Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ripuarian language

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (July 2023) |

| Ripuarian | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Germany, Belgium, Netherlands |

| Region | North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate, Liège Province, Limburg |

Native speakers | (Kölsch: 250,000 cited 1997)[1] |

Early forms | Proto-Indo-European

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis)Individual code: ksh – Kölsch |

| Glottolog | ripu1236 |

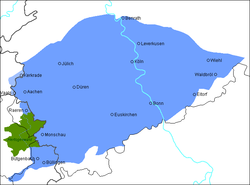

Area where Ripuarian is spoken. Green = sparsely populated forest. | |

Central German language area after 1945 and the expulsion of the Germans from the east. 1 = Ripuarian. | |

Ripuarian (/ˌrɪpjuˈɛəriən/ RIP-yoo-AIR-ee-ən) or Ripuarian Franconian[a] is a German dialect group, part of the West Central German language group. Together with the Moselle Franconian which includes the Luxembourgish language, Ripuarian belongs to the larger Central Franconian dialect family and also to the linguistic continuum with the Low Franconian languages.

It is spoken in the Rhineland south of the Benrath line — from northwest of Düsseldorf and Cologne to Aachen in the west and to Waldbröl in the east.

The language area also comprises the north of the German-speaking Community of Belgium as well as the southern edge of the Limburg province of the Netherlands, especially Kerkrade (Kirchroa), where it is perceived as a variety of Limburgish and legally treated as such.[citation needed]

The name derives from the Ripuarian Franks (Rheinfranken), who settled in the area from the 4th century onward.

The most well known Ripuarian dialect is Kölsch, the local dialect of Cologne. Dialects belonging to the Ripuarian group almost always call themselves Platt (spelled plat in the Netherlands) like Öcher Platt (of Aachen), Bönnsch Platt (of Bonn), Eischwiele Platt (of Eschweiler), Kirchröadsj plat (of Kerkrade), or Bocheser plat (of Bocholtz). Most of the more than one hundred Ripuarian dialects are bound to one specific village or municipality. Usually there are small distinctive differences between neighbouring dialects (which are, however, easily noticeable to locals), and increasingly bigger differences between the more distant dialects. These are described by a set of isoglosses called the Rhenish fan in linguistics. The way people talk, even if they are not using Ripuarian, often allows them to be traced precisely to a village or city quarter where they learned to speak.

Number of speakers

[edit]About a million people speak a variation of Ripuarian dialect, which constitutes about one quarter of the inhabitants of the area. Penetration of Ripuarian in everyday communication varies considerably, as does the percentage of Ripuarian speakers from one place to another. In some places there may only be a few elderly speakers left, while elsewhere Ripuarian usage is common in everyday life. Both in the genuine Ripuarian area and far around it, the number of people passively understanding Ripuarian to some extent exceeds the number of active speakers by far.

Geographic significance

[edit]Speakers are centred on the German city of Köln (Cologne). The language's distribution starts from the important geographic transition into the flat-lands coming down from the Middle Rhine. The Ripuarian varieties are related to the Moselle Franconian languages spoken in the southern Rhineland (Rhineland-Palatinate and Saarland) in Germany, to the Luxembourgish language in Luxembourg, and to the Low Franconian Limburgish language in the Dutch province of Limburg. Most of the historic roots of Ripuarian languages are in Middle German, but there were other influences too, such as Latin, Low German, Dutch, French and Southern Meuse-Rhenish (Limburgish). Several elements of grammar are unique to Ripuarian and do not exist in the other languages of Germany.[citation needed]

The French Community of Belgium as well as the Netherlands officially recognise some Ripuarian dialects as minority languages, and the European Union likewise follows.[citation needed]

Varieties

[edit]Varieties are or include:[2]

- West Ripuarian (Westripuarisch), around Aachen and a small area in East Belgium and the Netherlands

- Central Ripuarian (Zentralripuarisch)

- City Colognian (Stadtkölnisch)

- Country Colognian (Landkölnisch)

Grammar

[edit]Numerals

[edit]The transcription from Münch,[3] in which the grave accent (`) and macron (¯) represent, respectively, accent 1 and 2 in the Central/Low Franconian pitch accent.

The rest of the letters match their IPA/ German alphabet pronunciation, with a few exceptions:

| Cardinals | Ordinals | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ēn | dę ìəštə |

