Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Buffer solution

View on WikipediaA buffer solution is a solution where the pH does not change significantly on dilution or if an acid or base is added at constant temperature.[1] Its pH changes very little when a small amount of strong acid or base is added to it. Buffer solutions are used as a means of keeping pH at a nearly constant value in a wide variety of chemical applications. In nature, there are many living systems that use buffering for pH regulation. For example, the bicarbonate buffering system is used to regulate the pH of blood, and bicarbonate also acts as a buffer in the ocean.

Principles of buffering

[edit]

Buffer solutions resist pH change because of a chemical equilibrium between the weak acid HA and its conjugate base A−:

When some strong acid is added to an equilibrium mixture of the weak acid and its conjugate base, hydrogen ions (H+) are added, and the equilibrium is shifted to the left, in accordance with Le Chatelier's principle. Because of this, the hydrogen ion concentration increases by less than the amount expected for the quantity of strong acid added. Similarly, if strong alkali is added to the mixture, the hydrogen ion concentration decreases by less than the amount expected for the quantity of alkali added. In Figure 1, the effect is illustrated by the simulated titration of a weak acid with pKa = 4.7. The relative concentration of undissociated acid is shown in blue, and of its conjugate base in red. The pH changes relatively slowly in the buffer region, pH = pKa ± 1, centered at pH = 4.7, where [HA] = [A−]. The hydrogen ion concentration decreases by less than the amount expected because most of the added hydroxide ion is consumed in the reaction

and only a little is consumed in the neutralization reaction (which is the reaction that results in an increase in pH)

Once the acid is more than 95% deprotonated, the pH rises rapidly because most of the added alkali is consumed in the neutralization reaction.

Buffer capacity

[edit]Buffer capacity is a quantitative measure of the resistance to change of pH of a solution containing a buffering agent with respect to a change of acid or alkali concentration. It can be defined as follows:[2][3] where is an infinitesimal amount of added base, or where is an infinitesimal amount of added acid. pH is defined as −log10[H+], and d(pH) is an infinitesimal change in pH.

With either definition the buffer capacity for a weak acid HA with dissociation constant Ka can be expressed as[4][5][3] where [H+] is the concentration of hydrogen ions, and is the total concentration of added acid. Kw is the equilibrium constant for self-ionization of water, equal to 1.0×10−14. Note that in solution H+ exists as the hydronium ion H3O+, and further aquation of the hydronium ion has negligible effect on the dissociation equilibrium, except at very high acid concentration.

This equation shows that there are three regions of raised buffer capacity (see figure 2).

- In the central region of the curve (colored green on the plot), the second term is dominant, and Buffer capacity rises to a local maximum at pH = pKa. The height of this peak depends on the value of pKa. Buffer capacity is negligible when the concentration [HA] of buffering agent is very small and increases with increasing concentration of the buffering agent.[3] Some authors show only this region in graphs of buffer capacity.[2] Buffer capacity falls to 33% of the maximum value at pH = pKa ± 1, to 10% at pH = pKa ± 1.5 and to 1% at pH = pKa ± 2. For this reason the most useful range is approximately pKa ± 1. When choosing a buffer for use at a specific pH, it should have a pKa value as close as possible to that pH.[2]

- With strongly acidic solutions, pH less than about 2 (coloured red on the plot), the first term in the equation dominates, and buffer capacity rises exponentially with decreasing pH: This results from the fact that the second and third terms become negligible at very low pH. This term is independent of the presence or absence of a buffering agent.

- With strongly alkaline solutions, pH more than about 12 (coloured blue on the plot), the third term in the equation dominates, and buffer capacity rises exponentially with increasing pH: This results from the fact that the first and second terms become negligible at very high pH. This term is also independent of the presence or absence of a buffering agent.

Applications of buffers

[edit]The pH of a solution containing a buffering agent can only vary within a narrow range, regardless of what else may be present in the solution. In biological systems this is an essential condition for enzymes to function correctly. For example, in human blood a mixture of carbonic acid (H

2CO

3) and bicarbonate (HCO−

3) is present in the plasma fraction; this constitutes the major mechanism for maintaining the pH of blood between 7.35 and 7.45. Outside this narrow range (7.40 ± 0.05 pH unit), acidosis and alkalosis metabolic conditions rapidly develop, ultimately leading to death if the correct buffering capacity is not rapidly restored.

