Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Alexander Rodchenko

View on WikipediaThis article is missing information about his involvement in the creation of propaganda. (July 2025) |

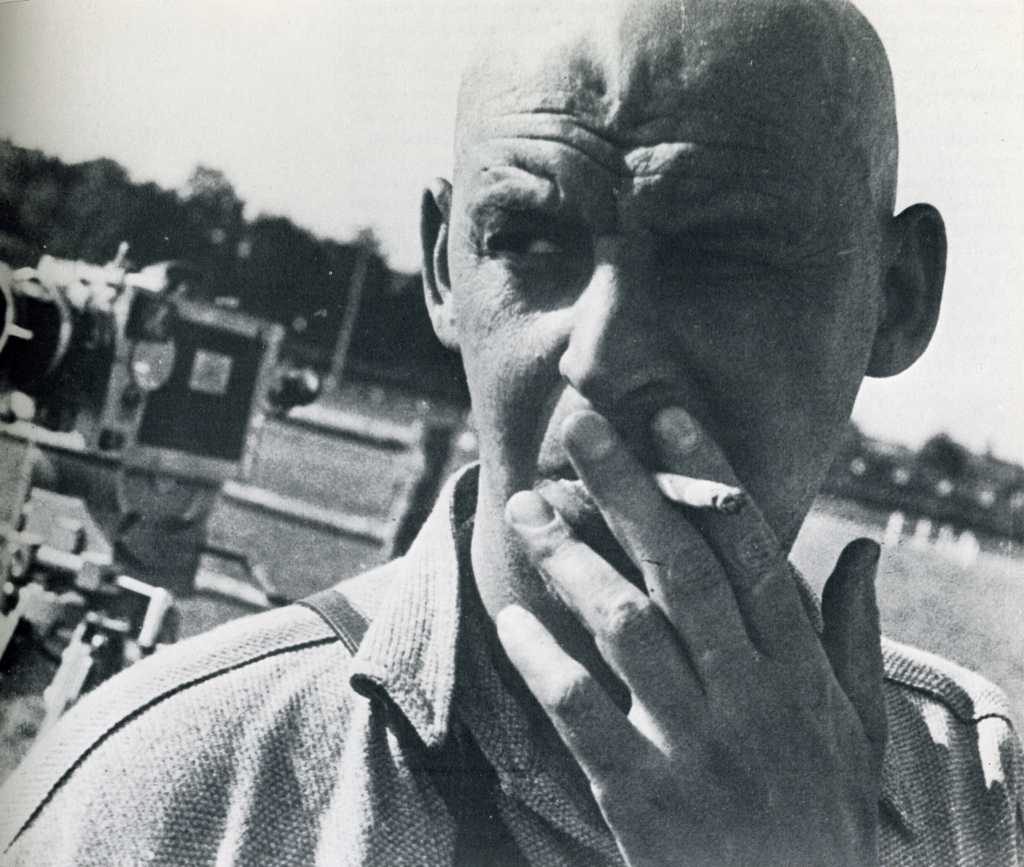

Aleksander Mikhailovich Rodchenko (Russian: Александр Михайлович Родченко; 5 December [O.S. 23 November] 1891 – 3 December 1956) was a Russian and Soviet artist, sculptor, photographer, and graphic designer. He was one of the founders of constructivism and Russian design; he was married to the artist Varvara Stepanova.

Key Information

Rodchenko was one of the most versatile constructivist and productivist artists to emerge after the Russian Revolution. He worked as a painter and graphic designer before turning to photomontage and photography. His photography was socially engaged, formally innovative, and opposed to a painterly aesthetic. Concerned with the need for analytical-documentary photo series, he often shot his subjects from odd angles—usually high above or down below—to shock the viewer and to postpone recognition. He wrote: "One has to take several different shots of a subject, from different points of view and in different situations, as if one examined it in the round rather than looked through the same key-hole again and again."

He is also known for developing the early corporate identity of the airline Dobrolyot, later Aeroflot, and designed its world-famous "Winged Hammer and Sickle" logo.[1][2]

Life and career

[edit]

Rodchenko was born in St. Petersburg to a working-class family who moved to Kazan after the death of his father, in 1909.[3] He became an artist without having had any exposure to the art world, drawing much inspiration from art magazines. In 1910, Rodchenko began studies under Nicolai Fechin and Georgii Medvedev at the Kazan Art School, where he met Varvara Stepanova, whom he later married.

After 1914, he continued his artistic training at the Stroganov Institute in Moscow, where he created his first abstract drawings, influenced by the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich, in 1915. The following year, he participated in "The Store" exhibition organized by Vladimir Tatlin, who was another formative influence.

