Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

United States dollar

View on Wikipedia

Federal Reserve Notes (obverse) | |

| ISO 4217 | |

|---|---|

| Code | USD (numeric: 840) |

| Subunit | 0.01 |

| Unit | |

| Symbol | $, US$, U$ |

| Nickname | List

|

| Denominations | |

| Superunit | |

| 10 | Eagle |

| 100 | Union (Proposed, never issued) |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄10 | Dime |

| 1⁄100 | Cent |

| 1⁄1000 | Mill |

| Symbol | |

| Cent | ¢ |

| Mill | ₥ |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | $1, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100 |

| Rarely used | $2 (still printed); $500, $1,000, $5,000, $10,000 (discontinued, but still legal tender); $100,000 (discontinued, not legal tender, and only used for specific purposes) |

| Coins | |

| Freq. used | 1¢, 5¢, 10¢, 25¢ |

| Rarely used | 50¢, $1 (still minted); 1⁄2¢, 2¢, 3¢, 20¢, $2.50, $3, $5, $10, $20 (discontinued, but still legal tender); $25, $50, $100 (not intended for circulation) |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | April 2, 1792[1] |

| Replaced | Continental currency Various foreign currencies, including: Pound sterling Spanish dollar |

| User(s) | See § Official users (19), § Unofficial users (8) |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Federal Reserve |

| Website | federalreserve.gov |

| Printer | Bureau of Engraving and Printing |

| Website | bep.gov |

| Mint | United States Mint |

| Website | usmint.gov |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 3.0% or 2.7% |

| Source | BLS (September 2025) or BEA (August 2025) |

| Method | CPI or PCE |

| Pegged by | See § Pegged currencies |

The United States dollar (symbol: $; currency code: USD[a]) is the official currency of the United States and several other countries. The Coinage Act of 1792 introduced the U.S. dollar at par with the Spanish silver dollar, divided it into 100 cents, and authorized the minting of coins denominated in dollars and cents. U.S. banknotes are issued in the form of Federal Reserve Notes, popularly called greenbacks due to their predominantly green color.

The U.S. dollar was originally defined under a bimetallic standard of 371.25 grains (24.057 g) (0.7734375 troy ounces) fine silver or, from 1834,[2] 23.22 grains (1.505 g) fine gold, or $20.67 per troy ounce. The Gold Standard Act of 1900 linked the dollar solely to gold. From 1934, its equivalence to gold was revised to $35 per troy ounce. In 1971 all links to gold were repealed.[3] The U.S. dollar became an important international reserve currency after the First World War, and displaced the pound sterling as the world's primary reserve currency by the Bretton Woods Agreement towards the end of the Second World War. The dollar is the most widely used currency in international transactions,[4] and a free-floating currency. It is also the official currency in several countries and the de facto currency in many others,[5][6] with Federal Reserve Notes (and, in a few cases, U.S. coins) used in circulation.

The monetary policy of the United States is conducted by the Federal Reserve System, which acts as the nation's central bank. As of February 10, 2021, currency in circulation amounted to US$2.10 trillion, $2.05 trillion of which is in Federal Reserve Notes (the remaining $50 billion is in the form of coins and older-style United States Notes).[7][failed verification] As of January 1, 2025, the Federal Reserve estimated that the total amount of currency in circulation was approximately US$2.37 trillion.[8]

Overview

[edit]In the Constitution

[edit]Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution provides that Congress has the power "to coin money".[9] Laws implementing this power are currently codified in Title 31 of the U.S. Code, under Section 5112, which prescribes the forms in which the United States dollars should be issued.[10] These coins are both designated in the section as legal tender in payment of debts.[11] The Sacagawea dollar is one example of the copper alloy dollar, in contrast to the American Silver Eagle which is pure silver. Section 5112 also provides for the minting and issuance of other coins, which have values ranging from one cent (U.S. Penny) to 100 dollars.[11] These other coins are more fully described in Coins of the United States dollar.

Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution provides that "a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time",[12] which is further specified by Section 331 of Title 31 of the U.S. Code.[13] The sums of money reported in the "Statements" are currently expressed in U.S. dollars, thus the U.S. dollar may be described as the unit of account of the United States.[14] "Dollar" is one of the first words of Section 9, in which the term refers to the Spanish milled dollar, or the coin worth eight Spanish reales.

Coinage Act

[edit]In 1792, the U.S. Congress passed the Coinage Act, of which Section 9 authorized the production of various coins, including:[15]: 248

Dollars or Units—each to be of the value of a Spanish milled dollar as the same is now current, and to contain three hundred and seventy-one grains and four sixteenth parts of a grain of pure, or four hundred and sixteen grains of standard silver.

Section 20 of the Act designates the United States dollar as the unit of currency of the United States:[16]: 250–1

[T]he money of account of the United States shall be expressed in dollars, or units...and that all accounts in the public offices and all proceedings in the courts of the United States shall be kept and had in conformity to this regulation.

Decimal units

[edit]Unlike the Spanish milled dollar, the Continental Congress and the Coinage Act prescribed a decimal system of units to go with the unit dollar, as follows:[17][18] the mill, or one-thousandth of a dollar; the cent, or one-hundredth of a dollar; the dime, or one-tenth of a dollar; and the eagle, or ten dollars. The current relevance of these units:

- Only the cent (¢) is used as an everyday division of the dollar, with the ubiquitous exception of vehicle fuel pricing.

- Dime is used solely as the name of the coin with the value of ten cents.

- The mill (₥) is relatively unknown but before the middle of the 20th century was familiar in matters of sales taxes. It is ubiquitous in prices of gasoline and diesel fuels, which are usually in the form of $xx.xx9 per gallon (e.g., $3.599, commonly written as $3.59+9⁄10).[19][20]

- The eagle is also largely unknown to the general public.[20] This term was used in the Coinage Act of 1792 for the denomination of ten dollars and subsequently in naming gold coins.

The Spanish peso, or dollar, was historically divided into eight reales (colloquially, bits) – hence pieces of eight. Americans also learned counting in non-decimal bits of 12+1⁄2 cents before 1857 when Mexican bits were more frequently encountered than American cents; in fact this practice survived in New York Stock Exchange quotations until 2001.[21][22]

In 1854, Secretary of the Treasury James Guthrie proposed creating $100, $50, and $25 gold coins, to be referred to as a union, half union, and quarter union, respectively,[23] thus implying a denomination of 1 Union = $100. However, no such coins were ever struck, and only patterns for the $50 half union exist.

When currently issued in circulating form, denominations less than or equal to a dollar are emitted as U.S. coins, while denominations greater than or equal to a dollar are emitted as Federal Reserve Notes, disregarding the following special cases:

- Gold coins issued for circulation until the 1930s, up to the value of $20 (known as the double eagle)

- Bullion or commemorative gold, silver, platinum, and palladium coins valued up to $100 as legal tender (though worth far more as bullion).

- Civil War paper currency issue in denominations below $1, i.e. fractional currency, sometimes pejoratively referred to as shinplasters.

Etymology

[edit]In the 16th century, Count Hieronymus Schlick of Bohemia began minting coins known as joachimstalers, named for Joachimstal, the valley in which the silver was mined. In turn, the valley's name is titled after Saint Joachim, whereby thal or tal, a cognate of the English word dale, is German for 'valley.'[24] The joachimstaler was later shortened to the German taler, a word that eventually found its way into many languages, including:[24] tolar (Czech, Slovak and Slovenian); daler (Danish and Swedish); talar (Polish); dalar and daler (Norwegian); daler or daalder (Dutch); talari (Ethiopian); tallér (Hungarian); tallero (Italian); دولار (Arabic); and dollar (English).