| 2 | tswęī | dę tswę̀itə |

| 3 | dreī | dę drę̀itə |

| 4 | fiəꝛ | dę fiətə |

| 5 | fønəf | dę fønəftə |

| 6 | zęks | dę zękstə |

| 7 | zevə | dę zevəntə |

| 8 | āx | dę āxtə |

| 9 | nøŋ̀ | dę nøŋ̄tə |

| 10 | tsèn | dę tsèntə |

| 11 | eləf | dę eləftə |

| 12 | tsweləf | dę tsweləftə |

| 13 | drøksēn | dę drøksēntə |

| 14 | fiətsēn | dę fiətsēntə |

| 15 | fuftsēn | dę fuftsēntə |

| 16 | zęksēn | dę zęksēntə |

| 17 | zevətsēn | dę zevetsēntə |

| 18 | āxtsēn | dę āxtsēntə |

| 19 | nøŋ̄sēn | dę nøŋ̄tsēntə |

| 20 | tswantsiχ | dę tswantsiχstə |

| 21 | enəntswantsiχ | |

| 22 | tswęiəntswantsiχ | |

| 23 | dreiəntswantsiχ | |

| 24 | fiəꝛentswantsiχ | |

| 25 | fønəvəntswantsiχ | |

| 26 | zękzəntswantsiχ | |

| 27 | zevənəntswantsiχ | |

| 28 | āxəntswantsiχ | |

| 29 | nøŋəntswantsiχ | |

| 30 | dresiχ | dę dresiχstə |

| 40 | fiətsiχ | dę fiətsiχstə |

| 50 | fuftsiχ | dę fuftsiχstə |

| 60 | zęksiχ | dę zęksiχstə |

| 70 | zevəntsiχ | dę zevətsiχstə |

| 80 | āxtsiχ | dę āxtsiχstə |

| 90 | nøŋ̄siχ | dę nøŋ̄tsiχstə |

| 100 | hondəꝛt | dę hondəꝛtstə |

| 200 | tsweīhondəꝛt | |

| 1000 | dùzənt | dę dùzəntstə |

Pronouns

[edit]Ripuarian (excluding City-Colognian) emphasised personal pronouns:[3]

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person m. / f. / n. |

reflexive pronoun (of the 3rd person) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | ||||||

| Nom. | iχ | du | hę̄ | zeī | ət | |

| Gen. | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Dat. | mīꝛ | dīꝛ | em̀ | ìꝛ | em̀ | ziχ |

| Acc. | miχ | diχ | en | zeī | ət | ziχ |

| Plural | ||||||

| Nom. | mīꝛ | īꝛ | zē | |||

| Gen. | – | – | – | |||

| Dat. | os | yχ | eǹə | ziχ | ||

| Acc. | os | yχ | zē | ziχ | ||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ German: Ripuarisch [ʁipuˈ(ʔ)aːʁɪʃ] ⓘ, ripuarische Mundart, ripuarischer Dialekt, ripuarisch-fränkische Mundart or Ribuarisch; Dutch: ripuarisch [ripyˈʋaːris] ⓘ or noordmiddelfrankisch.

References

[edit]- ^ Ripuarian at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

Kölsch at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ Jürgen Erich Schmidt, Robert Möller, Historisches Westdeutsch/Rheinisch (Moselfränkisch, Ripuarisch, Südniederfränkisch), sub-chapter Das Ripuarische; in: Sprache und Raum: Ein internationales Handbuch der Sprachvariation. Band 4: Deutsch. Herausgegeben von Joachim Herrgen, Jürgen Erich Schmidt. Unter Mitarbeit von Hanna Fischer und Birgitte Ganswindt, volume 30.4 of Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft (Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science / Manuels de linguistique et des sciences de communication) (HSK), Berlin/Boston, 2019, p. 529f.

- ^ a b Grammatik der ripuarisch-fränkischen Mundart von Ferdinand Münch. Bonn, 1904, p. 8ff. & p. 159f.

Some symbols with their IPA equivalent are:

Literature

[edit]- Hans Bruchhausen und Heinz Feldhoff: Us Platt kalle un verstonn - Mundartwörterbuch Lützenkirchen-Quettingen. Bergisch Gladbach 2005. ISBN 3-87314-410-7

- Leo Lammert und Paul Schmidt: Neunkirchen-Seelscheider Sprachschatz, herausgegeben vom Heimat- und Geschichtsverein Neunkirchen-Seelscheid 2006. (ca. 7300 Wörter)

- Manfred Konrads: Wörter und Sachen im Wildenburger Ländchen, Rheinland-Verlag, Köln, 1981

- Maria Louise Denst: Olper Platt - Bergisches Mundart-Wörterbuch für Kürten-Olpe und Umgebung. Schriftenreihe des Bergischen Geschichtsvereins Abt. Rhein-Berg e. V. Band 29. Bergisch Gladbach 1999. ISBN 3-932326-29-6

- Theodor Branscheid (Hrsg): "Oberbergische Sprachproben. Mundartliches aus Eckenhagen und Nachbarschaft." Band 1, Eckenhagen, 1927.

- Heinrichs, Werner: Bergisch Platt - Versuch einer Bestandsaufnahme, Selbstverlag, Burscheid, 1978

- Georg Wenker: Das rheinische Platt. 1877.

- Georg Wenker: Das rheinische Platt, (Sammlung deutsche Dialektgeographie Heft 8), Marburg, 1915.

- Georg Cornelissen, Peter Honnen, Fritz Langensiepen (editor): Das rheinische Platt. Eine Bestandsaufnahme. Handbuch der rheinischen Mundarten Teil 1: Texte. Rheinland-Verlag, Köln. 1989. ISBN 3-7927-0689-X

- Helmut Fischer: 'Wörterbuch der unteren Sieg. Rheinische Mundarten. Beiträge zur Volkssprache aus den rheinischen Landschaften Band 4. Rheinland Verlag, Köln, 1985. ISBN 3-7927-0783-7

- Ludewig Rovenhagen: Wörterbuch der Aachener Mundart, Aachen, 1912.

