Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cholescintigraphy

View on Wikipedia| Cholescintigraphy | |

|---|---|

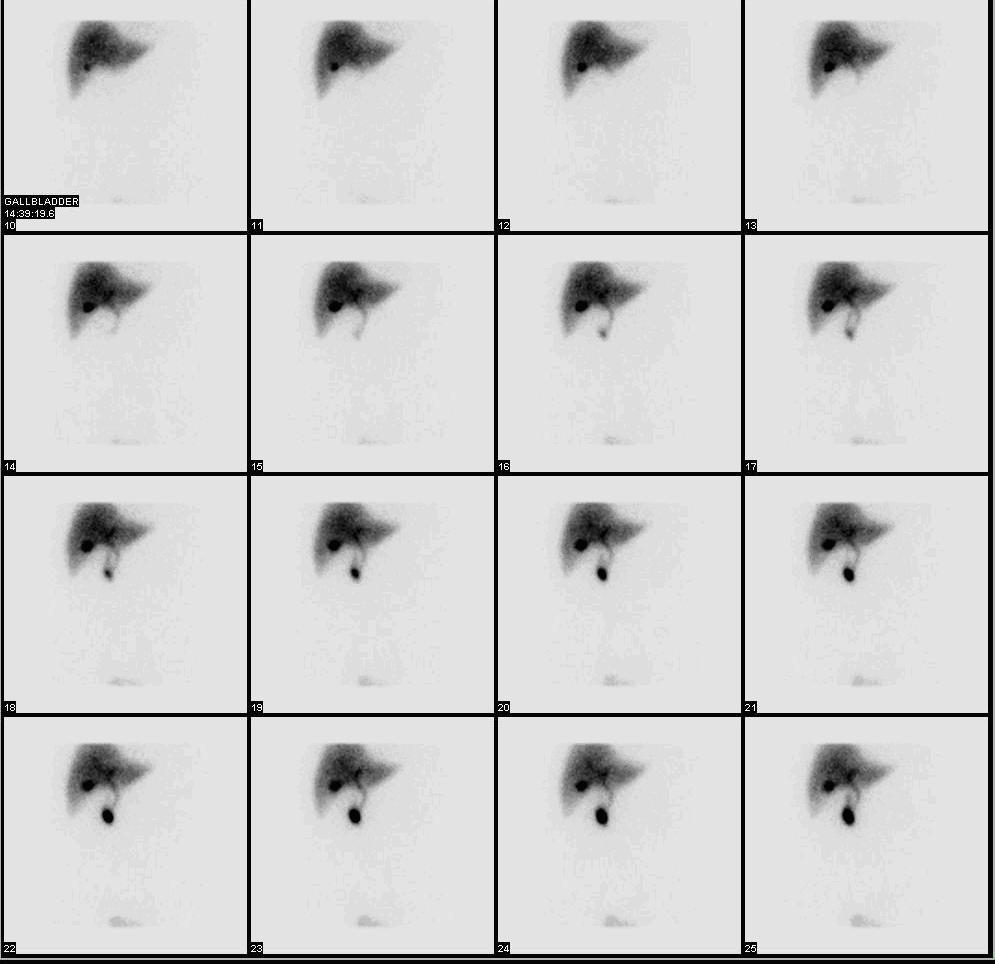

Normal hepatobiliary scan (HIDA scan). The nuclear medicine hepatobiliary scan is clinically useful in the detection of the gallbladder disease. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 92.02 |

| OPS-301 code | 3-707.6 |

Cholescintigraphy or hepatobiliary scintigraphy is scintigraphy of the hepatobiliary tract, including the gallbladder and bile ducts. The image produced by this type of medical imaging, called a cholescintigram, is also known by other names depending on which radiotracer is used, such as HIDA scan, PIPIDA scan, DISIDA scan, or BrIDA scan.[1][2] Cholescintigraphic scanning is a nuclear medicine procedure to evaluate the health and function of the gallbladder and biliary system. A radioactive tracer is injected through any accessible vein and then allowed to circulate to the liver, where it is excreted into the bile ducts and stored by the gallbladder[3] until released into the duodenum.

Use of cholescintigraphic scans as a first-line form of imaging varies depending on indication. For example for cholecystitis, cheaper and less invasive ultrasound imaging may be preferred,[4] while for bile reflux cholescintigraphy may be the first choice.[5]

Etymology and pronunciation

[edit]The word cholescintigraphy (/ˌkoʊliˌsɪnˈtɪɡrəfi/) uses combining forms of chole- + scinti(llation) + -graphy, most literally "bile + flash + recording".

Medical use

[edit]In the absence of gallbladder disease, the gallbladder is visualized within 1 hour of the injection of the radioactive tracer.[citation needed]

If the gallbladder is not visualized within 4 hours after the injection, this indicates either cholecystitis or cystic duct obstruction, such as by cholelithiasis (gallstone formation).[6]

Cholecystitis

[edit]The investigation is usually conducted after an ultrasonographic examination of the abdominal right upper quadrant for a patient presenting with abdominal pain. If the noninvasive ultrasound examination fails to demonstrate gallstones, or other obstruction to the gallbladder or biliary tree, in an attempt to establish a cause of right upper quadrant pain, a cholescintigraphic scan can be performed as a more sensitive and specific test.[citation needed]

Cholescintigraphy for acute cholecystitis has sensitivity of 97%, specificity of 94%.[7] Several investigators have found the sensitivity being consistently higher than 90% though specificity has varied from 73–99%, yet compared to ultrasonography, cholescintigraphy has proven to be superior.[8] The scan is also important to differentiate between neonatal hepatitis and biliary atresia, because an early surgical intervention in form of Kasai portoenterostomy or hepatoportoenterostomy can save the life of the baby as the chance of a successful operation after 3 months seriously decreases.[9]

Biliary dyskinesia

[edit]Cholescintigraphy is also used in diagnosis of the biliary dyskinesia.