Though the Dutch pioneered in modern-day New York in the 17th century the use and the counting of money in silver dollars in the form of German-Dutch reichsthalers and native Dutch leeuwendaalders ('lion dollars'), it was the ubiquitous Spanish American eight-real coin which became exclusively known as the dollar since the 18th century.[25]

Nicknames

[edit]The colloquialism buck(s) (much like the British quid for the pound sterling) is often used to refer to dollars of various nations, including the U.S. dollar. This term, dating to the 18th century, may have originated with the colonial leather trade, or it may also have originated from a poker term.[26]

Greenback is another nickname, originally applied specifically to the 19th-century Demand Note dollars, which were printed black and green on the backside, created by Abraham Lincoln to finance the North for the Civil War.[27] It is still used to refer to the U.S. dollar (but not to the dollars of other countries). The term greenback is also used by the financial press in other countries, such as Australia,[28] New Zealand,[29] South Africa,[30] and India.[31]

Other well-known names of the dollar as a whole in denominations include greenmail, green, and dead presidents, the latter of which referring to the deceased presidents pictured on most bills. Dollars in general have also been known as bones (e.g. "twenty bones" = $20). The newer designs, with portraits displayed in the main body of the obverse (rather than in cameo insets), upon paper color-coded by denomination, are sometimes referred to as bigface notes or Monopoly money.[citation needed]

Piastre was the original French word for the U.S. dollar, used for example in the French text of the Louisiana Purchase. Though the U.S. dollar is called dollar in Modern French, the term piastre is still used among the speakers of Cajun French and New England French, as well as speakers in Haiti and other French Caribbean islands.

Nicknames specific to denomination:

- The quarter dollar coin is known as two bits, alluding the dollar's origins as the "piece of eight" (bits or reales).[21]

- The $1 bill is nicknamed buck or single.

- The infrequently used $2 bill is sometimes called deuce, Tom, or Jefferson (after Thomas Jefferson).

- The $5 bill is sometimes called Lincoln (after Abraham Lincoln), fin, fiver, or five-spot.

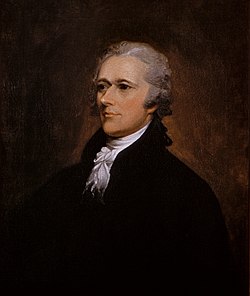

- The $10 bill is sometimes called sawbuck, ten-spot, or Hamilton (after Alexander Hamilton).

- The $20 bill is sometimes called double sawbuck, Jackson (after Andrew Jackson), or double eagle.

- The $50 bill is sometimes called a yardstick, or a grant, after President Ulysses S. Grant.

- The $100 bill is called Benjamin, Benji, Ben, or Franklin, referring to its portrait of Benjamin Franklin. Other nicknames include C-note (C being the Roman numeral for 100), century note, or bill (e.g. two bills = $200).

- Amounts or multiples of $1,000 are sometimes called grand in colloquial speech, abbreviated in written form to G, K, or k (from kilo; e.g. $10k = $10,000). Likewise, a large or stack can also refer to a multiple of $1,000 (e.g. "fifty large" = $50,000).

Dollar sign

[edit]

The symbol $, usually written before the numerical amount, is used for the U.S. dollar (as well as for many other currencies). The sign was perhaps the result of a late 18th-century evolution of the scribal abbreviation ps for the peso, the common name for the Spanish dollars that were in wide circulation in the New World from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The p and the s eventually came to be written over each other giving rise to $.[32][33][34][35]

Another popular explanation is that it is derived from the Pillars of Hercules on the Spanish coat of arms of the Spanish dollar. These Pillars of Hercules on the silver Spanish dollar coins take the form of two vertical bars (||) and a swinging cloth band in the shape of an S.[36]

Yet another explanation suggests that the dollar sign was formed from the capital letters U and S written or printed one on top of the other. This theory, popularized by novelist Ayn Rand in Atlas Shrugged,[37] does not consider the fact that the symbol was already in use before the formation of the United States.[38]

History

[edit]Origins: the Spanish dollar

[edit]The U.S. dollar was introduced at par with the Spanish-American silver dollar (or Spanish peso, Spanish milled dollar, eight-real coin, piece-of-eight). The latter was produced from the rich silver mine output of Spanish America, was minted in Mexico City, Potosí (Bolivia), Lima (Peru), and elsewhere, and was in wide circulation throughout the Americas, Asia, and Europe from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The minting of machine-milled Spanish dollars since 1732 boosted its worldwide reputation as a trade coin and positioned it to be the model for the new currency of the United States.[citation needed]

Even after the United States Mint commenced issuing coins in 1792, locally minted dollars and cents were less abundant in circulation than Spanish American pesos and reales; hence Spanish, Mexican, and American dollars all remained legal tender in the United States until the Coinage Act of 1857. In particular, colonists' familiarity with the Spanish two-real quarter peso was the reason for issuing a quasi-decimal 25-cent quarter dollar coin rather than a 20-cent coin.[citation needed]

For the relationship between the Spanish dollar and the individual state colonial currencies, see Connecticut pound, Delaware pound, Georgia pound, Maryland pound, Massachusetts pound, New Hampshire pound, New Jersey pound, New York pound, North Carolina pound, Pennsylvania pound, Rhode Island pound, South Carolina pound, and Virginia pound.[citation needed]

Coinage Act of 1792

[edit]

On July 6, 1785, the Continental Congress resolved that the money unit of the United States, the dollar, would contain 375.64 grains of fine silver; on August 8, 1786, the Continental Congress continued that definition and further resolved that the money of account, corresponding with the division of coins, would proceed in a decimal ratio, with the sub-units being mills at 0.001 of a dollar, cents at 0.010 of a dollar, and dimes at 0.100 of a dollar.[17]

After the adoption of the United States Constitution, the U.S. dollar was defined by the Coinage Act of 1792. It specified a "dollar" based on the Spanish milled dollar to contain 371+4⁄16 grains of fine silver, or 416.0 grains (26.96 g) of "standard silver" of fineness 371.25/416 = 89.24%; as well as an "eagle" to contain 247+4⁄8 grains of fine gold, or 270.0 grains (17.50 g) of 22 karat or 91.67% fine gold.[39] Alexander Hamilton arrived at these numbers based on a treasury assay of the average fine silver content of a selection of worn Spanish dollars, which came out to be 371 grains. Combined with the prevailing gold-silver ratio of 15, the standard for gold was calculated at 371/15 = 24.73 grains fine gold or 26.98 grains 22K gold. Rounding the latter to 27.0 grains finalized the dollar's standard to 24.75 grains of fine gold or 24.75 × 15 = 371.25 grains = 24.0566 grams = 0.7735 troy ounces of fine silver.

The same coinage act also set the value of an eagle at 10 dollars, and the dollar at 1⁄10 eagle. It called for silver coins in denominations of 1, 1⁄2, 1⁄4, 1⁄10, and 1⁄20 dollar, as well as gold coins in denominations of 1, 1⁄2 and 1⁄4 eagle. The value of gold or silver contained in the dollar was then converted into relative value in the economy for the buying and selling of goods. This allowed the value of things to remain fairly constant over time, except for the influx and outflux of gold and silver in the nation's economy.[40]

Though a Spanish dollar freshly minted after 1772 theoretically contained 417.7 grains of silver of fineness 130/144 (or 377.1 grains fine silver), reliable assays of the period in fact confirmed a fine silver content of 370.95 grains (24.037 g) for the average Spanish dollar in circulation.[41] The new U.S. silver dollar of 371.25 grains (24.057 g) therefore compared favorably and was received at par with the Spanish dollar for foreign payments, and after 1803 the United States Mint had to suspend making this coin out of its limited resources since it failed to stay in domestic circulation. It was only after Mexican independence in 1821 when their peso's fine silver content of 377.1 grains was firmly upheld, which the U.S. later had to compete with using a heavier 378.0 grains (24.49 g) Trade dollar coin.

Design

[edit]The early currency of the United States did not exhibit faces of presidents, as is the custom now;[42] although today, by law, only the portrait of a deceased individual may appear on United States currency.[43] In fact, the newly formed government was against having portraits of leaders on the currency, a practice compared to the policies of European monarchs.[44] The currency as we know it today did not get the faces they currently have until after the early 20th century; before that "heads" side of coinage used profile faces and striding, seated, and standing figures from Greek and Roman mythology and composite Native Americans. The last coins to be converted to profiles of historic Americans were the dime (1946), the half Dollar (1948), and the Dollar (1971).

