Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Solomon ibn Gabirol

View on WikipediaSolomon ibn Gabirol or Solomon ben Judah (Hebrew: ר׳ שְׁלֹמֹה בֶּן יְהוּדָה אִבְּן גָּבִּירוֹל, romanized: Šəlomo ben Yəhūdā ʾībən Gābīrōl, pronounced [ʃ(e)loˈmo ben jehuˈda ʔibn ɡabiˈʁol]; Arabic: أبو أيوب سليمان بن يحيى بن جبيرول, romanized: ’Abū ’Ayyūb Sulaymān bin Yaḥyá bin Jabīrūl, pronounced [ˈʔæbuː ʔæjˈjuːb sʊlæjˈmæːn bɪn ˈjæħjæː bɪn dʒæbiːˈruːl]) was an 11th-century Jewish poet and philosopher in the neoplatonic tradition in Al-Andalus. He published over a hundred poems, as well as works of Hebrew Biblical exegesis, philosophy, ethics,[1]: xxvii and satire.[1]: xxv One source credits ibn Gabirol with creating a golem,[2] possibly female, for household chores.[3]

Key Information

In the 19th century, scholars discovered that medieval translators had Latinized ibn Gabirol's name to Avicebron or Avencebrol; his work on Jewish neoplatonic philosophy had become highly regarded in Islamic and Christian philosophical circles but attributed to only his Latinized name during the intervening years.[1]: xxxii [4] Ibn Gabirol is well known in the history of philosophy for the doctrine that all things, including souls and intellects, are composed of matter and form ("Universal Hylomorphism") and for his emphasis on divine will.[3]

Biography

[edit]

Little is known of Gabirol's life, and some sources give contradictory information.[1]: xvi Sources agree that he was born in Málaga, but are unclear whether in late 1021 or early 1022 CE.[1]: xvii The year of his death is a matter of dispute, with conflicting accounts having him dying either before age 30 or by age 48.[3]

Gabirol lived a life of material comfort, never having to work to sustain himself, but he lived a difficult and loveless life, suffering ill health, misfortunes, fickle friendships, and powerful enemies.[1]: xvii–xxvi From his teenage years, he suffered from some disease, possibly lupus vulgaris,[5] that would leave him embittered and in constant pain.[6] He indicates in his poems that he considered himself short and ugly.[6] Of his personality, Moses ibn Ezra wrote: "his irascible temperament dominated his intellect, nor could he rein the demon that was within himself. It came easily to him to lampoon the great, with salvo upon salvo of mockery and sarcasm."[5]: 17–18 He has been described summarily as "a social misfit."[7]: 12

Gabirol's writings indicate that his father was a prominent figure in Córdoba, but was forced to relocate to Málaga during a political crisis in 1013.[1]: xvii Gabirol's parents died while he was a child, leaving him an orphan with no siblings or close relatives.[1]: xviii He was befriended, supported and protected by a prominent political figure of the time, Yekutiel ibn Hassan al-Mutawakkil ibn Qabrun,[6] and moved to Zaragoza, then an important center of Jewish culture.[1]: xviii Gabirol's anti-social[3] temperament, occasionally boastful poetry, and sharp wit earned him powerful enemies, but as long as Jekuthiel lived, Gabirol remained safe from them[1]: xxiv and was able to freely immerse himself in study of the Talmud, grammar, geometry, astronomy, and philosophy.[8] However, when Gabirol was seventeen years old, his benefactor was assassinated as the result of a political conspiracy, and by 1045 Gabirol found himself compelled to leave Zaragoza.[1]: xxiv [8] He was then sponsored by no less than the grand vizier and top general to the kings of Granada, Samuel ibn Naghrillah (Shmuel HaNaggid).[1]: xxv Gabirol made ibn Naghrillah an object of praise in his poetry until an estrangement arose between them and ibn Naghrillah became the butt of Gabirol's bitterest irony. It seems Gabirol never married,[1]: xxvi and that he spent the remainder of his life wandering.[9]

Gabirol had become an accomplished poet and philosopher at an early age:

- By age 17, he had composed five of his known poems, one an azhara ("I am the master, and Song is my slave"[8]) enumerating all 613 commandments of Judaism.[1]: xix

- At age 17, he composed a 200-verse elegy for his friend Yekutiel[1]: xiv and four other notable elegies to mourn the death of Hai Gaon.[8]

