Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

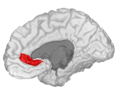

Anterior cingulate cortex

View on Wikipedia

| Anterior cingulate cortex | |

|---|---|

Medial surface of left cerebral hemisphere, with anterior cingulate highlighted | |

Medial surface of right hemisphere, with Brodmann's areas numbered | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cortex cingularis anterior |

| NeuroNames | 161 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_936 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

In human brains, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is the frontal part of the cingulate cortex that resembles a "collar" surrounding the frontal part of the corpus callosum. It consists of Brodmann areas 24, 32, and 33.

It is involved in certain higher-level functions, such as attention allocation,[1] reward anticipation, decision-making, impulse control (e.g. performance monitoring and error detection),[2] and emotion.[3][4]

Some research calls it the anterior midcingulate cortex (aMCC).

Anatomy

[edit]

The anterior cingulate cortex can be divided anatomically based on cognitive (dorsal), and emotional (ventral) components.[5] The dorsal part of the ACC is connected with the prefrontal cortex and parietal cortex, as well as the motor system and the frontal eye fields,[6] making it a central station for processing top-down and bottom-up stimuli and assigning appropriate control to other areas in the brain. By contrast, the ventral part of the ACC is connected with the amygdala, nucleus accumbens, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and anterior insula, and is involved in assessing the salience of emotion and motivational information. The ACC seems to be especially involved when effort is needed to carry out a task, such as in early learning and problem-solving.[7]

On a cellular level, the ACC is unique in its abundance of specialized neurons called spindle cells,[8] or von Economo neurons. These cells are a relatively recent occurrence in evolutionary terms (found only in humans and other primates, cetaceans, and elephants) and contribute to this brain region's emphasis on addressing difficult problems, as well as the pathologies related to the ACC.[9]

Tasks

[edit]A typical task that activates the ACC involves eliciting some form of conflict within the participant that can potentially result in an error. One such task is called the Eriksen flanker task and consists of an arrow pointing to the left or right, which is flanked by two distractor arrows creating either compatible (<<<<<) or incompatible (>><>>) trials.[10] Another very common conflict-inducing stimulus that activates the ACC is the Stroop task, which involves naming the color ink of words that are either congruent (RED written in red) or incongruent (RED written in blue).[11] Conflict occurs because people's reading abilities interfere with their attempt to correctly name the word's ink color. A variation of this task is the Counting-Stroop, during which people count either neutral stimuli ('dog' presented four times) or interfering stimuli ('three' presented four times) by pressing a button. Another version of the Stroop task named the Emotional Counting Stroop is identical to the Counting Stroop test, except that it also uses segmented or repeated emotional words such as "murder" during the interference part of the task. Thus, ACC affects decision making of a task.

Functions

[edit]Many studies attribute specific functions such as error detection, anticipation of tasks, attention,[11][12] motivation, and modulation of emotional responses to the ACC.[5][6][13]

Error detection and conflict monitoring

[edit]The most basic form of ACC theory states that the ACC is involved with error detection.[5] Evidence has been derived from studies involving a Stroop task.[6] However, ACC is also active during correct response, and this has been shown using a letter task, whereby participants had to respond to the letter X after an A was presented and ignore all other letter combinations with some letters more competitive than others.[14] They found that for more competitive stimuli ACC activation was greater.

A similar theory poses that the ACC's primary function is the monitoring of conflict. In Eriksen flanker task, incompatible trials produce the most conflict and the most activation by the ACC. Upon detection of a conflict, the ACC then provides cues to other areas in the brain to cope with the conflicting control systems.

Evidence from electrical studies

[edit]Evidence for ACC as having an error detection function comes from observations of error-related negativity (ERN) uniquely generated within the ACC upon error occurrences.[5][15][16][17] A distinction has been made between an ERP following incorrect responses (response ERN) and a signal after subjects receive feedback after erroneous responses (feedback ERN).

