Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Biogas

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Sustainable energy |

|---|

|

Biogas is a gaseous renewable energy source[1] produced from raw materials such as agricultural waste, manure, municipal waste, plant material, sewage, green waste, wastewater, and food waste. Biogas is produced by anaerobic digestion with anaerobic organisms or methanogens inside an anaerobic digester, biodigester or a bioreactor.[2][3]

The gas composition is primarily methane (CH

4) and carbon dioxide (CO

2) and may have small amounts of hydrogen sulfide (H

2S), moisture and siloxanes. The methane can be combusted or oxidized with oxygen. This energy release allows biogas to be used as a fuel; it can be used in fuel cells and for heating purpose, such as in cooking. It can also be used in a gas engine to convert the energy in the gas into electricity and heat.[4]

Biogas can be upgraded to natural gas quality specifications by stripping carbon dioxide and other contaminants. Biogas that has been upgraded to interchangeability with natural gas is called Renewable Natural Gas (RNG). RNG can be used a drop-in fuel in the gas grid or to produce compressed natural gas as a vehicle fuel.[5]

Biogas is considered to be a renewable resource. At a high level, biogas is a carbon neutral fuel in so far as emissions of carbon dioxide from its combustion are matched by carbon dioxide pulled from the atmosphere to produce biomass.[6] In practice, the carbon intensity of biogas can vary depending on emissions from the production of biomass and the processes used to produce and upgrade biogas.[5] In some applications, the capturing of biogas can avoid emissions of methane reducing overall emissions.[7]

Production

[edit]Biogas is produced by microorganisms, such as methanogens and sulfate-reducing bacteria, performing anaerobic respiration. Biogas can refer to gas produced naturally and industrially.

Natural

[edit]In soil, methane is produced in anaerobic environments by methanogens, but is mostly consumed in aerobic zones by methanotrophs. Methane emissions result when the balance favors methanogens. Wetland soils are the main natural source of methane. Other sources include oceans, forest soils, termites, and wild ruminants.[8]

Industrial

[edit]Anaerobic digestion is a sequence of processes by which microorganisms break down biodegradable material in the absence of oxygen.[9] This process produces biogas which can be used as a fuel. Industrial biogas production can either be purpose-built such as anaerobic digesters built to process manure and organic waste or can harvest biogas produced as byproduct from landfills or wastewater treatment plants.[10]

Biogas plants

[edit]A biogas plant is the name often given to an anaerobic digester that treats farm wastes, municipal organic waste and/or energy crops.[10] Industrial biogas plants process organic material in an air-tight tank to create anaerobic conditions. The material is heated to either mesothermic (~38oC) or thermophilic (>55oC) and held for a typical retention time of two to thirty days.[11]

These plants can be fed with energy crops such as maize silage or biodegradable wastes including sewage sludge and food waste. During the process, the micro-organisms transform biomass waste into biogas and digestate. Higher quantities of biogas can be produced when the wastewater is co-digested with other residuals from the dairy industry, sugar industry, or brewery industry. For example, while mixing 90% of wastewater from beer factory with 10% cow whey, the production of biogas was increased by 2.5 times compared to the biogas produced by wastewater from the brewery only.[12]

Landfill gas

[edit]

Landfill gas is produced by wet organic waste decomposing under anaerobic conditions in a similar way to biogas.[13][14]

The waste is covered and mechanically compressed by the weight of the material that is deposited above. This material prevents oxygen exposure thus allowing anaerobic microbes to thrive. Biogas builds up and is slowly released into the atmosphere if the site has not been engineered to capture the gas. Landfill gas released in an uncontrolled way can be hazardous since it can become explosive when it escapes from the landfill and mixes with oxygen. The lower explosive limit is 5% methane and the upper is 15% methane.[15]

The methane in biogas is 28[16] times more potent a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. Therefore, uncontained landfill gas, which escapes into the atmosphere may significantly contribute to the effects of global warming. In addition, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in landfill gas contribute to the formation of photochemical smog.[17]

Dangers

[edit]The air pollution produced by biogas is similar to that of natural gas as when methane (a major constituent of biogas) is ignited for its usage as an energy source, Carbon dioxide is made as a product which is a greenhouse gas ( as described by this equation: CH4 + 2O2 → CO2 + 2H2O ). The content of toxic hydrogen sulfide presents additional risks and has been responsible for serious accidents.[18] Leaks of unburned methane are an additional risk, because methane is a potent greenhouse gas. A facility may leak 2% of the methane.[19][20]

Biogas can be explosive when mixed in the ratio of one part biogas to 8–20 parts air. Special safety precautions have to be taken for entering an empty biogas digester for maintenance work. It is important that a biogas system never has negative pressure as this could cause an explosion. Negative gas pressure can occur if too much gas is removed or leaked; Because of this biogas should not be used at pressures below one column inch of water, measured by a pressure gauge.[citation needed]

Frequent smell checks must be performed on a biogas system. If biogas is smelled anywhere windows and doors should be opened immediately. If there is a fire the gas should be shut off at the gate valve of the biogas system.[21]

Composition

[edit]| Compound | Formula | Percentage by volume |

|---|---|---|

| Methane | CH 4 |

50–80 |

| Carbon dioxide | CO 2 |

15–50 |

| Nitrogen | N 2 |

0–10 |

| Hydrogen | H 2 |

0–1 |

| Hydrogen sulfide | H 2S |

0–0.5 |

| Oxygen | O 2 |

0–2.5 |

| Source: www.kolumbus.fi, 2007[22] | ||

The composition of biogas varies depending upon the substrate composition, as well as the conditions within the anaerobic reactor (temperature, pH, and substrate concentration).[23] Landfill gas typically has methane concentrations around 50%. Advanced waste treatment technologies can produce biogas with 55–75% methane,[24] which for reactors with free liquids can be increased to 80–90% methane using in-situ gas purification techniques.[25] As produced, biogas contains water vapor. The fractional volume of water vapor is a function of biogas temperature; correction of measured gas volume for water vapour content and thermal expansion is easily done via simple mathematics[26] which yields the standardized volume of dry biogas.

For 1000 kg (wet weight) of input to a typical biodigester, total solids may be 30% of the wet weight while volatile suspended solids may be 90% of the total solids. Protein would be 20% of the volatile solids, carbohydrates would be 70% of the volatile solids, and finally fats would be 10% of the volatile solids.

Biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) is a measure of the amount of oxygen required by aerobic micro-organisms to decompose the organic matter in a sample of material being used in the biodigester as well as the BOD for the liquid discharge allows for the calculation of the daily energy output from a biodigester.

Contaminants

[edit]Sulfur compounds

[edit]Toxic, corrosive and foul smelling hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) is the most common contaminant in biogas. If not separated, combustion will produce sulfur dioxide (SO

2) and sulfuric acid (H

2SO

4), which are corrosive and environmentally hazardous.,[27] Other sulfur-containing compounds, such as thiols may be present.

Ammonia

[edit]Ammonia (NH

3) is produced from organic compounds containing nitrogen, such as the amino acids in proteins. If not separated from the biogas, combustion results in NO

x emissions.[27]

Siloxanes

[edit]In some cases, biogas contains siloxanes. They are formed from the anaerobic decomposition of materials commonly found in soaps and detergents. During combustion of biogas containing siloxanes, silicon is released and can combine with free oxygen or other elements in the combustion gas. Deposits are formed containing mostly silica (SiO

2) or silicates (Si

xO

y) and can contain calcium, sulfur, zinc, phosphorus. Such white mineral deposits accumulate to a surface thickness of several millimeters and must be removed by chemical or mechanical means.