- Prof. Dr. Will Herrmanns, Rudolf Lantin (editor): Aachener Sprachschatz. Wörterbuch der Aachener Mundart. Beiträge zur Kultur- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte Aachens und Seiner Umgebung, Band 1. Im Auftrag des Vereins „Öcher Platt“ für den Druck überarbeitet und herausgegeben von Dr. Rudolf Lantin. 2 Bände. Verlag J. A. Mayer, 1970. ISBN 3-87519-011-4

- Adolf Steins: Grammatik des Aachener Dialekts. Herausgegeben von Klaus-Peter Lange. Rheinisches Archiv Band 141. Böhlau-Verlag, Kölle, Weimar, Wien, 1998. ISBN 3-412-07698-8

- Dr. Karl Allgeier, Jutta Baumschulte, Meinolf Baumschulte, Richard Wolfgarten: Aachener Dialekt - Wortschatz, Öcher Platt - Hochdeutsch und Hochdeutsch - Öcher Platt. Öcher Platt e.V. Aachen, 2000.

Ripuarian language

View on GrokipediaClassification and History

Linguistic Classification

Ripuarian is classified as a West Central German dialect group within the broader West Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family, specifically belonging to the Central Franconian continuum.[4] This positioning places it under the Middle German languages, distinguishing it from both the northern Low German varieties and the southern Upper German dialects.[5] Within the Central Franconian group, Ripuarian maintains close linguistic relations to Moselle Franconian, with both often grouped together as Western Central German dialects under the traditional Middle Franconian umbrella due to shared phonological and morphological features, such as patterns in plural formations and consonant developments.[6] In contrast, it differs from Low Franconian languages like Dutch and its dialects, including the transitional Limburgish, which is sometimes debated as adjacent but remains classified separately as part of the Low Franconian continuum owing to differences in the application of the High German consonant shift and other innovations.[7] A key isogloss defining Ripuarian's boundaries is the Benrath line, which separates it from Low German and Low Franconian influences to the north; south of this line, Ripuarian exhibits the shifted forms characteristic of High German, such as maken becoming machen ('to make').[7] Etymologically, Ripuarian traces its roots to Old Franconian dialects spoken by the Ripuarian Franks along the Rhine, serving as a substrate that influenced the development of Old High German and Middle Franconian varieties in the region through shared lexical and phonological elements.[8]Historical Development

The Ripuarian language derives its name from the Ripuarian Franks, a subgroup of the Frankish confederation that settled along the Rhine River in the Rhineland region, particularly around Cologne, by the mid-4th century AD as foederati allied with the Roman Empire for frontier defense.[9] This settlement marked the initial integration of Frankish speakers into the area during the Migration Period (c. 300–700 AD), where their West Germanic dialects began to overlay existing Romanized Celtic and Latin substrates from the prior Gallo-Roman occupation.[5] Ripuarian evolved from Old High German (c. 750–1050 AD) through the Middle Franconian stage (c. 1050–1500 AD), forming part of the broader West Central German dialect continuum characterized by partial participation in the High German consonant shift.[5] During this progression, substrate influences from Roman-era Latin introduced ecclesiastical and administrative vocabulary, while contacts with neighboring Low German, Dutch, French, and Southern Meuse-Rhenish (Limburgish) dialects contributed lexical borrowings and phonological features, such as tonal contrasts in certain varieties.[5] Medieval dialect formation solidified in the High Middle Ages (c. 1100–1500 AD), as Ripuarian varieties emerged distinctly in the Rhineland through interactions in trade, law codes like the Lex Ripuaria (c. 630 AD), and feudal administration under the Frankish Carolingian Empire.[9] In the 19th and 20th centuries, attempts at standardization occurred amid the rising dominance of High German, spurred by national unification efforts and linguistic reforms such as Theodor Siebs' pronunciation standard (1898) and Konrad Duden's orthography (1902), which elevated a supra-regional variety over local dialects like Ripuarian.[10] Industrialization and urbanization in the Rhineland, particularly in the Ruhr Valley from the late 19th century, accelerated dialect leveling and preservation challenges, as migrant workers from diverse regions adopted hybrid regiolects blending Ripuarian elements with standard German, leading to the erosion of traditional base dialects in urban centers.[10]Geographic Distribution

Core Regions

The Ripuarian language is primarily spoken in the federal states of North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate in western Germany, where it forms a central part of the local linguistic landscape. These areas encompass the Rhineland region, extending from the Lower Rhine to the Eifel hills, with traditional use concentrated around major river valleys and historical settlements.[3] In Belgium, the core extends to the eastern part of Liège Province within the German-speaking Community, particularly in districts like Eupen and St. Vith, which border Germany directly.[11] Further north, it reaches southern Limburg Province in the Netherlands, including border municipalities such as Vaals and Kerkrade, linking the dialect continuum across national lines.[3] Key urban centers play a pivotal role in maintaining Ripuarian varieties, with Cologne serving as the foremost hub for the Kölsch dialect, a prominent representative of the group that underscores local cultural expression through theater, festivals, and media.[12][1] Similarly, Aachen functions as an important center, where the local Öcher Platt variety of Ripuarian integrates influences from neighboring dialects while preserving core Franconian features. These cities not only host vibrant urban speech communities but also radiate influence to adjacent rural areas, where Ripuarian persists in villages and farming districts amid everyday interactions.[12] Distribution patterns within these cores reveal a blend of urban vitality and rural continuity, with denser usage in metropolitan settings like Cologne contrasted by steadier traditional retention in countryside locales across North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate.[13] Near the tripoint borders of Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands, Ripuarian overlaps with bilingual zones, facilitating mutual intelligibility with adjacent Limburgish and Low Dietsch varieties in cross-border communities.[11]Boundaries and Extent