If the pH value of a solution rises or falls too much, the effectiveness of an enzyme decreases in a process, known as denaturation, which is usually irreversible.[6] The majority of biological samples that are used in research are kept in a buffer solution, often phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4.

In industry, buffering agents are used in fermentation processes and in setting the correct conditions for dyes used in colouring fabrics. They are also used in chemical analysis[5] and calibration of pH meters.

Simple buffering agents

[edit]Buffering agent pKa Useful pH range Citric acid 3.13, 4.76, 6.40 2.1–7.4 Acetic acid 4.7 3.8–5.8 KH2PO4 7.2 6.2–8.2 CHES 9.3 8.3–10.3 Borate 9.24 8.25–10.25

For buffers in acid regions, the pH may be adjusted to a desired value by adding a strong acid such as hydrochloric acid to the particular buffering agent. For alkaline buffers, a strong base such as sodium hydroxide may be added. Alternatively, a buffer mixture can be made from a mixture of an acid and its conjugate base. For example, an acetate buffer can be made from a mixture of acetic acid and sodium acetate. Similarly, an alkaline buffer can be made from a mixture of the base and its conjugate acid.

"Universal" buffer mixtures

[edit]By combining substances with pKa values differing by only two or less and adjusting the pH, a wide range of buffers can be obtained. Citric acid is a useful component of a buffer mixture because it has three pKa values, separated by less than two. The buffer range can be extended by adding other buffering agents. The following mixtures (McIlvaine's buffer solutions) have a buffer range of pH 3 to 8.[7]

0.2 M Na2HPO4 (mL) 0.1 M citric acid (mL) pH 20.55 79.45 3.0 38.55 61.45 4.0 51.50 48.50 5.0 63.15 36.85 6.0 82.35 17.65 7.0 97.25 2.75 8.0

A mixture containing citric acid, monopotassium phosphate, boric acid, and diethyl barbituric acid can be made to cover the pH range 2.6 to 12.[8]

Other universal buffers are the Carmody buffer[9] and the Britton–Robinson buffer, developed in 1931.

Common buffer compounds used in biology

[edit]For effective range see Buffer capacity, above. Also see Good's buffers for the historic design principles and favourable properties of these buffer substances in biochemical applications.

| Common name (chemical name) | Structure | pKa, 25 °C |

Temp. effect, dpH/dT (K−1)[10] |

Mol. weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAPS, ([tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propanesulfonic acid) |

|

8.43 | −0.018 | 243.3 |

| Bicine, (2-(bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino)acetic acid) |

|

8.35 | −0.018 | 163.2 |

| Tris, (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, or 2-amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol) |

|

8.07[a] | −0.028 | 121.14 |

| Tricine, (N-[tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]glycine) |

|

8.05 | −0.021 | 179.2 |

| TAPSO, (3-[N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]-2-hydroxypropanesulfonic acid) |

|

7.635 | 259.3 | |

| HEPES, (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) |

|

7.48 | −0.014 | 238.3 |

| TES, (2-[[1,3-dihydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)propan-2-yl]amino]ethanesulfonic acid) |

|

7.40 | −0.020 | 229.20 |

| MOPS, (3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid) |

|

7.20 | −0.015 | 209.3 |

| PIPES, (piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)) |

|

6.76 | −0.008 | 302.4 |

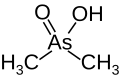

| Cacodylate, (dimethylarsenic acid) |

|

6.27 | 138.0 | |

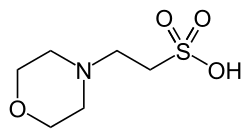

| MES, (2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid) |

|

6.15 | −0.011 | 195.2 |

- ^ Tris is a base, the pKa = 8.07 refers to its conjugate acid.

Calculating buffer pH

[edit]Monoprotic acids

[edit]First write down the equilibrium expression

This shows that when the acid dissociates, equal amounts of hydrogen ion and anion are produced. The equilibrium concentrations of these three components can be calculated in an ICE table (ICE standing for "initial, change, equilibrium").

