing of the Sun over the zenith of Mecca becomes the basis of the qibla observation by shadows twice a year on 27/28 May and 15/16 July.[6][7]

At a given location during the course of a day, the Sun reaches not only its zenith but also its nadir, at the antipode of that location 12 hours from solar noon.

In astronomy, the altitude in the horizontal coordinate system and the zenith angle are complementary angles, with the horizon perpendicular to the zenith. The astronomical meridian is also determined by the zenith, and is defined as a circle on the celestial sphere that passes through the zenith, nadir, and the celestial poles.

A zenith telescope is a type of telescope designed to point straight up at or near the zenith, and used for precision measurement of star positions, to simplify telescope construction, or both. The NASA Orbital Debris Observatory and the Large Zenith Telescope are both zenith telescopes, since the use of liquid mirrors meant these telescopes could only point straight up.

On the International Space Station, zenith and nadir are used instead of up and down, referring to directions within and around the station, relative to the earth.

Zenith star

[edit]Zenith stars (also "star on top", "overhead star", "latitude star")[8] are stars whose declination equals the latitude of the observers location, and hence at some time in the day or night pass culminate (pass) through the zenith. When at the zenith the right ascension of the star equals the local sidereal time at your location. In celestial navigation this allows latitude to be determined, since the declination of the star equals the latitude of the observer. If the current time at Greenwich is known at the time of the observation, the observers longitude can also be determined from the right ascension of the star. Hence "Zenith stars" lie on or near the circle of declination equal to the latitude of the observer ("zenith circle"). Zenith stars are not to be confused with "steering stars"[8] of a sidereal compass rose of a sidereal compass.

See also

[edit]![]() Media related to Zenith (topography) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Zenith (topography) at Wikimedia Commons

References

[edit]- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Corominas, J. (1987). Breve diccionario etimológico de la lengua castellana (in Spanish) (3rd ed.). Madrid. p. 144. ISBN 978-8-42492-364-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "zenith". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

- ^ "Zenith". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ van Gent, Robert Harry (2017). "Determining the Sacred Direction of Islam". Webpages on the History of Astronomy.

- ^ Khalid, Tuqa (2016). "Sun will align directly over Kaaba, Islam's holiest shrine, on Friday". CNN.

- ^ a b Lewis, David (1972). "We, the navigators : the ancient art of landfinding in the Pacific". Australian National University Press. Retrieved 2023-06-01.

Further reading

[edit]- Glickman, Todd S. (2000). Glossary of meteorology. American Meteorological Society. ISBN 978-1-878220-34-9.

- McIntosh, D. H. (1972). Meteorological Glossary (5th ed.). Chemical. ISBN 978-0-8206-0228-8.

- Picoche, Jacqueline (2002). Dictionnaire étymologique du français. Paris: Le Robert. ISBN 978-2-85036-458-7.

Zenith

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Fundamentals

Etymology

The term "zenith" derives from the Arabic phrase samt ar-rās, meaning "path over the head" or "direction of the head," referring to the overhead point in the sky.[5] This phrase originated in medieval Islamic astronomical texts, where it described the vertical path above an observer.[6] The word entered European languages through translations of Arabic works during the Islamic Golden Age, reflecting the profound influence of Muslim scholars on Western astronomy; for instance, terms like zenith entered Latin via such transmissions, alongside concepts from astronomers like Al-Farghani (known in Latin as Alfraganus), whose 9th-century Elements of Astronomy was widely translated in Europe.[8] In Medieval Latin, the term appeared as cenit or zenit, often resulting from scribal misreadings of the Arabic script, where the letter m in samt was confused with ni.[5] It passed into Old French as cenith by the late 14th century before entering English in the late 14th century in its astronomical sense, initially through scholarly texts on celestial navigation and observation.[6] The word's adoption highlights the broader transmission of Islamic astronomical terminology to Europe, including related terms like azimuth and nadir.[8] Variations persist across modern languages, such as French zénith (with an acute accent on the e) and Italian zenit, maintaining the core pronunciation while adapting to local phonetics.[5]Definition

