Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Battle of Magnesia

View on Wikipedia

| Battle of Magnesia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman–Seleucid War | |||||||

Illustration of a bronze plaque from Pergamon, likely depicting the Battle of Magnesia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Seleucid Empire | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

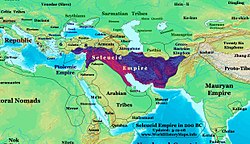

Location of the Battle of Magnesia | |||||||

The Battle of Magnesia took place in either December 190 or January 189 BC. It was fought as part of the Roman–Seleucid War, pitting forces of the Roman Republic led by the consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus and the allied Kingdom of Pergamon under Eumenes II against a Seleucid army of Antiochus III the Great. The two armies initially camped northeast of Magnesia ad Sipylum in Asia Minor (modern-day Manisa, Turkey), attempting to provoke each other into a battle on favorable terrain for several days.

When the battle finally began, Eumenes managed to throw the Seleucid left flank into disarray. While Antiochus' cavalry overpowered his adversaries on the right flank of the battlefield, his army's center collapsed before he could reinforce it. Modern estimates give 10,000 dead for the Seleucids and 5,000 killed for the Romans. The battle resulted in a decisive Roman-Pergamene victory, which led to the Treaty of Apamea that ended Seleucid domination in Asia Minor.

Background

[edit]Following his return from his Bactrian (210-209 BC)[1] and Indian (206-205 BC)[2] campaigns, Antiochus forged an alliance with Philip V of Macedon, seeking to jointly conquer the territories of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. In 198 BC, he was victorious in the Fifth Syrian War, taking over Coele-Syria and securing his southeastern border. He then focused his attention on Asia Minor, launching a successful campaign against coastal Ptolemaic possessions.[3] In 196 BC, Antiochus used the opportunity of Attalus I's death to assault cities controlled by the Attalid dynasty. Fearing that Antiochus would seize the entirety of Asia Minor, the independent cities of Smyrna and Lampsacus appealed for protection from the Roman Republic.[4] In the early spring of 196 BC, Antiochus' troops crossed to the European side of the Hellespont and began rebuilding the strategically important city of Lysimachia. In October 196 BC, Antiochus met with a delegation of Roman diplomats in Lysimachia. The Romans demanded that Antiochus withdraw from Europe and restore the autonomous status of Greek city-states in Asia Minor. Antiochus countered by claiming that he was simply rebuilding the empire of his ancestor Antiochus II Theos and criticized the Romans for meddling in the affairs of the Asia Minor states whose rights were traditionally defended by Rhodes.[5]

In late winter 196/195 BC, Rome's erstwhile chief enemy, Carthaginian general Hannibal, fled from Carthage to Antiochus' court in Ephesus. Despite the emergence of a pro-war party led by Scipio Africanus, the Roman Senate exercised restraint. The Seleucids expanded their holdings in Thrace from Perinthus to Maroneia at the expense of the Thracian tribesmen. Negotiations between the Romans and the Seleucids resumed, coming to a standstill once again over differences between Greek and Roman law on the status of disputed territorial possessions. In the summer of 193 BC, a representative of the Aetolian League assured Antiochus that the Aetolians would take his side in a future war with Rome, while Antiochus gave tacit support to Hannibal's plans of launching an anti-Roman coup d'état in Carthage.[6] The Aetolians began spurring the Greek states to jointly revolt under Antiochus' leadership against the Romans, hoping to provoke a war between the two parties. The Aetolians then captured the strategically important port city of Demetrias, killing the key members of the local pro-Roman faction. In September 192 BC, the Aetolian general Thoantas arrived at Antiochus' court, convincing him to openly oppose the Romans in Greece. The Seleucids raised 10,000 infantry, 500 cavalry, 6 war elephants, and 300 ships for their campaign in Greece.[7]

Prelude

[edit]

The Seleucid fleet sailed via Imbros and Skiathos, arriving at Demetrias where Antiochus' army disembarked.[8] The Achaean League declared war on the Seleucids and Aetolians with the Romans following suit in November 192 BC. Antiochus forced Chalcis to open its gates to him, turning the city into his base of operations. Antiochus then shifted his attention towards rebuilding his alliance with Philip V of Macedon, which had been shattered after the latter was decisively defeated by the Romans at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC. Philip expected that the Romans would emerge victorious in the conflict and counted on territorial rewards as well as the writing off of war reparations that he owed them; the Seleucids could provide neither, so Antiochus' overtures were rejected and Philip aligned himself with the Romans. Between December 192 and March 191 BC, Antiochus campaigned in Thessaly and Acarnania.[9]

A combined counter-offensive conducted by the Romans and their Macedonian allies erased all of Antiochus' gains in Thessaly within a month. On 26 April 191 BC, the two sides faced off at the Battle of Thermopylae, where Antiochus' army suffered a devastating defeat and he returned to Ephesus shortly afterwards.[10] The Seleucids then attempted to destroy the Roman fleet before it could unite with those of Rhodes and the Attalids. However, the Roman fleet defeated the Seleucids in the Battle of Corycus in September 191 BC, enabling it to take control of several cities including Dardanus and Sestos on the Hellespont.[11] In May 190 BC, Antiochus invaded Pergamon, ravaging the countryside, besieging its capital and forcing Eumenes to return from Greece. In August 190 BC, the Rhodians defeated Hannibal's fleet at the Battle of the Eurymedon. A month later a combined Roman-Rhodean fleet defeated the Seleucids at the Battle of Myonessus. The Seleucids could no longer control the Aegean Sea, opening the way for a Roman invasion of Asia Minor.[12] Antiochus withdrew his armies from Thrace, while simultaneously offering to cover half of the Roman war expenses and accept the demands made in Lysimachia in 196 BC. By this time, however, the Romans were determined to crush the Seleucids once and for all.[13] As the Roman forces reached Maroneia, Antiochus began preparing for a final decisive battle.[14] The Romans advanced through Dardanus to the River Caecus where they united with Eumenes’ army.[13]

