Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Floor and ceiling functions

View on Wikipedia

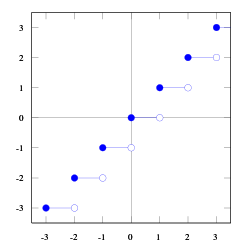

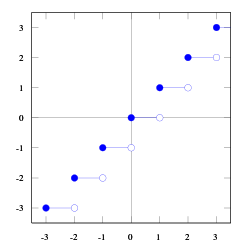

In mathematics, the floor function is the function that takes as input a real number x, and gives as output the greatest integer less than or equal to x, denoted ⌊x⌋ or floor(x). Similarly, the ceiling function maps x to the least integer greater than or equal to x, denoted ⌈x⌉ or ceil(x).[1]

For example, for floor: ⌊2.4⌋ = 2, ⌊−2.4⌋ = −3, and for ceiling: ⌈2.4⌉ = 3, and ⌈−2.4⌉ = −2.

The floor of x is also called the integral part, integer part, greatest integer, or entier of x, and was historically denoted [x] (among other notations).[2] However, the same term, integer part, is also used for truncation towards zero, which differs from the floor function for negative numbers.

For an integer n, ⌊n⌋ = ⌈n⌉ = n.

Although floor(x + 1) and ceil(x) produce graphs that appear exactly alike, they are not the same when the value of x is an exact integer. For example, when x = 2.0001, ⌊2.0001 + 1⌋ = ⌈2.0001⌉ = 3. However, if x = 2, then ⌊2 + 1⌋ = 3, while ⌈2⌉ = 2.

| x | Floor ⌊x⌋ | Ceiling ⌈x⌉ | Fractional part {x} |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 2.0001 | 2 | 3 | 0.0001 |

| 2.4 | 2 | 3 | 0.4 |

| 2.9 | 2 | 3 | 0.9 |

| 2.999 | 2 | 3 | 0.999 |

| −2.7 | −3 | −2 | 0.3 |

| −2 | −2 | −2 | 0 |

Notation

[edit]The integral part or integer part of a number (partie entière in the original) was first defined in 1798 by Adrien-Marie Legendre in his proof of the Legendre's formula.

Carl Friedrich Gauss introduced the square bracket notation [x] in his third proof of quadratic reciprocity (1808).[3] This remained the standard[4] in mathematics until Kenneth E. Iverson introduced, in his 1962 book A Programming Language, the names "floor" and "ceiling" and the corresponding notations ⌊x⌋ and ⌈x⌉.[5][6] (Iverson used square brackets for a different purpose, the Iverson bracket notation.) Both notations are now used in mathematics, although Iverson's notation will be followed in this article.

In some sources, boldface or double brackets ⟦x⟧ are used for floor, and reversed brackets ⟧x⟦ or ]x[ for ceiling.[7][8]

The fractional part is the sawtooth function, denoted by {x} for real x and defined by the formula

- {x} = x − ⌊x⌋[9]

For all x,

- 0 ≤ {x} < 1.

These characters are provided in Unicode:

- U+2308 ⌈ LEFT CEILING (⌈, ⌈)

- U+2309 ⌉ RIGHT CEILING (⌉, ⌉)

- U+230A ⌊ LEFT FLOOR (⌊, ⌊)

- U+230B ⌋ RIGHT FLOOR (⌋, ⌋)

In the LaTeX typesetting system, these symbols can be specified with the \lceil, \rceil, \lfloor, and \rfloor commands in math mode. LaTeX has supported UTF-8 since 2018, so the Unicode characters can now be used directly.[10] Larger versions are\left\lceil, \right\rceil, \left\lfloor, and \right\rfloor.

Definition and properties

[edit]Given real numbers x and y, integers m and n and the set of integers , floor and ceiling may be defined by the equations

Since there is exactly one integer in a half-open interval of length one, for any real number x, there are unique integers m and n satisfying the equation

where and may also be taken as the definition of floor and ceiling.

Equivalences

[edit]These formulas can be used to simplify expressions involving floors and ceilings.[11]

In the language of order theory, the floor function is a residuated mapping, that is, part of a Galois connection: it is the upper adjoint of the function that embeds the integers into the reals.

These formulas show how adding an integer n to the arguments affects the functions:

The above are never true if n is not an integer; however, for every x and y, the following inequalities hold:

Monotonicity

[edit]Both floor and ceiling functions are monotonically non-decreasing functions:

Relations among the functions

[edit]It is clear from the definitions that

- with equality if and only if x is an integer, i.e.

In fact, for integers n, both floor and ceiling functions are the identity:

Negating the argument switches floor and ceiling and changes the sign:

and:

Negating the argument complements the fractional part:

The floor, ceiling, and fractional part functions are idempotent:

The result of nested floor or ceiling functions is the innermost function:

due to the identity property for integers.

Quotients

[edit]If m and n are integers and n ≠ 0,

If n is positive[12]

If m is positive[13]

For m = 2 these imply

More generally,[14] for positive m (See Hermite's identity)

The following can be used to convert floors to ceilings and vice versa (with m being positive)[15]

For all m and n strictly positive integers:[16]

which, for positive and coprime m and n, reduces to

and similarly for the ceiling and fractional part functions (still for positive and coprime m and n),

Since the right-hand side of the general case is symmetrical in m and n, this implies that

More generally, if m and n are positive,

This is sometimes called a reciprocity law.[17]

Division by positive integers gives rise to an interesting and sometimes useful property. Assuming ,

Similarly,

Indeed,

keeping in mind that The second equivalence involving the ceiling function can be proved similarly.

For d being a positive integer with x greater than d. Then [18]

where is the remainder of dividing by d

Nested divisions

[edit]For a positive integer n, and arbitrary real numbers m and x:[19]

Continuity and series expansions

[edit]None of the functions discussed in this article are continuous, but all are piecewise linear: the functions , , and have discontinuities at the integers.

is upper semi-continuous and and are lower semi-continuous.

Since none of the functions discussed in this article are continuous, none of them have a power series expansion. Since floor and ceiling are not periodic, they do not have uniformly convergent Fourier series expansions. The fractional part function has Fourier series expansion[20] for x not an integer.

At points of discontinuity, a Fourier series converges to a value that is the average of its limits on the left and the right, unlike the floor, ceiling and fractional part functions: for y fixed and x a multiple of y the Fourier series given converges to y/2, rather than to x mod y = 0. At points of continuity the series converges to the true value.