- By age 19, he had composed a 400-verse alphabetical and acrostic poem teaching the rules of Hebrew grammar.[1]: xxv

- By age 23[8] or 25,[1]: xxv [6] he had composed, in Arabic, "Improvement of the Moral Qualities" (Arabic: كتاب إصلاح الأخلاق, translated into Hebrew by Judah ben Saul ibn Tibbon as Hebrew: תקון מדות הנפש)[8]

- At around age 25,[8] or not,[1]: xxv he may have composed his collection of proverbs Mivchar Pninim (lit. "Choice of Pearls"), although scholars are divided on his authorship.[3]

- At around age 28,[8] or not,[1]: xxv he composed his philosophical work Fons Vitæ.[1]: xxv

As mentioned above, the conflicting accounts of Gabirol's death have him dying either before age 30 or by age 48.[3] The opinion of earliest death, that he died before age 30, is believed to be based upon a misreading of medieval sources.[9] The remaining two opinions are that he died either in 1069 or 1070,[1]: xxvii or around 1058 in Valencia.[9][10] As to the circumstances of his death, one legend claims that he was trampled to death by an Arab horseman.[8] A second legend[11] relates that he was murdered by a Muslim poet who was jealous of Gabirol's poetic gifts, and who secretly buried him beneath the roots of a fig tree. The tree bore fruit in abundant quantity and of extraordinary sweetness. Its uniqueness excited attention and provoked an investigation. The resulting inspection of the tree uncovered Gabirol's remains, and led to the identification and execution of the murderer.

Historical identity

[edit]Though Gabirol's legacy was esteemed throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods, it was historically minimized by two errors of scholarship that mis-attributed his works.

False ascription as King Solomon

[edit]Gabirol seems to have often been called "the Málagan", after his place of birth, and would occasionally so refer to himself when encrypting his signature in his poems (e.g. in "שטר עלי בעדים", he embeds his signature as an acrostic in the form "אני שלמה הקטן ברבי יהודה גבירול מאלקי חזק" – meaning: "I am young Solomon, son of Rabi Yehuda, from Malaqa, Hazak"). While in Modern Hebrew the city is also called Málaga (Hebrew: מאלגה), that is in deference to its current Spanish pronunciation. In Gabirol's day, when it was ruled by Arabic speakers, it was called Mālaqa (Arabic: مالقة), as it is to this day by Arabic speakers. The 12th-century Arab philosopher Jabir ibn Aflah misinterpreted manuscript signatures of the form "שלמה ... יהודה ... אלמלאק" to mean "Solomon ... the Jew .. the king", and so ascribed to Solomon some seventeen philosophical essays of Gabirol. The 15th-century Jewish philosopher Yohanan Alemanno imported that error back into the Hebrew canon, and added another four works to the list of false ascriptions.[1]: xxx

Identification as Avicebron

[edit]In 1846, Solomon Munk discovered among the Hebrew manuscripts in the French National Library in Paris a work by Shem-Tov ibn Falaquera. Comparing it with a Latin work by Avicebron entitled Fons Vitæ, Munk proved them to both excerpt an Arabic original of which the Fons Vitæ was evidently the translation. Munk concluded that Avicebron or Avencebrol, who had for centuries been believed to be a Christian[6] or Arabic Muslim philosopher,[4] was instead identical with the Jewish Solomon ibn Gabirol.[1]: xxxi–xxxii [6][12] The centuries-long confusion was in part due to a content feature atypical in Jewish writings: Fons Vitæ exhibits an independence of Jewish religious dogma and does not cite Biblical verses or Rabbinic sources.[9]

The progression in the Latinization of Gabirol's name seems to have been ibn Gabirol, Ibngebirol, Avengebirol. Avengebrol, Avencebrol, Avicebrol, and finally Avicebron.[9] Some sources still refer to him as Avicembron, Avicenbrol, or Avencebrol.[3]

Philosophy

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Jewish philosophy |

|---|

|

Gabirol, in line 24 of his poem "כשרש עץ" (Like a Tree Root), claims to have written twenty philosophical works. Through scholarly deduction (see above), the works' titles are known, but the texts of only two have been found.[1]: xxxi