Armies

[edit]

The two main historical accounts of the battle come from Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita Libri and Appian’s Syriaca.[15] Both of these authors agree that the Roman army was about 30,000 men strong and the Seleucids fielded approximately 72,000 soldiers. However, modern historians disagree on the issue, with some believing the estimates in the primary sources, while others claim that the two armies might have each numbered some 50,000 men. Additionally, the Romans had 16 war elephants at their disposal, while the Seleucids fielded 54.[16][17][18] A popular anecdote regarding the array of the two armies is that Antiochus supposedly asked Hannibal whether his vast and well-armed formation would be enough for the Roman Republic, to which Hannibal tartly replied, "Quite enough for the Romans, however greedy they are."[19]

The left wing of the Seleucids was commanded by Antiochus' son Seleucus and his nephew Antipater. It was composed of Cyrtian slingers and Elymaean archers, 4,000 peltasts, 1,500 Illyrians, 1,500 Carians and Cilicians, and 1,000 Neocretans. The rest of the left wing consisted of 2,500 Galatian and 500 Tarentine light cavalry, 1,000 royal cavalry, 3,000 cataphracts, 2,000 Cappadocian infantry, 16 war elephants, and a miscellaneous force of 2,700 light infantry. The center was formed by a 16,000-strong Macedonian phalanx, commanded by Philip, the master of the elephants. It was deployed into ten 1,600-man taxeis, each 50 men wide and 32 men deep. Twenty war elephants were separated into pairs and deployed in the gaps between the taxeis, further supported by 1,500 Galatian and 1,500 Atian infantry. The right flank was led by Antiochus, consisting of 3,000 cataphracts, 1,000 agema cavalry, 1,000 argyraspides of the royal guard, 1,200 Dahae horse archers, 2,500 Mysian archers, 3,000 Cretan and Illyrian light infantry, 4,500 Cyrtian slingers and Elymaean archers as well as a reserve of 16 war elephants. Ahead of the main body, units of scythed chariots and a unit of camel-borne Arab archers were posted in front of the left flank, and to their immediate right, Minnionas and Zeuxis commanded 6,000 psiloi light infantry. The war camp was guarded by 7,000 of the least combat-ready Seleucid troops.[20][21]

The left wing of the Romans was commanded by the legate Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. It numbered 10,800 heavy infantrymen drawn from among the Romans and Rome's socii, along with four cavalry companies of 100 to 120 men. The center likewise consisted of 10,800 Roman and Latin heavy infantrymen commanded personally by Scipio. The Roman infantry was divided into three lines, with the youngest soldiers standing at the front, in a more open and flexible formation than their adversaries. The right flank was led by Eumenes and comprised 2,800 to 3,000 cavalry, the majority being Romans supplemented by an 800-man Pergamene force. Ahead of the Roman main force were 3,000 Achaean and Pergamene light infantry and 800 Cretan and Illyrian archers. The rearguard was formed by 2,000 Thracian and Macedonian volunteers and 16 African war elephants that were considered inferior to the Asian war elephants deployed by the Seleucids.[17][22][23]

Battle

[edit]The battle took place either in December 190 BC or January 189 BC.[13] The Romans advanced from Pergamon towards Thyatira where they expected to encounter Antiochus. Antiochus was determined to fight his adversaries on the ground of his own choosing, and his army marched from the direction of Sardis towards Magnesia ad Sipylum, camping 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) northeast of the city. Magnesia had already served as a battlefield for the Seleucids in 281 BC where they had emerged victorious in the Battle of Corupedium.[15] Upon learning that the Seleucids had left Thyatira, the Romans marched for five days towards the River Phrygios, camping north of the River Hermos,[24] 6.5 kilometres (4.0 mi) from the Seleucid camp. Antiochus dispatched a party of 1,000 Galatian and Dahae cavalry to lure the Romans into a more exposed position, but the Romans refused to be drawn out. Three days later,[17] the Romans moved their camp into a horseshoe-shaped plain some 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) from the Seleucid camp, which was surrounded by the Phrygios and Hermos rivers on three sides, by which the Romans hoped to limit the effectiveness of the Seleucid cavalry.[25] The Seleucids once again sent an elite 3,000-man detachment to harass the Romans.[17]

During the following five days, the two armies lined up for battle, without engaging each other. Scipio found himself in a zugzwang. He could not hope to win the battle by directly assaulting the heavily-fortified Seleucid camp, but by refusing to engage he risked having his supply lines cut by the numerically-superior enemy cavalry. Turning back would have caused Roman morale to plunge as campaigns were halted during the winter. Additionally, Scipio wished to achieve a decisive victory over the Seleucids before a new consul was sent out from Rome to replace him.[17] The Romans advanced to the point where the Phrygios made a 90-degree turn towards the north, leaving their right flank unprotected by the rivers.[25] Antiochus was satisfied with the location, accepting the Roman challenge on the dawn of the third day after the last Roman advance.[17]

The battle began on the Seleucid left flank when Eumenes sent forward his archers, slingers, and spearmen to harass the Seleucid scythed chariots. The latter began fleeing in panic after suffering heavy casualties, causing confusion among the camel-borne Arab archers and cataphracts positioned behind them. Eumenes then charged with his cavalry before the cataphracts could properly reorganize. The Roman and Pergamene cavalry broke through the Seleucid left flank, causing the cataphracts to flee to the Seleucid camp. The Galatians, Cappadocians, and mercenary infantry to the left of the phalanx faced a simultaneous attack from the Roman center and right, causing them to retreat and exposing the phalanx's left flank.[26][27]