Using the formula gives for x not an integer.

Applications

[edit]Mod operator

[edit]For an integer x and a positive integer y, the modulo operation, denoted by x mod y, gives the value of the remainder when x is divided by y. This definition can be extended to real x and y, y ≠ 0, by the formula

Then it follows from the definition of floor function that this extended operation satisfies many natural properties. Notably, x mod y is always between 0 and y, i.e.,

if y is positive,

and if y is negative,

Quadratic reciprocity

[edit]Gauss's third proof of quadratic reciprocity, as modified by Eisenstein, has two basic steps.[21][22]

Let p and q be distinct positive odd prime numbers, and let

First, Gauss's lemma is used to show that the Legendre symbols are given by

The second step is to use a geometric argument to show that

Combining these formulas gives quadratic reciprocity in the form

There are formulas that use floor to express the quadratic character of small numbers mod odd primes p:[23]

Rounding

[edit]For an arbitrary real number , rounding to the nearest integer with tie breaking towards positive infinity is given by

rounding towards negative infinity is given as

If tie-breaking is away from 0, then the rounding function is

(where is the sign function), and rounding towards even can be expressed with the more cumbersome

which is the above expression for rounding towards positive infinity minus an integrality indicator for .

Rounding a real number to the nearest integer value forms a very basic type of quantizer – a uniform one. A typical (mid-tread) uniform quantizer with a quantization step size equal to some value can be expressed as

- ,

Number of digits

[edit]The number of digits in base b of a positive integer k is

Number of strings without repeated characters

[edit]The number of possible strings of arbitrary length that doesn't use any character twice is given by[24][better source needed]

where:

- n > 0 is the number of letters in the alphabet (e.g., 26 in English)

- the falling factorial denotes the number of strings of length k that don't use any character twice.

- n! denotes the factorial of n

- e = 2.718... is Euler's number

For n = 26, this comes out to 1096259850353149530222034277.

Factors of factorials

[edit]Let n be a positive integer and p a positive prime number. The exponent of the highest power of p that divides n! is given by a version of Legendre's formula[25]

where is the way of writing n in base p. This is a finite sum, since the floors are zero when pk > n.

Beatty sequence

[edit]The Beatty sequence shows how every positive irrational number gives rise to a partition of the natural numbers into two sequences via the floor function.[26]

Euler's constant (γ)

[edit]There are formulas for Euler's constant γ = 0.57721 56649 ... that involve the floor and ceiling, e.g.[27]

and

Riemann zeta function (ζ)

[edit]The fractional part function also shows up in integral representations of the Riemann zeta function. It is straightforward to prove (using integration by parts)[28] that if is any function with a continuous derivative in the closed interval [a, b],

Letting for real part of s greater than 1 and letting a and b be integers, and letting b approach infinity gives

This formula is valid for all s with real part greater than −1, (except s = 1, where there is a pole) and combined with the Fourier expansion for {x} can be used to extend the zeta function to the entire complex plane and to prove its functional equation.[29]

For s = σ + it in the critical strip 0 < σ < 1,

In 1947 van der Pol used this representation to construct an analogue computer for finding roots of the zeta function.[30]

Formulas for prime numbers

[edit]The floor function appears in several formulas characterizing prime numbers. For example, since it follows that a positive integer n is a prime if and only if[31]

One may also give formulas for producing the prime numbers. For example, let pn be the n-th prime, and for any integer r > 1, define the real number α by the sum

Then[32]

A similar result is that there is a number θ = 1.3064... (Mills' constant) with the property that

are all prime.[33]

There is also a number ω = 1.9287800... with the property that

are all prime.[33]

Let π(x) be the number of primes less than or equal to x. It is a straightforward deduction from Wilson's theorem that[34]

Also, if n ≥ 2,[35]

None of the formulas in this section are of any practical use.[36][37]

Solved problems

[edit]Ramanujan submitted these problems to the Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society.[38]

If n is a positive integer, prove that

Some generalizations to the above floor function identities have been proven.[39]

Unsolved problem

[edit]The study of Waring's problem has led to an unsolved problem:

Are there any positive integers k ≥ 6 such that[40]

Mahler has proved there can only be a finite number of such k; none are known.[41]

Computer implementations

[edit]

int function from floating-point conversion in CIn most programming languages, the simplest method to convert a floating point number to an integer does not do floor or ceiling, but truncation. The reason for this is historical, as the first machines used ones' complement and truncation was simpler to implement (floor is simpler in two's complement). FORTRAN was defined to require this behavior and thus almost all processors implement conversion this way. Some consider this to be an unfortunate historical design decision that has led to bugs handling negative offsets and graphics on the negative side of the origin.[citation needed]

An arithmetic right-shift of a signed integer by is the same as . Division by a power of 2 is often written as a right-shift, not for optimization as might be assumed, but because the floor of negative results is required. Assuming such shifts are "premature optimization" and replacing them with division can break software.[citation needed]

Many programming languages (including C, C++,[42][43] C#,[44][45] Java,[46][47]

Julia,[48]

PHP,[49][50] R,[51] and Python[52]) provide standard functions for floor and ceiling, usually called floor and ceil, or less commonly ceiling.[53] The language APL uses ⌊x for floor. The J Programming Language, a follow-on to APL that is designed to use standard keyboard symbols, uses <. for floor and >. for ceiling.[54]

ALGOL usesentier for floor.

In Microsoft Excel the function INT rounds down rather than toward zero,[55] while FLOOR rounds toward zero, the opposite of what "int" and "floor" do in other languages. Since 2010 FLOOR has been changed to error if the number is negative.[56] The OpenDocument file format, as used by OpenOffice.org, Libreoffice and others, INT[57] and FLOOR both do floor, and FLOOR has a third argument to reproduce Excel's earlier behavior.[58]

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Graham, Knuth, & Patashnik, Ch. 3.1

- ^

1) Luke Heaton, A Brief History of Mathematical Thought, 2015, ISBN 1472117158 (n.p.)

2) Albert A. Blank et al., Calculus: Differential Calculus, 1968, p. 259

3) John W. Warris, Horst Stocker, Handbook of mathematics and computational science, 1998, ISBN 0387947469, p. 151 - ^ Lemmermeyer, pp. 10, 23.

