Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Trumpet

View on Wikipedia

Trumpet in B♭ | |

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 423.233 (Valved aerophone sounded by lip vibration) |

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| flugelhorn, cornet, cornett, flumpet, bugle, natural trumpet, bass trumpet, post horn, Roman tuba, buccina, cornu, lituus, shofar, dord, dung chen, sringa, shankha, lur, didgeridoo, alphorn, Russian horns, serpent, ophicleide, piccolo trumpet, horn, alto horn, baritone horn, pocket trumpet, slide trumpet | |

| Part of a series on |

| Musical instruments |

|---|

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard B♭ or C trumpet.

Trumpet-like instruments have historically been used as signaling devices in battle or hunting, with examples dating back to the 2nd Millennium BC.[1] They began to be used as musical instruments only in the late 14th or early 15th century.[2] Trumpets are used in art music styles, appearing in orchestras, concert bands, chamber music groups, and jazz ensembles. They are also common in popular music and are generally included in school bands. Sound is produced by vibrating the lips in a mouthpiece,[3] which starts a standing wave in the air column of the instrument. Since the late 15th century, trumpets have primarily been constructed of brass tubing, usually bent twice into a rounded rectangular shape.

There are many distinct types of trumpet. The most common is a transposing instrument pitched in B♭ with a tubing length of about 1.48 m (4 ft 10 in). The cornet is similar to the trumpet but has a conical bore (the trumpet has a cylindrical bore) and its tubing is generally wound differently. Early trumpets did not provide means to change the length of tubing, whereas modern instruments generally have three (or sometimes four) valves in order to change their pitch. Most trumpets have valves of the piston type, while some have the rotary type. The use of rotary-valved trumpets is more common in orchestral settings (especially in German and German-style orchestras), although this practice varies by country. A musician who plays the trumpet is called a trumpet player or trumpeter.[4]

Etymology

[edit]

The English word trumpet was first used in the late 14th century.[5] The word came from Old French trompette, which is a diminutive of trompe.[5] The word trump, meaning trumpet, was first used in English in 1300. The word comes from Old French trompe 'long, tube-like musical wind instrument' (c. 1100s), cognate with Provençal tromba, Italian tromba, all probably from a Germanic source (compare Old High German trumpa, Old Norse trumba 'trumpet'), of imitative origin."[6]

History

[edit]

The earliest trumpets date back to 2000 BC and earlier. The bronze and silver Tutankhamun's trumpets from his grave in Egypt, bronze lurs from Scandinavia, and metal trumpets from China date back to this period.[7] Trumpets from the Oxus civilization (3rd millennium BC) of Central Asia have decorated swellings in the middle, yet are made out of one sheet of metal, which is considered a technical wonder for its time.[8]

The Salpinx was a straight trumpet 62 inches (1,600 mm) long, made of bone or bronze. Homer's Iliad (9th or 8th century BCE) contain the earliest reference to its sound and further, frequent descriptions are found throughout the Classical Period.[9] Salpinx contests were a part of the original Olympic Games.[10] The Shofar, made from a ram horn and the Hatzotzeroth, made of metal, are both mentioned in the Bible. They were said to have been played in Solomon's Temple around 3,000 years ago. They are still used on certain religious days.[10]

The Moche people of ancient Peru depicted trumpets in their art going back to AD 300.[11] The earliest trumpets were signaling instruments used for military or religious purposes, rather than music in the modern sense;[12] and the modern bugle continues this signaling tradition.

Improvements to instrument design and metal making in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance led to an increased usefulness of the trumpet as a musical instrument. The natural trumpets of this era consisted of a single coiled tube without valves and therefore could only produce the notes of a single overtone series. Changing keys required the player to change crooks of the instrument.[10] The development of the upper, "clarino" register by specialist trumpeters—notably Cesare Bendinelli—would lend itself well to the Baroque era, also known as the "Golden Age of the natural trumpet." During this period, a vast body of music was written for virtuoso trumpeters. The art was revived in the mid-20th century and natural trumpet playing is again a thriving art around the world. Many modern players in Germany and the UK who perform Baroque music use a version of the natural trumpet fitted with three or four vent holes to aid in correcting out-of-tune notes in the harmonic series.[13]

The melody-dominated homophony of the classical and romantic periods relegated the trumpet to a secondary role by most major composers owing to the limitations of the natural trumpet. Berlioz wrote in 1844:

Notwithstanding the real loftiness and distinguished nature of its quality of tone, there are few instruments that have been more degraded (than the trumpet). Down to Beethoven and Weber, every composer – not excepting Mozart – persisted in confining it to the unworthy function of filling up, or in causing it to sound two or three commonplace rhythmical formulae.[14]

Construction

[edit]

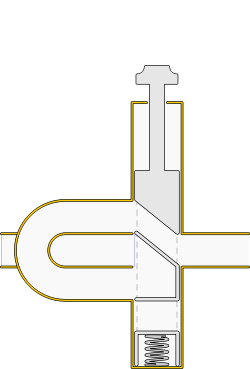

The trumpet is constructed of brass tubing bent twice into a rounded oblong shape.[15] As with all brass instruments, sound is produced by blowing air through slightly separated lips, producing a "buzzing" sound into the mouthpiece and starting a standing wave vibration in the air column inside the trumpet. The player can select the pitch from a range of overtones or harmonics by changing the lip aperture and tension (known as the embouchure).

The mouthpiece has a circular rim, which provides a comfortable environment for the lips' vibration. Directly behind the rim is the cup, which channels the air into a much smaller opening (the back bore or shank) that tapers out slightly to match the diameter of the trumpet's lead pipe. The dimensions of these parts of the mouthpiece affect the timbre or quality of sound, the ease of playability, and player comfort. Generally, the wider and deeper the cup, the darker the sound and timbre.

Modern trumpets have three (or, infrequently, four) piston valves, each of which increases the length of tubing when engaged, thereby lowering the pitch. The first valve lowers the instrument's pitch by a whole step (two semitones), the second valve by a half step (one semitone), and the third valve by one and a half steps (three semitones). Having three valves provides eight possible valve combinations (including "none"), but only seven different tubing lengths, because the third valve alone gives essentially the same tubing length as the 1–2 combination. (In practice there is often a deliberately designed slight difference between "1–2" and "3", and in that case trumpet players will select the alternative that gives the best tuning for the particular note being played.) When a fourth valve is present, as with some piccolo trumpets, it usually lowers the pitch a perfect fourth (five semitones). Used singly and in combination these valves make the instrument fully chromatic, i.e., able to play all twelve pitches of classical music. For more information about the different types of valves, see Brass instrument valves.

The overall pitch of the trumpet can be raised or lowered by the use of the tuning slide. Pulling the slide out lowers the pitch; pushing the slide in raises it. Pitch can be "bent" using the embouchure only.[16]

To overcome the problems of intonation and reduce the use of the slides, Renold Schilke designed the tuning-bell trumpet. Removing the usual brace between the bell and a valve body allows the use of a sliding bell; the player may then tune the horn with the bell while leaving the slide pushed in, or nearly so, thereby improving intonation and overall response.[17]

A trumpet becomes a closed tube when the player presses it to the lips; therefore, the instrument only naturally produces every other overtone of the harmonic series. The shape of the bell makes the missing overtones audible.[18] Most notes in the series are slightly out of tune and modern trumpets have slide mechanisms for the first and third valves with which the player can compensate by throwing (extending) or retracting one or both slides, using the left thumb and ring finger for the first and third valve slides respectively.