On the Seleucid right flank, Antiochus led the attack with the cataphracts and agema cavalry facing the Latin infantry, while the argyraspides engaged the Roman legionaries. The Roman infantry broke ranks retreating to their camp where they were reinforced by the Thracians and Macedonians and subsequently rallied by tribune Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. Antiochus's cavalry was unsuitable for taking the camp and he became bogged down in the fighting while his forces were badly needed elsewhere.[26][28] In the center, the Seleucid phalanx held its ground against the Roman infantry, but it was not mobile enough to dislodge the enemy archers and slingers who bombarded it with projectiles.[27] It began a slow organized retreat, when the war elephants positioned between its taxeis panicked because of the projectiles, causing the phalanx to break formation.[29] The phalangites discarded their weapons and abandoned the battlefield. By the time Antiochus' cavalry had returned to reinforce the center his army had already dispersed. He gathered the surviving troops and retreated to Sardes while the Romans were busy looting his camp.[30]

Aftermath

[edit]

Antiochus' defeat at Magnesia marked the end of the Macedonian phalanx's dominance on Hellenistic period battlefields.[31] According to Livy 53,000 Seleucid soldiers perished, with 1,400 being captured alongside 15 elephants. By comparison, Livy claims that the Romans lost 349 men with many more wounded. Modern estimates give 10,000 dead for the Seleucids and 5,000 killed for the Romans.[citation needed] Shortly after arriving at Sardes, Antiochus learnt that Seleucus had survived the battle and headed to Apamea to meet him.[32] The defeat at Magnesia and the subsequent withdrawal of the Seleucid fleet from Ephesus to Patara led the garrisons of numerous cities including Sardes, Ephesus, Thyatira, and Magnesia ad Sipylum to surrender to the Romans. Antiochus dispatched Zeuxis and Antipater to the Romans, in order to secure a truce. The truce was signed at Sardes in January 189 BC, whereupon Antiochus agreed to abandon his claims on all lands west of the Taurus Mountains, paid a heavy war indemnity and promised to hand over Hannibal and other notable enemies of Rome from among his allies.[33]

The Romans sought to subjugate Asia Minor and punish Antiochus' allies, starting the Galatian War. In mainland Greece they suppressed the Athamanians and Aetolians who broke the terms of a previous truce.[34] During the summer of 189 BC, ambassadors from the Seleucid Empire, Pergamon, Rhodes, and other Asia Minor states held peace talks with the Roman Senate. Lycia and Caria were given to Rhodes, while the Attalids received Thrace and most of Asia Minor west of the Taurus. The independence of Asia Minor city-states that sided with the Romans before the Battle of Magnesia was guaranteed. Antiochus further agreed to withdraw all his troops from beyond the Taurus, and refuse passage and support to enemies of Rome. The conditions also included the requirement to hand over Hannibal, Thoantas, and twenty notables as hostages, destroy all his fleet apart from ten ships, and give Rome 40,500 modiuses of grain per year. The terms were put into effect in the summer of 188 BC with the signing of the Treaty of Apamea.[35]

References

[edit]- ^ Lerner 1999, pp. 45–48.

- ^ Overtoom 2020, p. 147.

- ^ Sartre 2006, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Sartre 2006, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 60–62.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, p. 64.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 74, 76–78.

- ^ a b c Sarikakis 1974, p. 78.

- ^ Grainger 2002, p. 307.

- ^ a b Bar-Kochva 1976, p. 163.

- ^ Grainger 2002, pp. 314, 321.

- ^ a b c d e f Sarikakis 1974, p. 80.

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. 144.

- ^ Hoyos 2005, p. 203.

- ^ Taylor 2013, pp. 142.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Grainger 2002, p. 321.

- ^ Taylor 2013, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Grainger 2002, p. 320.

- ^ a b Bar-Kochva 1976, p. 165.

- ^ a b Taylor 2013, p. 147.

- ^ a b Sarikakis 1974, p. 81.

- ^ Grainger 2002, p. 326.

- ^ Grainger 2002, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, p. 83.

- ^ Grainger 2002, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 87–89.

Sources

[edit]- Bar-Kochva, Bezalel (1976). The Seleucid Army: Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521206679.

- Grainger, John (2002). The Roman War of Antiochus the Great. Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004128408.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2005). Hannibal's Dynasty: Power and Politics in the Western Mediterranean, 247–183 BC. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415359580.

- Lerner, Jeffrey (1999). The Impact of Seleucid Decline on the Eastern Iranian Plateau: The Foundations of Arsacid Parthia and Graeco-Bactria. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 9783515074179.

- Overtoom, Nikolaus Leo (2020). Reign of Arrows: The Rise of the Parthian Empire in the Hellenistic Middle East. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190888329.

- Sarikakis, Theodoros (1974). "Το Βασίλειο των Σελευκιδών και η Ρώμη" [The Seleucid Kingdom and Rome]. In Christopoulos, Georgios A. & Bastias, Ioannis K. (eds.). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος Ε΄: Ελληνιστικοί Χρόνοι [History of the Greek Nation, Volume V: Hellenistic Period] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. pp. 55–91. ISBN 978-960-213-101-5.

- Sartre, Maurice (2006). Ελληνιστική Μικρασία: Aπο το Αιγαίο ως τον Καύκασο [Hellenistic Asia Minor: From the Aegean to the Caucaus] (in Greek). Athens: Patakis Editions. ISBN 9789601617565.

- Taylor, Michael (2013). Antiochus The Great. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 9781848844636.