Patients with lateral prefrontal cingulate (PFC) damage show reduced ERNs.[18]

Reinforcement learning ERN theory poses that there is a mismatch between actual response execution and appropriate response execution, which results in an ERN discharge.[5][16] Furthermore, this theory predicts that, when the ACC receives conflicting input from control areas in the brain, it determines and allocates which area should be given control over the motor system. Varying levels of dopamine are believed to influence the optimization of this filter system by providing expectations about the outcomes of an event. The ERN, then, serves as a beacon to highlight the violation of an expectation.[17] Research on the occurrence of the feedback ERN shows evidence that this potential has larger amplitudes when violations of expectancy are large. In other words, if an event is not likely to happen, the feedback ERN will be larger if no error is detected. Other studies have examined whether the ERN is elicited by varying the cost of an error and the evaluation of a response.[16]

In these trials, feedback is given about whether the participant has gained or lost money after a response. Amplitudes of ERN responses with small gains and small losses were similar. No ERN was elicited for any losses as opposed to an ERN for no wins, even though both outcomes are the same. The finding in this paradigm suggests that monitoring for wins and losses is based on the relative expected gains and losses. If you get a different outcome than expected, the ERN will be larger than for expected outcomes. ERN studies have also localized specific functions of the ACC.[17]

The rostral ACC seems to be active after an error commission, indicating an error response function, whereas the dorsal ACC is active after both an error and feedback, suggesting a more evaluative function (for fMRI evidence, see also[19][20][21] ). This evaluation is emotional in nature and highlights the amount of distress associated with a certain error.[5] Summarizing the evidence found by ERN studies, it appears to be the case that ACC receives information about a stimulus, selects an appropriate response, monitors the action, and adapts behavior if there is a violation of expectancy.[17]

Social evaluation

[edit]Activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) has been implicated in processing both the detection and appraisal of social processes, including social exclusion. When exposed to repeated personal social evaluative tasks, non-depressed women showed reduced fMRI BOLD activation in the dACC on the second exposure, while women with a history of depression exhibited enhanced BOLD activation. This differential activity may reflect enhanced rumination about social evaluation or enhanced arousal associated with repeated social evaluation.[22]

The anterior cingulate cortex gyrus is involved in effort to help others.[23]

Reward-based learning theory

[edit]A more comprehensive and recent theory describes the ACC as a more active component and poses that it detects and monitors errors, evaluates the degree of the error, and then suggests an appropriate form of action to be implemented by the motor system. Earlier evidence from electrical studies indicate the ACC has an evaluative component, which is indeed confirmed by fMRI studies. The dorsal and rostral areas of the ACC both seem to be affected by rewards and losses associated with errors. During one study, participants received monetary rewards and losses for correct and incorrect responses, respectively.[19]

Largest activation in the dACC was shown during loss trials. This stimulus did not elicit any errors, and, thus, error detection and monitoring theories cannot fully explain why this ACC activation would occur. The dorsal part of the ACC seems to play a key role in reward-based decision-making and learning. The rostral part of the ACC, on the other hand, is believed to be involved more with affective responses to errors. In an interesting expansion of the previously described experiment, the effects of rewards and costs on ACC's activation during error commission was examined.[21] Participants performed a version of the Eriksen flanker task using a set of letters assigned to each response button instead of arrows.

Targets were flanked by either a congruent or an incongruent set of letters. Using an image of a thumb (up, down, or neutral), participants received feedback on how much money they gained or lost. The researchers found greater rostral ACC activation when participants lost money during the trials. The participants reported being frustrated when making mistakes. Because the ACC is intricately involved with error detection and affective responses, it may very well be that this area forms the basis of self-confidence. Taken together, these findings indicate that both the dorsal and rostral areas are involved in evaluating the extent of the error and optimizing subsequent responses. A study confirming this notion explored the functions of both the dorsal and rostral areas of the ACC involved using a saccade task.[20]

Participants were shown a cue that indicated whether they had to make either a pro-saccade or an anti-saccade. An anti-saccade requires suppression of a distracting cue because the target appears in the opposite location causing the conflict. Results showed differing activation for the rostral and dorsal ACC areas. Early correct anti-saccade performance was associated with rostral activation. The dorsal area, on the other hand, was activated when errors were committed, but also for correct responses.