Debate

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Renewable energy |

|---|

|

Arguments in favor

[edit]High levels of methane are produced when manure is stored under anaerobic conditions. During storage and when manure has been applied to the land, nitrous oxide is also produced as a byproduct of the denitrification process. Nitrous oxide (N

2O) is 273 times more aggressive as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide and methane 27 times more than carbon dioxide.[16]

By converting cow manure into methane biogas via anaerobic digestion, the millions of cattle in the United States would be able to produce 100 billion kilowatt hours of electricity, enough to power millions of homes across the United States. One cow can produce enough manure in one day to generate 3 kilowatt hours of electricity.[28] Furthermore, by converting cattle manure into methane biogas instead of letting it decompose, global warming gases could be reduced by 99 million metric tons or 4%.[29]

Arguments against

[edit]Others environmental groups have argued that manure based biogases are a form of greenwashing. They argue it encourages and subsidies the use of concentrated animal feeding operations and emits other pollutants such as hydrogen sulfide.[30] In 2022, 6 US senators including Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren argued biogas would not be able to succeed without taxpayer dollars and that those would be better used on other methods. They also argued that they may accelerate consolidation in the industry and see farms expand their size specifically to be large enough to receive biogas subsidies. They point to evidence farmers did this following California's rollout of biogas incentive programs.[31] Others have argued the level of funding to biogas is already particularly outsized. For instance, in Wisconsin, just two years (2022-2023) of spending on biogas has been higher than 12 years of spending on solar energy.[32]

Manufacturing of biogas from intentionally planted maize has been described as being unsustainable and harmful due to very concentrated, intense and soil eroding character of these plantations.[33]

Applications

[edit]

Biogas can be used for electricity production on sewage works,[34] in a CHP gas engine, where the waste heat from the engine is conveniently used for heating the digester; cooking; space heating; water heating; and process heating. If compressed, it can replace compressed natural gas for use in vehicles, where it can fuel an internal combustion engine or fuel cells and is a much more effective displacer of carbon dioxide than the normal use in on-site CHP plants.[34][35][36]

Biogas upgrading

[edit]Raw biogas produced from digestion is roughly 60% methane and 39% CO

2 with trace elements of H

2S: inadequate for use in machinery. The corrosive nature of H

2S alone is enough to destroy the mechanisms.[27]

Methane in biogas can be concentrated via a biogas upgrader to the same standards as fossil natural gas, which itself has to go through a cleaning process, and becomes biomethane. If the local gas network allows, the producer of the biogas may use their distribution networks. Gas must be very clean to reach pipeline quality and must be of the correct composition for the distribution network to accept. Carbon dioxide, water, hydrogen sulfide, and particulates must be removed if present.[27]

There are four main methods of upgrading: water washing, pressure swing absorption, selexol absorption, and amine gas treating.[37] In addition to these, the use of membrane separation technology for biogas upgrading is increasing, and there are already several plants operating in Europe and USA.[27][38]

The most prevalent method is water washing where high pressure gas flows into a column where the carbon dioxide and other trace elements are scrubbed by cascading water running counter-flow to the gas. This arrangement could deliver 98% methane with manufacturers guaranteeing maximum 2% methane loss in the system. It takes roughly between 3% and 6% of the total energy output in gas to run a biogas upgrading system.

Biogas gas-grid injection

[edit]Gas-grid injection is the injection of biogas into the methane grid (natural gas grid) is possible if biogas is upgraded to biomethane. Until the breakthrough of micro combined heat and power two-thirds of all the energy produced by biogas power plants was lost (as heat). Using the grid to transport the gas to consumers, the energy can be used for on-site generation,[39] resulting in a reduction of losses in the transportation of energy. Typical energy losses in natural gas transmission systems range from 1% to 2%; in electricity transmission they range from 5% to 8%.[40]

Before being injected in the gas grid, biogas passes a cleaning process, during which it is upgraded to natural gas quality. During the cleaning process trace components harmful to the gas grid and the final users are removed.[41]

Biogas in transport

[edit]

If concentrated and compressed, it can be used in vehicle transportation. Compressed biogas is becoming widely used in Sweden, Switzerland, and Germany. A biogas-powered train, named Biogaståget Amanda (The Biogas Train Amanda), has been in service in Sweden since 2005.[42][43] Biogas powers automobiles. In 1974, a British documentary film titled Sweet as a Nut detailed the biogas production process from pig manure and showed how it fueled a custom-adapted combustion engine.[44][45] In 2007, an estimated 12,000 vehicles were being fueled with upgraded biogas worldwide, mostly in Europe.[46]

Biogas is part of the wet gas and condensing gas (or air) category that includes mist or fog in the gas stream. The mist or fog is predominately water vapor that condenses on the sides of pipes or stacks throughout the gas flow. Biogas environments include wastewater digesters, landfills, and animal feeding operations (covered livestock lagoons).

Ultrasonic flow meters are one of the few devices capable of measuring in a biogas atmosphere. Most of thermal flow meters are unable to provide reliable data because the moisture causes steady high flow readings and continuous flow spiking, although there are single-point insertion thermal mass flow meters capable of accurately monitoring biogas flows with minimal pressure drop. They can handle moisture variations that occur in the flow stream because of daily and seasonal temperature fluctuations, and account for the moisture in the flow stream to produce a dry gas value.

Biogas generated heat/electricity

[edit]Biogas can be used in different types of internal combustion engines, such as the Jenbacher or Caterpillar gas engines.[47] Other internal combustion engines such as gas turbines are suitable for the conversion of biogas into both electricity and heat. The digestate is the remaining inorganic matter that was not transformed into biogas. It can be used as an agricultural fertiliser.

Biogas can be used as the fuel in the system of producing biogas from agricultural wastes and co-generating heat and electricity in a combined heat and power (CHP) plant. Unlike the other green energy such as wind and solar, the biogas can be quickly accessed on demand. The global warming potential can also be greatly reduced when using biogas as the fuel instead of fossil fuel.[48]

However, the acidification and eutrophication potentials produced by biogas are 25 and 12 times higher respectively than fossil fuel alternatives. This impact can be reduced by using correct combination of feedstocks, covered storage for digesters and improved techniques for retrieving escaped material. Overall, the results still suggest that using biogas can lead to significant reduction in most impacts compared to fossil fuel alternative. The balance between environmental damage and green house gas emission should still be considered while implicating the system.[49]

Technological advancements

[edit]Projects such as NANOCLEAN are nowadays developing new ways to produce biogas more efficiently, using iron oxide nanoparticles in the processes of organic waste treatment. This process can triple the production of biogas.[50]

Wastewater Treatment

[edit]Faecal Sludge is a product of onsite sanitation systems. Post collection and transportation, Faecal sludge can be treated with sewage in a conventional treatment plant, or otherwise it can be treated independently in a faecal sludge treatment plant. Faecal sludge can also be co-treated with organic solid waste in composting or in an anaerobic digestion system.[51] Biogas can be generated through anaerobic digestion in the treatment of faecal sludge.

The appropriate management of excreta and its valorisation through the production of biogas from faecal sludge helps mitigate the effects of poorly managed excreta such as waterborne diseases and water and environmental pollution.[52]

The Resource Recovery and Reuse is a subprogram of the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems dedicated to applied research on the safe recovery of water, nutrients and energy from domestic and agro-industrial waste streams.[53] They believe using waste as energy would be good financially and would tackle sanitation, health and environmental issues.

Legislation

[edit]European Union

[edit]The European Union has legislation regarding waste management and landfill sites called the Landfill Directive.

Countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany now have legislation in force that provides farmers with long-term revenue and energy security.[54]

The EU mandates that internal combustion engines with biogas have ample gas pressure to optimize combustion, and within the European Union ATEX centrifugal fan units built in accordance with the European directive 2014–34/EU (previously 94/9/EG) are obligatory. These centrifugal fan units, for example Combimac, Meidinger AG or Witt & Sohn AG are suitable for use in Zone 1 and 2 .

United States

[edit]The United States legislates against landfill gas as it contains VOCs. The United States Clean Air Act and Title 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) requires landfill owners to estimate the quantity of non-methane organic compounds (NMOCs) emitted. If the estimated NMOC emissions exceeds 50 tonnes per year, the landfill owner is required to collect the gas and treat it to remove the entrained NMOCs. That usually means burning it. Because of the remoteness of landfill sites, it is sometimes not economically feasible to produce electricity from the gas.[55]

There are a variety of grants and loans the support the development of anaerobic digestor systems. The Rural Energy for American Program provides loan financing and grant funding for biogas systems, as does the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, Conservation Stewardship Program, and Conservation Loan Program.[56]

Global developments

[edit]United States

[edit]With the many benefits of biogas, it is starting to become a popular source of energy and is starting to be used in the United States more.[57] In 2003, the United States consumed 43 TWh (147 trillion BTU) of energy from "landfill gas", about 0.6% of the total U.S. natural gas consumption.[46] Methane biogas derived from cow manure is being tested in the U.S. According to a 2008 study, collected by the Science and Children magazine, methane biogas from cow manure would be sufficient to produce 100 billion kilowatt hours enough to power millions of homes across America. Furthermore, methane biogas has been tested to prove that it can reduce 99 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions or about 4% of the greenhouse gases produced by the United States.[58]

