Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Reward system

View on Wikipedia

The reward system (the mesocorticolimbic circuit) is a group of neural structures responsible for incentive salience (i.e., "wanting"; desire or craving for a reward and motivation), associative learning (primarily positive reinforcement and classical conditioning), and positively-valenced emotions, particularly ones involving pleasure as a core component (e.g., joy, euphoria and ecstasy).[2][3] Reward is the attractive and motivational property of a stimulus that induces appetitive behavior, also known as approach behavior, and consummatory behavior.[2] A rewarding stimulus has been described as "any stimulus, object, event, activity, or situation that has the potential to make us approach and consume it is by definition a reward".[2] In operant conditioning, rewarding stimuli function as positive reinforcers;[1] however, the converse statement also holds true: positive reinforcers are rewarding.[1][4] The reward system motivates animals to approach stimuli or engage in behaviour that increases fitness (sex, energy-dense foods, etc.). Survival for most animal species depends upon maximizing contact with beneficial stimuli and minimizing contact with harmful stimuli. Reward cognition serves to increase the likelihood of survival and reproduction by causing associative learning, eliciting approach and consummatory behavior, and triggering positively-valenced emotions.[1] Thus, reward is a mechanism that evolved to help increase the adaptive fitness of animals.[5] In drug addiction, certain substances over-activate the reward circuit, leading to compulsive substance-seeking behavior resulting from synaptic plasticity in the circuit.[6]

Primary rewards are a class of rewarding stimuli which facilitate the survival of one's self and offspring, and they include homeostatic (e.g., palatable food) and reproductive (e.g., sexual contact and parental investment) rewards.[2][7] Intrinsic rewards are unconditioned rewards that are attractive and motivate behavior because they are inherently pleasurable.[2] Extrinsic rewards (e.g., money or seeing one's favorite sports team winning a game) are conditioned rewards that are attractive and motivate behavior but are not inherently pleasurable.[2][8] Extrinsic rewards derive their motivational value as a result of a learned association (i.e., conditioning) with intrinsic rewards.[2] Extrinsic rewards may also elicit pleasure (e.g., euphoria from winning a lot of money in a lottery) after being classically conditioned with intrinsic rewards.[2]

Definition

[edit]In neuroscience, the reward system is a collection of brain structures and neural pathways that are responsible for reward-related cognition, including associative learning (primarily classical conditioning and operant reinforcement), incentive salience (i.e., motivation and "wanting", desire, or craving for a reward), and positively-valenced emotions, particularly emotions that involve pleasure (i.e., hedonic "liking").[1][3]

Reward related activities, such as feeding, exercise, sex, substance use, and social interactions play a factor in elevated levels of dopamine, ultimately altering the CNS (or the central nervous system). Dopamine is the chemical messenger that plays a role in regulating mood, motivation, reward, and pleasure.[9]

Terms that are commonly used to describe behavior related to the "wanting" or desire component of reward include appetitive behavior, approach behavior, preparatory behavior, instrumental behavior, anticipatory behavior, and seeking.[10] Terms that are commonly used to describe behavior related to the "liking" or pleasure component of reward include consummatory behavior and taking behavior.[10]

The three primary functions of rewards are their capacity to:

- produce associative learning (i.e., classical conditioning and operant reinforcement);[1]

- affect decision-making and induce approach behavior (via the assignment of motivational salience to rewarding stimuli);[1]

- elicit positively-valenced emotions, particularly pleasure.[1]

Neuroanatomy

[edit]Overview

[edit]The brain structures that compose the reward system are located primarily within the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop;[11] the basal ganglia portion of the loop drives activity within the reward system.[11] Most of the pathways that connect structures within the reward system are glutamatergic interneurons, GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSNs), and dopaminergic projection neurons,[11][12] although other types of projection neurons contribute (e.g., orexinergic projection neurons). The reward system includes the ventral tegmental area, ventral striatum (i.e., the nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle), dorsal striatum (i.e., the caudate nucleus and putamen), substantia nigra (i.e., the pars compacta and pars reticulata), prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, insular cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus (particularly, the orexinergic nucleus in the lateral hypothalamus), thalamus (multiple nuclei), subthalamic nucleus, globus pallidus (both external and internal), ventral pallidum, parabrachial nucleus, amygdala, and the remainder of the extended amygdala.[3][11][13][14][15] The dorsal raphe nucleus and cerebellum appear to modulate some forms of reward-related cognition (i.e., associative learning, motivational salience, and positive emotions) and behaviors as well.[16][17][18] The laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (LDT), pedunculopontine nucleus (PPTg), and lateral habenula (LHb) (both directly and indirectly via the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg)) are also capable of inducing aversive salience and incentive salience through their projections to the ventral tegmental area (VTA).[19] The LDT and PPTg both send glutaminergic projections to the VTA that synapse on dopaminergic neurons, both of which can produce incentive salience. The LHb sends glutaminergic projections, the majority of which synapse on GABAergic RMTg neurons that in turn drive inhibition of dopaminergic VTA neurons, although some LHb projections terminate on VTA interneurons. These LHb projections are activated both by aversive stimuli and by the absence of an expected reward, and excitation of the LHb can induce aversion.[20][21][22]

Most of the dopamine pathways (i.e., neurons that use the neurotransmitter dopamine to communicate with other neurons) that project out of the ventral tegmental area are part of the reward system;[11] in these pathways, dopamine acts on D1-like receptors or D2-like receptors to either stimulate (D1-like) or inhibit (D2-like) the production of cAMP.[23] The GABAergic medium spiny neurons of the striatum are components of the reward system as well.[11] The glutamatergic projection nuclei in the subthalamic nucleus, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, and amygdala connect to other parts of the reward system via glutamate pathways.[11] The medial forebrain bundle, which is a set of many neural pathways that mediate brain stimulation reward (i.e., reward derived from direct electrochemical stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus), is also a component of the reward system.[24]

Development of dopamine pathways is of particular importance in adolescents. There are a number of reward-associated behaviors that arise during adolescence partly due to developments of the DA reward system.[25] D1 and D2 receptors peak in adolescence as a result on neural maturation processes including synaptic pruning which can result in altered reward sensitivity.[26]

Two theories exist with regard to the activity of the nucleus accumbens and the generation liking and wanting. The inhibition (or hyperpolarization) hypothesis proposes that the nucleus accumbens exerts tonic inhibitory effects on downstream structures such as the ventral pallidum, hypothalamus or ventral tegmental area, and that in inhibiting MSNs in the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), these structures are excited, "releasing" reward related behavior. While GABA receptor agonists are capable of eliciting both "liking" and "wanting" reactions in the nucleus accumbens, glutaminergic inputs from the basolateral amygdala, ventral hippocampus, and medial prefrontal cortex can drive incentive salience. Furthermore, while most studies find that NAcc neurons reduce firing in response to reward, a number of studies find the opposite response. This had led to the proposal of the disinhibition (or depolarization) hypothesis, that proposes that excitation or NAcc neurons, or at least certain subsets, drives reward related behavior.[3][27][28]

After nearly 50 years of research on brain-stimulation reward, experts have certified that dozens of sites in the brain will maintain intracranial self-stimulation. Regions include the lateral hypothalamus and medial forebrain bundles, which are especially effective. Stimulation there activates fibers that form the ascending pathways; the ascending pathways include the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, which projects from the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens. There are several explanations as to why the mesolimbic dopamine pathway is central to circuits mediating reward. First, there is a marked increase in dopamine release from the mesolimbic pathway when animals engage in intracranial self-stimulation.[5] Second, experiments consistently indicate that brain-stimulation reward stimulates the reinforcement of pathways that are normally activated by natural rewards, and drug reward or intracranial self-stimulation can exert more powerful activation of central reward mechanisms because they activate the reward center directly rather than through the peripheral nerves.[5][29][30] Third, when animals are administered addictive drugs or engage in naturally rewarding behaviors, such as feeding or sexual activity, there is a marked release of dopamine within the nucleus accumbens.[5] However, dopamine is not the only reward compound in the brain.