Continental currency

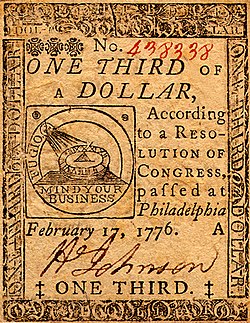

[edit]

After the American Revolution, the Thirteen Colonies became independent. Freed from British monetary regulations, they each issued £sd paper money to pay for military expenses. The Continental Congress also began issuing "Continental Currency" denominated in Spanish dollars. For its value relative to states' currencies, see Early American currency.

Continental currency depreciated badly during the war, giving rise to the famous phrase "not worth a continental".[45] A primary problem was that monetary policy was not coordinated between Congress and the states, which continued to issue bills of credit. Additionally, neither Congress nor the governments of the several states had the will or the means to retire the bills from circulation through taxation or the sale of bonds.[46] The currency was ultimately replaced by the silver dollar at the rate of 1 silver dollar to 1000 continental dollars. This resulted in the clause "No state shall... make anything but gold and silver coin a tender in payment of debts" being written into the United States Constitution article 1, section 10.

Silver and gold standards, 19th century

[edit]From implementation of the 1792 Mint Act to the 1900 implementation of the gold standard, the dollar was on a bimetallic silver-and-gold standard, defined as either 371.25 grains (24.056 g) of fine silver or 24.75 grains of fine gold (gold-silver ratio 15).

Subsequent to the Coinage Act of 1834 the dollar's fine gold equivalent was revised to 23.2 grains; it was slightly adjusted to 23.22 grains (1.505 g) in 1837 (gold-silver ratio ≈16). The same act also resolved the difficulty in minting the "standard silver" of 89.24% fineness by revising the dollar's alloy to 412.5 grains, 90% silver, still containing 371.25 grains fine silver. Gold was also revised to 90% fineness: 25.8 grains gross, 23.22 grains fine gold.

Following the rise in the price of silver during the California Gold Rush and the disappearance of circulating silver coins, the Coinage Act of 1853 reduced the standard for silver coins less than $1 from 412.5 grains to 384 grains (24.9 g), 90% silver per 100 cents (slightly revised to 25.0 g, 90% silver in 1873). The Act also limited the free silver right of individuals to convert bullion into only one coin, the silver dollar of 412.5 grains; smaller coins of lower standard can only be produced by the United States Mint using its own bullion.

Summary and links to coins issued in the 19th century:

- In base metal: 1/2 cent, 1 cent, 5 cents.

- In silver: half dime, dime, quarter dollar, half dollar, silver dollar.

- In gold: gold $1, $2.50 quarter eagle, $5 half eagle, $10 eagle, $20 double eagle.

- Less common denominations: bronze 2 cents, nickel 3 cents, silver 3 cents, silver 20 cents, gold $3.

Note issues, 19th century

[edit]

In order to finance the War of 1812, Congress authorized the issuance of Treasury Notes, interest-bearing short-term debt that could be used to pay public dues. While they were intended to serve as debt, they did function "to a limited extent" as money. Treasury Notes were again printed to help resolve the reduction in public revenues resulting from the Panic of 1837 and the Panic of 1857, as well as to help finance the Mexican–American War and the Civil War.

Paper money was issued again in 1862 without the backing of precious metals due to the Civil War. In addition to Treasury Notes, Congress in 1861 authorized the Treasury to borrow $50 million in the form of Demand Notes, which did not bear interest but could be redeemed on demand for precious metals. However, by December 1861, the Union government's supply of specie was outstripped by demand for redemption and they were forced to suspend redemption temporarily. In February 1862 Congress passed the Legal Tender Act of 1862, issuing United States Notes, which were not redeemable on demand and bore no interest, but were legal tender, meaning that creditors had to accept them at face value for any payment except for import tariffs and interest on public debts. However, silver and gold coins continued to be issued, resulting in the depreciation of the newly printed notes through Gresham's law. In 1869, the Supreme Court ruled in Hepburn v. Griswold that Congress could not require creditors to accept United States Notes, but overturned that ruling the next year in the Legal Tender Cases. In 1875, Congress passed the Specie Payment Resumption Act, requiring the Treasury to allow U.S. Notes to be redeemed for gold after January 1, 1879.

Gold standard, 20th century

[edit]

Though the dollar came under the gold standard de jure only after 1900, the bimetallic era was ended de facto when the Coinage Act of 1873 suspended the minting of the standard silver dollar of 412.5 Troy grains = 26.73 g; 0.859 ozt, the only fully legal tender coin that individuals could convert bullion into in unlimited (or Free silver) quantities,[b] and right at the onset of the silver rush from the Comstock Lode in the 1870s. This was the so-called "Crime of '73".

The Gold Standard Act of 1900 repealed the U.S. dollar's historic link to silver and defined it solely as 23.22 grains (1.505 g) of fine gold (or $20.67 per troy ounce of 480 grains). In 1933, gold coins were confiscated by Executive Order 6102 under Franklin D. Roosevelt, and in 1934 the standard was changed to $35 per troy ounce fine gold, or 13.71 grains (0.888 g) per dollar.

After 1968 a series of revisions to the gold peg was implemented, culminating in the Nixon Shock of August 15, 1971, which suddenly ended the convertibility of dollars to gold. The U.S. dollar has since floated freely on the foreign exchange markets.[citation needed]

Federal Reserve Notes, 20th century to present

[edit]Congress continued to issue paper money after the Civil War, the latest of which is the Federal Reserve Note that was authorized by the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. Since the discontinuation of all other types of notes (Gold Certificates in 1933, Silver Certificates in 1963, and United States Notes in 1971), U.S. dollar notes have since been issued exclusively as Federal Reserve Notes.

Emergence as reserve currency

[edit]

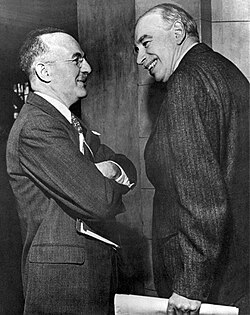

The U.S. dollar first emerged as an important international reserve currency in the 1920s, displacing the British pound sterling as it emerged from the First World War relatively unscathed and since the United States was a significant recipient of wartime gold inflows. After the United States emerged as an even stronger global superpower during the Second World War, the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944 established the U.S. dollar as the world's primary reserve currency and the only post-war currency linked to gold. Despite all links to gold being severed in 1971, the dollar continues to be the world's foremost reserve currency for international trade to this day.

The Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944 also defined the post-World War II monetary order and relations among modern-day independent states, by setting up a system of rules, institutions, and procedures to regulate the international monetary system. The agreement founded the International Monetary Fund and other institutions of the modern-day World Bank Group, establishing the infrastructure for conducting international payments and accessing the global capital markets using the U.S. dollar.

The monetary policy of the United States is conducted by the Federal Reserve System, which acts as the nation's central bank. It was founded in 1913 under the Federal Reserve Act in order to furnish an elastic currency for the United States and to supervise its banking system, particularly in the aftermath of the Panic of 1907.

For most of the post-war period, the U.S. government has financed its own spending by borrowing heavily from the dollar-lubricated global capital markets, in debts denominated in its own currency and at minimal interest rates. This ability to borrow heavily without facing a significant balance of payments crisis has been described as the United States's exorbitant privilege.

