Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

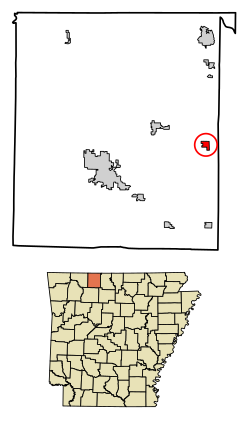

Zinc, Arkansas

View on Wikipedia

Zinc is a town near the east-central edge of Boone County, Arkansas, United States. The population was 92 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Harrison Micropolitan Statistical Area. A chapter of the Ku Klux Klan operates in Zinc.[3]

Key Information

History

[edit]

Zinc mining in the area gave the town its name.[4] Zinc and lead mining began in the 1890s and peaked during World War I (1914–1918). A post office was established in Zinc in 1900 and the town was incorporated in 1904.[5]

The town had a number of business establishments and a school in the 1920s, but a flood in 1927 caused damage to homes and businesses. Zinc's population was 188 in 1930 and declined thereafter. The last store closed in Zinc in the late 1960s and the post office closed in 1975.[5]

Zinc, in the 21st century, became the headquarters of a chapter of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK),[5] classified as a hate group by the Anti-Defamation League[6] and the Southern Poverty Law Center.[7] The "Christian Revival Center" near Zinc belongs to a preacher named Thomas Robb who is also the leader of the Knights of the KKK. The center hosts events connected with the KKK, including in 2013 a "Klan Kamp" called the "Soldiers of the Cross Training Institute" to instill "the tools to become actively involved" in the "struggle for our racial redemption".[8]

Other activities of the KKK near Zinc include the placement of signs along highways with messages such as "Diversity is a code for #whitegenocide".[9]

In May 2022, English YouTuber Niko Omilana published a video documenting his experiences in Zinc and Harrison while disguised as a journalist for the BBC. The video includes an interview with Thomas Robb, where he unwittingly shouts out fake Instagram users whose names phoneticize phrases such as "BLM".[10]

National Historic Sites

[edit]

Two National Historic Sites are located in the town: the Elliott and Anna Barham House and the Zinc Swinging Bridge.

Geography

[edit]Zinc is located at 36°17′7″N 92°54′56″W / 36.28528°N 92.91556°W (36.285384, −92.915419), approximately nine miles east in straight-line distance from the county seat of Harrison.[11] According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 0.752 square miles (1.95 km2), of which 0.751 square miles (1.95 km2) is land and 0.001 square miles (0.0026 km2) is water.[12]

Zinc is in the Ozark region and has an elevation of 879 feet (268 m).[13]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 173 | — | |

| 1920 | 144 | −16.8% | |

| 1930 | 188 | 30.6% | |

| 1940 | 119 | −36.7% | |

| 1950 | 99 | −16.8% | |

| 1960 | 68 | −31.3% | |

| 1970 | 58 | −14.7% | |

| 1980 | 113 | 94.8% | |

| 1990 | 91 | −19.5% | |

| 2000 | 76 | −16.5% | |

| 2010 | 103 | 35.5% | |

| 2020 | 92 | −10.7% | |

| 2024 (est.) | 90 | −2.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

Demographics

[edit]As of the census[15] of 2010, there were 103 people, 37 households, and 23 families residing in the town. The population density was 39.1 people/km2 (101 people/mi2). There were 35 housing units at an average density of 18.0 units/km2 (47 units/mi2). The racial makeup of the town was 88.3% White, 1% Black or African American, and 8.7% from two or more races. 1.9% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 37 households, out of which 64.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.2% were married couples living together, 16.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 22.6% were non-families. 19.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 3.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 2.79.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 18.4% under the age of 18, 6.6% from 18 to 24, 25.0% from 25 to 44, 38.2% from 45 to 64, and 11.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 45 years. For every 100 females, there were 145.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 148.0 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $20,036, and the median income for a family was $18,250. Males had a median income of $10,194 versus $5,250 for females. The per capita income for the town was $9,999. There were 35.8% of families and 25.9% of the population living below the poverty line, including 43.0% of those under 18 and 63.7% of those over 65.