Whenever the dorsal area was active, fewer errors were committed providing more evidence that the ACC is involved with effortful performance. The second finding showed that, during error trials, the ACC activated later than for correct responses, clearly indicating a kind of evaluative function.

Role in consciousness

[edit]The ACC area in the brain is associated with many functions that are correlated with conscious experience. Greater ACC activation levels were present in more emotionally aware female participants when shown short 'emotional' video clips.[24] Better emotional awareness is associated with improved recognition of emotional cues or targets, which is reflected by ACC activation.

The idea of awareness being associated with the ACC is supported by some evidence, in that it seems to be the case that, when subjects' responses are not congruent with actual responses, a larger error-related negativity is produced.[17]

One study found an ERN even when subjects were not aware of their error.[17] Awareness may not be necessary to elicit an ERN, but it could influence the effect of the amplitude of the feedback ERN. Relating to the reward-based learning theory, awareness could modulate expectancy violations. Increased awareness could result in decreased violations of expectancies and decreased awareness could achieve the opposite effect. Further research is needed to completely understand the effects of awareness on ACC activation.

In The Astonishing Hypothesis, Francis Crick identifies the anterior cingulate, to be specific the anterior cingulate sulcus, as a likely candidate for the center of free will in humans. Crick bases this suggestion on scans of patients with specific lesions that seem to interfere with their sense of independent will, such as alien hand syndrome.

Role in registering pain

[edit]The ACC registers physical pain as shown in functional MRI studies that showed an increase in signal intensity, typically in the posterior part of area 24 of the ACC, that was correlated with pain intensity. When this pain-related activation was accompanied by attention-demanding cognitive tasks (verbal fluency), the attention-demanding tasks increased signal intensity in a region of the ACC anterior and/or superior to the pain-related activation region.[25] The ACC is the cortical area that has been most frequently linked to the experience of pain.[26] It appears to be involved in the emotional reaction to pain rather than to the perception of pain itself.[27]

Evidence from social neuroscience studies have suggested that, in addition to its role in physical pain, the ACC may also be involved in monitoring painful social situations as well, such as exclusion or rejection. When participants felt socially excluded in an fMRI virtual ball throwing game in which the ball was never thrown to the participant, the ACC showed activation. Further, this activation was correlated with a self-reported measure of social distress, indicating that the ACC may be involved in the detection and monitoring of social situations which may cause social/emotional pain, rather than just physical pain.[28]

Pathology

[edit]Studying the effects of damage to the ACC provides insights into the type of functions it serves in the intact brain. Behavior that is associated with lesions in the ACC includes: inability to detect errors, severe difficulty with resolving stimulus conflict in a Stroop task, emotional instability, inattention, and akinetic mutism.[29][5][6] There is evidence that damage to ACC is present in patients with schizophrenia, where studies have shown patients have difficulty in dealing with conflicting spatial locations in a Stroop-like task and having abnormal ERNs.[6][16] Participants with ADHD were found to have reduced activation in the dorsal area of the ACC when performing the Stroop task.[30] Together, these findings corroborate results from imaging and electrical studies about the variety of functions attributed to the ACC.

OCD

[edit]There is strong evidence that this area may have a role in obsessive–compulsive disorder. A recent study from the University of Cambridge showed that participants with OCD had higher levels of glutamate and lower levels of GABA in the anterior cingulate cortex, compared to participants without OCD. They used magnetic resonance spectroscopy to assess the balance of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission by measuring glutamate and GABA levels in anterior cingulate cortex and supplementary motor area of healthy volunteers and participants with OCD. Participants with OCD had significantly higher levels of glutamate and lower levels of GABA in the ACC and a higher Glu:GABA ratio in that region.[31]

Recent SDM meta-analyses of voxel-based morphometry studies comparing people with OCD and healthy controls has found people with OCD to have increased grey matter volumes in bilateral lenticular nuclei, extending to the caudate nuclei, while decreased grey matter volumes in bilateral dorsal medial frontal/anterior cingulate cortex.[32][33] These findings contrast with those in people with other anxiety disorders, who evince decreased (rather than increased) grey matter volumes in bilateral lenticular / caudate nuclei, while also decreased grey matter volumes in bilateral dorsal medial frontal / anterior cingulate gyri.[33]

