Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cangue

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2021) |

| Cangue | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

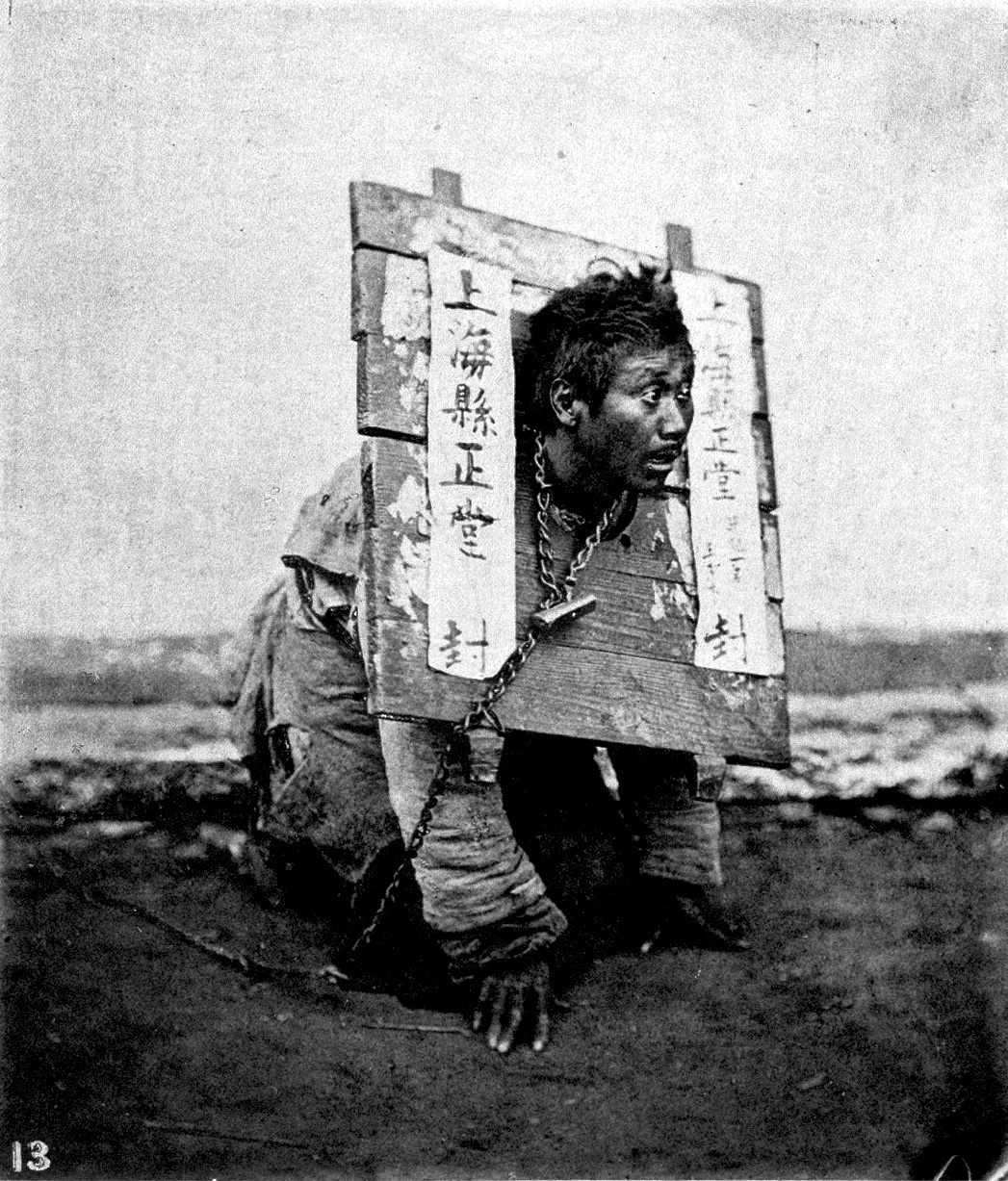

A man in a cangue in Shanghai, photographed by John Thomson c. 1870. The label reads "上海縣正堂,封," meaning "Sealed by the Shanghai County Magistrate." The offender had to rely on passersby for food. | |||||||||||||||

| Classical Chinese | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 枷 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Modern Chinese | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 木枷 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | wooden cangue | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Third alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 枷鎖 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | cangue lock | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | gông cùm | ||||||||||||||