Key pathway

[edit]

Ventral tegmental area

- The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is important in responding to stimuli and cues that indicate a reward is present. Rewarding stimuli (and all addictive drugs) act on the circuit by triggering the VTA to release dopamine signals to the nucleus accumbens, either directly or indirectly.[citation needed] The VTA has two important pathways: The mesolimbic pathway projecting to limbic (striatal) regions and underpinning the motivational behaviors and processes, and the mesocortical pathway projecting to the prefrontal cortex, underpinning cognitive functions, such as learning external cues, etc.[31]

- Dopaminergic neurons in this region converts the amino acid tyrosine into DOPA using the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, which is then converted to dopamine using the enzyme DOPA decarboxylase.[32]

Striatum (Nucleus Accumbens)

- The striatum is broadly involved in acquiring and eliciting learned behaviors in response to a rewarding cue. The VTA projects to the striatum, and activates the GABA-ergic Medium Spiny Neurons via D1 and D2 receptors within the ventral (Nucleus Accumbens) and dorsal striatum.[33]

- The Ventral Striatum (the Nucleus Accumbens) is broadly involved in acquiring behavior when fed into by the VTA, and eliciting behavior when fed into by the PFC. The NAc shell projects to the pallidum and the VTA, regulating limbic and autonomic functions. This modulates the reinforcing properties of stimuli, and short term aspects of reward. The NAc Core projects to the substantia nigra and is involved in the development of reward-seeking behaviors and its expression. It is involved in spatial learning, conditional response, and impulsive choice; the long term elements of reward.[31]

- The Dorsal Striatum is involved in learning, the Dorsal Medial Striatum in goal directed learning, and the Dorsal Lateral Striatum in stimulus-response learning foundational to Pavlovian response.[34] On repeated activation by a stimuli, the Nucleus Accumbens can activate the Dorsal Striatum via an intrastriatal loop. The transition of signals from the NAc to the DS allows reward associated cues to activate the DS without the reward itself being present. This can activate cravings and reward-seeking behaviors (and is responsible for triggering relapse during abstinence in addiction).[35]

Prefrontal Cortex

- The VTA dopaminergic neurons project to the PFC, activating glutaminergic neurons that project to multiple other regions, including the Dorsal Striatum and NAc, ultimately allowing the PFC to mediate salience and conditional behaviors in response to stimuli.[35]

- Notably, abstinence from addicting drugs activates the PFC, glutamatergic projection to the NAc, which leads to strong cravings, and modulates reinstatement of addiction behaviors resulting from abstinence. The PFC also interacts with the VTA through the mesocortical pathway, and helps associate environmental cues with the reward.[35]

- There are several parts of the brain related to the prefrontal cortex that help with decision-making in different ways. The dACC (dorsal anterior cingulate cortex) tracks effort, conflict, and mistakes. The vmPFC (ventromedial prefrontal cortex) focuses on what feels rewarding and helps make choices based on personal preferences. The OFC (orbitofrontal cortex) evaluates options and predicts their outcomes to guide decisions. Together, they work with dopamine signals to process rewards and actions.[36]

Hippocampus

- The Hippocampus has multiple functions, including in the creation and storage of memories. In the reward circuit, it serves to contextual memories and associated cues. It ultimately underpins the reinstatement of reward-seeking behaviors via cues, and contextual triggers.[37]

Amygdala

- The AMY receives input from the VTA, and outputs to the NAc. The amygdala is important in creating powerful emotional flashbulb memories, and likely underpins the creation of strong cue-associated memories.[38] It also is important in mediating the anxiety effects of withdrawal, and increased drug intake in addiction.[39]

Pleasure centers

[edit]

Pleasure is a component of reward, but not all rewards are pleasurable (e.g., money does not elicit pleasure unless this response is conditioned).[2] Stimuli that are naturally pleasurable, and therefore attractive, are known as intrinsic rewards, whereas stimuli that are attractive and motivate approach behavior, but are not inherently pleasurable, are termed extrinsic rewards.[2] Extrinsic rewards (e.g., money) are rewarding as a result of a learned association with an intrinsic reward.[2] In other words, extrinsic rewards function as motivational magnets that elicit "wanting", but not "liking" reactions once they have been acquired.[2]

The reward system contains pleasure centers or hedonic hotspots – i.e., brain structures that mediate pleasure or "liking" reactions from intrinsic rewards. As of October 2017,[update] hedonic hotspots have been identified in subcompartments within the nucleus accumbens shell, ventral pallidum, parabrachial nucleus, orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), and insular cortex.[3][15][40] The raphe nucleus has also been implicated.[41] The hotspot within the nucleus accumbens shell is located in the rostrodorsal quadrant of the medial shell, while the hedonic coldspot is located in a more posterior region. The posterior ventral pallidum also contains a hedonic hotspot, while the anterior ventral pallidum contains a hedonic coldspot. In rats, microinjections of opioids, endocannabinoids, and orexin are capable of enhancing liking reactions in these hotspots.[3] The hedonic hotspots located in the anterior OFC and posterior insula have been demonstrated to respond to orexin and opioids in rats, as has the overlapping hedonic coldspot in the anterior insula and posterior OFC.[40] On the other hand, the parabrachial nucleus hotspot has only been demonstrated to respond to benzodiazepine receptor agonists.[3]

Hedonic hotspots are functionally linked, in that activation of one hotspot results in the recruitment of the others, as indexed by the induced expression of c-Fos, an immediate early gene. Furthermore, inhibition of one hotspot results in the blunting of the effects of activating another hotspot.[3][40] Therefore, the simultaneous activation of every hedonic hotspot within the reward system is believed to be necessary for generating the sensation of an intense euphoria.[42]

Wanting and liking

[edit]

Incentive salience is the "wanting" or "desire" attribute, which includes a motivational component, that is assigned to a rewarding stimulus by the nucleus accumbens shell (NAcc shell).[2][43][44] The degree of dopamine neurotransmission into the NAcc shell from the mesolimbic pathway is highly correlated with the magnitude of incentive salience for rewarding stimuli.[43]

Activation of the dorsorostral region of the nucleus accumbens correlates with increases in wanting without concurrent increases in liking.[45] However, dopaminergic neurotransmission into the nucleus accumbens shell is responsible not only for appetitive motivational salience (i.e., incentive salience) towards rewarding stimuli, but also for aversive motivational salience, which directs behavior away from undesirable stimuli.[10][46][47] In the dorsal striatum, activation of D1 expressing MSNs produces appetitive incentive salience, while activation of D2 expressing MSNs produces aversion. In the NAcc, such a dichotomy is not as clear cut, and activation of both D1 and D2 MSNs is sufficient to enhance motivation,[48][49] likely via disinhibiting the VTA through inhibiting the ventral pallidum.[50][51]

Terry Robinson and Kent Berridge's 1993 incentive-sensitization theory proposed that reward contains separable psychological components: wanting (incentive) and liking (pleasure).[52] To explain increasing contact with a certain stimulus such as chocolate, there are two independent factors at work – our desire to have the chocolate (wanting) and the pleasure effect of the chocolate (liking). According to Robinson and Berridge, wanting and liking are two aspects of the same process, so rewards are usually wanted and liked at the same time. However, wanting and liking also change independently under certain circumstances. For example, rats that do not eat after receiving dopamine (experiencing a loss of desire for food) act as though they still like food. In another example, activated self-stimulation electrodes in the lateral hypothalamus of rats increase appetite, but also cause more adverse reactions to tastes such as sugar and salt; apparently, the stimulation increases wanting but not liking. Such results demonstrate that the reward system of rats includes independent processes of wanting and liking. The wanting component is thought to be controlled by dopaminergic pathways, whereas the liking component is thought to be controlled by opiate-GABA-endocannabinoids systems.[5]

Anti-reward system

[edit]Koobs & Le Moal proposed that there exists a separate circuit responsible for the attenuation of reward-pursuing behavior, which they termed the anti-reward circuit. This component acts as brakes on the reward circuit, thus preventing the over pursuit of food, sex, etc. This circuit involves multiple parts of the amygdala (the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, the central nucleus), the Nucleus Accumbens, and signal molecules including norepinephrine, corticotropin-releasing factor, and dynorphin.[53] This circuit is also hypothesized to mediate the unpleasant components of stress, and is thus thought to be involved in addiction and withdrawal. While the reward circuit mediates the initial positive reinforcement involved in the development of addiction, it is the anti-reward circuit that later dominates via negative reinforcement that motivates the pursuit of the rewarding stimuli.[54]

