Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chengde

View on WikipediaKey Information

| Chengde | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 承德 | ||||||||

| Postal | Chengte | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Upholding Virtue Receiving Virtue | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Rehe | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 熱河(兒) | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 热河(儿) | ||||||||

| Postal | Jehol | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Hot River | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Халуун гол | ||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠬᠠᠯᠠᠭᠤᠨ ᠭᠣᠣᠯ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||

| Manchu script | ᠊ᡵᡩᡝᠮᡠ ᠪᡝ ᠠᠯᡳᡥᠠ | ||||||||

| Abkai | Erdemu Be Aliha | ||||||||

Chengde, formerly known as Jehol and Rehe, is a prefecture-level city in Hebei province, situated about 225 kilometres (140 mi) northeast of Beijing. It is best known as the site of the Mountain Resort, a vast imperial garden and palace formerly used by the Qing emperors as summer residence.[3] The permanent resident population is approximately 3,473,200 in 2017.

History

[edit]

In 1703, the Kangxi Emperor made Chengde his summer residence. Constructed throughout the eighteenth century, the Mountain Resort was used by both the Yongzheng and Qianlong emperors. The site is currently an UNESCO World Heritage Site. Since the seat of government followed the emperor, Chengde was a political center of the Chinese empire during these times.

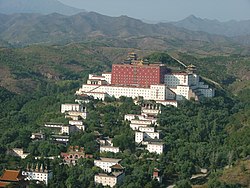

The city of Jehol—an early romanization of Rehe via the French transcription of the northern suffix ér as eul[4]—reached its height under the Qianlong Emperor 1735-1796 (died 1799). The great Putuo Zongcheng Temple, loosely based on the Potala in Lhasa, was completed after just four years of work in 1771. It was heavily decorated with gold and the emperor worshipped in the Golden Pavilion. In the temple itself was a bronze-gilt statue of Tsongkhapa, the Reformer of the Gelugpa sect.

Under the Republic of China, Chengde was the capital of Rehe province. From 1933 to 1945 the city was under Japanese control as a part of the Manchurian puppet state known as Manchukuo. After World War II the Kuomintang government regained jurisdiction. In 1948, the People's Liberation Army took control of Chengde. It would remain a part of Rehe until 1955, when the province was abolished, and the city was incorporated into Hebei.

The city is home to large populations of ethnic minorities, Mongol and Manchu in particular.

Geography

[edit]

Chengde is located in the northeastern portion of Hebei, with latitude 40° 12'-42° 37' N, and longitude 115° 54'-119° 15' E, and contains the northernmost point in the province. It borders Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Beijing, and Tianjin. Neighbouring prefecture-level provincial cities are Qinhuangdao and Tangshan on the Bohai Gulf, and land-locked Zhangjiakou. Due to its Liaoning border, it is often considered a part of both the North and Northeast China regions. From north to south the prefecture stretches 269 kilometres (167 mi), and from west to east 280 kilometres (174 mi), for a total area of 39,702.4 square kilometres (15,329.2 sq mi), thus occupying 21.2% of the total provincial area. It is by area the largest prefecture in the province, though as most of its terrain is mountainous, its population density is low.

The Jehol or Rehe ("Hot River"), which gave Chengde its former name, was so named because it did not freeze in winter. Most sections of the river's former course are now dry because of modern dams.

Climate

[edit]Chengde has a four-season, monsoon-influenced humid continental climate (Köppen Dwa), with widely varying conditions through the prefecture due to its size: winters are moderately long, cold and windy, but dry, and summers are hot and humid. Near the city, however, temperatures are much cooler than they are in Beijing, due to the higher elevation: the monthly 24-hour average temperature ranges from −9.3 °C (15.3 °F) in January to 24.2 °C (75.6 °F) in July, and the annual mean is 8.93 °C (48.1 °F). Spring warming is rapid, but dust storms can blow in from the Mongolian steppe; autumn cooling is similarly quick. Precipitation averages at about 504 millimetres (19.8 in) for the year, with more than two-thirds of it falling during the three summer months. With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 50% in July to 69% in October, the city receives 2,746 hours of sunshine annually.