Rodchenko's work was heavily influenced by Cubism and Futurism, as well as by Malevich's Suprematist compositions, which featured geometric forms deployed against a white background. While Rodchenko was a student of Tatlin's he was also his assistant, and the interest in figuration that characterized Rodchenko's early work disappeared as he experimented with the elements of design. He used a compass and ruler in creating his paintings, with the goal of eliminating expressive brushwork.[4]

Rodchenko worked in Narkompros and he was one of the organizers of RABIS. RABIS was formed in 1919–1920.[5]

Rodchenko was appointed Director of the Museum Bureau and Purchasing Fund by the Bolshevik Government in 1920, responsible for the reorganization of art schools and museums. He became secretary of the Moscow Artists' Union and set up the Fine Arts Division of the People's Commissariat for Education, and helped found the Institute for Artistic Culture.[6]

He taught from 1920 to 1930 at the Higher Technical-Artistic Studios (VKhUTEMAS/VKhUTEIN), a Bauhaus organization with a "checkered career". It was disbanded in 1930.[6]

In 1921 he became a member of the Productivist group, with Stepanova and Aleksei Gan, which advocated the incorporation of art into everyday life. He gave up painting to concentrate on graphic design for posters, books, and films. He was deeply influenced by the ideas and practice of the filmmaker Dziga Vertov, with whom he worked intensively in 1922.

Impressed by the photomontage of the German Dadaists, Rodchenko began his own experiments in the medium, first employing found images in 1923, and from 1924 on, shooting his own photographs as well.[7] His first published photomontage illustrated Mayakovsky's poem, "About This", in 1923. In 1924, Rodchenko produced what is likely his most famous poster, an advertisement for the Lengiz Publishing House sometimes titled "Books", which features a young woman with a cupped hand shouting "книги по всем отраслям знания" (Books in all branches of knowledge), printed in modernist typography.[8][9]

From 1923 to 1928 Rodchenko collaborated closely with Mayakovsky (of whom he took several portraits) on the design and layout of LEF and Novy LEF, the publications of Constructivist artists. Many of his photographs appeared in or were used as covers for these and other journals. His images eliminated unnecessary detail, emphasized dynamic diagonal composition, and were concerned with the placement and movement of objects in space. During this period, he and Stepanova painted the well-known panels of the Mosselprom building in Moscow. Their daughter, Varvara Rodchenko [d], was born in 1925.

Criticism and censorship

[edit]Throughout the 1920s, Rodchenko's work was very abstract. Rodchenko joined the October Group of artists in 1928 but was expelled three years later, charged with "formalism", an accusation first raised in the pages of Sovetskoe Foto in 1928.[10]

As changes developed in the Soviet Union in the late 1920's (particularly the exiles of Leon Trotsky in 1928 and from the Soviet Union entirely in 1929, along with the rise of Joseph Stalin), so did the form by which Soviet art was expected to conform to. In the 1930s, with the changing Party guidelines governing artistic practice in favor of Socialist realism, the artist and photographer saw mounting criticism from state-sponsored art critics and the Party. Osip Brik, a well-established author and art critic who was similarly entrenched in the politics and evolving art-culture, offered what was scathing criticism at the time for the photographer’s series on The Building on Miasnitskaia Street and Pine Trees in Pushkino, saying, “one should not depict an isolated building or tree, which may be beautiful but which will be a painting, will be aesthetic.”[11] Similarly to Brik, Sergei Tretyakov attacked Aleksandr Rodchenko’s stylized work, saying, “Instead of exploring the whole range of utilitarian goals confronting photography, Rodchenko is only interested in its aesthetic function. He reduces its activity to simply a reeducation of taste based on certain new principles. We are seeking ‘a new aesthetics’: the capacity to see the world in a new way.”[12]

In 1935, the Masters of Soviet Art exhibition was held, but Rodchenko was only allowed to produce work for the exhibit under the command that he publicly denounce his previous formalist works. The self-denouncement was published in Sovetskoe Foto, adding insult to injury. "Henceforth I want to decisively reject putting formal solutions to a theme in the first place and ideological ones in second place; and at the same time I want to search inquisitively for new riches in the language of photography, in order, with its help, to create works that will stand on a high political and artistic level, works in which the photographic language will fully serve Socialist Realism.”[13]

Despite denouncement and censorship, Rodchenko oscillated between conformity and rebellion in his work, producing one of his most famous photos in 1934, Girl with Leica, which followed similar stylistic choices to the artist and photographer's prior work.

Retirement and death

[edit]He returned to painting in the late 1930s, stopped photographing in 1942, and produced abstract expressionist works in the 1940s. He continued to organize photography exhibitions for the government during these years. He died in Moscow in 1956.

