Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Archosauriformes

View on Wikipedia

| Archosauriformes Temporal range: Latest Permian–Present,

| |

|---|---|

| |

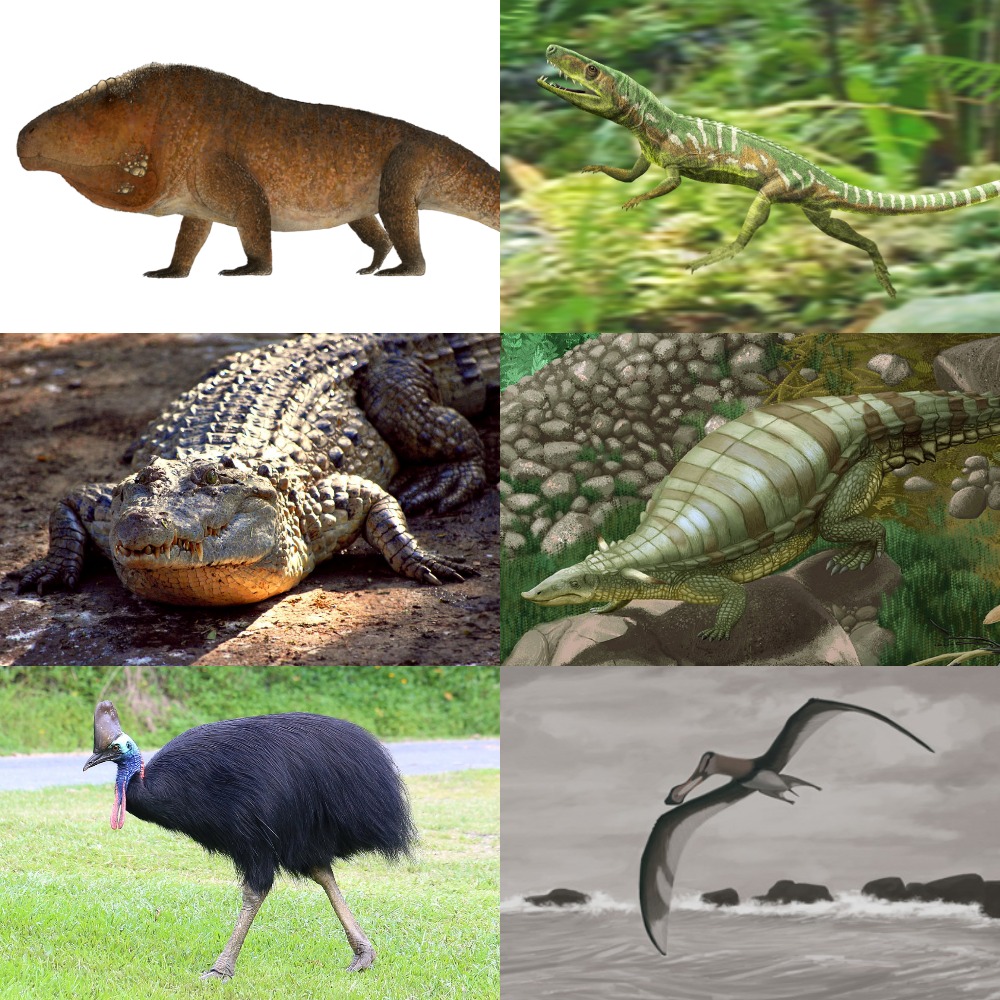

| Row 1 (basal archosauriforms): Erythrosuchus africanus, Euparkeria capensis; Row 2 (Pseudosuchia): Crocodylus mindorensis, Typothorax coccinarum; | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Crocopoda |

| Clade: | Archosauriformes Gauthier, 1986 |

| Subgroups[2] | |

| |

Archosauriformes (Greek for 'ruling lizards', and Latin for 'form') is a clade of diapsid reptiles encompassing archosaurs and some of their close relatives. It was defined by Jacques Gauthier (1994) as the clade stemming from the last common ancestor of Proterosuchidae and Archosauria.[3] Phil Senter (2005) defined it as the most exclusive clade containing Proterosuchus and Archosauria.[4] Gauthier as part of the Phylonyms (2020) defined the clade as the last common ancestor of Gallus, Alligator, and Proterosuchus, and all its descendants.[5] Archosauriforms are a branch of archosauromorphs which originated in the Late Permian (roughly 252 million years ago) and persist to the present day as the two surviving archosaur groups: crocodilians and birds.

Archosauriforms present several traits historically ascribed to the group Archosauria. These include serrated teeth set in deep sockets, a more active metabolism, and an antorbital fenestra (a hole in the skull in front of the eyes). Reptiles with these traits have also been termed "thecodonts" in older methods of classification. Thecodontia is a paraphyletic group, and its usage as a taxonomic category has been rejected under modern cladistic systems. The name Archosauriformes is intended as a monophyletic replacement compatible with modern taxonomy.