| Climate data for Chengde, elevation 422 m (1,385 ft), (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

28.4 (83.1) |

34.3 (93.7) |

39.3 (102.7) |

41.3 (106.3) |

43.3 (109.9) |

38.9 (102.0) |

35.4 (95.7) |

32.8 (91.0) |

22.3 (72.1) |

12.3 (54.1) |

43.3 (109.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −1.4 (29.5) |

3.4 (38.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

19.6 (67.3) |

26.0 (78.8) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.5 (85.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

16.4 (61.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −8.8 (16.2) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

3.3 (37.9) |

11.8 (53.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

24.3 (75.7) |

22.9 (73.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

9.3 (48.7) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −14.4 (6.1) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

4.3 (39.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.9 (60.6) |

19.3 (66.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

3.1 (37.6) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

3.0 (37.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.2 (−17.0) |

−23.7 (−10.7) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

−8.7 (16.3) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−18.8 (−1.8) |

−24.7 (−12.5) |

−27.2 (−17.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1.5 (0.06) |

3.9 (0.15) |

7.9 (0.31) |

22.7 (0.89) |

49.5 (1.95) |

95.7 (3.77) |

141.1 (5.56) |

101.5 (4.00) |

49.4 (1.94) |

30.9 (1.22) |

10.4 (0.41) |

2.0 (0.08) |

516.5 (20.34) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.4 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 4.8 | 7.5 | 12.0 | 13.3 | 10.7 | 7.7 | 5.1 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 72.2 |

| Average snowy days | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 14.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 52 | 46 | 41 | 40 | 47 | 62 | 73 | 74 | 70 | 61 | 58 | 55 | 57 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 196.2 | 198.6 | 234.9 | 243.2 | 265.2 | 221.3 | 197.0 | 212.3 | 217.2 | 215.2 | 182.1 | 182.0 | 2,565.2 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 66 | 66 | 63 | 61 | 59 | 49 | 43 | 50 | 59 | 63 | 62 | 64 | 59 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[5][6][7] all-time extreme temperature[8][9] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Chengde comprises:

| Map | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Hanzi | Hanyu Pinyin | Population (2004 est.) |

Area (km2) | Density (/km2) | |

| Shuangqiao District | 双桥区 | Shuāngqiáo Qū | 290,000 | 311 | 932 | |

| Shuangluan District | 双滦区 | Shuāngluán Qū | 100,000 | 250 | 400 | |

| Yingshouyingzi Mining District | 鹰手营子 矿区 |

Yīngshǒuyíngzi Kuàngqū |

70,000 | 148 | 473 | |

| Pingquan City | 平泉市 | Píngquán Shì | 470,000 | 3,297 | 143 | |

| Chengde County | 承德县 | Chéngdé Xiàn | 470,000 | 3,990 | 118 | |

| Xinglong County | 兴隆县 | Xīnglóng Xiàn | 320,000 | 3,116 | 103 | |

| Luanping County | 滦平县 | Luánpíng Xiàn | 320,000 | 3,195 | 100 | |

| Longhua County | 隆化县 | Lónghuà Xiàn | 420,000 | 5,474 | 77 | |

| Fengning Manchu Autonomous County |

丰宁满族 自治县 |

Fēngníng Mǎnzú Zìzhìxiàn |

380,000 | 8,747 | 43 | |

| Kuancheng Manchu Autonomous County |

宽城满族 自治县 |

Kuānchéng Mǎnzú Zìzhìxiàn |

230,000 | 1,933 | 119 | |

| Weichang Manchu and Mongol Autonomous County |

围场满族 蒙古族自治县 |

Wéichǎng Mǎnzú Měnggǔzú Zìzhìxiàn |

520,000 | 9,058 | 57 | |

Sport

[edit]The first ever bandy match in China was organised in Chengde in January 2015 and was played between the Russian and Swedish top clubs Baykal-Energiya and Sandviken.[10] Chengde city was one of the initiators when the China Bandy Federation was founded in December 2014.[11] The city hosted the 2018 Women's Bandy World Championship.[12][13][14] While the record number of participants in previous Women's Bandy World Championships was 7, the organisers had thought out measures with the goal to attract 12 participating countries.[15] However, in the end 8 teams participated.