Coins

[edit]The United States Mint has issued legal tender coins every year from 1792 to the present. From 1934 to the present, the only denominations produced for circulation have been the familiar penny, nickel, dime, quarter, half dollar, and dollar.

| Denomination | Common name | Obverse | Reverse | Obverse portrait and design date | Reverse motif and design date | Weight | Diameter | Material | Edge | Circulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cent 1¢ |

penny | Abraham Lincoln (1909) | Union Shield (2010) | 2.5 g (0.088 oz) |

0.75 in (19.05 mm) |

97.5% Zn covered by 2.5% Cu | Plain | Wide | ||

| Five cents 5¢ |

nickel |

|

|

Thomas Jefferson (2006) | Monticello (1938) | 5.0 g (0.176 oz) |

0.835 in (21.21 mm) |

75% Cu 25% Ni |

Plain | Wide |

| Ten cents 10¢ |

dime | Franklin D. Roosevelt (1946) | Olive branch, torch, and oak branch (1946) | 2.268 g (0.08 oz) |

0.705 in (17.91 mm) |

91.67% Cu 8.33% Ni |

118 reeds | Wide | ||

| Quarter dollar 25¢ |

quarter |

|

|

George Washington (1932) | Various (5 designs per year) | 5.67 g (0.2 oz) |

0.955 in (24.26 mm) |

91.67% Cu 8.33% Ni |

119 reeds | Wide |

| Half dollar 50¢ |

half dollar |

|

|

John F. Kennedy (1964) | Presidential Seal (1964) | 11.34 g (0.4 oz) |

1.205 in (30.61 mm) |

91.67% Cu 8.33% Ni |

150 reeds | Limited |

| Dollar coin $1 |

dollar coin, golden dollar |

|

|

Sacagawea

(2000) |

Various (4 designs per year) | 8.10 g (0.286 oz) |

1.043 in (26.50 mm) |

88.5% Cu 6% Zn 3.5% Mn 2% Ni |

Plain 2000–2006 Lettered 2007–Present |

Limited |

| These images are to scale at 2.5 pixels per millimetre. For table standards, see the coin specification table. | ||||||||||

Gold and silver coins have been previously minted for general circulation from the 18th to the 20th centuries. The last gold coins were minted in 1933. The last 90% silver coins were minted in 1964, and the last 40% silver half dollar was minted in 1970.

The United States Mint currently produces circulating coins at the Philadelphia and Denver Mints, and commemorative and proof coins for collectors at the San Francisco and West Point Mints. Mint mark conventions for these and for past mint branches are discussed in Coins of the United States dollar#Mint marks.

The one-dollar coin has never been in popular circulation from 1794 to present, despite several attempts to increase their usage since the 1970s, the most important reason of which is the continued production and popularity of the one-dollar bill.[47] Half dollar coins were commonly used currency since inception in 1794, but has fallen out of use from the mid-1960s when all silver half dollars began to be hoarded.

The nickel is the only coin whose size and composition (5 grams, 75% copper, and 25% nickel) is still in use from 1865 to today, except for wartime 1942–1945 Jefferson nickels which contained silver.

Due to the penny's low value, some debate exists over the penny's status as circulating coinage.[48][49]

For a discussion of other discontinued and canceled denominations, see Obsolete denominations of United States currency and Canceled denominations of United States currency.

Collector coins

[edit]Collector coins are technically legal tender at face value but are usually worth far more due to their numismatic value or for their precious metal content. These include:

- American Eagle bullion coins

- American Silver Eagle $1 (1 troy oz) Silver bullion coin 1986–present

- American Gold Eagle $5 (1⁄10 troy oz), $10 (1⁄4 troy oz), $25 (1⁄2 troy oz), and $50 (1 troy oz) Gold bullion coin 1986–present

- American Platinum Eagle $10 (1⁄10 troy oz), $25 (1⁄4 troy oz), $50 (1⁄2 troy oz), and $100 (1 troy oz) Platinum bullion coin 1997–present

- American Palladium Eagle $25 (1 troy oz) Palladium bullion coin 2017–present

- United States commemorative coins—special issue coins, among these:

- $50.00 (Half Union) minted for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (1915)

- Silver proof sets minted since 1992 with dimes, quarters and half-dollars made of silver rather than the standard copper-nickel

- Presidential dollar coins proof sets minted since 2007

Banknotes

[edit]| Denomination | Obverse | Reverse | Portrait | Reverse motif | First series | Latest series | Circulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One dollar |

|

|

George Washington | Great Seal of the United States | Series 1963[c] Series 1935[d] |

Series 2021[50] | Wide |

| Two dollars |

|

|

Thomas Jefferson | Declaration of Independence by John Trumbull | Series 1976 | Series 2017A | Limited[51] |

| Five dollars |

|

|

Abraham Lincoln | Lincoln Memorial | Series 2006 | Series 2021[52] | Wide |

| Ten dollars |

|

|

Alexander Hamilton | Treasury Building | Series 2004A | Series 2021 | Wide |

| Twenty dollars |

|

|

Andrew Jackson | White House | Series 2004 | Series 2017A | Wide |

| Fifty dollars |

|

|

Ulysses S. Grant | United States Capitol | Series 2004 | Series 2017A | Wide |

| One hundred dollars |

|

|

Benjamin Franklin | Independence Hall | Series 2009A[53] | Series 2021 | Wide |

The U.S. Constitution provides that Congress shall have the power to "borrow money on the credit of the United States."[54] Congress has exercised that power by authorizing Federal Reserve Banks to issue Federal Reserve Notes. Those notes are "obligations of the United States" and "shall be redeemed in lawful money on demand at the Treasury Department of the United States, in the city of Washington, District of Columbia, or at any Federal Reserve bank".[55] Federal Reserve Notes are designated by law as "legal tender" for the payment of debts.[56] Congress has also authorized the issuance of more than 10 other types of banknotes, including the United States Note[57] and the Federal Reserve Bank Note. The Federal Reserve Note is the only type that remains in circulation since the 1970s. Federal Reserve Notes are printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and are made from cotton fiber paper (as opposed to wood fiber used to make common paper). The "large-sized notes" issued before 1928 measured 7.42 in × 3.125 in (188.5 mm × 79.4 mm), while small-sized notes introduced that year measure 6.14 in × 2.61 in × 0.0043 in (155.96 mm × 66.29 mm × 0.11 mm).[58] The dimensions of the modern (small-size) U.S. currency is identical to the size of Philippine peso banknotes issued under United States administration after 1903, which had proven highly successful.[59] The American large-note bills became known as "horse blankets" or "saddle blankets".[60]

Currently printed denominations are $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100. Notes above the $100 denomination stopped being printed in 1946 and were officially withdrawn from circulation in 1969. These notes were used primarily in inter-bank transactions or by organized crime; it was the latter usage that prompted President Richard Nixon to issue an executive order in 1969 halting their use. With the advent of electronic banking, they became less necessary. Notes in denominations of $500, $1,000, $5,000, $10,000 (discontinued, but still legal tender); $100,000 were all produced at one time; see large denomination bills in U.S. currency for details. With the exception of the $100,000 bill (which was only issued as a Series 1934 Gold Certificate and was never publicly circulated; thus it is illegal to own), these notes are now collector's items and are worth more than their face value to collectors.

Though still predominantly green, the post-2004 series incorporate other colors to better distinguish different denominations. As a result of a 2008 decision in an accessibility lawsuit filed by the American Council of the Blind, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing is planning to implement a raised tactile feature in the next redesign of each note, except the $1 and the current version of the $100 bill. It also plans larger, higher-contrast numerals, more color differences, and distribution of currency readers to assist the visually impaired during the transition period.[e]

Countries that use US dollar

[edit]Official users

[edit]These countries and territories use the US dollar as the official currency:

United States

United States

- including 5 territories:

- United States Minor Outlying Islands

- Compact of Free Association

Ecuador[61]

Ecuador[61]

(alongside Ecuadorian centavo coins) El Salvador[62]

El Salvador[62] Liberia[63]

Liberia[63]

(alongside Liberian dollar) Panama

Panama

(alongside Panamanian balboa coins) Timor-Leste[64]

Timor-Leste[64]

(alongside Timor-Leste centavo coins)- British Overseas Territories:

- Dutch Caribbean:

Unofficial users

[edit]These countries and territories widely accept the US dollar unofficially as a secondary currency:

Argentina, official currency is Argentine peso

Argentina, official currency is Argentine peso Cambodia,[65][66] official currency is Cambodian riel

Cambodia,[65][66] official currency is Cambodian riel Honduras, official currency is Honduran lempira[67]

Honduras, official currency is Honduran lempira[67] Lebanon, official currency is Lebanese pound[68]

Lebanon, official currency is Lebanese pound[68] Venezuela, official currency is Venezuelan bolívar[69][70]

Venezuela, official currency is Venezuelan bolívar[69][70] Zimbabwe, official currency is Zimbabwean ZiG

Zimbabwe, official currency is Zimbabwean ZiG- British Overseas Territories:

British Indian Ocean Territory, official currency is the Pound sterling

British Indian Ocean Territory, official currency is the Pound sterling

- Dutch Caribbean:

Sint Maarten, official currency is Caribbean guilder

Sint Maarten, official currency is Caribbean guilder

- Overseas France:

Saint Martin, official currency is the euro

Saint Martin, official currency is the euro

Monetary policy

[edit]

The Federal Reserve Act created the Federal Reserve System in 1913 as the central bank of the United States. Its primary task is to conduct the nation's monetary policy to promote maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates in the U.S. economy. It is also tasked to promote the stability of the financial system and regulate financial institutions, and to act as lender of last resort.[71][72]

The Monetary policy of the United States is conducted by the Federal Open Market Committee, which is composed of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and 5 out of the 12 Federal Reserve Bank presidents, and is implemented by all twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks.

