Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

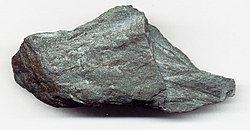

Iron ore

View on Wikipedia

Iron ores[1] are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the form of magnetite (Fe

3O

4, 72.4% Fe), hematite (Fe

2O

3, 69.9% Fe), goethite (FeO(OH), 62.9% Fe), limonite (FeO(OH)·n(H2O), 55% Fe), or siderite (FeCO3, 48.2% Fe).

Ores containing very high quantities of hematite or magnetite (typically greater than about 60% iron) are known as natural ore or [direct shipping ore], and can be fed directly into iron-making blast furnaces. Iron ore is the raw material used to make pig iron, which is one of the primary raw materials to make steel — 98% of the mined iron ore is used to make steel.[2] In 2011 the Financial Times quoted Christopher LaFemina, mining analyst at Barclays Capital, saying that iron ore is "more integral to the global economy than any other commodity, except perhaps oil".[3]

Sources

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

Elemental iron is virtually absent on the Earth's surface except as iron-nickel alloys from meteorites and sporadic forms of deep mantle xenoliths. Although iron is the fourth most abundant element in Earth's crust, composing about 5% by weight,[4] the vast majority is bound in silicate or, more rarely, carbonate minerals, and smelting pure iron from these minerals would require a prohibitive amount of energy. Therefore, all sources of iron used by human industry exploit comparatively rarer iron oxide minerals, primarily hematite.

Prehistoric societies used laterite as a source of iron ore[5]. Before the industrial revolution, most iron was obtained from widely available goethite or bog ore, for example, during the American Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Historically, much of the iron ore utilized by industrialized societies has been mined from predominantly hematite deposits with grades of around 70% Fe. These deposits are commonly referred to as "direct shipping ores" or "natural ores". Increasing iron ore demand, coupled with the depletion of high-grade hematite ores in the United States, led after World War II to the development of lower-grade iron ore sources, principally the use of magnetite and taconite.

Iron ore mining methods vary by the type of ore being mined. There are four main types of iron ore deposits worked currently, depending on the mineralogy and geology of the ore deposits. These are magnetite, titanomagnetite, hematite, and pisolitic ironstone deposits.[2]

The origin of iron can be ultimately traced to its formation through nuclear fusion in stars. Most of the iron is thought to have originated in dying stars that are large enough to explode as supernovae.[6] The Earth's core is thought to consist mainly of iron, but this is inaccessible from the surface. Some iron meteorites are thought to have originated from asteroids 1,000 km (620 mi) in diameter or larger.[7]

Banded iron formations

[edit]

Banded iron formations (BIFs) are sedimentary rocks containing more than 15% iron composed predominantly of thinly-bedded iron minerals and silica (as quartz). Banded iron formations occur exclusively in Precambrian rocks, and are commonly weakly-to-intensely metamorphosed. Banded iron formations may contain iron in carbonates (siderite or ankerite) or silicates (minnesotaite, greenalite, or grunerite), but in those mined as iron ores, oxides (magnetite or hematite) are the principal iron mineral.[8] Banded iron formations are known as taconite within North America.

The mining involves moving tremendous amounts of ore and waste. The waste comes in two forms: non-ore bedrock in the mine (overburden or interburden locally known as mullock), and unwanted minerals, which are an intrinsic part of the ore rock itself (gangue). The mullock is mined and piled in waste dumps, and the gangue is separated during the beneficiation process and is removed as tailings. Taconite tailings are mostly the mineral quartz, which is chemically inert. This material is stored in large, regulated water settling ponds.

Magnetite ores

[edit]The key parameters for magnetite ore being economic are the crystallinity of the magnetite, the grade of the iron within the banded iron formation host rock, and the contaminant elements which exist within the magnetite concentrate. The size and strip ratio of most magnetite resources are irrelevant, as a banded iron formation can be hundreds of meters thick, extend hundreds of kilometers along strike, and can easily come to more than three billion or more tonnes of contained ore.

The typical grade of iron at which a magnetite-bearing banded iron formation becomes economic is roughly 25% iron, which can generally yield a 33% to 40% recovery of magnetite by weight, to produce a concentrate grading over 64% iron by weight. The typical magnetite iron ore concentrate has less than 0.1% phosphorus, 3–7% silica, and less than 3% aluminium.

As of 2019, magnetite iron ore is mined in Minnesota and Michigan in the United States, eastern Canada, and northern Sweden.[9] Magnetite-bearing banded iron formation is mined extensively in Brazil as of 2019, which exports significant quantities to Asia, and there is a nascent and large magnetite iron ore industry in Australia.

Direct-shipping (hematite) ores

[edit]Direct-shipping iron ore (DSO) deposits (typically composed of hematite) are currently exploited on all continents except Antarctica, with the largest intensity in South America, Australia, and Asia. Most large hematite iron ore deposits are sourced from altered banded iron formations and (rarely) igneous accumulations.

DSO deposits are typically rarer than the magnetite-bearing BIF or other rocks which form their primary source, or protolith rock, but are considerably cheaper to mine and process as they require less beneficiation due to the higher iron content. However, DSO ores can contain significantly higher concentrations of penalty elements, typically being higher in phosphorus, water content (especially pisolite sedimentary accumulations), and aluminium (clays within pisolites). Export-grade DSO ores are generally in the 62–64% Fe range.[10]

Magmatic magnetite ore deposits

[edit]Granite and ultrapotassic igneous rocks were sometimes used to segregate magnetite crystals and form masses of magnetite suitable for economic concentration.[11] A few iron ore deposits, notably in Chile, are formed from volcanic flows containing significant accumulations of magnetite phenocrysts.[12]

Mine tailings

[edit]For every one ton of iron ore concentrate produced, approximately 2.5–3.0 tons of iron ore tailings will be discharged. Statistics show that there are 130 million tons of iron ore tailings discharged every year. If, for example, the mine tailings contain an average of approximately 11% iron, there would be approximately 1.41 million tons of iron wasted annually.[13] These tailings are also high in other useful metals such as copper, nickel, and cobalt,[14] and they can be used for road-building materials like pavement and filler and building materials such as cement, low-grade glass, and wall materials.[13][15][16] While tailings are a relatively low-grade ore, they are also inexpensive to collect, as they do not have to be mined. Because of this, companies such as Magnetation have started reclamation projects where they use iron ore tailings as a source of metallic iron.[13]

The two main methods of recycling iron from iron ore tailings are magnetizing roasting and direct reduction. Magnetizing roasting uses temperatures between 700 and 900 °C (1,290 and 1,650 °F) for a time of under 1 hour to produce an iron concentrate (Fe3O4) to be used for iron smelting. For magnetizing roasting, it is important to have a reducing atmosphere to prevent oxidization and the formation of Fe2O3 because it is harder to separate as it is less magnetic.[13][17] Direct reduction uses hotter temperatures of over 1,000 °C (1,830 °F) and longer times of 2–5 hours. Direct reduction is used to produce sponge iron (Fe) to be used for steel-making. Direct reduction requires more energy, as the temperatures are higher and the time is longer, and it requires more reducing agent than magnetizing roasting.[13][18][19]

Extraction

[edit]Lower-grade sources of iron ore generally require beneficiation, using techniques like crushing, milling, gravity or heavy media separation, screening, and silica froth flotation to improve the concentration of the ore and remove impurities. The results, high-quality fine ore powders, are known as fines.

Magnetite

[edit]Magnetite is magnetic, and hence easily separated from the gangue minerals and capable of producing a high-grade concentrate with very low levels of impurities.

The grain size of the magnetite and its degree of commingling with the silica groundmass determine the grind size to which the rock must be comminuted to enable efficient magnetic separation to provide a high-purity magnetite concentrate. This determines the energy inputs required to run a milling operation.

Mining of banded iron formations involves coarse crushing and screening, followed by rough crushing and fine grinding to comminute the ore to the point where the crystallized magnetite and quartz are fine enough that the quartz is left behind when the resultant powder is passed under a magnetic separator.

Generally, most magnetite banded iron formation deposits must be ground to between 32 and 45 μm (0.0013 and 0.0018 in) to produce a low-silica magnetite concentrate. Magnetite concentrate grades are generally more than 70% iron by weight and usually are low in phosphorus, aluminium, titanium, and silica, and demand a premium price.