Influence

[edit]Much of the work of 20th century graphic designers is a direct result of Rodchenko's earlier work in the field.[citation needed] His influence has been pervasive. American conceptual artist Barbara Kruger owes a debt to Rodchenko's work.[citation needed]

His portrait of Lilya Brik has inspired a number of subsequent works, including the cover art for a number of music albums. Among them are the influential Dutch punk band The Ex, which published a series of 7" vinyl albums, each with a variation on the Lilya Brik portrait theme, the cover of Mike + the Mechanics album Word of Mouth, and the cover of the Franz Ferdinand album You Could Have It So Much Better. The poster for One-Sixth Part of the World was the basis for the cover of "Take Me Out", also by Franz Ferdinand.

The end of painting

[edit]In 1921, Rodchenko executed the first true monochrome paintings, first displayed in the 5x5=25 exhibition in Moscow. For artists of the Russian Revolution, Rodchenko's radical action was full of utopian possibility. It marked the end of easel painting – perhaps even the end of art – along with the end of bourgeois norms and practices. It cleared the way for the beginning of a new Russian life, a new mode of production, a new culture. Rodchenko later proclaimed, "I reduced painting to its logical conclusion and exhibited three canvases: red, blue, and yellow. I affirmed: it's all over."[14]

Photobooks (published posthumously)

[edit]- Alexander Rodchenko. Edited by National Center of Cinematography and the moving image. New York: Pantheon, 1987. ISBN 0-394-75624-X

- Rodchenko – Photography – 1924 - 1954. Edited by Alexander Lavrentiev. Cologne: Könemann, 1995. ISBN 3-89508-110-8

- Rodchenko. Edited by Peter MacGill. Göttingen: Steidl, 2012. ISBN 978-3-869302-45-4

See also

[edit]Sources

[edit]- "Aleksander Rodchenko: Design Is History". Designishistory.com. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- Dabrowski, Magdalena, Leah Dickerman, Peter Galassi, A. N. Lavrentʹev, and V. A. Rodchenko. Aleksandr Rodchenko. New York, N. Y.: Museum of Modern Art, 1998.

- "History of Art: Alexander Rodchenko". All-art.org. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- Savvine, Ivan. "The Art Story: Modern Art Movements". Modern Art Movements. Theartstory.org. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- "THE COLLECTION". Moma.org. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- "Alexander Rodchenko: The Simple and the Commonplace," Hugh Adams. Artforum, Summer 1979. Page 28.

References

[edit]- ^ ORLOV, Boris (4 February 2013). "Добрые крылья «Добролета»" [Good wings of "Dobrolet"]. Komsomolskaya Pravda (in Russian).

- ^ Малютина, Наталья (2013). "Крылья Советов: история бренда "Аэрофлот"". Информационно-аналитический портал Sostav.ru (in Russian).

- ^ John E. Bowlt, "Aleksandr Rodchenko Experiments for the Future: Diaries, Essays, Letters, and Other Writings," Museum of Modern Art New York, 2005, Page 31.

- ^ Milner, John, "Rodchenko, Aleksandr", Oxford Art Online

- ^ Художник Илья Клейнер >> Библиотека >> Великие художники XX века >> Бoгдaнoв П.С., Бoгдaнoвa Г.Б.: "Родченко Александр Михайлович".

- ^ a b "Alexander Rodchenko: The Simple and the Commonplace," Hugh Adams. Artforum, Summer 1979. Page 28.

- ^ Mrazkova, Daniela and Remes, Vladimir "Early Soviet Photographers." Museum of Modern Art Oxford, Oxford, 1982, ISBN 0-905836-27-8

- ^ Güner, Fisun (13 June 2016). "From kitchen slaves to industrial workers – the superwomen of Soviet art". The Guardian.

- ^ Thompson, Mark (4 June 2010). "Red and black and spread all over | The Japan Times". The Japan Times.

- ^ Tupitsyn, M. (1994). Against the Camera, for the Photographic Archive. Art Journal, 53(2), 58–62.

- ^ Tupitsyn, Margarita (1996). The Soviet photograph, 1924-1937 (1st ed.). The Yale University Press. p. 41. OCLC 468734230.

- ^ Tupitsyn, Margarita (1996). The Soviet photograph, 1924-1937 (1st ed.). The Yale University Press. p. 41. OCLC 468734230.