Radiotracers

[edit]Most radiotracers for cholescintigraphy are metal complexes of iminodiacetic acid (IDA) with a radionuclide, usually technetium-99m. This metastable isotope has a half-life of 6 hours, so batches of radiotracer must be prepared as needed using a moly cow. A widely recognized trade name for the preparation kits is TechneScan. These radiopharmaceuticals include the following:[10][11]

| Nonproprietary drug name (USP format) | Common chemical name | Acronym | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| technetium Tc 99m lidofenin | hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid;[12] dimethyl-iminodiacetic acid[10] | HIDA | An early and widely used tracer; not used as much anymore, as others have progressively replaced it,[13][6] but the term "HIDA scan" is sometimes used even when another tracer was involved, being treated as a catch-all synonym. |

| technetium Tc 99m iprofenin | paraisopropyl-iminodiacetic acid[10] | PIPIDA | |

| technetium Tc 99m disofenin | diisopropyl-iminodiacetic acid[10] | DISIDA | |

| technetium Tc 99m mebrofenin | trimethylbromo-iminodiaceticacid[12] | BrIDA | |

| diethyl-iminodiacetic acid[10] | EIDA | Seems to have been a laboratory tracer but never widely used clinically | |

| parabutyl-iminodiacetic acid[10] | PBIDA | Seems to have been a laboratory tracer but never widely used clinically | |

| BIDA[14] | Seems to have been a laboratory tracer but never widely used clinically | ||

| DIDA[14] | Seems to have been a laboratory tracer but never widely used clinically |

References

[edit]- ^ Lambie, H.; Cook, A.M.; Scarsbrook, A.F.; Lodge, J.P.A.; Robinson, P.J.; Chowdhury, F.U. (November 2011). "Tc99m- hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scintigraphy in clinical practice". Clinical Radiology. 66 (11): 1094–1105. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2011.07.045. PMID 21861996.

- ^ Kim, Chun K; Joo, Junghyun; Lee, Seokmo (2015). "Digestive System 2: Liver and Biliary Tract". In Elgazzar, Abedlhamid H (ed.). The pathophysiologic basis of nuclear medicine (3rd ed.). Cham: Springer. p. 561. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-06112-2. ISBN 9783319061115.

- ^ Michael, Picco. "HIDA scan (cholescintigraphy): Why is it performed?". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ Kelly, Aine; Cronin, Paul; Puig, Stefan; Applegate, Kimberly E. (2018). Evidence-Based Emergency Imaging: Optimizing Diagnostic Imaging of Patients in the Emergency Care Setting. Springer. p. 313. ISBN 978-3-319-67066-9.

- ^ Eldredge, Thomas A.; Myers, Jennifer C.; Kiroff, George K.; Shenfine, Jonathan (11 December 2017). "Detecting Bile Reflux—the Enigma of Bariatric Surgery". Obesity Surgery. 28 (2): 559–566. doi:10.1007/s11695-017-3026-6. PMID 29230622. S2CID 6118821.

- ^ a b Tulchinsky, M.; Ciak, B. W.; Delbeke, D.; Hilson, A.; Holes-Lewis, K. A.; Stabin, M. G.; Ziessman, H. A. (15 November 2010). "SNM Practice Guideline for Hepatobiliary Scintigraphy 4.0". Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology. 38 (4): 210–218. doi:10.2967/jnmt.110.082289. PMID 21078782.

- ^ Shea JA, Berlin JA, Escarce JJ, Clarke JR, Kinosian BP, Cabana MD, et al. (1994). "Revised estimates of diagnostic test sensitivity and specificity in suspected biliary tract disease". Arch Intern Med. 154 (22): 2573–81. doi:10.1001/archinte.154.22.2573. PMID 7979854.

- ^ L. Santiago Medina; C. Craig Blackmore; Kimberly Applegate (29 April 2011). Evidence-Based Imaging: Improving the Quality of Imaging in Patient Care. Springer. p. 530. ISBN 978-1-4419-7776-2. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ Jorge A. Soto; Brian C. Lucey (27 April 2009). Emergency Radiology: The Requisites. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-323-05407-2. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Bobba, VV; et al. (1983), "Comparison of biokinetics and biliary imaging parameters of four Tc-99m iminodiacetic acid derivatives in normal subjects", Clin Nucl Med, 8 (2): 70–75, doi:10.1097/00003072-198302000-00008, PMID 6825355, S2CID 12260768.

- ^ Brown, PH; et al. (1982), "Radiation-dose calculation for five Tc-99m IDA hepatobiliary agents", J Nucl Med, 23 (11): 1025–1030, PMID 6897074.

- ^ a b Elsevier, Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, Elsevier.

- ^ Krishnamurthy, Gerbail T.; Krishnamurthy, Shakuntala (31 July 2009). Nuclear Hepatology: A Textbook of Hepatobiliary Diseases. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-00647-0.

- ^ a b Ziessman, HA; et al. (2014), "Hepatobiliary scintigraphy in 2014", J Nucl Med, 55 (6): 967–975, doi:10.2967/jnumed.113.131490, PMID 24744445.