Trumpets can be constructed from other materials, including plastic.[19]

Types

[edit]

The most common type is the B♭ trumpet, but A, C, D, E♭, E, low F, and G trumpets are also available. The C trumpet is most common in American orchestral playing, where it is used alongside the B♭ trumpet. Orchestral trumpet players are adept at transposing music at sight, frequently playing music written for the A, B♭, D, E♭, E or F trumpet as well as for the B, C♯, F♯ or G trumpet (which is used more rarely) on the C trumpet or B♭ trumpet.

The smallest trumpets are referred to as piccolo trumpets. The most common models are built to play in both B♭ and A, with separate leadpipes for each key. The tubing in the B♭ piccolo trumpet is one-half the length of that in a standard B♭ trumpet making it sound an octave higher. Piccolo trumpets in G, F and C are also manufactured, but are less common. Almost all piccolo trumpets have four valves instead of three—the fourth valve usually lowers the pitch by a fourth, making some lower notes accessible and creating alternate fingerings for certain trills. Maurice André, Håkan Hardenberger, David Mason, and Wynton Marsalis are some well-known trumpet players known for their virtuosity on the piccolo trumpet.

Trumpets pitched in the key of low G are also called sopranos, or soprano bugles, after their adaptation from military bugles. Traditionally used in drum and bugle corps, sopranos employ either rotary valves or piston valves.

The bass trumpet is at the same pitch as a trombone and is usually played by a trombone player,[4] although its music is written in treble clef. Most bass trumpets are pitched in either C or B♭. The C bass trumpet sounds an octave lower than written, and the B♭ bass sounds a major ninth (B♭) lower, making them both transposing instruments.

The historical slide trumpet was probably first developed in the late 14th century for use in alta cappella wind bands. Deriving from early straight trumpets, the Renaissance slide trumpet was essentially a natural trumpet with a sliding leadpipe. This single slide was awkward, as the entire instrument moved, and the range of the slide was probably no more than a major third. Originals were probably pitched in D, to fit with shawms in D and G, probably at a typical pitch standard near A=466 Hz. No known instruments from this period survive, so the details—and even the existence—of a Renaissance slide trumpet is a matter of debate among scholars. While there is documentation (written and artistic) of its existence, there is also conjecture that its slide would have been impractical. Some slide trumpet designs saw use in England in the 18th century.[20]

The pocket trumpet is a compact B♭ trumpet. The bell is usually smaller than a standard trumpet bell and the tubing is more tightly wound to reduce the instrument size without reducing the total tube length. Its design is not standardized, and the quality of various models varies greatly. It can have a unique warm sound and voice-like articulation. Since many pocket trumpet models suffer from poor design as well as poor manufacturing, the intonation, tone color and dynamic range of such instruments are severely hindered. Professional-standard instruments are, however, available. While they are not a substitute for the full-sized instrument, they can be useful in certain contexts. The jazz musician Don Cherry was renowned for his playing of the pocket instrument.

The tubing of the bell section of a herald trumpet is straight, making it long enough to accommodate a hanging banner. This instrument is mostly used for ceremonial events such as parades and fanfares.

David Monette designed the flumpet in 1989 for jazz musician Art Farmer. It is a hybrid of a trumpet and a flugelhorn, pitched in B♭ and using three piston valves.[21]

Other variations include rotary-valve, or German, trumpets (which are commonly used in professional German and Austrian orchestras), alto and Baroque trumpets, and the Vienna valve trumpet (primarily used in Viennese brass ensembles and orchestras such as the Vienna Philharmonic and Mnozil Brass).

The trumpet is often confused with its close relative the cornet, which has a more conical tubing shape compared to the trumpet's more cylindrical tube. This, along with additional bends in the cornet's tubing, gives the cornet a slightly mellower tone, but the instruments are otherwise nearly identical. They have the same length of tubing and, therefore, the same pitch, so music written for one of them is playable on the other. Another relative, the flugelhorn, has tubing that is even more conical than that of the cornet, and an even mellower tone. It is sometimes supplied with a fourth valve to improve the intonation of some lower notes.

Playing

[edit]Fingering

[edit]On any modern trumpet, cornet, or flugelhorn, pressing the valves indicated by the numbers below produces the written notes shown. "Open" means all valves up, "1" means first valve, "1–2" means first and second valve simultaneously, and so on. The sounding pitch depends on the transposition of the instrument. Engaging the fourth valve, if present, usually drops any of these pitches by a perfect fourth as well. Within each overtone series, the different pitches are attained by changing the embouchure.

Each overtone series on the trumpet begins with the first overtone—the fundamental of each overtone series cannot be produced except as a pedal tone. Notes in parentheses are the sixth overtone, representing a pitch with a frequency of seven times that of the fundamental; while this pitch is close to the note shown, it is flat relative to equal temperament, and use of those fingerings is generally avoided.

The fingering schema arises from the length of each valve's tubing (a longer tube produces a lower pitch). Valve "1" increases the tubing length enough to lower the pitch by one whole step, valve "2" by one half step, and valve "3" by one and a half steps.[22] This scheme and the nature of the overtone series create the possibility of alternate fingerings for certain notes. For example, third-space "C" can be produced with no valves engaged (standard fingering) or with valves 2–3. Also, any note produced with 1–2 as its standard fingering can also be produced with valve 3 – each drops the pitch by 1+1⁄2 steps. Alternate fingerings may be used to improve facility in certain passages, or to aid in intonation. Extending the third valve slide when using the fingerings 1–3 or 1-2-3 further lowers the pitch slightly to improve intonation.[23]

Some of the partials of the harmonic series that a modern B♭ trumpet can play for each combination of valves pressed are in tune with 12-tone equal temperament and some are not.[24]

Mutes

[edit]

Various types of mutes can be placed in or over the bell, which decreases volume and changes timbre.[25] Trumpets have a wide selection of mutes: common ones include the straight mute, cup mute, harmon mute (wah-wah or wow-wow mute, among other names[26]), plunger, bucket mute, and practice mute.[27] A straight mute is generally used when the type of mute is not specified.[26] Jazz and commercial music call for a wider range of mutes than most classical music[25] and many mutes were invented for jazz orchestrators.[28]

Mutes can be made of many materials, including fiberglass, plastic, cardboard, metal, and "stone lining", a trade name of the Humes & Berg company.[29] They are often held in place with cork.[25][30] To better keep the mute in place, players sometimes dampen the cork by blowing warm, moist air on it.[25]

The straight mute is conical and constructed of either metal (usually aluminum[26])—which produces a bright, piercing sound—or another material, which produces a darker, stuffier sound.[31][32] The cup mute is shaped like a straight mute with an additional, bell-facing cup at the end, and produces a darker tone than a straight mute.[33] The harmon mute is made of metal (usually aluminum or copper[26]) and consists of a "stem" inserted into a large chamber.[33] The stem can be extended or removed to produce different timbres, and waving one's hand in front of the mute produces a "wah-wah" sound, hence the mute's colloquial name.[33]

Range

[edit]Using standard technique, the lowest note is the written F♯ below middle C.[citation needed] There is no actual limit to how high brass instruments can play, but fingering charts generally go up to the high C two octaves above middle C. Several trumpeters have achieved fame for their proficiency in the extreme high register, among them Maynard Ferguson, Cat Anderson, Dizzy Gillespie, Doc Severinsen, John Madrid, and more recently Wayne Bergeron, Louis Dowdeswell, Thomas Gansch, James Morrison, Jon Faddis and Arturo Sandoval. It is also possible to produce pedal tones below the low F♯, which is a device occasionally employed in the contemporary repertoire for the instrument.