Learning

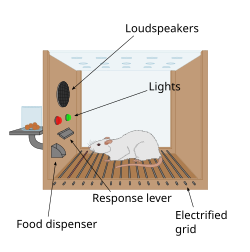

[edit]Rewarding stimuli can drive learning in both the form of classical conditioning (Pavlovian conditioning) and operant conditioning (instrumental conditioning). In classical conditioning, a reward can act as an unconditioned stimulus that, when associated with the conditioned stimulus, causes the conditioned stimulus to elicit both musculoskeletal (in the form of simple approach and avoidance behaviors) and vegetative responses. In operant conditioning, a reward may act as a reinforcer in that it increases or supports actions that lead to itself.[1] Learned behaviors may or may not be sensitive to the value of the outcomes they lead to; behaviors that are sensitive to the contingency of an outcome on the performance of an action as well as the outcome value are goal-directed, while elicited actions that are insensitive to contingency or value are called habits.[55] This distinction is thought to reflect two forms of learning, model free and model based. Model free learning involves the simple caching and updating of values. In contrast, model based learning involves the storage and construction of an internal model of events that allows inference and flexible prediction. Although pavlovian conditioning is generally assumed to be model-free, the incentive salience assigned to a conditioned stimulus is flexible with regard to changes in internal motivational states.[56]

Distinct neural systems are responsible for learning associations between stimuli and outcomes, actions and outcomes, and stimuli and responses. Although classical conditioning is not limited to the reward system, the enhancement of instrumental performance by stimuli (i.e., Pavlovian-instrumental transfer) requires the nucleus accumbens. Habitual and goal directed instrumental learning are dependent upon the lateral striatum and the medial striatum, respectively.[55]

During instrumental learning, opposing changes in the ratio of AMPA to NMDA receptors and phosphorylated ERK occurs in the D1-type and D2-type MSNs that constitute the direct and indirect pathways, respectively.[57][58] These changes in synaptic plasticity and the accompanying learning is dependent upon activation of striatal D1 and NMDA receptors. The intracellular cascade activated by D1 receptors involves the recruitment of protein kinase A, and through resulting phosphorylation of DARPP-32, the inhibition of phosphatases that deactivate ERK. NMDA receptors activate ERK through a different but interrelated Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway. Alone NMDA mediated activation of ERK is self-limited, as NMDA activation also inhibits PKA mediated inhibition of ERK deactivating phosphatases. However, when D1 and NMDA cascades are co-activated, they work synergistically, and the resultant activation of ERK regulates synaptic plasticity in the form of spine restructuring, transport of AMPA receptors, regulation of CREB, and increasing cellular excitability via inhibiting Kv4.2.[59][60][61]

Disorders

[edit]Addiction

[edit]ΔFosB (DeltaFosB) – a gene transcription factor – overexpression in the D1-type medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens is the crucial common factor among virtually all forms of addiction (i.e., behavioral addictions and drug addictions) that induces addiction-related behavior and neural plasticity.[62][63][64][65] In particular, ΔFosB promotes self-administration, reward sensitization, and reward cross-sensitization effects among specific addictive drugs and behaviors.[62][63][64][66][67] Certain epigenetic modifications of histone protein tails (i.e., histone modifications) in specific regions of the brain are also known to play a crucial role in the molecular basis of addictions.[65][68][69][70]

Addictive drugs and behaviors are rewarding and reinforcing (i.e., are addictive) due to their effects on the dopamine reward pathway.[14][71]

The lateral hypothalamus and medial forebrain bundle has been the most-frequently-studied brain-stimulation reward site, particularly in studies of the effects of drugs on brain stimulation reward.[72] The neurotransmitter system that has been most-clearly identified with the habit-forming actions of drugs-of-abuse is the mesolimbic dopamine system, with its efferent targets in the nucleus accumbens and its local GABAergic afferents. The reward-relevant actions of amphetamine and cocaine are in the dopaminergic synapses of the nucleus accumbens and perhaps the medial prefrontal cortex. Rats also learn to lever-press for cocaine injections into the medial prefrontal cortex, which works by increasing dopamine turnover in the nucleus accumbens.[73][74] Nicotine infused directly into the nucleus accumbens also enhances local dopamine release, presumably by a presynaptic action on the dopaminergic terminals of this region. Nicotinic receptors localize to dopaminergic cell bodies and local nicotine injections increase dopaminergic cell firing that is critical for nicotinic reward.[75][76] Some additional habit-forming drugs are also likely to decrease the output of medium spiny neurons as a consequence, despite activating dopaminergic projections. For opiates, the lowest-threshold site for reward effects involves actions on GABAergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area, a secondary site of opiate-rewarding actions on medium spiny output neurons of the nucleus accumbens. Thus the following form the core of currently characterised drug-reward circuitry; GABAergic afferents to the mesolimbic dopamine neurons (primary substrate of opiate reward), the mesolimbic dopamine neurons themselves (primary substrate of psychomotor stimulant reward), and GABAergic efferents to the mesolimbic dopamine neurons (a secondary site of opiate reward).[72]

Motivation

[edit]Dysfunctional motivational salience appears in a number of psychiatric symptoms and disorders. Anhedonia, traditionally defined as a reduced capacity to feel pleasure, has been re-examined as reflecting blunted incentive salience, as most anhedonic populations exhibit intact "liking".[77][78] On the other end of the spectrum, heightened incentive salience that is narrowed for specific stimuli is characteristic of behavioral and drug addictions. In the case of fear or paranoia, dysfunction may lie in elevated aversive salience.[79] In modern literature, anhedonia is associated with the proposed two forms of pleasure, "anticipatory" and "consummatory".

Neuroimaging studies across diagnoses associated with anhedonia have reported reduced activity in the OFC and ventral striatum.[80] One meta analysis reported anhedonia was associated with reduced neural response to reward anticipation in the caudate nucleus, putamen, nucleus accumbens and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).[81]

Reward system development is particularly important in adolescents, as they can be prone to increased risk-taking behaviors, substance use disorders, and mood dysregulation.[82] Due to dopamine's role in reward processing, it can be linked to addictive behavior that may arise in adolescence. Risk taking behaviors and reward anticipation of monetary reward have been found to increase ventral striatum activity, a key region highlighted in the development of reward pathways.[82]

Mood disorders

[edit]Certain types of depression are associated with reduced motivation, as assessed by willingness to expend effort for reward. These abnormalities have been tentatively linked to reduced activity in areas of the striatum, and while dopaminergic abnormalities are hypothesized to play a role, most studies probing dopamine function in depression have reported inconsistent results.[83][84] Although postmortem and neuroimaging studies have found abnormalities in numerous regions of the reward system, few findings are consistently replicated. Some studies have reported reduced NAcc, hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) activity, as well as elevated basolateral amygdala and subgenual cingulate cortex (sgACC) activity during tasks related to reward or positive stimuli. These neuroimaging abnormalities are complemented by little post mortem research, but what little research has been done suggests reduced excitatory synapses in the mPFC.[85] Reduced activity in the mPFC during reward related tasks appears to be localized to more dorsal regions(i.e. the pregenual cingulate cortex), while the more ventral sgACC is hyperactive in depression.[86]

Attempts to investigate underlying neural circuitry in animal models has also yielded conflicting results. Two paradigms are commonly used to simulate depression, chronic social defeat (CSDS), and chronic mild stress (CMS), although many exist. CSDS produces reduced preference for sucrose, reduced social interactions, and increased immobility in the forced swim test. CMS similarly reduces sucrose preference, and behavioral despair as assessed by tail suspension and forced swim tests. Animals susceptible to CSDS exhibit increased phasic VTA firing, and inhibition of VTA-NAcc projections attenuates behavioral deficits induced by CSDS.[87] However, inhibition of VTA-mPFC projections exacerbates social withdrawal. On the other hand, CMS associated reductions in sucrose preference and immobility were attenuated and exacerbated by VTA excitation and inhibition, respectively.[88][89] Although these differences may be attributable to different stimulation protocols or poor translational paradigms, variable results may also lie in the heterogenous functionality of reward related regions.[90]

Optogenetic stimulation of the mPFC as a whole produces antidepressant effects. This effect appears localized to the rodent homologue of the pgACC (the prelimbic cortex), as stimulation of the rodent homologue of the sgACC (the infralimbic cortex) produces no behavioral effects. Furthermore, deep brain stimulation in the infralimbic cortex, which is thought to have an inhibitory effect, also produces an antidepressant effect. This finding is congruent with the observation that pharmacological inhibition of the infralimbic cortex attenuates depressive behaviors.[90]

Schizophrenia

[edit]Schizophrenia is associated with deficits in motivation, commonly grouped under other negative symptoms such as reduced spontaneous speech. The experience of "liking" is frequently reported to be intact,[91] both behaviorally and neurally, although results may be specific to certain stimuli, such as monetary rewards.[92] Furthermore, implicit learning and simple reward-related tasks are also intact in schizophrenia.[93] Rather, deficits in the reward system are apparent during reward-related tasks that are cognitively complex. These deficits are associated with both abnormal striatal and OFC activity, as well as abnormalities in regions associated with cognitive functions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC).[94]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

[edit]In those with ADHD, core aspects of the reward system are underactive, making it challenging to derive reward from regular activities. Those with the disorder experience a boost of motivation after a high-stimulation behaviour triggers a release of dopamine. In the aftermath of that boost and reward, the return to baseline levels results in an immediate drop in motivation.[95]

People with more ADHD-related behaviors show weaker brain responses to reward anticipation (not reward delivery), especially in the nucleus accumbens. While there is the initial boost of motivation and release of dopamine, as stated above, there is a higher risk of a noticeable drop in motivation.