Religion

[edit]Chengde is the seat of the Catholic Diocese of Chengde.

Transport

[edit]

With road and railroad links to Beijing, Chengde has developed into a distribution hub, and its economy is growing rapidly. The newly built Jingcheng Expressway connects Chengde directly to central Beijing, and more freeways are planned for the city. The city's new airport was opened on 31 May 2017.[16] It is located 19.5 kilometres (12.1 mi) northeast of the city center in Tougou Town, Chengde County.

The Beijing–Harbin high-speed railway, completed in January 2021, has 5 stations within Chengde.

Sights

[edit]

The project of building Chengde Mountain Resort started in 1703 and finished in 1790. The whole mountain resort covers an area 5,640,000 square meters. It is the largest royal garden in China. The wall of the mountain resort is over 10,000 meters in length. In summers, emperors of the Qing dynasty came to the mountain resort to relax themselves and escape from the high temperature in Beijing.

The whole Resort can be divided into three areas which are lakes area, plains area and hills area. The lakes area, which includes 8 lakes, covers an area of 496,000 square meters. The plains area covers an area of 607,000 square meters. The emperors held horse races and hunted in the area. The largest area of the three is the hills area. It covers an area of 4,435,000 square meters. Hundreds of palaces and temples were built on the hills in this area.

The elaborate Mountain Resort features large parks with lakes, pagodas, and palaces ringed by a wall. Outside the wall are the Eight Outer Temples (外八庙), built in varying architectural styles drawn from throughout China. One of the best-known of these is the Putuo Zongcheng Temple, built to resemble the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet. The resort and outlying temples were made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994. The nearby Puning Temple, built in 1755, houses the world's tallest wooden statue of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara.

Another popular attraction of the Chengde area is Sledgehammer Peak (磬锤峰), a large rock formation in the shape of an inverted sledgehammer. A variety of other mountains, valleys, and grasslands lie within the borders of the city.

Gallery

[edit]-

Double towers mountain in Chengde city.

-

Jinshanling is a section of the Great Wall of China located in the mountainous area in Luanping County, Chengde.

-

Mùlán imperial hunting ground in Weichang County, northern Chengde.

-

Mùlán imperial hunting ground.

Sister cities

[edit]Chengde has city partnerships with the following locations:

Santo André, São Paulo, Brazil

Santo André, São Paulo, Brazil Takasaki, Gunma, Japan

Takasaki, Gunma, Japan Dakota County, Minnesota, United States

Dakota County, Minnesota, United States Kashiwa, Chiba, Japan[17]

Kashiwa, Chiba, Japan[17]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, ed. (2019). China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook 2017. Beijing: China Statistics Press. p. 46. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ 河北省统计局、国家统计局河北调查总队 (2016). 《河北经济年鉴-2018》. China Statistics Press. ISBN 978-7-5356-7824-9. Archived from the original on 2020-03-26. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- ^ Hedin (1933), pp. 1, 14.

- ^ Forêt (2000), p. xiv.

- ^ 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Experience Template" 中国气象数据网 (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ 中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年). China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ "Extreme Temperatures Around the World". Retrieved 2024-09-22.

- ^ "Chengde Climate: 1991–2020". Starlings Roost Weather. Retrieved 8 July 2025.

- ^ "Picture of the teams from the homepage of Baykal-Energiya". Archived from the original on 2016-06-11. Retrieved 2016-05-03.

- ^ "China Bandy Federation: China National Bandy Team". chinabandy.org. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Women's World Bandy Championship awarded to China". www.insidethegames.biz. February 3, 2017.

- ^ "Rapport från internationella förbundets kongress". Svenska Bandyförbundet (in Swedish).

- ^ 哈尔滨体育学院女子班迪球队赴美参加世界A组锦标赛 - 竞训新闻 - 哈尔滨体育学院 (in Chinese (China)). Harbin Sport University. Archived from the original on 2017-09-06. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- ^ Женский ЧМ — в парке Императорской резиденции - Архив новостей - Федерация хоккея с мячом России. rusbandy.ru (in Russian).