- ^ e.g. Cassels, Hardy & Wright, and Ribenboim use Gauss's notation. Graham, Knuth & Patashnik, and Crandall & Pomerance use Iverson's.

- ^ Iverson, p. 12.

- ^ Higham, p. 25.

- ^ Mathwords: Floor Function.

- ^ Mathwords: Ceiling Function

- ^ Graham, Knuth, & Patashnik, p. 70.

- ^ "LaTeX News, Issue 28" (PDF; 379 KB). The LaTeX Project. April 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Graham, Knuth, & Patashink, Ch. 3

- ^ Graham, Knuth, & Patashnik, p. 73

- ^ Graham, Knuth, & Patashnik, p. 85

- ^ Graham, Knuth, & Patashnik, p. 85 and Ex. 3.15

- ^ Graham, Knuth, & Patashnik, Ex. 3.12

- ^ Graham, Knuth, & Patashnik, p. 94.

- ^ Graham, Knuth, & Patashnik, p. 94

- ^ Problems and Solutions, The College Mathematics Journal, 56:4

- ^ Graham, Knuth, & Patashnik, p. 71, apply theorem 3.10 with x/m as input and the division by n as function

- ^ Titchmarsh, p. 15, Eq. 2.1.7

- ^ Lemmermeyer, § 1.4, Ex. 1.32–1.33

- ^ Hardy & Wright, §§ 6.11–6.13

- ^ Lemmermeyer, p. 25

- ^ OEIS sequence A000522 (Total number of arrangements of a set with n elements: a(n) = Sum_{k=0..n} n!/k!.) (See Formulas.)

- ^ Hardy & Wright, Th. 416

- ^ Graham, Knuth, & Patashnik, pp. 77–78

- ^ These formulas are from the Wikipedia article Euler's constant, which has many more.

- ^ Titchmarsh, p. 13

- ^ Titchmarsh, pp.14–15

- ^ Crandall & Pomerance, p. 391

- ^ Crandall & Pomerance, Ex. 1.3, p. 46. The infinite upper limit of the sum can be replaced with n. An equivalent condition is n > 1 is prime if and only if

- ^ Hardy & Wright, § 22.3

- ^ a b Ribenboim, p. 186

- ^ Ribenboim, p. 181

- ^ Crandall & Pomerance, Ex. 1.4, p. 46

- ^ Ribenboim, p. 180 says that "Despite the nil practical value of the formulas ... [they] may have some relevance to logicians who wish to understand clearly how various parts of arithmetic may be deduced from different axiomatzations ... "

- ^ Hardy & Wright, pp. 344—345 "Any one of these formulas (or any similar one) would attain a different status if the exact value of the number α ... could be expressed independently of the primes. There seems no likelihood of this, but it cannot be ruled out as entirely impossible."

- ^ Ramanujan, Question 723, Papers p. 332

- ^ Somu, Sai Teja; Kukla, Andrzej (2022). "On some generalizations to floor function identities of Ramanujan" (PDF). Integers. 22. arXiv:2109.03680.

- ^ Hardy & Wright, p. 337

- ^ Mahler, Kurt (1957). "On the fractional parts of the powers of a rational number II". Mathematika. 4 (2): 122–124. doi:10.1112/S0025579300001170.

- ^ "C++ reference of

floorfunction". Retrieved 5 December 2010. - ^ "C++ reference of

ceilfunction". Retrieved 5 December 2010. - ^ dotnet-bot. "Math.Floor Method (System)". docs.microsoft.com. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ dotnet-bot. "Math.Ceiling Method (System)". docs.microsoft.com. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "Math (Java SE 9 & JDK 9 )". docs.oracle.com. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ "Math (Java SE 9 & JDK 9 )". docs.oracle.com. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ "Math (Julia v1.10)". docs.julialang.org/en/v1/. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "PHP manual for

ceilfunction". Retrieved 18 July 2013. - ^ "PHP manual for

floorfunction". Retrieved 18 July 2013. - ^ "R: Rounding of Numbers".

- ^ "Python manual for

mathmodule". Retrieved 18 July 2013. - ^ Sullivan, p. 86.

- ^ "Vocabulary". J Language. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ "INT function". Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ "FLOOR function". Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ "Documentation/How Tos/Calc: INT function". Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ "Documentation/How Tos/Calc: FLOOR function". Retrieved 29 October 2021.

References

[edit]- J.W.S. Cassels (1957), An introduction to Diophantine approximation, Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics and Mathematical Physics, vol. 45, Cambridge University Press

- Crandall, Richard; Pomerance, Carl (2001), Prime Numbers: A Computational Perspective, New York: Springer, ISBN 0-387-94777-9

- Graham, Ronald L.; Knuth, Donald E.; Patashnik, Oren (1994), Concrete Mathematics, Reading Ma.: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-55802-5

- Hardy, G. H.; Wright, E. M. (1980), An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (Fifth edition), Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-853171-5

- Nicholas J. Higham, Handbook of writing for the mathematical sciences, SIAM. ISBN 0-89871-420-6, p. 25

- ISO/IEC. ISO/IEC 9899::1999(E): Programming languages — C (2nd ed), 1999; Section 6.3.1.4, p. 43.

- Iverson, Kenneth E. (1962), A Programming Language, Wiley

- Lemmermeyer, Franz (2000), Reciprocity Laws: from Euler to Eisenstein, Berlin: Springer, ISBN 3-540-66957-4

- Ramanujan, Srinivasa (2000), Collected Papers, Providence RI: AMS / Chelsea, ISBN 978-0-8218-2076-6

- Ribenboim, Paulo (1996), The New Book of Prime Number Records, New York: Springer, ISBN 0-387-94457-5

- Michael Sullivan. Precalculus, 8th edition, p. 86

- Titchmarsh, Edward Charles; Heath-Brown, David Rodney ("Roger") (1986), The Theory of the Riemann Zeta-function (2nd ed.), Oxford: Oxford U. P., ISBN 0-19-853369-1

External links

[edit]- "Floor function", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Štefan Porubský, "Integer rounding functions" Archived 23 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Interactive Information Portal for Algorithmic Mathematics, Institute of Computer Science of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic, retrieved 24 October 2008

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Floor Function". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Ceiling Function". MathWorld.

