Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Audio feedback

View on Wikipedia

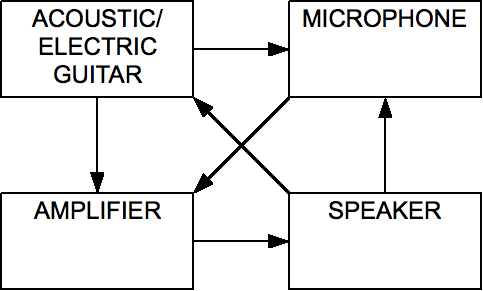

Audio feedback (also known as acoustic feedback, howlround in the UK, or simply as feedback) is a positive feedback situation that may occur when an acoustic path exists between an audio output (for example, a loudspeaker) and its audio input (for example, a microphone or guitar pickup). In this example, a signal received by the microphone is amplified and passed out of the loudspeaker. The sound from the loudspeaker can then be received by the microphone again, amplified further, and then passed out through the loudspeaker again. The frequency of the resulting howl is determined by resonance frequencies in the microphone, amplifier, and loudspeaker, the acoustics of the room, the directional pick-up and emission patterns of the microphone and loudspeaker, and the distance between them. The principles of audio feedback were first discovered by Danish scientist Søren Absalon Larsen, hence it is also known as the Larsen effect.

Feedback is almost always considered undesirable when it occurs with a singer's or public speaker's microphone at an event using a sound reinforcement system or PA system. Audio engineers typically use directional microphones with cardioid pickup patterns and various electronic devices, such as equalizers and, since the 1990s, automatic feedback suppressors, to prevent feedback, which detracts from the audience's enjoyment of the event and may damage equipment or hearing.

Since the 1960s, electric guitar players in rock music bands using loud guitar amplifiers, speaker cabinets and distortion effects have intentionally created guitar feedback to create different sounds including long sustained tones that cannot be produced using standard playing techniques. The sound of guitar feedback is considered to be a desirable musical effect in heavy metal music, hardcore punk and grunge. Jimi Hendrix was an innovator in the intentional use of guitar feedback in his guitar solos to create unique musical sounds.

History and theory

[edit]The conditions for feedback follow the Barkhausen stability criterion, namely that, with sufficiently high gain, a stable oscillation can (and usually will) occur in a feedback loop whose frequency is such that the phase delay is an integer multiple of 360 degrees and the gain at that frequency is equal to 1. If the small-signal gain is greater than 1 for some frequency, then the system will start to oscillate at that frequency because noise at that frequency will be amplified. Sound will be produced without anyone actually playing. The sound level will increase until the output starts clipping, reducing the loop gain to exactly unity. This is the principle upon which electronic oscillators are based; in that case, although the feedback loop is purely electronic, the principle is the same. If the gain is large but slightly less than 1, then ringing will be introduced, but only when at least some input sound is already being sent through the system.

Early academic work on acoustical feedback was done by Dr. C. Paul Boner.[2][3] Boner was responsible for establishing basic theories of acoustic feedback, room-ring modes, and room-sound system equalizing techniques. Boner reasoned that when feedback happened, it did so at one precise frequency. He also reasoned that it could be stopped by inserting a very narrow notch filter at that frequency in the loudspeaker's signal chain.[4] He worked with Gifford White, founder of White Instruments to hand craft notch filters for specific feedback frequencies in specific rooms.[5]

Distance

[edit]To maximize gain before feedback, the amount of sound energy that is fed back to the microphones must be reduced as much as is practical. As sound pressure falls off with 1/r with respect to the distance r in free space, or up to a distance known as reverberation distance in closed spaces (and the energy density with 1/r2), it is important to keep the microphones at a large enough distance from the speaker systems. As well, microphones should not be positioned in front of speakers, and individuals using mics should be asked to avoid pointing the microphone at speaker enclosures.

Directivity

[edit]Additionally, the loudspeakers and microphones should have non-uniform directivity and should stay out of the maximum sensitivity of each other, ideally in a direction of cancellation. Public address speakers often achieve directivity in the mid and treble region (and good efficiency) via horn systems. Sometimes the woofers have a cardioid characteristic.

Professional setups circumvent feedback by placing the main speakers away from the band or artist, and then having several smaller speakers known as monitors pointing back at each band member, but in the opposite direction to that in which the microphones are pointing taking advantage of microphones with a cardioid pickup pattern which are common in sound reinforcement applications. This configuration reduces the opportunities for feedback and allows independent control of the sound pressure levels for the audience and the performers.

Frequency response

[edit]Almost always, the natural frequency response of a sound reinforcement systems is not ideally flat as this leads to acoustical feedback at the frequency with the highest loop gain, which may be a resonance with much higher than the average gain over all frequencies. It is therefore helpful to apply some form of equalization to reduce the gain at this frequency.

Feedback can be reduced manually by ringing out a sound system prior to a performance. The sound engineer can increase the level of a microphone until feedback occurs. The engineer can then attenuate the relevant frequency on an equalizer, preventing feedback at that frequency but allowing sufficient volume at other frequencies. Many professional sound engineers can identify feedback frequencies by ear but others use a real-time analyzer to identify the ringing frequency.