Battle of Magnesia

View on GrokipediaHistorical Background

Roman-Seleucid War Origins

The Roman-Seleucid War originated from Rome's expanding influence in the eastern Mediterranean following its victory in the Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC), which was precipitated by Macedonian king Philip V's alliance with Carthage during the Second Punic War and his aggressive expansion into Greece and the Aegean islands. Roman intervention was prompted by appeals from Greek city-states against Philip's encroachments, culminating in his defeat at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC under the command of consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus. In the war's aftermath, Flamininus proclaimed the "freedom of the Greeks" at the Isthmian Games in 196 BC, dissolving Macedonian garrisons and fostering pro-Roman alignments, including the strengthening of the Achaean League as a formal Roman ally to counterbalance other Hellenistic powers.[4][5] This Roman consolidation in Greece directly clashed with Seleucid ambitions, as king Antiochus III had forged a secret alliance with Philip V in 203 BC—known as the Pact of the Kings—to partition the Ptolemaic Empire, with Antiochus targeting southern Syria and Philip eyeing the Aegean and western territories. Although the pact's immediate goals were disrupted by Philip's defeat, Antiochus, having completed his eastern anabasis (212–205 BC) to reclaim lost territories, pursued western expansion by invading Thrace in 196 BC, claiming it as ancestral Seleucid domain. Roman warnings that same year explicitly cautioned Antiochus against interfering in European affairs or Greek politics, demanding his withdrawal from areas under implicit Roman protection, but he pressed on, incorporating Thrace into his realm and eyeing further gains in the Balkans.[6][5][4] Tensions escalated through a series of diplomatic exchanges from 196 to 193 BC, highlighted by the 194 BC embassy led by Publius Sulpicius Galba and Publius Villius, where Roman envoys, including Villius and Scipio, reiterated demands for Antiochus to evacuate Thrace, relinquish claims to autonomous Greek cities in Asia Minor, and abstain from European interventions, viewing his actions as a violation of the post-Macedonian settlement. Antiochus countered by asserting Seleucid rights over Asia Minor and proposing negotiations, but his refusal to comply fueled Roman suspicions of broader Hellenistic threats to their sphere of influence. The crisis peaked in 192 BC when the Aetolian League—disgruntled with Roman dominance after the Macedonian War and having lost territories in the settlement—invited Antiochus to Greece as a "liberator" from Roman hegemony, prompting him to cross the Hellespont with an army, seize Demetrias, and advance into Thessaly. This incursion directly challenged Roman authority, leading the Roman Senate to declare war in the autumn of 192 BC, marking the formal onset of the Roman-Seleucid conflict.[5][4][5]Antiochus III's Eastern and Western Campaigns

Antiochus III ascended to the Seleucid throne in 223 BC amid significant internal instability, including a major rebellion in the eastern satrapies led by the satrap Molon of Media, who proclaimed himself king in 222 BC with support from the satrap of Persis.[7] Antiochus personally led a campaign to suppress this uprising, defeating Molon near the Tigris River in late 222 BC and restoring order in Mesopotamia by 220 BC.[8] These eastern challenges, compounded by the independent kingdoms that had emerged in Parthia and Bactria following earlier Seleucid losses, prompted Antiochus to launch his grand anabasis from 212 to 205 BC, a sweeping eastern expedition aimed at reconquering lost territories.[8] The anabasis began with the subjugation of Armenia in 212 BC, followed by an invasion of Parthia in 209 BC, where Antiochus besieged the Parthian king Arsaces II in his capital of Hecatompylos and forced his submission as a vassal.[8] Advancing further, he crossed the Hindu Kush into Bactria, where he faced Euthydemus I in a prolonged siege at Bactra from 208 to 206 BC, ultimately securing Bactria and Gandhara as tributary states through diplomacy and marriage alliances.[8] By 205 BC, having restored Seleucid suzerainty over these regions and extracted substantial tribute, including war elephants, Antiochus returned westward, earning the epithet "the Great" (Megas) for his achievements in reasserting imperial control.[8] Emboldened by these successes, Antiochus turned to western expansion, initiating the Fifth Syrian War against Ptolemaic Egypt in 202 BC to reclaim Coele-Syria and Phoenicia, territories long contested between the two powers.[9] Capitalizing on Ptolemaic internal turmoil after the death of Ptolemy IV, Antiochus advanced rapidly, culminating in the decisive victory at the Battle of Paneion in 200 BC, which secured Judea's submission and control over the southern Levant.[9] The war concluded with a peace treaty in 195 BC, in which Ptolemy V Epiphanes married Antiochus's daughter Cleopatra I Syra, ceding Coele-Syria and Phoenicia to the Seleucids while allowing Ptolemaic retention of core Egyptian lands.[9] Following this consolidation, Antiochus sought further gains in Europe, forging an alliance with Philip V of Macedon in 203 BC to partition Ptolemaic holdings—Antiochus targeting Coele-Syria in the southern Levant, while Philip aimed for Aegean islands.[10] In 197 BC, after Philip's defeat by Rome in the Second Macedonian War left Lysimacheia abandoned, Antiochus invaded Thrace, capturing the city in 196 BC and using it as a base to reassert Seleucid claims to European territories originally won by Seleucus I.[11] These bold moves into Greek affairs, building on his eastern and southern triumphs, ultimately provoked Roman intervention, leading to a declaration of war in 192 BC.[8]Prelude to the Battle