Floor and ceiling functions

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Notation

The standard notation for the floor function, which returns the greatest integer less than or equal to a real number , is , employing the left-pointing floor brackets. Similarly, the ceiling function, which returns the smallest integer greater than or equal to , is denoted , using right-pointing ceiling brackets. These notations, along with the terms "floor" and "ceiling," were introduced by computer scientist Kenneth E. Iverson in his 1962 book A Programming Language.[5][6] Prior to Iverson's proposal, the floor function was commonly denoted by square brackets as $$, a convention originating with Carl Friedrich Gauss in his 1808 demonstration of quadratic reciprocity. However, this notation proved ambiguous, as square brackets were also used for closed intervals in mathematical analysis. To resolve such conflicts, Iverson advocated the distinct floor and ceiling brackets, which have since become the prevailing standard in mathematics.[5][6] Alternative notations persist in certain contexts. The square bracket $$ endures in some older mathematical literature for the greatest integer function, though its use is discouraged due to the aforementioned ambiguity. In computational settings, the functions are often expressed as for truncation toward zero (which coincides with floor for positive ) or explicitly as and in programming languages such as C++, Python, and MATLAB.[7][6]Definitions

The floor function, denoted , is defined for any real number as the greatest integer such that , or equivalently .[5] This characterization ensures that is the unique integer bounding from below in the set of integers.[5] The ceiling function, denoted , is defined for any real number as the least integer such that , or equivalently .[8] This provides the unique integer bounding from above within the integers.[8] When is itself an integer, both functions coincide with the input: .[5][8] Although the floor and ceiling functions are primarily defined over the real numbers, extensions to the complex domain have been proposed, typically by applying the functions componentwise to the real and imaginary parts, such as for ; however, the real case remains the standard focus.[9][5] Graphically, both the floor and ceiling functions are step functions over the reals, constant on intervals for integers , with both jumping upward at each integer, forming staircase-like patterns when plotted.[5][8]Basic Properties

The floor function, denoted ⌊x⌋, maps any real number x to the greatest integer less than or equal to x, ensuring that its output is always an integer.[5] Similarly, the ceiling function, denoted ⌈x⌉, maps x to the smallest integer greater than or equal to x, which is also always an integer.[8] As x varies over all real numbers, the range of both the floor and ceiling functions is the set of all integers; for any integer n, there exist real numbers x such that ⌊x⌋ = n and ⌈x⌉ = n.[5][8] These functions satisfy the following bounding inequalities for any real x:x - 1 < ⌊x⌋ ≤ x ≤ ⌈x⌉ < x + 1.

These relations follow directly from the definitions, with ⌊x⌋ ≤ x < ⌊x⌋ + 1 and ⌈x⌉ - 1 < x ≤ ⌈x⌉.[10] If x is not an integer, then ⌈x⌉ = ⌊x⌋ + 1.[8] Consequently, ⌊x⌋ and ⌈x⌉ are consecutive integers and thus have opposite parity—one even and one odd.[5][8]

Advanced Properties

Equivalences and Identities

One fundamental identity relating the ceiling and floor functions is for all real numbers .[11] This equivalence arises from the definitional properties of the functions: the floor is the greatest integer less than or equal to , while the ceiling is the least integer greater than or equal to . To sketch the proof, let , so . Multiplying through by reverses the inequalities, yielding , or equivalently, . Therefore, the least integer greater than or equal to is , confirming .[1] The ceiling function can also be expressed directly in terms of the floor function based on whether is an integer: if is not an integer, then ; if is an integer, then .[1] This follows from the definitions, as for non-integer , , so the smallest integer exceeding that is at least is ; for integer , both functions return itself. A proof sketch uses the bounding property: let , so . If , then ; otherwise, , so . The fractional part of a real number , denoted , provides another key equivalence: , where .[11] This identity captures the non-integer remainder after removing the greatest integer less than or equal to . By definition, since , subtracting yields , directly establishing the bounds and the expression. Variants of the integer part include approximations to the nearest integer function, which rounds to the closest integer. For positive , one common expression is , but this has limitations: it fails to handle ties consistently at half-integers (e.g., when is an integer, such as , where equidistance to 1 and 2 requires a specified tie-breaking rule, often rounding away from zero or to even).[12] A proof sketch for its validity when proceeds as follows: let be the nearest integer to , so or with appropriate tie resolution. Then if no tie, implying ; ties violate this strict inequality, highlighting the limitation.Monotonicity and Continuity

The floor function and the ceiling function are both non-decreasing over the real numbers, meaning that for any , it holds that and .[13] This monotonicity follows directly from their definitions as the greatest integer less than or equal to and the least integer greater than or equal to , respectively, ensuring that as increases, the output either remains constant or jumps to the next integer. Between consecutive integers, specifically on intervals for the floor function and for the ceiling function where is an integer, each function is constant, reflecting its step-like behavior.[5][8] Both functions exhibit jump discontinuities at every integer point, where the function value shifts abruptly by 1, but they are continuous at all non-integer points. For the floor function, the left-hand limit at an integer is , while the right-hand limit is , matching , which establishes right-continuity at integers.[14] In contrast, the ceiling function is left-continuous at integers, with and . At non-integers , both one-sided limits equal the function value, confirming continuity there.[13] These properties highlight the piecewise constant nature of the functions, with monotonicity preserved globally despite the discontinuities confined to the integers. The right-continuity of the floor function and left-continuity of the ceiling function align with their roles in bounding real numbers from below and above, respectively, and are upper and lower semicontinuous accordingly.[13]Relations Between Floor and Ceiling

One fundamental relation between the floor function and the ceiling function is their difference, which indicates whether is an integer. Specifically, if is an integer, and otherwise.[1] This follows from the definitions: when is an integer, both functions return ; when is not an integer, is the next integer above . For example, if , then and , so the difference is 1; if , both are 4, so the difference is 0. The sum of the floor and ceiling functions provides another key interconnection. If is an integer, then ; otherwise, .[1] This identity derives directly from the difference relation above, as the sum can be rewritten using . For instance, with , the sum is ; for , it is . Compositional relations highlight the idempotent nature of these functions. Applying the floor function to the ceiling yields , since is always an integer and the floor of an integer is itself.[1] Similarly, , as is an integer and the ceiling of an integer is itself. These hold for all real , demonstrating that each function is the identity when composed with the other on its output. A symmetry relation appears in the average of the floor and ceiling values, particularly for half-integers. The expression equals if is an integer, and otherwise, providing a midpoint between the bounding integers.[1] For half-integers like (where is an integer), this average is exactly , and it relates to the rounding operation , which equals in such cases, offering a symmetric view around the half-point. For example, with , , , average = 2.5, and .Series Expansions