In astronomy, the zenith is defined as the point on the celestial sphere directly overhead an observer, representing the intersection of an upward vertical line—perpendicular to the local horizon plane—with the imaginary dome of the sky.[2] This point lies at an altitude of 90° above the horizon and is diametrically opposite the nadir, the corresponding point directly beneath the observer.[9] The zenith thus marks the highest point in the observer's local sky, serving as a fundamental reference in celestial coordinate systems. Geometrically, the zenith aligns with an imaginary line passing from the observer straight upward through the Earth's center and extending to the nadir on the far side of the planet, emphasizing its role as the apex of the local vertical axis.[10] This configuration assumes a spherical Earth model and ignores minor local gravitational variations that might slightly deflect the plumb line defining "up."[3] A distinction exists between the astronomical zenith, defined by the local direction of gravity (plumb line), and the geocentric zenith, defined by the radial line from Earth's center through the observer. Local mass irregularities, such as mountains, can cause slight deflections (up to arcminutes) between these directions, except at the equator and poles where they coincide due to symmetry.[3] Atmospheric refraction affects the apparent positions of celestial objects near the zenith minimally, as the effect decreases to zero at the zenith itself, but corrections are applied in precise measurements.[11]Celestial Geometry

Position on the Celestial Sphere

The celestial sphere is conceptualized as an imaginary sphere of infinite radius centered on the Earth, serving as a projection surface onto which the positions of stars and other celestial objects are mapped to simplify astronomical observations.[12] Within this framework, the zenith represents the point on the sphere directly overhead an observer, defined by the local vertical direction perpendicular to the Earth's surface at that location. This positions the zenith as the north pole of the observer's personal horizon system, analogous to how the north celestial pole functions in the equatorial coordinate system. The horizon coordinate system, or alt-azimuth system, uses the observer's local horizon as its fundamental plane and the zenith as its upper pole to describe celestial positions.[13] In this system, any point on the celestial sphere is located using two coordinates: altitude, which measures the angular height above the horizon (ranging from 0° at the horizon to 90° at the zenith), and azimuth, which measures the horizontal direction clockwise from true north along the horizon (ranging from 0° to 360°).[14] At the zenith itself, the altitude is exactly 90°, but the azimuth becomes undefined, as the point lies at the convergence of all horizontal directions, similar to how longitude is undefined at the Earth's geographic poles.[15] Earth's rotation on its axis, completing one full turn approximately every 24 hours, causes the apparent motion of the celestial sphere relative to the observer.[16] From the perspective of fixed stars (which define an inertial reference frame), the zenith's direction in space shifts continuously westward, tracing a daily path on the celestial sphere that parallels the celestial equator at an angular distance equal to the observer's latitude.[17] Consequently, different stars pass through the zenith over the course of a sidereal day, altering which celestial objects appear directly overhead at any given time.[18]Relation to Nadir and Horizon Coordinates

In the horizon coordinate system, the nadir serves as the antipodal point to the zenith, located directly below the observer at the opposite end of the local vertical axis. This positions the nadir 180° away from the zenith along the plumb line, forming a straight line that passes through the observer and the center of the Earth, assuming a spherical model.[1][3] The horizon, in turn, is defined as the great circle on the celestial sphere that lies precisely 90° from both the zenith and the nadir, perpendicular to the local vertical axis through the observer. This configuration places the horizon at an altitude of 0°, serving as the fundamental reference for measuring elevations above or below it in the alt-azimuth system.[13][19] Within this framework, azimuth circles—also known as vertical circles or hour circles in the local system—function as meridians connecting the zenith to the nadir, each representing a great circle path along which altitude is measured for celestial objects. These circles are oriented by azimuth angles, typically measured clockwise from true north (or sometimes south in southern hemisphere conventions) along the horizon to the point where the circle intersects it, enabling precise localization in the horizon-based coordinate system used in observational astronomy.[3][20]Measurement and Properties

Zenith Distance

The zenith distance (ZD) of a celestial object is the angular separation between the object's position on the celestial sphere and the observer's zenith, measured along the great circle that passes through both points.[21] This measurement is fundamental in horizon-based coordinate systems, where it directly relates to the object's altitude above the horizon.[22] The zenith distance is calculated using the formulawhere is the altitude of the object.[21] This relation holds because the zenith is at 90° altitude, making ZD the complement of the altitude angle.[23] In astronomical observations, zenith distance plays a key role in applying corrections for atmospheric refraction, which bends light rays and alters apparent positions. Refraction is minimal at the zenith (ZD = 0°) but increases toward the horizon, and standard refraction tables are typically indexed by ZD for precise adjustments up to about 45° or more.[24] For instance, formulas for refraction across all zenith distances incorporate terms that depend on ZD to account for varying atmospheric density effects.[25] As an example, if a star is observed at an altitude of 30°, its zenith distance is 60°, requiring a corresponding refraction correction from tables to determine the true position.[21] Historically, zenith distance computations from sextant-measured altitudes were essential for latitude determination in celestial navigation, as detailed in standard texts like The American Practical Navigator.