Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

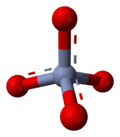

Chromate and dichromate

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic IUPAC name

Chromate and dichromate | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

| ||

| ChEBI |

| ||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank |

| ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII |

| ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

| ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| CrO2−4 and Cr2O2−7 | |||

| Molar mass | 115.994 g mol−1 and 215.988 g mol−1 | ||

| Conjugate acid | Chromic acid | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Chromate salts contain the chromate anion, CrO2−4. Dichromate salts contain the dichromate anion, Cr2O2−7. They are oxyanions of chromium in the +6 oxidation state and are moderately strong oxidizing agents. In an aqueous solution, chromate and dichromate ions can be interconvertible.

Chemical properties

[edit]Chromates react with hydrogen peroxide, giving products in which peroxide, O2−2, replaces one or more oxygen atoms. In acid solution the unstable blue peroxo complex Chromium(VI) oxide peroxide, CrO(O2)2, is formed; it is an uncharged covalent molecule, which may be extracted into ether. Addition of pyridine results in the formation of the more stable complex CrO(O2)2(pyridine).[1]

Acid–base properties

[edit]In aqueous solution, chromate and dichromate anions exist in a chemical equilibrium.

- 2 CrO2−4 + 2 H+ ⇌ Cr2O2−7 + H2O

The predominance diagram shows that the position of the equilibrium depends on both pH and the analytical concentration of chromium.[notes 1]

The chromate ion is the predominant species in alkaline solutions, but dichromate can become the predominant ion in acidic solutions.

Further condensation reactions can occur in strongly acidic solution with the formation of trichromates, Cr3O2−10, and tetrachromates, Cr4O2−13.[2] All polyoxyanions of chromium(VI) have structures made up of tetrahedral CrO4 units sharing corners.[3]

The hydrogen chromate ion, HCrO−4, is a weak acid:

- HCrO−4 ⇌ CrO2−4 + H+; pKa ≈ 5.9

It is also in equilibrium with the dichromate ion:

- 2 HCrO−4 ⇌ Cr2O2−7 + H2O

This equilibrium does not involve a change in hydrogen ion concentration, which would predict that the equilibrium is independent of pH. The red line on the predominance diagram is not quite horizontal due to the simultaneous equilibrium with the chromate ion. The hydrogen chromate ion may be protonated, with the formation of molecular chromic acid, H2CrO4, but the pKa for the equilibrium

- H2CrO4 ⇌ HCrO−4 + H+

is not well characterized. Reported values vary between about −0.8 and 1.6.[4]

The dichromate ion is a somewhat weaker base than the chromate ion:[5]

- HCr2O−7 ⇌ Cr2O2−7 + H+, pKa = 1.18

The pKa value for this reaction shows that it can be ignored at pH > 4.

Oxidation–reduction properties

[edit]The chromate and dichromate ions are fairly strong oxidizing agents. Commonly three electrons are added to a chromium atom, reducing it to oxidation state +3. In acid solution the aquated Cr3+ ion is produced.

- Cr2O2−7 + 14 H+ + 6 e− → 2 Cr3+ + 7 H2O ε0 = 1.33 V

In alkaline solution chromium(III) hydroxide is produced. The redox potential shows that chromates are weaker oxidizing agent in alkaline solution than in acid solution.[6]

- CrO2−4 + 4 H2O + 3 e− → Cr(OH)3 + 5 OH− ε0 = −0.13 V

Applications

[edit]

Approximately 136,000 tonnes (150,000 tons) of hexavalent chromium, mainly sodium dichromate, were produced in 1985.[8] Chromates and dichromates are used in chrome plating to protect metals from corrosion and to improve paint adhesion. Chromate and dichromate salts of heavy metals, lanthanides and alkaline earth metals are only very slightly soluble in water and are thus used as pigments. The lead-containing pigment chrome yellow was used for a very long time before environmental regulations discouraged its use.[7] When used as oxidizing agents or titrants in a redox chemical reaction, chromates and dichromates convert into trivalent chromium, Cr3+, salts of which typically have a distinctively different blue-green color.[8]

Natural occurrence and production

[edit]

The primary chromium ore is the mixed metal oxide chromite, FeCr2O4, found as brittle metallic black crystals or granules. Chromite ore is heated with a mixture of calcium carbonate and sodium carbonate in the presence of air. The chromium is oxidized to the hexavalent form, while the iron forms iron(III) oxide, Fe2O3:

- 4 FeCr2O4 + 8 Na2CO3 + 7 O2 → 8 Na2CrO4 + 2 Fe2O3 + 8 CO2

Subsequent leaching of this material at higher temperatures dissolves the chromates, leaving a residue of insoluble iron oxide. Normally the chromate solution is further processed to make chromium metal, but a chromate salt may be obtained directly from the liquor.[9]

Chromate containing minerals are rare. Crocoite, PbCrO4, which can occur as spectacular long red crystals, is the most commonly found chromate mineral. Rare potassium chromate minerals and related compounds are found in the Atacama Desert. Among them is lópezite – the only known dichromate mineral.[10]

As chromate is isostructural to sulfate, sulfate and chromate minerals can form solid solutions such as hashemite, and chromate minerals are often listed alongside sulfate minerals in mineral classification schemes such as Nickel-Strunz classification.

