Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Paracentesis

View on Wikipedia| Paracentesis | |

|---|---|

| |

| ICD-10-PCS | Illustration depicting Paracentesis |

| ICD-9-CM | 54.91 |

| MeSH | D019152 |

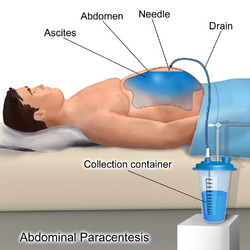

Paracentesis (from Greek κεντάω, "to pierce") is a form of body fluid sampling procedure, generally referring to peritoneocentesis (also called laparocentesis or abdominal paracentesis) in which the peritoneal cavity is punctured by a needle to sample peritoneal fluid.[1][2]

The procedure is used to remove fluid from the peritoneal cavity, particularly if this cannot be achieved with medication. The most common indication is ascites that has developed in people with cirrhosis.

Indications

[edit]

It is used for a number of reasons:[3]

- to relieve abdominal pressure from ascites

- to diagnose spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and other infections (e.g. abdominal TB)

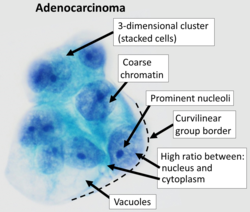

- to diagnose metastatic cancer

- to diagnose blood in peritoneal space in trauma

Paracentesis for ascites

[edit]The procedure is often performed in a doctor's office or an outpatient clinic. In an expert's hands, it is usually very safe,[4] although there is a small risk of infection, excessive bleeding or perforating a loop of bowel. These last two risks can be minimized greatly with the use of ultrasound guidance.[4][5]

Ultrasound guidance

[edit]

The use of ultrasound has become the standard of care when preparing a patient for paracentesis. Confirmation of an ascitic effusion reduces the risks associated with a dry or blind tap of the abdomen. Anatomic landmarks, such as the midline linea alba approach, were traditionally used as reference points for needle insertion. Phased array or curvilinear ultrasound transducers are typically used in the hospital and outpatient setting to identify ascites in the abdominal cavity. Fluid within the abdominal cavity appears hypoechoic or anechoic (black) on ultrasound. Morison's pouch (hepatorenal recess) is a common starting location in concordance with ultrasound FAST (focused assessment with sonography for trauma) exam. Fluid collection can occur in a number of different locations and may be difficult to find, especially if the patient only exhibits a small volume of ascites. Measurement of the amount of fluid within the abdominal cavity is not necessary or very successful. Identification of sufficient fluid within the abdominal cavity for fluid analysis or to achieve a therapeutic benefit is all that is required to proceed to paracentesis. Ultrasound guidance of the paracentesis can also be used as an additional safety measure to ensure the needle stays within the ascitic fluid and avoidance of important vessels within the abdominal cavity.[5]

Procedure overview

[edit]The patient is requested to urinate before the procedure; alternately, a Foley catheter is used to empty the bladder. The patient is positioned in the bed with the head elevated at 45–60 degrees to allow fluid to accumulate in lower abdomen. After cleaning the side of the abdomen with an antiseptic solution, the physician numbs a small area of skin and inserts a large-bore needle with a plastic sheath 2 to 5 cm (1 to 2 in) in length to reach the peritoneal (ascitic) fluid. The needle is removed, leaving the plastic sheath to allow drainage of the fluid. The fluid is drained by gravity, a syringe, or by connection to a vacuum bottle. Several litres of fluid may be drained during the procedure; however, if more than two litres are to be drained, it will usually be done over the course of several treatments.[6] After the desired level of drainage is complete, the plastic sheath is removed and the puncture site bandaged.[6] The plastic sheath can be left in place with a flow control valve and protective dressing if further treatments are expected to be necessary.[6]

If fluid drainage in cirrhotic ascites is more than 5 litres, patients may receive intravenous serum albumin (25% albumin, 8 g/L) to prevent hypotension (low blood pressure).[7] There has been debate as to whether albumin administration confers benefit, but a recent 2016 meta-analysis concluded that it can reduce mortality after large-volume paracentesis significantly.[8] However, for every end-point investigated, while albumin was favorable as compared to other agents (e.g., plasma expanders, vasoconstrictors), these were not statistically significant and the meta-analysis was limited by the quality of the studies—two of which that were in fact unsuitable—included in it.[8]

The procedure generally is not painful and does not require sedation. The patient is usually discharged within several hours following post-procedure observation provided that blood pressure is otherwise normal and the patient experiences no dizziness.[1][9][10]