Extended technique

[edit]Contemporary music for the trumpet makes wide uses of extended trumpet techniques.

Flutter tonguing: The trumpeter rolls the tip of the tongue (as if rolling an "R" in Spanish) to produce a 'growling like' tone. This technique is widely employed by composers like Berio and Stockhausen.

Growling: Simultaneously playing tone and using the back of the tongue to vibrate the uvula, creating a distinct sound. Most trumpet players will use a plunger with this technique to achieve a particular sound heard in a lot of Chicago Jazz of the 1950s.

Double tonguing: The player articulates using the syllables ta-ka ta-ka ta-ka.

Triple tonguing: The same as double tonguing, but with the syllables ta-ta-ka ta-ta-ka ta-ta-ka.

Doodle tongue: The trumpeter tongues as if saying the word doodle. This is a very faint tonguing similar in sound to a valve tremolo.

Glissando: Trumpeters can slide between notes by depressing the valves halfway and changing the lip tension. Modern repertoire makes extensive use of this technique.

Vibrato: It is often regulated in contemporary repertoire through specific notation. Composers can call for everything from fast, slow or no vibrato to actual rhythmic patterns played with vibrato.

Pedal tone: Composers have written notes as low as two-and-a-half octaves below the low F♯ at the bottom of the standard range. Extreme low pedals are produced by slipping the lower lip out of the mouthpiece. Claude Gordon assigned pedals as part of his trumpet practice routines, that were a systematic expansion on his lessons with Herbert L. Clarke. The technique was pioneered by Bohumir Kryl.[34]

Microtones: Composers such as Scelsi and Stockhausen have made wide use of the trumpet's ability to play microtonally. Some instruments feature a fourth valve that provides a quarter-tone step between each note. The jazz musician Ibrahim Maalouf uses such a trumpet, invented by his father to make it possible to play Arab maqams.

Valve tremolo: Many notes on the trumpet can be played in several different valve combinations. By alternating between valve combinations on the same note, a tremolo effect can be created. Berio makes extended use of this technique in his Sequenza X.

Noises: By hissing, clicking, or breathing through the instrument, the trumpet can be made to resonate in ways that do not sound at all like a trumpet. Noises may require amplification.

Preparation: Composers have called for trumpeters to play under water, or with certain slides removed. It is increasingly common for composers to specify all sorts of preparations for trumpet. Extreme preparations involve alternate constructions, such as double bells and extra valves.

Split tone: Trumpeters can produce more than one tone simultaneously by vibrating the two lips at different speeds. The interval produced is usually an octave or a fifth.

Lip-trill or shake: Also known as "lip-slurs". By rapidly varying air speed, but not changing the depressed valves, the pitch can vary quickly between adjacent harmonic partials. Shakes and lip-trills can vary in speed, and in the distance between the partials. However, lip-trills and shakes usually involve the next partial up from the written note.

Multi-phonics: Playing a note and "humming" a different note simultaneously. For example, sustaining a middle C and humming a major 3rd "E" at the same time.

Circular breathing: A technique wind players use to produce uninterrupted tone, without pauses for breaths. The player puffs up the cheeks, storing air, then breathes in rapidly through the nose while using the cheeks to continue pushing air outwards.

Instruction and method books

[edit]One trumpet method is Jean-Baptiste Arban's Complete Conservatory Method for Trumpet (Cornet).[35] Other well-known method books include Technical Studies by Herbert L. Clarke,[36] Grand Method by Louis Saint-Jacome, Daily Drills and Technical Studies by Max Schlossberg, and methods by Ernest S. Williams, Claude Gordon, Charles Colin, James Stamp, and Louis Davidson.[37] A common method book for beginners is the Walter Beeler's Method for the Cornet, and there have been several instruction books written by virtuoso Allen Vizzutti.[38] Merri Franquin wrote a Complete Method for Modern Trumpet,[39] which fell into obscurity for much of the twentieth century until public endorsements by Maurice André revived interest in this work.[40]

Players

[edit]

In early jazz, Louis Armstrong was well known for his virtuosity and his improvisations on the Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings, and his switch from cornet to trumpet is often cited as heralding the trumpet's dominance over the cornet in jazz.[4][41] Dizzy Gillespie was a gifted improviser with an extremely high (but musical) range, building on the style of Roy Eldridge but adding new layers of harmonic complexity. Gillespie had an enormous impact on virtually every subsequent trumpeter, both by the example of his playing and as a mentor to younger musicians. Miles Davis is widely considered one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century—his style was distinctive and widely imitated. Davis' phrasing and sense of space in his solos have been models for generations of jazz musicians.[42] Cat Anderson was a trumpet player who was known for the ability to play extremely high with an even more extreme volume, who played with Duke Ellington's Big Band. Maynard Ferguson came to prominence playing in Stan Kenton's orchestra, before forming his own band in 1957. He was noted for being able to play accurately in a remarkably high register.[43]

Repertoire

[edit]Solos

[edit]In the 1790s Anton Weidinger developed the first successful keyed trumpet, capable of playing chromatically. Joseph Haydn's Trumpet Concerto was written for him in 1796 and startled contemporary audiences by its novelty,[44] a fact shown off by some stepwise melodies played low in the instrument's range.

In art

[edit]-

The Last Judgment (Bosch, Bruges), c. 1500–1510

-

Trumpet-Player in front of a Banquet, Gerrit Dou, c. 1660–1665

-

Illustration for The Trumpeter Taken Prisoner from an 1887 children's edition of Aesop's Fables

-

Louis Armstrong statue in Algiers, New Orleans

-

Miles Davis statue in Kielce, Poland

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ White, H.N. (25 June 2023). "History of the Trumpet and Cornet". Trumpet-history.com. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ "History of the Trumpet (According to the New Harvard Dictionary of Music)". petrouska.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ "Brass Family of Instruments: What instruments are in the Brass Family?". www.orsymphony.org. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Koehler 2013

- ^ a b "Trumpet". www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ "Trump". www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ Edward Tarr, The Trumpet (Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1988), 20–30.

- ^ "Trumpet with a swelling decorated with a human head," Musée du Louvre

- ^ Homer, Iliad, 18. 219.

- ^ a b c "History of the Trumpet | Pops' Trumpet College". Bbtrumpet.com. 8 November 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ^ "Chicago Symphony Orchestra – Glossary – Brass instruments". cso.org. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- ^ John Wallace and Alexander McGrattan, The Trumpet, Yale Musical Instrument Series (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011): 239. ISBN 978-0-300-11230-6.

- ^ Berlioz, Hector (1844). Treatise on modern Instrumentation and Orchestration. Edwin F. Kalmus, NY, 1948.

- ^ "Trumpet, Brass Instrument". dsokids.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- ^ Blackwell, James (11 December 2012). "Pitch Bends!". Blackwells Trumpet Basics. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Bloch, Dr. Colin (August 1978). "The Bell-Tuned Trumpet". Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ D. J. Blaikley, "How a Trumpet Is Made. I. The Natural Trumpet and Horn", The Musical Times, 1 January 1910, p. 15.

- ^ P-trumpet

- ^ Lessen, Martin (1997). "JSTOR: Notes, Second Series". Notes. 54 (2): 484–485. doi:10.2307/899543. ISSN 0027-4380. JSTOR 899543.