Evolutionary history

[edit]Early archosauriforms, informally termed "proterosuchians", were superficially crocodile-like animals with sprawling gaits, carnivorous habits, and long hooked snouts. Unlike the bulk of their therapsid contemporaries, archosauriforms survived the catastrophic end-Permian mass extinction. The Late Permian proterosuchid Archosaurus is similar in appearance to its Early Triassic relative, Proterosuchus. Within a few million years after the beginning of the Triassic, the archosauriformes had diversified past the "proterosuchian" grade. The next major archosauriform group was Erythrosuchidae, a family of apex predators with massive heads, the largest terrestrial carnivorous reptiles up to that time.

In 2016, Martin Ezcurra provided the name Eucrocopoda for the clade including all archosauriforms more crownward (closer to archosaurs) than erythrosuchids. He defined the clade all taxa more closely related to Euparkeria capensis, Proterochampa barrionuevoi, Doswellia kaltenbachi, Parasuchus hislopi, Passer domesticus (the house sparrow), or Crocodylus niloticus (the Nile crocodile) than to Proterosuchus fergusi or Erythrosuchus africanus. The name translates to "true crocodile feet", in reference to the possession of a crocodilian-style crurotarsal ankle.[2] Eucrocopodans include the families Euparkeriidae (small, agile reptiles),Proterochampsidae (narrow-snouted predators endemic to South America), and Doswelliidae (heavily armored Laurasian reptiles similar to proterochampsids), as well as various other strange reptiles such as Vancleavea and Asperoris.

The most successful archosauriforms, and the only members to survive into the Jurassic, were the archosaurs. Archosauria includes crocodilians, birds, and all descendants of their common ancestor. Extinct archosaurs include aetosaurs, rauisuchids (both members of the crocodilian branch), pterosaurs, and non-avian dinosaurs (both members of the avian branch).[6]

Metabolism

[edit]Vascular density and osteocyte density, shape and area have been used to estimate the bone growth rate of archosaurs, leading to the conclusion that this rate had a tendency to grow in ornithodirans and decrease in pseudosuchians.[7] The same method also supports the existence of high resting metabolical rates similar to those of living endotherms (mammals and birds) in the Prolacerta-Archosauriformes clade that were retained by most subgroups, though decreased in Proterosuchus, Phytosauria and Crocodilia.[8] Erythrosuchids and Euparkeria are basal archosauriforms showing signs of high growth rates and elevated metabolism, with Erythrosuchus possessing a rate similar of the fastest-growing dinosaurs. Sexual maturity in those Triassic taxa was probably reached quickly, providing advantage in a habitat with unpredictable variation from heavy rainfall to drought and high mortality. Vancleavea and Euparkeria, which show slower growth rates compared to Erythrosuchus, lived after the climatic stabilization. Early crown archosaurs possessed increased growth rates, which were retained by ornithodirans.[9] Ornithosuchians and poposaurs are stem-crocodilians that show high growth rates similar to those of basal archosauriforms.[10]

Developmental, physiological, anatomical and palaeontological lines of evidence indicate that crocodilians evolved from endothermic ancestors. Living crocodilians are ambush predators adapted to a semi-aquatic lifestyle that benefits from ectothermy due to the lower oxygen intake that allows longer diving time. The mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood in their circulatory system is apparently an innovation that benefits ectothermic life. Earlier archosaurs likely lacked those adaptations and instead had completely separated blood as birds and mammals do.[11][12] A similar process occurred in phytosaurs, which were also semi-aquatic.[13]

The similarities between pterosaur, ornithischian and coelurosaurian integument suggest a common origin of thermal insulation (feathers) in ornithodirans at least 250 million years ago.[14][15] Erythrosuchids living in high latitudes might have benefited from some sort of insulation.[13] If Longisquama was an archosauromorph, it could be associated with the origin of feathers.[16][13]

Relationships

[edit]Below is a cladogram from Nesbitt (2011):[17]

| Archosauriformes |

*Note: Phytosaurs were previously placed within Pseudosuchia, or crocodile-line archosaurs. |

Below is a cladogram from Sengupta et al. (2017),[18] based on an updated version of Ezcurra (2016)[2] that reexamined all historical members of the "Proterosuchia" (a polyphyletic historical group including proterosuchids and erythrosuchids). The placement of fragmentary taxa that had to be removed to increase tree resolution are indicated by dashed lines (in the most derived position that they can be confidently assigned to). Taxa that are nomina dubia are indicated by the note "dubium". Bold terminal taxa are collapsed.[2]

| Crocopoda |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sources

[edit]- Gauthier, J. A. (1986). "Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds". In Padian, K. (ed.). The Origin of Birds and the Evolution of Flight. Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences. Vol. 8. California Academy of Sciences. pp. 1–55. ISBN 978-0-940228-14-6.

- Gauthier, J. A.; Kluge, A. G.; Rowe, T. (June 1988). "Amniote phylogeny and the importance of fossils" (PDF). Cladistics. 4 (2). John Wiley & Sons: 105–209. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1988.tb00514.x. hdl:2027.42/73857. PMID 34949076. S2CID 83502693.

References

[edit]- ^ Sookias, R. B.; Sullivan, C.; Liu, J.; Butler, R. J. (2014). "Systematics of putative euparkeriids (Diapsida: Archosauriformes) from the Triassic of China". PeerJ. 2 e658. doi:10.7717/peerj.658. PMC 4250070. PMID 25469319.