Complications

[edit]Paracentesis is known to be a safe procedure when ascitic fluid is readily visible, so complications are typically rare. Possible complications following or during the procedure involve infection, bleeding, the leakage ascitic of fluid, or bowel perforation.[7][5] Of these, the most concerning in the immediate setting is bleeding within the peritoneal cavity.[11]

The z-tracking technique has held particular importance in performing paracentesis. A z-track is a technique that allows for decreased ascitic fluid leak following the paracentesis by displacing the needle tracks with respect to the epidermis and the peritoneum.[6]

Fluid analysis

[edit]The serum-ascites albumin gradient can help determine the cause of the ascites.[7]

The color of the ascitic fluid can also be useful in analysis. Blood fluid can indicate trauma or malignancy. A milky appearance of the fluid can indicate lymphoma or malignant peritoneal ascites. Cloudy or turbid fluid can indicate possible infection or inflammation within the peritoneal cavity. Straw or light yellow colored fluid indicates more plasma-like and benign causes of peritoneal ascites.[3]

The ascitic white blood cell count can help determine if the ascites is infected. A count of 250 neutrophils per ml or higher is considered diagnostic for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Cultures of the fluid can be taken, but the yield is approximately 40% (72–90% if blood culture bottles are used). Empiric antibiotics are typically started when spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is highly suspected. A third-generation cephalosporin is typically started in these cases to cover the most common organisms, E. coli and Klebsiella, in SBP.[7]

Contraindications

[edit]Mild hematologic abnormalities do not increase the risk of bleeding.[12][7] The risk of bleeding may be increased if:[13]

- prothrombin time > 21 seconds

- international normalized ratio > 1.6

- platelet count < 50,000 per cubic millimeter.

Absolute contraindication is the acute abdomen that requires surgery.

Relative contraindications are:[6]

- Pregnancy

- Distended urinary bladder

- Abdominal wall cellulitis

- Distended bowel

- Intra-abdominal adhesions.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Paracentesis at eMedicine

- ^ Farlex dictionary > paracentesis, citing:

- Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Copyright 2008

- The American Heritage Medical Dictionary Copyright 2007

- McGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine. Copyright 2002

- ^ a b Tarn, A C; Lapworth, R (September 2010). "Biochemical analysis of ascitic (peritoneal) fluid: what should we measure?". Annals of Clinical Biochemistry: International Journal of Laboratory Medicine. 47 (5): 397–407. doi:10.1258/acb.2010.010048. PMID 20595402. S2CID 5578130.

- ^ a b "Ascites". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Millington, Scott J.; Koenig, Seth (1 July 2018). "Better With Ultrasound: Paracentesis". Chest. 154 (1): 177–184. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2018.03.034. PMID 29630894. S2CID 4735632.

- ^ a b c d e Aponte, E; Katta, S; O'Rourke, M.C. (9 September 2020). "Paracentesis". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. PMID 28613769. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Moore, K P; Aithal, G. P. (2006). "Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis". Gut. 55 (Suppl 6): vi1–12. doi:10.1136/gut.2006.099580. PMC 1860002. PMID 16966752.

- ^ a b Bernardi, Mauro; Caraceni, Paolo; Navickis, Roberta J. (28 December 2016). "Does the evidence support a survival benefit of albumin infusion in patients with cirrhosis undergoing large-volume paracentesis?". Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 11 (3): 191–192. doi:10.1080/17474124.2017.1275961. PMID 28004601.

- ^ "Treatments and Services | Gastroenterology and Hepatology | Dartmouth-Hitchcock". Archived from the original on 2012-04-23. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ^ "Paracentesis". Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2011-12-05.[full citation needed]

- ^ Sharzehi, Kaveh; Jain, Vishal; Naveed, Ammara; Schreibman, Ian (2014). "Hemorrhagic Complications of Paracentesis: A Systematic Review of the Literature". Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2014 985141. doi:10.1155/2014/985141. PMC 4280650. PMID 25580114.

- ^ McVay, PA; Toy, PT (1991). "Lack of increased bleeding after paracentesis and thoracentesis in patients with mild coagulation abnormalities". Transfusion. 31 (2): 164–71. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.1991.31291142949.x. PMID 1996485. S2CID 12286809.

- ^ Ginès, Pere; Cárdenas, Andrés; Arroyo, Vicente; Rodés, Juan (2004). "Management of Cirrhosis and Ascites". New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (16): 1646–54. doi:10.1056/NEJMra035021. PMID 15084697. S2CID 13452171.

External links

[edit]- WebMD: Patient guide