Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Anaspidacea

View on Wikipedia

| Anaspidacea | |

|---|---|

| |

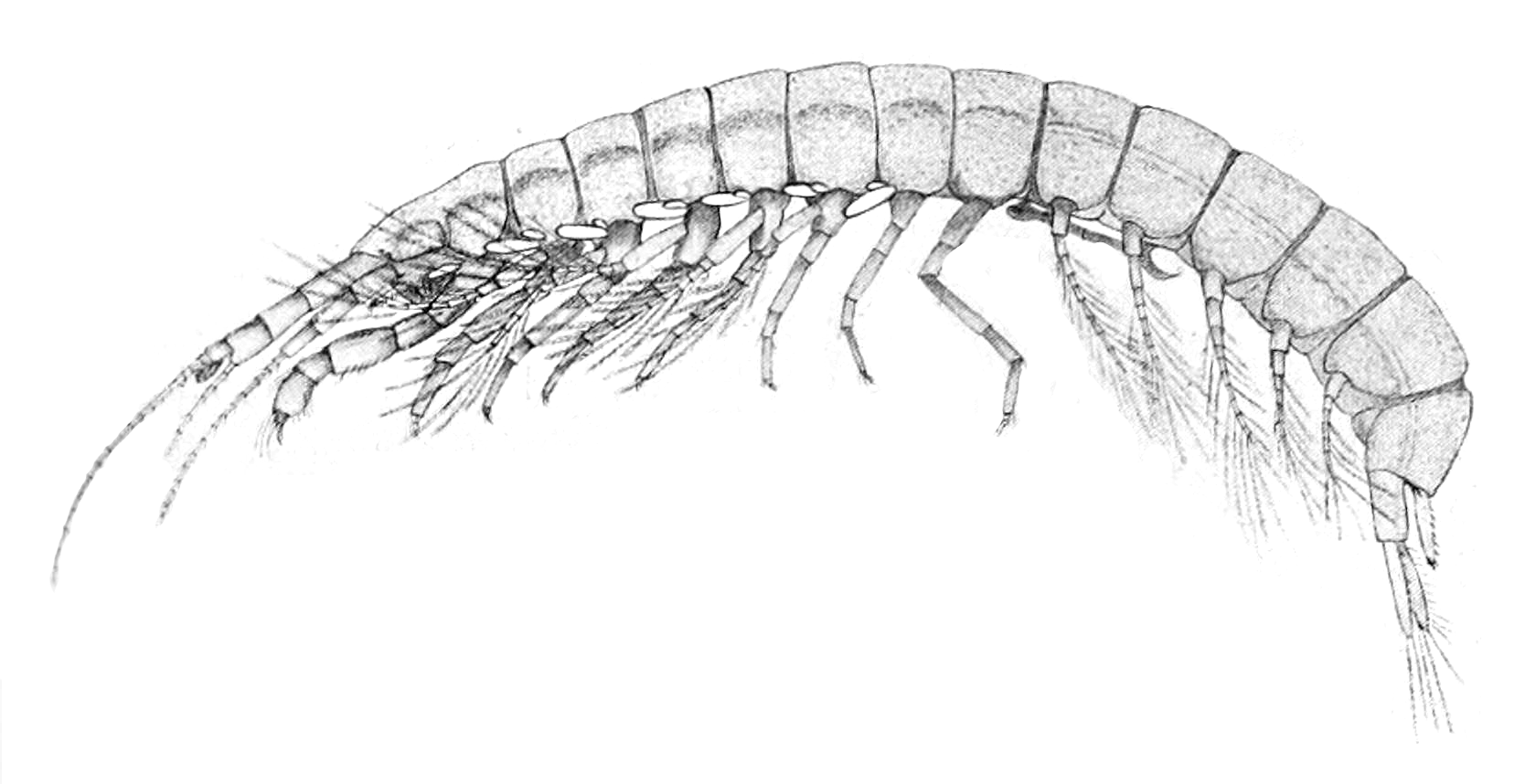

| Koonunga cursor male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Superorder: | Syncarida |

| Order: | Anaspidacea Calman, 1904 |

| Families | |

|

See text | |

Anaspidacea is an order of crustaceans, comprising eleven genera in four families. Species in the family Anaspidesidae vary from being strict stygobionts (only living underground) to species living in lakes, streams and moorland pools, and are found only in Tasmania.[1] Koonungidae is found in Tasmania and the south-eastern part of the Australian mainland, where they live in the burrows made by crayfish and in caves.[2] The families Psammaspididae and Stygocarididae are both restricted to caves, but Stygocarididae has a much wider distribution than the other families, with Parastygocaris having species in New Zealand and South America as well as Australia; two other genera in the family are endemic to South America, and one, Stygocarella, is endemic to New Zealand.[3][4][5]

