Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

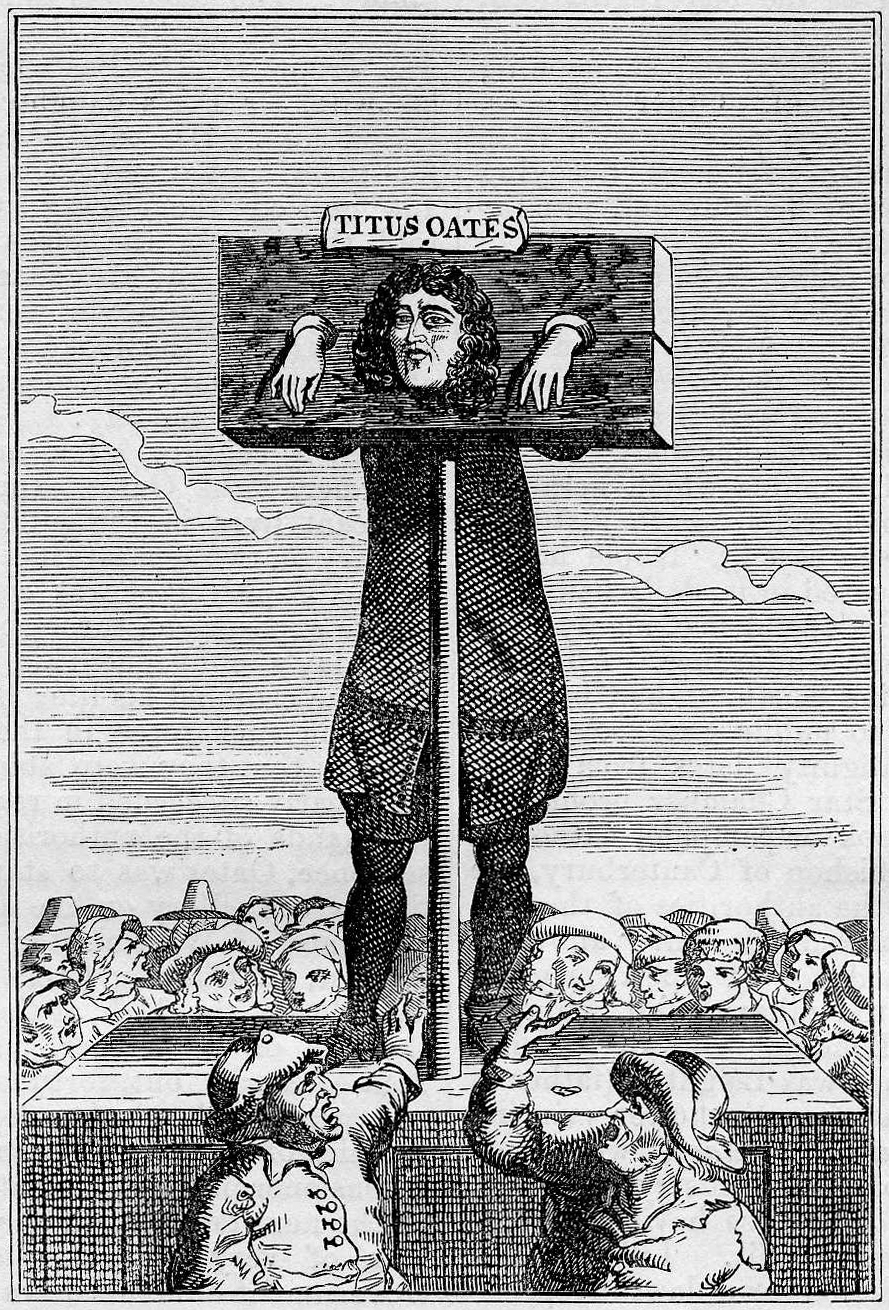

Pillory

View on Wikipedia

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, used during the medieval and renaissance periods for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse.[1] The pillory is related to the stocks.[2]

Etymology

[edit]The word is documented in English since 1274 (attested in Anglo-Latin from c. 1189), and stems from Old French pellori (1168; modern French pilori, see below), itself from medieval Latin pilloria, of uncertain origin, perhaps a diminutive of Latin pila 'pillar, stone barrier'.[3]

Description

[edit]

Rather like the lesser punishment called the stocks, the pillory consisted of hinged wooden boards forming holes through which the head or various limbs were inserted; then the boards were locked together to secure the captive. Pillories were set up to hold people in marketplaces, crossroads, and other public places.[2] They were often placed on platforms to increase public visibility of the person; often a placard detailing the crime was placed nearby.