Hematite

[edit]Due to the high density of hematite relative to associated silicate gangue, hematite beneficiation usually involves a combination of beneficiation techniques. One method relies on passing the finely-crushed ore over a slurry containing magnetite or other agent such as ferrosilicon, which increases its density. When the density of the slurry is calibrated correctly, the hematite will sink and the silicate mineral fragments will float and can be removed.[20]

Production and consumption

[edit]

| Country | Production |

|---|---|

| Australia | 817,000,000 t (804,000,000 long tons; 901,000,000 short tons) |

| Brazil | 397,000,000 t (391,000,000 long tons; 438,000,000 short tons) |

| China | 375,000,000 t (369,000,000 long tons; 413,000,000 short tons)[a] |

| India | 156,000,000 t (154,000,000 long tons; 172,000,000 short tons) |

| Russia | 101,000,000 t (99,000,000 long tons; 111,000,000 short tons) |

| South Africa | 73,000,000 t (72,000,000 long tons; 80,000,000 short tons) |

| Ukraine | 67,000,000 t (66,000,000 long tons; 74,000,000 short tons) |

| United States | 46,000,000 t (45,000,000 long tons; 51,000,000 short tons) |

| Canada | 46,000,000 t (45,000,000 long tons; 51,000,000 short tons) |

| Iran | 27,000,000 t (27,000,000 long tons; 30,000,000 short tons) |

| Sweden | 25,000,000 t (25,000,000 long tons; 28,000,000 short tons) |

| Kazakhstan | 21,000,000 t (21,000,000 long tons; 23,000,000 short tons) |

| Other countries | 132,000,000 t (130,000,000 long tons; 146,000,000 short tons) |

| Total world | 2,280,000,000 t (2.24×109 long tons; 2.51×109 short tons) |

Iron ore represents 93% of metals mined worldwide in 2021.[24] Steel, of which iron is the key ingredient, represents almost 95% of all metal used per year.[3] It is used primarily in structures, ships, automobiles, and machinery.[clarification needed]

Iron-rich rocks are common worldwide, but ore-grade commercial mining operations are dominated by the countries listed in the table aside. The major constraint to economics for iron ore deposits is not necessarily the grade or size of the deposits, because it is not particularly hard to geologically prove enough tonnage of the rocks exists. The primary constraint is the position of the iron ore relative to the market, the cost of rail infrastructure to get it to market, and the energy cost required to do so.

Mining iron ore is a high-volume, low-margin business, as the value of iron is significantly lower than that of base metals.[25] It is highly capital-intensive and requires significant investment in infrastructure, such as rail, to transport the ore from the mine to a freight ship.[25] For these reasons, iron ore production is concentrated in the hands of a few major players.

World production averages 2,000,000,000 t (2.0×109 long tons; 2.2×109 short tons) of raw ore annually. The world's largest producer of iron ore is the Brazilian mining corporation Vale, followed by Australian companies Rio Tinto and BHP. A further Australian supplier, Fortescue, has helped bring Australia's production to first in the world.

The seaborne trade in iron ore—that is, iron ore to be shipped to other countries—was 849,000,000 t (836,000,000 long tons; 936,000,000 short tons) in 2004.[25] Australia and Brazil dominate the seaborne trade, with 72% of the market.[25] BHP, Rio and Vale control 66% of this market between them.[25]

In Australia, iron ore is won from three primary sources: pisolite "channel iron deposit" ore derived by mechanical erosion of primary banded-iron formations and accumulated in alluvial channels such as at Pannawonica; and the dominant metasomatically altered banded iron formation-related ores such as at Newman, the Chichester Range, the Hamersley Range and Koolyanobbing, Western Australia. Other types of ore are coming to the fore recently,[when?] such as oxidised ferruginous hardcaps, for instance laterite iron ore deposits near Lake Argyle in Western Australia.

The total recoverable reserves of iron ore in India are about 9,602,000,000 t (9.450×109 long tons; 1.0584×1010 short tons) of hematite and 3,408,000,000 t (3.354×109 long tons; 3.757×109 short tons) of magnetite.[26] Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Jharkhand, Odisha, Goa, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu are the principal Indian producers of iron ore. World consumption of iron ore grows 10% per year [citation needed] on average, with the main consumers being China, Japan, Korea, the United States, and the European Union.

China is currently the largest consumer of iron ore, which translates to being the world's largest steel-producing country. It is also the largest importer, buying 52% of the seaborne trade in iron ore in 2004.[25] China is followed by Japan and Korea, which consume a significant amount of raw iron ore and metallurgical coal. In 2006, China produced 588,000,000 t (579,000,000 long tons; 648,000,000 short tons) of iron ore, with an annual growth of 38%.

Iron ore market

[edit]

25 October 2010 - 4 August 2022

Over the last 40 years, iron ore prices have been decided in closed-door negotiations between the small handful of miners and steelmakers, which dominate both spot and contract markets. Until 2006, prices were determined in annual benchmark negotiations between the leading iron ore producers (BHP, Rio Tinto, and Vale) and Japanese importers.[29]: 31 In 2006, Chinese company Baosteel began handling negotiations for the importer side.[29]: 31 The Chinese government replaced Baosteel with China Iron and Steel Association as lead negotiator in 2009.[29]: 109 Traditionally, the first deal reached between the major producers and the major importers sets a benchmark to be followed by the rest of the industry.[3]

Singapore Mercantile Exchange (SMX) has launched the world's first global iron ore futures contract, based on the Metal Bulletin Iron Ore Index (MBIOI) which uses daily price data from a broad spectrum of industry participants and independent Chinese steel consultancy and data provider Shanghai Steelhome's widespread contact base of steel producers and iron ore traders across China.[30] The futures contract has seen monthly volumes over 1,500,000 t (1,500,000 long tons; 1,700,000 short tons) after eight months of trading.[31]

This move follows a switch to index-based quarterly pricing by the world's three largest iron ore miners—Vale, Rio Tinto, and BHP—in early 2010, breaking a 40-year tradition of benchmark annual pricing.[32]

Fe benchmark

[edit]The global iron ore market has historically used a benchmark based on ore with an iron (Fe) content of 62 percent to set pricing standards. However, in recent decades, the average iron content of mined ore has gradually declined, while the presence of impurities has increased. Consequently, the 62 percent Fe benchmark no longer accurately represents the typical ore traded in the market, which is more commonly closer to 61 percent Fe. In response to these changes, the iron ore industry is scheduled to transition to a new pricing benchmark based on 61 percent Fe ore starting in 2026.[33]

Abundance by country

[edit]Available world iron ore resources

[edit]Iron is the most abundant element on Earth, but not in the crust.[34] The extent of the accessible iron ore reserves is not known, though Lester Brown of the Worldwatch Institute suggested in 2006 that iron ore could run out within 64 years (that is, by 2070), based on 2% growth in demand per year.[35]

Australia

[edit]Geoscience Australia calculates that the country's "economic demonstrated resources" of iron currently amount to 24 gigatonnes, or 24,000,000,000 t (2.4×1010 long tons; 2.6×1010 short tons).[citation needed] Another estimate places Australia's reserves of iron ore at 52,000,000,000 t (5.1×1010 long tons; 5.7×1010 short tons), or 30% of the world's estimated 170,000,000,000 t (1.7×1011 long tons; 1.9×1011 short tons), of which Western Australia accounts for 28,000,000,000 t (2.8×1010 long tons; 3.1×1010 short tons).[36] The current production rate from the Pilbara region of Western Australia is approximately 844,000,000 t (831,000,000 long tons; 930,000,000 short tons) per year and rising.[37] Gavin Mudd (RMIT University) and Jonathon Law (CSIRO) expect it to be gone within 30–50 years and 56 years, respectively.[38] These 2010 estimates require ongoing review to take into account shifting demand for lower-grade iron ore and improving mining and recovery techniques (allowing deeper mining below the groundwater table).

Brazil

[edit]Brazil is the second-largest producer of iron ore after Australia, accounting for 16% of the world's iron ore production. After a somewhat sluggish production volume 2010-2020, partly due to the Mariana dam disaster in 2015 and the Brumadinho dam disaster in 2019, which halted the production at the two involved mines, production has increased steadily since 2021, when Brazil produced 431,000,000 t (424,000,000 long tons; 475,000,000 short tons). In 2022 it increased to 435,000,000 t (428,000,000 long tons; 480,000,000 short tons) and in 2023 to 440,000,000 t (430,000,000 long tons; 490,000,000 short tons).[39]

The Brazilian production is expected to rise by a CAGR of 2% between 2023 and 2027,[40] and industry analyst Fitch Solutions forecasted in 2021 that Brazil's annual production will reach 592,000,000 t (583,000,000 long tons; 653,000,000 short tons) by 2030.[41]

Canada

[edit]In 2017, Canadian iron ore mines produced 49,000,000 t (48,000,000 long tons; 54,000,000 short tons) of iron ore in concentrate pellets and 13.6 million tons of crude steel. Of the 13,600,000 t (13,400,000 long tons; 15,000,000 short tons) of steel 7,000,000 t (6,900,000 long tons; 7,700,000 short tons) was exported, and 43,100,000 t (42,400,000 long tons; 47,500,000 short tons) of iron ore was exported at a value of $4.6 billion. Of the iron ore exported, 38.5% of the volume was iron ore pellets with a value of $2.3 billion, and 61.5% was iron ore concentrates with a value of $2.3 billion.[42] 46% of Canada's iron ore comes from the Iron Ore Company of Canada mine, in Labrador City, Newfoundland, with secondary sources including the Mary River Mine in Nunavut.[42][43]

India

[edit]According to the U.S. Geological Survey's 2021 Report on iron ore,[44] India is estimated to produce 59,000,000 t (58,000,000 long tons; 65,000,000 short tons) of iron ore in 2020, placing it as the seventh-largest global center of iron ore production, behind Australia, Brazil, China, Russia, South Africa, and Ukraine.