The northern boundary of the Ripuarian language is defined by the Benrath line, an isogloss that separates it from Low German dialects to the north. This line, running roughly from east of Aachen through Benrath south of Düsseldorf and extending eastward, marks the transition where the High German consonant shift applies, as evidenced by the shift from Low German "maken" to Ripuarian "machen" for "to make."[14][2] South of this line, Ripuarian forms the western extent of the High German dialect area, with transitional features appearing in border zones like northern Düsseldorf.[14] To the south and west, Ripuarian extends into the southern Netherlands and the German-speaking Community of Belgium, but with gradual fade-outs in peripheral areas. In the Netherlands, it is spoken in southeastern Limburg near the German border, including villages like Lemiers and Kerkrade east of Maastricht, where it transitions into Limburgish dialects.[2] In Belgium, the dialect persists in the northern parts of the German-speaking Community, particularly around Eupen, where the Eupen dialect represents a Ripuarian variety influenced by cross-border contact.[15] However, usage diminishes westward toward the Romance-Germanic language border and near Maastricht, where Dutch and Limburgish predominate, creating a zone of mixed features.[16][2] The southern boundary is delineated by the Rhenish fan, a bundle of isoglosses fanning out along the Rhine that separate Ripuarian from Moselle Franconian dialects to the south and southeast. Key among these is the "dorp/dorf" isogloss, where Ripuarian retains the unshifted "dorp" (village) north of the Eifel Mountains, while Moselle Franconian shifts to "dorf" further south toward Trier and Koblenz. This fan-shaped pattern reflects incomplete application of the High German consonant shift, with Ripuarian showing shifts like *p > pf/ff after vowels but not word-finally, contrasting with more advanced shifts in Moselle Franconian. These gradual transitions occur across the Eifel region, without sharp borders, allowing for dialect continuum effects.[15] In the 20th century, the extent of Ripuarian has contracted due to urbanization, industrialization, and migration, particularly in border areas. Rapid coalmining development in southeastern Limburg and the Rhineland attracted migrants from non-dialect-speaking regions, leading to dialect leveling and erosion of features like n-deletion in Ripuarian varieties.[17] This population influx tripled densities in urban centers like Heerlen and Kerkrade, diluting traditional speech patterns and promoting Standard German or Dutch in public domains.[17] Consequently, peripheral zones near Maastricht and Eupen have seen reduced vitality, with younger speakers shifting toward regional standards amid ongoing cross-border mobility.[16][17]Speakers and Status

Number of Speakers

The Ripuarian language is estimated to have approximately 900,000 to 1 million native speakers across its core regions in Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands, based on linguistic surveys and assessments conducted in the early 2020s.[1] This figure updates earlier estimates, including about 250,000 active speakers for the prominent Kölsch variety spoken in and around Cologne.[3] Demographically, Ripuarian speakers are primarily older individuals in rural areas of the Rhineland and Eifel regions, with a notable concentration of younger urban speakers in Cologne, where fluency rates hover around 25% among the local population.[18] Data from sources like Ethnologue indicate that the language remains stable as an indigenous variety used as a first language within ethnic communities, though regional surveys highlight underreporting due to its classification as a dialect of German rather than a distinct language, which affects census and vitality assessments.[3][19] Usage trends show a decline in active speaking, particularly among younger generations influenced by standard German, but passive comprehension remains widespread and stable in core areas, with many non-fluent residents understanding the dialects through cultural exposure.[20][19]Sociolinguistic Status

Ripuarian dialects hold varying degrees of official recognition across their geographic range. In Belgium, varieties such as Low Dietsch, classified as a transitional Ripuarian Franconian dialect, have been recognized as a regional language by the Walloon regional government since 1992, affording them limited institutional support in education and cultural activities despite the country's non-ratification of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[21] In the Netherlands, some Ripuarian dialects are recognized as regional or minority languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, which the Netherlands ratified in 1996; these include varieties in the continuum with Limburgish, providing protections in areas like media and schooling. The language enjoys notable cultural prestige, particularly through traditions like the Cologne Carnival (Kölner Karneval), where the Kölsch variety of Ripuarian serves as a symbolic lingua franca in songs, performances, and public discourse, reinforcing local identity amid festivities that attract millions annually.[22] This prestige extends to media and literature, with local radio stations such as WDR Köln broadcasting programs in Ripuarian dialects to promote everyday usage, and a body of literature including works by authors like Willi Herren that celebrate regional narratives in Kölsch. Ripuarian faces sociolinguistic challenges, primarily diglossia with Standard German (Hochdeutsch), where the dialect is relegated to informal domains while Standard German dominates formal contexts like education and administration, contributing to intergenerational language shift and declining proficiency among younger speakers. Revitalization initiatives counter this trend through dialect schools offering courses in places like Cologne, such as the Akademie för uns kölsche Sproch, and community events to foster transmission and pride.[22] Post-2020 European Union policies have indirectly bolstered Ripuarian's vitality in border regions via the 2021-2027 Cohesion Policy framework, which funds cross-border projects under Interreg programs to support linguistic diversity, including educational exchanges and cultural preservation in German-Belgian-Dutch frontier areas.[23]Varieties