- ^ "Rodchenko: The impact of revolution and counterrevolution". World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ Akbar, Arifa (2 January 2009). "Drawing a blank: Russian constructivist makes late Tate debut". Independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

External links

[edit]Alexander Rodchenko

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Childhood and Formative Influences

Aleksandr Mikhailovich Rodchenko was born on December 5, 1891, in Saint Petersburg, Russia (November 23 by the Julian calendar then in use), to a working-class family residing in an apartment above a local theater.[7][8] His father, Mikhail Mikhailovich Rodchenko (b. 1852), served as a props manager at the theater, handling the construction and assembly of stage scenery and objects, while his mother, Olga Evdokimovna Paltusova (b. 1865), worked as a washerwoman to support the household.[8][9] From an early age, Rodchenko was immersed in the theater's backstage environment, observing the fabrication of props, costumes, and sets, which fostered his initial fascination with three-dimensional construction and practical design over purely representational art.[7][9] This hands-on exposure to functional craftsmanship—rather than formal aesthetic training—shaped his later emphasis on utility in art, distinguishing him from contemporaries focused on abstract expression.[7] His working-class upbringing instilled a pragmatic worldview, prioritizing empirical problem-solving and material realities over theoretical idealism.[10] The death of his father in 1909, when Rodchenko was 18, plunged the family into financial hardship, prompting a relocation to Kazan, where relatives resided, to seek stability.[7][10] In this provincial setting, away from Petersburg's cultural hubs, Rodchenko turned to self-directed drawing and sketching as both a creative outlet and a means of contributing to family income, honing skills in linear perspective and geometric forms influenced by his prior theater observations.[9][10] These formative experiences—rooted in manual labor, loss, and adaptive resourcefulness—laid the groundwork for his rejection of bourgeois art traditions in favor of constructivist principles aligned with industrial utility.[7]Artistic Training in Moscow

In October 1915, Alexander Rodchenko moved to Moscow and enrolled in the graphic department of the Stroganov School of Applied Art, an institution emphasizing industrial and decorative design.[8][11] There, he undertook studies in drawing, painting, art history, and applied graphic techniques, aligning with the school's curriculum focused on practical artistic skills for manufacturing and crafts.[7] His training incorporated elements of architecture and sculpture, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of the Stroganov program.[12] Rodchenko's education at Stroganov was disrupted in spring 1916 by compulsory military service, though he returned to complete his coursework amid the uncertainties of World War I and the impending Russian Revolution.[8] By June 1917, he had finished the required studies and received a certificate of completion, but lacked the formal secondary education prerequisite for a full diploma.[8] This period exposed him to Moscow's burgeoning avant-garde scene, where he began producing early abstract geometric constructions using compass and ruler, as evidenced by his participation in the March 1916 "The Store" exhibition.[8][7] These foundational experiences at Stroganov honed Rodchenko's technical proficiency in linear construction and spatial abstraction, laying groundwork for his shift toward constructivism while underscoring the school's role in bridging traditional fine arts with utilitarian design principles.[7]Emergence in the Avant-Garde

Abstract Painting and Sculpture

Rodchenko initiated his abstract explorations in painting around 1915, producing non-representational compositions such as Dance. An Objectless Composition, which featured dynamic geometric forms devoid of figurative elements.[7] These early works reflected influences from Futurism and emerging Suprematist ideas, emphasizing pure form and movement over narrative content.[13] By 1918, Rodchenko advanced into non-objective painting with a series of monochromatic black canvases, including Non-Objective Painting no. 80 (Black on Black), executed in oil on canvas as a deliberate counterpoint to Kazimir Malevich's white Suprematist paintings of the same period.[14] This series prioritized tonal variation and surface texture within a single hue to evoke spatial depth and luminosity, challenging perceptual boundaries in abstract art.[15] Rodchenko reportedly coined the term "non-objective art" to describe these innovations in 1918.[16] In 1919, he continued this trajectory with additional non-objective oils, such as Non-Objective Painting, measuring 33 1/4 x 28 inches, which further abstracted geometric motifs into rigorous, planar compositions.[17] These paintings were displayed at the 10th State Exhibition: Non-Objective Art and Suprematism in Moscow, underscoring Rodchenko's commitment to art's autonomy from representation.[18] Rodchenko's sculptural abstractions emerged concurrently, with his first three-dimensional constructions dating to 1917, evolving from planar experiments into volumetric forms.[19] By circa 1920, he produced hanging Spatial Constructions, such as Spatial Construction no. 12, fabricated from light plywood through concentric cuts in a single geometric plane—typically circular or oval—allowing the piece to unfold into a dynamic, suspended structure painted silver to enhance light reflection and spatial interplay.[20][21] These works rejected traditional pedestal-based sculpture in favor of kinetic, environment-engaging forms that emphasized transparency, line, and the dematerialization of mass, aligning with Constructivist principles of utility and spatial dynamics.[22]Adoption of Constructivism