Key Diplomatic and Naval Conflicts

In late 192 BC, Antiochus III landed in Greece at the invitation of the Aetolian League, occupying the strategic island city of Chalcis in Euboea as a forward base for his campaign. This move, which included his marriage to the daughter of the local dynast, aimed to consolidate Seleucid influence in central Greece but alarmed Roman allies and prompted urgent reinforcements under consul Manius Acilius Glabrio, who arrived with an army of approximately 20,000 infantry, 2,000 cavalry, and 15 elephants to counter the threat.[12][13] The occupation of Chalcis exacerbated diplomatic tensions, leading to a council at Demetrias where Hannibal, serving as Antiochus's advisor, urged a bold strategy of invading Italy to divert Roman forces, but the king opted instead for local consolidation, ignoring the counsel and focusing on Greek alliances.[14] Peace talks in 191 BC further highlighted the breakdown, as Roman envoys at Aegium delivered an ultimatum demanding Antiochus withdraw all forces from Greece below the passes of Thermopylae; the king rejected the terms, viewing them as infringing on his autonomy and the Aetolian alliance, thus escalating the conflict toward open war.[15] Diplomatic maneuvers intensified with Pergamon's King Eumenes II decisively aligning with Rome, providing critical naval support and intelligence against Antiochus, a shift motivated by territorial rivalries in Asia Minor and fears of Seleucid expansion. Rhodes, seeking to preserve regional stability, attempted mediation by sending embassies to both sides advocating for Greek autonomy and negotiated withdrawal, but these efforts failed amid Roman insistence on unconditional Seleucid retreat and Antiochus's refusal to yield.[16] The naval dimension culminated in the Battle of Myonessus in September 190 BC, where a combined Roman-Rhodian fleet of about 80 ships (58 Roman and 22 Rhodian) under Lucius Aemilius Regillus decisively defeated the Seleucid navy of 89 vessels commanded by Polyxenidas off the coast near Teos. Despite the numerical disadvantage, Roman boarding tactics and Rhodian maneuvers—the latter known for skilled seamanship and crucial in countering the heavier Seleucid "fives" and "tens" on the flank—overwhelmed the enemy, sinking 29 and capturing 13 ships (total 42 lost) while the Romans lost 2 sunk and 1 captured, thereby securing Roman dominance in the Aegean and enabling the safe transport of reinforcements to Asia Minor.[17][16]Roman Invasion of Asia Minor

Following the Roman victory at the Battle of Thermopylae in 191 BC, where consul Manius Acilius Glabrio defeated the forces of King Antiochus III, the Romans pursued the retreating Seleucid army out of Greece and toward the Hellespont.[18] This success compelled Antiochus to withdraw his troops across the strait into Asia Minor, abandoning his ambitions in Europe.[18] In late 190 BC, the Romans, under consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus, crossed the Hellespont into Asia Minor, facilitated by the recent Roman naval victory at Myonnesus that secured the Aegean approaches.[18] The consular army, totaling around 13,000 infantry and 500 cavalry, was joined by his brother, Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, who served as advisor, with the combined force linking up near Elaea.[18] The Romans linked up with the allied forces of King Eumenes II of Pergamum at the Caicus River, where Eumenes provided crucial logistical support, including troops and a fleet, before the combined army wintered at Pergamum.[18] (John D. Grainger, The Roman War of Antiochus the Great, Brill, 2002, pp. 104-108.) As the Roman campaign progressed, Scipio's forces swiftly captured several key coastal cities, including Ilion (ancient Troy), Abydos, and Adramyttium, which surrendered or fell after brief sieges, bolstering Roman supply lines and weakening Seleucid control in the Troad region.[18] In response, Antiochus employed scorched-earth tactics, ravaging areas like Elaea and Pergamum to deny resources to the invaders and retreating inland to consolidate his position.[18] (Grainger, The Roman War of Antiochus the Great, pp. 112-115.) Scipio then initiated a strategic march southward toward Sardis, the Seleucid regional capital in Lydia, aiming to draw Antiochus into a decisive engagement.[18] Prompted by this advance, Antiochus moved his army from Apamea eastward, positioning it to intercept the Romans near Magnesia ad Sipylum, setting the stage for the climactic confrontation.[18] (Grainger, The Roman War of Antiochus the Great, pp. 120-124.)Opposing Forces

Roman and Allied Army

The Roman and allied army assembled for the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BC totaled around 30,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry, drawn primarily from the Roman Republic's manipular legions and supporting contingents from Italian allies and Hellenistic kingdoms.[19][20] This force reflected the Roman military's evolution following the Macedonian Wars, emphasizing modular maniples that allowed greater flexibility on varied terrain compared to rigid Hellenistic formations.[21] The core of the army comprised two Roman legions, each approximately 5,400 strong, organized in the traditional triple line of hastati (younger spearmen in the front), principes (experienced swordsmen in the middle), and triarii (veteran spearmen in reserve).[20] Flanking these were equivalent allied Italian cohorts, totaling about 10,000 heavy infantry in similar manipular structure, providing balanced support and depth to the line.[19] Light-armed contingents bolstered the flanks, including 3,000 peltasts from the Achaean League skilled in skirmishing and 3,000 Cretan archers and slingers for ranged harassment, particularly effective against enemy elephants through volleys of javelins and firebrands.[20] The cavalry wing numbered around 3,000, with Roman and Italian horsemen forming the core, augmented by 800 elite Pergamene cataphracts and additional light cavalry suited for pursuit and flanking maneuvers.[19] In reserve stood 16 African war elephants, acquired from Numidian allies, though their smaller size limited their offensive role and they were positioned to counter Seleucid beasts if needed.[20] Command of the army fell to the consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus, an inexperienced but resolute leader who deferred to strategic advice from his brother, Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, serving as legate after his triumphs in the Second Punic War.[22] Eumenes II, king of Pergamon and a key Roman ally, held authority over the left-wing cavalry and light troops, leveraging his local knowledge and 3,000-strong contingent of mixed cavalry and infantry to enhance the Roman line's mobility.[23] Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus commanded the right wing, ensuring coordinated responses across the formation.[19] This structure highlighted the Roman army's strength in adaptability, with allied contributions providing specialized troops that complemented the legions' disciplined close-order fighting.[21]Seleucid Army