Impairments of dopaminergic and serotonergic function are said to be key factors in ADHD.[96] These impairments can lead to executive dysfunction such as dysregulation of reward processing and motivational dysfunction, including anhedonia.[97]

History

[edit]

The first clue to the presence of a reward system in the brain came with an accidental discovery by James Olds and Peter Milner in 1954. They discovered that rats would perform behaviors such as pressing a bar, to administer a brief burst of electrical stimulation to specific sites in their brains. This phenomenon is called intracranial self-stimulation or brain stimulation reward. Typically, rats will press a lever hundreds or thousands of times per hour to obtain this brain stimulation, stopping only when they are exhausted. While trying to teach rats how to solve problems and run mazes, stimulation of certain regions of the brain where the stimulation was found seemed to give pleasure to the animals. They tried the same thing with humans and the results were similar. The explanation to why animals engage in a behavior that has no value to the survival of either themselves or their species is that the brain stimulation is activating the system underlying reward.[98]

In a fundamental discovery made in 1954, researchers James Olds and Peter Milner found that low-voltage electrical stimulation of certain regions of the brain of the rat acted as a reward in teaching the animals to run mazes and solve problems.[99][failed verification][100] It seemed that stimulation of those parts of the brain gave the animals pleasure,[99] and in later work humans reported pleasurable sensations from such stimulation.[citation needed] When rats were tested in Skinner boxes where they could stimulate the reward system by pressing a lever, the rats pressed for hours.[100] Research in the next two decades established that dopamine is one of the main chemicals aiding neural signaling in these regions, and dopamine was suggested to be the brain's "pleasure chemical".[101]

More recently, in 2018, Ivan De Araujo and colleagues used nutrients inside the gut to stimulate the reward system via the vagus nerve.[102]

Earlier history

[edit]Ivan Pavlov was a psychologist who used the reward system to study classical conditioning in the late 19th century. Pavlov used the reward system by rewarding dogs with food after they had heard a bell or another stimulus. Pavlov was rewarding the dogs so that the dogs associated food, the reward, with the bell, the stimulus.[103] Around the same time, Edward Thorndike used the reward system to study operant conditioning. He began by putting cats in a puzzle box and placing food outside of the box so that the cat wanted to escape. The cats worked to get out of the puzzle box to get to the food. Although the cats ate the food after they escaped the box, Thorndike learned that the cats attempted to escape the box without the reward of food. Thorndike used the rewards of food and freedom to stimulate the reward system of the cats. Thorndike used this to see how the cats learned to escape the box.[104]

Other species

[edit]Animals quickly learn to press a bar to obtain an injection of opiates directly into the midbrain tegmentum or the nucleus accumbens. The same animals do not work to obtain the opiates if the dopaminergic neurons of the mesolimbic pathway are inactivated. In this perspective, animals, like humans, engage in behaviors that increase dopamine release.

Kent Berridge, a researcher in affective neuroscience, found that sweet (liked ) and bitter (disliked ) tastes produced distinct orofacial expressions, and these expressions were similarly displayed by human newborns, orangutans, and rats. This was evidence that pleasure (specifically, liking) has objective features and was essentially the same across various animal species. Most neuroscience studies have shown that the more dopamine released by the reward, the more effective the reward is. This is called the hedonic impact, which can be changed by the effort for the reward and the reward itself. Berridge discovered that blocking dopamine systems did not seem to change the positive reaction to something sweet (as measured by facial expression). In other words, the hedonic impact did not change based on the amount of sugar. This discounted the conventional assumption that dopamine mediates pleasure. Even with more-intense dopamine alterations, the data seemed to remain constant.[105] However, a clinical study from January 2019 that assessed the effect of a dopamine precursor (levodopa), antagonist (risperidone), and a placebo on reward responses to music – including the degree of pleasure experienced during musical chills, as measured by changes in electrodermal activity as well as subjective ratings – found that the manipulation of dopamine neurotransmission bidirectionally regulates pleasure cognition (specifically, the hedonic impact of music) in human subjects.[106][107] This research demonstrated that increased dopamine neurotransmission acts as a sine qua non condition for pleasurable hedonic reactions to music in humans.[106][107]

Berridge developed the incentive salience hypothesis to address the wanting aspect of rewards. It explains the compulsive use of drugs by drug addicts even when the drug no longer produces euphoria, and the cravings experienced even after the individual has finished going through withdrawal. Some addicts respond to certain stimuli involving neural changes caused by drugs. This sensitization in the brain is similar to the effect of dopamine because wanting and liking reactions occur. Human and animal brains and behaviors experience similar changes regarding reward systems because these systems are so prominent.[105]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schultz W (2015). "Neuronal reward and decision signals: from theories to data". Physiological Reviews. 95 (3): 853–951. doi:10.1152/physrev.00023.2014. PMC 4491543. PMID 26109341.

Rewards in operant conditioning are positive reinforcers. ... Operant behavior gives a good definition for rewards. Anything that makes an individual come back for more is a positive reinforcer and therefore a reward. Although it provides a good definition, positive reinforcement is only one of several reward functions. ... Rewards are attractive. They are motivating and make us exert an effort. ... Rewards induce approach behavior, also called appetitive or preparatory behavior, sexual behavior, and consummatory behavior. ... Thus any stimulus, object, event, activity, or situation that has the potential to make us approach and consume it is by definition a reward. ... Rewarding stimuli, objects, events, situations, and activities consist of several major components. First, rewards have basic sensory components (visual, auditory, somatosensory, gustatory, and olfactory) ... Second, rewards are salient and thus elicit attention, which are manifested as orienting responses. The salience of rewards derives from three principal factors, namely, their physical intensity and impact (physical salience), their novelty and surprise (novelty/surprise salience), and their general motivational impact shared with punishers (motivational salience). A separate form not included in this scheme, incentive salience, primarily addresses dopamine function in addiction and refers only to approach behavior (as opposed to learning) ... Third, rewards have a value component that determines the positively motivating effects of rewards and is not contained in, nor explained by, the sensory and attentional components. This component reflects behavioral preferences and thus is subjective and only partially determined by physical parameters. Only this component constitutes what we understand as a reward. It mediates the specific behavioral reinforcing, approach generating, and emotional effects of rewards that are crucial for the organism's survival and reproduction, whereas all other components are only supportive of these functions. ... Rewards can also be intrinsic to behavior. They contrast with extrinsic rewards that provide motivation for behavior and constitute the essence of operant behavior in laboratory tests. Intrinsic rewards are activities that are pleasurable on their own and are undertaken for their own sake, without being the means for getting extrinsic rewards. ... Intrinsic rewards are genuine rewards in their own right, as they induce learning, approach, and pleasure, like perfectioning, playing, and enjoying the piano. Although they can serve to condition higher order rewards, they are not conditioned, higher order rewards, as attaining their reward properties does not require pairing with an unconditioned reward. ... These emotions are also called liking (for pleasure) and wanting (for desire) in addiction research and strongly support the learning and approach generating functions of reward.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Schultz, Wolfram (July 2015). "Neuronal Reward and Decision Signals: From Theories to Data". Physiological Reviews. 95 (3): 853–951. doi:10.1152/physrev.00023.2014. PMC 4491543. PMID 26109341.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Berridge KC, Kringelbach ML (May 2015). "Pleasure systems in the brain". Neuron. 86 (3): 646–664. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.018. PMC 4425246. PMID 25950633.

In the prefrontal cortex, recent evidence indicates that the [orbitofrontal cortex] OFC and insula cortex may each contain their own additional hot spots (D.C. Castro et al., Soc. Neurosci., abstract). In specific subregions of each area, either opioid-stimulating or orexin-stimulating microinjections appear to enhance the number of liking reactions elicited by sweetness, similar to the [nucleus accumbens] NAc and [ventral pallidum] VP hot spots. Successful confirmation of hedonic hot spots in the OFC or insula would be important and possibly relevant to the orbitofrontal mid-anterior site mentioned earlier that especially tracks the subjective pleasure of foods in humans (Georgiadis et al., 2012; Kringelbach, 2005; Kringelbach et al., 2003; Small et al., 2001; Veldhuizen et al., 2010). Finally, in the brainstem, a hindbrain site near the parabrachial nucleus of dorsal pons also appears able to contribute to hedonic gains of function (Söderpalm and Berridge, 2000). A brainstem mechanism for pleasure may seem more surprising than forebrain hot spots to anyone who views the brainstem as merely reflexive, but the pontine parabrachial nucleus contributes to taste, pain, and many visceral sensations from the body and has also been suggested to play an important role in motivation (Wu et al., 2012) and in human emotion (especially related to the somatic marker hypothesis) (Damasio, 2010).