Major Varieties

The Ripuarian language encompasses several major varieties, primarily distinguished by regional associations and historical influences within its dialect continuum. These varieties form a transitional zone between Low Franconian and Central Franconian dialects, with prominent subgroups including West Ripuarian, Central Ripuarian, Bergisch, and Eifel dialects.[19] West Ripuarian, centered around Aachen in western Germany and extending into eastern Belgium near Eupen, is exemplified by the Aachen dialect known as Öcher Platt. This variety exhibits strong Dutch and Limburgish influences due to its position in a linguistic transition zone, incorporating borrowings from French and Walloon.[19][24] Central Ripuarian, the most standardized and prestigious variety, is represented by Colognian or Kölsch, spoken in and around Cologne. Standardized as early as the 14th to 15th centuries through literary and trade influences, Kölsch features a consistent second consonant shift and significant High German admixtures, contributing to its role as a model for other Ripuarian forms.[19][19] Other notable varieties include Bergisch, spoken in the Bergisch region around Wuppertal, which shares core Ripuarian traits like vocalism patterns but shows local innovations from proximity to the Ruhr area. Eifel dialects in the northern Eifel mountains align closely with Ripuarian, resembling Öcher Platt or Kölsch in phonology and lexicon, while serving as a buffer against Moselle Franconian to the south.[25] A key phonological marker distinguishing Ripuarian varieties is their pitch-accent system, featuring a contrast between Accent 1 (falling tone) and Accent 2 (rising-falling tone), with variations in realization across regions such as sharper contours in urban Colognian compared to more level tones in rural Eifel forms.[26] Sociolectal differences within Ripuarian highlight urban prestige forms, like the leveled and standardized Kölsch in Cologne, against more conservative rural variants in areas like the Eifel, where traditional features persist due to less exposure to standardization pressures.[17][27] In Belgium, Ripuarian variants in the Eupen area and northern parts of the Eupen-Malmedy region, often based on Colognian models, incorporate French influences and were officially recognized as a regional language in 1992; studies emphasize their vulnerability and positive community attitudes toward preservation amid bilingual contexts.[19] These major varieties exhibit gradual transitions characteristic of the broader Ripuarian continuum.[24]Dialect Continuum Features

The Ripuarian language constitutes a dialect continuum within the West Central German group, where linguistic features vary gradually across geographic space, with only minor differences observable between adjacent villages or communities. This seamless chain is particularly evident in the Rhenish fan, a bundle of isoglosses stemming from the High German consonant shift that radiate outward from the Rhine River area, marking subtle transitions in phonological developments such as the fricativization of stops. These isoglosses, including lines like the Benrath and Uerdingen, create a fan-like pattern that underscores the fluid boundaries of Ripuarian varieties rather than sharp divisions.[28][5] Mutual intelligibility remains high among neighboring Ripuarian varieties in core regions, allowing speakers from nearby locales to communicate effectively, though comprehension diminishes progressively toward the periphery, especially in transitional zones with Low Franconian dialects to the northwest. This gradient aligns with the defining properties of dialect continua, where adjacency ensures substantial overlap in vocabulary, grammar, and phonology.[29][30] Historical trade along the Rhine River fostered linguistic cohesion by enabling regular contact and exchange among communities, thereby diffusing shared features across the continuum. In contemporary contexts, increased mobility and exposure through regional media continue to reinforce connections between distant varieties, mitigating potential barriers to understanding. A key shared innovation across the Ripuarian continuum involves patterns of consonant weakening associated with the incomplete High German consonant shift, such as the variable lenition of intervocalic stops (e.g., /p/ to or /t/ to in certain positions), which exhibit consistent yet locally nuanced realizations from Aachen to the Bergisches Land. These phonological traits highlight the continuum's unity despite micro-variations.[31]Phonology

Consonant System

The consonant phoneme inventory of Ripuarian dialects, such as those spoken in the Lemiers and Cologne areas, comprises approximately 18 to 25 distinct segments (18 in Lemiers, 25 in Kölsch), including stops, affricates, fricatives, nasals, laterals, rhotics, and approximants.[2] This system reflects partial effects of the High German consonant shift, particularly in the affrication of voiceless alveolar stops to /ts/ (e.g., etymological *tīʦ > [tiːts] "tits" or "ticks").[2] Unlike Standard German, voiceless plosives /p, t, k/ are typically unaspirated in initial position (e.g., [kœlʃ] for "Kölsch"), contrasting with the aspirated [pʰ, tʰ, kʰ] of Standard German.[32] The following table presents the consonant phonemes in a standard IPA chart format, based on the Lemiers variety; minor variations occur across the dialect continuum, such as inclusion of /tʃ dʒ ʔ/ in Kölsch and occasional /tʃ/ in eastern Ripuarian forms.[2]| Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental/Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p b | t d | k g | |||||