Gabirol made his mark on the history of philosophy under his alias as Avicebron, known as one of the first teachers of Neoplatonism in Europe and the author of Fons Vitæ.[9][13] As such, he is best known for the principle that all things, including soul and intellect, are composed of matter and form ("Universal Hylomorphism"), and for his emphasis on divine will.[3]

His role has often been likened to that of Philo: both were overlooked by their fellow Jews yet wielded significant influence over gentiles—Philo impacting early Christianity and ibn Gabirol shaping medieval Christian scholasticism. Additionally, both acted as cultural intermediaries—Philo bridging Hellenistic philosophy with the Oriental world, and ibn Gabirol connecting Greco-Arabic philosophy with the West.[9]

Fons Vitæ

[edit]Fons Vitæ, originally written in Arabic under the title Yanbu' al-Hayat (Arabic: ينبوع الحياة) and later translated into Hebrew by Ibn Tibbon as Hebrew: מקור חיים, pronounced [mɛ.ˈkor xay.ˈyim], lit. "Source of Life" (cf. Psalms 36:10) is a Neo-Platonic philosophical dialogue between master and disciple on the nature of Creation and how understanding what we are (our nature) can help us know how to live (our purpose).[3] "His goal is to understand the nature of being and human being so that he might better understand and better inspire the pursuit of knowledge and the doing of good deeds."[3] The work stands out in the history of philosophy for introducing the doctrine that all things, including soul and intellect, are composed of matter and form, and for its emphasis on divine will.[3]

- Student: What is the purpose of man?

- Teacher: The inclination of his soul to the higher world in order that everyone might return to his like.

- (Fons Vitæ 1.2, p. 4, lines 23–25)[3]

In the closing sentences of the Fons Vitæ (5.43, p. 338, line 21), ibn Gabirol further describes this state of "return" as a liberation from death and a cleaving to the source of life.[3]

The work was originally composed in Arabic, of which no copies are extant. It was preserved for the ages by a translation into Latin in the year 1150 by Abraham ibn Daud and Dominicus Gundissalinus, who was the first official director of the Toledo School of Translators, a scholastic philosopher, and the archdeacon of Segovia, Spain.[1]: xxx In the 13th century, Shem Tov ibn Falaquera wrote a summary of Fons Vitæ in Hebrew,[3] and only in 1926 was the complete Latin text translated into Hebrew.[8]

Fons Vitæ consists of five sections:[9]

- matter and form in general and their relation in physical substances (Latin: substantiæ corporeæ sive compositæ);

- the substance which underlies the corporeality of the world (Latin: de substantia quæ sustinet corporeitatem mundi);

- proofs of the existence of intermediaries between God and the physical world (Latin: substantiæ simplices, lit. "intelligibiles");

- proofs that these "intelligibiles" are likewise constituted of matter and form;

- universal matter and universal form.

Fons Vitæ posits that the basis of existence and the source of life in every created thing is a combination of "matter" (Latin: materia universalis) and "form". The doctrine of matter and form informed the work's subtitle: "De Materia et Forma."[14] Its chief doctrines are:[9]

- Everything that exists may be reduced to three categories:

- God

- Matter and form (i.e., Creation)

- Will (an intermediary)

- All created beings are constituted of form and matter.

- This holds true for both the physical world (Latin: substantiis corporeis sive compositis) and the spiritual world (Latin: substantiis spiritualibus sive simplicibus), which latter are the connecting link between the first substance (i.e., the Godhead, Latin: essentia prima) and the physical world (Latin: substantia, quæ sustinet novem prædicamenta, lit. "substance divided into nine categories").

- Matter and form are always and everywhere in the relation of "sustinens" and "sustentatum", "propriatum" and "proprietas": substratum and property or attribute.

Influence within Judaism

[edit]Though Gabirol as a philosopher was ignored by the Jewish community, Gabirol as a poet was not, and through his poetry, he introduced his philosophical ideas.[4] His best-known poem, Keter Malkut ("Royal Crown"), is a philosophical treatise in poetical form, the "double" of the Fons Vitæ. For example, the eighty-third line of the poem points to one of the teachings of the Fons Vitæ; namely, that all the attributes predicated of God exist apart in thought alone and not in reality.[9]

Moses ibn Ezra is the first to mention Gabirol as a philosopher, praising his intellectual achievements, and quoting several passages from the Fons Vitæ in his own work, Aruggat ha-Bosem.[9] Abraham ibn Ezra, who cites Gabirol's philosophico-allegorical Bible interpretation, borrows from the Fons Vitæ both in his prose and in his poetry without giving due credit.[9]