- ^ Guo, Rong; Böhmer, Wendelin; Hebart, Martin; Chien, Samson; Sommer, Tobias; Obermayer, Klaus; Gläscher, Jan (14 December 2016). "Interaction of Instrumental and Goal-Directed Learning Modulates Prediction Error Representations in the Ventral Striatum". The Journal of Neuroscience. 36 (50). Society for Neuroscience: 12650–12660. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1677-16.2016. ISSN 0270-6474. PMC 6705659. PMID 27974615.

- ^ a b c d e Kolb, Bryan; Whishaw, Ian Q. (2001). An Introduction to Brain and Behavior (1st ed.). New York: Worth. pp. 438–441. ISBN 978-0-7167-5169-4.

- ^ Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (13 March 2019). "The Biology of Addiction". YouTube.

- ^ "Dopamine Involved In Aggression". Medical News Today. 15 January 2008. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Duarte, Isabel C.; Afonso, Sónia; Jorge, Helena; Cayolla, Ricardo; Ferreira, Carlos; Castelo-Branco, Miguel (1 May 2017). "Tribal love: the neural correlates of passionate engagement in football fans". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 12 (5): 718–728. doi:10.1093/scan/nsx003. PMC 5460049. PMID 28338882.

- ^ Lewis, Robert (April 2022). "The Brain's Reward System in Health and Disease". Advances in Experimental Medicine.

- ^ a b c Salamone, John D.; Correa, Mercè (November 2012). "The Mysterious Motivational Functions of Mesolimbic Dopamine". Neuron. 76 (3): 470–485. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.021. PMC 4450094. PMID 23141060.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yager LM, Garcia AF, Wunsch AM, Ferguson SM (August 2015). "The ins and outs of the striatum: Role in drug addiction". Neuroscience. 301: 529–541. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.033. PMC 4523218. PMID 26116518.

[The striatum] receives dopaminergic inputs from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the substantia nigra (SNr) and glutamatergic inputs from several areas, including the cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus (Swanson, 1982; Phillipson and Griffiths, 1985; Finch, 1996; Groenewegen et al., 1999; Britt et al., 2012). These glutamatergic inputs make contact on the heads of dendritic spines of the striatal GABAergic medium spiny projection neurons (MSNs) whereas dopaminergic inputs synapse onto the spine neck, allowing for an important and complex interaction between these two inputs in modulation of MSN activity ... It should also be noted that there is a small population of neurons in the [nucleus accumbens] NAc that coexpress both D1 and D2 receptors, though this is largely restricted to the NAc shell (Bertran- Gonzalez et al., 2008). ... Neurons in the NAc core and NAc shell subdivisions also differ functionally. The NAc core is involved in the processing of conditioned stimuli whereas the NAc shell is more important in the processing of unconditioned stimuli; Classically, these two striatal MSN populations are thought to have opposing effects on basal ganglia output. Activation of the dMSNs causes a net excitation of the thalamus resulting in a positive cortical feedback loop; thereby acting as a 'go' signal to initiate behavior. Activation of the iMSNs, however, causes a net inhibition of thalamic activity resulting in a negative cortical feedback loop and therefore serves as a 'brake' to inhibit behavior ... there is also mounting evidence that iMSNs play a role in motivation and addiction (Lobo and Nestler, 2011; Grueter et al., 2013). For example, optogenetic activation of NAc core and shell iMSNs suppressed the development of a cocaine CPP whereas selective ablation of NAc core and shell iMSNs ... enhanced the development and the persistence of an amphetamine CPP (Durieux et al., 2009; Lobo et al., 2010). These findings suggest that iMSNs can bidirectionally modulate drug reward. ... Together these data suggest that iMSNs normally act to restrain drug-taking behavior and recruitment of these neurons may in fact be protective against the development of compulsive drug use.

- ^ Taylor SB, Lewis CR, Olive MF (2013). "The neurocircuitry of illicit psychostimulant addiction: acute and chronic effects in humans". Subst Abuse Rehabil. 4: 29–43. doi:10.2147/SAR.S39684. PMC 3931688. PMID 24648786.

Regions of the basal ganglia, which include the dorsal and ventral striatum, internal and external segments of the globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, and dopaminergic cell bodies in the substantia nigra, are highly implicated not only in fine motor control but also in [prefrontal cortex] PFC function.43 Of these regions, the [nucleus accumbens] NAc (described above) and the [dorsal striatum] DS (described below) are most frequently examined with respect to addiction. Thus, only a brief description of the modulatory role of the basal ganglia in addiction-relevant circuits will be mentioned here. The overall output of the basal ganglia is predominantly via the thalamus, which then projects back to the PFC to form cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) loops. Three CSTC loops are proposed to modulate executive function, action selection, and behavioral inhibition. In the dorsolateral prefrontal circuit, the basal ganglia primarily modulate the identification and selection of goals, including rewards.44 The [orbitofrontal cortex] OFC circuit modulates decision-making and impulsivity, and the anterior cingulate circuit modulates the assessment of consequences.44 These circuits are modulated by dopaminergic inputs from the [ventral tegmental area] VTA to ultimately guide behaviors relevant to addiction, including the persistence and narrowing of the behavioral repertoire toward drug seeking, and continued drug use despite negative consequences.43–45

- ^ Grall-Bronnec M, Sauvaget A (2014). "The use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for modulating craving and addictive behaviours: a critical literature review of efficacy, technical and methodological considerations". Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 47: 592–613. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.013. PMID 25454360.

Studies have shown that cravings are underpinned by activation of the reward and motivation circuits (McBride et al., 2006, Wang et al., 2007, Wing et al., 2012, Goldman et al., 2013, Jansen et al., 2013 and Volkow et al., 2013). According to these authors, the main neural structures involved are: the nucleus accumbens, dorsal striatum, orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), amygdala, hippocampus and insula.

- ^ a b Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 365–366, 376. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

The neural substrates that underlie the perception of reward and the phenomenon of positive reinforcement are a set of interconnected forebrain structures called brain reward pathways; these include the nucleus accumbens (NAc; the major component of the ventral striatum), the basal forebrain (components of which have been termed the extended amygdala, as discussed later in this chapter), hippocampus, hypothalamus, and frontal regions of cerebral cortex. These structures receive rich dopaminergic innervation from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the midbrain. Addictive drugs are rewarding and reinforcing because they act in brain reward pathways to enhance either dopamine release or the effects of dopamine in the NAc or related structures, or because they produce effects similar to dopamine. ... A macrostructure postulated to integrate many of the functions of this circuit is described by some investigators as the extended amygdala. The extended amygdala is said to comprise several basal forebrain structures that share similar morphology, immunocytochemical features, and connectivity and that are well suited to mediating aspects of reward function; these include the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, the central medial amygdala, the shell of the NAc, and the sublenticular substantia innominata.

- ^ a b Richard JM, Castro DC, Difeliceantonio AG, Robinson MJ, Berridge KC (November 2013). "Mapping brain circuits of reward and motivation: in the footsteps of Ann Kelley". Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37 (9 Pt A): 1919–1931. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.12.008. PMC 3706488. PMID 23261404.

Figure 3: Neural circuits underlying motivated 'wanting' and hedonic 'liking'. - ^ Luo M, Zhou J, Liu Z (August 2015). "Reward processing by the dorsal raphe nucleus: 5-HT and beyond". Learn. Mem. 22 (9): 452–460. doi:10.1101/lm.037317.114. PMC 4561406. PMID 26286655.

- ^ Moulton EA, Elman I, Becerra LR, Goldstein RZ, Borsook D (May 2014). "The cerebellum and addiction: insights gained from neuroimaging research". Addiction Biology. 19 (3): 317–331. doi:10.1111/adb.12101. PMC 4031616. PMID 24851284.