In being forced to bend forward and stick their head and hands out in front of them, offenders in the pillory would have been extremely uncomfortable during their punishment. However, the main purpose in putting criminals in the pillory was to humiliate them publicly. On discovering that the pillory was occupied, people would excitedly gather in the marketplace to taunt, tease and laugh at the offender on display.[citation needed]

Those who gathered to watch the punishment typically wanted to make the offender's experience as unpleasant as possible. In addition to being jeered and mocked, the criminal might be pelted with rotten food, mud, offal, dead animals, and animal excrement. Sometimes people were killed or maimed in the pillory because crowds could get too violent and pelt the offender with stones, bricks and other dangerous objects.[4] However, when Daniel Defoe was sentenced to the pillory in 1703 for seditious libel, he was regarded as a hero by the crowd and was pelted with flowers.[5]

The criminal could also be sentenced to further punishments while in the pillory: humiliation by shaving off some or all hair or regular corporal punishment(s), notably flagellation or even permanent mutilation such as branding or having an ear cut off (cropping), as in the case of John Bastwick.

In Protestant cultures (such as in the Scandinavian countries), the pillory would be the worldly part of a church punishment. The delinquent would therefore first serve the ecclesiastical part of his punishment on the pillory bench in the church itself, and then be handed to the worldly authorities to be bound to the Skampåle (literally: "Shame Pole") for public humiliation.

Uses

[edit]In 1816, use of the pillory was restricted in England to punishment for perjury or subornation.[2][6] The pillory as penalty was abolished in England and Wales in 1837,[7] after Lord John Russell had said "I shall likewise propose to bring in a Bill to abolish the punishment of the pillory—a punishment which is never inflicted."[8] However, the stocks remained in use, though extremely infrequently, until 1872.[nb 1] The last person to be pilloried in England was Peter James Bossy, who was convicted of "wilful and corrupt perjury" at the Old Bailey Oyer and Terminer in 1830. He was sentenced to seven years penal transportation to Van Diemen's Land, six months in prison at Newgate and one hour in the pillory in the Old Bailey.[10][11]

In France, time in the "pilori" was usually limited to two hours. It was replaced in 1789 by "exposition", and abolished in 1832.[2] Two types of devices were used:

- The poteau (literally: "post" or "pole") was a simple post, often with a board around only the neck, and was synonymous with the mode of punishment. This was the same as the schandpaal ("shamepole") in Dutch. The carcan, an iron ring around the neck to tie a prisoner to such a post, was the name of a similar punishment that was abolished in 1832. A criminal convicted to serve time in a prison or galleys would, prior to his incarceration, be attached for two to six hours (depending on whether he was convicted to prison or the galleys) to the carcan, with his name, crime and sentence written on a board over his head.

- A permanent small tower, the upper floor of which had a ring made of wood or iron with holes for the victim's head and arms, which was often on a turntable to expose the condemned to all parts of the crowd.

Like other permanent apparatus for physical punishment, the pillory was often placed prominently and constructed more elaborately than necessary. It served as a symbol of the power of the judicial authorities, and its continual presence was seen as a deterrent, like permanent gallows for authorities endowed with high justice.

The pillory was also in common use in other western countries and colonies, and similar devices were used in other, non-Western cultures. According to one source, the pillory was abolished as a form of punishment in the United States in 1839,[2] but this cannot be entirely true because it was clearly in use in Delaware as recently as 1901.[12][13] Governor Preston Lea finally signed a bill to abolish the pillory in Delaware in March 1905.[14]

Punishment by whipping-post remained on the books in Delaware until 1972, when it became the last state to abolish it.[15] Delaware was the last state to sentence someone to whipping in 1963; however, the sentence was commuted. The last whipping in Delaware was in 1952.[16]

In Portugal today pillory has a different meaning. The Portuguese word is Pelourinho, and there are examples which are monuments of great importance, in a tradition dating back to Roman times, when criminals were chained to them.[17] They are stone columns with carved capitals, and they are usually located on the main square of the town, and/or in front of a major church or palace, or town hall: they symbolize local power and authority. Pelourinhos are considered major local monuments, several clearly bearing the coat of arms of a king or queen. The same is true of its former colonies, notably in Brazil (in its former capital, Salvador, the whole old quarter is known as Pelourinho) and Africa (e.g. Cape Verde's old capital, Cidade Velha), always as symbols of royal power. In Spain, the device was called picota.[18]

-

The pillory at Charing Cross in London, c. 1808

-

Eighteenth-century illustration of perjurer John Waller, who was killed while being pilloried in London in 1732

-

The Vere Street Coterie at the pillory in 1810

Similar humiliation devices

[edit]

There was a variant (rather of the stocks type), called a barrel pillory, or Spanish mantle, used to punish drunks, which is reported in England and among its troops. It fitted over the entire body, with the head sticking out from a hole in the top. The criminal is put in either an enclosed barrel, forcing him to kneel in his own filth, or an open barrel, also known as "barrel shirt" or "drunkards collar" after the punishable crime, leaving him to roam about town or military camp and be ridiculed and scorned.[19]

Although a pillory, by its physical nature, could double as a whipping post to tie a criminal down for public flagellation (as used to be the case in many German sentences to staupenschlag), the two as such are separate punishments: the pillory is a sentence to public humiliation, whipping is essentially a painful corporal punishment. The combination of the pillory and the whipping post was one of the various punishments the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony applied to enforce religious and intellectual conformity on the whole community.[20] Sometimes a single structure was built with separate locations for the two punishments, with a whipping post on the lower level and a pillory above (see image at right).