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders

[edit]In individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, the anterior cingulate cortex has been found to be smaller compared to that of control subjects.[34][35] Meta-analyses have shown that its activity is reduced during emotion processing,[36] and its functional connectivity with the striatum is diminished at rest, which has been linked to cognitive rigidity.[37]

Anxiety

[edit]The ACC has been suggested to have possible links with social anxiety, along with the amygdala part of the brain, but this research is still in its early stages.[38] A more recent study, by the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Centre, confirms the relationship between the ACC and anxiety regulation, by revealing mindfulness practice as a meditator for anxiety precisely through the ACC.[39]

Depression

[edit]The adjacent subcallosal cingulate gyrus has been implicated in major depression and research indicates that deep-brain stimulation of the region could act to alleviate depressive symptoms.[40] Although people with depression had smaller subgenual ACCs,[41] their ACCs were more active when adjusted for size. This correlates well with increased subgenual ACC activity during sadness in healthy people,[42] and normalization of activity after successful treatment.[43] Of note, the activity of the subgenual cingulate cortex correlates with individual differences in negative affect during the baseline resting state; in other words, the greater the subgenual activity, the greater the negative affectivity in temperament.[44]

Lead exposure

[edit]A study of brain MRIs taken on adults that had previously participated in the Cincinnati Lead Study found that people that had higher levels of lead exposure as children had decreased brain size as adults. This effect was most pronounced in the ACC (Cecil et al., 2008)[45] and is thought to relate to the cognitive and behavioral deficits of affected individuals.

Autism

[edit]Impairments in the development of the anterior cingulate, together with impairments in the dorsal medial-frontal cortex, may constitute a neural substrate for socio-cognitive deficits in autism, such as social orienting and joint attention.[46]

PTSD

[edit]An increasing number of studies are investigating the role of the ACC in post-traumatic stress disorder. PTSD diagnosis and related symptoms such as skin conductance response (SCR) to "potentially startling sounds" were found to be correlated with reduced ACC volume.[47] Further, childhood trauma and executive dysfunction seem to correlate with reduced ACC connectivity to surrounding neural regions.[48] In a longitudinal study, this reduced connectivity was able to predict high-risk drinking (binge drinking at least once per week for the past 12 months) up to four years later.[48]

General risk of psychopathology

[edit]A study on differences in brain structure of adults with high and low levels of cognitive-attentional syndrome demonstrated diminished volume of the dorsal part of the ACC in the former group, indicating relationship between cortical thickness of ACC and general risk of psychopathology.[49]

Additional images

[edit]-

Medial surface of human cerebral cortex - gyri

-

Anterior Cingulate Cortex of monkey (Macaca mulatta).

-

Caudal Anterior Cingulate gyrus

-

Rostral Anterior Cingulate gyrus

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pardo JV, Pardo PJ, Janer KW, Raichle ME (January 1990). "The anterior cingulate cortex mediates processing selection in the Stroop attentional conflict paradigm". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (1): 256–9. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87..256P. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.1.256. PMC 53241. PMID 2296583.

- ^ Hewitt J (26 March 2013). "Predicting repeat offenders with brain scans: You be the judge". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ Decety J, Jackson PL (June 2004). "The functional architecture of human empathy". Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 3 (2): 71–100. doi:10.1177/1534582304267187. PMID 15537986. S2CID 145310279.

- ^ Jackson PL, Brunet E, Meltzoff AN, Decety J (2006). "Empathy examined through the neural mechanisms involved in imagining how I feel versus how you feel pain" (PDF). Neuropsychologia. 44 (5): 752–61. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.333.2783. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.07.015. PMID 16140345. S2CID 6848345. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bush G, Luu P, Posner MI (June 2000). "Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 4 (6): 215–222. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01483-2. PMID 10827444. S2CID 16451230.

- ^ a b c d e Posner MI, DiGirolamo GJ (1998). "Executive attention: Conflict, target detection, and cognitive control". In Parasuraman R (ed.). The attentive brain. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-16172-9.