- ^ Koehler, Elisa (2014). Fanfares and Finesse: A Performer's Guide to Trumpet History and Literature. Indiana University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-253-01179-4. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Pagliaro, Michael J. (2016). The Brass Instrument Owner's Handbook. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-1-4422-6862-3. OCLC 946032345.

- ^ Ely, Mark C.; Van Deuren, Amy E. (2009). Wind Talk for Brass: A Practical Guide to Understanding and Teaching Brass Instruments. Amy E. Van Deuren. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 8–12. ISBN 978-0-19-971631-9. OCLC 472461178.

- ^ Schafer, Erika. "Trumpet Tuning Tendencies Relating to the Overtone Series with Solutions". UTC Trumpet Studio. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d Ely 2009, p. 109.

- ^ a b c d Ely 2009, p. 111.

- ^ For the "widest selection of mutes", see Sevsay 2013, p. 125. *For a list of common mutes, see Ely 2009, p. 109.

- ^ Boyden, David D.; Bevan, Clifford; Page, Janet K. (20 January 2001). "Mute". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.19478. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ For the list of materials, see Ely 2009, p. 109.

- For the origin of "stonelined mutes", see Koehler 2013, p. 173.

- ^ Sevsay 2013, p. 125.

- ^ Sevsay 2013, p. 125: "plastic (fiberglass): not as forceful as the metal mute, a bit darker in color, but still penetrating"

- ^ Koehler 2013, p. 173.

- ^ a b c Sevsay 2013, p. 126.

- ^ Joseph Wheeler, "Review: Edward H. Tarr, Die Trompete" The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 31, May 1978, p. 167.

- ^ Arban, Jean-Baptiste (1894, 1936, 1982). Arban's Complete Conservatory Method for trumpet. Carl Fischer, Inc. ISBN 0-8258-0385-3.

- ^ Herbert L. Clarke (1984). Technical Studies for the Cornet, C. Carl Fischer, Inc. ISBN 0-8258-0158-3.

- ^ Colin, Charles and Advanced Lip Flexibilities.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Allen Vizzutti Official Website". www.vizzutti.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ Franquin, Merri (2016) [1908]. Quinlan, Timothy (ed.). "Complete Method for Modern Trumpet". qpress.ca. Translated by Jackson, Susie.

- ^ Shamu, Geoffrey. "Merri Franquin and His Contribution to the Art of Trumpet Playing" (PDF). p. 20. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ West, Michael J. (3 November 2017). "The Cornet: Secrets of the Little Big Horn". JazzTimes.com. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Miles Davis, Trumpeter, Dies; Jazz Genius, 65, Defined Cool". nytimes.com. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- ^ "Ferguson, Maynard". Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- ^ Keith Anderson, liner notes for Naxos CD 8.550243, Famous Trumpet Concertos, "Haydn's concerto, written for Weidinger in 1796, must have . At the first performance of the new concerto in Vienna in 1800 a trumpet melody was heard in a lower register than had hitherto been practicable."

Bibliography

[edit]- Barclay, R. L. (1992). The art of the trumpet-maker: the materials, tools, and techniques of the seventeenth [sic] and eighteenth centuries in Nuremberg. Oxford [England]: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-816223-5.

- Bate, Philip (1978). The trumpet and trombone : an outline of their history, development, and construction (2nd ed.). London: E. Benn. ISBN 0-393-02129-7.

- Brownlow, James Arthur (1996). The last trumpet: a history of the English slide trumpet. Stuyvesant, N.Y.: Pendragon Press. ISBN 0-945193-81-5.

- Campos, Frank Gabriel (2005). Trumpet technique. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516692-2.

- Cassone, Gabriele (2009). The trumpet book (1st ed.). Varese, Italy: Zecchini. ISBN 978-88-87203-80-6.

- Ely, Mark C. (2009). Wind talk for brass: a practical guide to understanding and teaching brass instruments. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532924-7.

- English, Betty Lou (1980). You can't be timid with a trumpet: notes from the orchestra (1st ed.). New York: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Books. ISBN 0-688-41963-1.

- Koehler, Elisa (2013). Dictionary for the modern trumpet player. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8658-2.

- Sherman, Roger (1979). The trumpeter's handbook: a comprehensive guide to playing and teaching the trumpet. Athens, Ohio: Accura Music. ISBN 0-918194-02-4.

- Sevsay, Ertuğrul (2013). The Cambridge guide to orchestration. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-107-02516-5.

- Smithers, Don L. (1973). The music and history of the baroque trumpet before 1721 (1st ed.). Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2157-4.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of trumpet at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of trumpet at Wiktionary- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). 1911.

- International Trumpet Guild, international trumpet players' association with online library of scholarly journal back issues, news, jobs and other trumpet resources.

Trumpet

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Terminology

Origins of the Name

The word "trumpet" entered English in the late 14th century, derived from the Old French "trompette," a diminutive form of "trompe," which itself stems from a Germanic root, possibly Frankish *trumpa or Old High German "trumpa," imitative of the instrument's sound.[7] This term originally denoted a small wind instrument used for proclamation, summoning, or warning, reflecting its primary role as a signaling device in military and ceremonial contexts.[7] Etymologically, the trumpet's nomenclature connects to ancient wind instruments, particularly the Roman tuba, a straight military trumpet employed for signals in battles and rituals from around 500 BCE.[8] Although the Latin "tuba"—meaning "tube" and serving as the medieval Latin word for trumpet—did not directly influence the French-derived "trumpet," it established a conceptual lineage for straight-bored signaling horns that persisted into European terminology.[8] In medieval English, terminology shifted from terms like "clarion," borrowed from Old French "clarion" (from Latin "clarus," meaning "clear" or "loud," due to its piercing tone), which referred to a shrill, narrow-bored trumpet used in warfare, to the more general "trumpet" by the 15th century.[9] This evolution mirrored the instrument's broadening application beyond high-register military calls. Cross-cultural exchanges, notably during the Crusades (11th–13th centuries), introduced Arabic terms that shaped European nomenclature; for instance, the generic Arabic "al-būq" (meaning horn or trumpet) influenced words like "albogón" (a medieval Spanish trumpet) and contributed to "bugle" via interactions in the Iberian Peninsula and Levant.[10] These borrowings underscored the trumpet's enduring association with military signaling across cultures, as "al-būq" and related terms like "al-nafīr" denoted long, straight horns for commands in Islamic armies, paralleling European uses.[10]Modern Terminology

In modern trumpet terminology, the bore refers to the internal diameter of the instrument's tubing, which is predominantly cylindrical in contemporary designs to promote a focused, brilliant tone, with standard sizes ranging from 0.401 inches (XS) to 0.468 inches (XL); conical bores, such as step-bore variants, are less common and offer a warmer, more blended sound.[11] The bell is the flared terminus of the trumpet, the shape or taper of which influences projection and timbre; for example, a fast taper (e.g., Bach #72 profile) yields a darker, solid tone suited to symphonic playing, while a slow taper (e.g., Bach #25) produces a focused, direct sound.[11] The leadpipe is the initial segment of tubing extending from the mouthpiece receiver to the valve section or tuning slide, impacting airflow resistance and response; common types include the Bach #25 with a 0.345-inch venturi for balanced play, and the #43 for a brighter sound suited to jazz and commercial styles.[11] The mouthpiece shank denotes the tapered portion of the mouthpiece that inserts into the leadpipe, typically available in trumpet (longer, narrower) or cornet (shorter, wider) configurations to match instrument receivers and optimize seal and vibration transfer.[11] Other key terms include the valves, mechanisms (piston or rotary) that lengthen the tubing to change pitch, with three standard on most trumpets; the mouthpiece, comprising the cup (where lips buzz), rim (contact surface), and backbore (air channel); and the tuning slide, adjustable section for pitch correction.[4][1]History