India's iron ore production in 2023 was 285,000,000 metric tonnes and was the fourth largest producer in the world.[45]

Ukraine

[edit]According to the U.S. Geological Survey's 2021 report on iron ore,[44] Ukraine is estimated to have produced 62,000,000 t (61,000,000 long tons; 68,000,000 short tons) of iron ore in 2020, placing it as the seventh largest global center of iron ore production, behind Australia, Brazil, China, India, Russia, and South Africa. Producers of iron ore in Ukraine include Ferrexpo, Metinvest, and ArcelorMittal Kryvyi Rih.

United States

[edit]In 2014, mines in the United States produced 57,500,000 t (56,600,000 long tons; 63,400,000 short tons) of iron ore with an estimated value of $5.1 billion.[46] Iron mining in the United States is estimated to have accounted for 2% of the world's iron ore output. In the United States there are twelve iron ore mines, with nine being open pit mines and three being reclamation operations. There were also ten pelletizing plants, nine concentration plants, two direct-reduced iron (DRI) plants, and one iron nugget plant that were operating in 2014.[46] In the United States, the majority of iron ore mining is in the iron ranges around Lake Superior. These iron ranges occur in Minnesota and Michigan, which combined accounted for 93% of the usable iron ore produced in the United States in 2014. Seven of the nine operational open-pit mines in the United States are located in Minnesota, as well as two of the three tailings reclamation operations. The other two active open-pit mines were located in Michigan. In 2016, one of the two mines shut down.[46] There have also been iron ore mines in Utah and Alabama; however, the last iron ore mine in Utah shut down in 2014[46] and the last iron ore mine in Alabama shut down in 1975.[47]

Smelting

[edit]Iron ores consist of oxygen and iron atoms bonded together into molecules. To convert it to metallic iron, it must be smelted or sent through a direct reduction process to remove the oxygen. Oxygen-iron bonds are strong, and to remove the iron from the oxygen, a stronger elemental bond must be presented to attach to the oxygen. Carbon is used because the strength of a carbon-oxygen bond is greater than that of the iron-oxygen bond at high temperatures. Thus, the iron ore must be powdered and mixed with coke to be burnt in the smelting process.

Carbon monoxide is the primary ingredient of chemically stripping oxygen from iron. Thus, the iron and carbon smelting must be kept in an oxygen-deficient (reducing) state to promote the burning of carbon to produce CO and not CO

2.

- Air blast and charcoal (coke): 2 C + O2 → 2 CO

- Carbon monoxide (CO) is the principal reduction agent.

- Stage One: 3 Fe2O3 + CO → 2 Fe3O4 + CO2

- Stage Two: Fe3O4 + CO → 3 FeO + CO2

- Stage Three: FeO + CO → Fe + CO2

- Limestone calcining: CaCO3 → CaO + CO2

- Lime acting as flux: CaO + SiO2 → CaSiO3

Trace elements

[edit]The inclusion of even small amounts of some elements can have profound effects on the behavioral characteristics of a batch of iron or the operation of a smelter. These effects can be both good and bad, some catastrophically harmful. Some chemicals are deliberately added, such as flux, which makes a blast furnace more efficient. Others are added because they make the iron more fluid, harder, or give it some other desirable quality. The choice of ore, fuel, and flux determines how the slag behaves and the operational characteristics of the iron produced. Ideally, iron ore contains only iron and oxygen. In reality, this is rarely the case. Typically, iron ore contains a host of elements that are often unwanted in modern steel.

Silicon

[edit]Silica (SiO

2) is almost always present in iron ore. Most of it is slagged off during the smelting process. At temperatures above 1,300 °C (2,370 °F), some will be reduced and form an alloy with the iron. The hotter the furnace, the more silicon will be present in the iron. It is not uncommon to find up to 1.5% Si in European cast iron from the 16th to 18th centuries.

The significant effect of silicon is to promote the formation of grey iron. Grey iron is less brittle and easier to finish than white iron. It is preferred for casting purposes for this reason. British metallurgist Thomas Turner reported that silicon also reduces shrinkage and the formation of blowholes, lowering the number of bad castings. However, too much silicon present in the iron leads to increased brittleness and moderate hardness.[48]

Phosphorus

[edit]Phosphorus (P) has four significant effects on iron: increased hardness and strength, lower solidus, improved fluidity, and cold shortness. Depending on the use intended for the iron, these effects are either good or bad. Bog ore often has a high phosphorus content.[49]

The strength and hardness of iron increase with the concentration of phosphorus. 0.05% phosphorus in wrought iron makes it as hard as medium-carbon steel. High-phosphorus iron can also be hardened by cold hammering. The hardening effect is true for any concentration of phosphorus. The more phosphorus, the harder the iron becomes, and the more it can be hardened by hammering. Modern steel makers can increase hardness by as much as 30%, without sacrificing shock resistance by maintaining phosphorus levels between 0.07 and 0.12%. It also increases the depth of hardening due to quenching, but at the same time, it also decreases the solubility of carbon in iron at high temperatures. This would reduce its usefulness in making blister steel (cementation), where the speed and amount of carbon absorption are the overriding considerations.

The addition of phosphorus has a downside. At concentrations higher than 0.2%, iron becomes increasingly cold short or brittle at low temperatures. Cold short is especially important for bar iron. Although bar iron is usually worked hot, its uses[example needed] often require it to be tough, bendable, and resistant to shock at room temperature. A nail that shatters when hit with a hammer or a carriage wheel that breaks when it hits a rock would not sell well.[citation needed] High enough concentrations of phosphorus render any iron unusable.[50] The effects of cold shortness are magnified by temperature. Thus, a piece of iron that is perfectly serviceable in summer might become extremely brittle in winter. There is some evidence that during the Middle Ages the very wealthy may have had a high-phosphorus sword for summer and a low-phosphorus sword for winter.[50]

Careful control of phosphorus can be of great benefit in casting operations. Phosphorus depresses the liquidus, allowing the iron to remain molten for longer and increasing fluidity. The addition of 1% can double the distance molten iron will flow.[50] The maximum effect, about 500 °C (932 °F), is achieved at a concentration of 10.2%.[51] For foundry work, Turner[52] felt the ideal iron had 0.2–0.55% phosphorus. The resulting iron-filled molds with fewer voids also shrank less. In the 19th century, some producers of decorative cast iron used iron with up to 5% phosphorus. The extreme fluidity allowed them to make very complex and delicate castings, but they could not be weight-bearing, as they had no strength.[53]

There are two remedies[according to whom?] for high-phosphorus iron. The oldest, easiest, and cheapest is avoidance. If the iron that the ore produced was cold short, one would search for a new source of iron ore. The second method involves oxidizing the phosphorus during the fining process by adding iron oxide. This technique is usually associated with puddling in the 19th century, and may not have been understood earlier. For instance, Isaac Zane, owner of Marlboro Iron Works, did not appear to know about it in 1772. Given Zane's reputation[according to whom?] for keeping abreast of the latest developments, the technique was probably unknown to the ironmasters of Virginia and Pennsylvania.

Phosphorus is generally considered to be a deleterious contaminant because it makes steel brittle, even at concentrations of as little as 0.6%. When the Gilchrist–Thomas process allowed the removal of bulk amounts of the element from cast iron in the 1870s, it was a significant development because most of the iron ores mined in continental Europe at the time were phosphorus. However, removing all the contaminants by fluxing or smelting is complicated, and so desirable iron ores must generally be low in phosphorus to begin with.

Aluminium

[edit]Small amounts of aluminium (Al) are present in many ores, including iron ore, sand, and some limestones. The former can be removed by washing the ore before smelting. Until the introduction of brick-lined furnaces, the amount of aluminium contamination was small enough that it did not affect either the iron or slag. However, when brick began to be used for hearths and the interior of blast furnaces, the amount of aluminium contamination increased dramatically. This was due to the erosion of the furnace lining by the liquid slag.

Aluminium is difficult to reduce. As a result, aluminium contamination of the iron is not a problem. However, it does increase the viscosity of the slag.[54][55] This will have several adverse effects on furnace operation. The thicker slag will slow the descent of the charge, prolonging the process. High aluminium will also make it more difficult to tap off the liquid slag. At the extreme, this could lead to a frozen furnace.