- ^ Allman JM, Hakeem A, Erwin JM, Nimchinsky E, Hof P (May 2001). "The anterior cingulate cortex. The evolution of an interface between emotion and cognition". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 935 (1): 107–17. Bibcode:2001NYASA.935..107A. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03476.x. PMID 11411161. S2CID 10507342.

- ^ Carter R. The Human Brain Book. p. 124.

- ^ Allman JM, Hakeem A, Erwin JM, Nimchinsky E, Hof P (May 2001). "The anterior cingulate cortex. The evolution of an interface between emotion and cognition". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 935 (1): 107–17. Bibcode:2001NYASA.935..107A. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03476.x. PMID 11411161. S2CID 10507342.

- ^ Botvinick M, Nystrom LE, Fissell K, Carter CS, Cohen JD (November 1999). "Conflict monitoring versus selection-for-action in anterior cingulate cortex". Nature. 402 (6758): 179–81. Bibcode:1999Natur.402..179B. doi:10.1038/46035. PMID 10647008. S2CID 4425726.

- ^ a b Pardo JV, Pardo PJ, Janer KW, Raichle ME (January 1990). "The anterior cingulate cortex mediates processing selection in the Stroop attentional conflict paradigm". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (1): 256–9. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87..256P. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.1.256. PMC 53241. PMID 2296583.

- ^ Weissman DH, Gopalakrishnan A, Hazlett CJ, Woldorff MG (February 2005). "Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex resolves conflict from distracting stimuli by boosting attention toward relevant events". Cerebral Cortex. 15 (2): 229–37. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhh125. PMID 15238434.

- ^ Nieuwenhuis S, Ridderinkhof KR, Blom J, Band GP, Kok A (September 2001). "Error-related brain potentials are differentially related to awareness of response errors: evidence from an antisaccade task". Psychophysiology. 38 (5): 752–60. doi:10.1111/1469-8986.3850752. PMID 11577898. S2CID 7566915.

- ^ Carter CS, Braver TS, Barch DM, Botvinick MM, Noll D, Cohen JD (May 1998). "Anterior cingulate cortex, error detection, and the online monitoring of performance". Science. 280 (5364): 747–9. Bibcode:1998Sci...280..747C. doi:10.1126/science.280.5364.747. PMID 9563953. S2CID 264267292.

- ^ Gehring WJ, Goss B, Coles MG, Meyer DE, Donchin E (November 1993). "A neural system for error-detection and compensation". Psychological Science. 4 (6): 385–90. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1993.tb00586.x. S2CID 17422146.

- ^ a b c d Holroyd CB, Nieuwenhuis S, Mars RB, Coles MG (2004). "Anterior cingulate cortex, selection for action, and error processing". In Posner MI (ed.). Cognitive neuroscience of attention. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 219–31. ISBN 1-59385-048-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Luu P, Pederson SM (2004). "The anterior cingulate cortex: Regulating actions in context". In Posner MI (ed.). Cognitive neuroscience of attention. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 1-59385-048-4.

- ^ Gehring WJ, Knight RT (May 2000). "Prefrontal-cingulate interactions in action monitoring". Nature Neuroscience. 3 (5): 516–20. doi:10.1038/74899. PMID 10769394. S2CID 11136447.

- ^ a b Bush G, Vogt BA, Holmes J, Dale AM, Greve D, Jenike MA, Rosen BR (January 2002). "Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex: a role in reward-based decision making". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (1): 523–8. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99..523B. doi:10.1073/pnas.012470999. PMC 117593. PMID 11756669.

- ^ a b Polli FE, Barton JJ, Cain MS, Thakkar KN, Rauch SL, Manoach DS (October 2005). "Rostral and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex make dissociable contributions during antisaccade error commission". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (43): 15700–5. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10215700P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503657102. PMC 1255733. PMID 16227444.

- ^ a b Taylor SF, Martis B, Fitzgerald KD, Welsh RC, Abelson JL, Liberzon I, Himle JA, Gehring WJ (April 2006). "Medial frontal cortex activity and loss-related responses to errors". The Journal of Neuroscience. 26 (15): 4063–70. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4709-05.2006. PMC 6673891. PMID 16611823.