Ancient and Medieval Periods

The earliest precursors to the trumpet were natural materials such as animal horns and conch shells, employed for signaling purposes in prehistoric societies. Animal horns, hollowed and shaped for blowing, served as acoustic signals for hunting, warnings, or communal gatherings across various ancient cultures, with evidence of their use dating back tens of thousands of years. Conch shells, modified by cutting the spire and sometimes adding a mouthpiece, produced resonant tones suitable for long-distance communication; a notable example is a large conch shell horn discovered in Marsoulas Cave in the French Pyrenees, dated to approximately 18,000 years ago, which yielded musical notes when tested with a modern mouthpiece. These instruments lacked metal construction but laid the foundation for later lip-reed aerophones through their emphasis on projection and signaling. During the Bronze Age, metalworking advancements enabled the creation of more durable horn-like instruments, particularly in Europe and the Near East. In Ireland, cast-bronze horns emerged as some of the region's oldest musical artifacts, primarily from the Middle and Late Bronze Age (c. 1500–500 BCE), crafted from copper alloyed with imported tin using clay molds. Examples include side-blown and end-blown horns from hoards like Dowris in County Offaly (c. 900–500 BCE), which produced deep, booming sounds likely intended for ceremonial or ritualistic signaling rather than melodic music. These Irish instruments, often found in groups, highlight a specialized tradition of bronze aerophones that required considerable skill to play and may have symbolized status or communal events. In ancient Egypt, trumpet-like instruments appeared concurrently with Bronze Age metallurgy, exemplified by the two trumpets discovered in the tomb of Tutankhamun (c. 1332–1323 BCE). One silver trumpet, approximately 58 cm long with intricate engravings of deities like Amun-Ra, and one bronze trumpet, about 50 cm long featuring the pharaoh's cartouches and floral motifs, were functional signaling devices used in royal processions, religious rituals, and possibly military contexts to assert divine authority. Both featured a straight, tubular design with a flared bell, producing pitches around B♭ and D on the bronze example, aligning with their role in clear, penetrating calls rather than complex harmony. These artifacts, housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, represent some of the earliest preserved metal trumpets, underscoring Egypt's influence on wind instrument development. The Roman tuba, a straight military signal instrument produced around 500 BCE, further exemplified the trumpet's evolution into a disciplined tool for organized societies. Constructed from copper or iron in a conical bore with a length of 120–140 cm, divided into three sections for assembly with a simple mouthpiece, the tuba was designed for maximum volume to direct troop movements, announce advances or retreats, and coordinate battles. Historical accounts, such as those involving Julius Caesar's use during campaigns, describe its piercing tone cutting through battlefield chaos, while it also featured in civilian roles like triumphal processions, sacrifices, and funerals. This straight form contrasted with curved variants but emphasized the trumpet's primary function as a non-melodic communicator in hierarchical structures. In the medieval period, trumpet designs diversified into straight or folded configurations, with instruments like the clarion and early slide instruments serving feudal signaling needs without mechanical aids for pitch alteration. The clarion, a high-pitched metal trumpet emerging around the 13th century, was favored for its shrill, far-carrying sound in military and civic announcements, often played by guild-organized trumpeters in cities like Florence, where ensembles of 6–8 performers broadcasted decrees or heralded noble arrivals. Early slide instruments such as the slide trumpet (trompette des menestrels) appeared around the 1420s, allowing limited diatonic adjustments through a sliding mechanism, while the sackbut (an early trombone) developed by around 1450 in folded forms for portability and was used in courtly or ecclesiastical settings to produce fanfares. These instruments played crucial roles in feudal hierarchies, such as signaling commands during hunts to coordinate riders and hounds, or in early ceremonies like coronations and tournaments to denote rank and authority, reinforcing social order through audible prestige. By the late Middle Ages, trumpet guilds in Europe regulated their exclusive use, limiting access to nobility and underscoring their symbolic power in non-musical contexts.Renaissance to Baroque Era

During the Renaissance, the trumpet transitioned from its straight form to a folded S-shape design by the early 15th century, allowing for greater portability and control while maintaining its role in ceremonial and military signaling.[12] This evolution occurred amid Europe's cultural revival, with Nuremberg emerging as a major center for brass instrument production by the 16th century.[12] Trumpeters were organized into exclusive guilds, such as the Imperial Guild of Trumpeters and Kettledrummers established in 1623 by Emperor Ferdinand II, which regulated training, limited membership, and preserved the instrument's prestige for royal courts and civic events.[12] These guilds ensured that trumpet playing remained a hereditary profession, often passed down through families like the Neuschels and Hainleins in Germany, where makers supplied instruments across Europe.[13] In the 16th century, advancements included the use of removable shanks and early crooks—interchangeable tubing sections—to adjust tuning for different keys, enabling the instrument to adapt to varying pitch standards without altering its core natural design.[14] This facilitated the trumpet's integration into polyphonic music, though it remained limited to the harmonic overtone series, producing only about eight usable notes in its fundamental register.[12] Virtuosi like Girolamo Fantini (c. 1600–1675), a prominent Italian trumpeter, advanced techniques by demonstrating the use of lipping—subtly adjusting embouchure to bend impure harmonics such as the 11th and 13th partials—allowing diatonic scales in the extreme high register (clarino style).[12] Fantini's 1638 treatise Modo per imparare a sonare di tromba included the first composed sonatas for trumpet and continuo, marking a shift toward soloistic art music and influencing Baroque performance practices.[12] The Baroque era saw the trumpet's prominence in opera, sacred works, and orchestral settings, despite its technical constraints. Claudio Monteverdi featured five natural trumpets, including clarino parts, in the opening Toccata of his 1607 opera L'Orfeo for fanfares and symbolic grandeur, exploiting the instrument's brilliant upper partials.[15] Henry Purcell incorporated natural trumpets in odes and anthems, such as The Yorkshire Feast Song (1694), to evoke majesty and ceremonial pomp.[12] Johann Sebastian Bach composed extensively for the natural trumpet, particularly for Leipzig Stadtpfeifer Gottfried Reiche, in cantatas like BWV 51 (Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen, 1730) and BWV 172 (Erschallet, ihr Lieder), requiring ranges from the third to eighteenth partials through skilled lipping to navigate chromatic demands.[12] As the Baroque waned in the late 18th century, innovations addressed the natural trumpet's limitations. Viennese court trumpeter Anton Weidinger developed the keyed trumpet around 1792, adding spring-loaded keys to vent holes for chromatic fingering, building on earlier prototypes to expand playability beyond overtones.[16] This instrument served as a crucial precursor to the valved trumpet, enabling composers like Joseph Haydn—whose 1796 Trumpet Concerto was premiered on it in 1800—to write more melodic lines, though it remained in use only until the 1820s.[16]Classical and Romantic Periods