The number of farm-based digesters increased by 21% in 2021 according to the American Biogas Council.[59] In Vermont biogas generated on dairy farms was included in the CVPS Cow Power program. The program was originally offered by Central Vermont Public Service Corporation as a voluntary tariff and now with a recent merger with Green Mountain Power is now the GMP Cow Power Program. Customers can elect to pay a premium on their electric bill, and that premium is passed directly to the farms in the program. In Sheldon, Vermont, Green Mountain Dairy has provided renewable energy as part of the Cow Power program. It started when the brothers who own the farm, Bill and Brian Rowell, wanted to address some of the manure management challenges faced by dairy farms, including manure odor, and nutrient availability for the crops they need to grow to feed the animals. They installed an anaerobic digester to process the cow and milking center waste from their 950 cows to produce renewable energy, a bedding to replace sawdust, and a plant-friendly fertilizer. The energy and environmental attributes are sold to the GMP Cow Power program. On average, the system run by the Rowells produces enough electricity to power 300 to 350 other homes. The generator capacity is about 300 kilowatts.[60]

In Hereford, Texas, cow manure is being used to power an ethanol power plant. By switching to methane biogas, the ethanol power plant has saved 1000 barrels of oil a day. Over all, the power plant has reduced transportation costs and will be opening many more jobs for future power plants that will rely on biogas.[61]

In Oakley, Kansas, an ethanol plant considered to be one of the largest biogas facilities in North America is using integrated manure utilization system to produce heat for its boilers by utilizing feedlot manure, municipal organics and ethanol plant waste. At full capacity the plant is expected to replace 90% of the fossil fuel used in the manufacturing process of ethanol and methanol.[62][63]

In California, the Southern California Gas Company has advocated for mixing biogas into existing natural gas pipelines. However, California state officials have taken the position that biogas is "better used in hard-to-electrify sectors of the economy-- like aviation, heavy industry and long-haul trucking".[64]

Europe

[edit]

The level of development varies greatly in Europe. While countries such as Germany, Austria, Sweden and Italy are fairly advanced in their use of biogas, there is a vast potential for this renewable energy source in the rest of the continent, especially in Eastern Europe. MT-Energie is a German biogas technology company operating in the field of renewable energies.[65] Different legal frameworks, education schemes and the availability of technology are among the prime reasons behind this untapped potential.[66] Another challenge for the further progression of biogas has been negative public perception.[67]

In February 2009, the European Biogas Association (EBA) was founded in Brussels as a non-profit organisation to promote the deployment of sustainable biogas production and use in Europe. EBA's strategy defines three priorities: establish biogas as an important part of Europe's energy mix, promote source separation of household waste to increase the gas potential, and support the production of biomethane as vehicle fuel. In July 2013, it had 60 members from 24 countries across Europe.[68]

UK

[edit]As of September 2013[update], there are about 130 non-sewage biogas plants in the UK. Most are on-farm, and some larger facilities exist off-farm, which are taking food and consumer wastes.[69]

On 5 October 2010, biogas was injected into the UK gas grid for the first time. Sewage from over 30,000 Oxfordshire homes is sent to Didcot sewage treatment works, where it is treated in an anaerobic digestor to produce biogas, which is then cleaned to provide gas for approximately 200 homes.[70]

In 2015 the Green-Energy company Ecotricity announced their plans to build three grid-injecting digesters.[71]

Italy

[edit]In Italy the biogas industry first started in 2008, thanks to the introduction of advantageous feed tariffs. They were later replaced by feed-in premiums and the preference was given to by products and farming waste and leading to stagnation in biogas production and derived heat and electricity since 2012.[72]As of September 2018[update], in Italy there are more than 200 biogas plants with a production of about 1.2 GW[73][74][75]

Germany

[edit]Germany is Europe's biggest biogas producer[76] and the market leader in biogas technology.[77] In 2010 there were 5,905 biogas plants operating throughout the country: Lower Saxony, Bavaria, and the eastern federal states are the main regions.[78] Most of these plants are employed as power plants. Usually the biogas plants are directly connected with a CHP which produces electric power by burning the bio methane. The electrical power is then fed into the public power grid.[79] In 2010, the total installed electrical capacity of these power plants was 2,291 MW.[78] The electricity supply was approximately 12.8 TWh, which is 12.6% of the total generated renewable electricity.[80]

Biogas in Germany is primarily extracted by the co-fermentation of energy crops (called 'NawaRo', an abbreviation of nachwachsende Rohstoffe, German for renewable resources) mixed with manure. The main crop used is corn. Organic waste and industrial and agricultural residues such as waste from the food industry are also used for biogas generation.[81] In this respect, biogas production in Germany differs significantly from the UK, where biogas generated from landfill sites is most common.[76]

Biogas production in Germany has developed rapidly over the last 20 years. The main reason is the legally created frameworks. Government support of renewable energy started in 1991 with the Electricity Feed-in Act (StrEG). This law guaranteed the producers of energy from renewable sources the feed into the public power grid, thus the power companies were forced to take all produced energy from independent private producers of green energy.[82] In 2000 the Electricity Feed-in Act was replaced by the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG). This law even guaranteed a fixed compensation for the produced electric power over 20 years. The amount of around 8 ¢/kWh gave farmers the opportunity to become energy suppliers and gain a further source of income.[81]

The German agricultural biogas production was given a further push in 2004 by implementing the so-called NawaRo-Bonus. This is a special payment given for the use of renewable resources, that is, energy crops.[83] In 2007 the German government stressed its intention to invest further effort and support in improving the renewable energy supply to provide an answer on growing climate challenges and increasing oil prices by the 'Integrated Climate and Energy Programme'.

This continual trend of renewable energy promotion induces a number of challenges facing the management and organisation of renewable energy supply that has also several impacts on the biogas production.[84] The first challenge to be noticed is the high area-consuming of the biogas electric power supply. In 2011 energy crops for biogas production consumed an area of circa 800,000 ha in Germany.[85] This high demand of agricultural areas generates new competitions with the food industries that did not exist hitherto. Moreover, new industries and markets were created in predominately rural regions entailing different new players with an economic, political and civil background. Their influence and acting has to be governed to gain all advantages this new source of energy is offering. Finally biogas will furthermore play an important role in the German renewable energy supply if good governance is focused.[84]