Rodchenko's transition to Constructivism occurred amid the post-revolutionary fervor in Russia, building on his earlier experiments with abstract forms influenced by Suprematism but rejecting its emphasis on pure, non-objective art as insufficiently tied to material production and social utility. By late 1920, he had begun constructing three-dimensional spatial objects from wood, wire, and other industrial materials, viewing them as "laboratory constructions" that prioritized engineering principles over aesthetic contemplation.[22] These works marked a deliberate shift from planar abstraction to tangible, functional structures intended to serve the Bolshevik vision of art as a tool for societal transformation.[7] In April 1921, Rodchenko co-founded the First Working Group of Constructivists alongside his wife Varvara Stepanova and Aleksei Gan, formalizing the movement's principles at the Institute of Artistic Culture (Inkhuk) in Moscow. The group adopted "Constructivism" as its explicit designation during January to April of that year, emphasizing the creation of "material structures" for communist expression rather than autonomous artworks.[23] This adoption was crystallized in the 1921 exhibition 5x5=25, where Rodchenko exhibited monochromatic paintings in pure red, yellow, and blue, declaring them the "final" evolution of painting before its obsolescence, thereby redirecting his practice toward constructive, utilitarian design.[24] The group's manifesto, Who We Are: Manifesto of the Constructivist Group (circa 1921–1922), co-authored by Rodchenko, Stepanova, and Gan, rejected bourgeois art traditions like building "Pennsylvania Stations" for spectacle, instead advocating for art integrated into everyday production and proletarian needs.[25] Rodchenko's adoption reflected a broader ideological commitment to align artistic innovation with Soviet industrialization, influencing his subsequent turn to photography, typography, and industrial design as extensions of Constructivist tenets.[26]Key Artistic Manifestos and Innovations

Declaration of the End of Painting

In September 1921, Alexander Rodchenko exhibited three monochrome oil-on-canvas paintings—Pure Red Color, Pure Yellow Color, and Pure Blue Color—at the 5×5=25 Constructivist exhibition in Moscow, an event organized to showcase abstract art by five artists including Rodchenko, Lyubov Popova, and Alexander Vesnin.[27] These works, each consisting of a single unmodulated hue covering the entire surface without line, form, or spatial illusion, represented Rodchenko's culmination of non-objective painting experiments begun in the late 1910s, where he had progressively reduced composition to linear constructions and spatial abstractions.[27] Alongside these, he displayed paintings titled Line and Cell, further emphasizing pure elements over representational or decorative content.[27] Rodchenko framed this presentation as the definitive "end of painting," arguing that traditional easel painting had exhausted its formal possibilities and could no longer serve revolutionary purposes in a post-1917 Soviet context demanding utilitarian production over bourgeois aesthetics.[28] By isolating primary colors without mixture or gradation, the monochromes rejected illusionism and composition as inherited from Western art traditions, positioning them as a logical endpoint to Suprematist and Constructivist explorations of pure form initiated by Kazimir Malevich and others. This stance aligned with Constructivism's broader ideology, which viewed art as a tool for social engineering rather than autonomous expression, prompting Rodchenko's subsequent pivot to three-dimensional constructions, photography, and design.[29] The declaration provoked mixed reactions: admirers saw it as a bold theoretical advance, liberating artists from outdated media, while critics decried it as nihilistic, fearing it undermined painting's cultural role amid Soviet cultural policy shifts.[30] Rodchenko later reinforced this position in writings and practice, destroying many earlier canvases to underscore irreversibility, though the 1921 monochromes survive as artifacts of his transition.[31] Exhibited dimensions were modest—approximately 38 × 31 cm each—prioritizing conceptual purity over scale, and they prefigured international monochrome trends while rooting in Russian avant-garde materialism.[32]Shift to Functional Design

In 1921, at the 5x5=25 exhibition in Moscow, Rodchenko exhibited three monochrome canvases—Pure Red Color, Pure Yellow Color, and Pure Blue Color—positioning them as the culmination of painting's possibilities, having reduced it to pure color without composition, line, or texture.[2] [33] This act symbolized his rejection of easel painting as obsolete in the post-revolutionary era, asserting that artists must redirect their expertise toward production and utility to support societal reconstruction rather than autonomous aesthetic pursuits.[7] Embracing Productivism—a utilitarian extension of Constructivism—Rodchenko advocated for artists to integrate into industrial processes, designing objects that mirrored the efficiency and geometry of machine production for mass use.[34] [7] From 1920 to 1930, he taught construction and metalworking at VKhUTEMAS (Higher Art and Technical Studios) in Moscow, where he served as dean of a department from February 1922, instructing students in applying abstract principles to practical fabrication such as furniture and household implements.[2] [35] Rodchenko's functional designs included geometric textile patterns and workwear prototypes developed with his wife, Varvara Stepanova, emphasizing durable, modular forms suited to proletarian needs; he also created interiors for workers' clubs, featuring communal tables, book stands, and integrated lighting to promote collective efficiency.[7] [36] [6] These efforts reflected a causal commitment to art as a tool for engineering everyday environments, prioritizing material functionality over decorative excess in alignment with Soviet industrialization goals.[37]Photography and Graphic Design Contributions