The floor function admits an analytic representation via the Fourier series of its periodic sawtooth counterpart, providing a useful infinite series expansion for approximation purposes. For any non-integer real number , This expansion holds pointwise and derives from the orthogonality of sine functions over one period, capturing the discontinuous jumps at integers through the harmonic terms.[15] Equivalently, the expression can be framed in terms of the fractional part , which satisfies for non-integer . This series for the fractional part connects directly to the first periodic Bernoulli polynomial , defined as the period-1 extension of the Bernoulli polynomial on . The Fourier series of is precisely , yielding . Higher-degree periodic Bernoulli polynomials provide analogous but more complex series for related step-like functions, though the degree-1 case suffices for the floor function.[16] A similar expansion applies to the ceiling function via , substituting into the floor series to obtain for non-integer .[17] The convergence of these series is uniform on any compact interval excluding integers, where the functions exhibit continuity within each interval. Near integers, the partial sums converge pointwise to the function value but more slowly, with asymptotic behavior dominated by the Gibbs phenomenon, where overshoots approach approximately 8.9% of the discontinuity jump size before settling. This makes the series particularly effective for approximations away from lattice points.Operations Involving Floor and Ceiling

Quotients and Divisions

The integer quotient of two positive integers and is defined as , which gives the largest integer such that . This operation discards the fractional part of the real division , effectively performing truncation toward zero for positive values. For example, , since and .[18] The division algorithm in number theory relies on the floor function to express any positive integer in terms of a positive divisor : , where is the remainder satisfying . This decomposition is unique and forms the basis for many algorithmic processes, such as the Euclidean algorithm for computing greatest common divisors. The quotient thus captures the complete multiples of fitting into . A key inequality involving quotients arises when considering sums: for positive real numbers and positive integer , This subadditivity property follows from the general behavior of the floor function on sums, where the fractional parts may or may not cause a carry-over of 1. For instance, with , , , , and , satisfying . The upper bound is tight when the fractional parts sum to less than 1, and the lower bound holds due to the non-negativity of fractional parts. For ceiling quotients, an equivalent expression using the floor function is useful in computations avoiding direct ceiling operations: for positive integers , This identity adjusts the numerator to account for the smallest integer exceeding or equaling by effectively rounding up via the floor. For example, , and . It is particularly valuable in integer arithmetic for tasks like array sizing or pagination.Nested Functions

Nested applications of the floor function often arise in algorithms that simulate division processes, such as the Euclidean algorithm for computing the greatest common divisor of two integers. In this context, the algorithm iteratively applies the floor operation to determine quotients: given integers and with , it computes , leading to a nested structure of floors that terminates when the remainder is zero.[19] This nesting mirrors the finite continued fraction expansion of the rational , where each partial quotient is a floor value derived from successive divisions.[19] Continued fraction expansions provide a canonical example of nested floor functions for real numbers greater than 1. For a real number , the simple continued fraction is defined recursively as , where is the integer part, and , with subsequent terms and for .[19] This process generates an infinite sequence of integers for irrational , or a finite one for rational , effectively nesting floors through the iterative inversion and truncation. The expansion converges to via the convergents , which satisfy .[19] In number theory, nested floors appear in approximations related to Pell equations, particularly through continued fractions of quadratic irrationals like for nonsquare integer . The partial quotients are generated recursively via the continued fraction algorithm and form a periodic expansion. The convergents satisfy , with solutions to the Pell equation emerging from convergents at the end of each period. For instance, the initial floor initiates the recursion that yields these fundamental solutions efficiently, as utilized in methods like the Chakravala algorithm, avoiding exhaustive search.[19]Modulo Operation

The modulo operation for a real number and a positive integer is defined using the floor function as This expression represents the remainder after dividing by , and it generalizes the standard integer modulo to real numbers. A key property of this definition is that holds for all real and positive integer , ensuring the remainder is nonnegative and less than the modulus. Additionally, the modulo function is periodic with period , satisfying for any integer . The modulo operation relates to the fractional part function , which always lies in , through the identity This connection highlights how the floor function captures the integer quotient, leaving the scaled fractional part as the remainder. For negative values of , the floor-based definition naturally produces a nonnegative remainder in . However, in certain computational or alternative conventions, adjustments using the ceiling function may be applied, such as , which can yield a different nonnegative value less than depending on the context.[20]Applications in Number Theory

Quadratic Reciprocity

The law of quadratic reciprocity relates the Legendre symbols and for distinct odd primes and , stating that Here, the floor function appears in the exponent to compute the integer parts and , which determine the sign flip based on the quadratic characters of the primes modulo 4. This formulation highlights the floor function's role in capturing the parity of these halved integers, essential since or yields no sign change, while both congruent to 3 modulo 4 does.[21] In proofs of this law, the floor function facilitates exponent computation, particularly in Gauss's lemma, which underpins many derivations. Gauss's lemma expresses the Legendre symbol as , where counts the number of negative least residues among modulo , and for odd coprime to odd prime . This sum of floor values modulo 2 directly yields the exponent in reciprocity, linking the symbols through parity arguments on lattice points or residue counts. Historically, Carl Friedrich Gauss introduced the floor function (denoted by square brackets for the greatest integer less than or equal to ) in his third proof of quadratic reciprocity in 1808, as part of his efforts to rigorously handle integer divisions in the Disquisitiones Arithmeticae supplements, marking an early systematic use of this notation in number theory.[21][22][23] This involvement extends to generalizations via the Jacobi symbol, which generalizes the Legendre symbol to odd composite denominators. For coprime odd positive integers and , the Jacobi symbol satisfies with the floor function again in the exponent to ensure integer evaluation, as the symbol decomposes multiplicatively over the prime factors of . Introduced by Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi in 1837, this extension preserves reciprocity properties, enabling efficient computation of Legendre symbols through Euclidean-like algorithms while using floor-based exponents for the sign.[24]Beatty Sequences