| Affricate | ts | |||||||

| Fricative | f | v | s z | ʃ ʒ | ç | ʁ χ | ɦ | |

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||

| Lateral | l | |||||||

| Rhotic | ʁ | |||||||

| Approximant | j |

Vowel System

The Ripuarian vowel system typically features 8 to 10 monophthongs, distinguished primarily by quality and quantity, with a notable presence of front rounded vowels such as /y/, /ø/, and /œ/, alongside a central reduced vowel /ə/. Short monophthongs include /ɪ/, /ʏ/, /ʊ/, /ɛ/, /œ/, /ɔ/, /a/, and /ə/, while long counterparts encompass /iː/, /yː/, /uː/, /eː/, /øː/, /oː/, /ɛː/, /ɔː/, /aː/, and /ɑː/, though the exact inventory varies by sub-dialect, with some merging open back vowels /a/ and /ɑ/. This length distinction is phonemic, affecting meaning, as in Kölsch examples where short /ʊ/ in "Hus" (house) contrasts with long /uː/ in derived forms.[34][2]| Position | Close | Close-mid | Open-mid | Open |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front unrounded | /iː/ /ɪ/ | /eː/ | /ɛː/ /ɛ/ | /aː/ /a/ |

| Front rounded | /yː/ /ʏ/ | /øː/ | /œː/ /œ/ | |

| Central | /ə/ | |||

| Back rounded | /uː/ /ʊ/ | /oː/ | /ɔː/ /ɔ/ | |

| Back unrounded | /ɑː/ /ɑ/ |

Prosody and Intonation

The Ripuarian languages exhibit a distinctive pitch accent system, characterized by a binary contrast between two tonal accents that can distinguish lexical meanings, particularly on bimoraic syllables such as those with long vowels or vowels followed by sonorant consonants. This system aligns with the broader Franconian tonal tradition, where the accents overlay stress patterns and interact with sentence-level intonation.[2][37] The acute accent (often termed stoottoon or push tone) features a short rising-falling pitch contour, typically realized acoustically as a brief high tone followed by a sharp drop, and is associated with originally long non-high vowels. In contrast, the circumflex accent (sleeptoon or dragging tone) displays a longer rise to a sustained high pitch with a gradual or less abrupt fall, commonly on high vowels, diphthongs, or lengthened syllables from historical processes like open syllable lengthening. These accents are phonemic in many Ripuarian varieties, including those around Cologne (Kölsch) and in southeastern dialects like Lemiers, though their realization varies by dialectal subgroup.[2][37] Intonation in Ripuarian follows patterns similar to Standard German but is modulated by the lexical tones. Declarative statements typically end with a falling boundary tone, while polar questions employ a rising or high-low contour for interrogative force, and wh-questions show variable pitch alignment depending on focus placement. Lexical stress falls primarily on root syllables, with tonal accents reinforcing prominence on accented feet; vowel lengths briefly influence prosody by determining the moraic structure eligible for accent assignment. Acoustic analyses indicate that accent 1 (acute) durations are shorter (e.g., approximately 0.44 seconds in focused positions) compared to accent 2 (circumflex, around 0.48 seconds), with differences in pitch peak timing and intensity contours.[2] Ripuarian tonality shares origins with Limburgish, both stemming from a historical Franconian tone contrast that arose around the 13th century through open syllable lengthening and subsequent analogical changes. However, Ripuarian follows "Rule A" distributions, where tones neutralize in certain voiced environments (e.g., after voiced consonants), unlike the more contrast-preserving "Rule A2" in core Limburgish areas; this leads to partial convergence in border varieties but distinct realizations overall.[37] Minimal pairs illustrate the contrastive role of these accents. In the Lemiers dialect, rɔː¹s (acute: "pink") contrasts with rɔː²s (circumflex: "rust"), and wɛː¹ç ("roads") with wɛː²ç ("road"), where the superscript denotes the accent type and the pitch movement alters meaning. Similar oppositions occur in Kölsch, such as acute-accented forms like strɔ́ɔt ("street") versus circumflex in related lengthened items.[2][37] In peripheral and urban varieties, the tonal system shows signs of simplification or loss, with neutralization in post-focal positions and potential erosion due to contact with non-tonal Standard German; historical shifts like schwa deletion have already reduced contrast predictability in some areas, though core urban speech like Kölsch retains the accents robustly.[2][37]Grammar