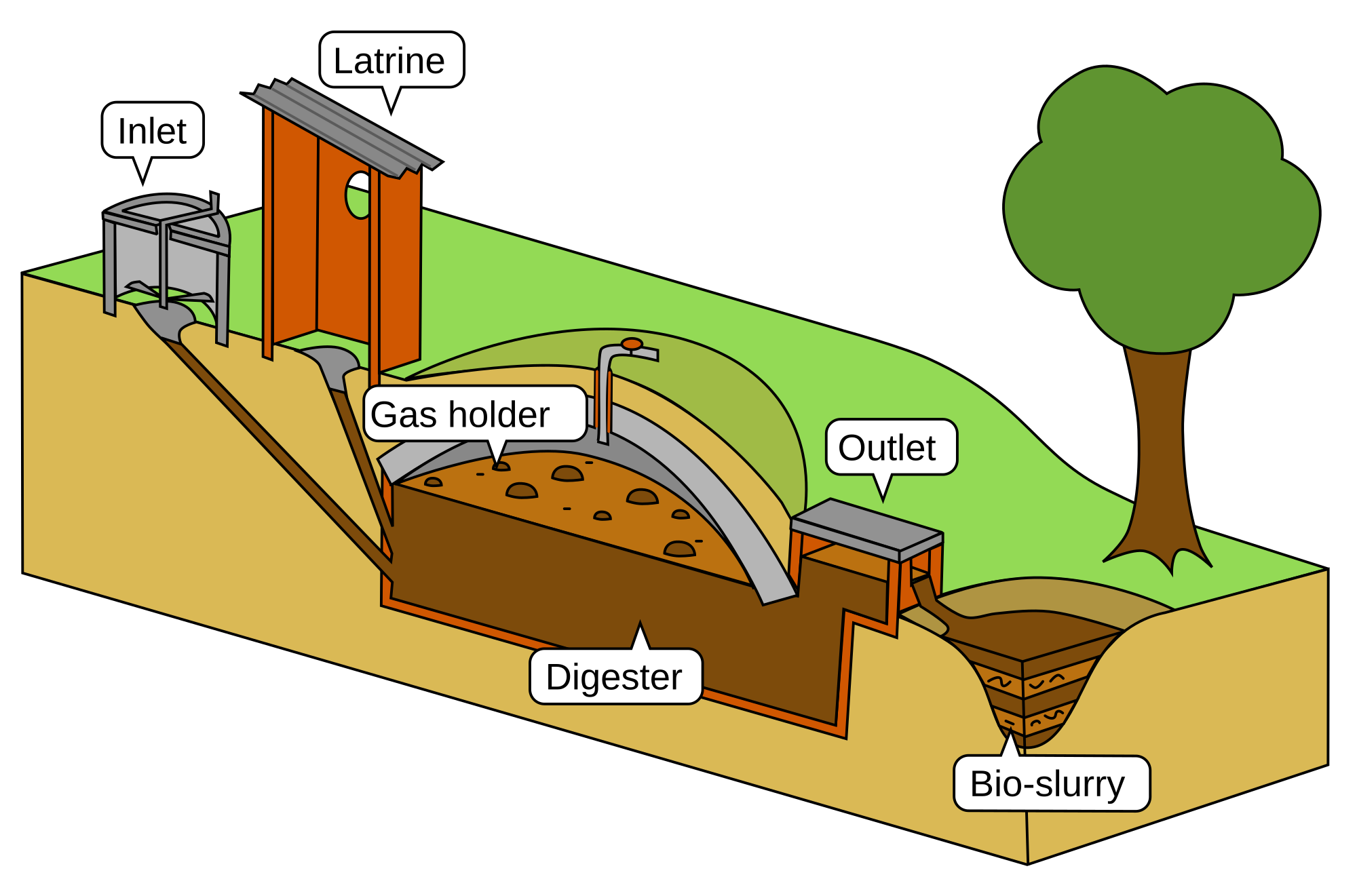

Developing countries

[edit]Domestic biogas plants convert livestock manure and night soil into biogas and slurry, the fermented manure. This technology is feasible for small-holders with livestock producing 50 kg manure per day, an equivalent of about 6 pigs or 3 cows. This manure has to be collectable to mix it with water and feed it into the plant. Toilets can be connected. Another precondition is the temperature that affects the fermentation process. With an optimum at 36 °C the technology especially applies for those living in a (sub) tropical climate. This makes the technology for small holders in developing countries often suitable.[86]

Depending on size and location, a typical brick made fixed dome biogas plant can be installed at the yard of a rural household with the investment between US$300 to $500 in Asian countries and up to $1400 in the African context.[87] A high quality biogas plant needs minimum maintenance costs and can produce gas for at least 15–20 years without major problems and re-investments. For the user, biogas provides clean cooking energy, reduces indoor air pollution, and reduces the time needed for traditional biomass collection, especially for women and children. The slurry is a clean organic fertilizer that potentially increases agricultural productivity.[86] In developing countries, it was also determined that the use of biogas leads to a 20% reduction in GHG emissions compared with GHG emissions due to firewood. Moreover, GHG emissions of 384.1 kg CO2 equivalent per year per animal could be prevented.[88]

Energy is an important part of modern society and can serve as one of the most important indicators of socio-economic development. As much as there have been advancements in technology, even so, some three billion people, primarily in the rural areas of developing countries, continue to access their energy needs for cooking through traditional means by burning biomass resources like firewood, crop residues and animal dung in crude traditional stoves.[89]

Domestic biogas technology is a proven and established technology in many parts of the world, especially Asia.[90] Several countries in this region have embarked on large-scale programmes on domestic biogas, such as China[91] and India.

The Netherlands Development Organisation, SNV,[92] supports national programmes on domestic biogas that aim to establish commercial-viable domestic biogas sectors in which local companies market, install and service biogas plants for households. In Asia, SNV is working in Nepal,[93] Vietnam,[94][95] Bangladesh,[96] Bhutan, Cambodia,[96] Lao PDR,[97] Pakistan[98] and Indonesia,[99] and in Africa; Rwanda,[100] Senegal, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia,[101] Tanzania,[102] Uganda, Kenya,[103] Benin and Cameroon.

In South Africa a prebuilt Biogas system is manufactured and sold. One key feature is that installation requires less skill and is quicker to install as the digester tank is premade plastic.[104]

India

[edit]Biogas in India[105] has been traditionally based on dairy manure as feed stock and these "gobar" gas plants have been in operation for a long period of time, especially in rural India. In the last 2–3 decades, research organisations with a focus on rural energy security have enhanced the design of the systems resulting in newer efficient low cost designs such as the Deenabandhu model.

The Deenabandhu Model is a new biogas-production model popular in India. (Deenabandhu means "friend of the helpless".) The unit usually has a capacity of 2 to 3 cubic metres. It is constructed using bricks or by a ferrocement mixture. In India, the brick model costs slightly more than the ferrocement model; however, India's Ministry of New and Renewable Energy offers some subsidy per model constructed.

Biogas which is mainly methane/natural gas can also be used for generating protein rich cattle, poultry and fish feed in villages economically by cultivating Methylococcus capsulatus bacteria culture with tiny land and water foot print.[106][107][108] The carbon dioxide gas produced as by product from these plants can be put to use in cheaper production of algae oil or spirulina from algaculture particularly in tropical countries like India which can displace the prime position of crude oil in near future.[109][110] Union government of India is implementing many schemes to utilise productively the agro waste or biomass in rural areas to uplift rural economy and job potential.[111][112] With these plants, the non-edible biomass or waste of edible biomass is converted in to high value products without any water pollution or green house gas (GHG) emissions.[113]

LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas) is a key source of cooking fuel in urban India and its prices have been increasing along with the global fuel prices. Also the heavy subsidies provided by the successive governments in promoting LPG as a domestic cooking fuel has become a financial burden renewing the focus on biogas as a cooking fuel alternative in urban establishments. This has led to the development of prefabricated digester for modular deployments as compared to RCC and cement structures which take a longer duration to construct. Renewed focus on process technology like the Biourja process model[114] has enhanced the stature of medium and large scale anaerobic digester in India as a potential alternative to LPG as primary cooking fuel.

In India, Nepal, Pakistan and Bangladesh biogas produced from the anaerobic digestion of manure in small-scale digestion facilities is called gobar gas; it is estimated that such facilities exist in over 2 million households in India, 50,000 in Bangladesh and thousands in Pakistan, particularly North Punjab, due to the thriving population of livestock. The digester is an airtight circular pit made of concrete with a pipe connection. The manure is directed to the pit, usually straight from the cattle shed. The pit is filled with a required quantity of wastewater. The gas pipe is connected to the kitchen fireplace through control valves. The combustion of this biogas has very little odour or smoke. Owing to simplicity in implementation and use of cheap raw materials in villages, it is one of the most environmentally sound energy sources for rural needs. One type of these system is the Sintex Digester. Some designs use vermiculture to further enhance the slurry produced by the biogas plant for use as compost.[115]

In Pakistan, the Rural Support Programmes Network is running the Pakistan Domestic Biogas Programme[116] which has installed 5,360 biogas plants[117] and has trained in excess of 200 masons on the technology and aims to develop the Biogas Sector in Pakistan.

In Nepal, the government provides subsidies to build biogas plant at home.

China

[edit]As of at least 2023, China is both the world's largest producer and largest consumer of household biogas.[118]: 172

The Chinese have experimented with the applications of biogas since 1958. Around 1970, China had installed 6,000,000 digesters in an effort to make agriculture more efficient. During the last few years, technology has met high growth rates. This seems to be the earliest developments in generating biogas from agricultural waste.[119]

The rural biogas construction in China has shown an increased development trend. The exponential growth of energy supply caused by rapid economic development and severe haze condition in China have led biogas to become the better eco-friendly energy for the rural areas. In Qing county, Hebei Province, the technology of using crop straw as a main material to generate biogas is currently developing.[120]

China had 26.5 million biogas plants, with an output of 10.5 billion cubic meter biogas until 2007. The annual biogas output has increased to 248 billion cubic meter in 2010.[121] The Chinese government had supported and funded rural biogas projects.[122] As of 2023, more than 30 million rural Chinese households use biogas digesters.[118]: 172

During the winter, the biogas production in northern regions of China is lower. This is caused by the lack of heat control technology for digesters thus the co-digestion of different feedstock failed to complete in the cold environment.[123]

Zambia

[edit]Lusaka, the capital city of Zambia, has two million inhabitants with over half of the population residing in peri-urban areas. The majority of this population use pit latrines as toilets generating approximately 22,680 tons of fecal sludge per annum. This sludge is inadequately managed: Over 60% of the generated faecal sludge remains within the residential environment thereby compromising both the environment and public health.[124]

In the face of research work and implementation of biogas having started as early as in the 1980s, Zambia is lagging behind in the adoption and use of biogas in the sub-Saharan Africa. Animal manure and crop residues are required for the provision of energy for cooking and lighting. Inadequate funding, absence of policy, regulatory framework and strategies on biogas, unfavorable investor monetary policy, inadequate expertise, lack of awareness of the benefits of biogas technology among leaders, financial institutions and locals, resistance to change due cultural and traditions of the locals, high installation and maintenance costs of biogas digesters, inadequate research and development, improper management and lack of monitoring of installed digesters, complexity of the carbon market, lack of incentives and social equity are among the challenges that have impeded the acquiring and sustainable implementation of domestic biogas production in Zambia.[125]

Associations

[edit]- World Biogas Association (https://www.worldbiogasassociation.org/)

- Anaerobic Digestion and Bioresources Association (United Kingdom) (https://adbioresources.org/)

- American Biogas Council (https://americanbiogascouncil.org/)

- Canadian Biogas Association (https://www.biogasassociation.ca/)

- European Biogas Association[126]

- German Biogas Association[127]

- Indian Biogas Association[128]

Society and culture

[edit]In the 1985 Australian film Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome the post-apocalyptic settlement Barter town is powered by a central biogas system based upon a piggery. As well as providing electricity, methane is used to power Barter's vehicles.