The Classical period marked a transitional phase for the trumpet, bridging natural horn techniques from the Baroque era with emerging chromatic capabilities. Joseph Haydn composed his Trumpet Concerto in E-flat major (Hob. VIIe/1) in 1796 specifically for the keyed trumpet invented by Anton Weidinger around 1790, which added five spring-loaded keys to an E-flat natural trumpet, allowing for chromatic playing across a wider range than the traditional harmonic series.[17][18] This innovation enabled more melodic and soloistic roles for the instrument in orchestral settings, as evidenced by the concerto's demands for agile passages and lyrical expression previously limited on natural trumpets. By the early 19th century, the keyed trumpet facilitated a gradual shift toward standardized tunings in B-flat and C, with B-flat becoming prevalent for brighter, fanfare-like tones and C for more versatile orchestral integration, reflecting composers' needs for consistent pitch across ensemble parts.[19][14] The invention of valves revolutionized the trumpet during this period, enabling full chromaticism and greater agility. In 1835, Viennese instrument maker Joseph Riedl patented the rotary valve, an improvement on earlier designs that allowed efficient airflow redirection through rotating cylinders, which became a staple in German and Austrian brass instruments.[18] Complementing this, French maker François Périnet patented the modern piston valve in 1839, featuring staggered square ports for smoother, faster action compared to prior box valves, thus expanding the trumpet's technical possibilities in both solo and ensemble contexts.[18] These advancements supplanted the keyed trumpet by the 1840s, standardizing valved models in B-flat and C for classical orchestras and paving the way for Romantic-era demands. In the Romantic period, composers like Hector Berlioz, Richard Wagner, and Gustav Mahler expanded the trumpet's role, requiring extended range—often from pedal tones below the staff to high altissimo notes—and extreme dynamics to evoke dramatic intensity and emotional depth. Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique (1830) employed valved cornets alongside natural trumpets for vivid timbral contrasts and forceful accents, while Wagner's operas, such as Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), called for multiple trumpets in varied tunings to support leitmotifs with piercing fanfares and sustained power. Mahler's symphonies further pushed boundaries, scoring for high B-flat trumpets reaching above high C and low F extensions for brooding effects, integrating the instrument as a narrative voice in expansive orchestral textures.[20] Military bands exerted significant influence on trumpet design by the mid-19th century, driving the proliferation of compact, valved models suited for outdoor performance. The rise of brass bands in Europe and America, fueled by military traditions, favored piston-valved cornets and B-flat trumpets for their portability and projection, leading to specialized variants with upright bells and lighter construction by makers like Adolphe Sax.[21][22] This band-oriented evolution influenced orchestral trumpets, promoting durable, mass-produced designs that balanced military robustness with symphonic precision.20th Century and Modern Developments

The 20th century marked a transformative era for the trumpet, propelled by its integration into jazz, where it evolved from ensemble support to a vehicle for virtuosic improvisation. In the 1920s, Louis Armstrong emerged as a pioneering figure, revolutionizing trumpet technique through his bold phrasing, wide dynamic range, and scat-like solos, as heard in recordings like "West End Blues," which shifted jazz's emphasis from collective improvisation to individual expression.[23] This innovation laid the groundwork for subsequent styles, including bebop in the 1940s, where Dizzy Gillespie's high-register acrobatics and harmonic complexity, exemplified in tracks like "A Night in Tunisia," expanded the instrument's melodic and rhythmic possibilities.[24] By the 1960s and 1970s, Miles Davis further diversified the trumpet's role in jazz fusion, incorporating electric amplification and effects pedals such as the wah-wah to blend jazz with rock and funk, as on albums like Bitches Brew, creating a textured, electronically enhanced sound that influenced genres beyond jazz.[25] In contemporary classical music, composers have pushed the trumpet toward extended techniques, including microtonal explorations enabled by specialized instruments like quarter-tone trumpets. Luciano Berio's Sequenza X (1984) for solo trumpet and piano resonance demands multiphonics, flutter-tonguing, and subtle timbral shifts, challenging performers to exploit the instrument's acoustic nuances without electronic aids.[26] Similarly, works by composers such as Ibrahim Maalouf utilize quarter-tone valves to access Arabic maqam scales, bridging Western classical traditions with Middle Eastern modalities in pieces that require precise microtonal intonation.[27] Post-2010 innovations in manufacturing have introduced 3D-printed trumpet prototypes, allowing rapid customization of components like bells and leadpipes to optimize intonation and playability, as demonstrated in early models from Harrelson Trumpets that rival traditional brass in resonance. By 2025, 3D printing has enabled fully customizable trumpets, such as the Harrelson Bravura with printed stainless steel leadpipes, improving efficiency and reducing waste.[28] The trumpet's global reach has expanded through fusions with world music traditions, notably in Afrobeat, where Fela Kuti's horn sections—featuring prominent trumpet lines—drove the genre's propulsive rhythms and political commentary, influencing players like Muyiwa Kunnuji in ensembles such as Egypt 80.[29] In Klezmer, the trumpet adds buoyant, emotive brass colors to Eastern European Jewish melodies, as arranged in collections like 25 Klezmer Tunes for Trumpet, evoking dance-like freylekhs and doinas with agile ornamentation.[30] Amid these stylistic evolutions, 2020s manufacturing trends emphasize sustainability, with companies adopting sustainable materials and manufacturing processes to reduce environmental footprints while maintaining tonal integrity, reflecting broader industry shifts toward eco-friendly production.Design and Construction

Basic Components

The modern trumpet, particularly the standard B-flat model, consists of several core physical components that work together to produce sound through vibration and airflow. The mouthpiece is the initial point of contact for the player, featuring a rim that rests against the lips for comfort and stability, a cup where the lips vibrate to initiate the sound, and a backbore that tapers from the narrow throat to connect smoothly to the instrument's leadpipe.[31] The leadpipe, a curved tube extending from the mouthpiece receiver, directs the airflow into the main body and connects directly to the tuning slide, ensuring a consistent pathway for the air column.[32] The valve section forms the heart of the instrument's pitch-altering mechanism, typically comprising three piston valves housed in cylindrical casings. Each valve operates via a spring-loaded piston that, when depressed by finger buttons, redirects airflow through additional tubing loops to lower the pitch by semitones; the casings provide structural integrity, while the springs ensure quick return to the resting position.[32] Associated with the valves are the tuning slides: the first valve slide adjusts the pitch for the first valve alone, the third valve slide corrects intonation for lower notes involving the third valve, and the main tuning slide sets the overall pitch of the instrument.[32] The bell serves as the flared terminus of the trumpet, projecting the sound outward, while braces connect the bell to the valve section and other parts for rigidity and balance during play.[32] When uncoiled, the total tubing length of a B-flat trumpet measures approximately 1.48 meters, allowing for the fundamental pitch and harmonic series.[32] Assembly of these components begins with individual fabrication, followed by precise joining: craftsmen solder the bell, valve casings, leadpipe, and slides together to form a seamless structure, often using techniques like annealing to maintain shape integrity.[33] Final alignment involves meticulous adjustments to the valves and slides using tools like strobe checkers to ensure proper intonation across the range, with each instrument test-played before completion; materials such as brass are commonly selected for their acoustic properties and durability during this process.[33]Materials and Manufacturing

