Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bacteroidales

View on Wikipedia

| Bacteroidales | |

|---|---|

| |

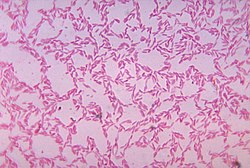

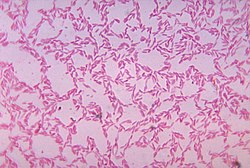

| Bacteroides biacutis anaerobically cultured in blood agar medium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Kingdom: | Pseudomonadati |

| Phylum: | Bacteroidota |

| Class: | Bacteroidia Krieg 2012[2] |

| Order: | Bacteroidales Krieg 2012[1] |

| Families[3][4][5] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Bacteroidales is an order of bacteria.[1][3] Notably it includes the genera Prevotella and Bacteroides , which are commonly found in the human gut microbiota.

Phylogeny

[edit]The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature[3] and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).[4]

| Whole-genome based phylogeny[6] | 16S rRNA based LTP_12_2021[7][8][9] | GTDB 07-RS207 by Genome Taxonomy Database[10][11][12] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Krieg NR (2010). "Order I. Bacteroidales ord. nov.". In Krieg NR, Staley JT, Brown DR, Hedlund BP, Paster BJ, Ward NL, Ludwig W, Whitman WB (eds.). Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. p. 25.

- ^ Krieg NR (2010). "Class I. Bacteroidia class. nov.". In Krieg NR, Staley JT, Brown DR, Hedlund BP, Paster BJ, Ward NL, Ludwig W, Whitman WB (eds.). Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. p. 25.

- ^ a b c Euzéby JP, Parte AC. "Bacteroidia". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN). Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Sayers; et al. "Bacteroidia". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) taxonomy database. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- ^ Parker, Charles Thomas; Garrity, George M (19 October 2017). Parker, Charles Thomas; Garrity, George M (eds.). "Williamwhitmaniaceae Pikuta et al. 2017 emend. García-López et al. 2019". NamesforLife. doi:10.1601/tx.30875.

- ^ García-López M, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Tindall BJ, Gronow S, Woyke T, Kyrpides NC, Hahnke RL, Göker M (2019). "Analysis of 1,000 Type-Strain Genomes Improves Taxonomic Classification of Bacteroidetes". Front Microbiol. 10: 2083. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.02083. PMC 6767994. PMID 31608019.

- ^ "The LTP". Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "LTP_all tree in newick format". Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "LTP_12_2021 Release Notes" (PDF). Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "GTDB release 07-RS207". Genome Taxonomy Database. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "ar53_r207.sp_label". Genome Taxonomy Database. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "Taxon History". Genome Taxonomy Database. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ Ormerod, Kate L.; Wood, David L. A.; Lachner, Nancy; Gellatly, Shaan L.; Daly, Joshua N.; Parsons, Jeremy D.; Dal'Molin, Cristiana G. O.; Palfreyman, Robin W.; Nielsen, Lars K.; Cooper, Matthew A.; Morrison, Mark; Hansbro, Philip M.; Hugenholtz, Philip (7 July 2016). "Genomic characterization of the uncultured Bacteroidales family S24-7 inhabiting the guts of homeothermic animals". Microbiome. 4 (1): 36. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0181-2. PMC 4936053. PMID 27388460.