Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gastrectomy

View on WikipediaYou can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Japanese. (July 2013) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Gastrectomy | |

|---|---|

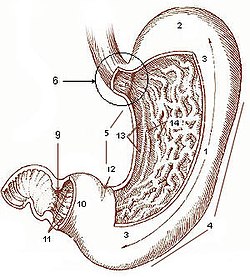

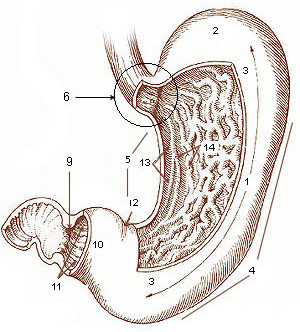

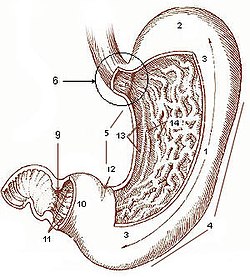

Diagram of the stomach, showing the different regions. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 43.5-43.9 |

| MeSH | D005743 |

| MedlinePlus | 002945 |

A gastrectomy is a partial or total surgical removal of the stomach.

Indications

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

Gastrectomies are performed to treat stomach cancer and perforations of the stomach wall.

For severe duodenal ulcers, it may be necessary to remove the lower portion of the stomach and the upper portion of the small intestine. If there is a sufficient portion of the upper duodenum remaining, a Billroth I procedure is performed, where the remaining portion of the stomach is reattached to the duodenum before the common bile duct. If the stomach cannot be reattached to the duodenum, a Billroth II is performed, wherein the remaining portion of the duodenum is sealed off, a hole is cut into the next section of the small intestine (called the jejunum), and the stomach is reattached at this hole. As the pylorus is used to grind food and slowly release the food into the small intestine, removal of the pylorus can cause food to move into the small intestine faster than normal, leading to gastric dumping syndrome.

Polya's operation

[edit]Also known as the Reichel–Polya operation, this is a type of posterior gastroenterostomy which is a modification of the Billroth II operation[1] developed by Eugen Pólya and Friedrich Paul Reichel. It involves a resection of 2/3 of the stomach with blind closure of the duodenal stump, and a retrocolic gastrojejunostomy.

Post-operative effects

[edit]The most obvious effect of the removal of the stomach is the loss of a storage place for food while it is being digested. Since only a small amount of food can be allowed into the small intestine at a time, the patient will have to eat small amounts of food regularly in order to prevent gastric dumping syndrome.

Another major effect is the loss of the intrinsic-factor-secreting parietal cells in the stomach lining. Intrinsic factor is essential for the uptake of vitamin B12 in the terminal ileum, and without it the patient will develop a vitamin B12 deficiency. This can lead to a type of anaemia known as megaloblastic anaemia (can also be caused by folate deficiency, or autoimmune disease where it is specifically known as pernicious anaemia) which severely reduces red-blood cell synthesis (known as erythropoiesis, as well as other haematological cell lineages if severe enough but the red cell is the first to be affected). This can be treated by giving the patient direct injections of vitamin B12. Iron-deficiency anemia can occur as the stomach normally converts iron into its absorbable form.[2]

Another side effect is the loss of ghrelin production, which has been shown to be compensated after a while.[3] Lastly, this procedure is post-operatively associated with decreased bone density and higher incidence of bone fractures. This may be due to the importance of gastric acid in calcium absorption.[4]

Post-operatively, up to 70% of patients undergoing total gastrectomy develop complications such as dumping syndrome and reflux esophagitis.[5] A meta-analysis of 25 studies found that construction of a "pouch", which serves as a "stomach substitute", reduced the incidence of dumping syndrome and reflux esophagitis by 73% and 63% respectively, and led to improvements in quality-of-life, nutritional outcomes, and body mass index.[5]

After Bilroth II surgery, a small amount of residual gastric tissue may remain in the duodenum. The alkaline environment causes the retained gastric tissue to produce acid, which may result in ulcers in a rare complication known as retained antrum syndrome.

All patients lose weight after gastrectomy, although the extent of weight loss is dependent on the extent of surgery (total gastrectomy vs partial gastrectomy) and the pre-operative BMI. Maximum weight loss occurs by 12 months and many patients regain weight afterwards.[6]

History

[edit]The first successful gastrectomy was performed by Theodor Billroth in 1881 for cancer of the stomach.

Historically, gastrectomies were used to treat peptic ulcers.[7] These are now usually treated with antibiotics, as it was recognized that they are usually due to Helicobacter pylori infection or chemical imbalances in the gastric juices.

In the past a gastrectomy for peptic ulcer disease was often accompanied by a vagotomy, to reduce acid production. This problem is now managed with proton pump inhibitors.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lahey Clinic (1941). Surgical Practice of the Lahey Clinic, Boston, Massachusetts. W.B. Saunders company. p. 217. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "After Stomach Cancer Surgery - Complications : Diet". Archived from the original on 2017-10-09. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

- ^ Masayasu Kojima; Kenji Kangawa (2005). "Ghrelin: Structure and Function" (PDF). Physiol Rev. 85 (2): 495–522. doi:10.1152/physrev.00012.2004. PMID 15788704. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-25. Retrieved 2016-12-25.

- ^ Kopic, Sascha; Geibel, John P. (January 2013). "Gastric acid, calcium absorption, and their impact on bone health". Physiological Reviews. 93 (1): 189–268. doi:10.1152/physrev.00015.2012. ISSN 1522-1210. PMID 23303909.

- ^ a b Syn, Nicholas L.; Wee, Ian; Shabbir, Asim; Kim, Guowei; So, Jimmy Bok-Yan (October 2018). "Pouch Versus No Pouch Following Total gastrectomy". Annals of Surgery (6): 1041–1053. doi:10.1097/sla.0000000000003082. ISSN 0003-4932. PMID 30571657. S2CID 58584460.

- ^ Davis, Jeremy L.; Selby, Luke V.; Chou, Joanne F.; Schattner, Mark; Ilson, David H.; Capanu, Marinela; Brennan, Murray F.; Coit, Daniel G.; Strong, Vivian E. (May 2016). "Patterns and Predictors of Weight Loss After Gastrectomy for Cancer". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 23 (5): 1639–1645. doi:10.1245/s10434-015-5065-3. ISSN 1068-9265. PMC 4862874. PMID 26732274.

- ^ E. Pólya:Zur Stumpfversorgung nach Magenresektion. Zentralblatt für Chirurgie, Leipzig, 1911, 38: 892-894.