"Cow Town",[clarification needed] written in the early 1940s, discusses the travails of a city vastly built on cow manure and the hardships brought upon by the resulting methane biogas. Carter McCormick, an engineer from a town outside the city, is sent in to figure out a way to utilize this gas to help power, rather than suffocate the city.[citation needed]

Contemporary biogas production provides new opportunities for skilled employment, drawing on the development of new technologies.[129]

See also

[edit]- Anaerobic digestion – Processes by which microorganisms break down biodegradable material in the absence of oxygen

- Biochemical oxygen demand – Oxygen needed to remove organics from water

- Biodegradability – Decomposition by living organisms

- Bioenergy – Renewable energy made from biomass

- Biofuel – Fuel derived from biological sources

- Biohydrogen – Hydrogen that is produced biologically

- Hydrogen economy – Using hydrogen to decarbonize more sectors

- Landfill gas monitoring – Process of monitoring gas from landfills.

- Methanation – Conversion of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide (COx) to methane (CH4)

- MSW/LFG (municipal solid waste and landfill gas)

- Natural gas – Gaseous fossil fuel

- Renewable energy – Energy collected from renewable resources

- Renewable natural gas – Methane enriched biogas that can easily be upgraded

- Relative cost of electricity generated by different sources – Comparison of costs of different electricity generation sources

- Thermal hydrolysis

- Waste management – Activities and actions required to manage waste from its source to its final disposal

- European Biomass Association – European bioenergy organisation

References

[edit]- ^ National Non-Food Crops Centre. "NNFCC Renewable Fuels and Energy Factsheet: Anaerobic Digestion" Archived 10 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on 2011-02-16

- ^ Webdesign, Insyde. "How does biogas work?". www.simgas.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ Mao, Chunlan; Feng, Yongzhong; Wang, Xiaojiao; Ren, Guangxin (2015). "Review on research achievements of biogas from anaerobic digestion". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 45: 540–555. Bibcode:2015RSERv..45..540M. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.02.032.

- ^ "Biogas & Engines". clarke-energy.com. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Canada Energy Regulator (24 November 2023). "CER – Market Snapshot: Two Decades of Growth in Renewable Natural Gas in Canada". www.cer-rec.gc.ca. Retrieved 20 October 2025.

- ^ "Are Biofuels Carbon Neutral? Feedstocks & Applications". 29 July 2025. Retrieved 20 October 2025.

- ^ Liebetrau, J., Ammenberg, J., Gustafsson, M., Pelkmans, L., Murphy, J.D. (2022). The role ofbiogas and biomethane in pathway to net zero. Murphy, J.D (Ed.) IEA Bioenergy Task 37, 2022

- ^ Le Mer, Jean; Roger, Pierre (January 2001). "Production, oxidation, emission and consumption of methane by soils: A review". European Journal of Soil Biology. 37 (1): 25–50. Bibcode:2001EJSB...37...25L. doi:10.1016/S1164-5563(01)01067-6. S2CID 62815957.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (18 March 2019). "How Does Anaerobic Digestion Work?". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 27 October 2025.

- ^ a b "An introduction to biogas and biomethane – Outlook for biogas and biomethane: Prospects for organic growth – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 27 October 2025.

- ^ "Anaerobic Digesters: Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). Alberta Department of Agriculture. May 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2025.

- ^ Appels, Lise; Baeyens, Jan; Degrève, Jan; Dewil, Raf (2008). "Principles and potential of the anaerobic digestion of waste-activated sludge". Progress in Energy and Combustion Science. 34 (6): 755–781. Bibcode:2008PECS...34..755A. doi:10.1016/j.pecs.2008.06.002. ISSN 0360-1285. S2CID 95588169. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Biogas – Bioenergy Association of New Zealand (BANZ)". Bioenergy.org.nz. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ LFG energy projects Archived 3 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Safety Page, Beginners Guide to Biogas Archived 17 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, www.adelaide.edu.au/biogas. Retrieved 22.10.07.

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Gupta, Sujata (3 November 2010). "Cold climates no bar to biogas production". New Scientist. London: Sunita Harrington. p. 14.

- ^ Hedlund, FH; Madsen, M (2018). "Incomplete understanding of biogas chemical hazards – Serious gas poisoning accident while unloading food waste at biogas plant" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Health & Safety. 25 (6): 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.jchas.2018.05.004. S2CID 67849856.

- ^ Reinelt, Torsten; Liebetrau, Jan (January 2020). "Monitoring and Mitigation of Methane Emissions from Pressure Relief Valves of a Biogas Plant". Chemical Engineering & Technology. 43 (1): 7–18. doi:10.1002/ceat.201900180. S2CID 208716124.

- ^ Michael Fredenslund, Anders; Gudmundsson, Einar; Maria Falk, Julie; Scheutz, Charlotte (February 2023). "The Danish national effort to minimise methane emissions from biogas plants". Waste Management. 157: 321–329. Bibcode:2023WaMan.157..321M. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2022.12.035. PMID 36592586. S2CID 254174784.

- ^ "Biogas Problems". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Basic Information on Biogas Archived 6 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine, www.kolumbus.fi. Retrieved 2.11.07.

- ^ Hafner, Sasha (2017). "Predicting methane and biogas production with the biogas package" (PDF). CRAN.

- ^ "Juniper". Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Richards, B.; Herndon, F. G.; Jewell, W. J.; Cummings, R. J.; White, T. E. (1994). "In situ methane enrichment in methanogenic energy crop digesters". Biomass and Bioenergy. 6 (4): 275–282. Bibcode:1994BmBe....6..275R. doi:10.1016/0961-9534(94)90067-1. hdl:1813/60790.

- ^ Richards, B.; Cummings, R.; White, T.; Jewell, W. (1991). "Methods for kinetic analysis of methane fermentation in high solids biomass digesters". Biomass and Bioenergy. 1 (2): 65–73. Bibcode:1991BmBe....1...65R. doi:10.1016/0961-9534(91)90028-B. hdl:1813/60787.

- ^ a b c d e Abatzoglou, Nicolas; Boivin, Steve (2009). "A review of biogas purification processes". Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining. 3 (1): 42–71. doi:10.1002/bbb.117. ISSN 1932-104X. S2CID 84907789.

- ^ State Energy Conservation Office (Texas). "Biomass Energy: Manure for Fuel." State Energy Conservation Office (Texas). State of Texas, 23 April 2009. Web. 3 October 2009.

- ^ Webber, Michael E and Amanda D Cuellar. "Cow Power. In the News: Short News Items of Interest to the Scientific Community." Science and Children os 46.1 (2008): 13. Gale. Web. 1 October 2009 in United States.

- ^ Udasin, Sharon (23 October 2024). "California subsidies for manure-based biogas face rising scrutiny over pollution concerns". The Hill. Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 8 August 2025.

- ^ "Markey, Booker, Gillibrand, Sanders, Warren Urge EPA and USDA to Limit New Incentives for Factory Farm Biodigesters | U.S. Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts". www.markey.senate.gov. Retrieved 8 August 2025.

- ^ Redman, Henry (2 January 2024). "Proposed anaerobic digester in Waupaca County stirs local controversy • Wisconsin Examiner". Wisconsin Examiner. Retrieved 8 August 2025.

- ^ "How a false solution to climate change is damaging the natural world | George Monbiot". the Guardian. 14 March 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ a b Administrator. "Biogas CHP – Alfagy – Profitable Greener Energy via CHP, Cogen and Biomass Boiler using Wood, Biogas, Natural Gas, Biodiesel, Vegetable Oil, Syngas and Straw". Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Mertins, Anica; Wawer, Tim (2022). "How to use biogas?: A systematic review of biogas utilization pathways and business models". Bioresources and Bioprocessing. 9 (1): 59. doi:10.1186/s40643-022-00545-z. PMC 10992758. PMID 38647793.