Pioneering Photographic Techniques

Rodchenko turned to photography in 1924, seeking to integrate original images into his constructivist projects after relying on found photographs for earlier designs.[38] This shift aligned with his experimental ethos, encapsulated in the slogan "Our duty is to experiment," as he applied constructivist principles to capture and manipulate reality mechanically.[39] In 1925, during a trip to Paris, he purchased a handheld camera, which facilitated spontaneous compositions unbound by studio constraints.[2] His core innovations involved radical viewpoints and foreshortening, employing non-vertical angles—such as overhead, low, and diagonal perspectives—to disrupt conventional framing and emphasize spatial dynamics, geometry, and motion.[2] These techniques challenged static representation, urging viewers to perceive everyday objects and scenes as constructed forms infused with ideological energy. Rodchenko advocated serial shooting from multiple angles to build comprehensive visual narratives, prioritizing composition, light contrasts, and distortion over naturalistic fidelity.[38] Exemplifying this, his 1928 At the Telephone deploys an overhead view to elongate the subject's form against a wall, underscoring technological modernity through abstracted lines.[40] Rodchenko further advanced photomontage by initiating experiments in 1923 with cut-and-pasted found images, evolving by 1924 to incorporate his own photographs as modular elements in composite designs.[13] He treated photographs as raw, collectivized material—suppressing singular details via cropping, overlapping, and retouching—to forge functional visuals for propaganda and periodicals like LEF.[41] In works like the 1925 series on Miasnitskaia Street, he combined worm's-eye and bird's-eye shots to monumentalize architecture, blending documentary precision with avant-garde abstraction.[6] These methods, disseminated through journals and exhibitions, positioned photography as a tool for perceptual revolution, influencing Soviet visual culture by prioritizing utility and ideological clarity over artistic subjectivity. His 1930 Pioneer, shot from directly below, dramatically elevates a young girl, symbolizing upward-striving collectivism via extreme foreshortening.[42]Typography, Posters, and Book Design

Rodchenko began experimenting with typography and graphic design in the early 1920s as part of his constructivist shift toward functional art, rejecting decorative elements in favor of dynamic, utilitarian layouts that prioritized readability and ideological impact.[19] In 1922, he designed his first book cover and explored asymmetric compositions, integrating bold sans-serif fonts and spatial constructions to convey motion and modernity.[19] These innovations drew from constructivist principles, treating type as a structural element akin to engineering, often tilted at angles to disrupt static reading and evoke revolutionary energy.[43] His poster work, starting in 1923, exemplified this approach through stark contrasts, photomontage, and imperative messaging tailored for mass propaganda.[44] A notable example is the 1923 poster for Dobrolet, the Soviet state airline, featuring an airplane in dynamic flight rendered in black, white, and red to symbolize technological progress and accessibility.[44] Rodchenko's most iconic poster, "Books!" (1924), produced for the Lengiz Publishing House, depicts a woman's pointing hand in photomontage emerging from layered book stacks, with diagonal red sans-serif text demanding "Books!" to promote literacy across all knowledge branches.[45] This design's aggressive perspective and cropped elements broke from symmetrical traditions, influencing Soviet graphic standards by emphasizing direct visual agitation over aesthetic refinement.[46] In book design, Rodchenko's contributions spanned handmade experimental volumes in the late 1910s—using carbon-copied pages with Futurist-inspired asymmetry—to mass-produced editions in the 1920s that served Bolshevik cultural goals.[47] Collaborating with poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, he incorporated photographic portraits into layouts around 1924, such as in series blending text and image for agitprop effect.[6] By 1929, works like Rechevik. Stikhi (Orator. Verse) featured innovative covers and interiors with slanted typography and geometric framing, aligning verse with constructivist form to enhance public dissemination of proletarian literature.[47] These designs, often executed with his wife Varvara Stepanova, prioritized economical production techniques like linocut and offset printing, reflecting a commitment to art's integration into everyday Soviet life.[2]Political Engagement and Soviet Alignment