Toxicity

[edit]Hexavalent chromium compounds can be toxic and carcinogenic (IARC Group 1). Inhaling particles of hexavalent chromium compounds can cause lung cancer. Also positive associations have been observed between exposure to chromium (VI) compounds and cancer of the nose and nasal sinuses.[11] The use of chromate compounds in manufactured goods is restricted in the EU (and by market commonality the rest of the world) by EU Parliament directive on the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) Directive (2002/95/EC).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ pCr is equal to the negative of the decimal logarithm of the molar concentration of chromium. Thus, when pCr = 2, the chromium concentration is 10−2 mol/L.

References

[edit]- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 637. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Nazarchuk, Evgeny V.; Siidra, Oleg I.; Charkin, Dmitry O.; Kalmykov, Stepan N.; Kotova, Elena L. (2021-02-01). "Effect of solution acidity on the crystallization of polychromates in uranyl-bearing systems: synthesis and crystal structures of Rb2[(UO2)(Cr2O7)(NO3)2] and two new polymorphs of Rb2Cr3O10". Zeitschrift für Kristallographie - Crystalline Materials. 236 (1–2): 11–21. doi:10.1515/zkri-2020-0078. ISSN 2196-7105. S2CID 231808339.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 1009. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ IUPAC SC-Database. A comprehensive database of published data on equilibrium constants of metal complexes and ligands.

- ^ Brito, F.; Ascanioa, J.; Mateoa, S.; Hernándeza, C.; Araujoa, L.; Gili, P.; Martín-Zarzab, P.; Domínguez, S.; Mederos, A. (1997). "Equilibria of chromate(VI) species in acid medium and ab initio studies of these species". Polyhedron. 16 (21): 3835–3846. doi:10.1016/S0277-5387(97)00128-9.

- ^ Holleman, Arnold Frederik; Wiberg, Egon (2001), Wiberg, Nils (ed.), Inorganic Chemistry, translated by Eagleson, Mary; Brewer, William, San Diego/Berlin: Academic Press/De Gruyter, ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ^ a b Worobec, Mary Devine; Hogue, Cheryl (1992). Toxic Substances Controls Guide: Federal Regulation of Chemicals in the Environment. BNA Books. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-87179-752-0.

- ^ a b Anger, Gerd; Halstenberg, Jost; Hochgeschwender, Klaus; Scherhag, Christoph; Korallus, Ulrich; Knopf, Herbert; Schmidt, Peter; Ohlinger, Manfred (2005). "Chromium Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a07_067. ISBN 3527306730.

- ^ Papp, John F.; Lipin Bruce R. (2006). "Chromite". Industrial Minerals & Rocks: Commodities, Markets, and Uses (7th ed.). SME. ISBN 978-0-87335-233-8.

- ^ "Mines, Minerals and More". www.mindat.org.[page needed]

- ^ IARC (2012) [17–24 March 2009]. Volume 100C: Arsenic, Metals, Fibres, and Dusts (PDF). Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer. ISBN 978-92-832-0135-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-03-17. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

There is sufficient evidence in humans for the carcinogenicity of chromium (VI) compounds. Chromium (VI) compounds cause cancer of the lung. Also positive associations have been observed between exposure to chromium (VI) compounds and cancer of the nose and nasal sinuses. There is sufficient evidence in experimental animals for the carcinogenicity of chromium (VI) compounds. Chromium (VI) compounds are carcinogenic to humans (Group 1).

External links

[edit]Chromate and dichromate

View on GrokipediaChromate and dichromate are the CrO₄²⁻ and Cr₂O₇²⁻ anions, respectively, which constitute the key polyatomic ions in salts of hexavalent chromium. The chromate ion features a tetrahedral arrangement of four oxygen atoms around the central chromium atom, whereas the dichromate ion comprises two edge-sharing CrO₄ tetrahedra linked via a bridging oxygen.[1][2] These ions exhibit an acid-base equilibrium governed by the reaction 2 CrO₄²⁻ + 2 H⁺ ⇌ Cr₂O₇²⁻ + H₂O, wherein dichromate predominates in acidic media (appearing orange) and chromate in alkaline conditions (yellow).[3] Both serve as potent oxidizing agents due to the high oxidation state of chromium, finding applications in chrome plating for corrosion resistance, leather tanning, pigment formulation, and analytical chemistry as titrants.[4] However, hexavalent chromium compounds like these are highly toxic, acting as carcinogens through mechanisms involving cellular uptake and DNA damage, prompting regulatory restrictions on their industrial deployment.[5][6]