- ^ Kabeyi, Moses Jeremiah Barasa; Olanrewaju, Oludolapo Akanni (2022). "Biogas Production and Applications in the Sustainable Energy Transition". Journal of Energy. 2022: 1–43. doi:10.1155/2022/8750221.

- ^ "Nyheter – SGC". Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Petersson A., Wellinger A. (2009). Biogas upgrading technologies – developments and innovations. IEA Bioenergy Task 37 Archived 29 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Biogas Flows Through Germany's Grid Big Time – Renewable Energy News Article". 14 March 2012. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "energy loss, transmission loss". Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Adding gas from biomass to the gas grid" (PDF). Swedish Gas Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Biogas train in Sweden Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Friendly fuel trains (30 October 2005) New Straits Times, p. F17.

- ^ "Bates Car – Sweet As a Nut (1975)". BFI. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ National Film Board of Canada. "Bate's Car: Sweet as a Nut". NFB.ca. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ a b What is biogas?, U.S. Department of Energy, 13 April 2010

- ^ State Energy Conservation Office (Texas). "Biomass Energy: Manure for Fuel." Archived 23 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 23 April 2009. Web. 3 October 2009.

- ^ Comparison of energy systems using life cycle assessment. World Energy Council. 2004. ISBN 0-946121-16-8. OCLC 59190792.

- ^ Whiting, Andrew; Azapagic, Adisa (2014). "Life cycle environmental impacts of generating electricity and heat from biogas produced by anaerobic digestion". Energy. 70: 181–193. Bibcode:2014Ene....70..181W. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2014.03.103. ISSN 0360-5442.

- ^ "Creating BIOGAS+: a new technology to improve the efficiency and profitability in the treatment of biowaste". SIOR. Social Impact Open Repository. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ Semiyaga, Swaib; Okure, Mackay A. E.; Niwagaba, Charles B.; Katukiza, Alex Y.; Kansiime, Frank (1 November 2015). "Decentralized options for faecal sludge management in urban slum areas of Sub-Saharan Africa: A review of technologies, practices and end-uses". Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 104: 109–119. Bibcode:2015RCR...104..109S. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.09.001. ISSN 0921-3449.

- ^ Hidenori Harada; Linda Strande; Shigeo Fujii (2016). "Challenges and Opportunities of Faecal Sludge Management for Global Sanitation". Kaisei Publishing, Tokyo: 81–100.

- ^ Otoo, M.; Drechsel, P.; Danso, G.; Gebrezgabher, S.; Rao, K.; Madurangi, G. (2016). Testing the implementation potential of resource recovery and reuse business models: from baseline surveys to feasibility studies and business plans (Report). International Water Management Institute (IWMI). CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE). doi:10.5337/2016.206. hdl:10568/75885.

- ^ "CHP | Combined Heat and Power | Cogeneration | Wood Biomass Gasified Co-generation | Energy Efficiency | Electricity Generation". Alfagy.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (15 April 2016). "Basic Information about Landfill Gas". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ Lazenby, Ruthie (15 August 2022). "Rethinking Manure Biogas: Policy Considerations to Promote Equity and Protect the Climate and Environment" (PDF). Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ "Inflation Reduction Act Gives a Boost to the Biogas Sector". The National Law Review. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ Cuellar, Amanda D and Michael E Webber (2008). "Cow power: the energy and emissions benefits of converting manure to biogas". Environ. Res. Lett. 3 (3) 034002. Bibcode:2008ERL.....3c4002C. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/3/3/034002. hdl:2152/20290.

- ^ Moran, Barbara (9 November 2022). "Massachusetts companies are turning to 'anaerobic digesters' to dispose of food waste". NPR News. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Zezima, Katie. "Electricity From What Cows Leave Behind." The New York Times, 23 September 2008, natl. ed.: SPG9. Web. 1 October 2009.

- ^ State Energy Conservation Office (Texas). "Biomass Energy: Manure for Fuel Archived 23 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine." State Energy Conservation Office (Texas). State of Texas, 23 April 2009. Web. 3 October 2009.

- ^ Trash-to-energy trend boosts anaerobic digesters [1]."

- ^ Western Plains Energy finishing up North America's largest biogas digester [2]."

- ^ McKenna, Phil (13 November 2019). "Fearing for Its Future, a Big Utility Pushes 'Renewable Gas,' Urges Cities to Reject Electrification". InsideClimate News. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "Renewables - Made in Germany". German Energy Agency. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ^ "About SEBE". Archived from the original on 28 November 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "FNR: Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe e. V." (PDF). Retrieved 17 June 2016. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "European Biogas Association". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ The Official Information Portal on AD 'Biogas Plant Map'

- ^ Sewage project sends first ever renewable gas to grid Thames Water Archived 9 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ecotricity announces third Green Gasmill". www.ecotricity.co.uk. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ Eyl-Mazzega, Mark Antione; Mathieu, Carole (27 October 2020). "Biogas and Biomethane in Europe: Lessons from Denmark, Italy and Germany" (PDF). Études de l'Ifri. [permanent dead link]

- ^ ANSA Ambiente & Energia Installed biogas power in Italy

- ^ AuCo Solutions biogas software Biogas software solution Archived 25 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Snam IES Biogas Biogas Plant in Italy Archived 25 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "European Biogas Barometer" (PDF). EurObserv'ER. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ "Biogas". BMU. Archived from the original on 29 January 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Biogas Segments Statistics 2010" (PDF). Fachverband Biogas e.V. Retrieved 5 November 2011. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Biomass for Power Generation and CHP" (PDF). IEA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ "Renewable Energy Sources". 6 September 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ a b Wieland, P. (2003). "Production and Energetic Use of Biogas from Energy Crops and Wastes in Germany". Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 109 (1–3): 263–274. doi:10.1385/abab:109:1-3:263. PMID 12794299. S2CID 9468552.

- ^ "Erneuerbare Energien in Deutschland. Rückblick und Stand des Innovationsgeschehens" (PDF). IfnE et al. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Wieland, P. (2006). "Biomass Digestion in Agriculture: A Successful Pathway for the Energy Production and Waste Treatment in Germany". Engineering in Life Sciences. 6 (3). Engineering in Life Science: 302–309. Bibcode:2006EngLS...6..302W. doi:10.1002/elsc.200620128. S2CID 54685767.

- ^ a b Kanning, H.; et al. (2009). "Erneuerbare Energien – Räumliche Dimensionen, neue Akteurslandschaften und planerische (Mit)Gestaltungspotenziale am Beispiel des Biogaspfades". Raumforschung und Raumordnung. 67 (2): 142–156. doi:10.1007/BF03185702.

- ^ "Cultivation of renewable Resources in Germany". FNR. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ a b Roubík, Hynek; Mazancová, Jana; Banout, Jan; Verner, Vladimír (20 January 2016). "Addressing problems at small-scale biogas plants: a case study from central Vietnam". Journal of Cleaner Production. 112 (Part 4): 2784–2792. Bibcode:2016JCPro.112.2784R. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.114.

- ^ Ghimire, Prakash C. (1 January 2013). "SNV supported domestic biogas programmes in Asia and Africa". Renewable Energy. Selected papers from World Renewable Energy Congress – XI. 49: 90–94. Bibcode:2013REne...49...90G. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2012.01.058.

- ^ Roubík, Hynek; Barrera, Sergio; Van Dung, Dinh; Phung, Le Dinh; Mazancová, Jana (10 October 2020). "Emission reduction potential of household biogas plants in developing countries: The case of central Vietnam". Journal of Cleaner Production. 270 122257. Bibcode:2020JCPro.27022257R. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122257. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Surendra, K. C.; Takara, Devin; Hashimoto, Andrew G.; Khanal, Samir Kumar (1 March 2014). "Biogas as a sustainable energy source for developing countries: Opportunities and challenges". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 31: 846–859. Bibcode:2014RSERv..31..846S. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2013.12.015. ISSN 1364-0321.

- ^ "SNV World". Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "China – Biogas". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Renewable energy". Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Biogas Sector Partnership-Nepal". Bspnepal.org.np. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ Roubík, H.; Mazancová, J.; Phung, L.D.; Banout, J. (2018). "Current approach to manure management for small-scale Southeast Asian farmers - Using Vietnamese biogas and non-biogas farms as an example". Renewable Energy. 115 (115): 362–370. Bibcode:2018REne..115..362R. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2017.08.068.

