Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

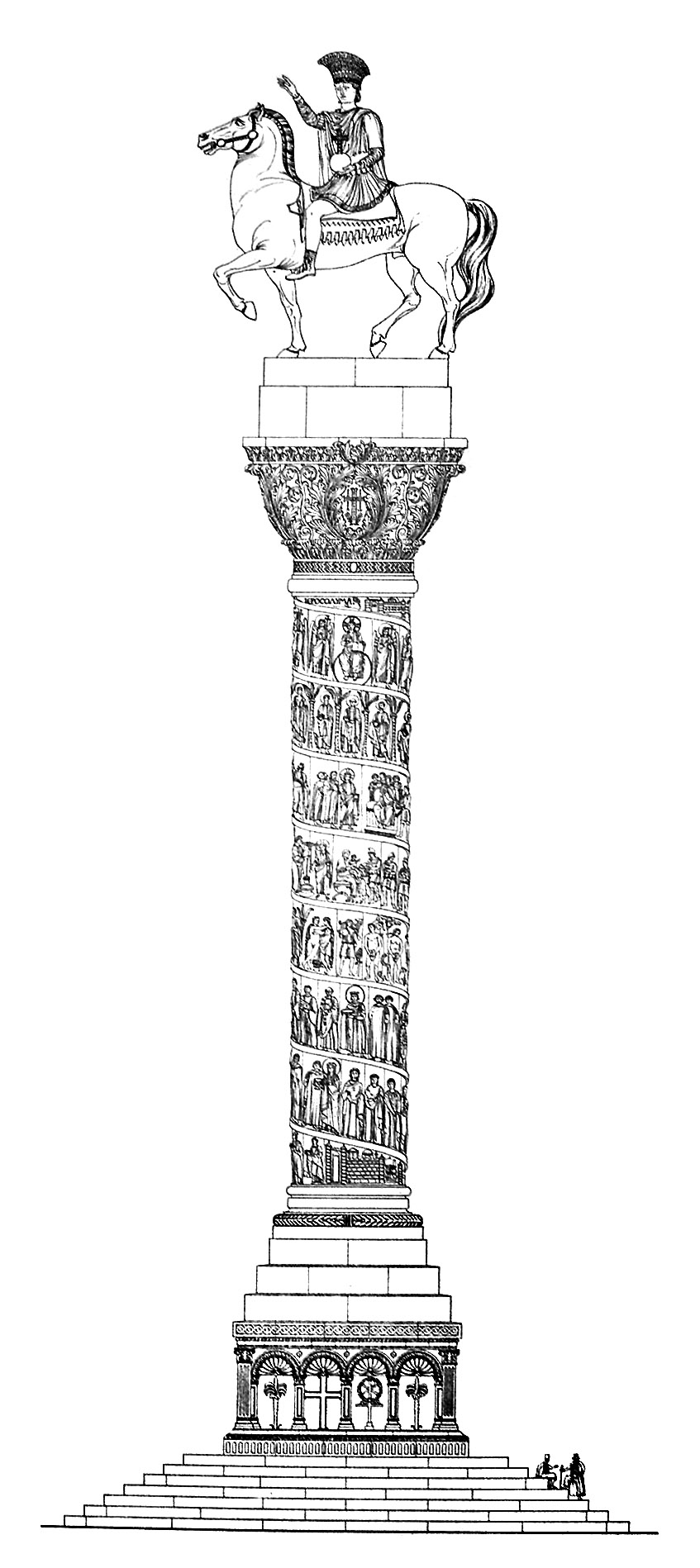

Column of Justinian

View on Wikipedia

The Column of Justinian was a Roman triumphal column erected in Constantinople by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I in honour of his victories in 543.[1] It stood in the western side of the great square of the Augustaeum, between the Hagia Sophia and the Great Palace, and survived until 1509, its demolition by the Great earthquake of Constantinople[2] which affected other historical places as well.

Description and history

[edit]The column was made of brick, and covered with brass plaques.[3] The column stood on a marble pedestal of seven steps, and was topped by a colossal bronze equestrian statue of the emperor in triumphal attire (the "dress of Achilles" as Procopius calls it), wearing an antique-style muscle cuirass, a plumed helmet of peacock feathers (the toupha), holding a globus cruciger on his left hand and stretching his right hand to the East.[4] There is some evidence from the inscriptions on the statue that it may actually have been a reused earlier statue of Theodosius I or Theodosius II.[3][5]

The column survived intact until late Byzantine times, when it was described by Nicephorus Gregoras,[6] as well as by several Russian pilgrims to the city. The latter also mentioned the existence, before the column, of a group of three bronze statues of "pagan (or Saracen) emperors", placed on shorter columns or pedestals, who kneeled in submission before it. These apparently survived until the late 1420s, but were removed sometime before 1433.[7] The column itself is described as being of great height, 70 meters according to Cristoforo Buondelmonti. It was visible from the sea, and once, according to Gregoras, when the toupha fell off, its restoration required the services of an acrobat, who used a rope slung from the roof of the Hagia Sophia.[8][9]

By the 15th century, the statue, by virtue of its prominent position, was actually believed to be that of the city's founder, Constantine the Great.[5] Other associations were also current: the Italian antiquarian Cyriacus of Ancona was told that it represented Heraclius.[5] It was therefore widely held that the column, and in particular the large globus cruciger, or "apple", as it was popularly known, represented the city's genius loci.[10] Consequently, its fall from the statue's hand, sometime between 1422 and 1427, was seen as a sign of the city's impending doom.[11] Pierre Gilles, a French scholar living in the city in the 1540s, gave an account of the statue's remaining fragments, which lay in the Topkapi Palace, before being melted to make cannons:[10]

Among the fragments were the leg of Justinian, which exceeded my height, and his nose, which was over nine inches long. I dared not measure the horse's legs [...] but privately measured one of the hoofs and found it to be nine inches in height.

The appearance of the statue itself with its inscriptions is preserved, however, in a 1430s drawing made by Giovanni Dario at the behest of Cyriacus of Ancona.

References

[edit]- ^ Brian Croke, "Justinian's Constantinople", in: Michael Maas (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian (Cambridge 2005), pp. 60-86 (p. 66).

- ^ Semavi EYİCE. Yabancıların Gözünden Bizans İstanbul'u

- ^ a b Kazhdan (1991), p. 232

- ^ Procopius, De Aedificiis, I.2.1–11

- ^ a b c Majeska (1984), p. 239

- ^ Nicephorus Gregoras, Roman History, I.7.12.

- ^ Majeska (1984), pp. 237, 240

- ^ Majeska (1984), p. 238

- ^ Kazhdan (1991), p. 2100

- ^ a b Finkel (2006), p. 53

- ^ Majeska (1984), p. 240

Sources

[edit]- Finkel, Caroline (2006). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire 1300–1923. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6112-2.

- Guilland, Rodolphe (1969), Études de topographie de Constantinople byzantine, Tomes I & II (in French), Berlin: Akademie-Verlag

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- Majeska, George P. (1984). Russian Travelers to Constantinople in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-101-8.

- Raby, J. (1987). "Mehmed the Conqueror and the Equestrian Statue of the Augustaion" (PDF). Illinois Classical Studies. 12 (2): 305–313. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2010-08-17.

External links

[edit]- 3D reconstruction at the Byzantium 1200 project

- Four fifteenth-century travellers look at the Statue of Justinian