The 12th-century philosopher Joseph ibn Tzaddik borrows extensively from the "Fons Vitæ" in his work Microcosmos.[9]

Another 12th-century philosopher, Abraham ibn Daud of Toledo, was the first to take exception to Gabirol's teachings. In Sefer ha-Kabbalah, he praises Gabirol as a poet. But to counteract the influence of ibn Gabirol the philosopher, he wrote an Arabic book, translated into Hebrew under the title Emunah Ramah, in which he reproaches Gabirol for having philosophized without any regard to the requirements of the Jewish religious position and bitterly accuses him of mistaking a number of poor reasons for one good one.[9] He criticizes Gabirol for being repetitive, wrong-headed and unconvincing.[3]

Occasional traces of ibn Gabriol's thought are found in some of the Kabbalistic literature of the 13th century. Later references to ibn Gabirol, such as those of Elijah Habillo, Isaac Abarbanel, Judah Abarbanel, Moses Almosnino, and Joseph Solomon Delmedigo, are based on an acquaintance with the scholastic philosophy, especially the works of Aquinas.[9]

The 13th-century Jewish philosopher Berechiah ha-Nakdan drew upon Gabirol's works in his encyclopedic philosophical text Sefer Haḥibbur (Hebrew: ספר החיבור, pronounced [ˈsefeʁ haχiˈbuʁ], lit. "The Book of Compilation").

Influence on Scholasticism

[edit]For over six centuries, the Christian world regarded Fons Vitæ as the work of a Christian philosopher[6] or Arabic Muslim philosopher,[1]: xxxi–xxxii [4][6][12] and it became a cornerstone and bone of contention in many theologically charged debates between Franciscans and Dominicans.[3][9] The Aristotelian Dominicans led by St. Albertus Magnus and St. Thomas Aquinas opposed the teachings of Fons Vitæ; the Platonist Franciscans led by Duns Scotus supported its teachings, and led to its acceptance in Christian philosophy, influencing later philosophers such as the 16th-century Dominican friar Giordano Bruno.[9] Other early supporters of Gabirol's philosophy include the following:[9]

- Dominicus Gundissalinus, who translated the Fons Vitæ into Latin and incorporated its ideas into his own teaching.

- William of Auvergne, who refers to the work of Gabirol under the title Fons Sapientiæ. He speaks of Gabirol as a Christian and praises him as "unicus omnium philosophantium nobilissimus."

- Alexander of Hales and his disciple Bonaventura, who accept the teaching of Gabirol that spiritual substances consist of matter and form.

- William of Lamarre

The main points at issue between Gabirol and Aquinas were as follows:[9]

- the universality of matter, Aquinas holding that spiritual substances are immaterial;

- the plurality of forms in a physical entity, which Aquinas denied;

- the power of activity of physical beings, which Gabirol affirmed. Aquinas held that Gabirol made the mistake of transferring the theoretical combination of genus and species to real existence, and that he thus came to the erroneous conclusion that, in reality, all things are constituted of matter and form as genus and species, respectively.

Ex nihilo

[edit]Gabirol denied the idea of "creation ex nihilo" because he felt that that idea would make God "subject to the [laws of existence]".[15]

Ethics

[edit]The Improvement of the Moral Qualities

[edit]| Sight | Hearing |

Pride |

Love |

| Smell | Taste |

Wrath |

Joy (cheerfulness) |

| Touch | |

Liberality | |

The Improvement of the Moral Qualities, originally written in Arabic under the title Islah al-Khlaq (Arabic: إصلاح الأخلاق), and later translated by Ibn Tibbon as (Hebrew: "תקון מדות הנפש", pronounced [ti.'kun mi.ˈdot ha.ˈne.feʃ]) is an ethical treatise that has been called by Munk "a popular manual of morals."[9]: Ethical Treatise It was composed by Gabirol at Zaragoza in 1045, at the request of some friends who wished to possess a book treating of the qualities of man and the methods of effecting their improvement.[9]

The innovations in the work are that it presents the principles of ethics independently of religious dogma and that it proposes that the five physical senses are emblems and instruments of virtue and vice, but not their agents; thus, a person's inclination to vice is subject to a person's will to change.[9] Gabirol presents a tabular diagram of the relationship of twenty qualities to the five senses, reconstructed at right,[9] and urges his readers to train the qualities of their souls unto good through self-understanding and habituation. He regards man's ability to do so as an example of divine benevolence.[9]

While this work of Gabirol is not widely studied in Judaism, it has many points in common with Bahya ibn Paquda's very popular[citation needed] work Chovot HaLevavot,[9] written in 1040, also in Zaragoza.