ICE table for a monoprotic acid [HA] [A−] [H+] I C0 0 y C −x x x E C0 − x x x + y

The first row, labelled I, lists the initial conditions: the concentration of acid is C0, initially undissociated, so the concentrations of A− and H+ would be zero; y is the initial concentration of added strong acid, such as hydrochloric acid. If strong alkali, such as sodium hydroxide, is added, then y will have a negative sign because alkali removes hydrogen ions from the solution. The second row, labelled C for "change", specifies the changes that occur when the acid dissociates. The acid concentration decreases by an amount −x, and the concentrations of A− and H+ both increase by an amount +x. This follows from the equilibrium expression. The third row, labelled E for "equilibrium", adds together the first two rows and shows the concentrations at equilibrium.

To find x, use the formula for the equilibrium constant in terms of concentrations:

Substitute the concentrations with the values found in the last row of the ICE table:

Simplify to

With specific values for C0, Ka and y, this equation can be solved for x. Assuming that pH = −log10[H+], the pH can be calculated as pH = −log10(x + y).

Polyprotic acids

[edit]

Polyprotic acids are acids that can lose more than one proton. The constant for dissociation of the first proton may be denoted as Ka1, and the constants for dissociation of successive protons as Ka2, etc. Citric acid is an example of a polyprotic acid H3A, as it can lose three protons.

Stepwise dissociation constants Equilibrium Citric acid H3A ⇌ H2A− + H+ pKa1 = 3.13 H2A− ⇌ HA2− + H+ pKa2 = 4.76 HA2− ⇌ A3− + H+ pKa3 = 6.40

When the difference between successive pKa values is less than about 3, there is overlap between the pH range of existence of the species in equilibrium. The smaller the difference, the more the overlap. In the case of citric acid, the overlap is extensive and solutions of citric acid are buffered over the whole range of pH 2.5 to 7.5.

Calculation of the pH with a polyprotic acid requires a speciation calculation to be performed. In the case of citric acid, this entails the solution of the two equations of mass balance:

CA is the analytical concentration of the acid, CH is the analytical concentration of added hydrogen ions, βq are the cumulative association constants. Kw is the constant for self-ionization of water. There are two non-linear simultaneous equations in two unknown quantities [A3−] and [H+]. Many computer programs are available to do this calculation. The speciation diagram for citric acid was produced with the program HySS.[11]

N.B. The numbering of cumulative, overall constants is the reverse of the numbering of the stepwise, dissociation constants.

Relationship between cumulative association constant (β) values and stepwise dissociation constant (K) values for a tribasic acid. Equilibrium Relationship A3− + H+ ⇌ AH2+ Log β1= pka3 A3− + 2H+ ⇌ AH2+ Log β2 =pka2 + pka3 A3− + 3H+⇌ AH3 Log β3 = pka1 + pka2 + pka3

Cumulative association constants are used in general-purpose computer programs such as the one used to obtain the speciation diagram above.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ J. Gordon Betts (25 April 2013). "Inorganic compounds essential to human functioning". Anatomy and Physiology. OpenStax. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Skoog, Douglas A.; West, Donald M.; Holler, F. James; Crouch, Stanley R. (2014). Fundamentals of Analytical Chemistry (9th ed.). Brooks/Cole. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-495-55828-6.

- ^ a b c Urbansky, Edward T.; Schock, Michael R. (2000). "Understanding, Deriving and Computing Buffer Capacity". Journal of Chemical Education. 77 (12): 1640–1644. Bibcode:2000JChEd..77.1640U. doi:10.1021/ed077p1640.

- ^ Butler, J. N. (1998). Ionic Equilibrium: Solubility and pH calculations. Wiley. pp. 133–136. ISBN 978-0-471-58526-8.

- ^ a b Hulanicki, A. (1987). Reactions of acids and bases in analytical chemistry. Translated by Masson, Mary R. Horwood. ISBN 978-0-85312-330-9.

- ^ Scorpio, R. (2000). Fundamentals of Acids, Bases, Buffers & Their Application to Biochemical Systems. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7872-7374-3.

- ^ McIlvaine, T. C. (1921). "A buffer solution for colorimetric comparaison" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 49 (1): 183–186. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)86000-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-02-26.