There are a number of solutions to a high-aluminium slag. The first is avoidance; do not use ore or a lime source with a high aluminium content. Increasing the ratio of lime flux will decrease the viscosity.[55]

Sulfur

[edit]Sulfur (S) is a frequent contaminant in coal. It is also present in small quantities in many ores, but can be removed by calcining. Sulfur dissolves readily in both liquid and solid iron at the temperatures present in iron smelting. The effects of even small amounts of sulfur are immediate and serious. They were one of the first worked out by iron makers. Sulfur causes iron to be red or hot short.[56]

Hot short iron is brittle when hot. This was a serious problem, as most iron used during the 17th and 18th centuries was bar or wrought iron. Wrought iron is shaped by repeated blows with a hammer while hot. A piece of hot, short iron will crack if worked with a hammer. When a piece of hot iron or steel cracks, the exposed surface immediately oxidizes. This layer of oxide prevents the mending of the crack by welding. Large cracks cause the iron or steel to break up. Smaller cracks can cause the object to fail during use. The degree of hot shortness is in direct proportion to the amount of sulfur present. Today, iron with over 0.03% sulfur is avoided.

Hot short iron can be worked, but it must be worked at low temperatures. Working at lower temperatures requires more physical effort from the smith or forgeman. The metal must be struck more often and harder to achieve the same result. A mildly sulfur-contaminated bar can be worked, but it requires a great deal more time and effort.

In cast iron, sulfur promotes the formation of white iron. As little as 0.5% can counteract the effects of slow cooling and a high silicon content.[57] White cast iron is more brittle, but also harder. It is generally avoided because it is difficult to work, except in China, where high-sulfur cast iron, some as high as 0.57%, made with coal and coke, was used to make bells and chimes.[58] According to Turner (1900, pp. 200), good foundry iron should have less than 0.15% sulfur. In the rest of the world, a high-sulfur cast iron can be used for making castings, but it will make poor wrought iron.

There are a number of remedies for sulfur contamination. The first, and the one most used in historic and prehistoric operations, is avoidance. Coal was not used in Europe (unlike China) as a fuel for smelting because it contains sulfur and therefore causes hot short iron. If an ore resulted in hot short metal, ironmasters looked for another ore. When mineral coal was first used in European blast furnaces in 1709 (or perhaps earlier), it was coked. Only with the introduction of hot blast from 1829 was raw coal used.

Ore roasting

[edit]Sulfur can be removed from ores by roasting and washing. Roasting oxidizes sulfur to form sulfur dioxide (SO2), which either escapes into the atmosphere or can be washed out. In warm climates, it is possible to leave pyritic ore out in the rain. The combined action of rain, bacteria, and heat oxidize the sulfides to sulfuric acid and sulfates, which are water-soluble and leached out.[59] However, historically (at least), iron sulfide (iron pyrite FeS

2), though a common iron mineral, has not been used as an ore for the production of iron metal. Natural weathering was also used in Sweden. The same process, at geological speed, results in the gossan limonite ores.

The importance attached to low-sulfur iron is demonstrated by the consistently higher prices paid for the iron of Sweden, Russia, and Spain from the 16th to 18th centuries. Today, sulfur is no longer a problem. The modern remedy is the addition of manganese, but the operator must know how much sulfur is in the iron because at least five times as much manganese must be added to neutralize it. Some historic irons display manganese levels, but most are well below the level needed to neutralize sulfur.[57]

Sulfide inclusion as manganese sulfide (MnS) can also be the cause of severe pitting corrosion problems in low-grade stainless steel such as AISI 304 steel.[60][61] Under oxidizing conditions and in the presence of moisture, when sulfide oxidizes, it produces thiosulfate anions as intermediate species, and because the thiosulfate anion has a higher equivalent electromobility than the chloride anion due to its double negative electrical charge, it promotes pit growth.[62] Indeed, the positive electrical charges born by Fe2+ cations released in solution by Fe oxidation on the anodic zone inside the pit must be quickly compensated/neutralized by negative charges brought by the electrokinetic migration of anions in the capillary pit. Some of the electrochemical processes occurring in a capillary pit are the same as those encountered in capillary electrophoresis. The higher the anion electrokinetic migration rate, the higher the rate of pitting corrosion. Electrokinetic transport of ions inside the pit can be the rate-limiting step in the pit growth rate.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Ramanaidou and Wells, 2014

- ^ a b "Iron Ore – Hematite, Magnetite & Taconite". Mineral Information Institute. Archived from the original on 17 April 2006. Retrieved 7 April 2006.

- ^ a b c Iron ore pricing emerges from stone age, Financial Times, October 26, 2009 Archived 2011-03-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Murad, Enver; Cashion, John (28 June 2011). Mossbauer Spectroscopy of Environmental Materials. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-4419-9040-2.

- ^ "(PDF) Smelting Iron from Laterite: Technical Possibility or Ethnographic Aberration?". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 10 December 2024. Retrieved 18 November 2025.

- ^ Frey, Perry A.; Reed, George H. (21 September 2012). "The Ubiquity of Iron". ACS Chemical Biology. 7 (9): 1477–1481. doi:10.1021/cb300323q. ISSN 1554-8929. PMID 22845493.

- ^ Goldstein, J.I.; Scott, E.R.D.; Chabot, N.L. (2009). "Iron meteorites: Crystallization, thermal history, parent bodies, and origin". Geochemistry. 69 (4): 293–325. Bibcode:2009ChEG...69..293G. doi:10.1016/j.chemer.2009.01.002.

- ^ Harry Klemic, Harold L. James, and G. Donald Eberlein, (1973) "Iron," in United States Mineral Resources, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 820, p.298-299.

- ^ Troll, Valentin R.; Weis, Franz A.; Jonsson, Erik; Andersson, Ulf B.; Majidi, Seyed Afshin; Högdahl, Karin; Harris, Chris; Millet, Marc-Alban; Chinnasamy, Sakthi Saravanan; Kooijman, Ellen; Nilsson, Katarina P. (12 April 2019). "Global Fe–O isotope correlation reveals magmatic origin of Kiruna-type apatite-iron-oxide ores". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1712. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1712T. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09244-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6461606. PMID 30979878.

- ^ Muwanguzi, Abraham J. B.; Karasev, Andrey V.; Byaruhanga, Joseph K.; Jönsson, Pär G. (3 December 2012). "Characterization of Chemical Composition and Microstructure of Natural Iron Ore from Muko Deposits". ISRN Materials Science. 2012 e174803. doi:10.5402/2012/174803. S2CID 56961299.

- ^ Jonsson, Erik; Troll, Valentin R.; Högdahl, Karin; Harris, Chris; Weis, Franz; Nilsson, Katarina P.; Skelton, Alasdair (10 April 2013). "Magmatic origin of giant 'Kiruna-type' apatite-iron-oxide ores in Central Sweden". Scientific Reports. 3 (1): 1644. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E1644J. doi:10.1038/srep01644. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 3622134. PMID 23571605.

- ^ Guijón, R.; Henríquez, F.; Naranjo, J.A. (2011). "Geological, Geographical and Legal Considerations for the Conservation of Unique Iron Oxide and Sulphur Flows at El Laco and Lastarria Volcanic Complexes, Central Andes, Northern Chile". Geoheritage. 3 (4): 99–315. Bibcode:2011Geohe...3..299G. doi:10.1007/s12371-011-0045-x. S2CID 129179725.

- ^ a b c d e Li, Chao; Sun, Henghu; Bai, Jing; Li, Longtu (15 February 2010). "Innovative methodology for comprehensive utilization of iron ore tailings: Part 1. The recovery of iron from iron ore tailings using magnetic separation after magnetizing roasting". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 174 (1–3): 71–77. Bibcode:2010JHzM..174...71L. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.09.018. PMID 19782467.

- ^ Sirkeci, A. A.; Gül, A.; Bulut, G.; Arslan, F.; Onal, G.; Yuce, A. E. (April 2006). "Recovery of Co, Ni, and Cu from the tailings of Divrigi Iron Ore Concentrator". Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Review. 27 (2): 131–141. Bibcode:2006MPEMR..27..131S. doi:10.1080/08827500600563343. ISSN 0882-7508. S2CID 93632258.

- ^ Das, S.K.; Kumar, Sanjay; Ramachandrarao, P. (December 2000). "Exploitation of iron ore tailing for the development of ceramic tiles". Waste Management. 20 (8): 725–729. Bibcode:2000WaMan..20..725D. doi:10.1016/S0956-053X(00)00034-9.