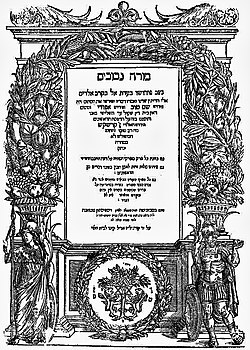

Mivchar HaPeninim

[edit]

Mukhtar al-Jawahir (Arabic: مختار الجواهر), Mivchar HaPeninim (Hebrew: מבחר הפנינים. lit. "The Choice of Pearls"), an ethics work of sixty-four chapters, has been attributed to Gabirol since the 19th century, but this is doubtful.[17] It was originally published, along with a short commentary, in Soncino, Italy, in 1484, and has since been re-worked and re-published in many forms and abridged editions (e.g. Joseph Ḳimcḥi versified the work under the title "Shekel ha-Kodesh").[9]

The work is a collection of maxims, proverbs, and moral reflections, many of them of Arabic origin, and bears a strong similarity to the Florilegium of Hunayn ibn Ishaq and other Arabic and Hebrew collections of ethics sayings, which were highly prized by both Arabs and Jews.[9]

Poetry

[edit]Gabirol wrote both sacred and secular poems, in Hebrew, and was recognized even by his critics (e.g. Moses ibn Ezra and Yehuda Alharizi) as the greatest poet of his age.[1]: xxii

Gabirol's lasting poetic legacy, however, was his sacred works. Today, "his religious lyrics are considered by many to be the most powerful of their kind in the medieval Hebrew tradition, and his long cosmological masterpiece, Keter Malchut, is acknowledged today as one of the greatest poems in all of Hebrew literature."[6] His verses are distinctive for tackling complex metaphysical concepts, expressing scathing satire, and declaring his religious devotion unabashedly.[6]

Gabirol wrote with a pure Biblical Hebrew diction that would become the signature style of the Spanish school of Hebrew poets,[9] and he popularized in Hebrew poetry the strict Arabic meter introduced by Dunash ben Labrat. Abraham ibn Ezra[18] calls Gabirol, not ben Labrat, "the writer of metric songs," and in Sefer Zaḥot uses Gabirol's poems to illustrate various poetic meters.[9]

He wrote also more than one hundred piyyuṭim and selichot for the Sabbath, festivals, and fast-days, most of which have been included in the Holy Day prayer books of Sephardim, Ashkenazim, and even Karaites[9] Some of his most famous in liturgical use include the following:[8]

- Azharot

- Keter Malchuth (lit. Royal Crown), for recitation on Yom Kippur[3]

- various dirges (kinnot) mourning the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and the plight of Israel

Gabirol's most famous poem is Keter Malchut (lit. Royal Crown), which, in 900 lines, describes the cosmos as testifying to its own creation by God, based upon the then current (11th-century) scientific understanding of the cosmos.

Some popular examples that are often sung outside of the liturgy include: Shalom L'ben Dodi,[19] Shachar Abakeshcha.[citation needed][example needed]

Gabirol's poetry has been set to music by the modern composer Aaron Jay Kernis, in an album titled "Symphony of Meditations."[20]

In 2007 Gabirol's poetry has been set to music by the Israeli rock guitarist Berry Sakharof and the Israeli modern composer Rea Mochiach, in a piece titled "Red Lips" ("Adumey Ha-Sefatot" "אֲדֻמֵּי הַשְּׂפָתוֹת") [21]

Editions and translations

[edit]- אבן גבירול שלמה ב"ר יהודה הספרדי (1928–1929). ביאליק, ח. נ.; רבניצקי, ח. (eds.). שירי שלמה בן יהודה אבן Shire Shelomoh ben Yehudah ibn Gabirol: meḳubatsim ʼal-pi sefarim ṿe-kitve-yad. תל אביבגבירול.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), vol. 1, vol. 2, vol. 3, vol. 4, vol. 5, vol. 6. - Shelomoh Ibn Gabirol, shirei ha-ḥol, ed. by H. Brody and J. Schirmann (Jerusalem 1975)