Support for the Bolshevik Revolution

Rodchenko enthusiastically endorsed the Bolshevik-led October Revolution of October 25, 1917 (Julian calendar), perceiving it as a radical break from tsarist autocracy that aligned with his constructivist vision of art as a tool for societal transformation rather than bourgeois decoration.[5] He viewed the upheaval as an impetus to integrate aesthetics with proletarian needs, rejecting traditional fine arts in favor of functional designs that could advance communist construction.[7] This stance reflected his belief, shared among Moscow-based avant-gardists, that the revolution demanded artists to serve the dictatorship of the proletariat by applying abstract principles to everyday utility.[6] In the immediate aftermath, Rodchenko relocated artistic efforts toward state-aligned initiatives, participating in post-revolutionary exhibitions and educational programs aimed at inculcating Bolshevik ideology among workers and peasants.[48] By 1918, he had begun teaching at Moscow's free art studios (SVOMAS), where he propagated constructivist methods as compatible with Lenin's cultural policies, emphasizing production art (produktsionnoe iskusstvo) to foster industrial efficiency under socialism.[5] His writings from this period, including contributions to constructivist journals, articulated art's subordination to revolutionary goals, critiquing pre-1917 easel painting as elitist and incompatible with the new order.[7] Rodchenko's alignment was not merely opportunistic but rooted in a conviction that Bolshevik materialism enabled the realization of geometric abstraction in public life, as evidenced by his co-founding of the Obmokhu society in 1920, which trained artists for Soviet tasks.[6] Despite later ideological pressures, his early support positioned constructivism as a vanguard for Bolshevik cultural engineering, influencing policies like the 1920 Plan of Monumental Propaganda, though Rodchenko focused more on utilitarian objects than commemorative monuments.[5] This phase marked his shift from pure abstraction to ideologically directed creativity, prioritizing empirical utility over aesthetic autonomy.[7]Production of Propaganda Materials

Following the Bolshevik Revolution, Rodchenko produced posters promoting Communist Party narratives, including the 1919 work 1919 in Soviet Russia, poster no. 20 from the series The History of the All-Union Communist Party, which depicted revolutionary events through bold graphic forms.[49] In the early 1920s, he contributed to state propaganda efforts by designing materials for public dissemination, aligning his constructivist techniques with ideological messaging to mobilize support for Soviet initiatives.[37] By 1923, Rodchenko created advertisements for Mosselprom, the state agency tasked with promoting Soviet consumer goods such as table oil and bread, using dynamic photomontage and typography to foster enthusiasm for centralized production and distribution.[6] That year, he also designed a poster for Dobrolet, the Soviet state airline, emphasizing technological progress and national unity through aviation.[50] These works extended propaganda beyond overt politics to everyday economic mobilization, reflecting Rodchenko's view of design as a tool for constructing socialist consciousness.[7] In the 1930s, amid pressures from Stalinist cultural policies, Rodchenko adapted his methods to official propaganda outlets, notably designing the layout and photographs for issue no. 12 of USSR in Construction in 1933, dedicated to the Baltic-White Sea Canal project, which portrayed forced-labor infrastructure as a triumph of proletarian engineering.[51] This multilingual magazine, produced for international audiences, integrated his angled photography and montage to glorify Five-Year Plan achievements, though it omitted the project's human costs estimated at tens of thousands of deaths.[30] His involvement underscored a pragmatic shift toward state-sanctioned forms, prioritizing utility in service of regime narratives over avant-garde experimentation.[52]Controversies and Ideological Conflicts

Criticisms of Constructivism's Utilitarianism

Criticisms of Constructivism's utilitarianism, especially in its Productivist variant advanced by Alexander Rodchenko, emerged from fellow avant-garde artists who viewed it as a degradation of art's autonomy into mere craftsmanship. "Pure" Constructivists like Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner, in their 1920 Realistic Manifesto, repudiated the excessive focus on practical utility, arguing it perverted the movement's original emphasis on abstract, metaphysical construction by subordinating form to industrial production and proletarian needs.[37] This critique held that Rodchenko's shift toward designing everyday objects—such as clothing patterns and furniture prototypes in the early 1920s—abandoned the non-objective purity of geometric abstraction for a reductive functionalism that lacked deeper philosophical or aesthetic transcendence.[37] Within Soviet architectural and artistic circles, Constructivism's functionalism was lambasted for promoting vulgar materialism and aesthetic nihilism, reducing creative expression to engineering tasks devoid of beauty or ideological substance. Critics associated with VOPRA (All-Union Society of Proletarian Architects), such as A. I. Mikhailov in 1932, condemned the approach as built on "vulgar materialism" and "formal-technical functionalism," which prioritized machine-like efficiency over dialectical content and human psychological needs, reflecting bourgeois mechanicism rather than socialist realism.[53] Nikolai Dokuchaev of ASNOVA similarly equated Constructivists' "functional method" with sterile Western models, like German Functionalism, arguing it oversimplified design by ignoring psychotechnic influences on perception and societal participation, thus failing to foster genuine ideological engagement.[54] By the late 1920s, such views contributed to official rejections, as seen in the 1930 Central Committee decree critiquing utopian asceticism in Constructivist housing proposals, which enforced coercive minimalism under the guise of utility, ultimately paving the way for Socialist Realism's representational mandates.[53] These objections highlighted a core tension: utilitarianism's insistence on art serving production—epitomized by Rodchenko's 1921 manifesto with Varvara Stepanova calling for artists to enter factories—risked eroding aesthetic value and individual creativity in favor of state-aligned conformity, leading to designs criticized for sterility and oversimplification of human experience.[37][53] While proponents like Osip Brik praised Rodchenko's "iron constructive power" in shaping objects directly, detractors contended this trajectory exemplified a broader philosophical flaw in prioritizing instrumental ends over art's intrinsic capacity to inspire or critique society independently.[37]Alignment with State Propaganda and Ethical Debates