Monetary policy refers to actions made by central banks that determine the size and growth rate of the money supply available in the economy, and which would result in desired objectives like low inflation, low unemployment, and stable financial systems. The economy's aggregate money supply is the total of

- M0 money, or Monetary Base – "dollars" in currency and bank money balances credited to the central bank's depositors, which are backed by the central bank's assets,

- plus M1, M2, M3 money – "dollars" in the form of bank money balances credited to banks' depositors, which are backed by the bank's assets and investments.

The FOMC influences the level of money available to the economy by the following means:

- Reserve requirements – specifies a required minimum percentage of deposits in a commercial bank that should be held as a reserve (i.e. as deposits with the Federal Reserve), with the rest available to loan or invest. Higher requirements mean less money loaned or invested, helping keep inflation in check. Raising the federal funds rate earned on those reserves also helps achieve this objective.

- Open market operations – the Federal Reserve buys or sells US Treasury bonds and other securities held by banks in exchange for reserves; more reserves increase a bank's capacity to loan or invest elsewhere.

- Discount window lending – banks can borrow from the Federal Reserve.

Monetary policy directly affects interest rates; it indirectly affects stock prices, wealth, and currency exchange rates. Through these channels, monetary policy influences spending, investment, production, employment, and inflation in the United States. Effective monetary policy complements fiscal policy to support economic growth.

The adjusted monetary base has increased from approximately $400 billion in 1994, to $800 billion in 2005, and to over $3 trillion in 2013.[73]

When the Federal Reserve makes a purchase, it credits the seller's reserve account (with the Federal Reserve). This money is not transferred from any existing funds—it is at this point that the Federal Reserve has created new high-powered money. Commercial banks then decide how much money to keep in deposit with the Federal Reserve and how much to hold as physical currency. In the latter case, the Federal Reserve places an order for printed money from the U.S. Treasury Department.[74] The Treasury Department, in turn, sends these requests to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (to print new dollar bills) and the Bureau of the Mint (to stamp the coins).

The Federal Reserve's monetary policy objectives to keep prices stable and unemployment low is often called the dual mandate. This replaces past practices under a gold standard where the main concern is the gold equivalent of the local currency, or under a gold exchange standard where the concern is fixing the exchange rate versus another gold-convertible currency (previously practiced worldwide under the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944 via fixed exchange rates to the U.S. dollar).

International use as reserve currency

[edit]

Ascendancy

[edit]The primary currency used for global trade between Europe, Asia, and the Americas has historically been the Spanish-American silver dollar, which created a global silver standard system from the 16th to 19th centuries, due to abundant silver supplies in Spanish America.[75] The U.S. dollar itself was derived from this coin. The Spanish dollar was later displaced by the British pound sterling in the advent of the international gold standard in the last quarter of the 19th century.

The U.S. dollar began to displace the pound sterling as international reserve currency from the 1920s since it emerged from the First World War relatively unscathed and since the United States was a significant recipient of wartime gold inflows.[76] After the U.S. emerged as an even stronger global superpower during the Second World War, the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944 established the post-war international monetary system, with the U.S. dollar ascending to become the world's primary reserve currency for international trade, and the only post-war currency linked to gold at $35 per troy ounce.[77]

As international reserve currency

[edit]The U.S. dollar is joined by the world's other major currencies – the euro, pound sterling, Japanese yen and Chinese renminbi – in the currency basket of the special drawing rights of the International Monetary Fund. Central banks worldwide have huge reserves of U.S. dollars in their holdings and are significant buyers of U.S. treasury bills and notes.[78]

Foreign companies, entities, and private individuals hold U.S. dollars in foreign deposit accounts called eurodollars (not to be confused with the euro), which are outside the jurisdiction of the Federal Reserve System. Private individuals also hold dollars outside the banking system mostly in the form of US$100 bills, of which 80% of its supply is held overseas.

The United States Department of the Treasury exercises considerable oversight over the SWIFT financial transfers network,[79] and consequently has a huge sway on the global financial transactions systems, with the ability to impose sanctions on foreign entities and individuals.[80]

In the global markets

[edit]The U.S. dollar is predominantly the standard currency unit in which goods are quoted and traded, and with which payments are settled, in the global commodity markets.[81] The U.S. Dollar Index is an important indicator of the dollar's strength or weakness versus a basket of six foreign currencies.

The United States Government is capable of borrowing trillions of dollars from the global capital markets in U.S. dollars issued by the Federal Reserve, which is itself under U.S. government purview, at minimal interest rates, and with virtually zero default risk. In contrast, foreign governments and corporations incapable of raising money in their own local currencies are forced to issue debt denominated in U.S. dollars, along with its consequent higher interest rates and risks of default.[82] The United States's ability to borrow in its own currency without facing a significant balance of payments crisis has been frequently described as its exorbitant privilege.[83]

A frequent topic of debate is whether the strong dollar policy of the United States is indeed in America's own best interests, as well as in the best interest of the international community.[84]

Currencies fixed to the U.S. dollar

[edit]For a more exhaustive discussion of countries using the U.S. dollar as official or customary currency, or using currencies which are pegged to the U.S. dollar, see International use of the U.S. dollar#Dollarization and fixed exchange rates and Currency substitution#US dollar.

Countries using the U.S. dollar as their official currency include:

- In the Americas: Panama, Ecuador, El Salvador, British Virgin Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, and the Caribbean Netherlands.

- The constituent states of the former Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands: Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands.

- Others: Timor-Leste.

Among the countries using the U.S. dollar together with other foreign currencies and their local currency are Cambodia and Zimbabwe.

Currencies pegged to the U.S. dollar include:

- In the Caribbean: the Bahamian dollar, Barbadian dollar, Belize dollar, Bermudian dollar, Cayman Islands dollar, Caribbean guilder, Eastern Caribbean dollar and the Aruban florin.

- The currencies of five oil-producing Arab countries: the Saudi riyal, United Arab Emirates dirham, Omani rial, Qatari riyal and the Bahraini dinar.

- Others: the Hong Kong dollar, Macanese pataca, Jordanian dinar, Lebanese pound.

Value

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: No new data from the past 12 years (ignoring the difficult to read graphs up to 2021 labeled "Inflation of the dollar"), but prices of many foods along have increased 2–4x or more as one example, but pay isn't increasing at all for most people. The actual inflation numbers would be interesting.. (April 2024) |

|

|

|

The 6th paragraph of Section 8 of Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution provides that the U.S. Congress shall have the power to "coin money" and to "regulate the value" of domestic and foreign coins. Congress exercised those powers when it enacted the Coinage Act of 1792. That Act provided for the minting of the first U.S. dollar and it declared that the U.S. dollar shall have "the value of a Spanish milled dollar as the same is now current".[85]

The table above shows the equivalent amount of goods that, in a particular year, could be purchased with $1. The table shows that from 1774 through 2012 the U.S. dollar has lost about 97.0% of its buying power.[86]

The decline in the value of the U.S. dollar corresponds to price inflation, which is a rise in the general level of prices of goods and services in an economy over a period of time.[87] A consumer price index (CPI) is a measure estimating the average price of consumer goods and services purchased by households. The United States Consumer Price Index, published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, is a measure estimating the average price of consumer goods and services in the United States.[88] It reflects inflation as experienced by consumers in their day-to-day living expenses.[89] A graph showing the U.S. CPI relative to 1982–1984 and the annual year-over-year change in CPI is shown at right.