- ^ Mendham, J.; Denny, R. C.; Barnes, J. D.; Thomas, M. (2000). "Appendix 5". Vogel's textbook of quantitative chemical analysis (5th ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-582-22628-9.

- ^ Carmody, Walter R. (1961). "Easily prepared wide range buffer series". J. Chem. Educ. 38 (11): 559–560. Bibcode:1961JChEd..38..559C. doi:10.1021/ed038p559.

- ^ "Buffer Reference Center". Sigma-Aldrich. Archived from the original on 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ^ Alderighi, L.; Gans, P.; Ienco, A.; Peters, D.; Sabatini, A.; Vacca, A. (1999). "Hyperquad simulation and speciation (HySS): a utility program for the investigation of equilibria involving soluble and partially soluble species". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 184 (1): 311–318. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(98)00260-4. Archived from the original on 2007-07-04.

External links

[edit]"Biological buffers". REACH Devices.

Buffer solution

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Buffer Solutions

Definition and Composition

A buffer solution is an aqueous mixture containing a weak acid and its conjugate base, or a weak base and its conjugate acid, designed to resist substantial changes in pH upon the addition of small quantities of a strong acid or strong base.[1][2] This resistance arises from the equilibrium between the acid-base pair, which allows the solution to absorb added protons or hydroxide ions without drastic pH shifts.[10] The typical composition of a buffer solution includes the weak acid or base as the primary buffering agent and a salt that supplies the corresponding conjugate species to establish the necessary equilibrium. For instance, an acetate buffer comprises acetic acid (CH₃COOH) and sodium acetate (CH₃COONa), where the salt dissociates to provide acetate ions (CH₃COO⁻). The relative concentrations of the acid and conjugate base play a key role in setting the buffer's pH, with balanced ratios promoting optimal performance around the pKa value.[11] Effective buffering requires the pKa of the weak acid (or pKb of the weak base) to be near the target pH, generally within one pH unit, to ensure sufficient concentrations of both species. Qualitative influences such as the solution's ionic strength, which can alter ion activities, and temperature, which affects dissociation equilibria, must also be considered for reliable performance.[12][13] The term "buffer" originated in 1914, coined by G. S. Walpole to describe stabilizing mixtures in biological and chemical contexts.[14]Mechanism of pH Resistance

Buffer solutions resist changes in pH through dynamic chemical equilibria involving weak acids and their conjugate bases, or weak bases and their conjugate acids. In a weak acid buffer, such as acetic acid (HA) and acetate ion (A⁻), the equilibrium is established as . When a strong base, like hydroxide ions (OH⁻), is added, the OH⁻ reacts with free H⁺ to form water, reducing the H⁺ concentration and disturbing the equilibrium. According to Le Châtelier's principle, the system responds by shifting the equilibrium to the right, dissociating more HA to replenish H⁺ and thus minimizing the pH increase. Conversely, addition of a strong acid introduces excess H⁺, which combines with A⁻ to form undissociated HA, shifting the equilibrium to the left and consuming the added H⁺ to limit the pH decrease.[15] For weak base buffers, exemplified by ammonia (B) and ammonium ion (BH⁺), the relevant equilibrium is . Addition of a strong acid provides H⁺ that reacts with OH⁻ to form water, decreasing OH⁻ and prompting the equilibrium to shift right, producing more OH⁻ from B to counteract the pH drop. If a strong base is added, excess OH⁻ reacts with BH⁺ to form B and water, shifting the equilibrium left to regenerate BH⁺ and reduce the pH rise. This application of Le Châtelier's principle ensures that the added ions are effectively neutralized by the buffer components without significantly altering the H⁺ or OH⁻ concentrations.[16] Buffers have inherent limitations in their pH resistance. They fail when large quantities of acid or base are added, exceeding the available concentrations of the buffering species and depleting one component, after which the solution behaves like a non-buffered one with drastic pH changes. Effectiveness is also reduced if the solution's pH deviates significantly from the pKa of the weak acid or base, as the equilibrium favors one form over the other, limiting the buffer's ability to absorb perturbations. Dilution with water causes only minor pH shifts due to slight changes in ionic equilibria, but extreme dilution can diminish buffering capacity by reducing component concentrations.[17][18]Buffer Capacity and Effectiveness