A Beatty sequence is the sequence of integers given by for positive integers , where is an irrational number.[25] These sequences are strictly increasing due to the monotonicity of the floor function and the fact that , ensuring .[25] Beatty's theorem asserts that if and are irrational numbers satisfying , then the Beatty sequences and partition the set of positive integers: every positive integer appears in exactly one of the two sequences, with no overlaps or omissions.[26] The theorem, first established by Lord Rayleigh in 1894 and popularized through a problem posed by Samuel Beatty in 1926, highlights the partitioning power of the floor function when applied to irrationals related in this specific reciprocal manner.[27] A well-known example arises with the golden ratio , which satisfies since and .[28] The sequence for begins 1, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, ..., known as the lower Wythoff sequence, while the complementary sequence for is 2, 5, 7, 10, 13, 15, ....[25] These sequences are Fibonacci-related, as the terms of the lower Wythoff sequence can be expressed using Fibonacci numbers , specifically , though more directly, they represent positions of 1's in the Zeckendorf representation of integers.[28] The proof of Beatty's theorem leverages the irrationality of and alongside floor function properties to establish disjointness and completeness. To show disjointness, assume for some positive integers ; this implies and , so . Substituting yields with , leading to a rational approximation that contradicts the irrationality of unless , which is impossible for distinct sequences.[26] For completeness, consider the number of terms not exceeding some large integer : the count in the first sequence is and in the second is . Using the floor inequality , their sum satisfies , and given , the sum equals exactly . Advancing to adds precisely one new term, ensuring all integers are covered without gaps.[26]Prime Number Formulas

The floor function plays a role in several explicit formulas and approximations related to prime numbers, particularly in expressions for the nth prime and the prime-counting function. One notable example is Willans' formula, which provides an exact, albeit highly inefficient, closed-form expression for the nth prime number using nested floor functions and summations. This formula leverages Wilson's theorem, which states that for a prime , , or equivalently, if is prime and 0 otherwise for . The inner sum counts the number of primes up to , and the outer structure isolates through a summation up to , ensuring exactness but with exponential computational complexity.[29] The formula is given by This construction, while theoretically elegant, requires evaluating factorials up to enormous sizes, rendering it impractical for even moderate . It was introduced in a 1964 paper by C. R. Willans as an illustration of how floor functions can encode primality tests into summatory expressions.[29] In the context of prime-counting approximations, Riemann's explicit formula for the prime-power counting function incorporates the floor function to bound the summation over roots of unity. Defined as , where the sum is over primes and positive integers , it expands as with denoting the number of primes up to . This form arises from Möbius inversion applied to the von Mangoldt function and highlights the floor's role in truncating the sum based on the logarithmic scale of . The full Riemann-von Mangoldt explicit formula further relates to the zeros of the Riemann zeta function, providing asymptotic insights into prime distribution, though the floor term ensures the expression remains finite for finite .[30] Chebyshev's bias, an observed skew in the distribution of primes among residue classes, can be analyzed using the floor of the logarithm to group primes by their approximate magnitude. Specifically, categorizes primes into intervals , allowing examination of the bias—such as the tendency for more primes congruent to 3 modulo 4 than to 1 modulo 4 up to —across logarithmic scales. This grouping reveals that the bias persists due to contributions from small primes and logarithmic densities in L-functions associated with Dirichlet characters, with the floor enabling precise dyadic decomposition in summations like , where is a non-principal character. First noted by Chebyshev in 1853, this phenomenon is quantified through differences in Chebyshev functions , and the floor-log partitioning underscores the scale-dependent nature of the imbalance.[31] Despite their theoretical value, these floor-involving formulas for primes suffer from severe computational limitations. Willans' formula, for instance, demands time exponential in , making it unusable beyond tiny values like (yielding ). Similarly, while Riemann's formula offers profound asymptotic accuracy, evaluating the floor-bounded sum requires knowledge of zeta zeros, which grows computationally intensive for large , and practical prime enumeration relies on sieves rather than such expressions. Analyses of Chebyshev's bias via floor-log groupings, though insightful for understanding distributional irregularities, do not yield efficient generation methods and instead inform probabilistic models of prime races. These approaches prioritize exactness or conceptual clarity over scalability, highlighting the floor function's utility in theoretical number theory at the expense of practicality.[29][30]Zeta Function and Euler's Constant

The Euler-Mascheroni constant arises in analytic number theory as the limiting difference between the partial sums of the harmonic series and the natural logarithm: This constant, approximately 0.57721, encodes the asymptotic behavior of the harmonic numbers , where . The floor function enters representations of through error terms and series expansions that truncate or adjust for integer parts, providing precise control over convergence in these limits.[32] One such representation is the alternating series involving the floor of the base-2 logarithm: Discovered by Vacca in 1910 and generalized by Gerst in 1969, this series leverages the floor function to capture stepwise increases in , ensuring conditional convergence while linking discrete integer truncation to the continuous limit defining . The floor here acts as an integer truncation operator, aligning the logarithmic growth with the harmonic sum's divergence.[33] The error in the approximation can be expressed exactly using the floor function via an integral over the fractional part : This form, due to Young (1991), highlights how the floor function quantifies the oscillatory deviation from the logarithmic approximation, with the integral converging as due to the bounded nature of the fractional part (0 ≤ {x} < 1). Such expressions facilitate numerical computation and error bounds in series involving .[33] The Riemann zeta function for is defined by the Dirichlet series , and its partial sums connect directly to at the pole , where the Laurent expansion is . For efficient approximation, the partial sum up to incorporates a floor-corrected remainder via the Euler-Maclaurin formula: valid for and . This integral term uses the floor function to account for the fractional deviation in the continuous extension of the tail sum, improving convergence over the basic integral approximation . The error decreases rapidly for large , as the integrand is bounded by , and specializes at to the representation of above.[34] These floor-involved corrections underscore the role of integer truncation in analytic continuations and asymptotic analyses, bridging discrete sums to continuous functions in number theory. For instance, the zeta partial sum's accuracy relies on the floor's ability to model the "sawtooth" fractional part, ensuring bounded errors that align with the scale of itself.[34]Applications in Combinatorics and Analysis