To avoid feedback, an automatic feedback suppressor can be used. Some of these work by shifting the frequency slightly, with this upshift resulting in a chirp-sound instead of a howling sound of unaddressed feedback. Other devices use sharp notch filters to filter out offending frequencies. Adaptive algorithms are often used to automatically tune these notch filters.

Deliberate uses

[edit]

To intentionally create feedback, an electric guitar player needs a guitar amplifier with very high gain (amplification) or the guitar brought near the speaker. The guitarist then allows the strings to vibrate freely and brings the guitar close to the loudspeaker of the guitar amp. The use of distortion effects units adds additional gain and facilitates the creation of intentional feedback.

Early examples in popular music

[edit]A deliberate use of acoustic feedback was pioneered by blues and rock and roll guitarists such as Willie Johnson, Johnny Watson and Link Wray. According to AllMusic's Richie Unterberger, the very first use of feedback on a commercial rock record is the introduction of the song "I Feel Fine" by the Beatles, recorded in 1964.[6] Jay Hodgson agrees that this feedback created by John Lennon leaning a semi-acoustic guitar against an amplifier was the first chart-topper to showcase feedback distortion.[1]: 120–121 The Who's 1965 hits "Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere" and "My Generation" featured feedback manipulation by Pete Townshend, with an extended solo in the former and the shaking of his guitar in front of the amplifier to create a throbbing noise in the latter. Canned Heat's "Fried Hockey Boogie" also featured guitar feedback produced by Henry Vestine during his solo to create a highly amplified, distorted boogie style of feedback. In 1963, the teenage Brian May and his father custom-built his signature guitar Red Special, which was purposely designed to feed back.[7][8]

Feedback was used extensively after 1965 by the Monks,[9] Jefferson Airplane, the Velvet Underground and the Grateful Dead, who included in many of their live shows a segment named Feedback, a several-minute long feedback-driven improvisation. Feedback has since become a striking characteristic of rock music, as electric guitar players such as Jeff Beck, Pete Townshend, Dave Davies, Steve Marriott and Jimi Hendrix deliberately induced feedback by holding their guitars close to the amplifier's speaker. An example of feedback can be heard on Hendrix's performance of "Can You See Me?" at the Monterey Pop Festival. The entire guitar solo was created using amplifier feedback.[10] Jazz guitarist Gábor Szabó was one of the earliest jazz musicians to use controlled feedback in his music, which is prominent on his live album The Sorcerer (1967). Szabó's method included the use of a flat-top acoustic guitar with a magnetic pickup.[11] Lou Reed created his album Metal Machine Music (1975) entirely from loops of feedback played at various speeds.

Introductions, transitions, and fade-outs

[edit]In addition to "I Feel Fine", feedback was used on the introduction to songs including Jimi Hendrix's "Foxy Lady", the Beatles' "It's All Too Much", Hendrix's "Crosstown Traffic", David Bowie's "Little Wonder", the Strokes's "New York City Cops", Ben Folds Five's "Fair", Midnight Juggernauts's "Road to Recovery", Nirvana's "Radio Friendly Unit Shifter", the Jesus and Mary Chain's "Tumbledown" and "Catchfire", the Stone Roses's "Waterfall", Porno for Pyros's "Tahitian Moon", Tool's "Stinkfist", and the Cure's "Prayer For Rain".[1]: 121–122 Examples of feedback combined with a quick volume swell used as a transition include Weezer's "My Name Is Jonas" and "Say It Ain't So"; The Strokes' "Reptilia", "New York City Cops", and "Juicebox"; Dream Theater's "As I Am"; as well as numerous tracks by Meshuggah and Tool.[1]: 122–123

Cacophonous feedback fade-outs ending a song are most often used to generate rather than relieve tension, often cross-faded too after a thematic and musical release. Examples include Modwheelmood's remix of Nine Inch Nail's "The Great Destroyer"; and the Jesus and Mary Chain's "Teenage Lust", "Tumbledown", "Catchfire", "Sundown", and "Frequency".[1]: 123

Examples in modern classical music

[edit]Though closed circuit feedback was a prominent feature in many early experimental electronic music compositions, intentional acoustic feedback as sound material gained more prominence with compositions such as John Cage's Variations II (1961) performed by David Tudor and Robert Ashley's The Wolfman (1964). Steve Reich makes extensive use of audio feedback in his work Pendulum Music (1968) by swinging a series of microphones back and forth in front of their corresponding amplifiers.[12]: 88 Hugh Davies[12]: 84 and Alvin Lucier[12]: 91 both use feedback in their works. Roland Kayn based much of his compositional oeuvre, which he termed "cybernetic music," on audio systems incorporating feedback.[13][14] More recent examples can be found in the work of, for example, Lara Stanic,[12]: 163 Paul Craenen,[12]: 159 Anne Wellmer,[12]: 93 Adam Basanta,[15] Lesley Flanigan,[16] Ronald Boersen,[17] Erfan Abdi.[18] and Tyler Quinn [19]

