Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

AMOS-6 (satellite)

View on Wikipedia

| Names | Affordable Modular Optimized Satellite-6 |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Communications |

| Operator | Spacecom Satellite Communications |

| Mission duration | 15 years (planned) [1] Failed to orbit (achieved) |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Bus | AMOS 4000[2] |

| Manufacturer | Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) |

| Launch mass | 5,500 kg (12,100 lb) [3] |

| Power | 10 kW[2] |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 3 September 2016 (planned) |

| Rocket | Falcon 9 Full Thrust |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral, SLC-40 |

| Contractor | SpaceX |

| Entered service | Destroyed before launch |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Fire in failed launch test |

| Destroyed | 1 September 2016, 13:07 UTC[4] |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric orbit |

| Regime | Geostationary orbit |

| Longitude | 4° West |

| Transponders | |

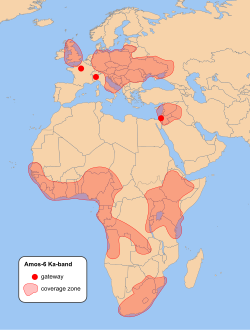

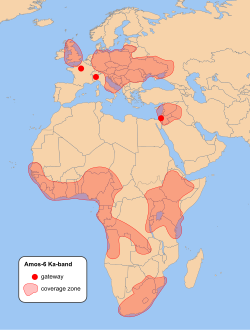

| Band | Ku-band, 36 Ka-band, 2 S-band transponders |

| Coverage area | Israel, Europe, Africa, Asia, Middle East |

AMOS-6 was an Israeli communications satellite, one of the Spacecom AMOS series, that was built by Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI), a defense and aerospace company.[5]

AMOS-6 was intended to be launched on flight 29 of a SpaceX Falcon 9 to geostationary transfer orbit (GTO) on 3 September 2016. On 1 September 2016, during the run-up to a static fire test, there was an anomaly on the launch pad, resulting in an explosion and the loss of the vehicle and AMOS-6. There were no injuries.[4]

Terminology

[edit]AMOS stands for "Affordable Modular Optimized Satellite" [5] and is also an allusion to the prophet Amos. This spacecraft is the second implementation of the AMOS-4000 satellite bus, the first was the AMOS-4. It is one of a AMOS series of satellites built by Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI).

History

[edit]Spacecom, the AMOS satellites operator, announced in June 2012 that it had signed a US$195 million contract to build AMOS-6, the newest addition to the AMOS constellation, with Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI). In January 2013, Spacecom announced that they had signed a contract with SpaceX for the 2015 launch of the AMOS-6 satellite on a Falcon 9 launch vehicle.[1] AMOS-6 was intended to replace the AMOS-2 satellite, planned to be retired in 2016.[6] During 2015 Spacecom announced the launch date had slipped to mid-2016.[1] A final launch date was set for 3 September 2016.

Under the deal with Spacecom, state-owned IAI was contracted to build AMOS-6 and its ground control systems, as well as provide operating services.[5] Spacecom estimated that the cost of launching, insuring and one year's operation of AMOS-6 would be US$85 million.[7]

The AMOS-6 included payload components from various sub-contractors including Canada's MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates, which built the communications payload, and Thales Alenia Space ETCA for the electric propulsion. The satellite "[incorporated] new technologies that represent a significant leap forward in the capabilities of IAI and the state of Israel in space", according to IAI's president.[5]

Lease to external customers

[edit]In October 2015, social media company Facebook and satellite fleet operator Eutelsat agreed to pay Spacecom US$95 million over a period of about five years for the lease of the Ka-band spot-beam broadband capacity — 36 regional spotbeams with a throughput of about 18 Gbit/s — on AMOS-6 to provide service for Facebook and a new Eutelsat subsidiary focusing on African businesses.[1] Costs would be divided in approximately equal shares between Eutelsat and Facebook.[8] The parties agreed to the right to terminate the contract if AMOS-6 and the ground gateways in France, Italy and Israel were not ready for service by 1 January 2017. The lease was for the use of the satellite until September 2021, with an option for a two-year extension at a reduced rate.[1][8] After a technical analysis, including an assessment of customer power requirements, Facebook and Eutelsat concluded that only 18 out of the 36 Ka-band spot beams could be used simultaneously without sacrificing user experience.[8]

Destruction

[edit]On 1 September 2016, during propellant loading for a routine test, the Falcon 9 launch vehicle suffered an anomaly that destroyed the vehicle and its AMOS-6 payload.[4] The explosion started near the upper stage LOX (liquid oxygen) tank. Because the satellite was destroyed prior to the launch, the cost of the satellite was not covered by Spacecom's insurance policy, but rather by the manufacturer, IAI.[9] IAI had its own insurance and filed a claim in order to compensate Spacecom. Spacecom's contract with SpaceX specified that Spacecom could choose to receive US$50 million, or a future flight at no cost.[10][11] Spacecom chose the future flight to launch AMOS-17.[12]

News reports in early November 2016 indicated that SpaceX had determined the root cause for the anomaly, that it was straightforwardly fixable, and that SpaceX would return to flight in December 2016.[13] On 2 January 2017, SpaceX released an official statement indicating that the cause of the failure was a buckled liner in several of the Composite overwrapped pressure vessel (COPV) tanks, causing perforations that allowed liquid and/or solid oxygen to accumulate between the liner and the overwrap, which was ignited by friction.[14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Facebook, Eutelsat To Pay Spacecom $95M for Ka-band Lease". SpaceNews. 6 October 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) has successfully launched Spacecom's AMOS-4". Israel Aerospace Industries. 31 August 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ "IAI Develops Small, Electric-Powered COMSAT". DefenseNews. 12 October 2015. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Malik, Tariq (1 September 2016). "Launchpad Explosion Destroys SpaceX Falcon 9 Rocket, Satellite in Florida". SPACE.com. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d "IAI to launch new 5-ton Amos satellite". spacedaily.com. Space Daily. UPI. 6 July 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Money, Stewart (30 January 2013). "SpaceX Wins New Commercial Launch Order". Innerspace. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Levy, Aviv (24 June 2012). "Spacecom to build $200m Amos-6 satellite". Globes. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "Facebook-Eutelsat Internet Deal Leaves Industry Awaiting Encore". SpaceNews. 9 October 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "IAI's announcement about loss of the communication satellite Amos 6". Israel Aerospace Industries. 4 September 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Cohen, Nitzan (4 September 2016). "Spacecom to claim Amos 6 compensation from IAI". Globes. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "Analysis: How SpaceX's spectacular pre-flight failure fueled a jump in hasty conclusions". SpaceNews. 6 September 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "Spacecom returns to SpaceX for one, possibly two launches". 18 October 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "Inmarsat, juggling two launches, says SpaceX to return to flight in December". SpaceNews. 3 November 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "January 2 Anomaly Updates". 2 January 2017. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2021.