- ^ Dedovic K, Slavich GM, Muscatell KA, Irwin MR, Eisenberger NI (2016). "Dorsal Anterior Cingulate Cortex Responses to Repeated Social Evaluative Feedback in Young Women with and without a History of Depression". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 10: 64. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00064. PMC 4815251. PMID 27065828.

- ^ "When Can We Be Bothered to Help Others? Brain Region Responsible for This Behavior Discovered". 26 August 2022.

- ^ Lane RD, Reiman EM, Axelrod B, Yun LS, Holmes A, Schwartz GE (July 1998). "Neural correlates of levels of emotional awareness. Evidence of an interaction between emotion and attention in the anterior cingulate cortex". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 10 (4): 525–35. doi:10.1162/089892998562924. PMID 9712681. S2CID 27743177.

- ^ Davis, Karen D., Stephen J. Taylor, Adrian P. Crawley, Michael L. Wood, and David J. Mikulis. "Functional MRI of pain- and attention-related activations in the human cingulate cortex", J. Neurophysiol. volume 77: pages 3370–3380, 1997 [1]

- ^ Pinel JP (2011). Biopsychology (8th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-205-83256-9.

- ^ Price DD (June 2000). "Psychological and neural mechanisms of the affective dimension of pain". Science. 288 (5472): 1769–72. Bibcode:2000Sci...288.1769P. doi:10.1126/science.288.5472.1769. PMID 10846154. S2CID 15250446.

- ^ Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, Williams KD (October 2003). "Does rejection hurt? An FMRI study of social exclusion". Science. 302 (5643): 290–2. Bibcode:2003Sci...302..290E. doi:10.1126/science.1089134. PMID 14551436. S2CID 21253445.

- ^ Janer KW, Pardo JV (1991). "Deficits in selective attention following bilateral anterior cingulotomy". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 3 (3): 231–41. doi:10.1162/jocn.1991.3.3.231. PMID 23964838. S2CID 39599951.

- ^ Bush G, Frazier JA, Rauch SL, Seidman LJ, Whalen PJ, Jenike MA, Rosen BR, Biederman J (June 1999). "Anterior cingulate cortex dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder revealed by fMRI and the Counting Stroop". Biological Psychiatry. 45 (12): 1542–52. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00083-9. PMID 10376114. S2CID 205870638.

- ^ Biria, Marjan; Banca, Paula; Healy, Máiréad P.; Keser, Engin; Sawiak, Stephen J.; Rodgers, Christopher T.; Rua, Catarina; de Souza, Ana Maria Frota Lisbôa Pereira; Marzuki, Aleya A.; Sule, Akeem; Ersche, Karen D.; Robbins, Trevor W. (27 June 2023). "Cortical glutamate and GABA are related to compulsive behaviour in individuals with obsessive compulsive disorder and healthy controls". Nature Communications. 14 (1): 3324. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.3324B. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-38695-z. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 10300066. PMID 37369695.

- ^ Radua J, Mataix-Cols D (November 2009). "Voxel-wise meta-analysis of grey matter changes in obsessive-compulsive disorder". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 195 (5): 393–402. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055046. PMID 19880927.

- ^ a b Radua J, van den Heuvel OA, Surguladze S, Mataix-Cols D (July 2010). "Meta-analytical comparison of voxel-based morphometry studies in obsessive-compulsive disorder vs other anxiety disorders". Archives of General Psychiatry. 67 (7): 701–11. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.70. PMID 20603451.

- ^ Haznedar, M. M.; Buchsbaum, M. S.; Hazlett, E. A.; Shihabuddin, L.; New, A.; Siever, L. J. (2004). "Cingulate gyrus volume and metabolism in the schizophrenia spectrum". Schizophrenia Research. 71 (2–3): 249–262. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.02.025. PMID 15474896. S2CID 28889346.

- ^ Fujiwara, H.; Hirao, K.; Namiki, C.; Yamada, M.; Shimizu, M.; Fukuyama, H.; Hayashi, T.; Murai, T. (2007). "Anterior cingulate pathology and social cognition in schizophrenia: A study of gray matter, white matter and sulcal morphometry" (PDF). NeuroImage. 36 (4): 1236–1245. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.068. hdl:2433/124279. PMID 17524666. S2CID 25750603.