- ^ 河北承德普宁机场正式通航 (in Chinese). Xinhua. 1 June 2017. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "International Exchange". List of Affiliation Partners within Prefectures. Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR). Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]- Forêt, Philippe (2000), Mapping Chengde: The Qing Landscape Enterprise, Honalulu: University of Hawai`i Press, ISBN 9780824822934.

- Hedin, Sven (1933), "Jehol: City of Emperors", Nature, 131 (3302): 184, Bibcode:1933Natur.131..184., doi:10.1038/131184a0, S2CID 27326056.

External links

[edit]Chengde

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and early settlement

Archaeological investigations have uncovered evidence of Neolithic settlements in northern Hebei, including sites near Chengde dating to the late Neolithic period, indicative of early human activity in the region characterized by primitive agricultural and hunting-gathering economies.[5] These findings align with broader patterns of sedentary communities emerging in adjacent basins like the Xilamulun-Liao River area around 8000–6000 BCE, where millet cultivation and pottery production marked the transition to farming lifestyles.[6] During the Khitan-led Liao dynasty (907–1125), the Chengde area formed part of the northern frontier territories under Khitan control, with sparse village settlements reflecting its role as a transitional zone between steppe nomadism and agrarian societies.[7] The subsequent Jurchen Jin dynasty (1115–1234 maintained administrative oversight of the region, designating it within Zhongshan prefecture and continuing the pattern of limited population density amid military outposts and local clans.[7] Under the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), Chengde remained a sparsely inhabited frontier, serving as a buffer between the imperial core and northern nomadic groups, with governance focused on tribute extraction and defense rather than intensive settlement.[7] This era reinforced the area's peripheral status, with economic activities centered on pastoralism and intermittent trade routes.[7]Qing imperial era

The Kangxi Emperor initiated construction of the imperial summer residence in Chengde in 1703 during a northern inspection tour, selecting the site for its cooler climate relative to Beijing and proximity to the Mulan hunting grounds established in 1681, which facilitated annual imperial hunts essential to preserving Manchu martial traditions and fostering alliances with Mongol nobility.[4] This retreat, known as Bishu Shanzhuang or the Mountain Resort, served as a strategic base for administering border regions and conducting military exercises, with main structures completed by 1711.[8] The development reflected Qing priorities in environmental adaptation and geopolitical consolidation, transforming a modest villa into a sprawling complex that miniaturized the empire's diverse landscapes.[4] Under the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796), construction peaked with extensive expansions from 1737 onward, including the addition of twelve outlying temples between 1703 and 1792 that incorporated Han, Mongolian, and Tibetan architectural styles to symbolize the dynasty's cosmopolitan dominion over Inner Asia.[4] These Eight Outer Temples, among others, were built post-1750s to commemorate military victories and reinforce cultural integration, such as after the pacification of the Dzungar Khanate.[8] Qianlong spent 52 summers there, using the resort to project imperial authority and legitimize Manchu rule through landscape engineering that evoked loyalty from peripheral ethnic groups.[4] Chengde functioned as a diplomatic center, where emperors hosted tribute missions and leaders from Mongolia and Tibet to solidify alliances via shared Buddhist rituals, hunts, and banquets, thereby extending Qing influence without permanent garrisons.[8] Notable events included the 1755 reception of four Mongol clans, the 1771 arrival of Torghut Mongol Khan Ubashi with 170,000 followers, and the 1780 visit by the Sixth Panchen Lama for Qianlong's 70th birthday, each accompanied by monumental inscriptions and temple dedications to perpetuate hierarchical bonds.[8] This approach causally linked seasonal relocation to political stability, as the resort's isolation from Beijing enabled discreet negotiations that bound vassals through displays of imperial reciprocity rather than coercion alone.[4]20th century transitions