- ^ Gzogyan, T. N.; Gubin, S. L.; Gzogyan, S. R.; Mel'nikova, N. D. (1 November 2005). "Iron losses in processing tailings". Journal of Mining Science. 41 (6): 583–587. Bibcode:2005JMinS..41..583G. doi:10.1007/s10913-006-0022-y. ISSN 1573-8736. S2CID 129896853.

- ^ Uwadiale, G. G. O. O.; Whewell, R. J. (1 October 1988). "Effect of temperature on magnetizing reduction of agbaja iron ore". Metallurgical Transactions B. 19 (5): 731–735. Bibcode:1988MTB....19..731U. doi:10.1007/BF02650192. ISSN 1543-1916. S2CID 135733613.

- ^ Stephens, F. M.; Langston, Benny; Richardson, A. C. (1 June 1953). "The Reduction-Oxidation Process For the Treatment of Taconites". JOM. 5 (6): 780–785. Bibcode:1953JOM.....5f.780S. doi:10.1007/BF03397539. ISSN 1543-1851.

- ^ H.T. Shen, B. Zhou, et al. "Roasting-magnetic separation and direct reduction of a refractory oolitic-hematite ore" Min. Met. Eng., 28 (2008), pp. 30-43

- ^ Gaudin, A.M, Principles of Mineral Dressing, 1937

- ^ Graphic from The "Limits to Growth" and 'Finite' Mineral Resources, p. 5, Gavin M. Mudd

- ^ Tuck, Christopher. "Mineral Commodity Summaries 2017" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Tuck, Christopher. "Global iron ore production data; Clarification of reporting from the USGS" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Here's what the world mined in 2021 in one infographic". World Economic Forum. 24 October 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Iron ore pricing war, Financial Times, October 14, 2009

- ^ Qazi, Shabir Ahmad; Qazi, Navaid Shabir (1 January 2008). Natural Resource Conservation and Environment Management. APH Publishing. ISBN 978-81-313-0404-4. Retrieved 12 November 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Iron Ore - Monthly Price - Commodity Prices - Price Charts, Data, and News". IndexMundi. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ "Global price of Iron Ore | FRED | St. Louis Fed". Fred.stlouisfed.org. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Massot, Pascale (2024). China's Vulnerability Paradox: How the World's Largest Consumer Transformed Global Commodity Markets. New York, NY, United States of America: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-777140-2.

- ^ "SMX to list world's first index based iron ore futures". 29 September 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ "ICE Futures Singapore - Futures Exchange". Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ "mbironoreindex". Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Venditti, Bruno (15 August 2025). "Explaining the iron ore grade shift". MINING.COM. Retrieved 18 August 2025.

- ^ Morgan, J. W.; Anders, E. (1980). "Chemical composition of Earth, Venus, and Mercury". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 77 (12): 6973–77. Bibcode:1980PNAS...77.6973M. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.12.6973. PMC 350422. PMID 16592930.

- ^ Brown, Lester (2006). Plan B 2.0. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 109.

- ^ "Iron Ore". Government of Western Australia - Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ Western Australian Mineral and Petroleum Statistics Digest 2021–22 (PDF) (Report). Government of Western Australia Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety. 2022.

- ^ Pincock, Stephen (14 July 2010). "Iron Ore Country". ABC Science. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ "Mine production of iron ore in Brazil from 2010 to 2023". Statista. 19 April 2024. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "Iron ore production in Brazil and major projects". Mining Technology. 5 July 2024. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "Global Iron Ore Mining Outlook" (PDF). Fitch Solutions. 26 August 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ a b Canada, Natural Resources (23 January 2018). "Iron ore facts". www.nrcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "Mining the Future 2030: A Plan for Growth in the Newfoundland and Labrador Mining Industry | McCarthy Tétrault". 19 November 2018.

- ^ a b "USGS Report on Iron Ore, 2021" (PDF).

- ^ "List of countries by iron ore production", Wikipedia, 31 October 2023, retrieved 13 February 2024

- ^ a b c d "USGS Minerals Information: Iron Ore". minerals.usgs.gov. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Lewis S. Dean, Minerals in the economy of Alabama 2007Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Alabama Geological Survey, 2008

- ^ Turner 1900, p. 287.

- ^ Gordon 1996, p. 57.

- ^ a b c Rostoker & Bronson 1990, p. 22.

- ^ Rostoker & Bronson 1990, p. 194.

- ^ Turner 1900.

- ^ Turner 1900, pp. 202–204.

- ^ Kato & Minowa 1969, p. 37.

- ^ a b Rosenqvist 1983, p. 311.

- ^ Gordon 1996, p. 7.

- ^ a b Rostoker & Bronson 1990, p. 21.

- ^ Rostoker, Bronson & Dvorak 1984, p. 760.

- ^ Turner 1900, pp. 77.

- ^ Stewart, J.; Williams, D.E. (1992). "The initiation of pitting corrosion on austenitic stainless steel: on the role and importance of sulphide inclusions". Corrosion Science. 33 (3): 457–474. Bibcode:1992Corro..33..457S. doi:10.1016/0010-938X(92)90074-D. ISSN 0010-938X.

- ^ Williams, David E.; Kilburn, Matt R.; Cliff, John; Waterhouse, Geoffrey I.N. (2010). "Composition changes around sulphide inclusions in stainless steels, and implications for the initiation of pitting corrosion". Corrosion Science. 52 (11): 3702–3716. Bibcode:2010Corro..52.3702W. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2010.07.021. ISSN 0010-938X.

- ^ Newman, R. C.; Isaacs, H. S.; Alman, B. (1982). "Effects of sulfur compounds on the pitting behavior of type 304 stainless steel in near-neutral chloride solutions". Corrosion. 38 (5): 261–265. doi:10.5006/1.3577348. ISSN 0010-9312.

General and cited references

[edit]- Gordon, Robert B. (1996). American Iron 1607–1900. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Kato, Makoto; Minowa, Susumu (1969). "Viscosity Measurement of Molten Slag- Properties of Slag at Elevated Temperature (Part 1)". Transactions of the Iron and Steel Institute of Japan. 9. Tokyo: Nihon Tekko Kyokai: 31–38. doi:10.2355/isijinternational1966.9.31.

- Ramanaidou, E. R. and Wells, M. A. (2014). 13.13 "Sedimentary Hosted Iron Ores". In: Holland, H. D. and Turekian, K. K. Eds., Treatise on Geochemistry (Second Edition). Oxford: Elsevier. 313–355. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-095975-7.01115-3.

- Rosenqvist, Terkel (1983). Principles of Extractive Metallurgy. McGraw-Hill Book Company.

- Rostoker, William; Bronson, Bennet (1990). Pre-Industrial Iron: Its Technology and Ethnology. Archeomaterials Monograph No. 1.

- Rostoker, William; Bronson, Bennet; Dvorak, James (1984). "The Cast-Iron Bells of China". Technology and Culture. 25 (4). The Society for the History of Technology: 750–767. doi:10.2307/3104621. JSTOR 3104621. S2CID 112143315.

- Turner, Thomas (1900). The Metallurgy of Iron (2nd ed.). Charles Griffin & Company, Limited.

External links

[edit]- Historical documents

- History of the Iron Ore Trade on the Great Lakes (1910 Annual Report of the Lake Carriers' Association, made available online by the Michael Schwartz Library of Cleveland State University)

- James Stephen Jeans, Pioneers of the Cleveland Iron Trade (1875)

- Modern information

- Global price of Iron Ore data from the International Monetary Fund, made available via Federal Reserve Economic Data

- Iron Ore Statistics and Information from the U.S. Geological Survey's National Minerals Information Center

- usgs.gov: Iron ore (Mineral Commodity Summaries 2025)

- World's Largest Iron Ore Producers, 2023, analysis from James F. King

Iron ore

View on GrokipediaGeological Formation and Sources

Banded Iron Formations

Banded iron formations (BIFs) consist of Precambrian sedimentary rocks featuring repetitive layering of iron oxide-rich bands and silica-rich chert or quartz layers, deposited mainly from approximately 3.8 to 1.8 billion years ago, with peak abundance during the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) between 2.4 and 2.0 billion years ago.[5][6] The GOE marked a pivotal rise in atmospheric oxygen levels, primarily from cyanobacterial photosynthesis, which oxidized abundant dissolved ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) in oxygen-poor marine waters to insoluble ferric iron (Fe³⁺) oxides that settled as chemical precipitates onto the seafloor.[6][7] This process was episodic, influenced by fluctuating oxygen availability and upwelling of iron-laden hydrothermal fluids, resulting in the characteristic mm- to cm-scale banding preserved in the rock record.[6] These formations exhibit distinct stratigraphic and geochemical signatures, including low detrital content and δ¹⁸O values indicative of marine precipitation, with iron bands often comprising up to 30-40 wt% Fe in primary deposits.[8] They occur in extensive, laterally continuous sheets, some spanning hundreds of kilometers and reaching thicknesses of several hundred meters, as seen in the Archean to Paleoproterozoic successions of the Hamersley Province in Western Australia and the Carajás Province in northern Brazil.[9][8] Post-depositional alteration, particularly supergene weathering under oxidizing conditions, leached silica and other impurities from the protore, concentrating iron content through goethite formation and residual enrichment, though debates persist on the relative roles of supergene versus hypogene hydrothermal fluids in generating high-grade orebodies.[10][11] BIFs represent the dominant host for economic iron resources, accounting for over 90% of global reserves through their vast tonnage and amenability to enrichment processes.[12] Their preservation in cratonic basins provides key empirical evidence for early Earth oxygenation dynamics, with geochemical proxies like chromium isotopes indicating transient oxygen pulses predating the full GOE.[7] While primary BIFs typically grade 15-30% Fe, enriched variants exceed 60% Fe, underscoring their geological evolution from low-grade sediments to viable ore precursors without reliance on later magmatic inputs.[13][10]Sedimentary and Magmatic Deposits