- Shirei ha-ḥol le-rabbi Shelomoh Ibn Gabirol, ed. by Dov Jarden (Jerusalem, 1975)

- Selomó Ibn Gabirol, Selección de perlas = Mibḥar ha-penînîm: (máximas morales, sentencias e historietas), trans. by David Gonzalo Maeso (Barcelona: Ameller, 1977)

- Selomo Ibn Gabirol, Poesía secular, trans. by Elena Romero ([Madrid]: Ediciones Alfaguara, 1978)

- Šelomoh Ibn Gabirol, Poemas seculares, ed. by M. J. Cano (Granada: Universidad de Granada; [Salamanca]: Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, 1987)

- Ibn Gabirol, Poesía religiosa, ed. by María José Cano (Granada: Universidad de Granada, 1992)

- Selected poems of Solomon Ibn Gabirol, trans. by Peter Cole (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Davidson, Israel (1924). Selected Religious Poems of Solomon ibn Gabirol. Schiff Library of Jewish Classics. Translated by Zangwill, Israel. Philadelphia: JPS. p. 247. ISBN 0-8276-0060-7. LCCN 73-2210.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Bokser, Ben Zion (2006). From the World of the Cabbalah. Kessinger. p. 57. ISBN 9781428620858.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Pessin, Sarah (April 18, 2014). "Solomon Ibn Gabirol [Avicebron]". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2014 ed.). Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 152.

- ^ a b Raphael, Loewe (1989). Ibn Gabirol. London: Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Shelomo Ibn Gabirol (1021/22 – c. 1057/58)". pen.org. Pen America. 16 February 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Scheindlin, Raymond P. (1986). Wine, Women, & Death: Medieval Hebrew Poems on the Good Life. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. p. 204. ISBN 978-0195129878.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Solomon Ibn Gabirol". chabad.org. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "IBN GABIROL, SOLOMON BEN JUDAH (ABU AYYUB SULAIMAN IBN YAḤYA IBN JABIRUL), known also as Avicebron". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "IBN GABIROL, SOLOMON BEN JUDAH (ABU AYYUB SULAIMAN IBN YAḤYA IBN JABIRUL), known also as Avicebron". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ^ Sirat, Colette (1985). A History of Jewish Philosophy in the Middle Ages. cambridge: Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ ibn Yahya, Gedaliah (1587). Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah (in Hebrew). Venice.

- ^ a b Munk, Solomon (1846). "??". Literaturblatt des Orients. 46. Also, see Munk, Salomon (1859). Mélanges de philosophie juive et arabe (in French). Paris: A. Franck.

- ^ Oesterley, W. O. E.; Box, G. H. (1920). A Short Survey of the Literature of Rabbinical and Mediæval Judaism. New York: Burt Franklin.

- ^ The manuscript in the Mazarine Library is entitled "De Materia Universali"

- ^ Armstrong, Karen (1996). A History of God: The 4000-year Quest of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-679-42600-4.

- ^ Ibn Gabirol, Shelomo (1899). Mivchar HaPninim (in Hebrew). London. p. 208. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Ibn Gabirol, Solomon ben Judah". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ Commentary on Gen. 3: 1

- ^ "ArtScroll.com - The ArtScroll Sephardic Siddur - Schottenstein Edition". www.artscroll.com. Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ "Kernis Takes On Ibn Gabirol in 'Meditations'". PBS. July 2009.

- ^ "Berry Sakharof discography". Discogs.

Further reading

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 221.

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Ibn Gabirol, Solomon ben Judah". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Endnotes:

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Ibn Gabirol, Solomon ben Judah". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Endnotes:

- H. Adler, Ibn Gabirol and His Influence upon Scholastic Philosophy, London, 1865;

- Ascher, A Choice of Pearls, London, 1859;

- Bacher, Bibelexegese der Jüdischen, Religionsphilosophen des Mittelalters, pp. 45–55, Budapest, 1892;

- Bäumker, Avencebrolis Fons Vitæ, Muuünster, 1895;

- Beer, Philosaphie und Philosophische Schriftsteller der Juden, Leipsic, 1852;

- Bloch, Die Jüdische Religionsphilosophic, in Winter and Wünsche, Die Jüdische Litteratur, ii. 699–793, 723–729;