Digit Counting

The floor function plays a key role in determining the number of digits required to represent a positive integer in a given base, providing an efficient logarithmic computation. For base 10, the number of decimal digits in is given by the formulaThis expression leverages the properties of logarithms to count digits without iterative division or string conversion.[35][36] To derive this, consider that a positive integer with decimal digits satisfies . Taking the base-10 logarithm yields , which simplifies to . The floor function then extracts the greatest integer less than or equal to , so , and thus . This holds for all .[36][35] The formula generalizes to any integer base , where the number of digits in is . The proof follows analogously: requires digits in base if , leading to and . In practice, is often computed as for numerical efficiency.[37][38] Edge cases require care. For , , so , which is correct as 1 has one digit. For , the logarithm is undefined, so the formula does not apply directly; conventionally, 0 is treated as having one digit, often handled by a special case in implementations.[36][37]

Permutation-Like Structures

In combinatorics, permutation-like structures refer to arrangements or sequences where elements are chosen without repetition, akin to partial or full permutations of a set. The floor function arises in the exact counting of such structures, particularly in cases where closed-form expressions involve approximations rounded to the nearest integer. The number of k-length strings over an alphabet of size n with no repeated characters is the number of injections (or ordered selections without replacement), given by the permutation formula for integers , and 0 otherwise.[39] This counts the ways to form sequences where each position has a distinct symbol from the alphabet. The total number of non-empty strings of length at most k without repeats is then , which simplifies to but is typically computed directly from the product form for efficiency. A prominent example of floor's role in permutation-like structures is the counting of derangements, which are permutations of n elements with no element in its original position—effectively sequences without "fixed-point repeats." The number of derangements, denoted !n or the subfactorial, is exactly for n > 0, where e ≈ 2.71828 is the base of the natural logarithm.[40] This formula provides a direct computational method without summing the inclusion-exclusion series !n = n! \sum_{i=0}^n \frac{(-1)^i}{i!}, and it holds because the fractional part of n!/e alternates around 1/2 in a way that the floor adjustment yields the integer count. For instance, !5 = 44, as \left\lfloor 120 / e + 1/2 \right\rfloor = \left\lfloor 44.145 + 0.5 \right\rfloor = 44. Derangements model problems like the hat-check scenario, where n hats are randomly redistributed with none returning to their owner. The probability of a random permutation being a derangement approaches 1/e ≈ 0.3679 as n grows large.[41] These applications highlight the floor function's utility in providing integer-exact expressions for otherwise irrational approximations in combinatorial enumeration, ensuring precise counts for permutation-like avoidance constraints.Factorial Factors

The exponent of a prime in the prime factorization of , known as the -adic valuation , is determined by de Polignac's formula: [42] This infinite sum terminates in practice, as terms vanish for such that .[42] For instance, with and , indicating that divides .[43] The formula arises from a counting argument: each term represents the number of integers from 1 to divisible by , thereby contributing at least factors of in total across the product defining . Summing these terms accounts for all factors of exactly once per occurrence in the prime factorization of each summand.[42] De Polignac's formula supports refinements to Stirling's approximation of in analytic number theory, where the exact prime exponents enable precise logarithmic expansions and error bounds in asymptotic analyses, such as those establishing prime existence in short intervals.Rounding and Approximations

The floor and ceiling functions form the basis of many rounding algorithms, providing precise control over how real numbers are approximated to integers. For positive real numbers , the standard rounding to the nearest integer is achieved via the formula , which selects the closest integer and, in cases of exact halfway points (e.g., where is an integer), rounds away from zero toward the higher integer.[44] This method is widely implemented in computational systems and mathematical software for its simplicity and effectiveness in general-purpose rounding.[45] Variants of this approach address specific needs, such as banker's rounding (also known as round-half-to-even), which modifies the behavior for halfway cases to round to the nearest even integer, reducing cumulative bias in repeated calculations like financial summations or statistical averaging.[45] In banker's rounding, the floor function can be combined with conditional logic: for example, is adjusted if the result is odd at halfway points, ensuring consistency across implementations. Halfway ties are thus broken consistently using floor or ceiling operations aligned with the even-integer rule, promoting fairness in applications where rounding errors accumulate over many operations.[46] In financial contexts, the ceiling function is frequently employed for upward rounding to ensure conservative estimates, such as rounding transaction amounts up to the next cent or unit to avoid undercharging.[47] For instance, financial software uses where is the significance (e.g., 0.05 for nickel increments), guaranteeing the result is at or above the input.[48] A key property in approximation theory is the error bound provided by these functions: for any real , , as the difference is the fractional part satisfying .[5] Similarly, . These bounds are essential for analyzing truncation errors in numerical methods and proving convergence in integer-based approximations.[5]Computational Implementations

Programming Languages

In C and C++, the floor and ceiling functions are provided in the standard library header<math.h> (C) or <cmath> (C++). The floor(x) function computes the largest integer not greater than the floating-point argument x, returning the result as a double (or float for floorf variants). Similarly, ceil(x) returns the smallest integer not less than x as a double. These functions follow IEEE 754 semantics and are available across all standard-compliant implementations.[49][50]

Python's math module offers math.floor(x) and math.ceil(x), which return an integer representing the floor or ceiling of x. Since Python 3.0, these functions return an int type for finite inputs, delegating to the object's __floor__ or __ceil__ method if x is not a float. For negative numbers, both round toward negative infinity, consistent with mathematical definitions.[51][52]

In JavaScript, the global Math object provides Math.floor(x) and Math.ceil(x), which operate on the Number type (IEEE 754 double-precision floats) and return an integer value (as a Number). Math.floor(x) returns the largest integer less than or equal to x, rounding toward negative infinity for negatives (e.g., Math.floor(-3.7) yields -4). Math.ceil(x) does the opposite, rounding toward positive infinity. These have been consistent since early ECMAScript editions, with no directional change for negatives in pre-ES6 versions.[53][54]

Common edge cases across these languages follow IEEE 754 rules where applicable. For NaN inputs, floor and ceil return NaN in C/C++ and JavaScript, while Python's math.floor and math.ceil return float('nan'). Infinities are preserved: floor(+∞) and ceil(+∞) return +∞, and similarly for -∞. In Python, for infinite inputs, math.floor and math.ceil return the corresponding infinite value as a float. Zeros (including signed -0) are returned unchanged. For large finite floats near the maximum representable value (e.g., around 1.8e308 in double precision), the functions return the value itself if it is already an exact integer, avoiding overflow since such values are precisely representable.[55][56][53][57]