The value of the U.S. dollar declined significantly during wartime, especially during the American Civil War, World War I, and World War II.[90] The Federal Reserve, which was established in 1913, was designed to furnish an "elastic" currency subject to "substantial changes of quantity over short periods", which differed significantly from previous forms of high-powered money such as gold, national banknotes, and silver coins.[91] Over the very long run, the prior gold standard kept prices stable—for instance, the price level and the value of the U.S. dollar in 1914 were not very different from the price level in the 1880s. The Federal Reserve initially succeeded in maintaining the value of the U.S. dollar and price stability, reversing the inflation caused by the First World War and stabilizing the value of the dollar during the 1920s, before presiding over a 30% deflation in U.S. prices in the 1930s.[92]

Under the Bretton Woods system established after World War II, the value of gold was fixed to $35 per ounce, and the value of the U.S. dollar was thus anchored to the value of gold. Rising government spending in the 1960s, however, led to doubts about the ability of the United States to maintain this convertibility, gold stocks dwindled as banks and international investors began to convert dollars to gold, and as a result, the value of the dollar began to decline. Facing an emerging currency crisis and the imminent danger that the United States would no longer be able to redeem dollars for gold, gold convertibility was finally terminated in 1971 by President Nixon, resulting in the "Nixon shock".[93]

The value of the U.S. dollar was therefore no longer anchored to gold, and it fell upon the Federal Reserve to maintain the value of the U.S. currency. The Federal Reserve, however, continued to increase the money supply, resulting in stagflation and a rapidly declining value of the U.S. dollar in the 1970s. This was largely due to the prevailing economic view at the time that inflation and real economic growth were linked (the Phillips curve), and so inflation was regarded as relatively benign.[93] Between 1965 and 1981, the U.S. dollar lost two thirds of its value.[86]

In 1979, President Carter appointed Paul Volcker Chairman of the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve tightened the money supply and inflation was substantially lower in the 1980s, and hence the value of the U.S. dollar stabilized.[93]

Over the thirty-year period from 1981 to 2009, the U.S. dollar lost over half its value.[86] This is because the Federal Reserve has targeted not zero inflation, but a low, stable rate of inflation—between 1987 and 1997, the rate of inflation was approximately 3.5%, and between 1997 and 2007 it was approximately 2%. The so-called "Great Moderation" of economic conditions since the 1970s is credited to monetary policy targeting price stability.[94]

There is an ongoing debate about whether central banks should target zero inflation (which would mean a constant value for the U.S. dollar over time) or low, stable inflation (which would mean a continuously but slowly declining value of the dollar over time, as is the case now). Although some economists are in favor of a zero inflation policy and therefore a constant value for the U.S. dollar,[92] others contend that such a policy limits the ability of the central bank to control interest rates and stimulate the economy when needed.[95]

Pegged currencies

[edit]- Aruban florin (lower value)

- Bahamian dollar (at par)

- Bahraini dinar (higher value)

- Barbadian dollar (lower value)

- Belarusian ruble (alongside Euro and Russian ruble in currency basket)

- Belize dollar (lower value)

- Bermudian dollar (at par)

- Bolivian boliviano (lower value)

- Cambodian riel (lower value)

- Caribbean guilder (lower value)

- Cayman Islands dollar (higher value)

- Costa Rican colón (lower value)

- Cuban peso (lower value)

- Eastern Caribbean dollar (lower value)

- Ecuadorian centavo coins (at par)

- Eritrean nakfa (lower value)

- Guatemalan quetzal (lower value)

- Haitian gourde (lower value)

- Honduran lempira (lower value)

- Hong Kong dollar (narrow band)

- Iraqi dinar (lower value)

- Jordanian dinar (higher value)

- Kuwaiti dinar (higher value)

- Lebanese pound (lower value)

- Nicaraguan córdoba (lower value)

- Nigerian naira (lower value)

- Omani rial (higher value)

- Panamanian balboa (at par)

- Qatari riyal (lower value)

- Saudi riyal (lower value)

- Sierra Leonean leone (lower value)

- Timor-Leste centavo coins (at par)

- Trinidad and Tobago dollar (lower value)

- United Arab Emirates dirham (lower value)

- Yemeni rial (lower value)

Currencies formerly with pegs

[edit](incomplete list)

- Argentine austral (1985–1991: fluctuating peg to USD)[96]

- Argentine peso (1991–2002: 1/USD)[96]

- Chinese yuan (until 2005: 1/USD)[97]

- Indonesian rupiah (until 1997: 1/USD)[98]

- Malaysian ringgit (1998–2005: 3.80/USD)[98]

- Mexican peso (1933–1948: 8.65/USD, 1954–1976: 12.5/USD)[99][100]

- South Korean won (until 1997: 1/USD)[98]

- Thai baht (until 1997: 1/USD)[97]

Obsolete currencies with USD peg

[edit]- Salvadoran colón (lower value)

- Zimbabwean bond coins and bond notes (at par)

Exchange rates

[edit]Historical exchange rates

[edit]| Currency units | 1970[i] | 1980[i] | 1985[i] | 1990[i] | 1993 | 1999 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2018[105] | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro | — | — | — | — | — | 0.9387 | 1.0832 | 0.8033 | 0.6739 | 0.9015 | 0.8504 | 0.9239 |

| Japanese yen | 357.6 | 240.45 | 250.35 | 146.25 | 111.08 | 113.73 | 107.80 | 110.11 | 87.78 | 121.05 | 111.130 | 151.4551 |

| Pound sterling | 8s 4d =0.4167 |

0.4484[ii] | 0.8613[ii] | 0.6207 | 0.6660 | 0.6184 | 0.6598 | 0.5493 | 0.4548 | 0.6544 | 0.7454 | 0.7827 |

| Swiss franc | 4.12 | 1.68 | 2.46[106] | 1.39 | 1.48 | 1.50 | 1.69 | 1.15 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.8808 |

| Canadian dollar[107] | 1.081 | 1.168 | 1.321 | 1.1605 | 1.2902 | 1.4858 | 1.4855 | 1.2115 | 1.0298 | 1.2789 | 1.2842 | 1.3699 |

| Mexican peso[108] | 0.0195[iii] | 2.80[iii] | 2.67[iii] | 2.50[iii] | 3.1237 | 9.553 | 9.459 | 10.894 | 12.623 | 15.837 | 19.911 | 18.3062 |

| Soviet[109] / Russian ruble[110] | 0.9000 | 0.6395 | 0.9200 | 0.6072 | 1.0037 | 24.6489 | 28.1287 | 28.1910 | 30.3679 | 61.3400 | 62.9502 | 92.6567 |

| Chinese Renminbi[111] | 2.46 | 1.7050 | 2.9366 | 4.7832 | 5.7620 | 8.2783 | 8.2784 | 8.1936 | 6.7696 | 6.2840 | 6.383 | 7.1957 |

| Pakistani rupee | 4.761 | 9.9 | 15.9284 | 21.707 | 28.107 | 51.9 | 51.9 | 59.7 | 85.75 | 104.763 | 139.850 | 278.390 |

| Singapore dollar | — | — | 2.179 | 1.903 | 1.6158 | 1.6951 | 1.7361 | 1.6639 | 1.24586 | 1.3748 | 1.343 | 1.3363 |

| South Korean won | 310.556 | 607.717 | 870.020 | 707.766 | 802.538 | 1189.439 | 1130.362 | 1024.328 | 1156.460 | 1130.953 | 1100.163 | 1363.438 |

(on the first two - the amount of dollars per one euro and pound, on the third - the amount of yens per one dollar)

(the amount of Canadian dollars, pesos and renminbi per one dollar)

Current exchange rates

[edit]| Current USD exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY CAD TWD KRW |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY CAD TWD KRW |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY CAD TWD KRW |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY CAD TWD KRW |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Also abbreviated US$ to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck

- ^ Silver bullion can be converted in unlimited quantities of Trade dollars of 420 grains, but these were meant for export and had legal tender limits in the US. See Trade dollar (United States coin).

- ^ Obverse

- ^ Reverse

- ^ See Federal Reserve Note § Lawsuit over U.S. banknote design for details and references.

- ^ a b c d Mexican peso values prior to 1993 revaluation

- ^ a b 1970–1992 Archived October 23, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. 1980 derived from AUD–USD=1.1055 and AUD–GBP=0.4957 at end of Dec 1979: 0.4957/1.1055=0.448394392; 1985 derived from AUD–USD=0.8278 and AUD–GBP=0.7130 at end of Dec 1984: 0.7130/0.8278=0.861319159.