Sedimentary iron ore deposits distinct from banded iron formations primarily form in shallow marine, lacustrine, or wetland environments through precipitation of iron oxides and hydroxides. Bog iron, a limonite-rich ore, accumulates in peat bogs and swamps via bacterial mediation, where iron is mobilized from surrounding soils by acidic groundwater and precipitates upon encountering oxygen or neutral pH zones near the surface.[14] These deposits, typically thin and nodular, were extensively exploited in Europe and North America before the 19th century, powering early bloomery furnaces; for instance, in colonial Virginia, bog iron supported the first commercial ironworks established in 1619 at Falling Creek.[15] Economically viable layers can regenerate within 20 years due to ongoing biogenic processes, though modern mining favors higher-grade sources.[16] Oolitic ironstones represent another sedimentary variant, characterized by concentric ooids composed of iron minerals such as chamosite, siderite, and goethite, deposited in agitated, oxygenated shelf seas during transgressive episodes. These ores, often interbedded with carbonates or shales, occur in Phanerozoic sequences like the Jurassic minette deposits of western Europe, including significant reserves in Lorraine, France, and Northamptonshire, England, which supplied iron for industrial expansion in the 18th and 19th centuries.[17] Formation involves supersaturation of seawater with iron from continental weathering, followed by accretion around microfossils or quartz grains in high-energy settings.[18] While less voluminous than Precambrian banded iron formations, oolitic deposits provided accessible, near-surface resources in pre-industrial eras. Magmatic iron deposits, in contrast, originate from igneous processes involving fractional crystallization and fluid exsolution in subvolcanic settings. Kiruna-type apatite-magnetite ores, hosted in andesitic intrusions or volcanic piles, form through immiscible iron oxide liquids segregating from mafic to felsic magmas derived from mantle sources, often in convergent tectonic regimes.[19] The Kiruna deposit in northern Sweden exemplifies this, comprising over 2 billion tonnes of ore at grades exceeding 60% Fe, with mining commencing in 1902 and cumulative extraction reaching approximately 1,600 million tonnes by the early 21st century from around 40 similar bodies in the Norrbotten region.[20] These deposits are enriched in phosphorus via associated apatite and may contain trace elements like rare earths, distinguishing them from sedimentary ores.[21] Collectively, non-banded sedimentary and magmatic deposits constitute a minor fraction of global iron resources, with over 95% of currently exploited ores tracing to sedimentary origins dominated by altered banded iron formations, yet they remain vital for specialized applications due to unique geochemical signatures such as elevated phosphorus in Kiruna-type ores.[22] Their formation underscores diverse geodynamic controls, from surficial diagenesis to deep-crustal magmatism, yielding ores historically pivotal before large-scale Precambrian exploitation.[23]Mineral Types and Composition

Hematite and Goethite Ores

Hematite, with the chemical formula Fe₂O₃, is the principal iron oxide mineral in many high-grade deposits, containing approximately 69.9% iron by weight in its pure form.[24] Goethite, FeO(OH), serves as a hydrated counterpart, with a theoretical iron content of about 62.9%.[25] These minerals dominate oxide ores suitable for direct shipping, where natural grades often exceed 60% Fe, minimizing beneficiation requirements prior to export.[24] Supergene weathering processes enrich these ores by leaching silica and other gangue minerals from precursor banded iron formations, concentrating hematite through oxidation and dehydration.[26] In regions like Australia's Pilbara Craton, specular hematite forms massive, high-grade direct-shipping ores averaging over 62% Fe, resulting from prolonged exposure to meteoric waters that dissolve impurities while preserving iron oxides.[27] Goethite commonly caps lateritic profiles, forming via hydration of primary iron oxides in tropical weathering environments, though its lower grade necessitates thermal dehydration to enhance viability for extraction.[28] The high purity of hematite-goethite ores reduces downstream processing needs, as their elevated iron content supports efficient blast furnace feed with minimal impurities. However, hematite's friable nature often generates fines during mining and handling, complicating logistics and requiring measures to mitigate dust and material loss.[29] Goethite's hydration similarly poses handling challenges, as its ochreous varieties are prone to slaking upon wetting, further emphasizing the role of natural enrichment in determining economic extractability.[30]Magnetite Ores

Magnetite ores are dominated by the iron oxide mineral magnetite (Fe₃O₄), which theoretically contains 72.4% iron by weight, the highest among common iron oxides. These ores typically occur in lower-grade deposits with 20-30% initial Fe content, embedded in banded iron formations or as massive accumulations in magmatic iron oxide-apatite (IOA) settings, but their mineral properties enable upgrading to concentrates over 65% Fe suitable for pellet production.[24] Notable deposits include the Kiruna IOA complex in northern Sweden, featuring extensive magnetite-apatite bodies that have supported large-scale mining since the early 20th century, with associated trace elements like vanadium recoverable from heavy-mineral concentrates.[31] In Australia, the Savage River deposit in Tasmania comprises volcanogenic magnetite lenses exceeding 100 million tonnes in resources, primarily massive magnetite-pyrite ores amenable to concentration.[32] Magnetite's ferromagnetic nature and high specific gravity (approximately 5.2 g/cm³) provide distinct beneficiation advantages over non-magnetic ores, facilitating efficient low-intensity magnetic separation to reject gangue minerals like quartz and silicates with minimal energy input and high recovery of fine particles below 10 μm. This process yields low-impurity concentrates (typically <5% silica), reducing downstream processing costs and environmental impacts from tailings, while complementary density-based methods like spirals enhance selectivity in complex ores.[33][34]Other Iron-Bearing Minerals

Siderite (FeCO₃), with a theoretical iron content of 48%, constitutes a carbonate ore historically mined in Europe before the dominance of higher-grade hematite and magnetite deposits.[35] Its principal value derives from high iron concentration coupled with minimal sulfur and phosphorus impurities, rendering it suitable for smelting after thermal decomposition of the carbonate structure.[36] Deposits often occur in sedimentary settings, forming through precipitation in ancient water bodies, though modern production remains limited due to processing costs and competition from oxide ores.[37] Limonite, an amorphous aggregate of hydrated iron oxides including goethite (FeO(OH)) and varying water content, typically assays 40-60% Fe in raw form but suffers from inconsistent composition and high impurity levels, confining its role to secondary or niche sources.[38] Economic extraction demands intensive beneficiation, such as washing and magnetic separation, to concentrate iron and remove silica or clay, yet global output lags behind primary ores owing to lower recovery rates and energy demands.[39] Taconite represents a low-grade siliceous iron formation, averaging 25-30% Fe and dominated by fine-grained magnetite within banded structures, extracted principally from Minnesota's Mesabi Range since the mid-20th century.[40] Processing involves crushing, grinding, magnetic separation to reject gangue, and agglomeration into pellets achieving over 65% Fe for blast furnace compatibility, enabling viability of deposits uneconomic as direct-shipping ores.[41] Per U.S. Geological Survey assessments, such ores sustain operations only if raw grades exceed approximately 20-25% Fe to permit cost-effective beneficiation yielding marketable concentrates, underscoring their niche in resource portfolios amid depleting high-grade reserves.[42]Mining Methods and Operations