Performance optimizations for floor and ceiling often leverage hardware instructions on x86 architectures. Implementations may use inline assembly to set the FPU rounding mode to "down" (for floor) before an FRNDINT instruction, then restore the mode, though this can be slow due to state changes. Modern x86 processors (via SSE4.1 and later) support direct single-instruction rounding with ROUNDSD or ROUNDPD, enabling toward-negative-infinity modes without mode switches, improving throughput in loops. The FILD instruction loads integers to floating-point but is not directly for flooring floats; it's used in hybrid integer-float conversions.[58]

Algorithms and Efficiency

The computation of the floor function and ceiling function for floating-point numbers relies on efficient algorithms that leverage the binary representation defined by the IEEE 754 standard. More efficient implementations employ bit manipulation on the IEEE 754 binary floating-point format, particularly for positive . This method extracts the sign, exponent, and mantissa bits from the 64-bit (double precision) or 32-bit (single precision) representation; for positive values, the fractional part is cleared by masking the lower mantissa bits based on the exponent, effectively truncating toward zero, which coincides with flooring for non-negative inputs.[59][60] For negative , direct bit manipulation requires adjustment to account for rounding toward negative infinity; a standard technique uses the identity , computing the ceiling of the negated value and negating the result, which avoids complex carry propagation in the mantissa.[59] These bit-level operations achieve O(1) time complexity on modern hardware supporting IEEE 754, as they involve fixed-width integer manipulations independent of 's magnitude within the representable range. However, precision issues arise for very large (e.g., beyond in double precision), where the unit in the last place (ulp) exceeds 1, causing non-integer to lose fractional detail and potentially yielding as the nearest representable integer rather than the exact mathematical floor.[60] Vectorized implementations further enhance efficiency for array processing, as in NumPy's universal functions (ufuncs), which apply floor element-wise using SIMD instructions like SSE or AVX on compatible hardware, enabling parallel computation across multiple data elements in a single operation.Historical Development

The concept of the floor function, representing the greatest integer less than or equal to a real number, traces its roots to ancient mathematics through the Euclidean algorithm, which implicitly relies on the integer quotient obtained from division. This algorithm, detailed in Euclid's Elements around 300 BCE, computes the greatest common divisor of two integers by repeated division, where the quotient is effectively the floor of the ratio of the dividend to the divisor.[61] In the late 18th century, Adrien-Marie Legendre formalized the notion of the "entier" (integer part) in 1798 while working on the law of quadratic reciprocity in his Théorie des nombres, marking an early explicit reference to the function in number theory. Shortly thereafter, Carl Friedrich Gauss introduced the bracket notation for the greatest integer less than or equal to x in 1808, as part of his third proof of quadratic reciprocity in Disquisitiones Arithmeticae.[5] During the 19th century, the integer part gained prominence in mathematical analysis; for instance, Charles Hermite employed it in studies of approximation and transcendental numbers around the 1870s, including in his 1873 proof of the transcendence of e. The early 20th century saw further standardization of notation, with the square brackets persisting until mid-century. In 1962, Kenneth E. Iverson coined the terms "floor" and "ceiling" functions and introduced the modern symbols ⌊x⌋ and ⌈x⌉ in his book A Programming Language, resolving ambiguities in prior notations like , which had been repurposed for other uses such as the Iverson bracket.[5] This shift facilitated clearer expression in both pure mathematics and emerging computational contexts. In the late 20th century, the functions were integrated into computing standards, notably through the IEEE 754 floating-point arithmetic specification ratified in 1985, which defines rounding modes including those equivalent to floor and ceiling operations for precise numerical computations. The 21st century has seen renewed interest in number theory and applications, including brief but essential roles in post-2000 lattice-based cryptography schemes, such as those relying on lattice reduction algorithms like LLL (introduced in 1982 but widely adopted later) for key generation and decoding.References

- https://proofwiki.org/wiki/De_Polignac%27s_Formula

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\lfloor x\rfloor +\lfloor y\rfloor &\leq \lfloor x+y\rfloor \leq \lfloor x\rfloor +\lfloor y\rfloor +1,\\[3mu]\lceil x\rceil +\lceil y\rceil -1&\leq \lceil x+y\rceil \leq \lceil x\rceil +\lceil y\rceil .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c51c4db96365020b998169d24d9df06a4db2b74d)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&\left\lfloor {\frac {x{\vphantom {1}}}{n}}\right\rfloor +\left\lfloor {\frac {m+x}{n}}\right\rfloor +\left\lfloor {\frac {2m+x}{n}}\right\rfloor +\dots +\left\lfloor {\frac {(n-1)m+x}{n}}\right\rfloor \\[5mu]=&\left\lfloor {\frac {x{\vphantom {1}}}{m}}\right\rfloor +\left\lfloor {\frac {n+x}{m}}\right\rfloor +\left\lfloor {\frac {2n+x}{m}}\right\rfloor +\cdots +\left\lfloor {\frac {(m-1)n+x}{m}}\right\rfloor .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3dbbd8db363654b80187d2b59fbc7e82d5291350)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\left\lfloor {\frac {\left\lfloor {\frac {x}{m}}\right\rfloor }{n}}\right\rfloor &=\left\lfloor {\frac {x}{mn}}\right\rfloor \\[4px]\left\lceil {\frac {\left\lceil {\frac {x}{m}}\right\rceil }{n}}\right\rceil &=\left\lceil {\frac {x}{mn}}\right\rceil .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f44075408c5b7a7b2cfde72dfb6525efed3bc97d)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\left({\frac {q}{p}}\right)&=(-1)^{\left\lfloor {\frac {q}{p}}\right\rfloor +\left\lfloor {\frac {2q}{p}}\right\rfloor +\dots +\left\lfloor {\frac {mq}{p}}\right\rfloor },\\[5mu]\left({\frac {p}{q}}\right)&=(-1)^{\left\lfloor {\frac {p}{q}}\right\rfloor +\left\lfloor {\frac {2p}{q}}\right\rfloor +\dots +\left\lfloor {\frac {np}{q}}\right\rfloor }.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b0ef8e9e25f4bb73b3c8d935ec673b29c50bf548)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\left({\frac {2}{p}}\right)&=(-1)^{\left\lfloor {\frac {p+1}{4}}\right\rfloor },\\[5mu]\left({\frac {3}{p}}\right)&=(-1)^{\left\lfloor {\frac {p+1}{6}}\right\rfloor }.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d5895c01c9ac887cbbea1493c4023f5362fbf1b4)