Nominal Morphology

Ripuarian languages exhibit a nominal morphology characterized by three grammatical genders—masculine, feminine, and neuter—and four cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, and dative, with frequent syncretism particularly between nominative and accusative forms across genders.[38] Nouns themselves show limited inflectional endings, relying heavily on articles and pronouns for case and gender marking, which aligns with the broader West Central German dialect continuum. For instance, in the Mützenich variety, the masculine noun Mann ('man') appears as dä Mann in nominative and accusative, däm Mann in dative, and the genitive is rarely used, often replaced by a preposition like va (di Vrau va mingem Broor, 'the woman of my brother'). Syncretism is evident in neuter nouns like Könk ('boy'), which takes dat Könk for nominative and accusative, and däm Könk for dative.[38] Plural formation in Ripuarian involves a combination of vowel alternations (umlaut) and suffixation, mirroring patterns in Standard German but with dialectal variations in application and endings such as -e, -er, or -en. Umlaut often affects back vowels in the stem, as in Huus ('house', singular) becoming Hüüser (plural), where the -er suffix combines with fronting of /u:/ to /y:/.[38] Other examples include zero-marked plurals for some masculines (di Männ, 'the men') or simple -e for feminines (Vraue, 'women'), with the definite article unifying as di for all genders in nominative and accusative plural, shifting to dänne in dative. This system preserves Indo-European plural marking but shows analogical leveling across classes.[38] Definite articles in Ripuarian reflect case, gender, and number distinctions more robustly than nouns, with forms like de or dä for masculine nominative/accusative, dat for neuter nominative/accusative, di for feminine nominative/accusative, and dative forms däm (masculine/neuter) and dr (feminine).[38] In the Cologne (Kölsch) variety, these are pronounced with a softer onset, such as dä for masculine and dat for neuter, maintaining the core paradigm. Diminutives are productively formed with suffixes like -chen, -che, or -je, always neuter in gender and often triggering umlaut or simplification, as in Hätzche ('little heart') from Hätz or Mädche ('little girl').[39] Compared to Standard German, Ripuarian varieties display more analytic tendencies, such as reduced genitive usage and reliance on prepositional phrases, though core synthetic features like gender agreement with pronouns persist.Verbal Morphology

The verbal morphology of Ripuarian, a West Central German dialect group, follows patterns inherited from Middle High German, with simplifications and innovations typical of Rhenish varieties. Verbs are classified into three main conjugation classes: weak verbs, which form the preterite and past participle with a dental suffix (-te or -de); strong verbs, which use ablaut (vowel gradation) for these forms; and mixed verbs, which combine elements of both, often applying ablaut in the preterite but a dental suffix in the participle (e.g., denken: present dächke, preterite däch, participle jedäch). These classes align closely with those in Standard German but exhibit dialectal reductions in endings and prefixation.[40] In the present tense, indicative endings are simplified compared to Standard German, often merging forms across persons and reducing unstressed vowels. Typical singular endings include zero or -e for the first person (e.g., ich luure 'I look'), -s for the second person (do luurs 'you look'), and -t for the third person (hä luurt 'he looks'), while plural forms frequently revert to the infinitive stem with zero marking for first and third persons (mir luure 'we look', se luure 'they look') and -t for the second (ihr luurt 'you all look'). Strong verbs may show stem vowel changes or contractions, as in jonn 'go': ich jonn, do jehs, hä jeht. This paradigm reflects a tendency toward analytic structures, with person-number distinctions less rigidly marked than in High German.[40][41] The preterite tense is synthetic but less frequently used in everyday speech, reserved mainly for auxiliaries like sin 'be' (e.g., ich was) and han 'have' (e.g., ich hadde); for other verbs, weak forms add -te (e.g., luure: ich luuerte), while strong verbs employ ablaut (e.g., singe: ich sang). The perfect tense, however, dominates for past reference and is periphrastic, combining han or sin with a past participle often prefixed by je- (e.g., ich han jeluurt 'I have looked', mir sin jejange 'we have gone'). Motion and change-of-state verbs typically select sin as auxiliary. The future is expressed periphrastically with wulle 'want/will' plus infinitive (e.g., ich wull luure 'I will look'), analogous to Standard German's werden construction but with dialectal forms like wull or well.[40][42] Moods are primarily indicative, with the subjunctive formed through umlaut or ablaut on the stem vowel, often in conditional or hypothetical contexts (e.g., indicative ich luure vs. subjunctive ich lüre 'I might look'); synthetic subjunctives are rarer in speech, yielding to periphrastic alternatives like wöhr 'would' plus infinitive. Imperatives are simple, deriving from the stem with minimal marking: singular often bare stem (luur! 'look!'), plural adding -t (luurt! 'look! [pl.]'), and first-person plural using mir + infinitive (mir luure! 'let's look!'). A distinctive feature is the Rheinische Verlaufsform, a periphrastic progressive construction using sin + am + infinitive (e.g., ich ben am luure 'I am looking'), which conveys ongoing action and occurs across tenses (e.g., preterite: ich was am luure 'I was looking'; perfect: ich han am luure jewese 'I have been looking'). This form, grammaticalized from locative origins, applies to activity, accomplishment, and achievement verbs but not stative ones (e.g., *am wüsse 'knowing' is ungrammatical), and shows higher frequency with transitives.[40][42] Dialectal variations in verbal morphology are pronounced along the Ripuarian continuum, with periphrastic constructions like the Verlaufsform more prevalent in border areas toward Moselle Franconian (e.g., increased object incorporation as in am Huus söke 'house-searching' vs. separate noun phrases in central varieties). Endings may further simplify eastward (e.g., loss of -s in second person) or incorporate regional auxiliaries, such as variants of wulle in future forms. Strong verb ablaut patterns also vary, with some areas retaining Middle High German vowels more faithfully (e.g., Cologne vs. Aachen). These features underscore Ripuarian's analytic drift, favoring periphrasis over synthetic inflection in informal and progressive contexts.[42][40]Pronominal and Numeral Systems