When permanently present in sight of prisoners, whipping posts were thought to act as a deterrent against bad behaviour, especially when each prisoner had been subjected to a "welcome beating" on arrival, as in 18th-century Waldheim in Saxony (12, 18 or 24 whip lashes on the bare posterior tied to a pole in the castle courtyard, or by birch rod over the "bock", a bench in the corner).[citation needed] Still a different penal use of such constructions is to tie the criminal down, possibly after a beating, to expose him for a long time to the elements, usually without food and drink, even to the point of starvation.[citation needed]

Finger-pillories were at one time in common use as instruments of domestic punishment. Two stout pieces of oak, the top being hinged to the bottom or fixed piece, formed when closed a number of holes sufficiently deep to admit the finger to the second joint, holding the hand imprisoned. A finger-pillory is preserved in the parish church of Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Leicestershire.[21]

Notable cases

[edit]Legacy

[edit]

While the pillory has left common use, the image remains preserved in the figurative use, which has become the dominant one, of the verb "to pillory" (attested in English since 1699),[22] meaning "to expose to public ridicule, scorn and abuse", or more generally to humiliate before witnesses.

Corresponding expressions exist in other languages, e.g., clouer au pilori "to nail to the pillory" in French, mettere alla gogna in Italian, or poner en la picota in Spanish. In Dutch it is aan de schandpaal nagelen (nailing to the pole of shame) or aan de kaak stellen, placing even greater emphasis on the predominantly humiliating character as the Dutch word for pillory, schandpaal, literally meaning "pole of shame".

See also

[edit]- Cangue, board around the head

- Judicial corporal punishment

- Jougs, metal collar

- Patibular fork

- Scold's bridle, metal frame around head, with bit to hold down tongue

- Shrew's fiddle, board around neck and wrists

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "definition: "Pillory"". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Kellaway 2003, pp. 64–65

- ^ "definitions: "Pillory" & "Stock"". Etymology Online. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ^ Cavendish, Richard (7 July 2003). "Daniel Defoe Put in the Pillory". History Today. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ Richetti, John (2008). The Cambridge Companion to Daniel Defoe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0521858403.

- ^ George Kettilby Rickards, ed. (2 July 1816). "An Act to abolish the Punishment of the Pillory, except in certain cases". The statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland [1807–1868/69]. Vol. 56. His Majesty's statute and law printers. p. 685. CAP 138. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ An Act to abolish the Punishment of the Pillory – 30 June 1837

- ^ Lord John Russell, Secretary of State for the Home Department (23 March 1837). "Criminal Law". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. col. 731.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Archived 22 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine - ^ History of pillory and stocks – A long history

- ^ Cunningham, Peter (1849). A handbook for London: Past and Present, Volume 2. J. Murray. p. 604.

- ^ "Peter James Bossy". convictrecords.com.au. Archived from the original on 26 September 2025. Retrieved 26 September 2025.

- ^ "Pilloried in Delaware; Lawbreakers Subjected to Heavy Corporal Punishment". The New York Times. 22 September 1901. p. 3. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ "Five men whipped by Sheriff; Another Exhibition of Corporal Punishment in Delaware". The New York Times. 17 February 1901. p. 1. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Wash.). "Has Abolished The Pillory" Archived 12 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. 22 March 1905, p. 6. Retrieved on 2 October 2013.

- ^ 1973 World Almanac and Book of Facts p. 90.

- ^ Cohen, Celia (November 2013). "Whipping Post No Longer An Acceptable Form of Criminal Punishment". Delaware Today. Today Media. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ de Macedo, Joaquim Antonio (1874). A guide to Lisbon and its Environs including Cintra and Mafra with a large plan of Lisbon. p. 110.

- ^ de Quirós, C. Bernaldo (1907). La Picota – Crímenes y castigos en el país castellano en los tiempos medios. Madrid: Librería General de Victoriano Suárez. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021.

- ^ Images of barrels and other stocks as used in imperial China Archived 16 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Merrill, Louis Taylor (1945). "The Puritan Policeman". American Sociological Review. 10 (6). American Sociological Association: 766–776. doi:10.2307/2085847. JSTOR 2085847.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 610.

- ^ Richard Bentley, Dissertation on the Epistles of Phalaris; cited in the Oxford English Dictionary

General and cited references

[edit]- Beadle, Jeremy; Harrison, Ian (2007). Firsts, Lasts & Onlys: Crime. Robson Books. ISBN 978-1-905798-04-9.

- Kellaway, Jean (2003). The History of Torture and Execution. Pequot Press. ISBN 978-1-904668-03-9.

External links

[edit]- Examples of Pillories from the UK and Ireland on geograph.org.uk

- Debate in the House of Commons on the Pillory Abolition Bill, 6 April 1815

- Debate in the House of Lords on the Pillory Abolition Bill, 5 July 1815 and 10 July 1815

- Debate in the House of Commons on the Pillory Abolition Bill, 22 February 1816

- Debate in the House of Lords on the Pillory Abolition Bill, 26 February 1816