Zinc, along with Bergman, is within the Bergman School District.[16]

In popular culture

[edit]In 2022, American YouTuber Poudii came to Zinc to investigate claims that "Zinc is the most racist town in America". In his first visit, Poudii met and interviewed Tom Bowie, who is a Ku Klux Klan affiliate[better source needed] and commentator on the Neo-Nazi website Stormfront.[17] Clips of this interview gained fame both on YouTube and TikTok with comments raving about the meeting between the two.[4] Poudii returned to Zinc twice,[6] and the larger neighboring town of Harrison to interview more residents.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Zinc, Arkansas

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ "Thomas Robb". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ a b "Colorful Names". Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism. Archived from the original on November 24, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Zinc (Boone County)". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c "About the Ku Klux Klan". Anti-Defamation League. Archived from the original on October 3, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Ku Klux Klan". Southern Poverty Law Center.

- ^ "Thomas Robb". Southern Poverty Law Center.

- ^ Schulte, Bret (April 3, 2017). "The Alt-Right of the Ozarks". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ Browning, Oliver (May 16, 2022). "YouTuber pranks KKK leader into saying 'BLM' during fake BBC interview". The Independent. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.; Google Earth

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Google Earth

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ School District Reference Map (2010 Census): Boone County, AR (PDF) (Map). US Census Bureau. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- ^ "Meet the New Wave of Extremists Gearing up for the 2016 Elections".

External links

[edit]- Map of Zinc (US Census Bureau)

- Boone County Historical and Railroad Society, Inc.

- Bergman School District Archived July 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Town government information

- Detailed 2000 US Census statistics

- Boone County School District Reference Map (US Census Bureau, 2010)

Zinc, Arkansas

View on GrokipediaHistory

Founding and Zinc Mining Era

The community of Zinc in Boone County, Arkansas, traces its origins to the late 19th century, when zinc ore deposits were identified in the region as part of the northern Arkansas zinc belt. Elias Barham became the first documented settler, purchasing land in the area in 1890, though evidence suggests he may have occupied it earlier.[1] The settlement's name directly reflects these mineral resources, distinguishing it from agricultural or timber-based communities nearby.[1] Formal establishment of Zinc coincided with infrastructural developments that supported mining. The arrival of the St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad around 1900 enabled efficient ore shipment, spurring population influx and commercial activity. A post office opened in 1902, marking the town's administrative recognition. Zinc mining operations in Boone County commenced shortly thereafter, with the inaugural rail shipment of zinc ore from the nearby Almy Mine near Harrison occurring in fall 1901.[1][3] The zinc mining era in the Zinc area peaked during World War I, fueled by surging demand for the metal in munitions and galvanizing. Arkansas statewide zinc production reached its zenith in 1917, with northern counties including Boone contributing through small-to-medium shafts exploiting sphalerite veins in limestone formations. Local output supported regional totals, though individual mines around Zinc remained modest compared to larger sites like the Morning Star Mine in adjacent Marion County, discovered in 1880. By the 1920s, Zinc's population approached 200 residents, sustained by mining employment, ore processing, and ancillary services.[4][3][1]Post-Mining Decline and 20th Century Developments