Surface and Open-Pit Mining

Surface mining, encompassing open-pit operations, predominates in iron ore extraction due to the extensive, tabular nature of deposits like banded iron formations, which favor large-scale removal of shallow overburden. This method involves stripping away soil and waste rock to access ore bodies, typically viable for depths up to several hundred meters where the strip ratio—overburden volume per unit ore—remains economically favorable. Open-pit mining leverages economies of scale through massive equipment fleets, enabling high-volume output that underground methods cannot match without prohibitive costs from support infrastructure and ventilation.[1][43] The core techniques include exploratory drilling to map ore zones, followed by patterned blast hole drilling, explosive charging with ammonium nitrate-fuel oil mixtures, and controlled detonations to fracture rock into manageable sizes. Post-blast, front-end loaders or rope shovels with capacities exceeding 100 cubic meters scoop fragmented ore and waste, loading it into ultra-class haul trucks (up to 400-tonne payloads) for transport along haul roads to stockpile or primary crushers. Bench heights of 10-15 meters and pit slopes of 45-55 degrees optimize stability and efficiency, with benching allowing progressive deepening. In mega-pits, real-time monitoring via GPS and laser scanners guides operations to maintain wall angles and prevent slope failures.[44][43] Prominent examples include Vale's Serra Carajás complex in Brazil's Pará state, where open-pit bench mining targets high-grade hematite deposits exceeding 66% iron content. Operations there employ over 100 haul trucks and excavators in pits spanning kilometers, contributing significantly to Vale's annual output of around 300 million metric tons of iron ore as of 2023. Similar scale defines Australia's Pilbara region mines, operated by Rio Tinto and BHP, where automated systems enhance productivity. These sites demonstrate how vast reserves—Carajás alone holding billions of tonnes—justify capital-intensive setups yielding low per-tonne costs under $20 in optimal conditions.[44][4] Advantages stem from causal factors like reduced labor intensity and ventilation needs compared to underground extraction, enabling over 90% of global iron ore production—totaling 2.6 billion metric tons in 2023—to occur via surface methods, per U.S. Geological Survey estimates. For shallow deposits under 100 meters, stripping costs plummet as overburden thins, amplifying returns on mechanized fleets. However, depth limits arise around 300-500 meters, where escalating strip ratios inflate energy and haulage expenses, often shifting viability to underground alternatives despite open-pit's scalability.[4][45] Challenges include substantial dust generation from blasting and haulage, necessitating suppression via water sprays or polymer binders, alongside high water consumption for operations—up to 1-2 cubic meters per tonne in wet climates—though dry stacking and recycling circuits mitigate this. Land disturbance spans thousands of hectares, with pit voids posing post-closure risks, but verifiable mitigations like autonomous electric trucks, deployed at sites like Rio Tinto's Pilbara since 2018, cut emissions by 15-20% and enhance safety by minimizing human exposure. Regulatory compliance, including progressive rehabilitation, addresses biodiversity impacts in sensitive areas.[46][45]Underground Mining

Underground mining of iron ore is applied to deposits at depths where open-pit methods become inefficient due to excessive overburden ratios or geological instability, or in cases requiring surface land preservation, such as near urban areas. Access is gained through vertical shafts, inclined ramps, or horizontal adits, enabling extraction via techniques tailored to massive, steeply dipping orebodies like magnetite or hematite lenses.[47][48] Key methods include sublevel caving and block caving, which leverage gravity to induce controlled collapse of the orebody after undercutting or blasting from multiple sublevels spaced 15-30 meters apart. In sublevel caving, rings of blast holes are drilled and charged horizontally from drill drifts, fragmenting ore that caves into underlying extraction levels for mucking via loaders or conveyor systems; this suits competent, vertical deposits over 100 meters thick with minimal dilution. Block caving extends this by undercutting entire panels up to 50 meters high, allowing bulk flow through drawpoints, though it risks higher dilution in weaker iron formations. These approaches are selected for high-grade ores exceeding 60% Fe, where the premium value compensates for complexities absent in surface operations.[49][50][51] The Kiruna mine in Sweden exemplifies this transition, shifting from initial open-pit extraction in 1900 to full underground sublevel caving by the mid-20th century as the orebody extended to 2 kilometers depth, with an 80-meter-thick, 4-kilometer-long magnetite-apatite zone grading above 60% iron. In 2018, it yielded 26.9 million tonnes, representing LKAB's primary output from subsurface methods that minimize surface disruption despite the site's proximity to infrastructure.[52] Compared to open-pit mining, underground iron ore extraction incurs 2-3 times higher operating costs per tonne—driven by requirements for ventilation, ground support, and mechanized haulage—along with elevated safety hazards like rock bursts and poor air quality, necessitating rigorous engineering controls. Yet, it enables recovery of premium ores uneconomic via surface stripping, historically proliferating after the 1800s amid industrial demand for concentrated veins, as seen in the Soudan Mine's shaft operations from 1884 reaching 2,341 feet and Mesabi Range block caving from 1892 to 1961 before low-grade taconite shifted industry to pits. Today, such methods form a minority of global output, confined to select deep, high-value deposits where causal economics favor subsurface over expansive surface disturbance.[53][54][55][48]Tailings and Waste Management

Iron ore tailings consist of fine-grained residues primarily comprising quartz, hematite, goethite, and silicates, generated during beneficiation processes that separate valuable iron minerals from gangue. These wastes, amounting to 20-40% of processed ore mass, total approximately 1.4 billion tonnes annually worldwide, with major contributions from producers in Brazil, Australia, and China.[56][57] Tailings are typically discharged as thickened slurries with 60-70% solids by weight into engineered impoundments to facilitate settling and water recovery, minimizing the volume of liquid waste while containing the bulk solids.[56] Catastrophic failures of tailings dams, often triggered by liquefaction under seismic or static loading, have occurred but remain infrequent relative to the scale of global operations. The 2015 Samarco Fundão dam collapse in Brazil released 43 million cubic meters of slurry, resulting in 19 deaths and extensive downstream flooding due to inadequate stability assessments.[58] Similarly, the 2019 Brumadinho dam failure at a Vale-operated site unleashed 12 million cubic meters, causing 270 fatalities from rapid mudflow engulfing nearby structures, attributed to progressive pore pressure buildup in unmonitored upstream-raised embankments.[59] [60] Peer-reviewed analyses of historical data indicate overall tailings storage facility failure rates below 0.01% per dam-year for modern designs, though upstream methods exhibit higher vulnerability (up to 3.9% cumulative pre-2000), underscoring the causal role of construction technique over inherent instability.[61] [62] Contemporary management prioritizes risk mitigation through thickened and filtered tailings technologies, reducing reliance on large water-retaining dams. Dry stacking, involving dewatering to over 80% solids via pressure filtration before mechanical deposition, eliminates free-water impoundments, thereby averting liquefaction hazards and cutting water consumption by up to 90% compared to conventional slurried storage.[63] [64] This approach has demonstrated empirical stability in iron ore applications, with stacked piles achieving shear strengths exceeding 100 kPa under compaction, enabling reclamation of land footprints and countering critiques of perpetual environmental liability through verifiable seepage control and seismic resilience.[63] Industry adoption, as in select Brazilian and Australian operations, reflects causal improvements in geotechnical design over alarmist narratives, with no recorded dry-stack failures tied to structural inadequacy.[64]Beneficiation and Primary Processing

Hematite Ore Processing

High-grade hematite ores exceeding 60% iron content qualify as direct-shipping ores (DSO), necessitating only mechanical crushing to reduce run-of-mine material to sizes below 60 mm, followed by screening to separate lump (typically 6-30 mm) and fines fractions suitable for direct transport to steel mills without chemical or advanced beneficiation.[65][66][67] This approach leverages the ore's inherent low impurity levels, primarily silica and alumina under 4%, enabling efficient downstream smelting while avoiding energy-intensive upgrading.[68] Lower-grade hematite ores, often below 62% Fe with higher gangue content, undergo physical beneficiation centered on gravity separation to concentrate iron minerals while rejecting lighter silica and clay fractions. Primary steps include wet screening and scrubbing to liberate particles, followed by classification into coarse (>1 mm) and fine streams. Jigging, a density-based method using upward pulsed water currents in a jig bed, stratifies heavier hematite from lighter gangue, achieving effective separation for particles in the 0.15-10 mm range.[69][70] Spiral concentrators then handle finer fractions (<1 mm), exploiting centrifugal forces and hindered settling to recover hematite concentrates with minimal water usage.[70][71] In regions like India, where low-grade hematite fines constitute a significant portion of reserves (e.g., 62-65% Fe medium-grade ores), operations such as those at Tata Steel's Noamundi mine employ Batac jigs for processing classifier fines (-10+0.15 mm) at capacities up to 250 tph, complemented by spirals for deslimed slimes.[72][69] These concentrates, upgraded to 65%+ Fe, are agglomerated into sinter or pellets to mitigate handling losses from ultra-fines generated during mining and crushing.[68][71] Empirical data from such gravity circuits report iron recovery yields exceeding 85%, with optimized jig-spiral combinations minimizing waste tailings to under 20% of feed mass by maximizing hematite liberation and density differential exploitation.[73][74] This high efficiency stems from the non-magnetic nature of hematite, allowing cost-effective physical upgrading without roasting or magnetic aids, though yields vary with ore friability and particle size distribution.[75]Magnetite Ore Processing