Following the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, which ended the Qing dynasty, Chengde transitioned from an imperial summer retreat to a standard county-level administrative unit within the Republic of China's Zhili Province, with its surrounding region designated as a special administrative district to manage the former imperial lands.[9] This marked the loss of its unique provincial-like status under the empire, integrating it into the republican provincial structure without dedicated oversight for its historical sites. In 1928, the Nationalist government formalized Rehe Province, elevating Chengde to its capital and encompassing territories north of the Great Wall previously fragmented under earlier administrations.[10] Japanese forces invaded Rehe Province during Operation Nekka in February 1933, launching the Battle of Rehe on February 21 and capturing Chengde without resistance by March 4, thereby placing the province under Japanese military control.[11] This occupation integrated Rehe into the puppet Mengjiang United Autonomous Government by 1939, where Japanese authorities exploited local resources and suppressed resistance, maintaining dominance until Japan's surrender in August 1945.[12] Postwar recovery briefly restored Rehe to Republic of China administration, but civil conflict intensified as Communist forces advanced in the region. The People's Liberation Army seized Chengde in 1948 amid the Liaoshen Campaign's extension into northern Hebei, establishing Communist control ahead of the broader Pingjin Campaign that captured Beijing in January 1949.[13] With the founding of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949, Chengde remained the capital of Rehe Province under initial PRC oversight. Administrative reforms in 1955 abolished Rehe Province on July 30, redistributing its territories to Hebei, Liaoning, and Inner Mongolia; Chengde was reorganized as a prefecture-level city within Hebei, streamlining local governance under the new national framework.[14]Post-1949 developments

Following the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Chengde experienced steady population and economic growth, with significant industrial expansion commencing in the late 1950s as a center for heavy industry.[9] This period aligned with the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962), during which local efforts emphasized resource extraction, including mining operations for iron ore and coal, as well as forestry activities that contributed to regional deforestation, reducing forest cover in nearby areas like Saihanba to approximately 10% by the early 1960s.[9] [15] These initiatives aimed to rapidly industrialize but resulted in environmental degradation, setting the stage for later restoration projects. Economic reforms initiated by Deng Xiaoping in 1978 shifted national priorities toward market-oriented development, prompting Chengde to leverage its historical sites for tourism. The Mountain Resort and its Outlying Temples received UNESCO World Heritage designation in 1994, enhancing preservation efforts and attracting increased visitors, which bolstered the local economy as tourism became a key sector.[4] [9] By the 1990s, rapid tourism infrastructure growth had intensified, though it occasionally strained site management.[16] In the 2010s, Chengde pursued sustainable urbanization through eco-city initiatives, including the 2010 Declaration for Ecopolis Construction emphasizing circular economy and ecological industries.[17] As part of the second batch of National Sustainable Development Agenda Innovation Demonstration Zones, the city integrated technological innovation to promote green development, focusing on coordinated economic growth with environmental protection amid ongoing urbanization.[18] [19] These efforts aimed to balance industrial legacies with ecological restoration, such as afforestation in Saihanba, achieving over 80% forest coverage by the 2010s.[15]Geography

Location and physical features

Chengde, a prefecture-level city in northern Hebei Province, China, is situated at approximately 40°58′N 117°57′E.[20] It lies about 230 kilometers northeast of Beijing, positioned in the transitional zone between the North China Plain and the Mongolian Plateau.[21] This location places it in a strategic area historically valued for its relative seclusion and natural defenses. The prefecture encompasses an area of roughly 39,500 square kilometers, featuring diverse topography that includes rugged mountains, fertile plains, and river valleys.[22] The urban core of Chengde sits at an elevation of around 300 meters above sea level, nestled within a basin surrounded by higher elevations.[23] Chengde occupies the foothills of the Yanshan Mountains, where steep slopes and peaks dominate much of the northern and western landscapes, transitioning southward into broader alluvial plains along the Rehe River valley.[24] The Rehe River, originating from local springs, flows through the central area, carving a habitable corridor amid the otherwise mountainous terrain that facilitated agricultural development in the valleys while providing elevated retreats from lowland heat.[25] This varied physiography, with its mix of highlands and lowlands, influenced early settlement patterns by offering both defensive highlands and productive riverine zones.