- ^ a b c d Value at the start of the year

References

[edit]- ^ "Coinage Act of 1792" (PDF). United States Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2004. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- ^ "A Constitutional Dollar". Mises.org. March 10, 2010.

- ^ "Nixon Ends Convertibility of US Dollars to Gold and Announces Wage/Price Controls". Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ "The Implementation of Monetary Policy – The Federal Reserve in the International Sphere" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 27, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ Cohen, Benjamin J. 2006. The Future of Money, Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11666-0.

- ^ Agar, Charles. 2006. Vietnam, (Frommer's). ISBN 0-471-79816-9. p. 17: "the dollar is the de facto currency in Cambodia."

- ^ "How much U.S. currency is in circulation?". Federal Reserve. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ "Federal Reserve Balance Sheet: Factors Affecting Reserve Balances - H.4.1". January 2, 2025. Archived from the original on January 11, 2025.

- ^ U.S. Constitution, Article 1, Section 8. para. 5 Archived November 18, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Denominations, specifications, and design of coins. 31 U.S.C. § 5112.

- ^ a b Denominations, specifications, and design of coins. 31 U.S.C. § 5112.

- ^ U.S. Constitution, Article 1, Section 9. para. 7 Archived November 18, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Reports. 31 U.S.C. § 331.

- ^ "Financial Report of the United States Government" (PDF). Department of the Treasury. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 13, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ U.S. Congress. 1792. Coinage Act of 1792. 2nd Congress, 1st Session. Sec. 9, ch. 16. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- ^ U.S. Congress. 1792. Coinage Act of 1792. 2nd Congress, 1st Session. Sec. 9, ch. 16. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Fitzpatrick, John C., ed. (1934). "Tuesday, August 8, 1786". Journals of the Continental Congress 1774–1789. XXXI: 1786: 503–505. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ Peters, Richard, ed. (1845). "Second Congress. Sess. I. Ch. 16". The Public Statutes at Large of the United States of America, Etc. Etc. 1: 246–251. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ Langland, Connie (May 27, 2015). "What is a millage rate and how does it affect school funding?". WHYY. PBS and NPR. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "Mills Currency". Past & Present. Stamp and Coin Place Blog. September 26, 2018. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "How much is "two bits" and where did the phrase". Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ "Decimal Trading Definition and History". Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ Mehl, B. Max. "United States $50.00 Gold Pieces, 1877", in Star Rare Coins Encyclopedia and Premium Catalogue (20th edition, 1921)

- ^ a b "Ask US." National Geographic. June 2002. p. 1.

- ^ There is no solid reference on the desirability of liondollars in North America and on 1:1 parity with heavier dollars. A dollar worth $0.80 Spanish is not cheap if priced at $0.50 http://coins.lakdiva.org/netherlands/1644_wes_lion_daalder_ag.html Archived February 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine https://coins.nd.edu/ColCoin/ColCoinIntros/Lion-Dollar.intro.html Archived July 10, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Buck". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ "Paper Money Glossary". Littleton Coin Company. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ Scutt, David (June 3, 2019). "The Australian dollar is grinding higher as expectations for rate cuts from the US Federal Reserve build". Business Insider. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ Tappe, Anneken (August 9, 2018). "New Zealand dollar leads G-10 losers as greenback gains strength". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ "South Africa's rand firms against greenback, stocks rise". Reuters. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ "Why rupee is once again under pressure". Business Today. April 22, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ Cajori, Florian ([1929]1993). A History of Mathematical Notations (Vol. 2). New York: Dover, 15–29. ISBN 0-486-67766-4

- ^ Aiton, Arthur S.; Wheeler, Benjamin W. (1931). "The First American Mint". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 11 (2). p. 198 and note 2 on p. 198. doi:10.1215/00182168-11.2.198. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2506275.

- ^ Nussbaum, Arthur (1957). A History of the Dollar. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 56.

The dollar sign, $, is connected with the peso, contrary to popular belief, which considers it to be an abbreviation of 'U.S.' The two parallel lines represented one of the many abbreviations of 'P,' and the 'S' indicated the plural. The abbreviation '$.' was also used for the peso, and is still used in Argentina.

- ^ "U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing – FAQs". www.bep.gov. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ "From the Spanish dollar to the US dollar". Iberdrola. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ Rand, Ayn. [1957] 1992. Atlas Shrugged. Signet. p. 628.

- ^ James, James Alton (1970) [1937]. Oliver Pollock: The Life and Times of an Unknown Patriot. Freeport: Books for Libraries Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-8369-5527-9.

- ^ Mint, U.S. (April 6, 2017). "Coinage Act of 1792". U.S. treasury. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ Mason, Seth (January 7, 2013). "The Definitive Inflation Chart". Ecominoes. Archived from the original on October 19, 2018..

- ^ Sumner, W. G. (1898). "The Spanish Dollar and the Colonial Shilling". The American Historical Review. 3 (4): 607–619. doi:10.2307/1834139. JSTOR 1834139. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ "United States Dollar". OANDA. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ "Engraving and printing currency and security documents:Article b". Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on December 20, 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ Matt Soniak (July 22, 2011). "On the Money: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Coin Portraits". Mental Floss. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ Newman, Eric P. (1990). The Early Paper Money of America (3 ed.). Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 17. ISBN 0-87341-120-X.

- ^ Wright, Robert E. (2008). One Nation Under Debt: Hamilton, Jefferson, and the History of What We Owe. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-0-07-154393-4.

- ^ Anderson, Gordon T. April 25, 2005. "Congress tries again for a dollar coin Archived March 21, 2022, at the Wayback Machine." CNN Money.

- ^ Christian Zappone (July 18, 2006). "Kill-the-penny bill introduced". CNN Money. Archived from the original on July 28, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ Weinberg, Ali (February 19, 2013). "Penny pinching: Can Obama manage elimination of one-cent coin?". NBC News. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ Gibbs, William T. (June 29, 2023). "Series 2021 dollar notes now being found in circulation". Coin World. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ Meyersohn, Nathaniel (September 20, 2022). "Why it's time to start paying with $2 bills". CNN. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ^ "5 Dollars (Federal Reserve Note; colored) - United States". Numista. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ "$100 Note | U.S. Currency Education Program". Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ "Paragraph 2 of Section 8 of Article 1 of the United States Constitution". Topics.law.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ "Section 411 of Title 12 of the United States Code". Law.cornell.edu. June 22, 2010. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ "Section 5103 of Title 31 of the United States Code". Law.cornell.edu. August 6, 2010. Archived from the original on October 22, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ "Section 5115 of Title 31 of the United States Code". Law.cornell.edu. August 6, 2010. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ "Treasury Department Appropriation Bill for 1929: Hearing Before the Subcommittee of House Committee on Appropriations... Seventieth Congress, First Session". 1928.

- ^ Schwarz, John; Lindquist, Scott (September 21, 2009). Standard Guide to Small-Size U.S. Paper Money – 1928-Date. Penguin. ISBN 9781440225789.

- ^ Orzano, Michele (February 25, 2015). "What is a horse blanket note?". Coin World. Archived from the original on November 29, 2021.

- ^ "Ecuador". CIA World Factbook. October 18, 2010. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

The dollar is legal tender

- ^ "El Salvador". CIA World Factbook. October 21, 2010. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

The US dollar became El Salvador's currency in 2001

- ^ "Currency". Central Bank of Liberia. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "Central Bank of Timor-Leste". Archived from the original on May 1, 2019. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

The official currency of Timor-Leste is the United States dollar, which is legal tender for all payments made in cash.

- ^ Nay Im, Tal; Dabadie, Michel (March 31, 2007). "Dollarization in Cambodia" (PDF). National Bank of Cambodia. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ Nagumo, Jada (August 4, 2021). "Cambodia aims to wean off US dollar dependence with digital currency". Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

Cambodia runs a dual-currency system, with the U.S. dollar widely circulating in its economy. The country's dollarization began in the 1980s and 90s, following years of civil war and unrest.