- ^ a b c d Ezcurra, Martín D. (2016-04-28). "The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms". PeerJ. 4 e1778. doi:10.7717/peerj.1778. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4860341. PMID 27162705.

- ^ Gauthier J. A. (1994): The diversification of the amniotes. In: D. R. Prothero and R. M. Schoch (ed.) Major Features of Vertebrate Evolution: 129-159. Knoxville, Tennessee: The Paleontological Society.

- ^ Phil Senter (2005). "Phylogenetic taxonomy and the names of the major archosaurian (Reptilia) clades". PaleoBios. 25 (2): 1–7.

- ^ Gauthier, Jacques A. (2020). "Archosauriformes J. Gauthier 1986 [J. A. Gauthier], converted clade name". In De Queiroz, Kevin; Cantino, Philip; Gauthier, Jacques (eds.). Phylonyms: A Companion to the PhyloCode (1st ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. doi:10.1201/9780429446276. ISBN 978-0-429-44627-6. S2CID 242704712.

- ^ Anatomy, Phylogeny and Palaeobiology of Early Archosaurs and Their Kin

- ^ Cubo, Jorge; Roy, Nathalie Le; Martinez-Maza, Cayetana; Montes, Laetitia (2012). "Paleohistological estimation of bone growth rate in extinct archosaurs". Paleobiology. 38 (2): 335–349. Bibcode:2012Pbio...38..335C. doi:10.1666/08093.1. ISSN 0094-8373. S2CID 84303773.

- ^ Legendre, Lucas J.; Guénard, Guillaume; Botha-Brink, Jennifer; Cubo, Jorge (2016-11-01). "Palaeohistological evidence for ancestral high metabolic rate in archosaurs". Systematic Biology. 65 (6): 989–996. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syw033. ISSN 1063-5157. PMID 27073251.

- ^ Botha-Brink, Jennifer; Smith, Roger M. H. (2011-11-01). "Osteohistology of the Triassic archosauromorphs Prolacerta, Proterosuchus, Euparkeria, and Erythrosuchus from the Karoo Basin of South Africa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (6): 1238–1254. Bibcode:2011JVPal..31.1238B. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.621797. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 130744235.

- ^ de Ricqlès, Armand; Padian, Kevin; Knoll, Fabien; Horner, John R. (2008-04-01). "On the origin of high growth rates in archosaurs and their ancient relatives: Complementary histological studies on Triassic archosauriforms and the problem of a "phylogenetic signal" in bone histology". Annales de Paléontologie. 94 (2): 57–76. Bibcode:2008AnPal..94...57D. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2008.03.002. ISSN 0753-3969.

- ^ Seymour, Roger S.; Bennett-Stamper, Christina L.; Johnston, Sonya D.; Carrier, David R.; Grigg, Gordon C. (2004-11-01). "Evidence for endothermic ancestors of crocodiles at the stem of archosaur evolution" (PDF). Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 77 (6): 1051–1067. doi:10.1086/422766. hdl:2440/1933. ISSN 1522-2152. PMID 15674775. S2CID 10111065.

- ^ Summers, Adam P. (April 2005). "Warm-hearted crocs". Nature. 434 (7035): 833–834. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..833S. doi:10.1038/434833a. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 15829945. S2CID 4399224.

- ^ a b c "Dinosaur Renaissance". Scientific American. April 1975. Retrieved 2020-05-03.

- ^ Yang, Zixiao; Jiang, Baoyu; McNamara, Maria E.; Kearns, Stuart L.; Pittman, Michael; Kaye, Thomas G.; Orr, Patrick J.; Xu, Xing; Benton, Michael J. (January 2019). "Pterosaur integumentary structures with complex feather-like branching". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (1): 24–30. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0728-7. hdl:1983/1f7893a1-924d-4cb3-a4bf-c4b1592356e9. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 30568282. S2CID 56480710.

- ^ Benton, Michael J.; Dhouailly, Danielle; Jiang, Baoyu; McNamara, Maria (2019-09-01). "The early origin of feathers". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 34 (9): 856–869. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2019.04.018. hdl:10468/8068. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 31164250. S2CID 174811556.

- ^ Buchwitz, Michael; Voigt, Sebastian (2012-09-01). "The dorsal appendages of the Triassic reptile Longisquama insignis: reconsideration of a controversial integument type". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 86 (3): 313–331. Bibcode:2012PalZ...86..313B. doi:10.1007/s12542-012-0135-3. ISSN 1867-6812. S2CID 84633512.

- ^ Nesbitt, S.J. (2011). "The early evolution of archosaurs: relationships and the origin of major clades". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 1–292. doi:10.1206/352.1. hdl:2246/6112. S2CID 83493714.

- ^ Sengupta, S.; Ezcurra, M.D.; Bandyopadhyay, S. (2017). "A new horned and long-necked herbivorous stem-archosaur from the Middle Triassic of India". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 8366. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.8366S. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08658-8. PMC 5567049. PMID 28827583.