The Seleucid army assembled for the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BCE represented a vast, multinational force drawn from across the empire, reflecting Antiochus III's extensive reconquests in the East. Ancient historians Polybius and Livy estimated its total strength at approximately 72,000 troops, encompassing heavy infantry, cavalry, light auxiliaries, and war elephants, though modern scholars adjust this figure downward to around 50,000-60,000 based on logistical constraints and detailed unit breakdowns.[24][25] This composition highlighted the Hellenistic core augmented by eastern levies, including roughly 16,000 phalangites equipped with sarissas forming the main battle line, alongside diverse cavalry and skirmishers.[24] The army's structure centered on a Macedonian-style phalanx of 16,000 men in the van, arrayed in 32-deep files and divided into ten subgroups separated by war elephants, with an additional elite guard of argyraspides (silver-shields) positioned nearby. Flanking this were heterogeneous wings: the right under Zeuxis featured 3,000 cataphract heavy cavalry, 1,200 Dahae horse archers, Thessalian and Median contingents, 2,500 Mysian archers, and 4,000 Elymaean and Cyrtaean slingers and bowmen, supported by 16 elephants. The left wing, commanded by Antiochus's son Seleucus IV, included 15 Galatian scythed chariots, 2,000 Cappadocian cavalry from King Ariarathes, 3,000 mailed horsemen, Arabian dromedary archers, and light infantry such as 1,500 Cretans, 1,500 Carians and Cilicians, and 3,000 Trallians, Pisidians, Pamphylians, and Lycians, with another 16 elephants in reserve. Overall, the force incorporated 54-57 war elephants, each carrying towers with armed crews, alongside Agrianians serving as elite peltasts for skirmishing.[24][25] Antiochus III held overall command, personally leading the right wing to exploit his cavalry superiority, while his son Seleucus IV oversaw the left and Antipater directed the chariots and dromedaries there. Zeuxis managed the right-center coordination, with subordinates like Minnio and Philip handling the phalanx and elephants, respectively. This hierarchical structure aimed to integrate the empire's vassal contributions but often strained under the weight of cultural and tactical differences.[24] Despite its numerical advantages, the army suffered from inherent vulnerabilities, including poor coordination among its ethnically diverse units—ranging from Macedonian settlers to eastern nomads—which hindered unified maneuvers, and an over-reliance on elephants that proved unreliable when panicked by missile fire or terrain. These structural weaknesses, rooted in the challenges of commanding a far-flung imperial host, contributed to the force's ultimate disarray.[25]The Battle

Deployment and Terrain

The Battle of Magnesia occurred near the ancient city of Magnesia ad Sipylum in Lydia, Asia Minor (modern Manisa, Turkey), on an open plain bordered by Mount Sipylus to the east and the Hermus River (modern Gediz) to the west.[26] The engagement took place in winter 190/189 BC, during damp and misty conditions that affected visibility and mobility across the battlefield.[27] The terrain featured relatively flat, open fields suitable for cavalry maneuvers, but included marshy or waterlogged areas, particularly along the edges near the rivers, which limited the effectiveness of certain formations and units.[28] The Roman and allied forces, totaling around 30,000 men under the command of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus, deployed with their left flank anchored against the Hermus River to protect against envelopment. The core of the army consisted of four legions arranged in the traditional triplex acies formation—maniples of hastati in front, principes in the middle, and triarii in reserve—flanked by Italian allied infantry, with light troops and slingers interspersed. On the left wing, King Eumenes II of Pergamum positioned his cavalry and light infantry, including Achaean peltasts, to counter the expected Seleucid threat. The right wing featured a mix of Roman and allied cavalry, archers, slingers, and a small number of elephants held in reserve behind the main line, under the command of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. This compact deployment emphasized defensive cohesion and leveraged the river for flank security.[19] Opposing them, Antiochus III's Seleucid army, numbering approximately 70,000 and including a total of 54 elephants, formed an extended line designed to envelop the Romans through superior numbers in cavalry and elephants. The center was dominated by a Macedonian-style phalanx of 16,000 sarissaphoroi pikemen, arrayed in ten sections of 1,600 men each (50 files wide and 32 ranks deep), with 22 elephants positioned in the intervals between sections to guard against flanking attacks. In front of the phalanx were 57 scythed chariots intended to disrupt the Roman lines. The left wing, under crown prince Seleucus IV, comprised about 15,000 cavalry, including heavy cataphracts, Thessalians, Galatians, and light horse, supported by 10,000 light infantry, archers, and slingers, with the remaining elephants interspersed. The right wing, led personally by Antiochus, included 6,000 mixed cavalry (cataphracts, companions, and Galatian horsemen) along with additional light troops. This broad formation aimed to overlap the Roman lines, but the marshy ground on the Seleucid left hampered chariot mobility and cohesion from the outset, while the open plain favored the extensive cavalry wings.[19][21]Combat Phases and Tactics