A cangue (/kæŋ/ KANG), in Chinese referred to as a jia or tcha (Chinese: 枷), is a device that was used for public humiliation and corporal punishment in East Asia[1] and some other parts of Southeast Asia until the early years of the twentieth century. It was also occasionally used for or during torture. Because it restricted a person's movements, it was common for people wearing cangues to starve to death as they were unable to feed themselves.[2]

The word "cangue" is French, from the Portuguese "canga," which means yoke, the carrying tool has also been used to the same effect, with the hands tied to each arm of the yoke. Frequently translated as pillory, it was similar to that European punishment except that the movement of the prisoner's hands was not as rigorously restricted and that the board of the cangue was not fixed to a base and had to be carried around by the prisoner.[1]

At times, the cangue was used as a general means of restraining prisoners along with manacles and leg chains; this was true particularly of those with grave sentences or low social standing.[3]

Forms

[edit]Although there are many different forms, a typical cangue would consist of a large, heavy flat board with a hole in the center large enough for a person's neck. The board consisted of two pieces. These pieces were closed around a prisoner's neck, and then fastened shut along the edges by locks or hinges. The opening in the center was large enough for the prisoner to breathe and eat, but not large enough for a head to slip through. The prisoner was confined in the cangue for a period of time as a punishment. The size and especially weight were varied as a measure of severity of the punishment. The Great Ming Legal Code (大明律) published in 1397 specified that a cangue should be made from seasoned wood and weigh 25, 20 or 15 jīn (roughly 20–33 lb or 9–15 kg) depending on the nature of the crime involved. Often the cangue was large enough that the prisoner required assistance to eat or drink, as his hands could not reach his own mouth, or even lie down.

By the 17th century, the typical cangue had become lighter and was used primarily for public humiliation. Even so, it was intended to be worn continuously for periods as long as several months in severe cases, and a heavy cangue weighing as much as 160lbs (roughly 73 kg) could be used.[4]

Cage

[edit]The cangue would be placed on top of a cage, such that the prisoner's feet could not quite touch the ground. Supports would be placed under the feet initially, so that he would stand without pressure on the neck. Gradually, the supports would be removed, forcing the cangue to slowly strangle him.

Ritual

[edit]Historically cangues were used in rituals of penance in Chinese folk religion. These cangues either resembled the traditional wooden ones or were made out of three swords tied together or paper. Similar to its use as a torture and public humiliation device the penitent writes their sins on the board and parades themselves through the city until coming to the temple (generally a temple to the City God) and having their sins absolved. Often the cangue was then burned, especially if made of paper. The selling of ritual cangues was a major source of income for Chinese temples and continues to be one in Taiwan. The selling of fake ritual cangue by commoners was criminalized during the Qing dynasty.[5]

-

Man with head in cangue, Shanghai c. 1870–72

-

Execution after the Boxer Rebellion, China, 1900

-

Cangue worn by prisoners in 19th century Korea

-

A convict (probably a soldier) serving the cangue in Ulan Baator, Mongolia, 1913. Photo by Stephane Passet for the Archives of the Planet.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Jamyang Norbu, From Darkness to Dawn Archived 2011-06-09 at the Wayback Machine, site Phayul.com, May 19, 2009.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 182.

- ^ The T'ang Code, Volume II: Specific Articles. Translated by Johnson, Wallace. Princeton University Press. 1997. p. 404. ISBN 0-691-02579-7.

- ^ Huang, Liuhong (1984). A complete book concerning happiness and benevolence : a manual for local magistrates in seventeenth-century China. Internet Archive. Tucson, Ariz. : University of Arizona Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-8165-0820-4.

- ^ Cheung, Han (16 August 2020). "Taiwan in Time: O City God, I have sinned". Taipei Times. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cangue at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cangue at Wikimedia Commons