Genera

[edit]

- Anaspidesidae Ahyong & Alonso-Zarazaga, 2017 (=Anaspididae Thomson, 1893)[6]

- Allanaspides Swain, Wilson, Hickman & Ong, 1970 – Tasmania

- Anaspides Thomson, 1894 – Tasmania

- Paranaspides Smith, 1908 – Tasmania

- Koonungidae Sayce, 1908

- Koonunga Sayce, 1907 – south-eastern Australia and Tasmania

- Micraspides Nicholls, 1931 – south-eastern Australia and Tasmania

- Psammaspididae Schminke, 1974

- Eucrenonaspides Knott & Lake, 1980 – Tasmania

- Psammaspides Schminke, 1974 – south-eastern Australia

- Stygocarididae Noodt, 1963

- Oncostygocaris Schminke, 1980 – southern South America

- Parastygocaris Noodt, 1963 – southern South America

- Stygocarella Schminke, 1980 – New Zealand

- Stygocaris Noodt, 1963 – southern South America, south-eastern Australia and New Zealand

References

[edit]- ^ J. K. Lowry & M. Yerman (October 2, 2002). "Anaspidacea: Families – Anaspididae". Archived from the original on December 13, 2010. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ J. K. Lowry & M. Yerman (October 2, 2002). "Anaspidacea: Families – Koonungidae". Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ Estela C. Lopretto & Juan J. Morrone (1998). "Anaspidacea, Bathynellacea (Crustacea, Syncarida), generalised tracks, and the biogeographical relationships of South America". Zoologica Scripta. 27 (4): 311–318. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.1998.tb00463.x. S2CID 84696879.

- ^ J. K. Lowry & M. Yerman (October 2, 2002). "Anaspidacea: Families – Psammaspididae". Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ J. K. Lowry & M. Yerman (October 2, 2002). "Anaspidacea: Families – Stygocarididae". Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ Shane T. Ahyong; Miguel A. Alonso-Zarazaga (6 September 2017). "Anaspidesidae, a new family for syncarid crustaceans formerly placed in Anaspididae Thomson, 1893" (PDF). Records of the Australian Museum. 69 (4): 257–258. doi:10.3853/J.2201-4349.69.2017.1680. ISSN 0067-1975. Wikidata Q56036674.

Anaspidacea

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy

Families and Genera

The order Anaspidacea was established by Calman in 1904 within the superorder Syncarida of the subclass Malacostraca to include primitive, carapace-lacking crustaceans formerly classified among fossil forms.[8][9] The current classification recognizes four families, 11 genera, and approximately 70 extant species worldwide (with about 21 in Australia), following nomenclatural adjustments including the 2017 elevation of Anaspidesidae from taxa previously in Anaspididae; some synonymies have been resolved in recent revisions, and a 2014 phylogenetic study proposed six families based on morphology, but consensus retains four.[1][3][9] The family Anaspidesidae (derived from the type genus Anaspides, a replacement name for the preoccupied Anaspis) reflects the Greek "anaspis," meaning "shieldless," alluding to the group's diagnostic lack of a carapace; similar etymological roots apply to related family names emphasizing primitive or habitat-specific traits, such as Psammaspididae from "psammos" (sand) for interstitial forms.[9][10] The families and their constituent genera are detailed below, with species counts reflecting recent descriptions and synonymies as of 2025 (e.g., the 2023 description of Anaspides driesseni based on morphological and molecular evidence distinguishing it from A. swaini). Note that while Anaspidesidae, Koonungidae, and Psammaspididae are endemic to Australia (primarily Tasmania), Stygocarididae is cosmopolitan within the order's range and includes additional genera (e.g., Argentostygocaris, Patagonaspilla) and approximately 50 species in South America and New Zealand.| Family | Genera and Species Counts |

|---|---|

| Anaspidesidae | Allanaspides (2 species); Anaspides (9 species, including the 2023 addition A. driesseni); Paranaspides (1 species) — total 12 species, all endemic to Tasmania |

| Koonungidae | Koonunga (1 species) — total 1 species, southeastern Australia and Tasmania |

| Psammaspididae | Psammaspides (1 species) — total 1 species, Tasmania |

| Stygocarididae | Australian genera: Australostygocaris (1 species); Nixtalimon (1 species); Oncostygocaris (1 species); Parastygocaris (2 species); Stygocaris (3 species); Stygocarella (2 species) — total ~10 Australian species; additional ~50 species in 5+ genera elsewhere |