- ^ Rivera, Juan Carlos (November 23, 2023). "Roatán prefiere cobrar en dólares o lempiras; no bitcóin" [Roatán prefers to charge in dollars or lempiras; not bitcoin]. laprensa.hn (in Spanish). La Prensa. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ "Lebanon leans on US dollar to cope as currency, economy tank". Associated Press. March 6, 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2024.

- ^ Zerpa, Fabiola (November 5, 2019). "Venezuela Is Now More Than 50% Dollarized, Study Finds". Bloomberg. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ^ "Maduro says 'thank God' for dollarization in Venezuela". Reuters. November 17, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ "Federal Reserve Board – Purposes & Functions". Archived from the original on March 26, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ "Conducting Monetary Policy" (PDF). United States Federal Reserve. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ "St. Louis Adjusted Monetary Base". Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. February 15, 1984. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ "Fact Sheets: Currency & Coins". United States Department of the Treasury. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ "'The Silver Way' Explains How the Old Mexican Dollar Changed the World". April 30, 2017. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ Eichengreen, Barry; Flandreau, Marc (2009). "The rise and fall of the dollar (or when did the dollar replace sterling as the leading reserve currency?)". European Review of Economic History. 13 (3): 377–411. doi:10.1017/S1361491609990153. ISSN 1474-0044. S2CID 154773110. Archived from the original on January 7, 2023. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ "How a 1944 Agreement Created a New World Order". Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ "MAJOR FOREIGN HOLDERS OF TREASURY SECURITIES". US Treasury. March 15, 2023. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "SWIFT oversight". Archived from the original on June 16, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ "Sanctions Programs and Country Information | U.S. Department of the Treasury". Archived from the original on June 16, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ "Impact of the Dollar on Commodity Prices". Archived from the original on March 1, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ "Dollar Bond". Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ Bernanke, Ben S. (January 7, 2016). "The dollar's international role: An "exorbitant privilege"?". Archived from the original on June 8, 2021.

- ^ Mohsin, Saleha (January 21, 2021). "The Strong Dollar". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on August 22, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ "Section 9 of the Coinage Act of 1792". American Memory - Library of Congress. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Measuring Worth – Purchasing Power of Money in the United States from 1774 to 2010". Archived from the original on June 16, 2023. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- ^ Olivier Blanchard (2000). Macroeconomics (2nd ed.), Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-013306-X

- ^ "Consumer Price Index Frequently Asked Questions". Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- ^ "Consumer Price Index Frequently Asked Questions". Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ Milton Friedman, Anna Jacobson Schwartz (November 21, 1971). A monetary history of the United States, 1867–1960. Princeton University Press. p. 546. ISBN 978-0691003542.

- ^ Friedman 189–190

- ^ a b Broaddus Jr., J. Alfred (September 1, 1993). "Central Banking—Then and Now". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Archived from the original on October 26, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c Emery, Kenneth M. "Controlling Inflation: A Historical Perspective" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2010. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ^ Ferguson, Roger W. Jr. (November 3, 2005). "Monetary Credibility, Inflation, and Economic Growth". FRB. Archived from the original on August 15, 2010. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ^ "What are the goals of U.S. monetary policy?". Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. February 6, 2004. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ a b Rafael M. Di Tella and Ingrid Vogel (December 2001). "Argentina's Convertibility Plan". Harvard Business School. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ a b "Pegged and Crawling Pegged Rate Systems". UNCG. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Exchange Rate Systems". University of Minnesota. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ Nora Lustig (June 1, 1995). "The Mexican Peso Crisis: The Foreseeable and the Surprise". Brookings Institution. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ "What's Behind the Volatility of Mexico's Peso?". Knowledge at Wharton. March 9, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Federal Reserve: Last 4 years Archived October 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, 2009–2012 Archived October 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, 2005–2008 Archived October 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, 2001–2004 Archived October 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, 1997–2000 Archived October 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, 1993–1996 Archived October 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine; Reserve Bank of Australia: 1970–present Archived October 23, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "2004–present". Archived from the original on July 23, 2014. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ "FRB: Foreign Exchange Rates – G.5A; Release Dates". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Archived from the original on August 3, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Exchange rates". OECD.

- ^ "Historical Exchange Rates Currency Converter". TransferMate.com. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ "Exchange Rates Between the United States Dollar and the Swiss Franc Archived March 30, 2019, at the Wayback Machine." Measuring Worth. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ 1977–1991

- ^ "International Economics - Historial Exchange Rate Regime of Asian Countries". intl.econ.cuhk.edu.hk.

- ^ Soviet ruble until 1991 | "Archive". Central Bank of Russia. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ Russian ruble 1992 onwards | USD exchange rates in RUB Archived 11 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Bank of Russia

- ^ 1974–1991, 1993–1995

Further reading

[edit]- Prasad, Eswar S. (2014). The Dollar Trap: How the U.S. Dollar Tightened Its Grip on Global Finance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16112-9.

External links

[edit]- U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing Archived May 30, 1997, at the Wayback Machine

- U.S. Currency and Coin Outstanding and in Circulation

- American Currency Exhibit at the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank Archived June 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- Relative values of the U.S. dollar, from 1774 to present

- Historical Currency Converter

- Summary of BEP Production Statistics

- The U.S. Currency Education Program

Images of U.S. currency and coins

[edit]United States dollar

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Basic Features

Legal Basis and Characteristics

The authority for the United States dollar as the nation's currency stems from Article I, Section 8, Clause 5 of the U.S. Constitution, which empowers Congress "To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures."[10] This clause vests exclusive federal control over monetary standards, prohibiting states from coining money or emitting bills of credit under Article I, Section 10. The Coinage Act of April 2, 1792, operationalized this constitutional power by creating the United States Mint in Philadelphia and defining the dollar as the principal unit of account, equivalent to 371.25 grains of pure silver or 24.75 grains of pure gold, with a bimetallic standard fixing the gold-silver ratio at approximately 15:1.[11] The Act further mandated a decimal-based subdivision, expressing values in dollars (units), dimes (tenths), and cents (hundredths), thereby establishing the enduring structure of U.S. currency denominations.[12] As legal tender, United States coins and currency, including Federal Reserve notes, must be accepted for all public charges, taxes, duties, and debts, public and private, per 31 U.S.C. § 5103, enacted to affirm their compulsory acceptance without regard to design or issuance date.[13] The dollar functions as fiat money, deriving value from governmental declaration and public trust rather than redeemability in a fixed commodity such as silver or gold; it is not pegged to silver or other commodities, with silver certificate redemption for silver having ended in 1968. This status was solidified after the suspension of gold convertibility for private holders in 1933 and internationally in 1971.[14] Coins are minted by the U.S. Mint under the Department of the Treasury, while paper currency is issued as Federal Reserve notes, liabilities of the Federal Reserve Banks backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.[11] This framework ensures uniformity, with counterfeiting punishable as a federal crime under 18 U.S.C. § 471 et seq., reflecting Congress's regulatory oversight.[10]Denominations and Units

The United States dollar is subdivided into 100 cents, with the cent (symbol ¢) serving as the primary subunit for smaller transactions.[15] Coins are issued by the United States Mint in denominations of 1 cent (penny), 5 cents (nickel), 10 cents (dime), and 25 cents (quarter dollar), which constitute the primary circulating coins used in everyday commerce.[16] Additionally, 50-cent (half dollar) and 1-dollar coins are minted annually, primarily for collectors and institutional demand rather than widespread circulation, with production figures reflecting limited public use.[16] Federal Reserve Notes, the predominant form of paper currency, are printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in seven denominations: $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100.[17] The $100 note is the highest denomination currently issued for circulation, as larger bills ($500, $1,000, $5,000, and $10,000) ceased production after 1945 and, while remaining legal tender, are no longer manufactured or commonly encountered.[18] [15]| Coin Denomination | Common Name | Primary Composition (as of 2025) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 cent | Penny | Copper-plated zinc |

| 5 cents | Nickel | Cupronickel clad copper |

| 10 cents | Dime | Cupronickel clad copper |

| 25 cents | Quarter | Cupronickel clad copper |

| 50 cents | Half dollar | Cupronickel clad copper |

| $1 | Dollar | Manganese-brass clad copper |

Symbols, Etymology, and Nicknames