The primary material for most trumpets is yellow brass, an alloy composed of 70% copper and 30% zinc, which provides a bright, projecting tone suitable for orchestral and band settings.[34] Alternative materials include gold brass, with 85% copper and 15% zinc, for a warmer sound, or sterling silver for bells in custom models, offering a denser, more focused timbre.[34][35] Gold plating is sometimes applied to the interior of bells or leadpipes to enhance tonal warmth and corrosion resistance.[36] Trumpet manufacturing begins with forming the bell from sheet metal, typically through a process of cutting and welding flat brass sheets into a tapered cone, followed by spinning the cone over a rotating mandrel to achieve the precise flare and curvature.[37] Tubing for the leadpipe and valve loops is created by drawing annealed brass rods through progressively smaller dies to form seamless cylindrical sections, which are then bent to shape using hydraulic presses or mandrels.[38] For custom or high-end instruments, hand-hammering refines the bell's taper and thickness, allowing artisans to adjust the metal's grain structure for subtle tonal variations.[11] Modern production incorporates computer numerical control (CNC) machining, introduced widely since the 1980s, to mill valve casings and pistons with high precision, ensuring airtight seals and smooth action.[39] Valves are typically made from monel alloy for durability, with components brazed together and lapped for fit.[40] After assembly of these components into the full instrument, finishes are applied: clear lacquer for protection and a golden sheen, silver plating for brighter reflection, or raw unlacquered surfaces to promote natural patina and a more open tone.[41][36] Cost variations arise from material quality, craftsmanship, and features; student models, often machine-produced with basic yellow brass, start around $300 as of 2025, while professional trumpets with hand-hammered bells and premium alloys exceed $4,000.[42]Acoustics and Physics

The trumpet produces sound through a reedless mechanism where the player's lips vibrate against the mouthpiece, acting as a valve that modulates airflow into the instrument's air column. This lip vibration, driven by the player's embouchure tension and breath pressure, generates periodic pressure pulses that excite standing waves within the bore, with a pressure antinode at the mouthpiece (effectively a closed end) and a node at the bell (open end).[43][44] The resulting resonances form a harmonic series dominated by overtones, as the weak fundamental (pedal note) is often inaudible or simulated by higher partials in ratios approximating 2:3:4:5..., enabling the instrument's characteristic brassy timbre.[43][44] The trumpet's primarily cylindrical bore contributes to its brighter, more projecting tone by producing a spectrum rich in odd harmonics, while a more conical bore—as found in related instruments like the cornet—yields a mellower sound with a fuller harmonic series closer to even multiples. The bell's exponential flare plays a crucial role in sound projection by gradually matching the acoustic impedance between the air column and the external environment, efficiently radiating higher harmonics and enhancing directivity without abrupt reflections that could dampen output.[43][44][45] Valves alter the effective length of the air column to access the chromatic scale: the second valve extends the length by approximately 5.9% to lower pitch by one semitone, the first valve by about 12.2% for a whole tone, and the third by roughly 18.9% for three semitones. Combinations like the first and third valves together extend the length by approximately 31.1%, but these fixed ratios do not perfectly align with the logarithmic pitch intervals required for equal temperament.[45][43] Intonation challenges arise because the trumpet's natural harmonic series deviates from the equal-tempered scale; for instance, the seventh harmonic falls between A and B♭ (about 31 cents flat relative to tempered B♭ in a C major context), and the eleventh is similarly mistuned, requiring players to adjust lip tension or use compensatory slides to approximate tempered intervals.[44][46][43]Types and Variants

Valved Trumpets

The valved trumpet, the predominant form in contemporary music, employs valves to enable chromatic playing across a wide range. The B-flat (B♭) trumpet serves as the standard instrument, pitched such that it sounds a major second lower than the written notation, allowing performers to read music transposed upward by that interval for ease of fingering in the instrument's natural harmonic series.[47] This design aligns with the international concert pitch standard of A=440 Hz, ensuring consistent tuning in ensembles.[48] The B♭ trumpet's versatility makes it essential for genres ranging from orchestral works to jazz and popular music, with its range typically spanning from E below middle C to high C above the staff when sounding.[49] Other common valved trumpets include the C trumpet, which sounds as written and is preferred in orchestral settings for its brighter tone and simpler transposition in certain repertoire; the D trumpet, used for fanfares and some Baroque works; and the E♭ trumpet, favored for its projection in solo and British brass band contexts. These variants share similar construction to the B♭ model but are pitched higher, with the C trumpet sounding a major second above the B♭, the D a major third, and the E♭ a perfect fourth.[50][51] Valved trumpets primarily utilize either piston or rotary valves to lengthen the tubing and lower the pitch. Piston valves, named after their inventor François Périnet, move vertically for a quick, direct action that facilitates rapid note changes and precise articulation, particularly suited to American and French styles.[52] In contrast, rotary valves rotate on an axis to redirect airflow, offering smoother slides between notes and a more legato response, which is favored in German and Austrian traditions for its blended tone in orchestral settings.[53] The French system typically employs piston valves for brighter projection, while the German system uses rotary valves for a darker, more centered sound, influencing repertoire choices in professional ensembles.[54] Both types generally feature three valves, with the first, second, and third lowering the pitch by two, one, and three semitones respectively, though modern instruments may include a fourth valve for extended low range.[55] Piccolo trumpets represent a high-pitched variant of the valved design, scaled down to produce brighter, more piercing tones an octave above the standard B♭ model. Commonly built in E♭, D, or C, these instruments facilitate performance of Baroque repertoire originally composed for high clarino trumpets, such as works by Bach and Handel, by matching the required transposition and tessitura without excessive strain.[56] The D piccolo, for instance, allows direct reading of D-major parts common in the period, while the C version aids in G-major transpositions, enhancing intonation and fingerings for modern performers.[57] Their compact size—often with a bell diameter under 100 mm—demands refined embouchure control but delivers exceptional clarity in solo and ensemble contexts.[58] Bass trumpets extend the valved family into lower registers, pitched in B♭ or C to sound an octave below the standard trumpet, providing a robust, tenor-like voice. These instruments gained prominence through Richard Wagner's orchestration in his Ring cycle operas, where the bass trumpet in B♭ underscores dramatic scenes with its powerful, grounded timbre akin to a piston-valved trombone.[59] The C bass trumpet offers similar utility but transposes differently for specific scores, maintaining the valved mechanism for chromatic agility in Wagnerian and later Romantic works by composers like Stravinsky.[60] With bores around 13-15 mm and upright bells for projection, bass trumpets blend seamlessly in large ensembles while requiring adjusted breath support for their extended tubing length.[49]Natural and Baroque Trumpets

The natural trumpet is a valveless brass instrument that produces notes exclusively from the harmonic series, resulting in a fully diatonic scale limited to the natural overtones of its fundamental pitch.[61] Constructed from a long, mostly cylindrical tube folded into a compact shape and ending in a flared bell, it typically measures about 8 feet in uncoiled length for the common C model, with the fundamental pitch at C3 (approximately 130 Hz).[62] To adapt to different keys, players insert removable crooks—additional sections of tubing inserted near the mouthpiece—that lengthen the instrument and lower the pitch, such as extending a D trumpet (fundamental D3) to C with an added crook.[61] This design, prevalent from the Renaissance through the Baroque era, relies on the player's lip vibration to select partials from the 8th to 20th harmonics for the brilliant "clarino" register or lower partials for fanfare-like "principale" tones.[63] Baroque trumpets evolved from the natural form with modifications to achieve limited chromaticism, primarily through slide mechanisms or rudimentary keys, though these often compromised the instrument's pure timbre and intonation.[63] The slide trumpet, or tromba da tirarsi, featured a movable leadpipe section allowing brief extensions for accidentals, as notated in works by J.S. Bach such as Cantata BWV 67, but it proved unreliable for rapid passages due to mechanical awkwardness.[63] Some late Baroque models incorporated finger-operated keys or small holes to facilitate out-of-tune harmonics, yet these innovations remained marginal, preserving the instrument's diatonic essence for use in period ensembles performing music by composers like Handel and Purcell.[63] In authentic performance practice, these trumpets demand precise embouchure control to navigate the harmonic series, with the lowest playable note being the pedal C (fundamental) without aids like vent holes, which were not part of original designs and could alter acoustics unfavorably.[63] Modern replicas of natural and Baroque trumpets, crafted by specialized makers, enable contemporary musicians to recreate historical sounds in period-instrument ensembles.[64] Firms like Ewald Meinl produce hand-hammered instruments based on 17th-century originals, such as those by Wolf Magnus Ehe I, featuring interchangeable tuning slides in keys like C, D♭, and C♭, along with optional transposing holes for intonation in the clarino register.[65] These replicas, often in silver-plated brass with Baroque-style decorations, prioritize historical accuracy while accommodating modern pitch standards (A=440 Hz), supporting performances of early music without valves.[65] The three-hole system pioneered by Meinl in the 1970s, for instance, allows subtle adjustments but can be removed for purist natural play.[64]Specialized and Modern Variants