Pitched feedback

[edit]Pitched melodies may be created entirely from feedback by changing the angle between a guitar and amplifier after establishing a feedback loop. Examples include Tool's "Jambi", Robert Fripp's guitar on David Bowie's "Heroes" (album version), and Jimi Hendrix's "Third Stone from the Sun" and his live performance of "Wild Thing" at the Monterey Pop Festival.[1]: 119

Regarding Fripp's work on "Heroes":

Fripp [stood] in the right place with his volume up at the right level and getting feedback...Fripp had a technique in those days where he measured the distance between the guitar and the speaker where each note would feed back. For instance, an 'A' would feed back maybe at about four feet from the speaker, whereas a 'G' would feed back maybe three and a half feet from it. He had a strip that they would place on the floor, and when he was playing the note 'F' sharp he would stand on the strip's 'F' sharp point and 'F' sharp would feed back better. He really worked this out to a fine science, and we were playing this at a terrific level in the studio, too.

— Tony Visconti[20][1]: 119

Contemporary uses

[edit]Audio feedback became a signature feature of many underground rock bands during the 1980s. American noise-rockers Sonic Youth melded the rock-feedback tradition with a compositional and classical approach (notably covering Reich's "Pendulum Music"), and guitarist/producer Steve Albini's group Big Black also worked controlled feedback into the makeup of their songs. With the alternative rock movement of the 1990s, feedback again saw a surge in popular usage by suddenly mainstream acts like Nirvana, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Rage Against the Machine and the Smashing Pumpkins. The use of the "no-input-mixer" method for sound generation by feeding a mixing console back into itself has been adopted in experimental electronic and noise music by practitioners such as Toshimaru Nakamura.[21]

Devices

[edit]

The principle of feedback is used in many guitar sustain devices. Examples include handheld devices like the EBow, built-in guitar pickups that increase the instrument's sonic sustain, and sonic transducers mounted on the head of a guitar. Intended closed-circuit feedback can also be created by an effects unit, such as a delay pedal or effect fed back into a mixing console. The feedback can be controlled by using the fader to determine a volume level. The Boss DF-2 Super Feedbacker and Distortion pedal is an electronic effect unit that helps electric guitarists create feedback effects.[22] The halldorophone is an electro-acoustic string instrument specifically made to work with string-based feedback.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Hodgson, Jay (2010). Understanding Records. ISBN 978-1-4411-5607-5.

- ^ C. Paul Boner, PhD.

- ^ In Memorium Charles Paul Boner

- ^ Behavior of Sound System Response Immediately Below Feedback, CP Boner, J. Audio Eng. Soc, 1966

- ^ Dennis Bohn (1990). "Operator Adjustable Equalizers: An Overview". Rane Corporation. Archived from the original on 2014-04-02.

- ^ Richie Unterberger. "'I Feel Fine' song review", AllMusic.com.

- ^ Hey, what's that sound: Homemade guitars The Guardian. Retrieved August 17, 2011

- ^ Brian May Interview The Music Biz (1992). Retrieved August 17, 2011

- ^ Shaw, Thomas Edward and Anita Klemke. Black Monk Time: A Book About the Monks. Reno: Carson Street Publishing, 1995.

- ^ "can you see me by jimi hendrix". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2013-02-26. Retrieved 2014-06-12.

- ^ "GABOR SZABO'S EQUIPMENT (GUITARS)". Doug Payne. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- ^ a b c d e f van Eck, Cathy (2017). Between Air and Electricity - Microphones and Loudspeakers as Musical Instruments. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-5013-2760-5.

- ^ "Cybernetic Music". kayn.nl. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Patteson, Thomas (2012). "The Time of Roland Kayn's Cybernetic Music" (PDF). Sonic Acts. 14: 47–67. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ van Eck, Cathy (6 July 2017). "Small Movements by Adam Basanta". Between Air and Electricity. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ van Eck, Cathy (16 May 2017). "Speaker Feedback Instruments by Lesley Flanigan". Between Air and Electricity. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ van Eck, Cathy (9 June 2017). "Sound in a Jar by Ronald Boersen". Between Air and Electricity. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ van Eck, Cathy (10 October 2017). "Points of Contact by Erfan Abdi". Between Air and Electricity. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Quinn, Tyler. "Afferent Manifestations via Reflective Pressure". Retrieved 24 February 2025.

- ^ Buskin, Richard (October 2004). "Classic Tracks: 'Heroes'", Sound On Sound.

- ^ "The Wire 300: Keith Moliné on the rise of Noise - the Wire".

- ^ "Boss DF-2 SUPER Feedbacker & Distortion". 2 March 2020. Retrieved 2021-10-13.

- ^ The halldorophone: The ongoing innovation of a cello-like drone instrument

External links

[edit]- Troxel, Dana (October 2005). "Understanding Acoustic Feedback & Suppressors". RaneNote. Rane.