- ^ Caligiore D, Pezzulo G, Baldassarre G, Bostan AC, Strick PL, Doya K, Helmich RC, Dirkx M, Houk J, Jörntell H, Lago-Rodriguez A, Galea JM, Miall RC, Popa T, Kishore A, Verschure PF, Zucca R, Herreros I (February 2017). "Consensus Paper: Towards a Systems-Level View of Cerebellar Function: the Interplay Between Cerebellum, Basal Ganglia, and Cortex". Cerebellum. 16 (1): 203–229. doi:10.1007/s12311-016-0763-3. PMC 5243918. PMID 26873754.

- ^ Ogawa, SK; Watabe-Uchida, M (2018). "Organization of dopamine and serotonin system: Anatomical and functional mapping of monosynaptic inputs using rabies virus". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 174: 9–22. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2017.05.001. PMID 28476484. S2CID 5089422.

- ^ Morales, M; Margolis, EB (February 2017). "Ventral tegmental area: cellular heterogeneity, connectivity and behaviour". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 18 (2): 73–85. doi:10.1038/nrn.2016.165. PMID 28053327. S2CID 10311562.

- ^ Lammel, S; Lim, BK; Malenka, RC (January 2014). "Reward and aversion in a heterogeneous midbrain dopamine system". Neuropharmacology. 76 Pt B: 351–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.019. PMC 3778102. PMID 23578393.

- ^ Nieh, EH; Kim, SY; Namburi, P; Tye, KM (20 May 2013). "Optogenetic dissection of neural circuits underlying emotional valence and motivated behaviors". Brain Research. 1511: 73–92. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.11.001. hdl:1721.1/92890. PMC 4099056. PMID 23142759.

- ^ Trantham-Davidson H, Neely LC, Lavin A, Seamans JK (2004). "Mechanisms underlying differential D1 versus D2 dopamine receptor regulation of inhibition in prefrontal cortex". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (47): 10652–10659. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3179-04.2004. PMC 5509068. PMID 15564581.

- ^ You ZB, Chen YQ, Wise RA (2001). "Dopamine and glutamate release in the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area of rat following lateral hypothalamic self-stimulation". Neuroscience. 107 (4): 629–639. doi:10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00379-7. PMID 11720786. S2CID 33615497.

- ^ Galván, Adriana (12 February 2010). "Adolescent development of the reward system". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 4: 6. doi:10.3389/neuro.09.006.2010. ISSN 1662-5161. PMC 2826184. PMID 20179786.

- ^ Galván, Adriana (12 February 2010). "Adolescent development of the reward system". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 4: 6. doi:10.3389/neuro.09.006.2010. ISSN 1662-5161. PMC 2826184. PMID 20179786.

- ^ a b Castro, DC; Cole, SL; Berridge, KC (2015). "Lateral hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens, and ventral pallidum roles in eating and hunger: interactions between homeostatic and reward circuitry". Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 9: 90. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2015.00090. PMC 4466441. PMID 26124708.

- ^ Carlezon WA, Jr; Thomas, MJ (2009). "Biological substrates of reward and aversion: a nucleus accumbens activity hypothesis". Neuropharmacology. 56 (Suppl 1): 122–32. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.075. PMC 2635333. PMID 18675281.

- ^ Wise RA, Rompre PP (1989). "Brain dopamine and reward". Annual Review of Psychology. 40: 191–225. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.001203. PMID 2648975.

- ^ Wise RA (October 2002). "Brain reward circuitry: insights from unsensed incentives". Neuron. 36 (2): 229–240. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00965-0. PMID 12383779. S2CID 16547037.

- ^ a b Kokane, S. S., & Perrotti, L. I. (2020). Sex Differences and the Role of Estradiol in Mesolimbic Reward Circuits and Vulnerability to Cocaine and Opiate Addiction. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 14.

- ^ Becker, J. B., & Chartoff, E. (2019). Sex differences in neural mechanisms mediating reward and addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology, 44(1), 166-183.

- ^ Stoof, J. C., & Kebabian, J. W. (1984). Two dopamine receptors: biochemistry, physiology and pharmacology. Life sciences, 35(23), 2281-2296.

- ^ Yin, H. H., Knowlton, B. J., & Balleine, B. W. (2005). Blockade of NMDA receptors in the dorsomedial striatum prevents action–outcome learning in instrumental conditioning. European Journal of Neuroscience, 22(2), 505-512.

- ^ a b c Koob, G. F., & Volkow, N. D. (2016). Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(8), 760-773.

- ^ Chau, Bolton (2018). "Dopamine and reward: a view from the prefrontal cortex". Behavioural Pharmacology. 29 (7): 569–583. doi:10.1097/FBP.0000000000000424. PMID 30188354.

- ^ Kutlu, M. G., & Gould, T. J. (2016). Effects of drugs of abuse on hippocampal plasticity and hippocampus-dependent learning and memory: contributions to development and maintenance of addiction. Learning & memory, 23(10), 515-533.

- ^ McGaugh, J. L. (July 2004). "The amygdala modulates the consolidation of memories of emotionally arousing experiences". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 27 (1): 1–28.

- ^ Koob G. F., Le Moal M. (2008). Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 59 29–53. 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] Koob G. F., Sanna P. P., Bloom F. E. (1998). Neuroscience of addiction. Neuron 21 467–476.

- ^ a b c Castro, DC; Berridge, KC (24 October 2017). "Opioid and orexin hedonic hotspots in rat orbitofrontal cortex and insula". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (43): E9125 – E9134. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E9125C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1705753114. PMC 5664503. PMID 29073109.

Here, we show that opioid or orexin stimulations in orbitofrontal cortex and insula causally enhance hedonic "liking" reactions to sweetness and find a third cortical site where the same neurochemical stimulations reduce positive hedonic impact.

- ^ Fischer AG, Ullsperger M (2017). "An Update on the Role of Serotonin and its Interplay with Dopamine for Reward". Front Hum Neurosci. 11 484. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2017.00484. PMC 5641585. PMID 29075184.

It has long been known from animal studies across different species that the raphe nuclei, the origin of most of the forebrain's serotonergic innervation, are among the most potent areas inducing self stimulation equivalent to stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle or the ventral tegmental area (VTA; Miliaressis et al., 1975; Van Der Kooy et al., 1978; Rompre and Miliaressis, 1985).

- ^ Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC (2012). "The Joyful Mind" (PDF). Scientific American. 307 (2): 44–45. Bibcode:2012SciAm.307b..40K. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0812-40. PMID 22844850. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

So it makes sense that the real pleasure centers in the brain – those directly responsible for generating pleasurable sensations – turn out to lie within some of the structures previously identified as part of the reward circuit. One of these so-called hedonic hotspots lies in a subregion of the nucleus accumbens called the medial shell. A second is found within the ventral pallidum, a deep-seated structure near the base of the forebrain that receives most of its signals from the nucleus accumbens. ...

On the other hand, intense euphoria is harder to come by than everyday pleasures. The reason may be that strong enhancement of pleasure – like the chemically induced pleasure bump we produced in lab animals – seems to require activation of the entire network at once. Defection of any single component dampens the high.

Whether the pleasure circuit – and in particular, the ventral pallidum – works the same way in humans is unclear. - ^ a b Berridge KC (April 2012). "From prediction error to incentive salience: mesolimbic computation of reward motivation". Eur. J. Neurosci. 35 (7): 1124–1143. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.07990.x. PMC 3325516. PMID 22487042.

Here I discuss how mesocorticolimbic mechanisms generate the motivation component of incentive salience. Incentive salience takes Pavlovian learning and memory as one input and as an equally important input takes neurobiological state factors (e.g. drug states, appetite states, satiety states) that can vary independently of learning. Neurobiological state changes can produce unlearned fluctuations or even reversals in the ability of a previously learned reward cue to trigger motivation. Such fluctuations in cue-triggered motivation can dramatically depart from all previously learned values about the associated reward outcome. ... Associative learning and prediction are important contributors to motivation for rewards. Learning gives incentive value to arbitrary cues such as a Pavlovian conditioned stimulus (CS) that is associated with a reward (unconditioned stimulus or UCS). Learned cues for reward are often potent triggers of desires. For example, learned cues can trigger normal appetites in everyone, and can sometimes trigger compulsive urges and relapse in addicts.

Cue-triggered 'wanting' for the UCS

A brief CS encounter (or brief UCS encounter) often primes a pulse of elevated motivation to obtain and consume more reward UCS. This is a signature feature of incentive salience.