Magnetite ore, characterized by its strong ferromagnetic properties, undergoes beneficiation primarily through magnetic separation, which exploits the inherent separability of iron oxide particles from non-magnetic gangue based on differential magnetic susceptibility. This approach enables efficient upgrading of low-grade deposits, such as those in banded iron formations, by selectively recovering magnetite grains without relying on density differences.[76][24] The process typically begins with crushing and screening to prepare the ore, followed by low-intensity magnetic separation (LIMS) using wet drum separators operating at magnetic field strengths of 0.03–0.15 Tesla. LIMS effectively captures coarse magnetite particles, producing a primary concentrate that is then subjected to grinding—often in multiple stages with ball or autogenous mills—to achieve finer liberation sizes below 100–150 microns. Subsequent high-intensity magnetic separation or additional LIMS refines the product, yielding concentrates with iron grades typically exceeding 67% Fe and recoveries above 90% for magnetic fractions.[77][78] For ores with elevated silica content, reverse cationic flotation is employed post-magnetic separation to depress magnetite and float silica gangue using amines as collectors, reducing SiO₂ to below 3–5%. This technique is prevalent in operations in Australia and Brazil, major magnetite producers, facilitating the economic processing of taconite-like low-grade ores with initial Fe contents as low as 25–30%.[79][80] Although magnetite beneficiation demands higher energy for grinding and separation—up to 20–30 kWh/t more than hematite direct-shipping ores due to the need for extensive comminution—lifecycle assessments demonstrate that the resultant higher-grade concentrates (enabling pelletization) reduce overall energy intensity in downstream steelmaking by minimizing reductant use and slag volume.[81][82]Impurity Removal Techniques

Impurity removal in iron ore beneficiation targets gangue minerals including silica (SiO2), alumina (Al2O3), phosphorus (P), and sulfur (S), which elevate slag formation, flux requirements, and operational costs in smelting while risking steel defects such as brittleness from excess P or hot shortness from S.[83] Effective concentrates seek SiO2 below 2% and P under 0.1% to minimize downstream penalties in blast furnace pig iron production.[84][85] Thermal roasting oxidizes sulfide impurities at elevated temperatures, converting sulfur to volatile SO2 gas for removal, with applications extended to phosphorus-bearing ores via additives like CaO to achieve up to two-thirds P reduction through phase transformation and magnetic separation.[86][87] Though historically prevalent for sulfur volatilization, roasting has declined in favor of physical methods due to energy intensity but persists for refractory low-grade ores where chemical restructuring aids subsequent gangue rejection.[88][89] Froth flotation, often reverse flotation, employs collectors to float silica and alumina gangue, concentrating iron oxides in the underflow; this targets quartz impurities effectively in fines, with silica rejection rates exceeding 80% in optimized circuits.[90][91] Selective flocculation, prominent in Brazilian operations processing slimes from Quadrilátero Ferrífero deposits, uses polyacrylamide polymers to aggregate hematite particles while dispersing clays and silica, boosting Fe recovery to over 66% and reducing alumina via dispersion and settling.[92][93] Chemical leaching addresses persistent impurities like phosphorus and alumina through acid or alkali dissolution; sulfuric acid leaching removes up to 90% P from concentrates by solubilizing apatite phases, while combined alkali roasting-hydrothermal treatments reject Si, Al, and P gangue with efficiencies over 80% in low-grade slimes.[94][83] These hydrometallurgical approaches complement physical separation for ores where impurities are finely disseminated, though acid consumption and wastewater management limit scalability compared to flotation.[95][89]Smelting and Refining

Blast Furnace Smelting

In blast furnace smelting, iron ore—primarily hematite or magnetite in the form of sinter, pellets, or lump ore—is reduced to molten pig iron through a series of high-temperature chemical reactions driven by carbon monoxide derived from coke combustion. The furnace, a refractory-lined vertical shaft typically 20-40 meters tall, operates on a countercurrent principle: solid charge materials are fed from the top via a rotating chute or bell system, while preheated air (at 1000-1200°C) is injected at the bottom through tuyeres, reacting with coke to form CO₂ and CO. The primary reduction occurs via the Boudouard equilibrium (C + CO₂ ⇌ 2CO) and iron oxide reduction steps (e.g., 3Fe₂O₃ + CO → 2Fe₃O₄ + CO₂), progressing down the stack where temperatures rise from ~500°C at the top to over 1500°C in the bosh and hearth zones due to exothermic combustion and indirect heating. Limestone (CaCO₃) is added as flux, decomposing to CaO (quicklime) which combines with silica and alumina gangue from the ore to form molten slag (primarily CaSiO₃), facilitating separation from the iron.[96][97][98] The process requires approximately 1.5-2 tonnes of iron ore per tonne of pig iron produced, varying with ore grade (typically 55-65% Fe content) and burden preparation; for instance, high-grade pellets demand less input than lower-grade sinter blends. Coke consumption averages 300-400 kg per tonne of pig iron, providing both reductant and heat, while limestone flux input is around 200-400 kg to achieve optimal slag basicity (CaO/SiO₂ ratio of 1.0-1.2) for desulfurization and fluidity. Descent through the furnace takes 6-8 hours, with the reduced iron melting at ~1150-1200°C (lowered by dissolved carbon) to accumulate as pig iron (92-95% Fe, 3.5-4.5% C, with silicon, manganese, phosphorus, and sulfur impurities up to 1-2% each) in the hearth, tapped every 4-6 hours alongside slag.[99][100][101] Thermodynamically, the process relies on the exothermic oxidation of carbon (ΔH ≈ -394 kJ/mol for C + O₂ → CO₂) to supply heat for endothermic reduction (e.g., FeO + CO → Fe + CO₂, ΔH ≈ +16 kJ/mol) and melting, achieving thermal efficiency through gas recycling via top-gas recovery for preheating. The blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) route dominates global primary ironmaking, accounting for over 70% of crude steel production as of 2023, due to its scalability and ability to handle diverse ore types for high-volume output essential to infrastructure steels.[102][103]Direct Reduction Alternatives

Direct reduction processes produce sponge iron, or direct reduced iron (DRI), by removing oxygen from iron ore pellets or lumps using reducing agents such as natural gas-derived syngas, coal, or hydrogen, operating at temperatures below the iron melting point to avoid slag formation.[104] The Midrex process, which employs a shaft furnace with reformed natural gas (primarily hydrogen and carbon monoxide) as the reductant, dominates commercial DRI production, achieving metallization rates of 93-96% and capacities up to 2.5 million tons per module.[104] Coal-based variants, common in India and China, use rotary kilns or retorts but yield lower-quality DRI with higher impurities and emissions.[105] Global DRI production reached 140.8 million metric tons in 2024, an increase of 3.8% from 2023, primarily driven by expansions in India (54.7 million tons) and Iran (34.7 million tons), though this constitutes only about 7.5% of total primary iron output amid dominance of blast furnace routes.[106] Natural gas-based DRI emits roughly 0.5-1.0 tons of CO2 per ton of iron, a 40-60% reduction compared to blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) routes emitting 1.8-2.0 tons, due to avoidance of coke and reliance on gaseous reductants; coal-based DRI achieves only a 38% reduction owing to inherent carbon use.[105] Hydrogen-based direct reduction (H2-DRI) can approach near-zero process emissions if powered by renewable electricity, as demonstrated in pilots, but requires pure hydrogen to prevent reoxidation and maintain product quality.[107] Emerging hydrogen initiatives, such as Sweden's HYBRIT project—a collaboration between SSAB, LKAB, and Vattenfall—produced the world's first fossil-free steel billet from H2-DRI in 2021 using a pilot shaft furnace in Luleå, with a demonstration plant targeting 1.5 million tons annually by the late 2020s; by 2025, hydrogen storage pilots confirmed technical feasibility for intermittent renewable supply but highlighted scaling needs for gigawatt-scale electrolysis.[108] The resulting sponge iron is melted in electric arc furnaces (EAFs) alongside scrap, enabling flexible low-carbon steelmaking, though EAF routes remain ore-limited without sufficient DRI or high-quality scrap, which comprised only 30-40% of global steel input in 2024.[109] Despite lower emissions potential, H2-DRI viability hinges on subsidies and cost declines, with production expenses estimated at $500-600 per ton in 2024 versus $400-450 for traditional BF-BOF, driven by hydrogen prices exceeding $4-6 per kg without scale; competitiveness demands green hydrogen below $1.5-2 per kg, unachievable broadly absent massive renewable overbuilds.[110] Scalability faces empirical barriers, including scarcity of direct reduction-grade iron ore (requiring >67% Fe, <2% silica/alumina for high metallization without agglomeration issues), projected shortages by 2030 as demand surges, and infrastructure for hydrogen transport, limiting deployment to niche, subsidized applications rather than wholesale replacement of established BF capacity.[111][112][113]Handling Trace Elements