The pronominal system in Ripuarian dialects exhibits forms typical of West Central German varieties, with distinctions for person, number, gender, and case, though the genitive case is largely obsolete and accusative and dative often merge in object pronouns. Personal pronouns include stressed and unstressed variants, with clitic forms prevalent in spoken registers for fluidity in casual speech. The first-person singular nominative is ich or iχ (with a palatal fricative [ç] or affricate in some subvarieties like Colognian), and the accusative/dative form is mich. The second-person singular nominative is du, with dich for accusative/dative. Third-person singular forms show gender agreement: masculine he or hä, feminine see or se, and neuter et, while the plural third person uses se for all genders. First-person plural is mir or mer, and second-person plural is er or ehr. Clitic forms in spoken varieties include reductions like 'n for en (accusative/dative masculine/neuter) or 'se for feminine, often encliticizing to verbs, as in ik seh'n ("I see him"). Gender agreement in third-person pronouns is sociopragmatically conditioned; for instance, female first names are predominantly referenced with neuter pronouns like et (91.5% usage in Ripuarian), signaling familiarity, while feminine se (8.5%) conveys respect or distance, particularly for older relatives.[43] Possessive pronouns in Ripuarian follow patterns akin to Standard German but with dialectal inflections for case, gender, and number to agree with the head noun. Basic forms are mein (first-person singular, "my"), dain (second-person singular, "your"), saijn (masculine third-person singular, "his"), saar (feminine, "her"), and saas (neuter, "its"), extending to plural ons ("our") and johner ("your" plural). These inflect, e.g., meins in nominative singular neuter or denger in genitive plural, though genitive usage is rare outside fixed expressions. Object cases merge in possessives tied to pronouns, as seen in mech variants paralleling mich.| Person | Nominative Singular | Accusative/Dative Singular | Possessive Base |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | ich/iχ | mich | mein |

| 2nd | du | dich | dain |

| 3rd m. | he/hä | hen | saijn |

| 3rd f. | see/se | se | saar |

| 3rd n. | et | et | saas |

| Cardinal | Form | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | een | Invariant |

| 2 | twee | |

| 3 | drëä | Umlaut from drei |

| 4 | veer | Softened |

| 5 | fäuf | Umlaut |

| 6 | sest | From sechs |

| 7 | sebbe | From sieben |

| 8 | acht | Unchanged |

| 9 | nën | From neun |

| 10 | tian | From zehn |

Orthography

Writing Conventions

The Ripuarian language lacks a unified orthography, with writers employing ad hoc systems that modify Standard German spelling to approximate dialectal phonetics. These informal conventions often retain familiar German letters and digraphs while adjusting for regional sounds, such as using <ä> to denote the lax open-mid front vowel /ɛ/ and <ß> for the alveolar fricative /s/ in intervocalic positions. Such adaptations allow for practical transcription but result in variability, as no single standard governs all Ripuarian varieties.[1] Dialect-specific practices further diversify writing approaches. In the Kölsch dialect, spoken around Cologne, the close-mid front rounded vowel /ø/ is commonly represented by <ö>, and the Akademie för uns kölsche Sproch promotes consistent rules in its Kölsch Wörterbuch, which includes phonetic guides using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) alongside modified German orthography. The Aachener dialect, influenced by proximity to Dutch, incorporates digraphs likeStandardization and Usage

Standardization efforts for the Ripuarian language, particularly its prominent Kölsch variety spoken in Cologne, have been led by the Akademie för uns Kölsche Sproch since its founding in 1983. The academy has developed an authoritative orthography aimed at making the dialect a learnable regional language, including spelling and pronunciation rules outlined in publications such as the Kölsche Wörterbuch and Kurzgrammatik.[46] In the late 1990s, the academy released Alles Kölsch, a comprehensive documentation based on authentic tape recordings that provided the first modern insight into spoken Kölsch and supported orthographic consistency.[46] In border regions of Belgium and the Netherlands, where Ripuarian dialects extend into areas like the Eifel and southeastern Limburg, local standardization has occurred through regional associations and publications tailored to specific variants, though these remain less centralized than German efforts.[47] These initiatives address the dialect continuum across national boundaries but have not achieved widespread unification. Ripuarian finds practical usage in cultural and informal contexts, including literature such as carnival songs and poetry, where groups like Bläck Fööss perform in Kölsch to celebrate Cologne's traditions. It appears on signage in Cologne, particularly in pubs and marketing materials promoting local identity, and thrives in online forums dedicated to regional dialects. Formal education remains limited, with Ripuarian not integrated into standard school curricula, though the academy offers supplementary seminars and exams leading to a Kölsch-Diplom for about 90-100 participants annually.[46] Challenges to standardization stem from the inherent diversity of Ripuarian dialects, leading to resistance against a single orthography and reliance on ad hoc writing conventions. Recent developments post-2015, including the academy's online dictionary and apps for learning, have aided unification efforts. In the 2020s, digital revitalization has advanced through projects like the academy's Klaaf e-paper and the Ripuarian Wikimedia edition, approved in 2006 as a collaborative platform for content creation in the language.[46][48]References

- https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Requests_for_new_languages/Wikipedia_Ripuarian