- Dukes, Ehrensäulen, und Denksteine, pp. 9–25, Vienna, 1837;

- idem. Salomo ben Gabirol aus Malaga und die Ethischen Werke Desselben, Hanover, 1860;

- Eisler, Vorlesungen über die Jüdischen Philosophen des Mittelalters, i. 57–81, Vienna, 1876;

- Geiger, Salomo Gabirol und Seine Dichtungen, Leipsic, 1867;

- Graetz, History of the Jews. iii. 9;

- Guttman, Die Philosophie des Salomon ibn Gabirol, Göttingen, 1889;

- Guttmann, Das Verhältniss des Thomas von Aquino zum Judenthum und zur Jödischen Litteratur, especially ii. 16–30, Götingen, 1891;

- Horovitz, Die Psychologie Ibn Gabirols, Breslau, 1900;

- Joël, Ibn Gebirol's Bedeutung für die Gesch. der Philosophie, Beiträge zur Gesch. der philosophie, i., Breslau, 1876;

- Kümpf, Nichtandalusische Poesie Andalusischer Dichter, pp. 167–191, Prague, 1858;

- Karpeles, Gesch. der Jüdischen Litteratur, i. 465–483, Berlin, 1886;

- Kaufmann, Studien über Salomon ibn Gabirol, Budapest, 1899;

- Kaufmann, Gesch. der Attributtenlehre in der Jüd. Religionsphilosophie des Mittelaliers, pp. 95–115, Gotha, 1877;

- Löwenthal, Pseudo-Aristoteles über die Seele, Berlin, 1891;

- Müller, De Godsleer der Middeleeuwsche Joden, pp. 90–107, Groningen, 1898;

- Munk, Mélanges de Philosophie Juive et, Arabe, Paris, 1859;

- Myer, Qabbalah, The Philosophical Writings of . . . Avicebron, Philadelphia, 1888;

- Rosin, in J. Q. R. iii. 159–181;

- Sachs, Die Religiöse; Poesie der Juden in Spanien, pp. 213–248, Berlin, 1845;

- Seyerlen, Die Gegenseitigen Beziehungen Zwischen Abendländischer und Morgenländischer Wissenschaft mit Besonderer Rücksicht auf Solomon ibn Gebirol und Seine Philosophische Bedeutung, Jena, 1899;

- Stouössel, Salomo ben Gabirol als Philosoph und Förderer der Kabbala, Leipsic, 1881;

- Steinschneider, Hebr. Uebers. pp. 379–388, Berlin, 1893;

- Wise, The Improvement of the Moral Qualities, New York, 1901;

- Wittmann, Die Stellung des Heiligen Thomas von Aquin zu Avencebrol, Münster, 1900.

- For Poetry:

- Geiger, Salomo Gabirol und Seine Dichtungen, Leipsic, 1867;

- Senior Sachs, Cantiqucs de Salomon ibn Gabirole, Paris, 1868;

- idem, in Ha-Teḥiyyah, p. 185, Berlin, 1850;

- Dukes, Schire Shelomo, Hanover, 1858;

- idem, Ehrensaülen, Vienna, 1837;

- Edelmann and Dukes, Treasures of Oxford, London, 1851;

- M. Sachs, Die Religiöse Poesie der Juden in Spanien, Berlin, 1845;

- Zunz, Literaturgesch. pp. 187–194, 411, 588;

- Kämpf, Nichtandalusische Poesie Andalusischer Dichter, pp. 167 et seq.;

- Brody, Kuntras ha-Pijutim nach dem Machsor Vitry, Berlin, 1894, Index.

- Turner, William (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

[edit] Works by or about Solomon ibn Gabirol at Wikisource

Works by or about Solomon ibn Gabirol at Wikisource- Pessin, Sarah. "Solomon Ibn Gabirol". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (includes an extensive bibliography)

- An Andalusian Alphabet introduction to his poems

- Improvement of the Moral Qualities[permanent dead link] English translation at seforimonline.org

- Solomon Ibn Gabirol biography on chabad.org

- Traditional Sphardic Singing of Gabirol's Shabbat Poem Shimru Shabtotai

- pdf of Azharot of Solomon Ibn Gabirol in Hebrew

- Ibn Gabirol Digital digital humanities project on Ibn Gabirol's philosophical ideas