Rodchenko's constructivist ideology, emphasizing art's functional role in serving the proletariat and state, led him to produce extensive propaganda materials aligned with Soviet directives, particularly from the late 1920s onward. He created photomontages, posters, and designs promoting Bolshevik achievements, such as industrialization under the Five-Year Plans, and contributed to magazines like USSR in Construction, the flagship publication for Stalinist propaganda issued in multiple languages from 1930 to 1941.[55][51] A notable example of this alignment occurred in 1933, when Rodchenko photographed and designed Issue No. 12 of USSR in Construction, dedicated to the White Sea–Baltic Canal project. The 227-kilometer canal, completed in under two years, relied on forced labor from approximately 126,000 Gulag prisoners, with official Soviet records reporting about 12,000 deaths from malnutrition, accidents, and executions, though independent estimates suggest up to 25,000 fatalities.[51][56] In these works, Rodchenko employed dynamic angles, serial photography, and avant-garde layouts to depict prisoners as heroic figures undergoing ideological "reforging" through productive labor, thereby endorsing the state's narrative of transformative socialism while omitting the project's coercive brutality and human toll. This approach reflected his earlier 1921 declaration that pure art was obsolete, prioritizing instead "construction" for societal utility, which constructivists like Rodchenko viewed as essential to the revolutionary project.[51][57] Ethical debates surrounding Rodchenko's propaganda efforts center on the tension between his genuine ideological commitment to communism and the moral compromise of legitimizing a regime's repressive apparatus. Critics argue that by glorifying Gulag labor and Stalinist policies— which facilitated mass terror and economic coercion—Rodchenko subordinated constructivism's innovative potential to state deception, paving the way for the suppression of avant-garde art in favor of socialist realism by the mid-1930s.[58][59] Defenders, however, contend that his work embodied the era's productivist ethos, where artists sought to influence mass consciousness toward utopian goals, and that refusing state commissions risked marginalization or worse amid intensifying purges. Rodchenko's later self-criticism in Soviet publications, prompted by official rebukes of his "formalism," underscores the coercive dynamics, yet his persistence in applied design suggests a pragmatic adaptation rather than outright dissent.[60][61]Later Career, Censorship, and Death

Adaptation to Socialist Realism Pressures

In the early 1930s, Soviet cultural authorities increasingly targeted avant-garde artists like Rodchenko for "formalism," a term denoting perceived bourgeois abstraction disconnected from proletarian realities, as Stalin consolidated control over the arts following the 1932 decree uniting creative unions under Party oversight.[7] This pressure intensified after the 1930 dissolution of VKhUTEMAS, Rodchenko's teaching institution, depriving him of stable income and compelling a pivot to state-sanctioned applied arts.[62] By 1931, his experimental photographs—characterized by extreme angles and distortions—faced sharp rebukes at exhibitions like "10 Years of October," where critics accused them of contorting everyday life into unnatural forms incompatible with socialist content demands.[61] Rodchenko responded by moderating his stylistic innovations, adopting more direct, eye-level compositions in photojournalism to emphasize heroic labor and industrial progress, thereby aligning with the nascent Socialist Realism doctrine formalized in 1934, which prioritized accessible, optimistic depictions of Soviet achievement.[7] A pivotal instance occurred in 1933, when he documented the White Sea-Baltic Canal—a canal system hastily built from 1931 to 1933 using forced labor from approximately 126,000 Gulag prisoners, resulting in an estimated 12,000 to 25,000 deaths from harsh conditions. For issue 12 of the propaganda magazine USSR in Construction, Rodchenko supplied photographs and designed layouts portraying the project as a triumphant feat of reeducation and redemption for "former enemies of the people," uncritically endorsing the official narrative despite its factual distortions.[62] [63] This work exemplified his pragmatic concessions, as he later reflected on the era's constraints in private notes, though public defenses maintained fidelity to Party lines.[62] Throughout the mid-1930s, as Socialist Realism solidified, Rodchenko's Constructivist abstractions were publicly denounced, prompting further adaptation into commissioned photo series on sports events, aviation feats, and mass parades, executed in a realist mode to evade outright censorship.[37] While sustaining his career through magazines and book designs, these shifts curtailed his experimental freedom, with authorities viewing persistent formalism as ideological sabotage; by 1937, during the Great Purge, indirect threats via associates' arrests underscored the risks of non-conformity.[7] Rodchenko's late-1930s return to easel painting remained representational and subdued, avoiding exhibition to sidestep conflict with state mandates.[7]