- ^ "Dự án chương trình khí sinh học cho ngành chăn nuôi Việt Nam". Biogas.org.vn. Archived from the original on 25 October 2004. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ a b http://www.idcol.org (click 'Projects')

- ^ "Home". Biogaslao.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ "SNV World". Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Indonesia Domestic Biogas Programme Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Renewable Energy". Snvworld.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Renewable energy". Snvworld.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ SNV Tanzania Domestic Biogas Programme Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Biogas First in Kenya for Clarke Energy and Tropical Power Accessed 11 September 2013

- ^ "Renewable Energy Solutions – Living Lightly". Renewable Energy Solutions. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "GPS Renewables – Waste management through biogas". GPS Renewables. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "BioProtein Production" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Le Page, Michael. "Food made from natural gas will soon feed farm animals – and us". New Scientist. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "New venture selects Cargill's Tennessee site to produce Calysta FeedKind Protein". Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Algenol and Reliance launch algae fuels demonstration project in India". Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ "ExxonMobil Announces Breakthrough in Renewable Energy". Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ "Indrapratha Gas, Mahindra & Mahindra join hands to stop stubble burning". Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ "Modi govt plans Gobar-Dhan scheme to convert cattle dung into energy". Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Assessment of environmental impact of FeedKind protein" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ "GPS Renewables – Monitoring Methodology". GPS Renewables. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Biogas plants provide cooking and fertiliser". Ashden Awards, sustainable and renewable energy in the UK and developing world. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "PAK-ENERGY SOLUTION". Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "5,360 bio-gas plants installed in 12 districts". Business Recorder. 27 December 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ a b Santos, Gonçalo (2021). Chinese Village Life Today: Building Families in an Age of Transition. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-74738-5.

- ^ Biogas in China. Retrieved 27 October 2016

- ^ Hu, Die (2015). "Hebei Province Qing County Straw Partnerships Biogas Application and Promotion Research". Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Mechatronics, Electronic, Industrial and Control Engineering. Paris, France: Atlantis Press. doi:10.2991/meic-15.2015.260. ISBN 978-94-6252-062-2.

- ^ Deng, Yanfei; Xu, Jiuping; Liu, Ying; Mancl, Karen (2014). "Biogas as a sustainable energy source in China: Regional development strategy application and decision making". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 35: 294–303. Bibcode:2014RSERv..35..294D. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.04.031. ISSN 1364-0321.

- ^ Chen, Yu; Yang, Gaihe; Sweeney, Sandra; Feng, Yongzhong (2010). "Household biogas use in rural China: A study of opportunities and constraints". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 14 (1): 545–549. Bibcode:2010RSERv..14..545C. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2009.07.019. ISSN 1364-0321. S2CID 154461345.

- ^ He, Pin Jing (2010). "Anaerobic digestion: An intriguing long history in China". Waste Management. 30 (4): 549–550. Bibcode:2010WaMan..30..549H. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2010.01.002. ISSN 0956-053X. PMID 20089392.

- ^ Tembo, J.M.; Nyirenda, E.; Nyambe, I. (2017). "Enhancing faecal sludge management in peri-urban areas of Lusaka through faecal sludge valorisation: challenges and opportunities". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 60 (1) 012025. Bibcode:2017E&ES...60a2025T. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/60/1/012025.

- ^ Shane, Agabu; Gheewala, Shabbir H (2020). "Potential, Barriers and Prospects of Biogas Production in Zambia" (PDF). Journal of Sustainable Energy & Environment. 6 (2015) 21-27.

- ^ "European Biogas Association". Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "German Biogas Association". Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "Biogas-india – Home". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Generating new employment opportunities [Social Impact]". SIOR. Social Impact Open Repository. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Updated Guidebook on Biogas Development. United Nations, New York, (1984) Energy Resources Development Series No. 27. p. 178, 30 cm.

- Book: Biogas from Waste and Renewable Resources. WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, (2008) Dieter Deublein and Angelika Steinhauser

- A Comparison between Shale Gas in China and Unconventional Fuel Development in the United States: Health, Water and Environmental Risks by Paolo Farah and Riccardo Tremolada. This is a paper presented at the Colloquium on Environmental Scholarship 2013 hosted by Vermont Law School (11 October 2013)

- Marchaim, Uri (1992). Biogas processes for sustainable development. FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-103126-1.

- Woodhead Publishing Series. (2013). The Biogas Handbook: Science, Production and Applications. ISBN 978-0857094988

- Mustafa, Mohamad Y.; Calay, Rajnish K.; Román, E. (2016). "Biogas from Organic Waste - A Case Study". Procedia Engineering. 146: 310–317. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2016.06.397. hdl:10037/10459.

- Lazenby, Ruthie (15 August 2022). "Rethinking Manure Biogas: Policy Considerations to Promote Equity and Protect the Climate and Environment" (PDF). Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- Abanades, S.; Abbaspour, H.; Ahmadi, A.; Das, B.; Ehyaei, M. A.; Esmaeilion, F.; El Haj Assad, M.; Hajilounezhad, T.; Jamali, D. H.; Hmida, A.; Ozgoli, H. A.; Safari, S.; AlShabi, M.; Bani-Hani, E. H. (2022). "A critical review of biogas production and usage with legislations framework across the globe". International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology. 19 (4): 3377–3400. Bibcode:2022JEST...19.3377A. doi:10.1007/s13762-021-03301-6. PMC 8124099. PMID 34025745.

- Jameel, Mohammed Khaleel; Mustafa, Mohammed Ahmed; Ahmed, Hassan Safi; Mohammed, Amira jassim; Ghazy, Hameed; Shakir, Maha Noori; Lawas, Amran Mezher; Mohammed, Saad khudhur; Idan, Ameer Hassan; Mahmoud, Zaid H.; Sayadi, Hamidreza; Kianfar, Ehsan (2024). "Biogas: Production, properties, applications, economic and challenges: A review". Results in Chemistry. 7 101549. doi:10.1016/j.rechem.2024.101549.

External links

[edit]Biogas

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

Biogas is a renewable fuel gas generated through the anaerobic decomposition of organic matter by microorganisms in an oxygen-deprived environment.[1] This process, known as anaerobic digestion, converts biodegradable materials such as animal manure, crop residues, food waste, and sewage sludge into a mixture primarily composed of methane (CH₄) and carbon dioxide (CO₂).[14] Unlike aerobic decomposition, which produces odors and incomplete breakdown, anaerobic digestion yields a combustible gas suitable for energy recovery while stabilizing the waste and reducing pathogens.[5] The fundamental principle of biogas production relies on a series of microbial reactions occurring in four sequential stages within a sealed digester: hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis.[5] In hydrolysis, hydrolytic bacteria break down complex polymers like carbohydrates, proteins, and fats into simpler monomers such as sugars and amino acids. Acidogenesis follows, where acidogenic bacteria ferment these monomers into volatile fatty acids, alcohols, hydrogen, and CO₂. Acetogenic bacteria then convert the fermentation products into acetic acid, hydrogen, and CO₂, setting the stage for methanogenic archaea to produce methane from acetate or through the reduction of CO₂ with hydrogen.[1] Optimal conditions for these reactions include mesophilic (around 35–40°C) or thermophilic (50–60°C) temperatures, neutral pH (6.8–7.2), sufficient retention time (15–30 days), and a carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of 20:1 to 30:1 to prevent process inhibition.[5] The chemical composition of biogas typically ranges from 50–70% methane, 30–50% carbon dioxide, with trace amounts (0–3%) of hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), nitrogen, hydrogen, and water vapor, varying based on feedstock and digestion conditions.[15] Methane imparts the fuel value, with biogas having a calorific value of approximately 20–25 MJ/m³, about 60% that of natural gas, enabling its use in heating, electricity generation, or as vehicle fuel after purification.[16] Impurities like H₂S can corrode equipment, necessitating removal for upgraded biomethane, which exceeds 95% CH₄ purity.[17]| Component | Typical Range (%) |