Cue as attractive motivational magnets

When a Pavlovian CS+ is attributed with incentive salience it not only triggers 'wanting' for its UCS, but often the cue itself becomes highly attractive – even to an irrational degree. This cue attraction is another signature feature of incentive salience ... Two recognizable features of incentive salience are often visible that can be used in neuroscience experiments: (i) UCS-directed 'wanting' – CS-triggered pulses of intensified 'wanting' for the UCS reward; and (ii) CS-directed 'wanting' – motivated attraction to the Pavlovian cue, which makes the arbitrary CS stimulus into a motivational magnet. - ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 147–148, 367, 376. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

VTA DA neurons play a critical role in motivation, reward-related behavior (Chapter 15), attention, and multiple forms of memory. This organization of the DA system, wide projection from a limited number of cell bodies, permits coordinated responses to potent new rewards. Thus, acting in diverse terminal fields, dopamine confers motivational salience ("wanting") on the reward itself or associated cues (nucleus accumbens shell region), updates the value placed on different goals in light of this new experience (orbital prefrontal cortex), helps consolidate multiple forms of memory (amygdala and hippocampus), and encodes new motor programs that will facilitate obtaining this reward in the future (nucleus accumbens core region and dorsal striatum). In this example, dopamine modulates the processing of sensorimotor information in diverse neural circuits to maximize the ability of the organism to obtain future rewards. ...

The brain reward circuitry that is targeted by addictive drugs normally mediates the pleasure and strengthening of behaviors associated with natural reinforcers, such as food, water, and sexual contact. Dopamine neurons in the VTA are activated by food and water, and dopamine release in the NAc is stimulated by the presence of natural reinforcers, such as food, water, or a sexual partner. ...

The NAc and VTA are central components of the circuitry underlying reward and memory of reward. As previously mentioned, the activity of dopaminergic neurons in the VTA appears to be linked to reward prediction. The NAc is involved in learning associated with reinforcement and the modulation of motoric responses to stimuli that satisfy internal homeostatic needs. The shell of the NAc appears to be particularly important to initial drug actions within reward circuitry; addictive drugs appear to have a greater effect on dopamine release in the shell than in the core of the NAc. - ^ Berridge KC, Kringelbach ML (1 June 2013). "Neuroscience of affect: brain mechanisms of pleasure and displeasure". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 23 (3): 294–303. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2013.01.017. PMC 3644539. PMID 23375169.

For instance, mesolimbic dopamine, probably the most popular brain neurotransmitter candidate for pleasure two decades ago, turns out not to cause pleasure or liking at all. Rather dopamine more selectively mediates a motivational process of incentive salience, which is a mechanism for wanting rewards but not for liking them .... Rather opioid stimulation has the special capacity to enhance liking only if the stimulation occurs within an anatomical hotspot

- ^ Calipari, Erin S.; Bagot, Rosemary C.; Purushothaman, Immanuel; Davidson, Thomas J.; Yorgason, Jordan T.; Peña, Catherine J.; Walker, Deena M.; Pirpinias, Stephen T.; Guise, Kevin G.; Ramakrishnan, Charu; Deisseroth, Karl; Nestler, Eric J. (8 March 2016). "In vivo imaging identifies temporal signature of D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons in cocaine reward". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (10): 2726–2731. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.2726C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1521238113. PMC 4791010. PMID 26831103.

- ^ Baliki, M. N.; Mansour, A.; Baria, A. T.; Huang, L.; Berger, S. E.; Fields, H. L.; Apkarian, A. V. (9 October 2013). "Parceling Human Accumbens into Putative Core and Shell Dissociates Encoding of Values for Reward and Pain". Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (41): 16383–16393. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1731-13.2013. PMC 3792469. PMID 24107968.

- ^ Soares-Cunha, Carina; Coimbra, Barbara; Sousa, Nuno; Rodrigues, Ana J. (September 2016). "Reappraising striatal D1- and D2-neurons in reward and aversion". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 68: 370–386. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.021. hdl:1822/47044. PMID 27235078. S2CID 207092810.

- ^ Bamford, Nigel S.; Wightman, R. Mark; Sulzer, David (February 2018). "Dopamine's Effects on Corticostriatal Synapses during Reward-Based Behaviors". Neuron. 97 (3): 494–510. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.006. PMC 5808590. PMID 29420932.

- ^ Soares-Cunha, Carina; Coimbra, Barbara; David-Pereira, Ana; Borges, Sonia; Pinto, Luisa; Costa, Patricio; Sousa, Nuno; Rodrigues, Ana J. (September 2016). "Activation of D2 dopamine receptor-expressing neurons in the nucleus accumbens increases motivation". Nature Communications. 7 (1) 11829. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711829S. doi:10.1038/ncomms11829. PMC 4931006. PMID 27337658.

- ^ Soares-Cunha, Carina; Coimbra, Bárbara; Domingues, Ana Verónica; Vasconcelos, Nivaldo; Sousa, Nuno; Rodrigues, Ana João (March 2018). "Nucleus Accumbens Microcircuit Underlying D2-MSN-Driven Increase in Motivation". eNeuro. 5 (2): ENEURO.0386–18.2018. doi:10.1523/ENEURO.0386-18.2018. PMC 5957524. PMID 29780881.

- ^ Robinson, T; Berridge, K (December 1993). "The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction". Brain Research Reviews. 18 (3): 247–291. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. ISSN 0165-0173. PMID 8401595.

- ^ Koob G. F., Le Moal M. (2008). Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 59 29–53. 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] Koob G. F., Sanna P. P., Bloom F. E. (1998). Neuroscience of addiction. Neuron 21 467–476

- ^ Meyer, J. S., & Quenzer, L. F. (2013). Psychopharmacology: Drugs, the brain, and behavior. Sinauer Associates.

- ^ a b Yin, HH; Ostlund, SB; Balleine, BW (October 2008). "Reward-guided learning beyond dopamine in the nucleus accumbens: the integrative functions of cortico-basal ganglia networks". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 28 (8): 1437–48. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06422.x. PMC 2756656. PMID 18793321.

- ^ Dayan, P; Berridge, KC (June 2014). "Model-based and model-free Pavlovian reward learning: revaluation, revision, and revelation". Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 14 (2): 473–92. doi:10.3758/s13415-014-0277-8. PMC 4074442. PMID 24647659.

- ^ Balleine, BW; Morris, RW; Leung, BK (2 December 2015). "Thalamocortical integration of instrumental learning and performance and their disintegration in addiction". Brain Research. 1628 (Pt A): 104–16. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2014.12.023. hdl:1959.4/unsworks_46233. PMID 25514336. S2CID 11776683.

Importantly, we found evidence of increased activity in the direct pathway; both intracellular changes in the expression of the plasticity marker pERK and AMPA/NMDA ratios evoked by stimulating cortical afferents were increased in the D1-direct pathway neurons. In contrast, D2 neurons showed an opposing change in plasticity; stimulation of cortical afferents reduced AMPA/NMDA ratios on those neurons (Shan et al., 2014).

- ^ Nakanishi, S; Hikida, T; Yawata, S (12 December 2014). "Distinct dopaminergic control of the direct and indirect pathways in reward-based and avoidance learning behaviors". Neuroscience. 282: 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.04.026. PMID 24769227. S2CID 21652525.

- ^ Shiflett, MW; Balleine, BW (15 September 2011). "Molecular substrates of action control in cortico-striatal circuits". Progress in Neurobiology. 95 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.05.007. PMC 3175490. PMID 21704115.

- ^ Schultz, W (April 2013). "Updating dopamine reward signals". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 23 (2): 229–38. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2012.11.012. PMC 3866681. PMID 23267662.

- ^ Shiflett, MW; Balleine, BW (17 March 2011). "Contributions of ERK signaling in the striatum to instrumental learning and performance". Behavioural Brain Research. 218 (1): 240–7. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2010.12.010. PMC 3022085. PMID 21147168.

- ^ a b Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 15 (4): 431–443. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.4/enestler. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

- ^ a b Ruffle JK (November 2014). "Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?". Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 40 (6): 428–437. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840. PMID 25083822. S2CID 19157711.

The strong correlation between chronic drug exposure and ΔFosB provides novel opportunities for targeted therapies in addiction (118), and suggests methods to analyze their efficacy (119). Over the past two decades, research has progressed from identifying ΔFosB induction to investigating its subsequent action (38). It is likely that ΔFosB research will now progress into a new era – the use of ΔFosB as a biomarker. ...