- ^ Taylor, S-F; Kang, J; Brege, I-S; Tso, I-F; Hosanagar, A; Johnson, T (15 January 2012). "Meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of emotion perception and experience in schizophrenia". Biological Psychiatry. 71 (2): 136–145. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.09.007. PMC 3237865. PMID 21993193.

- ^ Grimaldi, D-A; Patane', A; Cattarinussi, G; Sambataro, F (2 May 2025). "Functional connectivity of the striatum in psychosis: Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies and replication on an independent sample". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 174. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106179. PMID 40288705.

- ^ Lieberman MD, Eisenberger NI (February 2009). "Neuroscience. Pains and pleasures of social life". Science. 323 (5916): 890–1. doi:10.1126/science.1170008. PMID 19213907. S2CID 206518219.

- ^ Zeidan F, Martucci KT, Kraft RA, McHaffie JG, Coghill RC (June 2014). "Neural correlates of mindfulness meditation-related anxiety relief". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 9 (6): 751–9. doi:10.1093/scan/nst041. PMC 4040088. PMID 23615765.

- ^ Hamani C, Mayberg H, Stone S, Laxton A, Haber S, Lozano AM (February 2011). "The subcallosal cingulate gyrus in the context of major depression". Biological Psychiatry. 69 (4): 301–8. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.034. PMID 21145043. S2CID 35458273.

- ^ Ongür D, Ferry AT, Price JL (June 2003). "Architectonic subdivision of the human orbital and medial prefrontal cortex". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 460 (3): 425–49. doi:10.1002/cne.10609. PMID 12692859. S2CID 9798173.

- ^ George MS, Ketter TA, Parekh PI, Horwitz B, Herscovitch P, Post RM (March 1995). "Brain activity during transient sadness and happiness in healthy women". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 152 (3): 341–51. doi:10.1176/ajp.152.3.341. PMID 7864258.

- ^ Licinio J, Wong ML (29 January 2008). Biology of Depression: From Novel Insights to Therapeutic Strategies. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. pp. 425–466. ISBN 9783527307852.

- ^ Zald DH, Mattson DL, Pardo JV (February 2002). "Brain activity in ventromedial prefrontal cortex correlates with individual differences in negative affect". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (4): 2450–4. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.2450Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.042457199. PMC 122385. PMID 11842195.

- ^ Cecil KM, Brubaker CJ, Adler CM, Dietrich KN, Altaye M, Egelhoff JC, Wessel S, Elangovan I, Hornung R, Jarvis K, Lanphear BP (May 2008). "Decreased brain volume in adults with childhood lead exposure". PLOS Medicine. 5 (5): e112. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050112. PMC 2689675. PMID 18507499.

- ^ Peter Mundy (2003). "Annotation: The neural basis of social impairments in autism: the role of the dorsal medial-frontal cortex and anterior cingulate system" (PDF). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 44 (6): 793–809. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00165. PMID 12959489. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2012.

- ^ Young DA, Chao L, Neylan TC, O'Donovan A, Metzler TJ, Inslicht SS (November 2018). "Association among anterior cingulate cortex volume, psychophysiological response, and PTSD diagnosis in a Veteran sample". Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 155: 189–196. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2018.08.006. PMC 6361720. PMID 30086395.

- ^ a b Silveira S, Shah R, Nooner KB, Nagel BJ, Tapert SF, de Bellis MD, Mishra J (May 2020). "Impact of Childhood Trauma on Executive Function in Adolescence-Mediating Functional Brain Networks and Prediction of High-Risk Drinking". Biological Psychiatry. Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. 5 (5): 499–509. doi:10.1016/j.bpsc.2020.01.011. PMC 8366521. PMID 32299789.

- ^ Kowalski, Joachim; Wypych, Marek; Marchewka, Artur; Dragan, Małgorzata (10 March 2022). "Brain structural correlates of cognitive-attentional syndrome – a Voxel-Based Morphometry Study". Brain Imaging and Behavior. 16 (4): 1914–1918. doi:10.1007/s11682-022-00649-2. ISSN 1931-7565. PMID 35266100. S2CID 247360689.