The battle commenced with the advance of Antiochus III's scythed chariots against the Roman left wing, intended to sow chaos in the ranks through their slashing blades and speed. However, Eumenes II of Pergamon, commanding the allied left, ordered his Cretan archers, slingers, Trallian and Cretan javelin-men, and light cavalry to assail the chariots with a barrage of missiles and shouts, targeting the horses to induce panic.[19] The horses, unaccustomed to such noise and projectiles, bolted uncontrollably, some veering into the Seleucid ranks and others fleeing the field entirely, rendering the chariots ineffective and neutralizing this opening threat.[29] With the chariots disrupted, Eumenes launched his cavalry against the exposed Seleucid left wing, comprising Galatians, Cappadocians, and other auxiliaries under Seleucus and Antipater. The Pergamene and Achaean horsemen quickly routed these forces, slaying many and driving the survivors in disorder toward their camp; however, Eumenes pursued too far, temporarily isolating his wing from the main Roman advance.[19] On the opposite flank, Antiochus personally led his elite cavalry— including cataphracts and mounted archers—against the Roman right, initially breaking through the opposing Achaeans and Italians under Appius Claudius and Publius Sulpicius, forcing them back toward the reserves.[29] Yet, as the Seleucid right pressed forward without support from the center, reinforcements from Marcus Aemilius and Attalus of Pergamon stabilized the line, compelling Antiochus to recall his cavalry to bolster the faltering phalanx.[30] In the central engagement, the Roman legions under Lucius Cornelius Scipio advanced against the Seleucid phalanx of 16,000 Macedonian pikemen, supported by elephants divided among its files and wings. The phalanx, advancing unsupported after the chariot failure and with its left wing routed, suffered harassment from Roman velites and light infantry who exploited gaps between files with javelins and arrows, disrupting cohesion before close contact.[19] The legions then closed with swords and pila, outmaneuvering the rigid sarissa-armed formation on the uneven terrain, while allied light troops used fire-arrows and javelins to provoke panic among the Seleucid elephants.[29] The rampaging Seleucid elephants trampled their own lines, creating disorder that allowed the Romans to envelop and shatter the phalanx from the flanks and rear.[30] The ensuing rout spread rapidly as the Seleucid center collapsed, with surviving phalangites and auxiliaries fleeing en masse toward their camp at Sardis. Antiochus, wounded in the melee, escaped with his recalled cavalry, while the Romans pursued vigorously but halted at nightfall, preventing a complete annihilation.[19] The entire engagement lasted approximately two to three hours, highlighting Roman tactical flexibility—employing skirmishers to erode enemy formations and coordinated cavalry to exploit breakthroughs—against the Seleucid reliance on shock elements that faltered under countermeasures.[29]Aftermath

Casualties and Immediate Results

The Battle of Magnesia inflicted devastating casualties on the Seleucid army, with the ancient historian Livy reporting 50,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry killed, alongside 1,500 captured and 15 elephants seized, while Roman and allied losses totaled 300 infantry, 24 cavalry, and 25 from Pergamene forces.[21] These high Seleucid losses stemmed in part from tactical failures, including the early rout of scythed chariots and the panic of war elephants that disrupted their own lines.[21] In the immediate aftermath, Roman forces captured the entire Seleucid camp, including royal baggage and treasure, before pursuing the routed enemy to Sardis and occupying the city, which compelled Antiochus III to open negotiations for surrender.[31] This swift exploitation solidified Roman dominance over key regions like Lydia and Ionia, preventing any Seleucid regrouping in western Asia Minor.[32] The Seleucid defeat triggered a rapid collapse in Asia Minor, as Antiochus retreated eastward to Syria, abandoning the heartland to Roman and allied control, while widespread desertions among eastern contingents—such as Indian and Median troops—further eroded loyalty to the empire.[31] Short-term consequences included a grand Roman triumph in 189 BC celebrating the victory, during which consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio earned the cognomen Asiaticus for his command.[33] Pergamene king Eumenes II received territorial expansions in Asia Minor as a reward for his alliance and contributions.[32]Treaty of Apamea

The negotiations for the peace settlement following the Roman victory at Magnesia were conducted in 188 BC at Apamea in Phrygia, near modern Afyonkarahisar, Turkey, where Roman commissioners, including Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus and the former consul Gnaeus Manlius Vulso, along with ten legates, dictated terms to representatives of Antiochus III, such as the satrap Zeuxis and the general Antipater.[16][34] The Roman Senate had preliminarily approved the broad outlines earlier that year, with the commissioners tasked to finalize and enforce the conditions, administering oaths to ensure compliance.[35] The treaty's key provisions imposed severe restrictions on the Seleucid Empire to prevent future threats to Roman interests in the eastern Mediterranean. Antiochus was required to evacuate all territories in Europe and Asia Minor west of the Taurus Mountains, extending to the Halys River, ceding control over these regions to Roman allies.[16][34] He agreed to pay an indemnity of 15,000 Euboean talents to Rome—500 talents immediately, 2,500 upon ratification, and the remainder in annual installments of 1,000 talents over 12 years—plus an additional 350 talents to Eumenes II of Pergamon over five years; the payments were to be made in silver, with equivalent provisions in wheat if needed.[16][35] The Seleucids were limited to a navy of only ten decked warships, each with no more than 30 oars, prohibited from operating west of the Calycadnus River and Sarpedonian promontory except for specific emergencies, and forced to surrender all larger vessels and war elephants.[16][34] Military forces were restricted to garrisons for internal security, with no recruitment of mercenaries from Roman-allied territories, no harboring of Roman fugitives, and a ban on wars against islanders or in Europe; additionally, 20 noble hostages aged 18 to 40, including Antiochus's younger son, were to be sent to Rome, replaceable every three years except for the son.[16][35] Enforcement was overseen by the Roman commissioners through alliances with Pergamon and Rhodes, who received the ceded territories as rewards for their support. Eumenes II was granted Mysia, Lydia, Phrygia, and the Thracian Chersonese including Lysimachia, significantly expanding Pergamene influence, while Rhodes obtained the southwestern Anatolian coast, including Caria and Lycia, along with restored properties and exemptions from certain tributes.[34][35] The treaty was inscribed on bronze tablets deposited in Rome's Capitol, with Antiochus swearing to uphold it under Roman supervision to ensure the evacuation and payments proceeded without delay.[35] Antiochus III complied initially by dispatching the hostages and beginning payments, but the financial strain of the indemnity prompted him to launch a campaign in the eastern satrapy of Elymais in 187 BC to seize temple treasures for funds.[8] During this effort, he was killed by local inhabitants near Susa on July 3, 187 BC, an event that accelerated the Seleucid Empire's decline by disrupting further compliance and succession.[8]Legacy