Conclusions

ΔFosB is an essential transcription factor implicated in the molecular and behavioral pathways of addiction following repeated drug exposure. The formation of ΔFosB in multiple brain regions, and the molecular pathway leading to the formation of AP-1 complexes is well understood. The establishment of a functional purpose for ΔFosB has allowed further determination as to some of the key aspects of its molecular cascades, involving effectors such as GluR2 (87,88), Cdk5 (93) and NFkB (100). Moreover, many of these molecular changes identified are now directly linked to the structural, physiological and behavioral changes observed following chronic drug exposure (60,95,97,102). New frontiers of research investigating the molecular roles of ΔFosB have been opened by epigenetic studies, and recent advances have illustrated the role of ΔFosB acting on DNA and histones, truly as a molecular switch (34). As a consequence of our improved understanding of ΔFosB in addiction, it is possible to evaluate the addictive potential of current medications (119), as well as use it as a biomarker for assessing the efficacy of therapeutic interventions (121,122,124). Some of these proposed interventions have limitations (125) or are in their infancy (75). However, it is hoped that some of these preliminary findings may lead to innovative treatments, which are much needed in addiction. - ^ a b Olsen CM (December 2011). "Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions". Neuropharmacology. 61 (7): 1109–1122. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. PMC 3139704. PMID 21459101.

Functional neuroimaging studies in humans have shown that gambling (Breiter et al, 2001), shopping (Knutson et al, 2007), orgasm (Komisaruk et al, 2004), playing video games (Koepp et al, 1998; Hoeft et al, 2008) and the sight of appetizing food (Wang et al, 2004a) activate many of the same brain regions (i.e., the mesocorticolimbic system and extended amygdala) as drugs of abuse (Volkow et al, 2004). ... Cross-sensitization is also bidirectional, as a history of amphetamine administration facilitates sexual behavior and enhances the associated increase in NAc DA ... As described for food reward, sexual experience can also lead to activation of plasticity-related signaling cascades. The transcription factor delta FosB is increased in the NAc, PFC, dorsal striatum, and VTA following repeated sexual behavior (Wallace et al., 2008; Pitchers et al., 2010b). This natural increase in delta FosB or viral overexpression of delta FosB within the NAc modulates sexual performance, and NAc blockade of delta FosB attenuates this behavior (Hedges et al, 2009; Pitchers et al., 2010b). Further, viral overexpression of delta FosB enhances the conditioned place preference for an environment paired with sexual experience (Hedges et al., 2009). ... In some people, there is a transition from "normal" to compulsive engagement in natural rewards (such as food or sex), a condition that some have termed behavioral or non-drug addictions (Holden, 2001; Grant et al., 2006a). ... In humans, the role of dopamine signaling in incentive-sensitization processes has recently been highlighted by the observation of a dopamine dysregulation syndrome in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs. This syndrome is characterized by a medication-induced increase in (or compulsive) engagement in non-drug rewards such as gambling, shopping, or sex (Evans et al, 2006; Aiken, 2007; Lader, 2008)."

Table 1: Summary of plasticity observed following exposure to drug or natural reinforcers" - ^ a b Biliński P, Wojtyła A, Kapka-Skrzypczak L, Chwedorowicz R, Cyranka M, Studziński T (2012). "Epigenetic regulation in drug addiction". Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 19 (3): 491–496. PMID 23020045.

For these reasons, ΔFosB is considered a primary and causative transcription factor in creating new neural connections in the reward centre, prefrontal cortex, and other regions of the limbic system. This is reflected in the increased, stable and long-lasting level of sensitivity to cocaine and other drugs, and tendency to relapse even after long periods of abstinence. These newly constructed networks function very efficiently via new pathways as soon as drugs of abuse are further taken ... In this way, the induction of CDK5 gene expression occurs together with suppression of the G9A gene coding for dimethyltransferase acting on the histone H3. A feedback mechanism can be observed in the regulation of these 2 crucial factors that determine the adaptive epigenetic response to cocaine. This depends on ΔFosB inhibiting G9a gene expression, i.e. H3K9me2 synthesis which in turn inhibits transcription factors for ΔFosB. For this reason, the observed hyper-expression of G9a, which ensures high levels of the dimethylated form of histone H3, eliminates the neuronal structural and plasticity effects caused by cocaine by means of this feedback which blocks ΔFosB transcription

- ^ Pitchers KK, Vialou V, Nestler EJ, Laviolette SR, Lehman MN, Coolen LM (February 2013). "Natural and drug rewards act on common neural plasticity mechanisms with ΔFosB as a key mediator". The Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (8): 3434–3442. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4881-12.2013. PMC 3865508. PMID 23426671.

Drugs of abuse induce neuroplasticity in the natural reward pathway, specifically the nucleus accumbens (NAc), thereby causing development and expression of addictive behavior. ... Together, these findings demonstrate that drugs of abuse and natural reward behaviors act on common molecular and cellular mechanisms of plasticity that control vulnerability to drug addiction, and that this increased vulnerability is mediated by ΔFosB and its downstream transcriptional targets. ... Sexual behavior is highly rewarding (Tenk et al., 2009), and sexual experience causes sensitized drug-related behaviors, including cross-sensitization to amphetamine (Amph)-induced locomotor activity (Bradley and Meisel, 2001; Pitchers et al., 2010a) and enhanced Amph reward (Pitchers et al., 2010a). Moreover, sexual experience induces neural plasticity in the NAc similar to that induced by psychostimulant exposure, including increased dendritic spine density (Meisel and Mullins, 2006; Pitchers et al., 2010a), altered glutamate receptor trafficking, and decreased synaptic strength in prefrontal cortex-responding NAc shell neurons (Pitchers et al., 2012). Finally, periods of abstinence from sexual experience were found to be critical for enhanced Amph reward, NAc spinogenesis (Pitchers et al., 2010a), and glutamate receptor trafficking (Pitchers et al., 2012). These findings suggest that natural and drug reward experiences share common mechanisms of neural plasticity

- ^ Beloate LN, Weems PW, Casey GR, Webb IC, Coolen LM (February 2016). "Nucleus accumbens NMDA receptor activation regulates amphetamine cross-sensitization and deltaFosB expression following sexual experience in male rats". Neuropharmacology. 101: 154–164. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.023. PMID 26391065. S2CID 25317397.

- ^ Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (November 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 (11): 623–637. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB serves as one of the master control proteins governing this structural plasticity. ... ΔFosB also represses G9a expression, leading to reduced repressive histone methylation at the cdk5 gene. The net result is gene activation and increased CDK5 expression. ... In contrast, ΔFosB binds to the c-fos gene and recruits several co-repressors, including HDAC1 (histone deacetylase 1) and SIRT 1 (sirtuin 1). ... The net result is c-fos gene repression.

Figure 4: Epigenetic basis of drug regulation of gene expression - ^ Hitchcock LN, Lattal KM (2014). "Histone-mediated epigenetics in addiction". Epigenetics and Neuroplasticity—Evidence and Debate. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. Vol. 128. pp. 51–87. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800977-2.00003-6. ISBN 978-0-12-800977-2. PMC 5914502. PMID 25410541.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Walker DM, Nestler EJ (2018). "Neuroepigenetics and addiction". Neurogenetics, Part II. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 148. pp. 747–765. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-64076-5.00048-X. ISBN 978-0-444-64076-5. PMC 5868351. PMID 29478612.

- ^ Rang HP (2003). Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 596. ISBN 978-0-443-07145-4.

- ^ a b Roy A. Wise, Drug-activation of brain reward pathways, Drug and Alcohol Dependence 1998; 51 13–22.

- ^ Goeders N.E., Smith J.E. (1983). "Cortical dopaminergic involvement in cocaine reinforcement". Science. 221 (4612): 773–775. Bibcode:1983Sci...221..773G. doi:10.1126/science.6879176. PMID 6879176.

- ^ Goeders N.E., Smith J.E. (1993). "Intracranial cocaine self-administration into the medial prefrontal cortex increases dopamine turnover in the nucleus accumbens". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 265 (2): 592–600. doi:10.1016/S0022-3565(25)38192-9. PMID 8496810.

- ^ Clarke, Hommer D.W.; Pert A.; Skirboll L.R. (1985). "Electrophysiological actions of nicotine on substantia nigra single units". Br. J. Pharmacol. 85 (4): 827–835. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb11081.x. PMC 1916681. PMID 4041681.

- ^ Westfall, Thomas C.; Grant, Heather; Perry, Holly (January 1983). "Release of dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine from rat striatal slices following activation of nicotinic cholinergic receptors". General Pharmacology: The Vascular System. 14 (3): 321–325. doi:10.1016/0306-3623(83)90037-x. PMID 6135645.

- ^ Rømer Thomsen, K; Whybrow, PC; Kringelbach, ML (2015). "Reconceptualizing anhedonia: novel perspectives on balancing the pleasure networks in the human brain". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 9: 49. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00049. PMC 4356228. PMID 25814941.