Following the peak of zinc and lead mining during World War I, the industry in Zinc experienced a sharp decline due to plummeting ore prices in the postwar period and exacerbated by the Great Depression, leading to widespread mine closures and outmigration of workers.[1][3] By the 1920s, production in northern Arkansas, including Boone County, had significantly diminished as global supply exceeded demand, rendering many operations unprofitable.[3] The town's population reflected this economic contraction: it stood at 144 in 1920 but briefly rose to 188 by 1930 before falling to 119 in 1940, 99 in 1950, and continuing downward to 58 by 1970.[1] A major flood in 1927 devastated local infrastructure, prompting the construction of a swinging bridge over Sugar Orchard Creek, which was later added to the National Register of Historic Places (though it collapsed in 2014 and was restored in 2015).[1] Around 1927, the Zinc school district consolidated with the larger Bergman district, signaling reduced local viability.[1] In the 1930s, residents attempted diversification with a short-lived tomato cannery, but the economy increasingly relied on subsistence agriculture and remnant railroad activity rather than industry.[1] Commercial decline culminated in the closure of the last general store in the late 1960s and the post office in 1975, leaving Zinc as a quiet rural community with minimal services.[1] Despite these setbacks, the area's isolation preserved some historical structures, though the population stabilized at low levels, reaching 76 by 2000.[1]Recent History and Population Changes

Following the closure of local stores in the late 1960s and the discontinuation of the post office in 1975, Zinc experienced further erosion of community infrastructure, reflecting broader rural depopulation trends in post-mining areas of northern Arkansas.[1] The Missouri Pacific Railroad maintained service through the town into the late 20th century, providing limited connectivity, but economic stagnation persisted amid the absence of diversified industry.[1] In 2009, a Ku Klux Klan rally occurred in the vicinity of Zinc and nearby South Lead Hill, drawing approximately 50 participants, though no such events took place within Zinc proper.[1] A notable local incident in June 2014 involved the collapse of the historic swinging bridge over nearby Bear Creek, listed on the National Register of Historic Places; repairs were completed by 2015, restoring pedestrian access.[1] Beyond these episodes, Zinc has remained a quiet, unincorporated-like community with minimal documented public events or economic initiatives through 2025, underscoring its status as a small, stable rural enclave.[1] Population in Zinc has shown volatility since 1950, with an overall trend of small size and intermittent growth amid regional outmigration.| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 99 |

| 1960 | 68 |

| 1970 | 58 |

| 1980 | 113 |

| 1990 | 91 |

| 2000 | 76 |

| 2010 | 103 |

| 2020 | 92 |

Geography

Location and Physical Features

Zinc is situated in northwestern Boone County, in the northern part of Arkansas, United States, at approximate coordinates 36°17′07″N 92°54′50″W.[1] The town lies within the Ozark Plateau physiographic region, characterized by dissected uplands with elevations ranging from valleys to hilltops.[7] Its central elevation measures 879 feet (268 meters) above sea level.[1][8] The physical landscape surrounding Zinc features rolling hills, steep valleys, and karst topography influenced by soluble limestone bedrock, part of the Springfield Plateau subdivision of the Ozarks.[9] This terrain, with its uneven relief and occasional sinkholes, reflects the geological history of uplift and erosion in northern Arkansas.[4] The total land area of the incorporated town is 0.75 square miles, predominantly undeveloped or used for low-density residential and agricultural purposes.[1] Nearby water features include tributaries draining into the White River system, contributing to the area's hydrological patterns.[10]Climate and Environmental Factors

Zinc experiences a humid subtropical climate typical of the Ozark Mountains region, with hot, humid summers and cool winters. Average annual temperatures range from a low of 29°F in January to a high of 89°F in July, with an overall yearly average of 61.7°F.[11][12] The area receives approximately 46 to 48 inches of precipitation annually, predominantly as rain, with about 8 inches of snowfall concentrated in winter months.[13][12] Summers feature frequent thunderstorms, contributing to the high rainfall totals, while winters are mild but can include occasional ice storms and freezing temperatures. The growing season spans roughly 200 days, supporting agriculture and forestry, though the region is susceptible to severe weather events such as tornadoes and flash flooding due to its hilly terrain and karst hydrology.[11] Environmentally, Zinc is situated in the Springfield Plateau of the Ozark Plateaus physiographic province, characterized by karst topography with limestone bedrock that promotes sinkholes, caves, and rapid groundwater infiltration, increasing vulnerability to contamination.[14] Historical zinc and lead mining operations in northern Arkansas, including deposits in Boone County, have left abandoned mines and tailings that contribute to localized heavy metal concentrations in soils and potential leaching into aquifers via acid mine drainage.[2][15] These legacy effects from early 20th-century extraction activities necessitate ongoing monitoring of water quality, as zinc and associated metals can persist in the environment from mining disturbances.[16]Demographics