Quantitative Definition

Buffer capacity, denoted as β, quantifies the resistance of a buffer solution to pH changes upon addition of acid or base. It is defined as the number of moles of strong acid or strong base required to alter the pH of one liter of the buffer solution by one unit.[19] This measure arises from the buffer's ability to absorb added H⁺ or OH⁻ through equilibrium shifts, with higher values indicating stronger buffering action.[20] For a monoprotic buffer consisting of a weak acid HA and its conjugate base A⁻, the buffer capacity can be approximated using the Van Slyke equation derived from the Henderson-Hasselbalch relation. The Henderson-Hasselbalch equation is pH = pK_a + \log_{10} \left( \frac{[A^-]}{[HA]} \right). Differentiating with respect to added base B (where d[A^-] = -d[HA] = dB for small additions, neglecting [H⁺] and [OH⁻] contributions), yields β = \frac{dB}{dpH} \approx 2.303 \frac{[HA][A^-]}{[HA] + [A^-]}, where 2.303 is \ln(10).[20] This approximation holds when the buffer concentration is sufficiently high relative to [H⁺] and [OH⁻]. The capacity reaches its maximum when pH = pK_a, corresponding to [HA] = [A^-] = \frac{C}{2}, where C is the total buffer concentration ([HA] + [A^-]), giving β_{max} \approx 0.576 C.[20] Buffer capacity is typically expressed in units of moles per liter per pH unit (mol L⁻¹ pH⁻¹). Experimentally, it is determined through titration: a known volume of buffer is titrated with standardized strong acid or base while monitoring pH, and β is calculated as the moles of titrant added per liter divided by the observed pH change (often averaged over a ±0.5 pH range around the buffer pH for accuracy).[21] A higher β signifies better pH stability, with the 1:1 [HA]:[A⁻] ratio providing optimal resistance for a given concentration, though actual capacity also depends on the total buffer amount present.[20]Factors Affecting Capacity

The buffer capacity of a solution increases with the total concentration of the buffering components, as higher concentrations provide more weak acid and conjugate base molecules available to neutralize added acid or base, up to the limits imposed by solubility and stability of the buffer species.[22] For a fixed amount of buffer solute, diluting the solution by increasing its volume reduces the concentration and thereby decreases the buffer capacity per unit volume, though the total capacity across the entire volume remains constant.[22] Buffer capacity exhibits a strong dependence on the deviation between the solution's pH and the buffer's pKa value, reaching a maximum at pH = pKa and declining rapidly outside the range of pH = pKa ± 1 unit. This relationship arises because the capacity is proportional to the product of the concentrations of the acid and conjugate base forms, which is optimized when their ratio is 1:1. Beyond this range, the buffer becomes less effective, with capacity dropping to about half its maximum at pH = pKa ± 1 and approaching zero farther away, as illustrated by the bell-shaped curve of buffer capacity versus pH, centered at the pKa.[22] The ratio of conjugate base to acid in the buffer mixture also influences capacity, with the optimal performance occurring at a 1:1 ratio (pH = pKa), but buffers remain functional at extreme ratios such as 10:1 or 1:10, corresponding to pH = pKa ± 1, where capacity is reduced but still significant within the effective pH range.[22] Temperature affects buffer capacity indirectly through shifts in the pKa value, which depend on the enthalpy of the dissociation reaction: endothermic dissociations increase pKa with rising temperature, while exothermic ones decrease it. These shifts alter the pH-pKa alignment and thus the effective capacity at a given temperature. Representative temperature coefficients (ΔpKa/ΔT) for common buffers are provided below; negative values indicate a decrease in pKa with increasing temperature, which is typical for many biological buffers.| Buffer System | pKa (25°C) | ΔpKa/ΔT (°C⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|