The flugelhorn serves as a mellow relative to the standard trumpet, featuring a predominantly conical bore that produces a warmer, darker tone compared to the trumpet's brighter, cylindrical sound. This design, which includes a wider bell and deeper conical tubing, makes it particularly suited for lyrical passages in jazz and brass band ensembles.[66][1] The cornet, another close variant, shares the trumpet's valved mechanism but employs a more conical bore and compact, coiled tubing for easier handling in marching and brass bands. Its mellower timbre and smaller size facilitated widespread adoption in 19th-century military bands, where it excelled in melodic and solo roles.[67][68] Pocket trumpets represent a modern compact variant, with tubing wound into a smaller coil—often around 36 cm in length—while retaining a standard-sized bell to preserve projection and tone for travel or portability. These instruments maintain the full B♭ pitch range of conventional trumpets, allowing performers to practice or perform in confined spaces without significant loss in playability.[69][70] Silent practice models, developed prominently since the early 2000s, incorporate resistance systems to simulate the airflow and backpressure of a traditional trumpet while minimizing audible output. Yamaha's SILENT Brass system, for instance, uses a pickup mute paired with a personal studio unit employing brass resonance modeling to replicate tonal nuances through headphones, enabling quiet practice without altering embouchure habits.[71][72] Electric trumpets integrate piezoelectric pickups, such as those mounted near the bell or mouthpiece, to capture vibrations for electronic amplification and effects processing. These modifications allow integration with guitar amplifiers or digital setups, expanding applications in contemporary music genres like fusion and electronic improvisation.[73] Hybrid designs like the superbone combine trumpet-like valve mechanisms with trombone slide functionality in a single B♭ instrument, offering versatility for jazz performers who alternate between valved precision and slide glissandi. This duplex construction, pioneered in the mid-20th century, bridges the tonal worlds of trumpet and trombone for seamless doubling.[74] Ethnic variants include the Indian ransingha, a curved natural trumpet crafted from copper or brass alloys, used in ceremonial processions to announce royalty or mark festivals with its resonant, piercing calls. In African traditions, the Hausa kakaki—a long, straight metal trumpet extending up to four meters—serves similar royal and communal roles, its powerful blasts signaling authority during ceremonies in West African societies.[75][76][77][78]Playing Fundamentals

Embouchure and Breath Control

The embouchure on the trumpet refers to the precise formation and coordination of the lips, facial muscles, and oral cavity to produce a controlled vibration, or buzz, against the mouthpiece rim. This vibration initiates sound production, with the lips forming a small, adjustable aperture—typically 1-2 mm wide for fundamental pitches—that allows air to pass through while maintaining sufficient tension for oscillation at the desired frequency. Optimal lip tension is moderate, engaging the orbicularis oris and buccinator muscles to create a firm yet flexible seal, enabling the lips to vibrate freely without excessive rigidity.[79][80] Common errors in embouchure formation include over-biting, where excessive jaw or mouthpiece pressure pinches the lips, leading to restricted vibration, fatigue, and a thin tone quality. Another frequent issue is uneven lip alignment, such as rolling the lower lip too far over the teeth, which can cause air leakage and inconsistent buzzing; instead, the lips should meet naturally with the mouthpiece centered at about two-thirds on the upper lip. Puckering or smiling excessively also disrupts the aperture, reducing endurance by introducing unnecessary tension in the zygomaticus muscles.[81][82] Breath control is integral to sustaining the embouchure, relying on diaphragmatic breathing to draw air deeply into the lower lungs, expanding the abdomen and lower rib cage for a reservoir of 3-4 liters of air in trained players. This technique supports steady airflow, where air speed—generated by controlled abdominal contraction—determines the attack and clarity of notes, while volume modulates sustain and overall projection. For dynamics, players adjust the balance between air speed (faster for brighter, louder tones) and volume (slower for softer passages), avoiding shallow chest breathing that limits endurance and causes rapid fatigue. The mouthpiece's cup depth and rim contour can influence this balance by affecting how the embouchure interacts with incoming air.[83][84] Warm-up routines emphasize embouchure and breath integration to build control and prevent injury. Long tones, played on a single pitch with gradual crescendo and diminuendo over 8-16 seconds, develop sustained airflow and even vibration, starting from low registers to foster relaxation. Lip buzzes, performed without or with the mouthpiece alone, isolate the embouchure by producing free vibrations across a limited range, enhancing muscle coordination and reducing mouthpiece dependency for endurance. These exercises, typically 10-15 minutes daily, progressively increase duration to condition the lips for extended sessions.[85][82] Physiologically, regular trumpet playing strengthens the facial musculature, particularly the orbicularis oris and buccinator, leading to greater cheek strength and lip endurance compared to non-players; lip strength shows no significant difference. Over time, this adaptation enhances muscle fiber recruitment and reduces fatigue during prolonged vibrations, though overuse can strain tissues if not balanced with rest. Studies confirm that these changes support finer control of aperture and tension, contributing to improved tone stability.[86][87]Fingering and Valve Techniques

The modern trumpet typically features three piston valves operated by the fingers of the right hand, which lengthen the instrument's tubing to lower the pitch: the first valve by a whole step, the second by a half step, and the third by one and a half steps.[88] By combining these valves (e.g., 1 and 2 for a minor third, 1 and 3 for a tritone, or all three for a major sixth), players achieve a full chromatic scale across the instrument's range.[88] These dependent valve systems, where the third valve's slide can be extended via a trigger for intonation adjustment, require coordinated finger placement: the index finger on the first valve, middle on the second, and ring on the third, with the pinky supporting the valve casing.[89] For the standard B♭ trumpet, common valve fingerings follow a repeating pattern based on the harmonic series, with open valves producing the pedal tones and partial combinations filling the gaps. Below is a representative fingering chart for the primary playing range (low C to high C, written pitch for B♭ trumpet; sounds a major second lower in concert pitch):| Note (Written Pitch) | Valve 1 | Valve 2 | Valve 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low C (Pedal C) | Open | Open | Open |

| D | ● | Open | Open |

| E♭ | Open | ● | ● |

| E | Open | ● | Open |

| F | ● | ● | Open |

| F♯ | ● | Open | ● |

| G | Open | Open | Open |

| A♭ | ● | ● | ● |

| A | Open | ● | Open |

| B♭ | ● | ● | Open |

| B | ● | Open | ● |

| Middle C | Open | Open | Open |

| D | ● | Open | Open |

| E♭ | Open | ● | ● |

| E | Open | ● | Open |

| F | ● | ● | Open |

| F♯ | ● | Open | ● |

| G | Open | Open | Open |

| A♭ | ● | ● | ● |

| A | Open | ● | Open |

| B♭ | ● | ● | Open |

| B | ● | Open | ● |

| High C | Open | Open | Open |