|---|---|

| Methane (CH₄) | 50–70 |

| Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) | 30–50 |

| Hydrogen Sulfide (H₂S) | 0–3 |

| Other traces (N₂, H₂, H₂O) | <5 |

Chemical Composition and Properties

Biogas primarily consists of methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2), with methane typically ranging from 45% to 65% by volume in raw form, depending on feedstock type, digestion temperature, and process efficiency.[18] [7] Carbon dioxide constitutes 30% to 50% of the mixture, while trace components include nitrogen (0-10%), hydrogen sulfide (H2S, 0-1%), ammonia (NH3, <1%), hydrogen (H2, <1%), and water vapor (1-10%).[19] [20] These proportions can vary; for instance, biogas from manure digestion often yields 55-65% methane, whereas landfill-derived gas may have lower methane (45-60%) due to slower decomposition and inert gas dilution.[20] [21] The presence of hydrogen sulfide imparts a characteristic rotten-egg odor and contributes to corrosiveness, necessitating removal for long-term storage or pipeline injection.[15] Nitrogen and oxygen levels, if elevated above 1-2%, reduce energy yield by acting as diluents, often resulting from air ingress during production.[22] Advanced upgrading processes can increase methane content to 90-99%, producing renewable natural gas with composition akin to fossil natural gas (primarily CH4 >95%).[18] Physically, biogas has a density of approximately 1.1-1.3 kg/m³ at standard conditions, slightly less than or comparable to air (1.29 kg/m³), allowing it to rise if CO2 content is low.[23] Its lower heating value ranges from 18-26 MJ/m³, correlating directly with methane fraction—for 60% CH4, it approximates 21.5 MJ/Nm³ or 5,700-6,000 kcal/m³—lower than pure methane (35.8 MJ/m³) due to inert CO2.[24] [25] Biogas is combustible within 5-15% volume in air, with a flame temperature of 1,900°C, but impurities like H2S can produce toxic emissions (e.g., SO2) during combustion without scrubbing.[26] It is stored as a gas under pressure or liquefied at -162°C, though raw biogas requires drying to prevent hydrate formation in pipelines.[22]History

Ancient and Pre-Modern Uses

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the ancient Assyrians harnessed biogas from the anaerobic decomposition of organic matter to heat bathwater as early as the 10th century BC.[27] Comparable informal uses of flammable gases from waste decay for heating persisted in regions like Persia by the 16th century.[27] These early applications relied on natural emanations from sewers, manure pits, or marshes rather than engineered systems, reflecting rudimentary recognition of methane-rich gas as a combustible resource.[28] In the 17th century, Flemish chemist Jan Baptist van Helmont documented the production of flammable vapors from fermenting organic materials, providing early scientific observation of biogas formation, though practical utilization remained limited to sporadic collection.[28] By the mid-19th century, more deliberate production emerged; in 1859, the first recorded anaerobic digestion facility was established at the Matunga Leper Asylum in Bombay (present-day Mumbai), India, where human excreta was processed to generate biogas specifically for illuminating lamps.[26] This installation marked an initial shift toward controlled digestion for targeted energy needs, predating widespread industrial adoption.[29]20th Century Developments

In the early 20th century, biogas production advanced through the construction of the first large-scale plant in Birmingham, England, in 1911, which treated urban sewage sediments and generated biogas for practical use.[30] German engineers Karl Imhoff and colleagues patented innovations, including permanent heating systems for digesters, between 1914 and 1921, improving process stability and efficiency in wastewater treatment.[30] By the 1930s, researchers identified anaerobic bacteria as the primary agents of methane production and determined optimal digestion conditions, such as temperature and pH, enabling more reliable biogas yields from organic wastes.[31] These developments coincided with the establishment of modern facilities, primarily linked to municipal sewage processing in Europe and the United States.[32] World War II (1939–1945) marked a surge in biogas application due to acute petroleum shortages, with Germany extensively converting sewage and manure into fuel for vehicles, machinery, and stationary engines, producing up to 300 cubic meters daily from facilities processing manure from 180 livestock units.[33][34] France and other European nations similarly prioritized biogas fermentation to offset energy deficits, integrating it into agricultural and waste management systems.[30] Post-war, operational digesters persisted in Europe, sustaining interest in biogas as a supplemental energy source amid reconstruction efforts.[27] From the 1950s onward, biogas technology proliferated in developing regions, with India launching programs for low-cost rural household digesters to convert animal manure into cooking fuel and lighting gas, leading to thousands of installations by decade's end.[30] Intensive research during this period refined plant designs, such as fixed-dome models suited to small-scale operations, while early experiments in the United States explored crop residues as feedstocks for enhanced methanation.[35][36] The 1970s oil crises further accelerated adoption, particularly in China and India, where millions of domestic plants were disseminated by the century's close, driven by energy security needs and waste-to-energy synergies in agriculture-heavy economies.[37][32]Post-2000 Expansion

Following the enactment of supportive renewable energy policies in the early 2000s, global biogas production expanded markedly, quadrupling from 78 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2000 to 364 TWh by 2017.[38] This growth continued, reaching 38.1 billion cubic meters (equivalent to 1.46 exajoules) by 2020, driven primarily by installations in Europe, the United States, and China. [39] Key enablers included feed-in tariffs, subsidies, and mandates for renewable energy integration into grids and gas networks, which incentivized the scaling of anaerobic digestion facilities from small household units to large industrial plants.[40] In Europe, particularly Germany and Denmark, biogas adoption surged post-2000 due to national policies aligned with EU renewable directives. Germany's Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG) of 2000 provided guaranteed tariffs for biogas-derived electricity, leading to a continuous rise in biogas plants from fewer than 100 in 2000 to over 9,000 by 2015.[40] Denmark, building on earlier experiments, expanded centralized biogas plants integrated with district heating and transport fuels, supported by energy taxes and subsidies that positioned biogas as a key renewable contributor, accounting for a growing share of the country's renewable energy mix by the 2010s.[41] By 2021, the EU hosted approximately 18,843 biogas plants producing 159 TWh annually.[42] The EU's Renewable Energy Directive II (2018) further bolstered this by setting binding targets for renewables, including bioenergy, though foundational growth predated it.[43] In Asia, China's rural biogas programs catalyzed massive deployment of household digesters. The 2003 National Rural Biogas Construction program subsidized installations, propelling the number from under 10 million in 2000 to over 40 million by the mid-2010s, serving nearly 120 million rural residents with cooking and lighting fuel while reducing reliance on traditional biomass.[44] [45] Government investments totaling 61 billion yuan from 2003 to 2010 covered about one-third of construction costs per unit, fostering widespread adoption despite challenges like maintenance in colder regions.[46] [47] This initiative positioned China as a global leader in small-scale biogas, contributing significantly to the sector's overall post-2000 volume.[48] By the 2020s, upgrading biogas to biomethane for grid injection and transport fuels gained traction worldwide, with around 700 such plants operational globally by 2019, reflecting technological maturation and policy emphasis on higher-value applications.[49] The biogas plant market, valued at $4.18 billion in 2023, underscored ongoing commercialization, projected to double by 2032 amid demands for decarbonized gases.[50]Production Methods

Natural Processes

Biogas arises naturally through anaerobic microbial decomposition of organic matter in oxygen-limited environments, where bacteria and archaea sequentially hydrolyze complex substrates into simpler compounds, ferment them into volatile fatty acids and alcohols, convert these to acetate and hydrogen, and finally produce methane via methanogenesis. This multi-stage process, occurring without human intervention, yields a gas mixture typically comprising 50-70% methane (CH₄), 30-50% carbon dioxide (CO₂), and trace gases like hydrogen sulfide (H₂S).[7][51] Wetlands, including marshes, swamps, and peatlands, represent a primary natural locus for biogas production, as water saturation creates anoxic conditions conducive to methanogenic archaea such as Methanosarcina and Methanosaeta species, which reduce CO₂ with H₂ or disproportionate acetate to CH₄ and CO₂. These ecosystems, spanning roughly 5-8% of global land area, emit an estimated 145-185 teragrams (Tg) of methane annually, accounting for about 20-30% of total natural methane flux and contributing to atmospheric CH₄ levels that have risen from pre-industrial ~0.7 ppm to over 1.9 ppm by 2020.[52][53] In ruminant animals like cattle, sheep, and deer, biogas forms as a byproduct of enteric fermentation in the rumen, a foregut compartment hosting symbiotic methanogens (Methanobrevibacter spp.) that consume H₂ and CO₂ generated by protozoa and bacteria digesting fibrous plant carbohydrates such as cellulose. This process sustains rumen pH and microbial efficiency but releases 80-120 liters of methane per kilogram of dry matter intake, with global ruminant emissions totaling approximately 90 Tg CH₄ per year, primarily through eructation.[54][55] Other unmanaged natural sources include termite guts, where hindgut methanogens decompose lignocellulose, and ocean sediments, where buried organic carbon undergoes slow anaerobic breakdown; collectively, non-wetland, non-ruminant natural emissions contribute around 50-100 Tg CH₄ annually, underscoring the ubiquity of methanogenesis in carbon cycling. Unpiled animal manure and decaying biomass in forests or soils can also generate localized biogas under wet, compacted conditions, though yields are diffuse and often oxidized before release.[56][57]Anaerobic Digestion Systems