| Acetate (acetic acid) | 4.76 | -0.0002 |

| Phosphate (pK₂) | 7.20 | -0.0028 |

| Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane) | 8.06 | -0.031 |

| Carbonate (pK₂) | 10.33 | -0.0096 |

Types of Buffer Solutions

Simple Buffering Agents

Simple buffering agents are solutions composed of a single weak acid and its conjugate base, or a weak base and its conjugate acid, which together resist pH changes upon addition of small amounts of acid or base.[26] These systems rely on the equilibrium between the acid and its salt to maintain stability, typically effective within approximately 1 pH unit of the acid's pKa value. Preparation of simple buffers commonly involves dissolving equimolar amounts of the weak acid and its conjugate base salt in water to achieve a pH near the pKa.[27] Alternatively, partial neutralization of the weak acid with a strong base (or vice versa) can produce the desired ratio of acid to conjugate, or existing solutions can be adjusted by adding small volumes of strong acid or base to fine-tune the pH.[27] Stock solutions of these components are often prepared separately and mixed to create working buffers, ensuring consistency and ease of use in laboratory settings.[28] Common examples include the acetate buffer, formed from acetic acid (pKa 4.76 at 25°C) and sodium acetate, which operates effectively in the pH range of 3.6 to 5.6.[29][30] Citrate buffers, using citric acid (pKa values 3.13, 4.76, and 6.40 at 25°C) in a simple pair such as the first dissociation with its monosodium salt, provide buffering around pH 3 to 5 or 4 to 6 depending on the selected pair.[29] Borate buffers, derived from boric acid (pKa 9.24 at 25°C) and sodium borate, are suitable for alkaline conditions in the pH range of 8 to 10.[31] These agents offer advantages such as straightforward preparation and low cost, making them accessible for routine applications.[30] However, their buffering range is inherently narrow, limited to about ±1 pH unit from the pKa, and certain options like borate buffers carry potential toxicity risks, including reproductive harm from boron exposure.[32]Universal Buffer Mixtures

Universal buffer mixtures are formulations combining multiple buffering agents to provide effective pH control across a broad range, typically from pH 2 to 12, allowing researchers to maintain consistent ionic environments without preparing entirely new solutions for different pH values.[33] These systems rely on the overlapping pKa values of the constituent weak acids and their conjugates, enabling sequential dominance of buffering action as pH changes.[34] Prominent examples include the Britton-Robinson buffer, developed in 1931, which consists of 0.04 M each of acetic acid, orthophosphoric acid, and boric acid, with the pH adjusted using 0.2 M sodium hydroxide to cover the range from pH 2 to 12.[33] Another widely used formulation is the McIlvaine buffer, introduced in 1921, comprising 0.1 M citric acid and 0.2 M disodium hydrogen phosphate mixed in varying proportions to achieve pH values from 2.2 to 8.0. Phosphate-based variants attributed to Sørensen, such as the standard 0.067 M sodium phosphate buffer (combining Na₂HPO₄ and KH₂PO₄), provide coverage in the narrower range of pH 5.8 to 8.0 but can be modified with additional components for extended utility in universal applications.[35] Preparation of these mixtures typically involves dissolving the acid components in deionized water to form a stock solution, followed by stepwise addition of a strong base like NaOH while monitoring pH with a calibrated electrode, ensuring gradual titration to avoid overshooting.[36] For instance, in the Britton-Robinson system, the acids are combined first, then NaOH is added incrementally until the target pH is reached, with final volume adjustment using water.[37] Stability concerns arise during this process, including potential precipitation of borates or phosphates at extreme pH values, which can occur if ionic strength is not controlled or if incompatible ions are present, necessitating careful storage at 4°C and use within weeks to minimize degradation.[38] The primary advantage of universal buffer mixtures is their versatility, enabling experiments across wide pH ranges with a single base formulation, which simplifies workflows in electrochemical, spectroscopic, and solubility studies.[39] However, this comes at the cost of increased complexity in preparation compared to single-component buffers, potential chemical interactions between agents that may alter ionic strength or introduce artifacts, and reduced buffering capacity per pH unit due to the distributed concentrations of individual components.[34]Biological Buffer Systems