Population Statistics and Trends

The population of Zinc peaked at 188 during the 1930 United States Census, coinciding with the height of local zinc mining activity.[1] Following the closure of mines after World War I and during the Great Depression, the town's population declined sharply, reaching a low of 58 by the 1970 Census, as residents sought employment elsewhere amid the collapse of the mining-based economy.[1] Subsequent decades showed fluctuations, with a modest rebound to 113 in 1980 possibly linked to broader rural migration patterns in Boone County, before stabilizing in the 90-100 range.[1] The 2010 Census recorded 103 residents, decreasing slightly to 92 by 2020, reflecting ongoing challenges in rural Arkansas communities such as outmigration and limited economic diversification.| Census Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1910 | 173 |

| 1920 | 144 |

| 1930 | 188 |

| 1940 | 119 |

| 1950 | 99 |

| 1960 | 68 |

| 1970 | 58 |

| 1980 | 113 |

| 1990 | 91 |

| 2000 | 76 |

| 2010 | 103 |

| 2020 | 92 |

Socioeconomic Characteristics

The median household income in Zinc was estimated at $34,375 in 2023, well below the Arkansas statewide median of $58,773, reflecting the economic challenges of a small rural town with limited industry following the decline of zinc mining.[5][18] Per capita income was reported at $17,222 the same year, underscoring persistent low earnings amid a population of approximately 60 residents.[19] The poverty rate stood at 20%, higher than the state average of around 15.9%, with these figures derived from American Community Survey (ACS) data that carries substantial margins of error due to the town's small size, potentially leading to suppressed or aggregated reporting in official Census Bureau tables.[20][21] Educational attainment in Zinc lags behind state norms, with approximately 20% of adults lacking a high school diploma or equivalent, compared to Arkansas's 12.6% rate, while about 44% hold a high school diploma as their highest qualification and roughly 31% have some postsecondary education.[18] These estimates, again from ACS 5-year data, highlight barriers to higher education in isolated rural areas, where access to institutions is limited and workforce demands historically favored manual labor over advanced degrees. Employment patterns align with broader Boone County trends, emphasizing agriculture, construction, and retail trade, though specific town-level unemployment data is unavailable due to sample size constraints; state-level rural unemployment hovered around 3.8% in recent years, but underemployment remains a concern in former mining communities like Zinc.[22] Homeownership rates are high, indicative of generational land ties in rural Arkansas, but housing values are modest, averaging under $100,000, which correlates with limited wealth accumulation and vulnerability to economic shocks.[23] Overall, Zinc's socioeconomic profile embodies the structural disadvantages of depopulated, post-extractive rural locales, where federal assistance programs and commuting to nearby Harrison provide partial mitigation, yet systemic factors like geographic isolation perpetuate income disparities.[5]Racial and Ethnic Composition

According to the 2020 United States Census, Zinc had a population of 92 residents.[5] The racial and ethnic composition was overwhelmingly White, reflecting the town's rural character in northern Arkansas.[23] White individuals of non-Hispanic origin constituted 90% of the population (approximately 83 persons), comprising the dominant group.[5] Hispanic or Latino residents, primarily identified under "Other (Hispanic)" race, accounted for 6.67% (about 6 persons), marking the largest minority ethnic segment.[5] Individuals identifying with two or more races (non-Hispanic) made up 3.33% (around 3 persons), while all other racial categories—such as Black, Asian, Native American, or Pacific Islander—were negligible or zero.[5][24]| Race/Ethnicity | Percentage | Approximate Number (2020 pop. 92) |

|---|---|---|

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 90% | 83 |

| Hispanic or Latino (Other race) | 6.67% | 6 |

| Two or More Races (Non-Hispanic) | 3.33% | 3 |

| All Others | 0% | 0 |