Long-Term Geopolitical Effects

The Roman victory at the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BC, followed by the Treaty of Apamea, established a Roman protectorate over much of Asia Minor, fundamentally shifting the balance of power from Hellenistic kingdoms to Roman hegemony in the eastern Mediterranean. This arrangement positioned Rome as the arbiter of regional affairs without immediate direct annexation, relying instead on allied client states to maintain stability and extract tribute. Over the subsequent decades, this protectorate evolved into formal provincial control, culminating in the creation of the province of Asia after the Attalid Kingdom of Pergamon bequeathed its territories to Rome in 133 BC via the will of Attalus III; the ensuing revolt by Aristonicus was suppressed by 129 BC, solidifying Roman administrative presence and revenue streams from the wealthy Anatolian hinterlands.[36] The Seleucid Empire suffered profound and irreversible decline as a direct consequence of its territorial losses west of the Taurus Mountains, which deprived it of critical western revenues and military recruiting grounds essential for sustaining its vast domain. The massive indemnity of 15,000 talents imposed by the treaty exacerbated financial strain, fueling internal fragmentation through succession crises, regional revolts, and the erosion of central authority under subsequent rulers like Seleucus IV and Antiochus IV. This weakening facilitated the rise of the Parthian Empire in the east, where Arsacid leaders capitalized on Seleucid vulnerabilities during the power-transition crisis of the 160s–130s BC to expand from a peripheral satrapy into a formidable imperial rival, ultimately partitioning former Seleucid holdings in Mesopotamia and Iran. By 64 BC, the remnants of Seleucid Syria were annexed by the Roman general Pompey during his eastern campaigns, marking the complete dissolution of the empire and Rome's unchallenged dominance in the Levant.[37][38] Allied states reaped significant but temporary benefits from the redistribution of Seleucid lands, with the Kingdom of Pergamon under Eumenes II emerging as a primary beneficiary, acquiring vast territories that quintupled its size and enhanced its autonomy as a Roman client until its voluntary bequest to Rome in 133 BC. Similarly, Rhodes gained control over Lycia and Caria, bolstering its maritime trade and economic prosperity as a Roman collaborator in the Aegean. However, this expansion proved short-lived for Rhodes, as Roman suspicions of its ambitions—exacerbated by its support for Macedonia in the Third Macedonian War—led to direct intervention in 168 BC, curtailing its independence and foreshadowing further Roman encroachments.[39] The battle's outcome neutralized the last major Hellenistic threat to Roman interests in the east, allowing the Republic to redirect its military and diplomatic energies westward toward the Third Punic War (149–146 BC), which resulted in Carthage's destruction and the consolidation of Roman control over North Africa. This geopolitical realignment not only secured Rome's Mediterranean supremacy but also enabled internal political reforms, as the influx of eastern wealth and reduced external pressures intensified debates over land distribution and citizenship in the late Republic.[39]Modern Historiography and Assessments

The primary ancient sources for the Battle of Magnesia are the Greek historian Polybius, who drew on the eyewitness account of the Roman officer Pasion, and the Roman historians Livy in Books 37-38 of his Ab Urbe Condita and Appian in his Syrian Wars (chapters 30-36), both of whom relied heavily on Polybius. These accounts exhibit discrepancies, particularly in army sizes and casualties, with ancient figures often exaggerating Seleucid forces—such as claims of 72,000 infantry and 12,000 cavalry—to heighten dramatic effect and underscore Roman prowess.[40] Livy, for instance, reports 50,000 Seleucid dead against just 300 Roman losses, numbers modern scholars view as inflated for propagandistic purposes to glorify Roman efficiency.[23] Archaeological evidence from the site near modern Manisa, Turkey, remains limited, consisting primarily of inscriptions and coins that provide contextual details on Hellenistic military presence but no direct battle artifacts.[41] No major excavations have been reported post-2020, though ancient descriptions note marshy constraints along the Phrygius River, which restricted Seleucid maneuvers and contributed to their disarray. In modern scholarship, John D. Grainger's 2002 analysis in The Roman War of Antiochos the Great highlights the vulnerabilities of the Seleucid phalanx, arguing that its rigidity in uneven terrain and against mobile Roman legions marked a key tactical flaw in Hellenistic warfare.[42] Michael J. Taylor's 2013 biography Antiochus the Great emphasizes the pivotal role of Pergamene king Eumenes II, whose cavalry outflanked the Seleucid left and turned the battle, crediting allied coordination over Roman infantry alone. Ongoing debates include the precise date—late 190 BC versus early 189 BC—tied to Roman consular timelines and an interregnum period, as well as the realism of casualty figures, which scholars attribute to ancient Roman bias in inflating enemy losses to justify expansion.[43] Assessments of the battle position it as a turning point in infantry tactics, demonstrating the phalanx's limitations against adaptable legionary formations and eroding the notion of Hellenistic military superiority.[44] While no transformative updates have emerged since 2020, some historians advocate reevaluation through underutilized Seleucid eastern records, such as Babylonian chronicles, to cross-verify Roman-centric narratives and illuminate Antiochus III's broader strategic context.[3]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/From_the_Founding_of_the_City/Book_37

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/From_the_Founding_of_the_City/Book_38