Biological buffer systems encompass a range of buffering agents specifically developed or selected for compatibility with living organisms and biochemical processes, ensuring minimal interference with cellular functions while maintaining stable pH in physiological ranges. These buffers are essential in research involving enzymes, proteins, and cell cultures, where pH fluctuations can denature biomolecules or disrupt metabolic pathways. Unlike general-purpose buffers, biological ones prioritize properties that support biocompatibility, such as solubility in aqueous media and low toxicity to cells.[40][41] The development of modern biological buffers traces back to the 1960s, when biochemist Norman Good and colleagues introduced a series of zwitterionic compounds known as Good's buffers to address limitations of traditional agents like phosphate or acetate in biochemical experiments. These buffers were engineered for use in studies of proteins and cellular organelles, offering enhanced stability and reduced interaction with biological components compared to earlier options. Their zwitterionic structure—featuring both positive and negative charges—contributes to high solubility and ionic strength mimicry of physiological conditions, making them staples in in vitro research. Subsequent refinements have expanded the lineup, but Good's original set remains foundational for life sciences applications.[40][42][43] Selection criteria for biological buffers emphasize attributes that prevent adverse effects on experimental systems, including a pKa value between 6.0 and 8.0 to align with most cellular pH optima, high water solubility, and low permeability through cell membranes to avoid unintended intracellular pH shifts. Additional requirements include minimal chelation of metal ions, which could disrupt enzyme cofactors; low absorbance in the ultraviolet (UV) and visible spectra (typically below 230–700 nm) to enable spectroscopic assays without interference; and chemical stability under physiological temperatures and ionic conditions. Buffers must also exhibit non-toxicity, prompting avoidance of agents like acetate in cell culture due to potential metabolic interference or cytotoxicity. These criteria ensure buffers support rather than hinder biological integrity.[40][44][45][41] Common biological buffers include several Good's variants alongside established inorganic options, each tailored to specific pH needs and experimental contexts. The following table summarizes key examples:| Buffer Name | pKa (at 20–25°C) | Effective pH Range | Notable Properties and Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane) | 8.06–8.1 | 7.0–9.0 | Temperature-sensitive (pH decreases ~0.03 units/°C); widely used in protein electrophoresis and enzyme assays due to its solubility and compatibility with biomolecules, though its basic range limits lower-pH applications.[46][47][48] |

| HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) | 7.5 | 6.8–8.2 | A Good's buffer with low UV absorbance and minimal metal chelation; ideal for cell culture and mammalian systems as it mimics physiological ionic environments without toxicity.[40][49][50] |

| Phosphate (e.g., Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4) | 7.2 (pKa2) | 5.8–8.0 | Inorganic buffer with high biocompatibility and low cost; effective in isotonic solutions for maintaining extracellular pH, though it can precipitate with divalent cations at higher concentrations.[51][52][49] |

| MOPS (3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid) | 7.2–7.28 | 6.5–7.9 | Good's buffer featuring a morpholine ring for stability; suitable for near-neutral pH in cell lysis, protein purification, and media formulation due to its low salt effects and non-interference with UV detection.[40][49][53] |

![{\displaystyle \beta =2.303\left([{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}]+{\frac {T_{\mathrm {HA} }K_{a}[{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}]}{(K_{a}+[{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}])^{2}}}+{\frac {K_{\text{w}}}{[{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}]}}\right),}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bf8b7c2c34d12f8145df3299a061593aaa76643a)

![{\displaystyle \beta \approx 2.303{\frac {T_{\mathrm {HA} }K_{a}[{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}]}{(K_{a}+[{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}])^{2}}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ec0e3ba9d065bfb822350b58e375d1f4630c6235)

![{\displaystyle K_{\text{a}}={\frac {[{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}][{\mathrm {A} {\vphantom {A}}^{-}}]}{[{\mathrm {HA} }]}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/89cb17f8ab679cc14a5d23888ed230c1a71b7384)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}C_{\mathrm {A} }&=[{\mathrm {A} {\vphantom {A}}^{3-}}]+\beta _{1}[{\mathrm {A} {\vphantom {A}}^{3-}}][{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}]+\beta _{2}[{\mathrm {A} {\vphantom {A}}^{3-}}][{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}]^{2}+\beta _{3}[{\mathrm {A} {\vphantom {A}}^{3-}}][{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}]^{3},\\C_{\mathrm {H} }&=[{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}]+\beta _{1}[{\mathrm {A} {\vphantom {A}}^{3-}}][{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}]+2\beta _{2}[{\mathrm {A} {\vphantom {A}}^{3-}}][{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}]^{2}+3\beta _{3}[{\mathrm {A} {\vphantom {A}}^{3-}}][{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}]^{3}-K_{\text{w}}[{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}]^{-1}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/611bf20542dfc1dbd8256ee6465883f1534f527a)